Lecture Works Info (Exam 2)

1/12

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

13 Terms

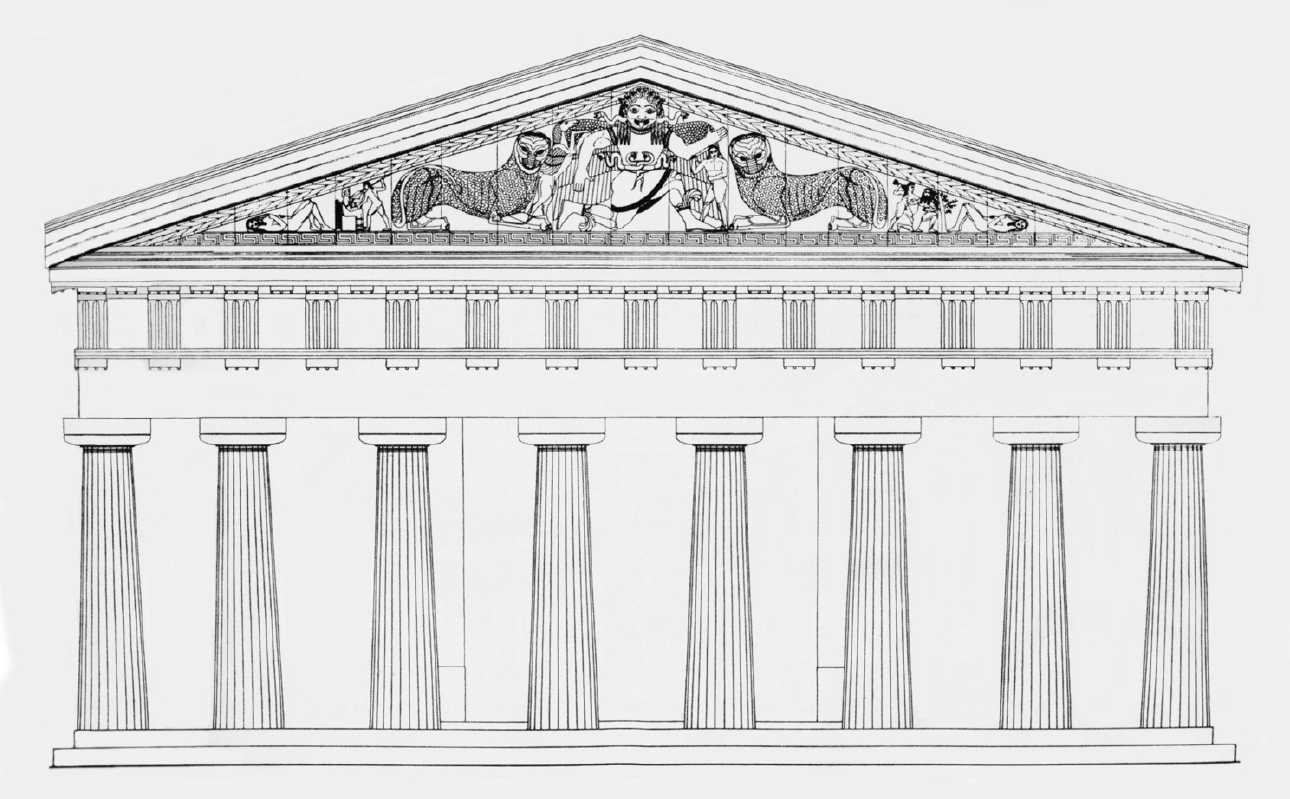

Temple of Artemis (Archaic Period), Corfu, ca. 580 BCE

This work held profound significance both symbolically and functionally. Its dedication to Artemis, the goddess of the hunt, childbirth, and wilderness, underscored its religious importance. The temple's architectural form, characterized by Doric columns and a peripteral colonnade, emphasized its grandeur and served as a beacon of Artemis's divine presence. The use of local limestone as the primary building material not only reflected the region's resources but also showcased the craftsmanship of ancient Greek artisans. Additionally, the inclusion of a pediment featuring Medusa, a powerful protective symbol, conveyed the temple's role as a sacred sanctuary offering refuge and spiritual guidance to worshippers. In essence, its architectural magnificence, religious iconography, and material composition, functioned as a physical embodiment of devotion and a center for communal worship and religious rites dedicated to Artemis during the Archaic Period.

