week 6; ADHD; symptoms and consequences

1/45

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

46 Terms

Characteristics of ADHD

Consists of hyperactivity, impulsivity and attentional problems

DSM-5: ADHD is ‘a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development’

often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities

often fidgets with or taps hands or feet or squirms in seat

recognises three ‘presentations’: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyper-active-impulses, combined

several symptoms have to be present before age 12 and manifest in more than one-context

ICD-11: ADHD (2010)- ‘ persistent patterns of inattentive and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that has direct negative impact on functioning’

statistics of ADHD

UK - currently 5%

ratio of boys:girls = 3:1 - the manifestation is different, so this ratio could just be referencing the rate of diagnosis rather than stating that it is more common in boys

symptoms continue into adulthood in 8-43% of cases (gender gap may narrow)

activity issues decline, attentional issues remain

a frontline treatment (children over 5/ adolescents and adults): DL-amphetamine or methylphenidate (NICE guidelines)

estimated medical and non-medical cost (children/ adolescent; UK) - £2.4 billion

The history of ADHD

in 1902, George Fredric Still (paediatrician)

Described 20 children with a “defect of moral control…. without impairment of intellect and physical disease”

moral control- they didn’t behave for the good of everybody but for the good of themselves

“the immediate gratification of self”

“fidgety….”

“incapacity for sustained attention”

1918-28, Encephalitis Iethargica epidemic

Many children who survived the encephalitis, showed abnormal behaviour - “Postencephalitic behaviour disorder”

Children became hyperactive, distractible, irritable, antisocial, destructive, unruly, and unmanageable in school

Because the symptoms came from this disease, it lead to the association of ADHD characteristics with brain damage….

1940’s/ 50’s, minimal brain damage

Assumption that minimal damage to the brain, even when it cannot be demonstrated objectively, causes postencephalitic-type behaviour disorder

1960’s, minimal brain dysfunction (MBD)

Became clear that hyperkinetic impulse disorder could occur in the absence of explicit brain damage

The Oxford International Study Group of Child Neurology advocated a shift in terminology from “minimal brain damage” to “minimal brain dysfunction”

moving away a bit from the association of the characteristics automatically comes from brain damage

1968, DSM II “hyperkinetic reaction of childhood”

MBD was considered too broad, leading to a focus on more specific symptoms (especially hyperactivity)

1980, DSM III “attention deficit disorder (ADD) (with or without hyperactivity)”

Throughout 70s, realisation that attentional problems were as significant, or more significant, than hyperactivity

could occur in two different ways and was the first to address that the disorder was attention-based

Hyperactivity was no longer an essential diagnostic criterion

Developed 3 separate symptom lists for inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity

1987 DSM III-R “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder”

Brought the symptom lists together, which is why it was ADHD not ADD

The symptom list was separated again (3 subtypes) in 1994

1994-2013

1994 DSM IV, 2000 DSM-IV-TR and 2013 DSM 5

the discovery of amphetamine

Dr Charles Bradley is credited with the discovery in the 1930s that amphetamine is efficacious in the treatment of ADHD whilst he was using it to stimulate the production of spinal fluid

what does ADHD have a negative effect on?

In general, the condition has a negative effect on:

Academic achievement

Occupational achievement

Social integration

Physical health

Mental health

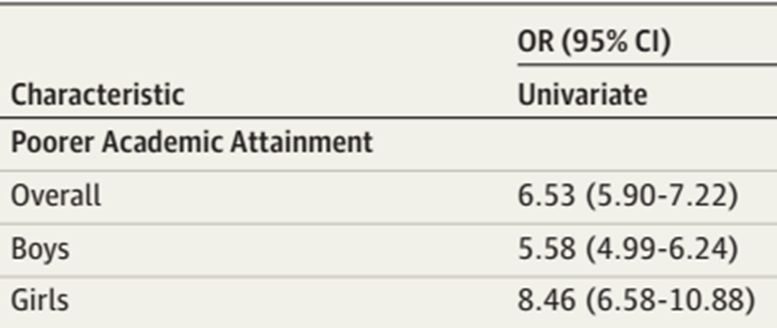

Fleming et al. (2017)

How does ADHD impact educational attainment?

4 Scotland-wide NHS databases

4 Scotland-wide school databases

School leavers 2009-13

Likelihood (OR) of leaving school with qualifications below GCSE level depending on if you were a student with ADHD or not

Sub-GCSE qualifications, they found that if you had ADHD you were 6.53% more likely to leave school with lower than GCSE level qualifications

Impacts of ADHD- DSM 5

DSM 5: There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with, or reduce the quality of, social, academic, or occupational functioning

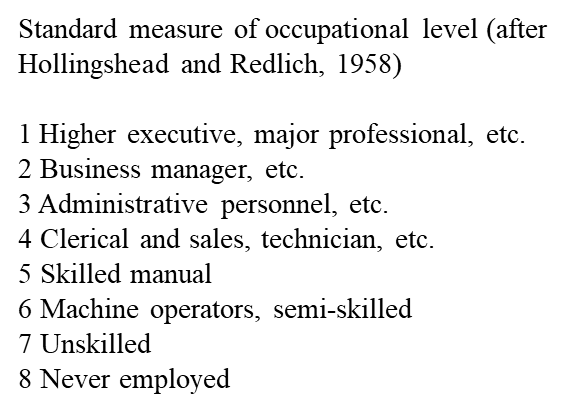

Klein et al. (2012)

How does ADHD impact occupational attainment?

adults (mean age 41) diagnosed with ADHD at 6-12 years of age (vs control), if the occupational level was different depending on if they had ADHD diagnosed as children or not

the smaller the number the higher up in the occupational chain you are, the occupational level was lower for those with ADHD, they were lower in the occupational ladder too and earned less

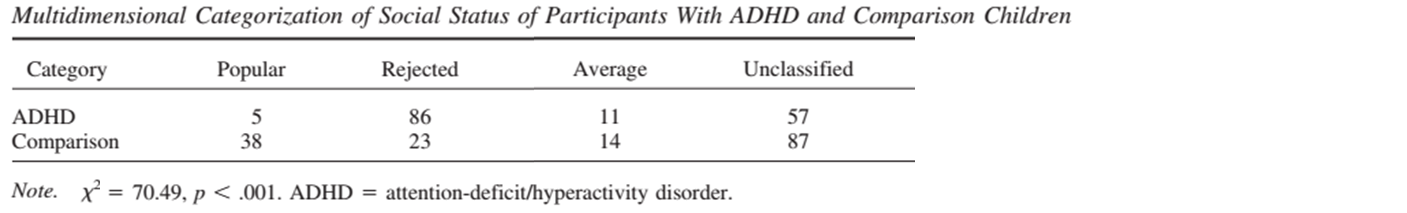

Hoza et al. (2005)

How does ADHD impact peer relations?

