prosocial behaviour

1/38

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

39 Terms

what is the definition + 2 features of prosocial behaviour

acts that are viewed positively by society, so will differ between culture

has positive social consequences + contributes to physical/psychological wellbeing of others

is voluntary + intended to benefit others (helpful + altruistic), e.g. acts of charity/rescue

what are 2 types of prosocial behaviour

types of prosocial behaviours differ due to motives

helping behaviour → acts that intentionally benefit someone else/a group, usually with an expectation of something in return (so not selfless)

altruism → acts that benefit another person rather than oneself, so without expectation of one’s own gain. means they are selfless, though it can be difficult to prove selflessness (due to private rewards)

what instigated research into pro-social behaviour

the Kitty Genovese murder → was attacked + murdered in public

shouted for help → 37 witnesses admitted to hearing her scream but failed to act

prompted research into what motivates + doesn’t motivate people to act

what is the general evolutionary perspective of prosocial behaviour

humans have an innate tendency to help others in order to pass our genes to the next generation → helping kin to improve their survival rates

potentially has evolutionary survival value → evidenced by animals also engaging in prosocial behaviour

what are Stevens et al. (2005)’s 2 explanations of prosocial behaviour in animals and humans

mutualism → benefits the co-operator as well as others; a defector (who doesn’t engage in such behaviour) will do worse than a co-operator due to not having the benefit of others

kin selection —> prosocial behaviour is biased towards blood relatives due to helping their own genes

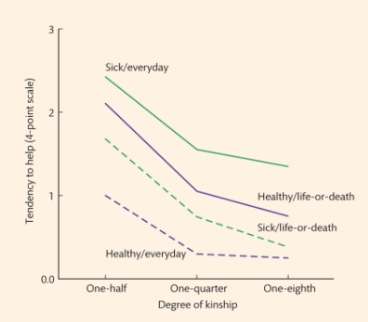

how did Burnstein et al. (1994) investigate kin selection in humans

participants were asked to rate how likely they were to help other people based on degree of kinship + how healthy/sick they were

found participants more likely to help the sick than the healthy in an everyday situation, but more likely to help the healthy in a life-or-death situation

scores increased with the degree of kinship → shows we may be more likely to help people likely to carry on our genetic line

what are 5 criticisms of evolutionary perspective

doesn’t account for people helping strangers, especially when prosocial behaviour doesn’t directly affect them

little empirical evidence → not possible to access evolutionary processes in a lab, instead based on how we perceive events in the past

doesn’t account for why we help in some circumstances but not others, e.g. in types of familial abuse

doesn’t account for humans differing from animals in terms of higher order reasoning → humans can consider ethics + determine whether helping someone is morally correct

doesn’t account for social factors e.g. learning/norms → may be more to do with how much time we spend with someone than biological relatedness

what are social norms + how do they relate to prosocial behaviour

social psychological reason as to why people engage in prosocial behaviour → social norms = social guidelines that establish what most people do in a certain context/what is socially acceptable

play a key role in developing + sustaining prosocial behaviour

are learned rather than innate → we help others as something ‘tells us’ we should

what is the reason people behave in line with social norms

conforming to social norms is often rewarded, leading to social acceptance, whether violating norms can be punished + result in social rejection

what are 3 social norms explaining why people engage in prosocial behaviour

reciprocity principle → we should help others who help us (return favour)

social responsibility → we should help those in need independent of their ability to help us

just-world hypothesis → if we believe the world is a just + fair place, if we come across anyone undeservedly suffering we help them to restore our belief in the world

how does social learning lead to the development of prosocial behaviour + what are the 3 ways children learn prosocial behaviour

childhood = critical period where we learn prosocial behaviour → how we learn to respond to others informs how we can help others, e.g. providing comfort. children learn prosocial behaviour through:

giving instructions

using reinforcement

exposure to models

what did Grusec et al. (1978) find in relation to giving instruction forming prosocial behaviour

found telling children what is appropriate behaviour establishes an expectation + guide for later in life

direct instruction is only useful if caregivers’ behaviour is consistent with their teachings (e.g. less likely to not litter if seeing caregiver litter)

