Clinical Biochemistry

1/280

Earn XP

Description and Tags

1hr exam SAQ 7-8 (75%), ERQ 2 (25%)

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

281 Terms

Clinical chemistry definition

The biochemical analysis of body fluids to support the diagnosis and treatment of disease

Utilizes chemical reactions to identify or quantify levels of chemical compounds in bodily fluids

Instrumentation (Techniques) (20)

Autoanalysers

Calibration curves

Enzymes

Spectrophotometry and photometry

Spectrofluorimetry

Atomic absorption and emission spectrophotometry

Electrochemistry and ion-selective electrodes

Electrophoresis and related techniques

Chromatography and mass spectrometry

Immunoassays

Renal function tests

Electrolyte balance and blood gases

Liver function, enzymes, and isoenzymes

Carbohydrate metabolism

Lipid and lipoprotein metabolism

Hypothalamus and pituitary axis

Thyroid function

Sex hormones

Adrenal hormones

Tumour markers

Biochemical Analysis

Characterisation of biological components in a sample using laboratory techniques

Samples:

Blood

Serum

Plasma

Urine

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

Synovial fluid

Saliva

Other body fluids or tissues depending on the test

Qualitative vs Quantitative analysis of BA

Qualitative analysis:

Determines whether a biomolecule is present or absent

Offers a binary outcome (positive or negative)

Example: Testing blood for a particular drug or presence of a biomarker

Quantitative analysis:

Determines the quantity or concentration of a biological molecule in a sample

Measures amount or concentration

Example: pH, haemoglobin, or glucose concentration in blood

Criteria for Selecting an Analytical Method (11)

Number of samples to be analysed

Cost of test and availability of equipment

Ease and convenience of the method

Duration of analysis (turnaround time)

Required level of accuracy and precision

Expected concentration range of the analyte

Sensitivity and detection limit of the technique

Analytical specificity

Type and physical form of the sample

Likelihood of interfering substances (e.g. lipaemia, cross-reactivity)

Operator skills and expertise (=training)

Lipaemia

The presence of a high concentration of lipids (mainly triglycerides) in the blood

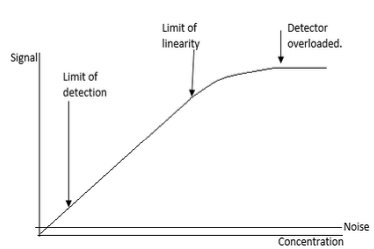

Linearity

Ability of a test to provide results directly proportional to analyte concentration in a sample

Limits of Linearity

Defines a limited range of values between which results are regarded as accurate

If results exceed the upper limit: dilute sample and retest to obtain accurate value

If results are below the accepted value: repeat test, report result, inform physician, occasionally repeat using larger sample volumes, or analyse other analytes

Results outside the linear range require specific corrective actions

Limit of Detection (LOD)

Limit of Detection (LOD)

Lowest analyte concentration that can be distinguished with reasonable confidence from blank or background

Important for comparing analytical procedures, techniques, or instruments

Analytical Specificity

Ability to measure only the analyte of interest

Example: Immunoassays rely on Ag-Ab interactions

Ideally fully specific, but cross-reactivity or interfering substances can occur → obtain detailed patient history to report results confidently

Analytical Sensitivity

Smallest amount or concentration of an analyte that can be detected

Related to limit of detection (LOD) for the assay

Depends on assay generation (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.)

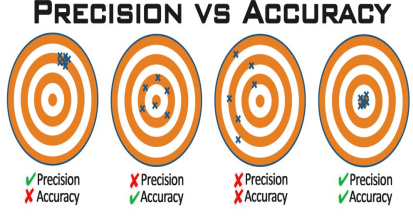

Accuracy vs. Precision

Accuracy:

Ability of a test to produce the true value of an analyte in a sample

Multiple measurements of the same analyte will distribute around the true value

The mean of measurements represents the true value

Check: Compare with different methods

Poor accuracy → procedural or equipment flaws

Precision:

Ability of a test to reproduce the same result consistently in the same specimen

Spread or distribution of results reflects method variability

Variability expressed as Standard Deviation (SD)

Reproducibility: Check by repeating measurements (trials)

Poor precision → poor technique

Accuracy and Precision

Accurate but Imprecise: Close to true value on average but results are scattered → Random Error

Precise but not Accurate: Results are consistent but deviate from true value → Systematic Error

Inaccurate & Imprecise: Scattered and far from true value → poor measurement

Accurate & Precise: Ideal state, results are consistent and close to true value (difficult to achieve due to multiple variables like lab staff, steps involved)

Improving Accuracy

Using properly standardized procedures

Statistically valid comparisons of new methods with established reference methods

Using samples of known values (controls)

Participation in proficiency testing (PT) programs

Ensuring Precision

Proper inclusion of standards

Using reference samples or control solutions

Statistically valid replicate determinations of a single sample

Duplicate determinations of sufficient numbers of unknown samples

Measuring day-to-day and between-run precision using control samples

Accuracy and Precision photo

Faulty weighing balance

May give precise (repeatable) but inaccurate (untrue) results

What can be done:

Perform precision checks (repeat measurements)