Children with ADHD (7-9.9 years of age) and same sex classmates

Lange et al. (2016)

How does ADHD affect physical health?

accidents over the last 12 months requiring medical treatment in children with ADHD (10.4 years old) and controls)

ADHD Control

23.0% 15.3%

OR for accidents was 1.60

likelihood of being injured is about 1.6% higher for those with ADHD

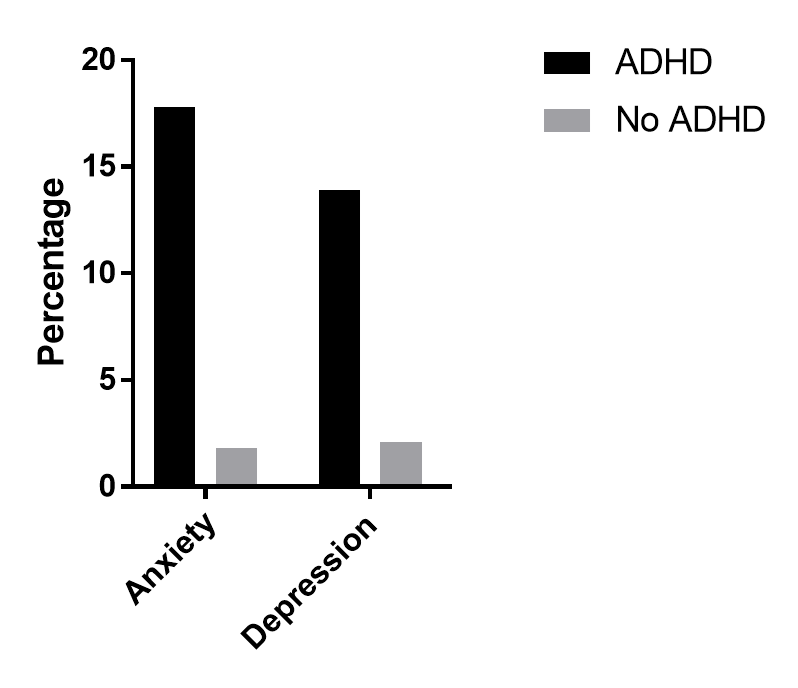

Larson et al., 2010

How does ADHD affect mental health?

children 6-17, 60,000 children, 5000 of which had ADHD

looked at mental health problems in these children

Anxiety and depression are the highest co-morbidity conditions for those with ADHD, but also even ASD and tourettes were more common for those with ADHD

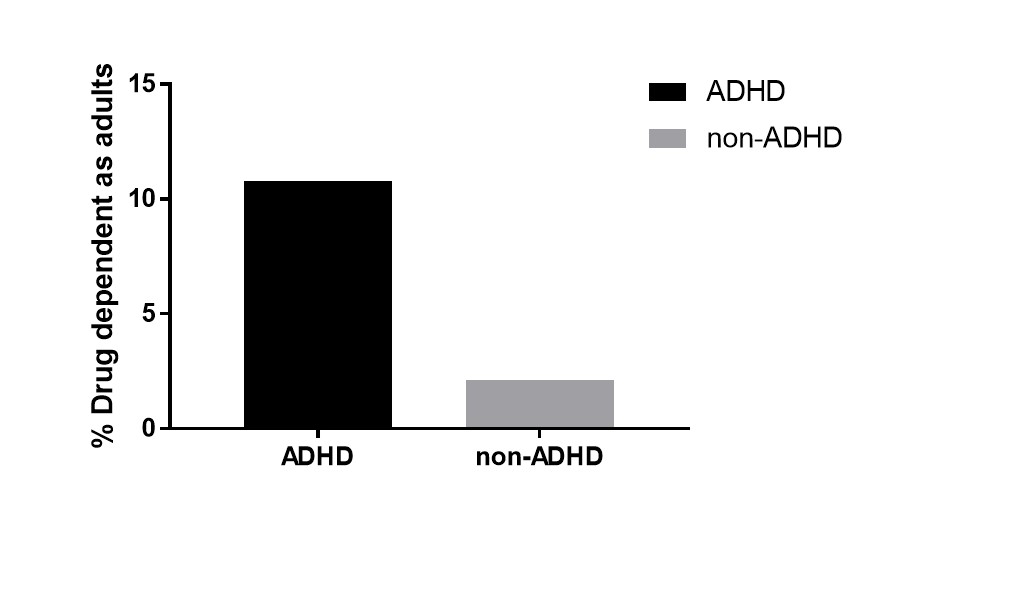

Levy et al., 2014

How does ADHD affect the rate of drug addiction?

their non-alcohol drug dependency for those with ADHD was significantly higher than those without ADHD

looks like if you’re untreated with ADHD, then you’re more likely to develop drug dependency, rather than those treated with drug therapies

First summary

ADHD is characterised by hyperactivity, impulsivity and attentional problems

It affects around ~5% of children/adolescents, and symptoms can continue into adulthood in up to one half of cases

Clinical awareness of the condition dates back to the early years of the 20th century

Term ‘ADHD’ first appeared in the DSM III-R

In general, the condition has a negative effect on:

Academic achievement

Occupational achievement

Social integration

Physical health

Mental health

Classic view 1 regarding the origins of ADHD

it has something to do with the frontal cortex with evidence from neuropsychology, structural imaging, functional imaging

The main neuropsychological evidence is the fact that symptoms of ADHD are similar to the changes following frontal cortex damage

