Neo-behaviourism

1/16

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

17 Terms

Positivism

Positivism emphasised observable data and rejected metaphysics However, strict positivism limited theoretical explanation.

Logical positivism

Solved this problem by distinguishing between empirical observations and theoretical terms, allowing theory as long as it was logically defined and empirically testable.

Logical positivism divides science into two levels: Developed by the Vienna Circle (around 1924)

Empirical level

Observable events

Measurable data

Theoretical level

Concepts that explain observations

Must be: Logically defined and Indirectly testable

The problem positivism created

Pure positivism says:

“If you can’t observe it, don’t talk about it.”

But science needs theory to: explain behaviour and make predictions.

The problems psychology faced

Psychology wanted to use concepts like:

Drive

Learning

Anxiety

Intelligence

But these are: Abstract, Invisible, Mental

Operationalism

Operationism, introduced by Bridgman, required that all scientific concepts be defined in terms of the operations used to measure them. Operationism helped shape neobehaviourism by permitting theory while maintaining objectivity and empirical testability.

Neobehaviourism

Neobehaviorism emerged from the combination of behaviorism and logical positivism. Neobehaviorists allowed the use of theory provided it followed the rules of logical positivism.

Learning = the primary mechanism through which organisms adapt to their environments.

How does neobehaviorism differ from early behaviorism?

Watson (Behaviorism) | Neobehaviorism |

Rejected theory | Allowed theory |

Anti-mentalism | Used theoretical constructs |

Focused on Stimulus–Response | Allowed intervening variables |

Strict objectivism | Logical positivism |

Edward Chase Tolman

Edward Chase Tolman was a neobehaviorist, but unlike Watson or Hull, he believed that: Behavior is purposeful, organised, and guided by mental representations. He called his approach intentional behaviorism.

Tolman:

Learning ≠ association

Learning = acquisition of knowledge

Reinforcement affects performance, not learning itself

According to Tolman:

The organism is active, not passive

It forms: Expectations about outcomes and beliefs about the environment

Classical behaviorism

Learning = strengthening Stimulus–Response associations

Reinforcement is necessary for learning

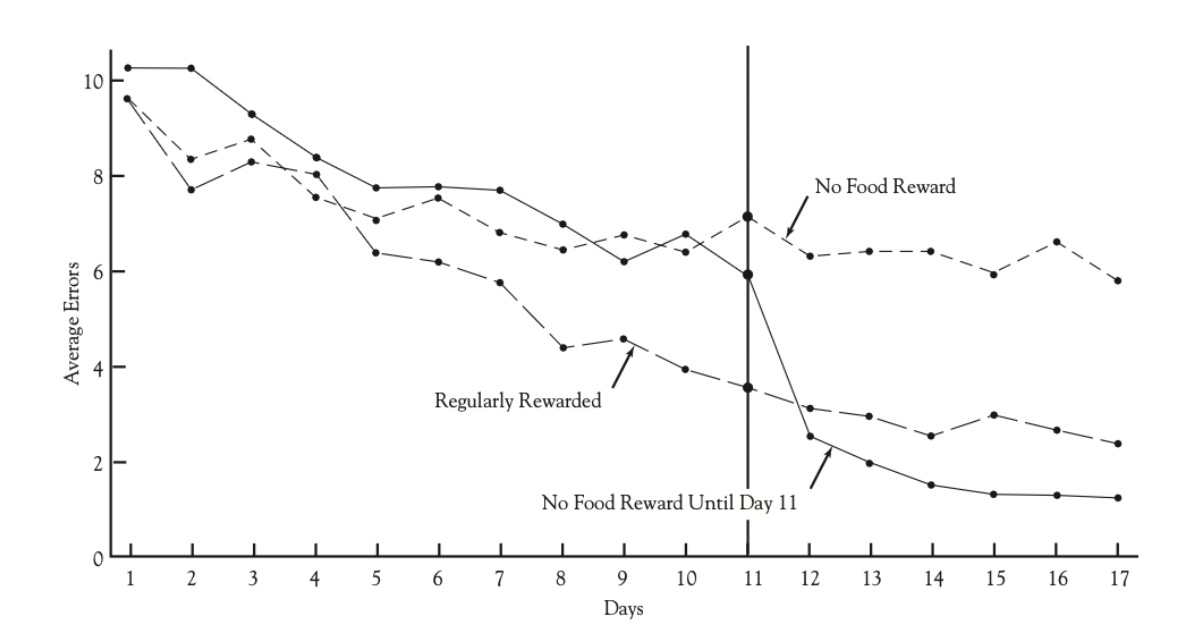

Tolman & Honzik (1930): Latent learning experiment

Rewarded group

Food at the end every day

Non-rewarded group

No food ever

Latent learning group

No food at first

Food introduced later (around day 11)

Results

Group 1: Gradual improvement

Group 2: Little improvement

Group 3: Sudden, dramatic improvement once food was introduced

Tolman concluded:

Rats learned the maze without reinforcement

Learning was latent (hidden)

Reinforcement only revealed what was already learned

This contradicted strict behaviorism.