Compare with known standards or reference methods to detect bias

Calibrate the instrument regularly to correct systematic errors

Random Error

Test values scattered around true mean

Imprecise, usually >2 SD apart

Systematic Error /Bias

Constant bias from true value

Results are grouped closely (within 1 SD) but different from true mean

Measurement error that skews results consistently to one side

Causes:

Incorrectly calibrated instruments

Change in reagent/calibrator lot

Inadequate storage of reagents/calibrators

Pipettor misadjustments or misalignments causing volume changes

Temperature changes in incubators or reaction blocks

Procedural differences between operators

To Overcome:

Use carefully standardised procedures

Measure a single variable in several different ways and compare results

Work blind when possible (e.g., use of codes)

Measurement Error

Examples:

Mistakes in taking readings

Faulty equipment

Equipment accuracy limits

Errors in preparing solutions or dilutions

Calibration errors

Interfering substances

To Overcome:

Take repeated readings

Compare readings between instruments

Spike and measure recovery: add a known amount of analyte to the sample and compare the response to the same spike in standard diluent

Keep records of batch numbers and measurements for solutions

Check controls or standards and construct standard/calibration curves

Validation Procedures

Use Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

Calibrate assays with certified reference materials containing known analyte amounts, traceable to a national reference lab

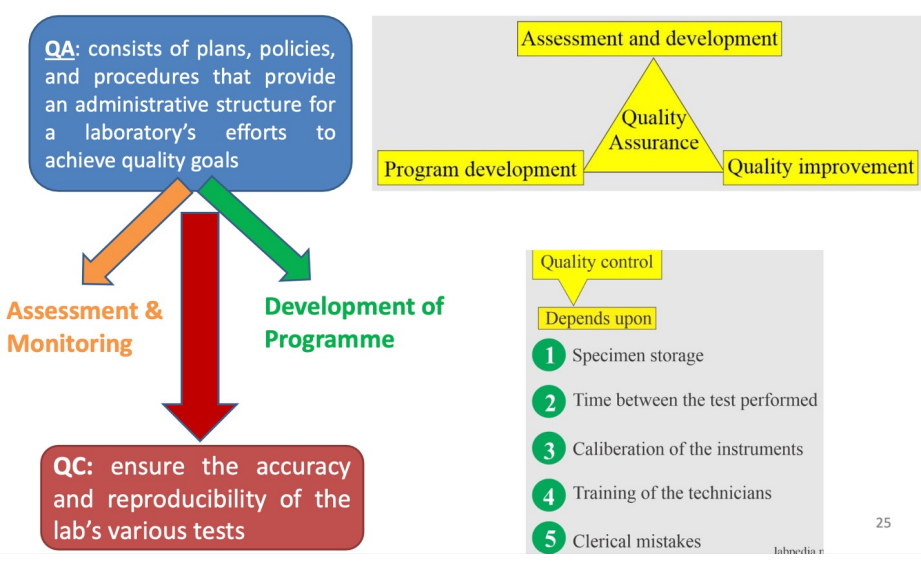

Quality Assurance (QA): System to verify the entire analytical process operates within acceptable limits

Quality Control (QC): Mechanisms to measure non-conforming method performance

Importance:

Essential for all assays

Provides confidence in precision and accuracy of tests

Enables early detection of poor assay performance

Allows proper corrective actions to minimize the risk of patients receiving incorrect result

Keep Records:

Batch numbers

Analysis performance

Results

Reagent and calibrator temperatures

Ability to quote assay performance at measurement time allows labs to defend results and gives clinicians confidence in patient care

SOP (Standard Operating Procedure)

A documented set of step-by-step instructions that describes how to perform a specific laboratory or clinical procedure consistently and correctly

Purpose:

Ensures consistency and reliability of results

Maintains quality and safety

Helps train staff and reduce errors

Provides a reference for audits and compliance

Calibration

Aligning an instrument to provide accurate, precise, and unbiased measurements consistent with other instruments at a precise point

Purpose:

Ensure accuracy and precision

Reduce/eliminate bias across a range of values

Maintain consistency between instruments

Important Notes:

Poor standard preparation → inaccurate results

Never extrapolate beyond the highest standard - assume linearity only within calibrated range

Be consistent in significant figures used

How Calibration is Done

Select reference standards with known values covering the range of interest

Measure standards using the instrument to be calibrated

Plot calibration curve/standard curve (response vs known values)

Use the curve to determine amount/concentration in test samples

Correct measurements using the inverse of the calibration curve if necessary

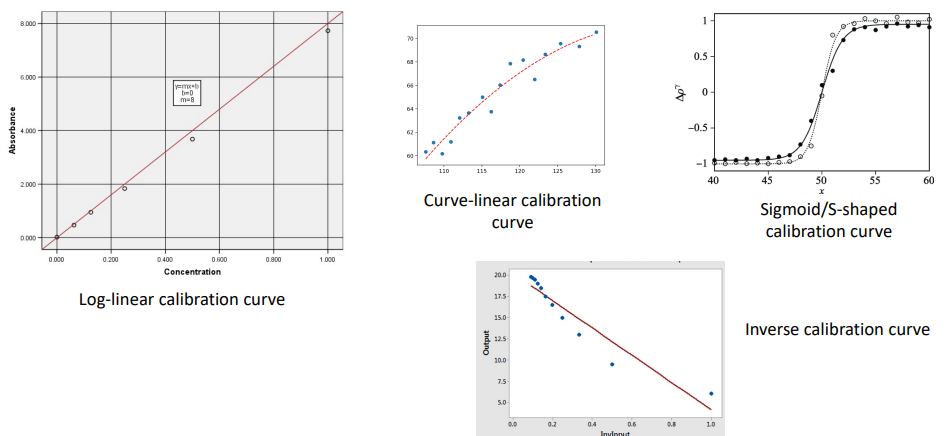

Types of Calibration Curve (photo)