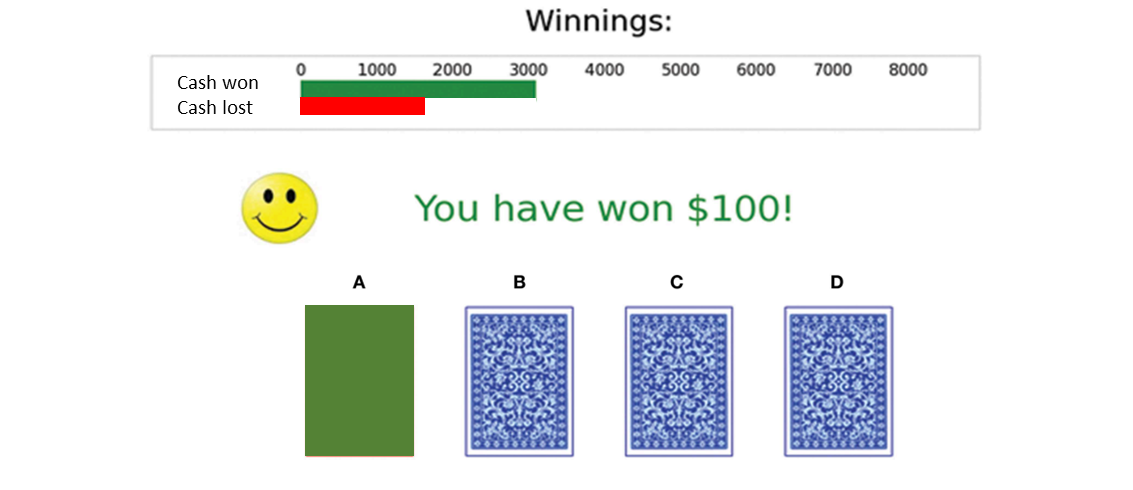

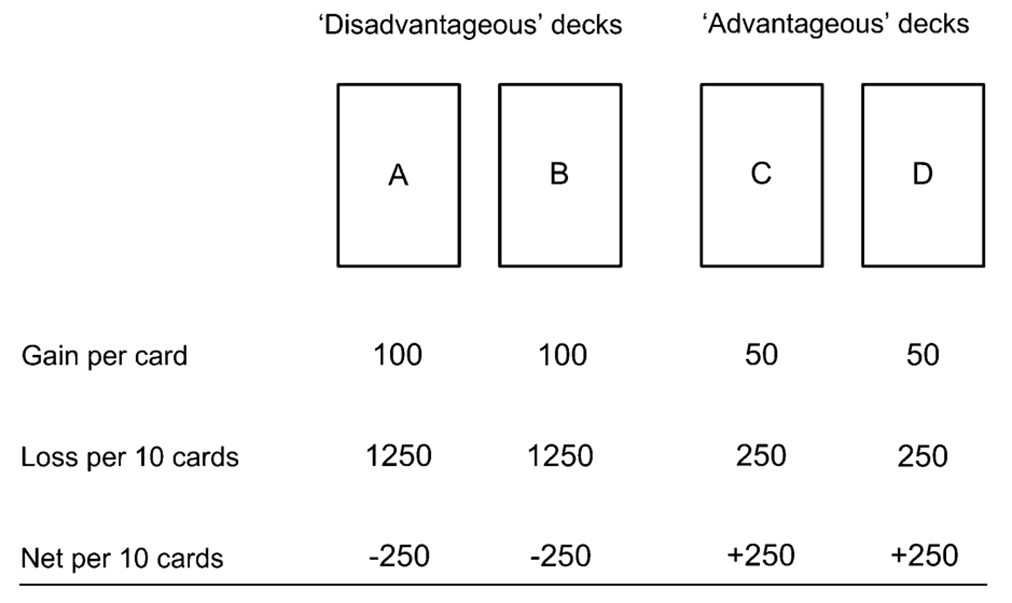

one common consequence of frontal cortex damage is impulsivity, which can be tested in a lab setting by using the IOWA Gambling task

this tests are ability to inhibit gambling actions

looking at the consequences of turning over: if you turn over the ‘advantageous’ decks you gain £50 but lose £5, whereas if you turn over a disadvantageous deck then you gain £100 but lose £125, tests whether the big gain now is good enough to make people continue to gamble even if their odds and the negative consequences of the other decks are worse

people with frontal cortex damage tended to make more disadvantageous choices than advantageous, they were more seduced by the potential big gain you could make in the moment rather than waiting a little longer and gaining less

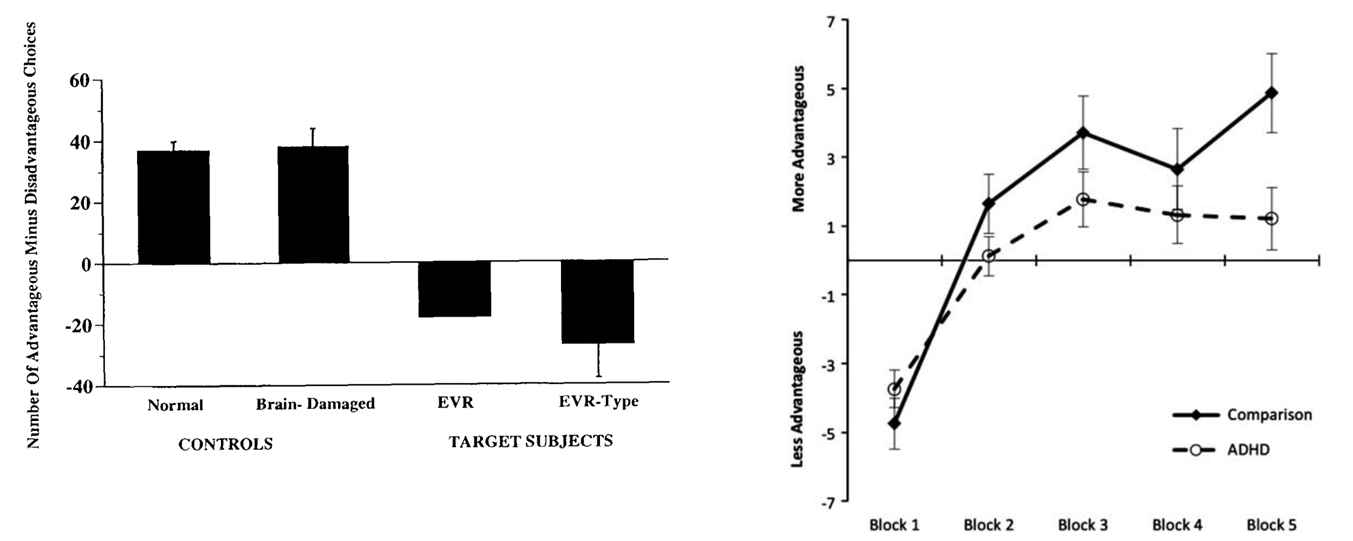

overtime those with ADHD tended to make less advantageous decisions

this distortion of advantageous processing is referred to a ‘delay aversion’ (need the reward now rather than in the future)

Led to Barkley’s ‘behavioural disinhibition’ theory of ADHD (executive)

Russell A. Barkley - Professor of Psychiatry at the Medical University of South Carolina

Sees poor behavioural inhibition as the central deficiency in ADHD

Accounts for attentional and kinetic symptoms

‘Self-control’

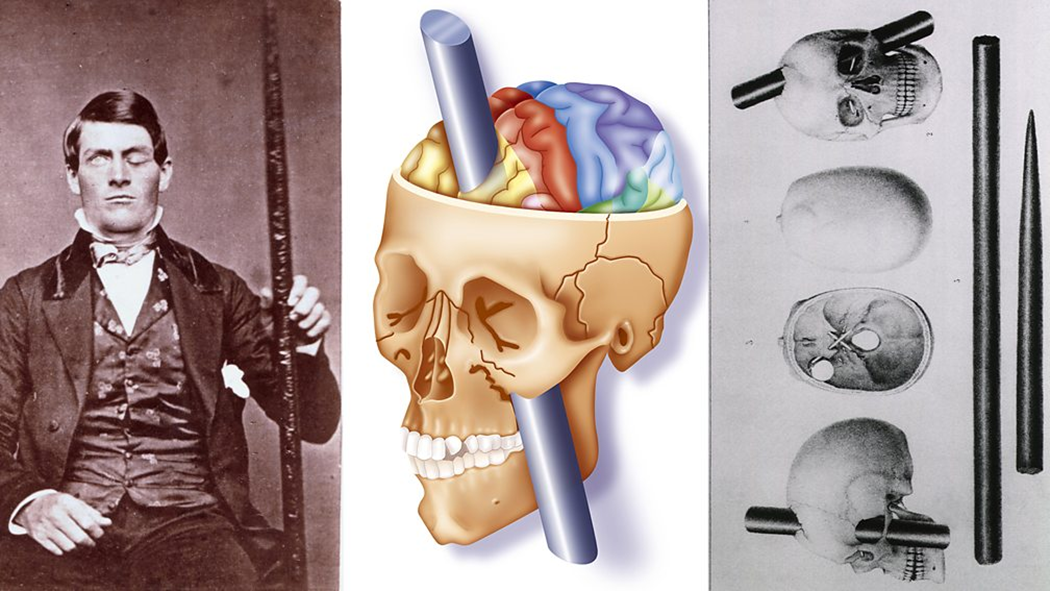

Disinhibited behaviour following frontal cortex damage: classic case

“He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice….” [Harlow]