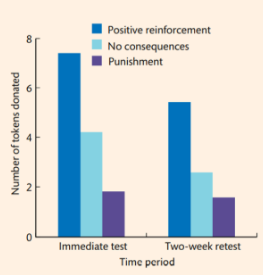

how does using reinforcement form prosocial behaviour + what did Rushton & Teachman (1978) find in relation to this

children are more likely to offer help again if they are rewarded for doing so → gives incentive for prosocial behaviour

found when children aged 8-11 observed an adult donating tokens in a game to a worse-off child + were positively reinforced, children donated a higher amount of tokens also

what did Rushton et al. (1976) find in relation to modelling in forming pro-social behaviour

concluded that exposure to models in media is more effective in shaping behaviour than reinforcement

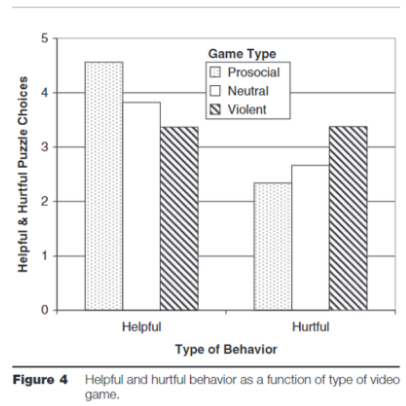

what did Gentile et al. (2009) find in relation to modelling in forming pro-social behaviour

when assigning children aged 9-14 to play prosocial, neutral or violent video games, found prosocial games increased short-term helping behaviour + decreased hurtful behaviour in a puzzle game

what is Bandura' (1973)’s social learning theory

argues against the idea that when a person observes a model + copies the behaviour, it’s just a matter of mechanical imitation

knowledge of what happens to the model in response to their behaviour (vicarious reinforcement!!), e.g. reinforcement or punishment, determines whether or not the observer will help

how did Hornstein (1970) investigate social learning theory on prosocial behaviour + what were the results

participants observed a model returning a lost wallet → model appeared pleased, displeased or displayed no strong reaction at helping

participant later came across a ‘lost wallet’ → those who observed the pleasant condition helped the most, while those who observed unpleasant condition helped the least

demonstrates modelling is not just about imitation → we need to know how the model is feeling about the behaviour to determine whether to imitate it

what is the bystander effect

people are less likely to help in an emergency when they are with others than when they are alone → the greater the number of bystanders, the less likely someone is to help

what did Latané & Darley (1968) find when investigating the bystander effect

simulated an emergency situation whilst completing a questionnaire → either presence of smoke or another participant suffering a medical emergency

found very few people intervened in the presence of others (confederates or participants), especially when others did not intervene

what is Latané & Darley (1968)’s 4 step cognitive model

contains 4 steps explaining how people decide whether to help:

attend to what is happening → if distracted event is not noticed

define event as an emergency → more likely if people are hurt/quickly deteriorating

assume personal responsibility → depends how competent/confident we feel

decide what can be done → less likely to help if one cannot think of a solution

what are 3 social processes contributing to the bystander effect

diffusion of responsibility → tendency of an individual to assume that others will take responsibility, even if no one helps if everyone is taking this mentality

audience inhibition → other onlookers may make the individual self-conscious about taking action, as they don’t want to appear foolish by overreacting

social influence → other people provide a model for action, so if they are unworried, the situation may appear less serious