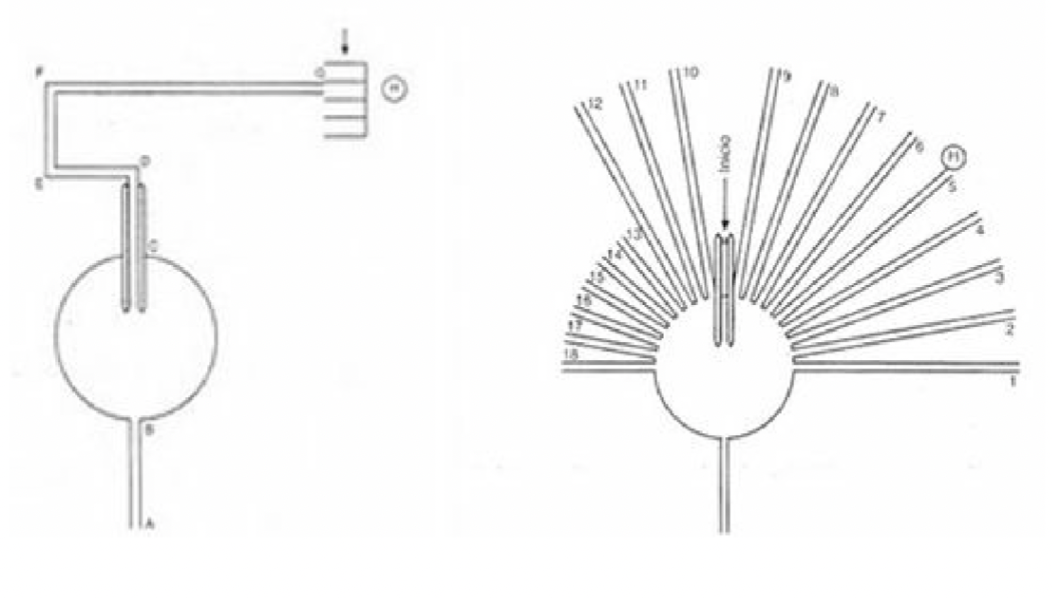

Cognitive map experiment (maze with shortcuts)

Rats learned a complex maze to reach food

Later, the usual path was blocked

Several new paths (shortcuts) were opened

Rats chose the path that:

Led most directly to the goal

Even if they had never used it before

Interpretation:

They formed a cognitive map of the maze

Behavior was guided by an internal spatial representation

Tolman – Intentional Behaviorism

Behavior is purposive & organized

Learning ≠ S–R associations

Active organism → expectations

Cognitive maps guide behavior

Latent learning → learning without reinforcement

Clark L. Hull: the drive theory

Drive theory (basic idea)

Hull believed that:

Organisms are motivated by biological needs

These needs create a drive (e.g., hunger, thirst)

Learning mechanism

Hull proposed the following sequence:

Stimulus → Drive → Response → Drive reduction → Reinforcement

Hull’s system was powerful but limited:

Could not explain:

Latent learning

Insight learning

Cognitive maps

Complex human behavior

Overly mechanistic

Reduced behavior to biological needs

Criticism of neo-behaviorism and transition to cognitive psychology

Excessive reductionism: complex phenomena were left behind.

Hypothetical constructs that are difficult to verify: cognitive maps and drives.

Theoretical rigidity: Hull’s models were too strict.

Partial successes: only effective in controlled contexts.

Behaviorism failed to explain cognition adequately.

Cognitive psychology:

Reintroduced the mind

Maintained scientific rigor

This marked a new paradigm in psychology.

Cognitive revolution (1950s–60s)

Chomsky (1959): language ≠ reinforcement

Miller (1956): memory limits (7 ± 2)

Simon & Newell: computational models

More Definitions

Latent learning - According to Tolman, learning that has occurred but is not translated into behavior.

Law of contiguity - Guthrie’s one law of learning, which states that when a pattern of stimuli is experienced along with a response, the two become associated. In 1959 Guthrie revised the law of contiguity to read, “What is being noticed becomes a signal for what is being done.”

Logical positivism - The philosophy of science according to which theoretical concepts are admissible if they are tied to the observable world through operational definitions.

Positivism - The belief that science should study only those objects or events that can be experienced directly. That is, all speculation about abstract entities should be avoided.