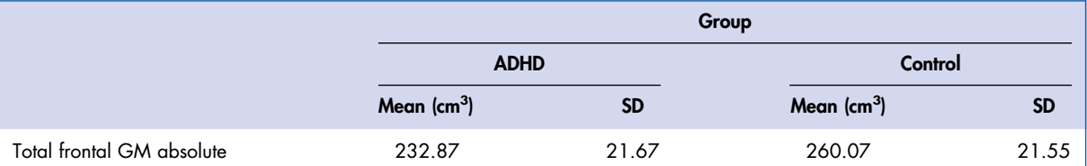

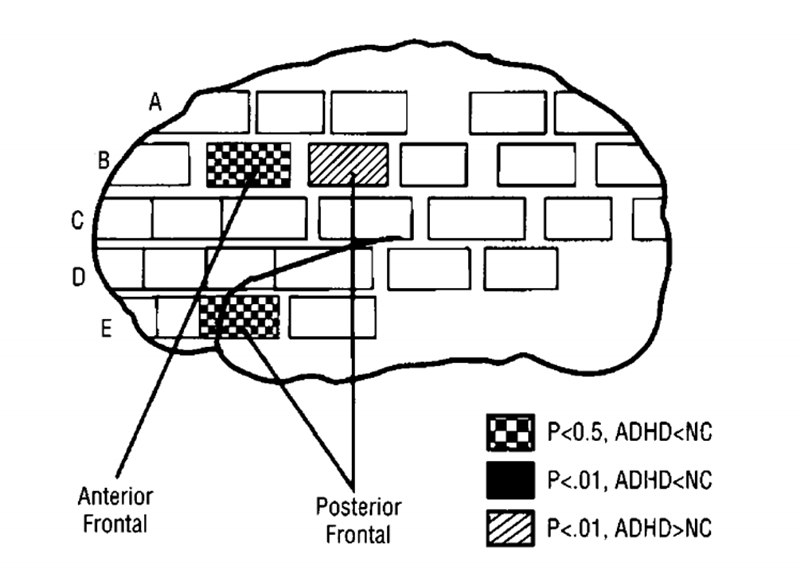

Evidence that ADHD has something to do with the frontal cortex: structural MRI

frontal lobe grey matter volume is lower…

12 kids with ADHD, mean age is 12

mean average of frontal GM amount is much less for those with ADHD

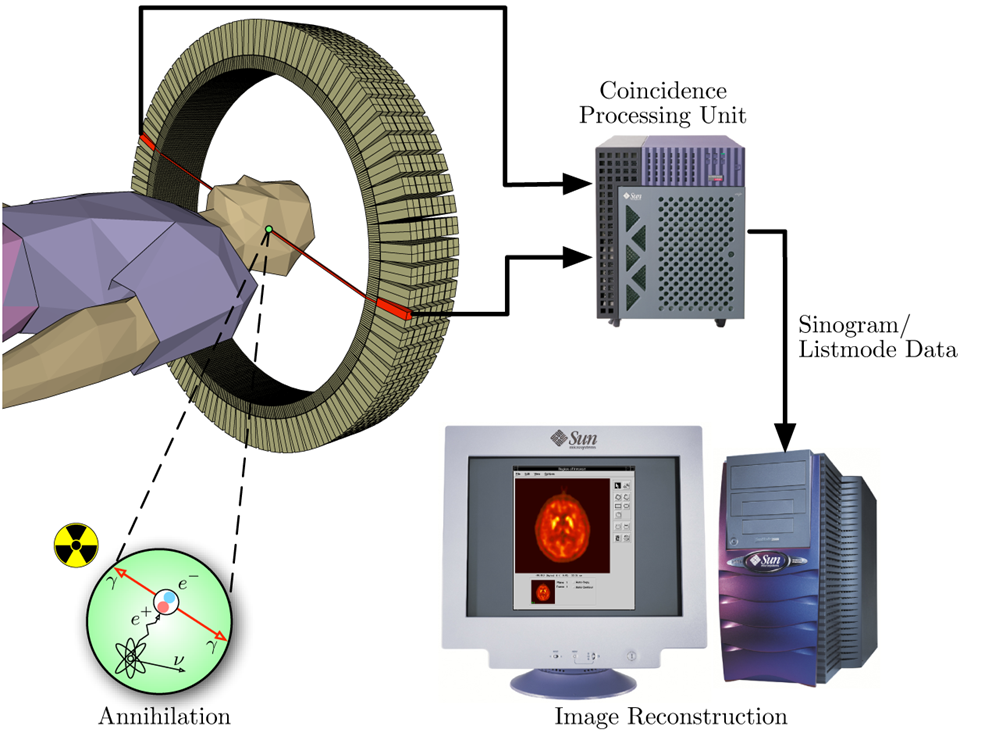

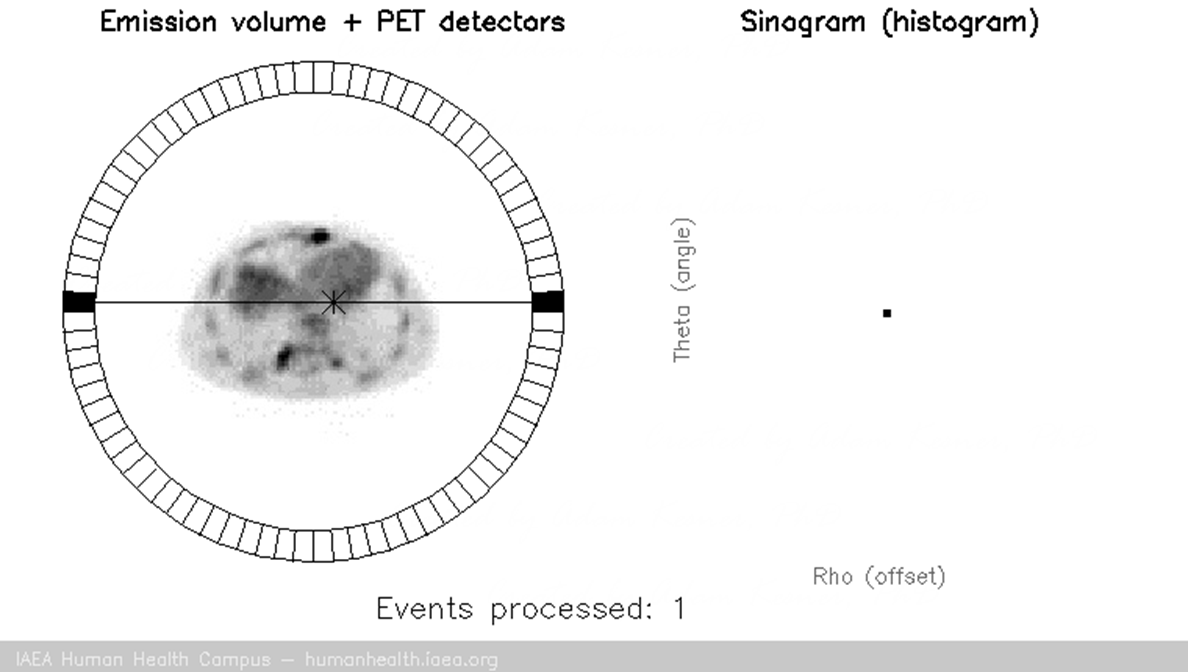

Evidence that it has something to do with frontal cortex damage: functional (PET)

also evidence that the GM left is also less functional, it is hypofunctional

A substance put in the blood can be detected in the brain

depending on which part of the brain is active, it will receive a larger amount of blood than other areas, thus more of the substance

regions of the brain had significantly different rates of glucose metabolism in patients (teenagers with ADHD) compared with controls

areas of the frontal cortex that were less active in ADHDs than in controls is in a chequered pattern, thus those with ADHD had less active frontal cortex

how many people are prescribed methylphenidate per year in the UK?