Preparation of a Calibration Curve (9)

Choose an appropriate test method

Select amount/concentration, range, and number of standards covering expected sample levels

Prepare standards carefully (consider volumetric accuracy, standing time, temperature, light protection, include blank/zero standard)

Assay standards and test samples simultaneously; take replicate readings

For some instruments, periodically check zero and highest standard to ensure stability

Draw the standard curve or determine underlying relationship

Draw line of best fit for linear curves

Quote r² to indicate fit quality

Determine unknown sample concentrations from the curve or mathematical relationship (e.g., y=mx+c)

Correct for dilution/concentration if test samples were diluted

Example: 0.2 mL assayed → multiply result by 5 for value per 1 mL

Quote results to an appropriate number of significant figures, reflecting method accuracy and consistency

When to Carry Out Calibration? (8)

Before major or critical measurements

Before measurements requiring high accuracy

After major or critical measurements

When data are unreliable or observations appear questionable

After incidents that may affect the instrument (e.g., impact, accidents)

For long-term instrument use, as conditions can change over time

Per experiment requirements, e.g., when calibration certificates are needed or using a new kit

As indicated by the manufacturer, following periodic calibration schedules to ensure proper and safe instrument function

Preparing Serial Dilutions

Linear Dilution Series:

Concentrations separated by an equal amount (e.g., 0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 µg/mL)

Steps:

Prepare a stock solution

Use formula [C1]V1 = [C2]V2 to calculate volumes

Tools like the Tocris dilution calculator can help determine volumes for desired concentrations

V1 = volume of stock solution

V2 = volume of diluted solution

C1 = starting concentration

C2 = target diluted concentration

Logarithmic Serial Dilution:

Concentrations separated by a constant proportion rather than equal increments

Clinical Sensitivity

Describes the ability of an assay to detect only patients with a particular disease

Clinical Specificity

Describes the ability of an assay to detect individuals who do not t have a particular disease

Clinical Validation

Examines the probability that an analytically correct result is really possible for that patient

Auto-Validation of Results

Delta Check: examine any value obtained for an analyte against the previous result

Range Check: determines whether the result is physiologically possible

Reference Range: within which 95% of the healthy population fall

Automation

Steps which were previously performed manually can now be automated

Scientist can focus on tasks that are not automated

Increases efficiency and capacity

Automation has been extended into areas not related to analysis:

Processing and transportation of specimens

Loading of samples onto analysers

Assessing results of the performed tests

Clinical Laboratory Automation

Integration of robotic transport systems with analytical instruments and pre/post-analytical equipment (e.g., centrifuges, aliquoters, decappers, recappers, sorters, specimen storage/retrieval)

Computers controlling devices must be interfaced with each other and/or the LIS

Types of information communicated include:

Process control and status of devices/analyzers, specimens, containers, and carriers

Patient, order, and result data

Specimen flow algorithms and automated decision-making

Ensures each specimen/aliquot undergoes correct tests in the proper sequence

Why Do We Need Automation?

Increases the number of tests one person can perform in a given time

Minimises result variations between operators

Reduces errors from manual analyses (e.g., equipment variations, pipettes)

Uses less sample and reagent per test

Allows scientists to focus on decision-making and result interpretation

Expands lab services into specialised and technically demanding assays

Makes performing repeats easier when necessary

Provides walkaway operations and standardised methodology for accurate and reproducible results

Limitations of Automation

Some basic steps might not be fully automated:

Specimen preparation and identification

Labelling (critical)

Programming of instruments

Checking Quality Assurance (QA) and Quality Control (QC) – of utmost importance

Analytic Process & Automation

Can be divided into 3 major phases:

Pre-analytic: Sample processing

Steps before the actual chemical analysis

Includes:

Patient preparation

Specimen collection, handling, and transportation

Labelling and identification

Sample processing (e.g., centrifugation, aliquoting)

Critical because errors here can affect all downstream results

Analytic: Chemical analyses

Steps during the actual chemical analysis

Includes:

Measurement of analytes using chemical or instrumental techniques

Use of calibration, standards, and controls

Ensuring accuracy, precision, and quality control

Most automated phase

Post-analytic: Data management

Steps after the chemical analysis

Includes:

Data verification and validation

Interpretation of results

Reporting results to clinicians

Archiving and record-keeping

Increasingly targeted for automation to improve efficiency and reduce human error

Research is increasingly focused on automating pre-analytic and post-analytic processes

Auto-validation

Automated process of result validation based on criteria set by scientific and clinical staff

Post-analytical automation mainly involves it

Benefits:

Improves turnaround time by automatically validating results that meet preset criteria

Withholds results that need further attention (e.g., out-of-range, repeats)

