The Menstrual Cycle

1/20

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

21 Terms

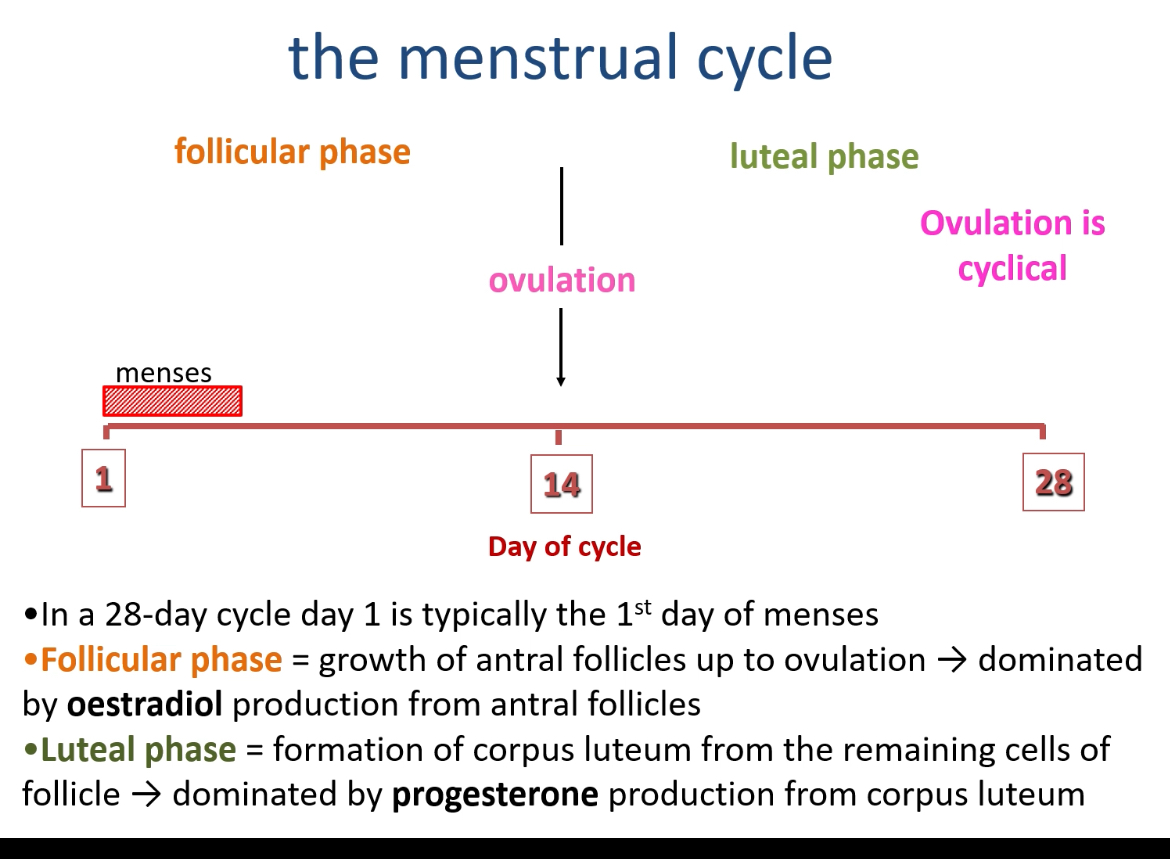

What are the two main phases of the menstrual cycle and what occurs in each?