922,200

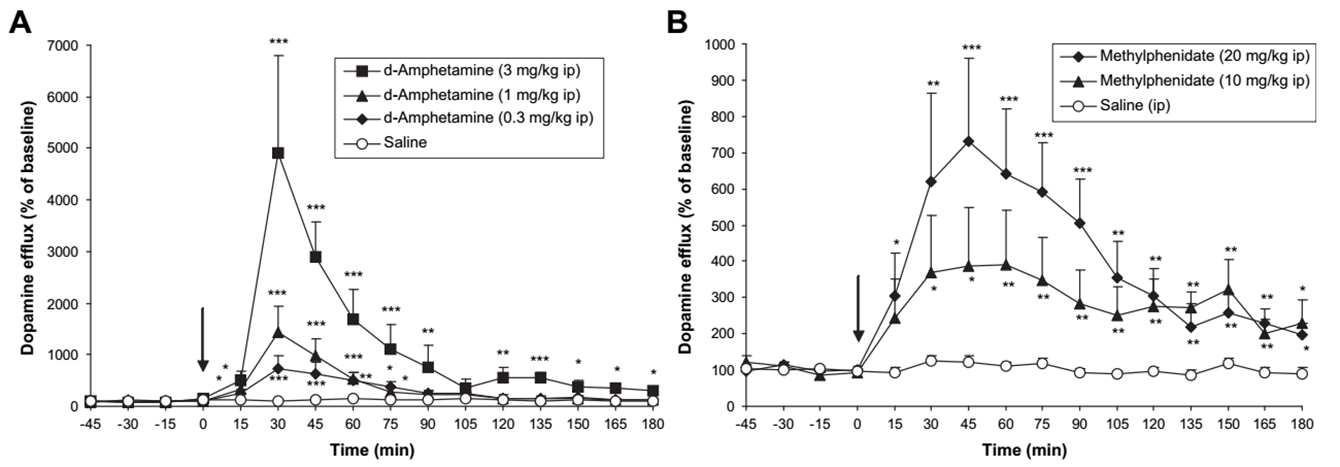

classical theory 2 regarding the potential relationship between dopamine and ADHD

It has something to do with dopamine, as supported by medication, imaging, reward/ reinforcement

evidence 1: Drugs used to treat ADHD increase dopamine levels

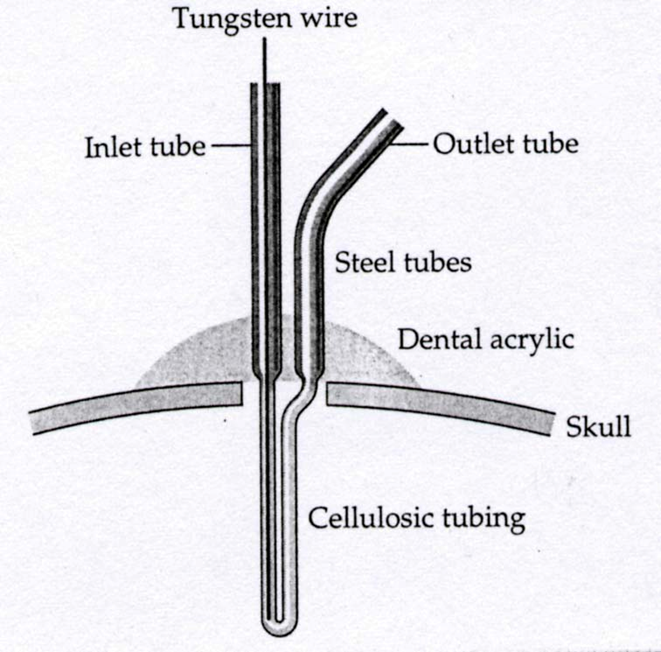

microdialysis:

A small, semi-permeable probe is inserted into a specific brain site

Fluid is supplied through a probe and chemicals in the extracellular fluid diffuse across the membrane and are collected

Samples are then analyzed using chromatography methods (e.g. HPLC)

dopamine levels in the striatum after i.. D-amphetamine or methylphenidate

ADHD is associated with an increase in dopamine reuptake

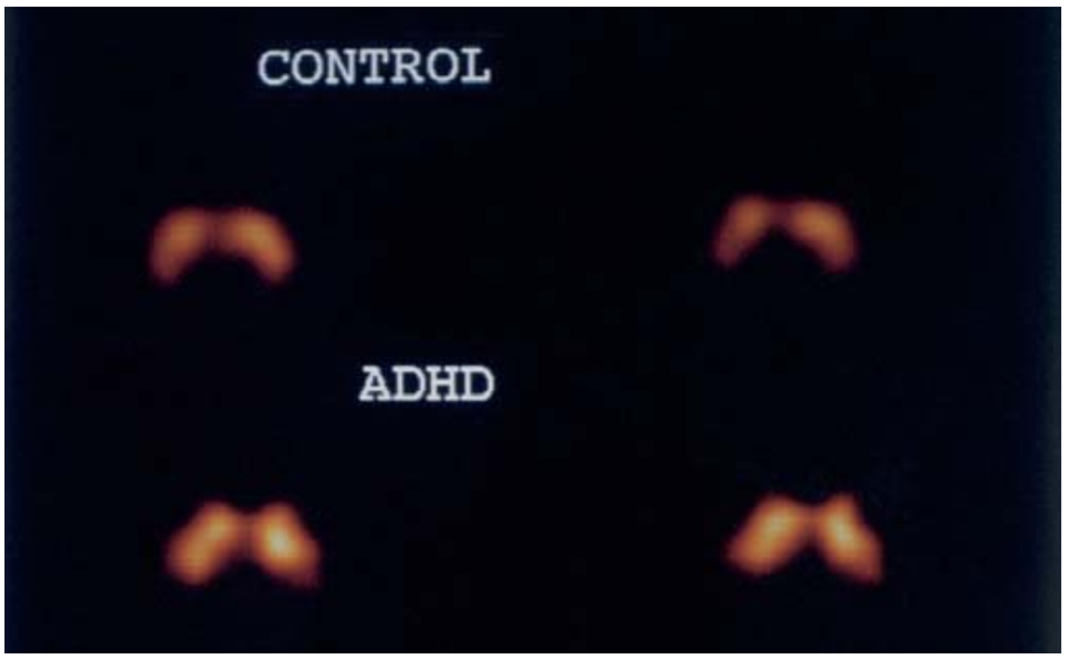

PET

SPECT; a lot cheaper, produces GAMMA rays directly, no need to figure out where within the brain is active, they use a GAMMA camera that pinpoints the area a lot more simplistically

the brighter the image, the more transporters of dopamine the tissue contains, the blobs are the striata which is a large part of the dopaminergic transmission/ neural pathways, because there’s more transporters, the less dopamine you have floating in the brain to be transmitted, the more it is reuptaken by the presynapse potentially, so the levels of dopamine must be lower for those with ADHD than the controls

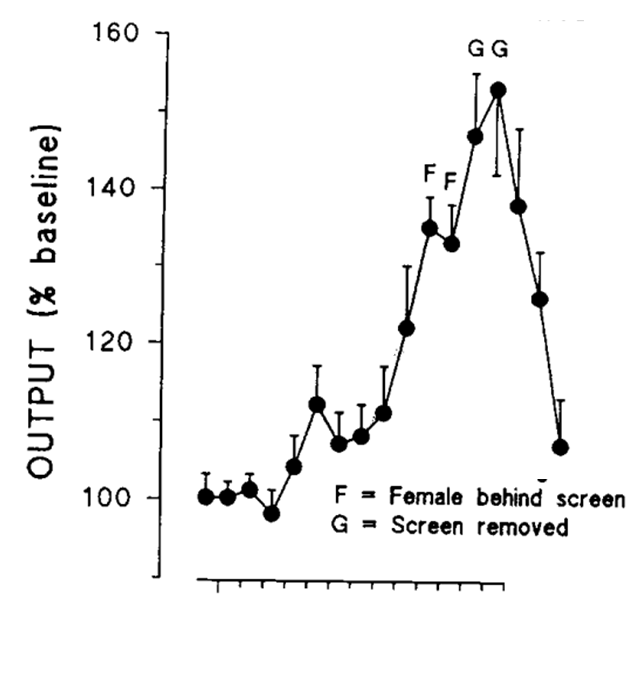

How does rewards have something to do with ADHD? Douglas and Perry (1983)