Function was to house the cult statue of a god and to provide a place to display and store dedications (votive offerings)

First building to incorporate all elements of Doric style, all in stone

West pediment: oldest decorated pediment in Greece

Medusa: gorgoneion with Archaic features, Knielauf pose, leopards-Artemis as huntress and protector of beasts

Synoptic narrative: Pegasus, Chrysaor

Scene from trojan war, titanomachy

Narrative (trojan war = Greek heroism)

Narrative (Titanomachy=power of the Olympian gods)

mix of meanings (ideas) and functionality - an early period of “experimentation”?

apotropaic

Zeus attribute (lightening?) striking Titan

Parthenon (Classical Period), Athens, 432 BCE

This work held profound cultural, religious, and political significance. Dedicated to the goddess Athena Parthenos, it served as a symbol of Athenian power, wealth, and artistic achievement. Its architectural form, characterized by Doric columns, a pedimental sculpture program, and intricate friezes, reflected the ideals of classical Greek architecture and embodied the city-state's democratic values. The extensive use of Pentelic marble, quarried from Mount Pentelicus, not only showcased Athens' resources but also highlighted its prosperity and cultural sophistication. Furthermore, the it’s sculptural program, including the iconic frieze depicting the Panathenaic procession and the monumental statue of Athena Parthenos housed within, celebrated Athens' patron goddess and reinforced her role as protector and patroness of the city. In its period of production, this work symbolized Athenian civic pride, religious devotion, and cultural identity, functioning as a monumental temple, treasury, and symbol of Athenian democracy and imperial ambition.

Temple of Athena Parthenos (Athena the Virgin)

Architects: Iktinos and Kallikrates

Pentellic marble

Harmonious proportions: I = 2w + 1

peristyle, pronaos, naos, opisthodomoi

Statue of Athena Parthenos

Sculptor: Pheidias

Height: ca. 40’ huge

Description by Pausanias: Chryselephantine construction, helmet, Nike, Spear, Shield + serpent (Erecthonius), birth of Pandora, Peplos + aegis w/gorgoneion

Tilted columns with entasis

upward curvature of stylobate, upward curvature of architrave, slight inward angle of columns, less distance between end columns

ideas of stability, perfection, life

sculptural decoration: doric with an ionic twist

While the external structures (Doric frieze: outside the peristyle) of the temple were Doric, the central structures (Ionic frieze: inside the peristyle) of the temple made use of Ionic elements.

Ionic frieze, Doric Metopes (doric order)

A sculptured Ionic frieze encircled the whole of the cella and replaced the Doric frieze over the pronaos and opisthodomos and the treasury contained tall, thin Ionic columns. In addition, all 92 of the external Doric metopes were decorated with architectural sculpture.

The metopes

Celebrate the victory of civilization (order) over barbarians (chaos)

West: amazonomachy: metopes: battles of greeks and amazons; pediment: dispute of athena and poseidon

North: Sack of Troy: battle of Troy

East: Gigantomachy: metopes: battle of gods and giants; pediment: birth of Athena

South: Centauromachy: battle of Lapiths and centaurs

Reconstructed West pediment: contest between Athena vs. poseidon

reconstructed east pediment: the birth of Athena

all mythological metaphors for the greek defeat of the persians in the persian wars

Three goddesses: part of the decoration of the east pediment (birth of athena)

leto (artemis’ mom), artemis, and aphrodite

attributed to pheidias; examples of the classical wet drapery style

shows traces of egyptian blue from imaging technique called visible induces luminescence (VIL)

polychromy on parthenon ionic frieze

Ionic frieze: representation of the panathenaic procession

part of the panathenaia - annual festival for athena

route of the panathenaic procession: acropolis - agora - dipylon gate

Temple of Apollo (Hellenistic Period), Didyma, ca. 300 BCE

Constructed around 300 BCE during the Hellenistic Period, the Temple of Apollo in Didyma held profound religious and cultural significance in the ancient Greek world. Its monumental form, characterized by a vast colonnaded structure and an imposing entrance, conveyed the grandeur and majesty associated with divine worship. The extensive use of marble, sourced from nearby quarries, not only showcased the region's wealth but also emphasized the temple's sacred nature. The temple's iconography, centered around the worship of Apollo, the god of prophecy and music, reflected the Hellenistic fascination with oracles and religious sanctuaries. Additionally, the temple's context as part of the Sanctuary of Apollo at Didyma, a renowned center of pilgrimage and oracular consultation, underscored its importance as a spiritual and cultural hub, where worshippers sought guidance and divine favor. Overall, the Temple of Apollo in Didyma served as a monumental testament to ancient Greek religious devotion, architectural innovation, and cultural identity during the Hellenistic Period.