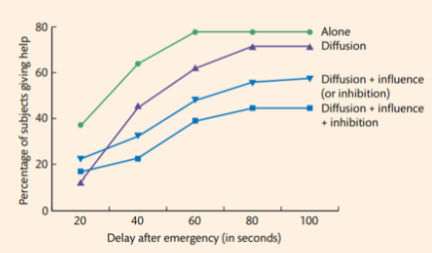

how did Latene + Darley (1976) investigate processes underlying the bystander effect + what were the 5 conditions involved

assessed participants responses to helping in an emergency bases on assignment to one of 5 conditions:

control → alone; cannot be seen/cannot see others

diffusion of responsibility → aware of another participant but cannot see them

diffusion of responsibility + social influence → aware of another participant; can see them in the monitor but cannot be seen themselves

diffusion of responsibility + audience inhibition → aware of another participant but can’t see them, and can be seen themselves

diffusion of responsibility, audience inhibition + social influence → aware of another participant, can see them + can be seen themselves

found the alone condition had the highest willingness to help in an emergency, and each factor that was added made participants less likely to help (audience inhibition + social influence were equal) + made helping behaviour more delayed

what is Piliavin et al. (1981)’s bystander calculus model + what are the 3 stages involved

theory on determining how we decide whether we should help or not → 3 stages include:

physiological processes → the empathic response to seeing someone in distress; the greater arousal, the greater chance we will help

labelling the arousal → we label this arousal as an emotion (e.g. distress or anger); distress at seeing someone suffer motives helping behaviour to reduce own negative experience

evaluation of physiological + cognitive factors of helping → performing cost- benefit analysis

what did Batson & Coke (1981) believe emphatic concern was triggered by

we are more likely to help a person when we believe we are similar to the victim + can relate to them

what did Darley & Batson (1973) outline as potential costs + benefits for helping behaviour

costs of helping included time, effort and personal risk (depending on the situation)

costs of not helping included empathy costs (causes distress to the bystander who empathises with victim) + personal cost (feeling guilt/blame at not helping a victim in distress

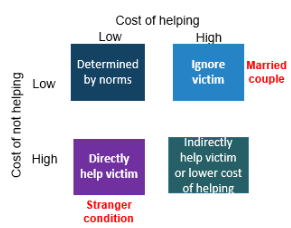

what is Piliavin et al. (1981)’s cost-benefit matrix

describes when we are more/less likely to help in an emergency

we are more likely to help when the costs of not helping = high and when the costs of helping = low

whether we help when both costs are low = determined by norms

we either indirectly help victim or lower the cost of helping when both costs are high

what did Shotland & Straw (1976) find when investigating bystander calculus model + what does this suggest

found when participants viewed a man + woman fighting (either a married couple or strangers), 65% of participants intervened in the strangers condition vs 19% in the married couple condition

explained by not wanting to intervene in a domestic situation due to potentially higher costs of helping (may not want you in their business

costs of not helping are perceived as higher in a stranger situation due to feeling more personal responsibility

how did Philpot et al. (2020) find evidence contradicting the bystander effect

reviewed CCTV recordings of street disputes in Lancaster, Amsterdam + Cape Town, and found at least 1 bystander intervened in 90% of cases

contrary to diffusion of responsibility, chances of intervening went up when the amount of bystanders increased

found limited cultural differences in proportion of intervening behaviour → suggests it’s a universal phenomenon, less influenced by crime rates (which would increase cost of helping)

what are 2 strengths of Philpot et al. (2020)’s research

large-scale test of effect in real-life scenarios → high ecological validity

effect consistently found across 3 different countries → generalisable

what are 2 limitations of Philpot et al. (2020)’s research

only assessed intervening in cities + more westernised countries → less generalisable to collectivist cultures, who may have different intervening rates

‘intervention’ is defined very broadly → lack of operationalisation

what are 4 perceiver-centred determinants of helping behaviour

personality → whether there is such thing as an altruistic personality

mood → individuals who feel good = more likely to help someone in need

competence → feeling more competent to deal with an emergency makes someone more likely to give help, as they feel they know what they’re doing

group membership → more likely to help someone with the same group identity as us

how did Bierhoff et al. (1991) investigate personality as determinant for helping + what 3 traits were people distinguished on

assessed people who helped in a traffic accident vs people who didn’t → found helpers + non-helpers were distinguished due to having higher levels of:

norm of social responsibility

internal locus of control

greater dispositional empathy

however this finding is correlational → not clear whether personality traits cause helping behaviour

what are 2 experimental findings in support of mood being a determinant of helping