Evidence for dopamine relating to ADHD

dopamine and the reward of sex

the male and female rats are separated, but there is a massive increase in dopamine levels once the male rat finally sees the female rat

we would expect this to go wrong if this was someone with ADHD

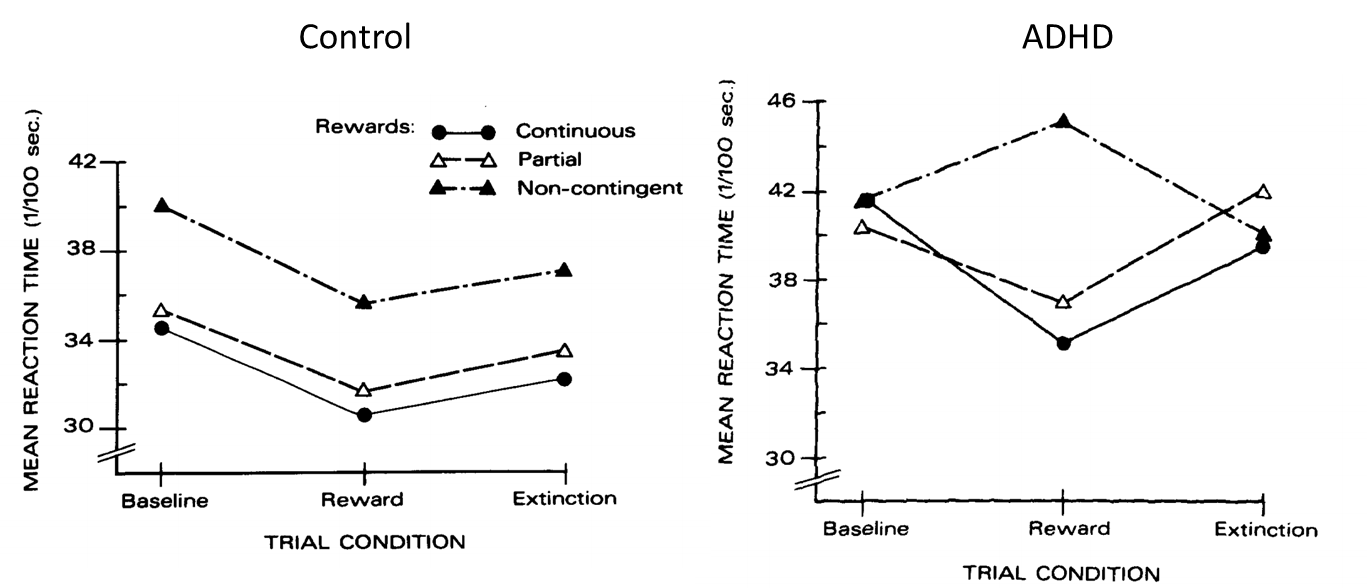

Douglas and Paryy (1983)

Disruption of learning by non-contingent reinforcement

66 elementary school children (mean age 9.5 years old)

33 with ADHD, 33 without

Had to release a response key when a stimulus light came on (reaction time task)

3 conditions: rewarded on every trial when they got faster; rewarded on every other trial when they got faster; rewarded randomly (non-contingent)

Reward = “very good”, “excellent” or “very fast”

Non-contingent reinforcement schedule resulted in slower mean reaction times in the ADHD sample (also delay aversion)

Thus classical theories of ADHD suggest:

1. That the disorder has something to do with the frontal cortex

2. That the disorder has something to do with dopamine

In the case of the frontal cortex, evidence comes from:

Neuropsychology; imaging (structural and functional)

In the case of dopamine, evidence comes from:

Medication; imaging (SPECT); reward/reinforcement

Reading introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by developmentally inappropriate and impairing inattention, motor hyperactivity, and impulsivity, with difficulties often continuing into adulthood.

Definitions of ADHD- DSM-4 Vs DSM-5 Vs ICD-10 and categorical Vs dimensional approaches

hyperkinetic disorder as defined in the ICD:

This includes a more severely affected group of individuals,

as prevalence of hyperkinetic disorder is lower than DSM-IV ADHD.

does not distinguish subtypes; symptoms need to be present from the 3 domains of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity for hyperkinetic disorder.

DSM-IV:

distinguished between inattentive, hyperactive–impulsive, and combined subtypes of ADHD;

DSM-5:

has longer symptom descriptors than DSM-IV.

ADHD subtypes are not stable across time

DSM-5 de-emphasised their distinctions.

DSM-5 has changed the age of onset from before 7 (ICD-10 and DSM-IV) to before age 12.

All 3:

requires the presence of symptoms across more than one setting and requires symptoms to result in impairment, like in academic, social, or occupational functioning.

For clinical purposes, defining ADHD categorically is useful as clinical decisions tend to be categorical in nature.

Categorical decisions on resource allocation, treatment, and ICD-defined or DSM-defined diagnosis provides a reliable way of balancing the risks and benefits of giving an individual a diagnostic label and providing treatments.

However, in terms of causes and outcomes, ADHD is a continuously distributed risk dimension. Individuals with subthreshold symptoms are at risk of adverse outcomes.

Epidemiology- prevalence

The general estimated prevalence of ADHD in children is 3·4% with lower rates of 1·4% for hyperkinetic disorder from European studies.

Prevalence does not vary by geographical location but is affected by heterogeneity in assessment methods (eg, use of an additional informant to the parent or carer) and diagnostic conventions (eg, ICD vs DSM).

has the amount of people with ADHD increased overtime?

Studies in the 20th -21st centuries show no evidence of a rise in rates of ADHD diagnosis across the past decade. There is no evidence of rising population rates of ADHD explained by social change, however, there has been a rise in prescriptions issued for ADHD pharmacological treatment across HICs.

Rises in clinic incidence and treatment could simply indicate increased parent and teacher awareness of ADHD or changes in the impact of symptoms on children’s functioning, or both. Nevertheless, the administrative prevalence is lower than the population figure, highlighting that there is still underdiagnosis.

However, in the USA, studies show geographical variation in patterns of underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis or in ADHD medication prescribing. Highlighting the potential for misdiagnosis and inappropriate use of pharmacological interventions if safeguards are not in place.

These safeguards include ensuring full, good-quality clinical assessments are undertaken, and adherence to national and international treatment guidelines.

female: male ratio of ADHD

Although the male: female ratio of 3–4:1 recorded in epidemiological samples is increased in clinic populations to around 7–8:1, suggesting referral bias to female patients with ADHD. The same is seen for other neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, and communication disorders.

ADHD and age

Core defining features of ADHD tend to decline with age, although inattentive features are more likely to persist. However, the developmental trajectories of ADHD are highly variable.