greek architects paionios and daphnis: never fully completed

dipteral design (hellenistic principle of reduplication)

Temple steps and pronaos; columns 6ft in diameter

The Temple of Apollo at Didyma: entrance to the north barrel-vaulted tunnel

hypaethral interior, looking west

play of light and shadow

shrine of apollo at ground level

hypaethral interior, looking east

2 corinthian engaged columns

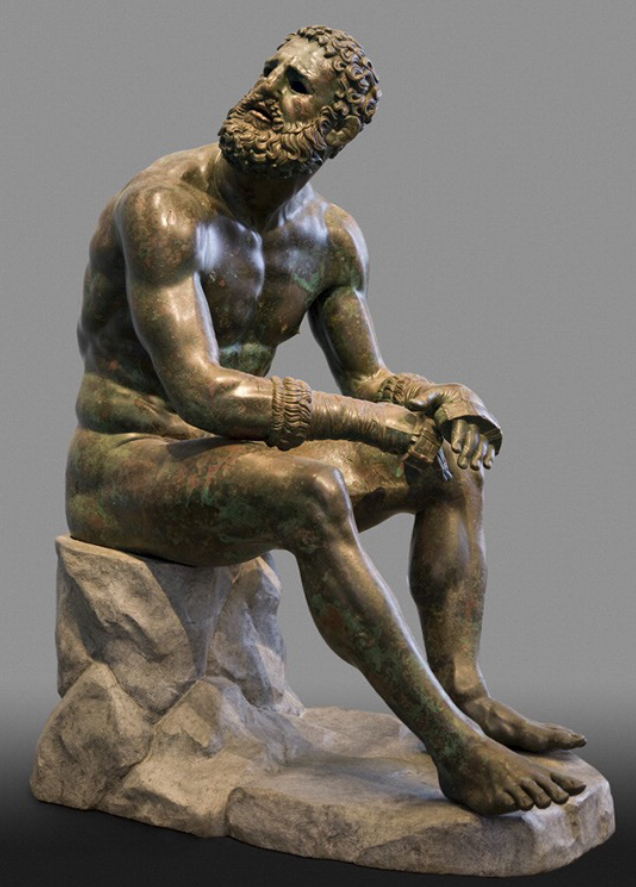

Terme Boxer (Hellenistic Period), Rome, ca. 250 BCE

Terme Boxer, created around 250 BCE during the Hellenistic Period in Rome, embodies a powerful narrative of athleticism, suffering, and human emotion. Its iconography, depicted through the exquisite detail of the sculpture, captures a wounded boxer in a moment of exhaustion and defeat, symbolizing the physical and psychological toll of ancient sporting competitions. The sculpture's form, with its lifelike portrayal of the boxer's muscular anatomy and facial expression, evokes a sense of realism and emotional depth, inviting viewers to empathize with the subject's struggle. Crafted from bronze, a material associated with strength and durability, the Terme Boxer exemplifies the technical mastery of ancient sculptors and the wealth and sophistication of Roman patrons. Contextually, the sculpture likely adorned the public baths or gymnasiums of ancient Rome, serving as both a decorative embellishment and a poignant reminder of the human experience in the realm of sports and competition. In its period of production, the Terme Boxer not only celebrated the athleticism and physical prowess of ancient athletes but also conveyed the universal themes of perseverance, vulnerability, and the human condition.