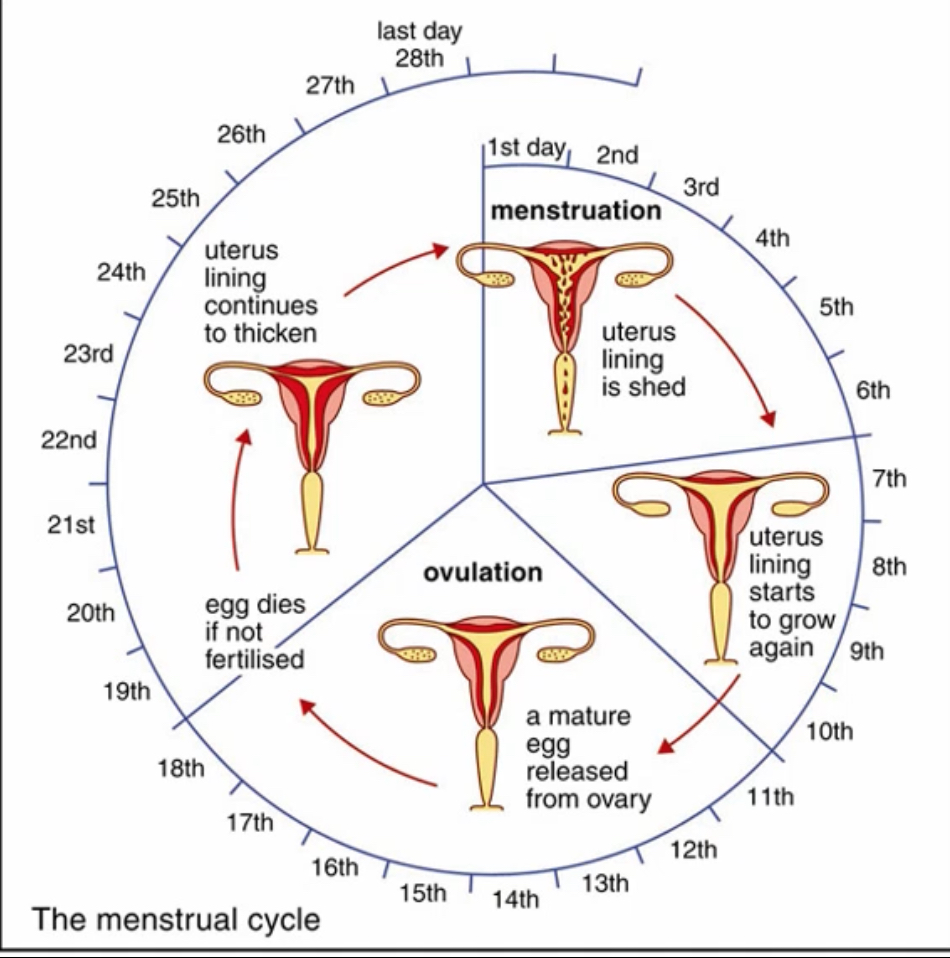

Follicular phase (Days 1–14): Begins on the first day of menstruation; involves growth of antral follicles and is dominated by oestradiol (E2) production from granulosa cells.

Luteal phase (Days 14–28): After ovulation, the follicle transforms into the corpus luteum (CL), which secretes progesterone, maintaining the endometrium and preparing for implantation.

How does oogenesis integrate with the menstrual cycle?

During follicular development, the primary oocyte (arrested in prophase I since birth) resumes meiosis I just before ovulation, forming a secondary oocyte and first polar body.

The secondary oocyte begins meiosis II but arrests again until fertilisation occurs.

What is the significance of folliculogenesis in the cycle?

Folliculogenesis ensures that one dominant follicle (DF) is selected and matured each cycle, leading to ovulation of a haploid oocyte capable of fertilisation

What are the main hormones regulating the menstrual cycle?

GnRH (from hypothalamus) – released in pulses.

FSH and LH (from anterior pituitary) – regulate follicle growth and ovulation.

Oestrogen and progesterone (from ovary) – provide positive and negative feedback to the hypothalamus and pituitary.

Why must GnRH be released in a pulsatile manner?

Continuous GnRH suppresses LH/FSH secretion, while pulsatile release stimulates their production—key for normal cyclicity.

Summary

1. Primordial germ cells (PGCs): the starting point

Primordial germ cells are specified very early in embryonic development. They are not eggs, not ovarian cells, and not yet located in the ovary. Their sole role is to become gametes. These cells represent the earliest origin of all eggs a woman will ever have.