Introduces a uniform standard of validation across the laboratory

Types of Analysers

Continuous Flow Analysers

Centrifugal Analysers

Discrete Analysers

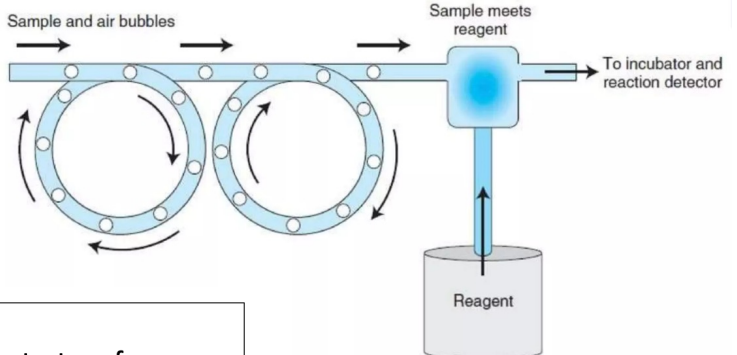

Continuous Flow Analysers

Liquids (reagents, diluents, samples) are pumped through continuous tubing

Samples introduced sequentially, following the same network and reaction path

Air bubbles at regular intervals separate and clean tubing

Sample + reagent → chemical reaction → chromagen solution pumped for spectrophotometric analysis

Advantages:

Uniformity in test performance

Run many samples requiring the same procedure

Multiple tests on each sample

Disadvantages:

Carry-over problems

Wasteful use of continuously flowing reagents

Continuous Flow Analysers (photo)

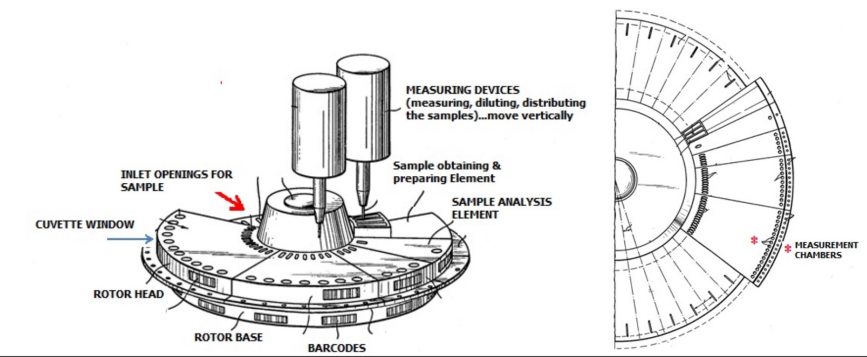

Centrifugal Analysers

Use centrifugal force to mix sample aliquot with reagent in spinning rotor

Sample + reagent passes through detector for quantification

Features:

Single-test batch analysers

Sequential analysis

Discrete (one compartment per assay)

Parallel analysis possible

Uses the force generated by centrifugation to transfer and then contain liquids in separate cuvettes for measurement at the perimeter of a spinning rotor

Advantage: Capable of batch analysis (multiple samples, one test at a time)

Centrifugal Analysers (photo)

Discrete Analysers

Most widely used automation type; most versatile

Each sample and reagent in separate cuvette/container

Can run:

Multiple tests on one sample (random access; e.g., LFTs, FBG)

Multiple samples, one test at a time (batch analysis; e.g., FBG on 20 patients)

Random Access:

Analysis kept separate in reaction chambers (cuvettes, wells, slides)

Minimizes carryover, but increases cost per test due to disposables

Batch Analysis:

Accumulating specimens into one run reduces reagent and personnel costs

Cost-effective for specialty tests with small order

Modern Discrete Analyser Capabilities

Routine and special chemistries, including enzymes, substrates, electrolytes, proteins, drugs of abuse, therapeutic drug monitoring

Capacity: up to 300 tests/hour

Continuous access to samples, reagents, cuvettes

On-board storage: 84 routine samples, 6 STAT samples, 39 fixed cooled calibrator/control positions, 45 refrigerated reagent positions, 600 cuvette storage positions

Low-volume cuvettes reduce reagent consumption and running costs

Automatic clot detection ensures result integrity

Integrated touchscreen workstation enables fast and convenient data management

Laboratory Information Systems (LIS)

Important development in laboratory automation

Initially used to generate consolidated laboratory result reports

Evolved to capture test requests and results and manage laboratory workflow

Has improved the overall quality of laboratory data

Types of Automation

Total Laboratory Automation (TLA):

First developed in the 1980s in Japan

Conveyor belts carry specimens to workstations

Automated pipettors aspirate serum from tubes for testing

Can include pre-analytical modules: centrifugation, decapping, aliquoting, labelling

Includes transport system for tube delivery to analysers, recapping, sorting, and storage of specimens

Modular Automation:

Integrates different aspects of automation and analysis into one module

Task-targeted automation systems for specific functions

Flexible: modules can be added or upgraded as lab needs change

Can operate independently or linked with other modules or LIS

Often includes sample handling, analysis, and reporting within a single module

Selecting the Analyser

Things to Consider:

Laboratory’s Workload:

Discrete vs large batch testing

open vs closed system

Single instrument or multiple instruments – ease of use & complexity

Back-up options vs outsourcing

Storage of Reagents:

Need for refrigeration or freezing

Effect of repeat freeze-thaw cycles

Random access

Patient/test orientation

STAT (emergency) facilities

Temperature control system (water bath vs Peltier effect)

Maintenance requirements

Running costs (excluding reagents, plastic ware, etc.)

