Chem302 Unit 1 - Physical And Chemical Equilibria

1/35

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

36 Terms

Combustion Reactions

Exothermic, ∆H (-)

Hydrocarbon + Oxygen → Carbon Dioxide + Water

Entropy, ∆Ssys, is (+) when…

phase changes from solid→liquid→gas

num moles increases left to right

mixing or dissolving substances

molecule size or complexity generally increases

system at higher temp

system disorder (num microstates) increases

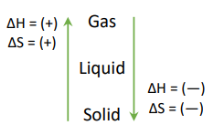

Phase Changes: ∆H and ∆S

∆H (-) for making IMFS, (+) for breaking IMFS

∆S freedom of movement

SIGNS FOR ∆G and ∆S NEED TO BE THE SAME FOR PHASE CHANGES

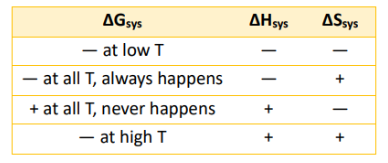

Temp Dependence of ∆G

Given ∆G = ∆H - T∆S

Transition Temp

Phase Transition Temperature from Gibb’s Free Energy Equation

Tphase = ∆H/∆S

Vapor Pressure Theory

VP surface phenomena

IMF inversely related to VP

VP independent of volume bc pressure is collisions with container

Clausius Clapeyron Equation and Theory

ln(P2/P1) = (∆Hvap/R)/(1/T1 - 1/T2)

as T increases, VP increases exponentially

∆Hvap is always positive

as IMF increases, ∆Hvap increases, causing VP to decrease exponentially

as IMF increases, the slope increases on the graph (line becomes steeper)

∆Hvap values for common compounds

H2O: 40 kJ/mol

HOCH2CH2OH: 60 kJ/mol

Hexane: 30 kJ/mol

He: 2 kJ/mol

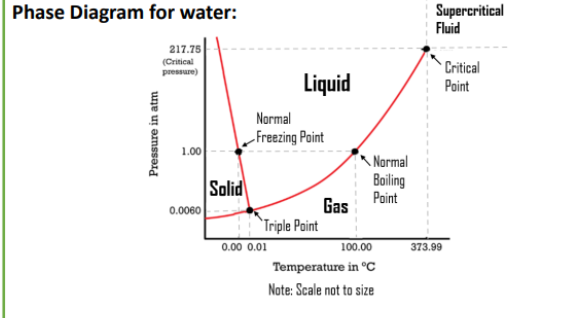

Phase Diagram Interpretation

lines denote the split between phases - crossing a line indicates a phase change

temperature on the horizontal axis, pressure on the vertical

critical point: set pressure and temperature above which the liquid and gas phases meld together to form a supercritical fluid

Phase Diagram for Water

WATER IS UNIQUE

negative slope for the solid-liquid line which indicates solid water is less dense than liquid water

Calculating ∆H across Phase Transitions

Solid Warming: q = mCsolid∆T

Solid Melting: q = m∆Hfus

Liquid Warming: q = mCliq∆T

Liquid Vaporizing: q = m∆Hvap

Gas Warming: q = mCgas∆T

Values to calculate Q across Phase Transitions for Water

Cice = 2 J/g°C

∆Hfus = 340 J/g

Cwater = 4 J/g°C

∆Hvap = 2260 J/g

Csteam = 2 J/g°C

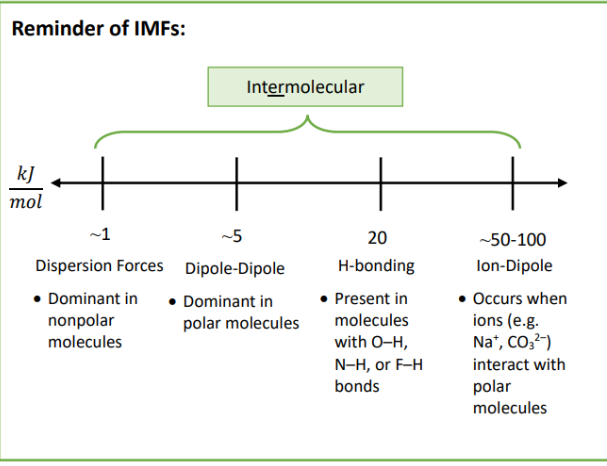

Polar Molecules

Permanent Dipoles

H-bonding

Asymmetrical

Typically polar functional groups (∆EN is large)

ie. -OH, -C-OH, -N-H

Non-Polar Molecules

Dispersion forces

Symmetrical

Hydrocarbons/Lots of alkyl (-CHx) groups

No permanent dipole or hydrogen bonding

ie. -CH2CH2CH3, SF6, O2

Miscibility

Means “mix with”

“Like dissolves like”

Non-polar mix with non-polar, but not with polar or with salts

Polar mix with polar and salts but not hydrocarbons

Molecules with polar and non-polar regions exist (origin of soaps)

Salt Dissociation in Water

∆Gsoln = ∆Hsoln - T∆Ssoln

if ∆Gsoln is (-), salt will dissolve

∆Hsoln can either be (+) [ie, NaCl] or (-) [ie, CaO]

∆Ssoln usually (+) bc dissolving = solid → aqueous, increasing microstates

∆Hsoln for Salt Dissociation

∆Hsoln = ∆HC.L. + ∆Hhyd

plug ∆Hsoln into ∆G equation

∆HC.L.defines energy needed to break bonds in crystal lattice (ALWAYS +)