cauliflower ear, bandaged hands, cuts on face

shows a real boxer

new ideal, sensitive to human experience, human face as a window to the soul

different commemorations of victorious athletes compared to classical sculpture

heightened pathos - a quality that evokes pity of sadness

Tomb of the Leopards (Etruscan Period), Tarquinia, ca. 470 BCE

The Tomb of the Leopards, dating back to around 470 BCE during the Etruscan Period in Tarquinia, holds significant cultural and religious meaning. Its intricate iconography, depicted through frescoes covering the interior walls, portrays scenes of revelry, banqueting, and ritualized gestures, symbolizing the Etruscan beliefs surrounding the afterlife and the passage of the deceased into the realm of the gods. The tomb's form, with its subterranean layout and chambered structure, reflects Etruscan burial practices and the importance placed on honoring and commemorating the deceased within a sacred space. Crafted from durable materials such as tufa rock and adorned with vibrant pigments, the Tomb of the Leopards exemplifies the artistic and technical skill of Etruscan craftsmen and their ability to create enduring works of funerary art. Contextually, the tomb served as a place of burial and commemoration for the deceased, while also functioning as a site for ritualistic ceremonies and ancestor veneration, reinforcing social and religious bonds within the Etruscan community. In its period of production, the Tomb of the Leopards not only provided insight into Etruscan funerary practices and beliefs but also served as a testament to the enduring legacy of Etruscan civilization and its rich artistic and cultural heritage.

Necropolis

Tympanum

etruscan symposia occuring tomb-side? Meant to honor the dead rather than celebrate the living?

Theater of Pompey (Roman Republic), Rome, 55 BCE

The Theater of Pompey, constructed in 55 BCE during the Roman Republic, held significant political, social, and cultural importance. Its iconography, represented through architectural elements such as the grand facade and monumental seating arrangements, symbolized the power and prestige of its patron, Pompey the Great, who commissioned the theater as a means of solidifying his political influence and garnering public support. The theater's form, with its semicircular layout and tiered seating, exemplified Roman engineering ingenuity and architectural innovation, providing a space for large-scale public gatherings, theatrical performances, and political speeches. Crafted from durable materials like concrete, travertine, and marble, the Theater of Pompey showcased the wealth and resources of the Roman elite while ensuring the longevity and functionality of the structure. Contextually, the theater served as a focal point for civic and cultural activities in ancient Rome, functioning as a venue for both entertainment and political discourse, where citizens could come together to witness spectacles, engage in public debate, and participate in the democratic process. In its period of production, the Theater of Pompey not only reflected the grandeur and ambition of Pompey the Great but also epitomized the central role of public entertainment and political spectacle in Roman society during the Republican era.

Pompeius Magnus (the great) - highly successful military general during the late roman republic; close friend-turned-enemy of Julius Caesar

use of concrete to construct a cavea w/o a hillside in the campus martius

Pozzolana (volcanic sand) from pozzuoli near naples

mortar (sand, lime, water) + aggregate (stone, brick) and poured into wooden frameworks

first permanent theater in Rome

temple of Venus Victrix (venus the conqueror)

venus victix = pompey’s patron deity

assoc. porticos and gardens decorated with artworks brought back as spoils of war from pompey’s military compaigns in the east (including greece)

Denarius of Julius Caesar (Roman Republic), Rome, 44 BCE

The Denarius of Julius Caesar, minted in 44 BCE during the Roman Republic, held profound political and propagandistic significance. Its iconography, featuring a portrait of Julius Caesar on one side and symbols of military conquest on the other, conveyed Caesar's authority as dictator perpetuo and celebrated his military achievements, reinforcing his status as Rome's supreme leader. The denarius's form, a small silver coin with intricate engraving and inscriptions, served as a ubiquitous means of disseminating Caesar's image and message throughout the Roman Republic, facilitating widespread recognition and ideological influence. Crafted from silver, a precious metal associated with wealth and prestige, the denarius underscored Caesar's financial and political power, while also serving as a practical medium of exchange in the Roman economy. Contextually, the minting of the Denarius of Julius Caesar coincided with Caesar's consolidation of power and the demise of the Roman Republic, marking a pivotal moment in Roman history and signaling the transition to autocratic rule under the principate. In its period of production, the Denarius of Julius Caesar functioned as a potent symbol of Caesar's authority and as a tool for asserting his political dominance and shaping public perception in the tumultuous final years of the Roman Republic.

coins were very important for understanding ancient portraiture because they combine text and image in an inseparable way