Quality Assurance (PHOTO!)

Quality Control (QC)

Purpose:

Ensure accuracy and reproducibility of laboratory tests

Provide early warning of errors so corrective action can prevent major mistakes

Maintain continuous record of test precision

Monitor analytic process and evaluate method accuracy

Evaluate technologist skills

Determine analytical errors during analysis

Prevent incorrect patient values

QC Goals:

Accuracy

Precision

Total error of the chemical method

Ideal Properties of QC Materials:

Resemble human serum, plasma, blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid

Stable for prolonged periods without interfering preservatives

Free from communicable diseases (bacteria, viruses, fungi)

Known concentration of analytes

Easy to store and dispense

Affordable

QC Objectives:

Continuous accuracy of results

Early warning to take remedies before major mistakes

Compare tests at different times using the same control sera

QC Tools:

Procedure manuals

Maintenance schedules

Calibrations

Quality assurance programs

Staff training

QC Results:

Acceptable: Within error limits

Unacceptable: Excessive errors, out of range

Types of QC Reagents

Pooled Sera:

Analyte levels usually within normal patient range; not suitable for clinically significant levels

Stability not validated like true third-party control

Increased infection risk (may not be tested for HIV, Hepatitis)

Inconsistent long-term supply

Company/Third-Party Produced Controls:

Extended shelf life and stability

Enable long-term QC monitoring

Detect shifts when reagents or calibrator lots change

Quality Assurance (QA) vs Quality Control (QC)

Aspect | Quality Assurance (QA) | Quality Control (QC) |

|---|---|---|

Definition | Set of activities to ensure quality in processes by which products/tests are developed | Product-oriented activities to ensure quality in finished products/tests |

Focus | Prevent defects by improving processes | Identify and correct defects in products/tests |

Goal | Ensure defects do not arise | Detect defects before release |

How | Establish, implement, and audit quality management systems | Use tools, equipment, assays, and procedures to find defects |

Orientation | Proactive; preventive | Reactive; corrective |

Process vs Product | Process | Product |

Sampling vs Specifications | Specifications | Sampling |

Assays vs Documentation | Documentation | Assays |

Organisation vs Authorisation | Organisation | Authorisation |

Function Type | Staff function | Line function |

Defect Handling | Prevent defects | Find and correct defects |

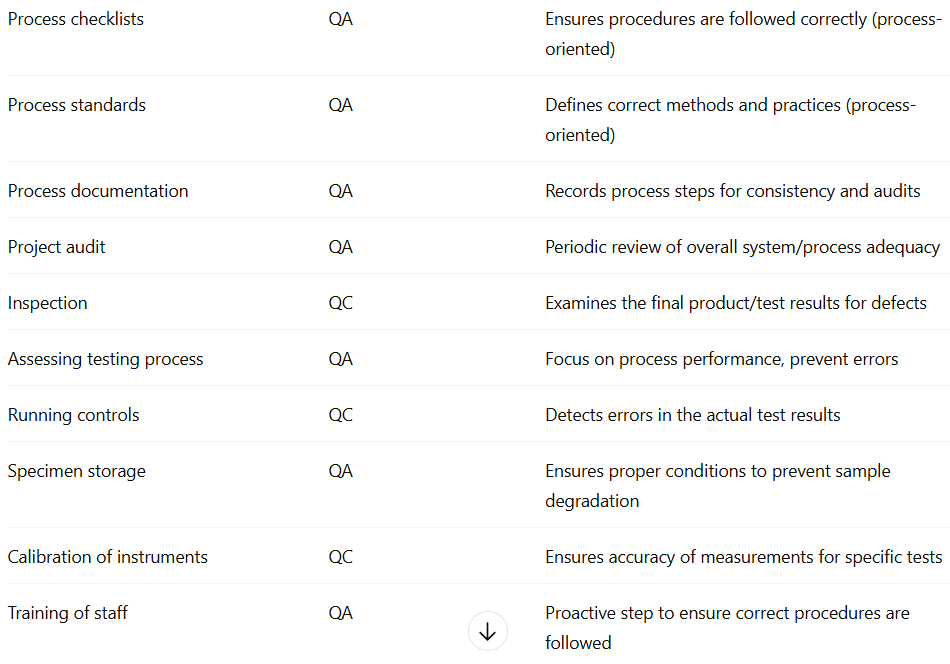

Examples of QC vs QA (photo)

Pre-Analytical Errors Prevention

Patient identification & labelling: Use barcode technology to reduce errors

Record keeping: Track sample receipt and reporting

Request form checks: Confirm test tube, name, and requested tests

Sample adequacy: Ensure sufficient volume

Sample quality: Check for haemolysis, lipemia, icterus

Patient history: Record food intake, alcohol, drugs, smoking, stress, sleep, posture; explain instructions for sample collection

Containers & preservatives: Use correct types to avoid affecting results

Transport: Ensure proper handling to protect sample integrity

Processing: Correct separation (e.g., centrifugation) with proper speed, temperature, and operator technique