Holloway et al. (1977) found increased willingness to help when having received good news → attributed to higher sensitivity to others + less inward thinking

Isen et al. (1976) → found teachers more successful on a task were more likely to contribute (+ contribute up to 7x more) later on at a fundraising event

what is an experimental findings contradicting mood as a determinant of helping

Isen et al. (1976) found increased willingness to help a stranger only occurred within first 7 minutes of positive mood induction, implying mood effects may be short-lived → this may be dependent on how good the mood induction technique was

what are 3 experimental forms of evidence that specific competency is a determinant of helping

Midlarsky (1976) → found people were more willing to help others move electrically-charged objects if told they had a high tolerance for electric shocks

Schwartz + David (1976) → found people were more likely to help capture a dangerous lab rat if told they were good at handling rats

Shotland + Heinold (1985) → found first-aid trained individuals were more likely to intervene when observing a stranger bleeding

shows competency in skills regarded as relevant increases likelihood of helping

how did Levine et al. (2005) investigate group membership as a determinant of helping + what were the findings

recruited 45 ManU fans who were taken on a short walk, during which they witnessed an emergency incident

confederate either wore a ManU, Liverpool or plain sports top + rate of helping the confederate was measured

found ManU fans were more likely to help other ManU fans than Liverpool fans/those not wearing a football shirt → shows increased helping behaviour for ingroup members

found in second study, where participants were informed they were taking part in a study about football fans (group membership widened), participants = more likely to help fans of either team than confederate in a plain top

what is an example of a recipient-centered determinant of prosocial behaviour

responsibility for misfortune → people are generally more likely to help people who are not responsible for their situation

relates to the just-world hypothesis → belief that the world is fair motivates people to help anyone who is undeservedly suffering, in order to restore tha belief

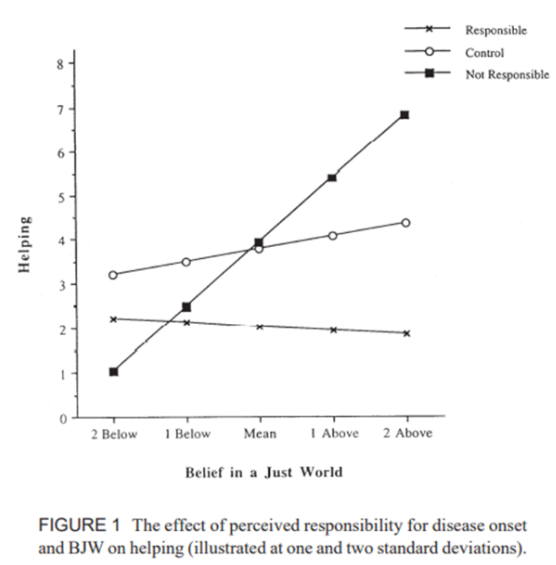

how did Turner DePalma et al. (1999) investigate the responsibility for misfortune determinant + what were the results

participants read a booklet about a fictional disease → was either caused by a genetic anomaly, the action of the individual, or no info was given

found helping behaviour significantly increased when person was not seen as responsible for contracting the disease

those with a higher belief in a ‘just world’ helped more only when person was not believed to be responsible for contracting the disease

how did Wakefield et al. (2012) investigate circumstances when receiving help is perceived negatively + what were the findings

recruited female participants, who were told that women may be stereotyped by men as being dependent (dependency stereotype) + were placed in a situation where they needed help (solving set of anagrams)

those made aware of the dependency stereotype were less willing to seek help, and those that did felt worse the more they sought

shows receiving help can be interpreted negatively if it confirms a negative stereotype about the recipient