Corona triumphalis

obverse: head of caesar

legend: dictator perpetuo Caesar

reverse: venus genetrix holding victoria and a scepter

legend: Lucius Buca

venus as JC’s divine ancestor

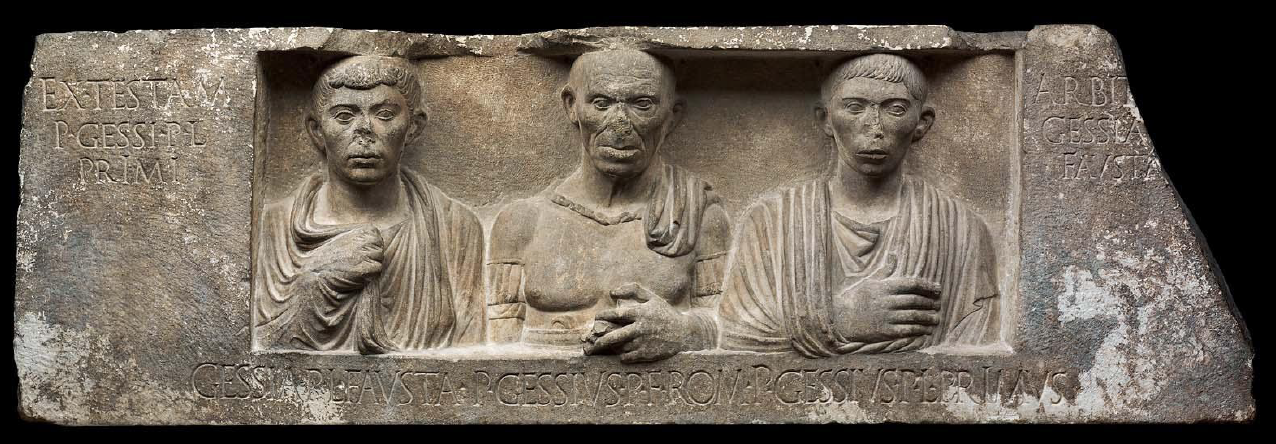

Funerary Relief of the Gessi (Roman Republic), Rome, ca. 50 BCE

The Funerary Relief of the Gessi, created around 50 BCE during the Roman Republic, carries profound significance in its portrayal of familial bonds, social status, and religious beliefs. Its iconography, depicted through the relief's sculpted figures of a Roman family, signifies the importance of ancestry and commemoration in Roman society, while also conveying the deceased's connection to the divine realm through the presence of deities and ancestral spirits. The relief's form, with its high relief sculpture and detailed carving, exemplifies the artistic skill of Roman craftsmen and their ability to capture lifelike representations of human figures and emotions, enhancing the viewer's sense of empathy and engagement with the scene. Crafted from marble, a material associated with durability and prestige, the relief not only served as a marker of the deceased's social status and wealth but also ensured the longevity and permanence of their memory within the funerary context. Contextually, the Funerary Relief of the Gessi would have adorned a tomb or funerary monument in Rome, serving as a visual tribute to the deceased and as a focal point for mourning, remembrance, and religious rites within the family and community. In its period of production, the relief functioned as both a commemorative tribute to the deceased and as a visual expression of Roman funerary customs, social values, and religious beliefs, serving to perpetuate the memory and legacy of the deceased for generations to come.

a window relief

Verism

Cuirass, paludamentum

publius

liberta/libertus

filius - freeborn son

clothing and pose celebrate status as roman citizens

toga (only worn by men with roman citizenship)

Palla; in a pudicitia pose (only worn by women with Roman citizenship)

once freed, enslaved persons attained new rights such as

became roman citizens

hold lower political offices and vote (men)

serve in the army (men)

could have a legal family

could marry and bear freeborn children (filii/filae) with the right to inherit

could attain wealth through employment (artists, builders, bakers, tutors)

Augustus (Julio-Claudian), Primaporta, ca. 20 CE

The Augustus statue from Primaporta, dating to around 20 CE during the Julio-Claudian period, held profound political, ideological, and propagandistic significance. Its iconography, featuring Augustus in the guise of a triumphant general, symbolized his role as Rome's first emperor and divine ruler, while also conveying his authority, wisdom, and piety through the inclusion of symbolic attributes such as the armor and the cupid at his feet. The statue's form, with its idealized portrayal of Augustus's youthful and powerful physique, reflects the classical aesthetic ideals of beauty, strength, and harmony, enhancing the ruler's image as a paragon of Roman virtues and ideals. Crafted from marble, a material associated with luxury and prestige, the statue not only emphasized Augustus's status as a distinguished statesman and patron of the arts but also ensured the longevity and permanence of his memory and legacy within the Roman collective consciousness. Contextually, the Augustus statue from Primaporta served as a visual assertion of Augustus's authority and legitimacy as Rome's ruler, while also promoting his imperial agenda and fostering loyalty and allegiance among the Roman populace. In its period of production, the statue functioned as a powerful tool for shaping public perception, reinforcing imperial ideology, and legitimizing Augustus's reign as the founder of the Roman Empire.