2. Migration of PGCs to the fetal ovary

PGCs migrate from their site of origin to the developing gonads. In an XX fetus, the gonads differentiate into ovaries. Once the PGCs arrive in the ovary, they are no longer referred to as primordial germ cells because they have entered the ovarian developmental pathway.

3. Differentiation into oogonia (before birth)

Within the fetal ovary, PGCs differentiate into oogonia. Oogonia are diploid cells that divide repeatedly by mitosis, massively expanding the germ cell population. At peak fetal life, there are several million oogonia present in the ovary. This is the only stage at which the female germ cell population increases.

4. Entry into meiosis: formation of primary oocytes

Oogonia stop dividing by mitosis and enter meiosis I. Once meiosis begins, the cells are called primary oocytes. Each primary oocyte progresses through early meiosis I and then arrests in prophase I (diplotene). This arrest occurs before birth and can last for decades.

At this point, the oocyte is diploid, has duplicated DNA, and is paused partway through meiosis.

5. Formation of primordial follicles: oogenesis meets folliculogenesis

Each primary oocyte becomes surrounded by a single layer of flattened pre-granulosa cells. The primary oocyte together with these surrounding support cells forms a primordial follicle. This is the simplest follicle structure and the basic storage unit of the ovary.

Important distinction:

• The oocyte is the germ cell.

• The follicle is the structure that contains and supports the oocyte.

6. Atresia and establishment of the ovarian reserve

The majority of primordial follicles undergo atresia, a programmed cell death process. This occurs during fetal life, throughout childhood, and continuously during adult life. By birth, only around one to two million follicles remain, and by puberty this falls to roughly three to four hundred thousand.

No new oocytes or follicles are formed after birth; the ovarian reserve only declines.

7. Childhood: hormonal quiescence

During childhood, the hypothalamus releases very little GnRH, and the pituitary releases minimal FSH and LH. As a result, the ovaries remain largely inactive. Primordial follicles may initiate early growth but cannot mature fully.

There is no ovulation and no menstrual cycle.

8. Puberty: activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis

At puberty, the hypothalamus begins releasing GnRH in a pulsatile manner. GnRH stimulates the pituitary to release FSH and LH. These hormones now act regularly on the ovaries, allowing follicles to grow beyond the primordial stage. Follicles can reach early primary stages

Oestrogen production increases, driving secondary sexual characteristics and enabling menstrual cycling.

9. Monthly folliculogenesis begins: follicular phase

At the start of each menstrual cycle, falling progesterone from the previous cycle removes negative feedback on the pituitary, causing a selective rise in FSH. This recruits a cohort of primordial follicles into active growth.

Primary follicle stage

Granulosa cells become cuboidal and proliferate. The oocyte grows, and a zona pellucida forms around it. The oocyte is still a primary oocyte, arrested in prophase I.

Secondary (pre-antral) follicle stage

Granulosa cells form multiple layers. The surrounding stromal cells differentiate into theca cells, particularly the theca interna, which produces androgen precursors under LH stimulation.

Antral follicle stage

Fluid accumulates between granulosa cells, forming an antrum. The oocyte sits on a mound of granulosa cells called the cumulus oophorus. Granulosa cells convert theca-derived androgens into oestrogen under FSH control.

Dominant (Graafian) follicle

One antral follicle becomes highly sensitive to FSH and continues to grow even as FSH levels fall. All other follicles undergo atresia. The dominant follicle produces high and sustained levels of oestrogen.

Throughout all these stages, the cell inside the follicle remains a primary oocyte.

10. Oestrogen feedback and selection of ovulation

Moderately rising oestrogen exerts negative feedback on the pituitary, suppressing FSH more than LH. This ensures only one follicle survives. When oestrogen levels remain high for approximately two days, feedback switches from negative to positive, triggering the LH surge.

11. Ovulation: resumption of oogenesis

The LH surge causes the primary oocyte within the dominant follicle to complete meiosis I. This unequal division produces a large secondary oocyte and a small first polar body. The secondary oocyte immediately enters meiosis II and arrests at metaphase II.