Around 65% of patients continue to meet full criteria or achieve partial remission by adulthood. Epidemiological studies of the prevalence of ADHD in adulthood are lacking, but one meta-analysis yielded a prevalence of 2·5%.

DSM-5 explicitly allows for symptom decline and requires a reduced number of symptoms for diagnosis of adult ADHD.

There is evidence that ADHD is not simply a problem that most children grow out of. However, transitioning from child to adult mental health clinics is difficult because of a lack of adult services.

Key diagnostic symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: inattentive symptoms

Does not give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes

Has difficulty sustaining attention on tasks or play activities

Does not seem to listen when directly spoken to

Does not follow through on instructions and does not finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace

Has trouble organising tasks or activities

Avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that need sustained mental eff ort

Loses things needed for tasks or activities

Easily distracted

Forgetful in daily activities

Key diagnostic symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: hyperactivity or impulsivity symptoms

Fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat

Leaves seat in situations when staying seated is expected

Runs about or climbs when not appropriate (may present as feelings of restlessness in adolescents or adults)

Unable to play or undertake leisure activities quietly

“On the go”, acting as if “driven by a motor”

Talks excessively

Blurts out answers before a question has been finished

Has difficulty waiting his or her turn

Interrupts or intrudes on others

Early comorbidity

ADHD shows high concurrent comorbidity with other neurodevelopmental disorders—

autism spectrum disorder,

communication and specific learning or motor disorders,

intellectual disability,

tic disorders.

Rates of comorbidity are higher in individuals clinically referred than those who are not referred.

ADHD also shows high concurrent comorbidity with behavioural problems

oppositional defiant disorder

conduct disorders.

Conduct disorder is a risk marker for greater neurocognitive impairment and worse prognosis in children with ADHD. This subgroup of children with hyperkinetic conduct disorder is distinguished in ICD-10 but not in DSM-5.

risk factors: genetics: potential origins

ADHD’s relative risk is 5–9x in first-degree relatives. Twin studies show high heritability estimates of 76%, similar to Sz and autism.

SNPs and CNVs are associated with ADHD risk. Common DNA sequence variants called SNPs are associated, but only when 1000s of SNPs are combined into a composite genetic risk score. Subtle chromosomal mutations, like rare deletions and duplications (CNV), are also associated with ADHD risk; larger effect sizes but uncommon.

Single dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic candidate genes were significantly associated with ADHD. However, psychiatric candidate gene studies of DNA variants in single genes tend to have false positives.

ADHD-associated genomic variants are non-specific; composite genetic risk scores show significant overlap with those contributing to Sz and mood disorders.

ADHD-associated CNVs show overlap with schizophrenia, autism, and intellectual disability. Testing for rare CNVs is not recommended for ADHD.

Most cases of ADHD are multifactorial in origin, but there are rare genetic syndromes (such as fragile X syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, 22q11 microdeletion, and WS) characterised by high rates of ADHD/ADHD-like features. These syndromes are associated with high risk of other disorders, like autism (especially in fragile X syndrome and tuberous sclerosis) and Sz (22q11 microdeletion syndrome).

environment and G-E interplay- prenatal and perinatal factors

Observational case-control and epidemiological studies show that exposures to prenatal and perinatal factors:

environmental toxins,

dietary factors,

psychosocial factors are associated with ADHD.

If causal, manipulation of the risk factor can alter the outcome. However exposures to risks can be affected by unmeasured confounders, selection factors, and reverse causation, where the phenotype influences the environmental exposure.

The prenatal and perinatal factors include:

low birthweight and prematurity,

in-utero exposure to maternal stress, cigarette smoking, alcohol, prescribed drugs, and illicit substances.

For prenatal smoking and stress, the association with off spring ADHD is explained by unmeasured confounding factors.

Environmental toxins:

in-utero or early childhood exposure to lead,

organophosphate pesticides,

polychlorinated biphenyls, are risk factors.

Nutritional deficiencies or surpluses, and low or high IgG food do not to precede ADHD.

Psychosocial risks, such as:

low income,

family adversity,

harsh parenting

are correlates not proven causes of ADHD.

Environment and G-E interplay: adoption

Longitudinal studies, treatment trials, and a study of children adopted away at birth suggest that observed negative mother–child relationships (even in unrelated mothers) arise as a consequence of early child ADHD symptoms (reverse causation) and improve with treatment.

However, exposure to severe, early social deprivation seems to be causal. After being adopted in the UK, Romanian orphans raised in institutions and exposed to early privation in the first year of life showed increased rates of ADHD-like features, cognitive difficulties, and quasi-autistic features into adolescence.

Psychosocial context may shape ADHD presentations and alter developmental trajectories, outcomes, and impairments.

Environment and G-E interplay- genetic liability

Important environmental risks for ADHD and its outcomes may be brought about as a consequence of genetic propensities (gene–environmental correlation).

The effect of environmental factors on clinical phenotype may also depend on genetic liability. For example, animal studies show that environment can alter behaviour depending on the variant of gene carried (G-E interaction).

Effects of gene–environment interplay are subsumed in twin heritability estimates.

Finally, there is evidence that environmental exposures result in changes in brain structure, function, and altered DNA methylation (epigenetics).

ADHD pathophysiology- biology

The biological mechanisms are not understood and there remains no diagnostic neurobiological marker.

The validity of animal models are limited by our incomplete understanding of its pathophysiology in man and how well inattention, motor overactivity, and impulsive responses in tasks in non-human species represent ADHD.

However, animal models have suggested involvement of dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission (in line with the neurochemical effects of ADHD medications) as well as serotonergic neurotransmission.

pathophysiology- cognition

Although there is no cognitive profile that defines ADHD, deficits in neuropsychological domains have been identified.

executive functioning:

the most consistent associations are seen for response

inhibition,

vigilance,

working memory,

planning.

In terms of non-executive deficits:

associations are seen with

timing,

storage aspects of memory,

reaction time variability,

decision making.

However, there is substantial heterogeneity in cognitive functioning, and there is not a straightforward association between cognitive performance and the trajectory of clinical symptoms.

Some cognitive deficits are improved by methylphenidate:

improvements in…

executive and non-executive memory,

reaction time,

reaction time variability,

response inhibition.

Imaging

fMRI studies have found abnormalities in the function of neural networks during cognitive tasks.

Alterations in networks related to attention and executive function as well as alterations in the basal ganglia and limbic areas were found.

Diffusion MRI studies investigating white matter microstructure reported widespread alterations.

Reduced total grey matter and altered basal ganglia volumes seem to index familial risk of ADHD. This suggests that the pathophysiology of ADHD involves abnormal interactions between large-scale brain networks.

Interpretation is complex.

Longitudinal data of the trajectory of cortical development suggest the brain shows maturational delay, with persistence of ADHD indexed by progressive divergence from the normal trajectory. It is unknown whether this phenomenon can be extrapolated to other metrics of structure, microstructure, and function.

The effect of pharmacological treatment is also a consideration as some evidence suggests it normalises macrostructure and function.

Nonetheless, longitudinal studies of adults with childhood ADHD show grey and white matter abnormalities persist to adulthood.

Clinical assessment: what is needed and what to screen for

History taking should not be reductionist— a detailed developmental and medical history and an assessment of family processes and social circumstances.

Check if symptoms can be explained by other difficulties eg, hearing difficulties presenting as inattention.

Information should be obtained from multiple informants. Structured interviews may be valuable, especially if they do not require extensive training.

To decide which individuals need referral to a specialist assessment service use standardised ADHD questionnaires.