found in the villa of Livia in Primaporta

Julio-Claudian “comma locks”

represent roman leaders and “power hair”

No more verism, augustan (greek) classicizing style

youthful face

no signs of aging over years

roman adlocutio pose: contrapposto and right arm raised and hand either pointing or extended outward.

orator

military commander

hero/ god-like - bare feet

divine ancestry - cupid

cuirass - visual representation of augustus and his “pax romana”

including caelus, aurora, gallia capta, diana, tellus, apollo, hispania capta, and sol

Ara Pacis (Julio-Claudian), Rome, ca. 9 CE

The Ara Pacis, erected around 9 CE during the Julio-Claudian period in Rome, symbolized peace, prosperity, and the renewal of the Roman state under Augustus's rule. Its iconography, depicted through intricate relief sculptures, portrayed scenes of abundance, fertility, and divine blessings, celebrating the Pax Romana established by Augustus and his dynasty. The monument's form, with its imposing altar and surrounding enclosure, served as a physical and symbolic center for religious ceremonies, state rituals, and public gatherings, reinforcing the ideals of unity and stability promoted by Augustus's regime. Crafted from marble, a material associated with luxury and permanence, the Ara Pacis not only showcased Augustus's wealth and power but also served as a lasting monument to his vision of a harmonious and prosperous Roman Empire. Contextually, the Ara Pacis was erected during a period of political consolidation and cultural renewal, marking a pivotal moment in Roman history and cementing Augustus's legacy as Rome's first emperor and the architect of its golden age. In its period of production, the Ara Pacis functioned as a powerful symbol of Augustan ideology, promoting peace, piety, and civic virtue while also reinforcing the authority and legitimacy of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Marble

original polychromy

commissioned by the senate to celebrate Ara’s successful campaigns in hispania and gaul

functioned as an altar, designed to look traditional with wooden components, garlands, etc. but rendered in stone

lower registers: plants and animals

upper registers: historical narratives

celebrated augustus and his new rome with an emphasis on peace, order, and prosperity

scrolling vegetation: fertility/ abundance and harmony/order

the natural world tamed

south side: imperial procession

augustus (capite velato), priests (flamines), sacrificial animals

agrippa, livia, tiberius, extended family

Livia in the Guise of Ceres (Julio-Claudian), Rome, after 14 CE

Livia in the Guise of Ceres, created in Rome after 14 CE during the Julio-Claudian period, held multifaceted significance as a representation of imperial power, fertility, and divine patronage. Its iconography, featuring Livia, the wife of Augustus, depicted as the goddess Ceres, symbolized her association with agriculture, abundance, and the nurturing of the Roman state. The sculpture's form, with Livia depicted in the guise of a goddess, exemplified the idealized portrayal of imperial women as divine figures, reinforcing their elevated status and influence within Roman society. Crafted from marble, a material associated with luxury and prestige, the sculpture not only showcased Livia's wealth and social standing but also served as a visual expression of her connection to the divine realm and her role as a benefactor of the Roman people. Contextually, the sculpture would have been displayed in a public or religious setting, serving to promote the imperial cult and to legitimize Livia's authority and dynastic succession within the Julio-Claudian dynasty. In its period of production, Livia in the Guise of Ceres functioned as a potent symbol of imperial ideology, female virtue, and divine favor, contributing to the cult of the empress and the glorification of the Julio-Claudian regime.

Akin to a disguise (shows someone or something as someone/something they are not). In Roman portraiture, often representations of mortal individuals as gods.

Divine guises are typically selected because aspects of the character of the god/goddess are considered analogous to aspects (real or alleged) of the mortal’s character.