Crucial clarification:

• The dominant follicle already existed before this division.

• The oocyte changes meiotic state, not follicular identity.

• The secondary oocyte does not become a follicle; it is released from the follicle.

The follicle ruptures and releases the secondary oocyte during ovulation.

12. Luteal phase: formation of the corpus luteum

After ovulation, the remaining follicular structure transforms into the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum secretes progesterone and some oestrogen. Progesterone converts the endometrium into a secretory, implantation-ready state and exerts strong negative feedback on GnRH, FSH, and LH.

13. Cycle outcomes

If fertilisation occurs

Sperm entry triggers completion of meiosis II, producing a true ovum and a second polar body. The developing embryo secretes hCG, maintaining the corpus luteum and progesterone production, preventing menstruation.

If fertilisation does not occur

The corpus luteum degenerates, progesterone and oestrogen levels fall, the endometrium is shed as menstruation, and loss of negative feedback allows FSH to rise, initiating the next cycle.

What triggers ovulation?

A massive LH surge caused by positive feedback from sustained high oestrogen levels triggers ovulation about 36 hours later.

What events occur during ovulation?

Follicular blood flow increases.

Proteolytic enzymes digest the ovarian wall.

The cumulus–oocyte complex (COC) is released and captured by fimbriae of the uterine tube.

What chromosomal events occur in the oocyte during ovulation?

LH surge induces completion of meiosis I, forming the secondary oocyte (haploid, n) and first polar body. The oocyte then arrests in metaphase II until fertilisation.

What happens to the follicle after ovulation?

The ruptured follicle collapses, forming the corpus luteum (CL) composed of luteinised granulosa and theca cells.

What does the corpus luteum secrete?

Progesterone: stabilises and thickens the endometrium, maintains uterine secretions, modulates tubal and cervical mucus, and supports early embryo transport.

Oestradiol: continues to aid endometrial growth.

What maintains the corpus luteum if pregnancy occurs?

hCG, secreted by the embryo’s syncytiotrophoblast, binds to LH receptors to maintain the CL until placental takeover (~week 10).

What happens if fertilisation does not occur?

The CL degenerates after ~14 days due to lack of hCG → progesterone and oestrogen levels fall, removing negative feedback → FSH rises → new follicular phase begins.

What is menstruation physiologically?

Withdrawal of progesterone causes vasoconstriction and shedding of the endometrial functional layer, marking Day 1 of a new cycle.

How can ovulation be detected clinically or at home?

Basal body temperature (BBT): rises by ~0.5–1°C after ovulation (due to progesterone).

Cervical mucus: becomes clear, stretchy (“spinnbarkeit”), and sperm-friendly near ovulation.

Ovulation kits: detect urinary LH (and sometimes oestrone-3-glucuronide, E3G).

Ultrasound: measures follicle diameter for ovulation induction monitoring.

What is the “fertile window”?

≈ 6 days: 5 days before ovulation (sperm survival) + 1 day after (egg lifespan).

Used in natural family planning or fertility awareness methods.

Why does only one follicle become dominant?

Because it develops more FSH receptors, gains LH receptors, and produces more oestradiol, which suppresses FSH and starves competing follicles.

What are E1, E2, and E3?

Forms of oestrogen:

E1 (oestrone): weaker; post-menopause.

E2 (oestradiol): strongest; main reproductive oestrogen.

E3 (oestriol): dominant in pregnancy.

What is “luteinisation”?

Transformation of granulosa and theca cells into luteal cells after ovulation, enabling progesterone production.

Why must GnRH pulses vary?

Frequency and amplitude of pulses determine whether FSH or LH dominates:

Slow pulses → FSH

Rapid pulses → LH

What do clinical drugs target?

GnRH analogues: control LH/FSH release (e.g., fertility treatment, contraception).

Clomiphene (Clomid): blocks oestrogen receptors to increase FSH/LH for ovulation induction.

OCPs: maintain constant oestrogen/progesterone to suppress LH/FSH → no ovulation.