Analytical Errors Prevention

Preventive maintenance: Daily/monthly schedules for instruments

Equipment checks: Monitor water quality, power supply, calibrate balances, glassware, pipettes

Reagents/kits: Date upon receipt and opening

Lot validation: Run new reagent lots in parallel with old ones before use

Standards:

Primary standard: Highly purified substance

Secondary standard: Concentration determined by comparison with primary standard

Post-analytic errors: Avoid errors in recording and reporting results

Quality Management (photo)

Photometry

The measurement of luminous light (luminous intensity) falling on a surface from a light source

Photometric instruments measure light intensity without considering wavelength (λ)

Electromagnetic Radiation

Described as photons of energy traveling in waves

Frequency is inversely proportional to wavelength (λ)

Energy is inversely proportional to wavelength (shorter wavelength = higher energy)

Spectrum ranges from short-wavelength, high-energy gamma and X-rays to long-wavelength radio waves

Absorption and Emission

Spectrophotometers and photometers measure absorption or emission of radiant energy to determine concentration

Absorption or emission of energy by atoms produces a line spectrum

Molecules absorb or emit energy over a broad region (band spectrum)

Solids produce a continuous spectrum

Absorbance: amount of light absorbed

Excited electrons return to ground state by emitting a specific wavelength of radiant energy

Light Interaction with Solution

When a light beam enters a solution:

Some light is absorbed

The remaining transmitted light reaches the detector and is converted into an electrical signal

The amount of light absorbed varies according to the concentration of the substance

Light Interaction with Solution (photo)

% Transmittance (T)

Defined as the ratio of radiant energy transmitted (It) to radiant energy incident on the sample (I₀):

T = It / I₀If all light is absorbed or blocked → 0% T (e.g. a very concentrated sample)

It is important to always run a blank to account for background absorbance

Absorbance (A) = –log(T) = –log(It / I₀)

The difference in transmitted light between the blank and the sample is due only to the compound being measured

Beer’s Law (Beer-Lambert Law)

Establishes the relationship between analyte concentration and absorbance

States that absorbance (A) is directly proportional to concentration (c) and path length (L)

Mathematically:

A = ε × L × cε = molar absorptivity (ability of a molecule to absorb a specific wavelength)

L = path length of light through the solution

c = concentration of the absorbing molecule

The amount of light absorbed at a given wavelength depends on:

Type of molecules or ions present

Concentration

pH and temperature

Absorbance and Concentration

Unknown concentrations are determined using a calibration curve plotting absorbance vs. concentration for known standards

This allows for accurate quantitative analysis and instrument calibration

Spectrophotometry

When light passes through an object, part of it is reflected, absorbed, and transmitted

Purpose: Measures the amount of light transmitted by a solution to determine the concentration of the light-absorbing substance

Principle: Measures light intensity as a function of wavelength by:

Diffracting the light beam into a spectrum of wavelengths

Directing it onto a sample

Receiving and detecting the transmitted or reflected light

Measuring the intensity and displaying it as a graph on the detector/display device

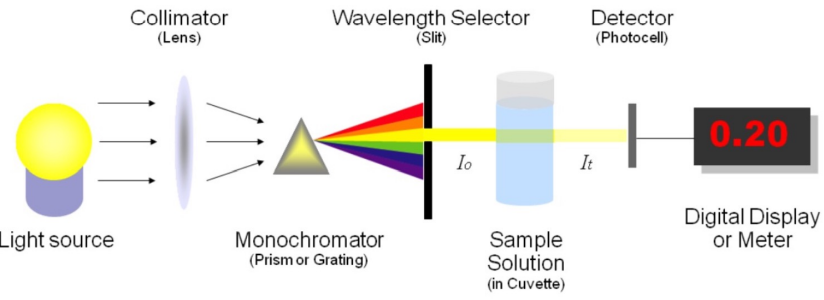

Spectrophotometer Components

Light Source

Monochromator

Sample Cell (Cuvette)

Photodetector

Light Source

Provides the initial beam of radiant energy

Important factors:

Range/Bandwidth (spectral distribution)

Brightness

Stability (bulb condition)

Temperature

Lifetime

Common Light Sources

Source

Region

Notes

Tungsten Lamp

Visible & IR

- Produces 320–2500 nm range- Often paired with heat-absorbing filter to block IR- Glass construction (400–800 nm)

Advantages: Cheap, non-toxic, good for small-area lighting

Disadvantages: Inefficient (90% energy lost as heat), unsuitable for large areas

Deuterium Lamp

UV

- Continuous emission down to 165 nm- Common for UV work (160–325 nm)- Quartz construction (does not block UV)

Mercury or Xenon Lamp

UV-Vis

- Mercury provides line spectra; Xenon provides continuous spectra

Laser

Variable - Xray/ UV/ IR

- High power, narrow bandwidth, coherent, tunable wavelength, very expensive

Plasma/Furnace Sources

Elemental studies

Used for atomic absorption or emission spectroscopy

Monochromator

Purpose: To isolate individual wavelengths of light and direct only one onto the sample

Reason: Each compound absorbs optimally at a specific wavelength (e.g. Urea: 260–280 nm; Creatinine: 280–320 nm)

Function:

Isolation of wavelength depends on the entrance and exit slit width

Bandpass (bandwidth): Defines the range of wavelengths transmitted

Slit width determines resolution and signal-to-noise ratio

Large slit width: More light energy → higher signal-to-noise ratio → lower resolution

Small slit width: Less energy → lower signal-to-noise ratio → better resolution

Wide slit → more energy, lower resolution

Narrow slit → less energy, higher resolution

Diffraction gratings = most accurate and commonly used

Coloured-glass filters = cheapest, least precise

Interference filters = narrow, efficient, precise

Prism = adjustable, produces continuous spectrum

Types of Monochromators

Coloured-Glass Filters

Interference Filters

Prism

Diffraction Gratings

Coloured-Glass Filters - Monochromators

Simple filters that transmit a wide band of wavelengths and absorb others

Features:

Least expensive and simple to use

Pass a broad range of wavelengths with low precision

Application: Used in colorimeters for measuring color intensity

Interference Filters - Monochromators

Based on constructive interference of light waves

Construction: Two glass plates, each mirrored on one side, separated by a transparent spacer equal to half the target wavelength

Features:

Produces monochromatic light with a narrow bandwidth

Provides high efficiency and better wavelength selectivity

Prism - Monochromators

Light is refracted as it enters and exits the prism, separating white light into its spectral components

Operation:

A narrow light beam enters the prism and disperses into a continuous spectrum

Rotation of the prism allows selection of the desired wavelength through the exit slit

Output: Continuous spectrum with adjustable wavelength selection

Diffraction Gratings - Monochromators

Most commonly used monochromator type

Construction: A polished surface etched with many fine parallel grooves (15,000–30,000 per inch)

Principle:

Light is diffracted (bent) when it passes by sharp edges

Constructive interference (in-phase waves) reinforces certain wavelengths → produces clear spectral lines

Destructive interference (out-of-phase waves) cancels out others

Output: Complete and highly resolved spectra

Note: Accessory filters are often added to reduce stray light caused by multiple diffraction orders

Sample Cell (Cuvette)

Shape: Can be round or square

Key Point: The light path must remain constant since absorbance is directly proportional to concentration

Round cuvettes:

Must have an etched mark indicating the correct position for use

Square cuvettes:

Have plane-parallel optical surfaces and a constant light path

Frosted sides to ensure correct positioning

Advantages:

Reduced lens effect and refraction errors

Less dependent on orientation

Most commonly used type

Condition:

Cuvettes with scratches scatter light and should be discarded

Material:

Glass cuvettes: Cheap and disposable; suitable for visible range but absorb UV light

Quartz cuvettes: Reusable and essential for UV applications

Photodetector

Purpose: Converts transmitted radiant energy into an equivalent electrical signal

Choice of detector: Depends on the wavelength being studied

Single-beam spectrophotometer: 100% transmittance control must be adjusted each time the wavelength is changed

Types of detectors:

Potentiometric recorders

Photocell

Phototube

Photomultiplier (PM) tube

Amplifiers & Ammeters

Requirements:

High sensitivity to detect low radiant energy

Short response time

Long-term stability

Electrical signal easily amplified for readout

Photomultiplier (PM) Tube - Photodetector

Purpose: Detects and amplifies radiant energy

Advantages:

200× more sensitive than other detectors

Ideal for extremely low light levels or very short light flashes

Current signal is proportional to light intensity

Analog signal is converted to voltage, then to digital via an A/D converter

Single-beam Spectrophotometer

One light path for both reference and sample

Light passes through collimating lens → entrance slit → filter → sample → shutter → photovoltaic cell → readout

Requires blank for correction between reference and sample absorbance

Advantages:

Less expensive

High energy throughput → high sensitivity

Easy to operate

Disadvantages:

Instability from electronic, voltage, or mechanical fluctuations

Must be zeroed or calibrated regularly → human error

Variations in light intensity → errors in %T

Non-monochromatic light → deviation from Beer’s law

%T and A not “true” values

Not designed for spectral data

Double-beam Spectrophotometer

Splits light path into reference and working segments

Automatically corrects for variations in light intensity

Advantages:

High speed, stability, flexibility

Reduces errors from single-beam fluctuations

More reproducible measurements

Typically simpler operation

Wavelengths easily selected

Disadvantages:

Changes in wavelength may cause variations

Measurement Options

Qualitative Analysis

Quantitative Analysis

Typical Plate-based Spectrophotometric Assay

Enzyme Assays

Qualitative Analysis

Visible and UV spectrophotometers can identify classes of compounds in pure or biological samples

Done by plotting absorption spectrum curves

Absorption in different regions gives structural hints

Absorption Range (nm)

Structure / Type of Compounds

220–280

Aliphatic or alicyclic hydrocarbons or derivatives

220–250

Compounds with two unsaturated linkages in conjugation, benzene derivatives

250–330

Compounds with more than two conjugated double bonds

450–500

Beta-carotene (11 conjugated double bonds, precursor of Vitamin A)

250–330

Vitamin K1

Quantitative Analysis

Substrates: UA, Urea, Creatinine, LFTs, Lipid profile, etc

DNA

Protein (measured at 280 nm, depends on tyrosine and tryptophan content)