Ceres (Demeter) as goddess of agriculture and motherly love

floral garland

sheaves of wheat; seed pods

cornucopia

relating back to Augustus’ cuirass

Palla

Nodus hairstyle: external indication of inner restraint and modest character-front loop and bun

Stola

Contrapposto

Capite Velato

Infula

Livia as representing the Augustan ideal of a roman woman-a modest, productive, member of society (bearer of children)

Colosseum (Flavian), Rome, 80 CE

The Colosseum, completed in 80 CE during the Flavian period in Rome, embodied the grandeur, power, and entertainment of the Roman Empire. Its iconography, represented through its colossal size and distinctive elliptical shape, symbolized Roman engineering prowess and imperial dominance, serving as a monumental testament to the might of the Flavian dynasty. The amphitheater's form, with its tiered seating and arena floor, facilitated the staging of elaborate spectacles, including gladiatorial combats, wild animal hunts, and naval battles, offering entertainment to the masses and reinforcing the social order and political control of the ruling elite. Crafted primarily from travertine limestone and concrete, the Colosseum showcased the technological innovation and architectural ingenuity of ancient Rome, while also emphasizing the durability and permanence of Roman civilization. Contextually, the Colosseum was built on the site of Nero's former palace, the Domus Aurea, serving as a deliberate repudiation of his excesses and a statement of Flavian legitimacy and populism, as it provided free public entertainment to the citizens of Rome. In its period of production, the Colosseum functioned as a monumental symbol of Roman power, entertainment, and social cohesion, shaping the collective identity and cultural legacy of the Roman Empire for centuries to come.

Started by Vespasian in 72 Ce, finished by Titus

First games held in 80 CE, known as the flavian amphitheater

man-made lake from Domus Aurea boating venue drained shortly after Nero’s death to make way for the amphitheater now called the Colosseum

first permanent amphitheater in Rome, 2nd in italy

concrete and brick with travertine revetment

rings of barrel vaults hold up the cavea

sat 50k people

stratified seating-

wooden upper tier (very poor, women, and slaves)

marble lower seating (middle/upper classes)

floor covered with sand or flooded with water; concealed complex machinery and rooms for combatands (gladiators, animals, etc.

Orders of the Colosseum

Top: Corinthian (engaged columns + pilasters)

Middle: Ionic

Bottom: Tuscan

Arch of Titus (Flavian), Rome, 82 CE

The Arch of Titus, erected in 82 CE during the Flavian period in Rome, held profound political, religious, and commemorative significance. Its iconography, depicted through relief sculptures, prominently featured scenes of Roman military triumph, including the spoils taken from the Siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE, symbolizing Titus's victory and the subjugation of Judea. The arch's form, with its monumental triumphal archway and imposing structure, served as a physical and symbolic gateway to the Roman Forum, commemorating Titus's military achievements and reinforcing the prestige and authority of the Flavian dynasty. Crafted from Pentelic marble and travertine, the arch showcased the wealth and power of the Roman Empire, while also symbolizing the durability and permanence of Roman civilization. Contextually, the Arch of Titus was built during a period of political consolidation and imperial expansion under the Flavian emperors, serving as a visual assertion of Roman dominance and as a reminder of the martial prowess and divine favor bestowed upon Titus by the gods. In its period of production, the Arch of Titus functioned as a powerful symbol of military victory, imperial authority, and dynastic legitimacy, shaping the public perception and memory of Titus's reign and the Flavian era in Roman history.

A monument to the life and afterlife of a Flavian emperor

Inscription in the Attic

The Senate

and people of rome (SPQR)

(dedicate this) to the divine titus vespasian augustus son of the divine vespasian

vault

coffered vault of the arch of titus - apotheosis

freestanding arches - triumphal arches

a civic celebration awarded to an individual by the senate for his victory in a foreign war

the flavian triumph

triumphator relief

lictors, roma, quadriga, titus, victoria

fasces

first one historically awarded to romulus

during the republic, awarded to generals

during the empire, awarded only to the emperor and members of his immediate family

main event was a parade through the streets of Rome, ending at the temple of jupiter optimus maximus on the capitoline hill

parade showcased spoils including from the sacked 2nd temple of jerusalem, the golden menorah, the golden shewbread table, a copy of the Torah

Commemorated inside the arch of titus, on the walls below the vault

participants - prisoners of war, spoils with descriptive signs, artistic displays of battle (paintings, models)

the triumphator in a quadriga, with victoria holding a corna triumphalis

sacrificial animals (2 white oxen for jupiter)

officials and standard bearers

the army

Awarded to vespasian and titus by the senate for the suppression of a jewish revolt and the conquest of judea in 70 CE

an invitation to participate