ADHD symptoms are commonly associated with neurobehavioural difficulties, which could be comorbid features but should be considered differential diagnoses as treatment is different.

Mental health symptoms to screen for include ODD, CD, anxiety, and mood disturbance. Developmental problems such as reading disorders, developmental coordination disorder, and tic disorders are common.

Because ADHD and ASC co-occur, autistic symptomatology should be considered. ADHD is associated with intellectual disability and emotion dysregulation symptoms (eg, irritability), which can complicate the presentation of symptoms. It is rare to find an individual with so-called uncomplicated ADHD.

A formulation should capture the full range of developmental, behavioural, and psychiatric difficulties. Neuropsychological testing does not have a role in diagnosis of ADHD because cognitive processes are not a defining characteristic. However, cognitive comorbidities like learning disability or dyslexia should be considered.

Summary of the clinical assessment process for children

obtain detailed clinical history from carers and young person

Carry out core ADHD symptom enquiry: are symptoms out of child's age and developmental stage?

Obtain information across settings; consider questionnaires as an adjunct

Screen for associated difficulties (eg, mental health symptoms, other neurodevelopmental or learning problems)

Developmental history (eg, motor delay), Medical history (eg, epilepsy) important in relation to cardiac or other risk factors if pharmacological treatment is being considered, Family history

Consider severity of symptoms, effects on functioning, comorbid symptoms and the family and child's strengths, resources, demands, and psychosocial context when deciding on treatment options

Physical assessment:

signs of other disorders (eg, dysmorphic features, skin lesions) and motor coordination (eg, handwriting, balance)

to be undertaken more completely if considering pharmacological treatment

Baseline height, weight, blood pressure, pulse

Treatment guidelines

Guidelines for the management of ADHD are developed by

NICE and SIGN in the UK,

the Eunethydis European ADHD Guidelines Group (EAGG) in Europe,

the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in the USA.

The main difference is that US guidance does not prevent pharmacological treatment for preschool children or those with mild ADHD; which is not recommended in Europe where a stepwise approach is recommended.

If pharmacological treatment is prescribed, it should be with behavioural interventions—like parental psychoeducation, and behavioural management techniques.

Individual influences on treatment and core interventions

Individual circumstances such as current academic or employment demands and medical history should be considered, and appropriate evidence-based treatments for comorbidities should be initiated.

The only nonpharmacological interventions that currently form a core part of treatment guidelines are behavioural interventions. Initial results from the multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD (MTA), suggested that the combination of intensive behavioural treatment and pharmacological treatment did not offer benefit over pharmacological treatment alone for core ADHD symptoms, but might provided benefit of associated symptoms, levels of functioning and the need for a lower drug dose.

However, there is a beneficial effect of behavioural interventions on parenting and child conduct problems, and that CBT may be useful for adults with ADHD when used with pharmacological treatment.

Stimulants like methylphenidate and dexamfetamine are the first-line pharmacological treatments for ADHD, and the noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine is the second-line treatment.

efficacy of stimulants for ADHD, what psychostimulants are there and what to check for before giving a patient stimulants:

Stimluants increase catecholamine availability.

Although it is recommended that ADHD is treated in individuals with ASD and/or intellectual disability, side-effects of pharmacological treatment in these individuals are more common than in those with ADHD alone.

Meta-analyses have shown beneficial effects of atomoxetine in children and adults. Extended release guanfacine and extended-release clonidine are licensed in the USA. Pretreatment checks, including medical and family medical history (particularly cardiac disorders), are important if medication is taken.

Height, weight, blood pressure, and pulse should be checked at baseline before starting treatment, and compared with normative data. Routine ECG before pharmacological treatment, at the treating clinician’s discretion, could be considered; accounting for medical history, family medical history, and physical examination findings.

Start with a low dose, titrate up according to response, and monitor side-effects. There is no evidence that pharmacological treatment for ADHD is associated with changes in QT interval, sudden cardiac death, acute myocardial infarction, or stroke.

Once treatment is successful…

Once an optimum response is achieved, height, weight, and growth need regular monitoring.

NICE guidance recommends that height is measured every 6 months in young people;

weight is measured 3 months and 6 months after initiation of treatment and every 6 months thereafter in children, young people, and adults;

height and weight in children and young people should be plotted on a centile chart.

Blood pressure and pulse should also be plotted before and after each change in dose and every 3 months.

side-effects include

appetite suppression

Stunted growth ,

which can be off set by ‘stimulant holidays’ when symptom control is deemed less crucial, like weekends and holidays, and by adjusting the timing of doses.

Other side-effects of stimulants and atomoxetine include

gastrointestinal symptoms,

cardiac problems,

insomnia,

tics (less common with atomoxetine).

Prognosis, adverse symptoms and ADHD in prison

ADHD behaves dimensionally: there is no distinct threshold where adverse outcomes appear. A diagnosis of ADHD is associated with premature cessation of education, and poor educational outcomes also extend to individuals with subthreshold symptoms.

A long-term follow-up study showed that childhood ADHD (participants 6–12 years) is associated with adverse occupational, economic, and social outcomes, antisocial personality disorder, and risk of substance use disorders, psychiatric hospital admissions, incarcerations, and mortality. There is increased mortality in adult life in those with ADHD, mainly a result of accidents, and especially with comorbid ODD, CD, and substance misuse.

A meta-analysis of ADHD in prison inmates showed an estimated prevalence of 30·1% in youth prison populations and 26·2% in adult populations, with the risk for female prisoners nearly as high as male prisoners and both have high psychiatric comorbidity. Pharmacological treatment might reduce criminal behaviour and trauma-related visits to emergency departments.

Evidence between ADHD and later unipolar depression is inconsistent; may be because depression is more common in female patients who are under-represented in samples.

future research, clinical directions and issues

Not diagnosing ADHD in the presence of ASC or intellectual disability was a barrier to research. Referral and treatment pathways and service provision tend to be diagnostically focused (ie, autism only), although some services focus more broadly on childhood neurodevelopmental disorders, which is supported by research.

For aetiological and outcome research, we could view ADHD dimensionally but we’re unsure on what dimensions best capture ADHD and how they should be measured—eg, reported symptoms, cognitive tests, brain imaging markers etc. We need to understand the clinical and biological meaning of findings if they affect our understanding and treatment of ADHD.

Treatment of parent ADHD may affect child ADHD features and comorbidity- There is evidence that treating parent depression seems to improve off spring mental health.

Another issue is that genetic and environmental risk factors that cause ADHD are not necessarily the same ones that alter the later course of the disorder or contribute to adverse outcomes. What is needed is research that tests which environmental risks modify the longitudinal course of ADHD across time with designs that control for unmeasured confounders (eg, twin studies) and related parents (eg, adoption studies). This could inform interventions that optimise outcomes.

Another issue is that treatment begins after a child has begun failing across domains. In ADHD the most presenting features can change with age and development. ADHD creates risks of its own and secondary mental health problems commonly arise in mid-childhood and after puberty. How ADHD is best managed across key transition periods (eg, school entry, transition to adult services, and transition to parenthood) needs much more investigation.

conclusions

Although ADHD is viewed with scepticism by some and remains stigmatised by the media, the evidence for it being a clinically and biologically meaningful entity is robust.

There are established assessment methods and good treatment evidence. However, repeated assessment is to be needed and treatment will need adjustments over time.

Impairments beyond core diagnostic criteria, developmental change, and an individual’s psychosocial strengths, weaknesses, and resources are all important aspects for consideration