Typical Plate-based Spectrophotometric Assay

Often kit-based, specific for particular analyte (e.g., ELISAs, small molecules, lipids)

Prepare standards of known concentrations

Add samples to wells

Add reactants (assay-dependent)

Color develops based on analyte concentration

Read at appropriate wavelength

Create standard curve

Calculate sample concentrations using standard curve

Enzyme Assays

Examples: LDH, GPT, GGT, GOT, CK, ALP

Substrate or product absorbs light in visible or UV range

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH)

Reaction: Lactate + NAD → Pyruvate + NADH + H⁺

NADH absorbs at 340 nm; NAD does not

Forward reaction monitored by measuring increase in absorbance at 540 nm

Spectrophotometer QC – Maintenance / Routine Checks

Washing, blanking, water check

Temperature check

Alignment of the needle

Cuvette dispenser

Bulb lifetime

Piping (contamination, kinks, solids)

Waste disposal and container washing

Washing of pipes

Spectrophotometer QA

Periodic Checks (Monthly or more)

Wavelength accuracy: Using standard absorbing solutions or filters with known absorbance maxima

Stray light: Caused by scratches or dust in the light path, λ outside the transmitted band

Linearity: High concentrations may not be linear; dilution and calibration curve needed

Filters: Checked and replaced as needed

Spectrophotometers should be able to automatically dilute samples when necessary

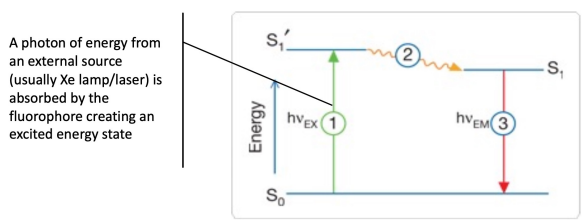

Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Based on the ability of certain molecules (fluorophores) to absorb light at one wavelength (excitation) and emit light at a longer wavelength (emission)

Fluorescence

Some molecules absorb energy from photons and move to an excited state

When they return to the ground state, they release a photon as fluorescence emission

Fluorophores

Molecules that can be excited by light of a particular wavelength, absorb photons, and emit light at a different wavelength

Rigid planar structure

Highly conjugated system with alternating single and double bonds

Condensed fused-ring system containing one or more heteroatoms

Presence of electron-donating groups (e.g., –OH, –NH₂)

Presence of electron-accepting groups conjugated with the donating groups

Biological Fluorophores

Endogenous Fluorophores

Exogenous Fluorophores

Endogenous Fluorophores

Amino acids

Structural proteins

Enzymes and co-enzymes

Vitamins

Lipids

Porphyrins

Certain metals

Exogenous Fluorophores

Cyanine dyes

Drugs, both medicinal and illegal

Pollutants

Photosensitizers

Molecular markers, e.g., GFP

Applications of fluorophores

Immunofluorescence

Cytogenetics: FISH

Flow cytometry

Fluorescent immunoassay

DNA sequencing

Determination of fluorescent drugs in low-dose formulations in the presence of non-fluorescent excipients

Carrying out limit tests where the impurity is fluorescent

Studying the binding of drugs to components in complex formulations

Widely used in bioanalysis for measuring small amounts of drug and studying drug-protein binding

Immunofluorescence - Applications of fluorophores

Important immunochemical technique that utilizes fluorescence-labelled antibodies to detect specific target antigens

Used widely in both scientific research and clinical laboratories

Allows for excellent sensitivity and amplification of signal

Analysis of samples labelled with fluorescence-labelled antibodies must be performed using a fluorescence microscope or other type of fluorescence imaging

Cytogenetics: FISH - Applications of fluorophores

= Fluorescence in situ hybridization

Involves unwinding of the double helix structure and binding of fluorescently labeled DNA probes to specific sequences in sample DNA

The fluorescent probes are nucleic acids labeled with fluorescent groups and can bind to specific DNA or RNA sequences

This allows visualization of where and when a specific DNA sequence exists in cells

Flow cytometry - Applications of fluorophores

Operates on the principles of light scattering, excitation, and emission

Fluorescently tagged cell components are excited when they pass through a laser beam, producing light of different wavelengths

The fluorescence is used to analyze cellular properties such as size, granularity, and protein expression

Fluorescent immunoassay - Applications of fluorophores

Utilizes fluorescent molecules as labels to measure antigen concentrations

Time-resolved immunoassay methods allow overcoming background fluorescence

DNA sequencing - Applications of fluorophores

Fluorescent dyes label nucleotides in sequencing reactions:

red for thymine

green for adenine

blue for cytosine

yellow for guanine

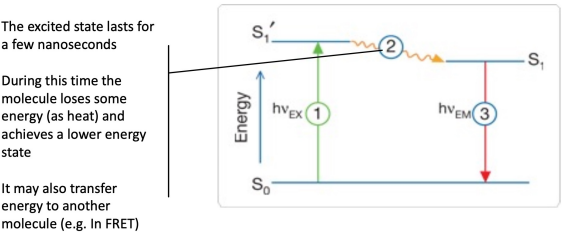

Fluorescence process

Stage 1: Excitation

Stage 2: Excited state lifetime

Stage 3: Fluorescence emission

Stage 1: Excitation

Stage 2: Excited state lifetime