∆Hhyd (∆Hsolvation) is amount of energy released upon forming solute-solvent IMFs (ALWAYS -)

determines at what temperature the salt dissociates at

Gas Interactions with Water

Reaction: compound has chemical rxn with water

KNOW THESE REACT: CO2 (H2CO3), NO2 (HNO3), SO3 (H2SO4)

Like Dissolves Like: Polar gases dissolve readily

Inert, non-polar gases:

∆Ssoln = (-) bc gas → liquid

∆Hsoln = (-) for gas—water bc IMF is forming

Since ∆S and ∆H both (-), ∆G (-) at low T

gas more likely to dissolve as temp decreases

Henry’s Law

As pressure of gas above a liquid solvent increase, the solubility of the gas in that solven tincreases proportionally.

Pgas increases as Solubilitygas increases

Vapor Pressure in a Binary System

Ptot = PA + PB

where Py = P°Xy

where P° is the pure vaor pressure of the compound

where Xy = (mol y)/(mol total) is the mole fraction

Common Applications of Vapor Pressure Lowering (Colligative Properties)

Resins and plasticizers can be used to reduce the evaporation rate of inks, films, and adhesives

Common Applications of Freezing Point Depression (Colligative Properties)

Salts are added to roads in the winter to thaw the ice

Salt is added when making ice cream to lower the freexing point

Antifreeze (ethylene glycol in water) prevents the colling system in cars from freexing in colder climates

Common Applications of Boiling Point Elevation (Colligative Properties)

Antifreeze ALSO increases boiling point, which mean that a radiator won’t boil on a really hot day.

Common Applications of Osmotic Pressure Differences (Colligative Properties)

Solvent in dilute solutions will move towards more concentrated solutions

Cells lyse (break open) when exposed to distilled (pure) water

Freshwater fish cannot survive in salt water

Calculation for Osmotic Pressure Change (Colligative Properties)

Π = iMRT

Π = osmotic pressure

i = van’t Hoff factor

M = molarity (mols solute)/(L solution)

T = temp in Kelvin

Calculation for Freezing Point Depression/Boiling Point Elevation (Colligative Properties)

∆Tf = i • kf • m OR ∆Tb = i • kb • m

∆Tf/b = change in freezing/boiling point from pure solvent

i = van’t Hoff factor

kf/b = freezing/boiling point constant

m = molality (mols solute)/(kg solvent)

van’t Hoff factor

essentially how many different pieces of a substance exist in solution

Covalent Compounds:

compounds won’t break when dumped into water, so i = 1

Ionic Compounds:

assuming soluble, will break when dumped into water, so i = num ions

ie. NaCl, Na+ and Cl-, so i = 2

Law of Mass Action

Reaction: aA + bB → cC + dD

Equilibrium Constant:

Kc = ([C]c[D]d) / ([A]a[B]b)

Kp = {(PC)c(PD)d} / {(PA)a(PB)b}

Exceptions:

gases can be pressure or concentration but not both

aqueous solutions of mixtures written as concentrations with [ ] symbols

pure liquids and solids ahve a constant concentration which is absorbed into K and NOT included when writing Q or K

Reaction Direction from Q and K

Q = [right]/[left]

if Q < K, rxn shifts right

if Q > K, rxn shifts left

RICE Table

Reaction → write out reaction

Initial Concentration → write the corresponding initial concentrations in the table; pure liquids and solids have no concentration; compounds for which values aren’t given are assumedto be 0

Change → write the change of the compounds in terms of one variable, x

Equilibrium → find equilibrium values in terms of x

insert the equilibrium values into K equation and solve

Le Chatelier’s Principle and Reaction Direction

A system at equilibrium can be stressed by changing temp, pressure or concentration applied to the system.

System can shift to make more on the right or make more on the left.

Direction determined by whichever way reduces stress

Le Chatelier’s Principle: Concentration Stress

aA + bB → cC + dD

add A or B → rxn shift right to ↓ compound

add C or D → rxn shift left to ↓ compound

remove A or B → rxn shift left to ↑ compound

remove C or D → rxn shift right to ↑ compound

Le Chatelier’s Principle: Pressure Stress

pressure only affects gases

↑ in pressure → sys shift to ↓ gas mols

↓ in pressure → sys shift to ↑ gas mols

if ∆n positive

P↑ or V↓ → shift left

P↓ or V↑ → shift right

if ∆n negative

P↑ or V↓ → shift right

P↓ or V↑ → shift left

if ∆n = 0 → no shift due to P/V changes

Le Chatelier’s Principle: Temperature Stress

can easily add/remove heat from sys.

shifts away from heat/cold depending on exothermic/endothermic

Generally:

endothermic: right if heat(+), left if heat(-)

exothermic: right if heat(-), left if heat(+)

van’t Hoff Equation

ln(K2/K1) = ∆Hrxn/R (1/T1 - 1/T2)

∆Hrxn sign inverts depending on which way you write the rxn

rxn exothermic, shift right when T is lower (K2 < K1)

rxn is endothermic, shift right when T is higher (K2 > K1)

Relationship of ∆G° to K

∆G° = -RTlnK

a large negative ∆G° results in rxn shifting far to the right to completion; K with a large positive exponent

a large positive ∆G° results in system staying on the left; K with a large negative exponent