Forensic Psych Final

1/64

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

65 Terms

Types of Prevention

primary = takes place before a crime has occurred to prevent initial perpetration or victimization

e.g. education, training, community-based initiatives, policy and structural change

secondary = immediate responses after a crime has occurred to deal with short-term consequences OR targeting people who are at risk (of victimization, perpetration)

e.g. prevent behaviour from reoccurring or worsening

tertiary = long-term responses after a crime has occurred to deal with long-term consequences

e.g. long-term support for victims, rehabilitation programs for perpetrators

Historically, majority of focus has been on:

secondary and tertiary prevention

focus on supporting victims after the fact

focus on rehabilitative programs after commission of crime

Why focus on secondary and tertiary prevention?

Immediate and visible outcomes are prioritized, aligning with voter preferences and political pressures, whereas primary prevention offers slower, less tangible results.

Secondary and tertiary prevention align with the existing reactive nature of the criminal justice system, while primary prevention fits a public health model that requires broader systemic change.

Public belief in deterrence and demand for tough-on-crime policies drive focus toward strategies that punish or manage crime after it occurs.

Emphasis on individual responsibility frames crime as a moral issue, limiting support for primary prevention approaches that address societal or structural causes.

Why should we focus on primary prevention?

Primary prevention stops harm before it happens, reducing victimization and long-term consequences.

It addresses root causes of crime, such as poverty, inequality, and lack of education, rather than just symptoms.

Breaking the cycle of violence and crime creates safer communities and long-term positive outcomes.

Proactive strategies are more cost-effective over time, compared to the high expenses of reactive criminal justice responses.

Public Perceptions of Prevention Efforts

Public support is crucial for investing in prevention efforts, as buy-in influences policy and funding decisions.

There is strong support for both survivor support and perpetrator accountability, especially in cases of violence or sexual abuse.

Support for prevention depends on public beliefs about the causes of crime and whether certain crimes are seen as preventable.

Perceptions of responsibility matter—people are more likely to support prevention if they see it as a collective duty rather than solely an individual's responsibility.

Primary Prevention: Public Perception = Social Norms Theory

People are heavily influenced by their perceptions of what others believe and do = not whether these perceptions are accurate

People have a conditional preference for complying with social norms

People operate under a set of perceived expectations for proper behaviour

Social Norms Theory: misperceptions of norms

pluralistic ignorance = the majority falsely believes themselves to be the minority

false consensus = the minority falsely believes themselves to be the majority

Social Norms Theory: misperceptions and bystanders = Perkins 2019

Most middle and high school students personally supported reporting weapons to authorities, but believed their peers would not.

Students' own support was strongly linked to their perception of peer support for reporting.

Social Norms Theory: misperceptions and bystanders = Fabiano 2003

Male undergrads underestimated their peers’ values around consent and willingness to intervene in sexual violence.

Perceived peer willingness to intervene was the strongest predictor of their own willingness to act.

Social Norms Theory: misperceptions and bystanders = Stein 2007

Male students overestimated friends' rape-supportive attitudes and underestimated their friends’ prevention efforts.

Their own willingness to prevent sexual assault was shaped more by peer perceptions than personal attitudes.

Social Norms Theory: misperceptions and perpetration

Individuals who engage in IPV tend to overestimate how common IPV is among others, compared to non-perpetrators (Neighbors et al., 2010; Witte et al., 2017).

These misperceptions can influence future behaviour, reinforcing harmful actions.

Belief that peers accept rape myths increases one's own risk of perpetration over time (Loh et al., 2005).

Lower perceived peer support for dating violence is linked to reduced likelihood of future perpetration (Duran et al., 2018).

Social norms are a ________ of behavior and therefore useful for _________ mobilization efforts

power driver

faming

The goal of prevention efforts using the social norms approach is to

correct the “norming of the negative”

these efforts should target bystanders and potential perpetrators of violence

Steps to address the bystander effect

noticing a problematic situation

recognizing the situation as problematic and intervention appropriate

taking responsibility to address it

assessing one’s ability to intervene

choosing to take action

none of this can happen if we don’t perceive a behaviour as problematic OR if we believe the majority do not view the behaviour as problematic

How do we address bystander effect?

Early, age-appropriate education on social norms—like anti-bullying interventions—can reduce harmful behaviours and attitudes while increasing support for reporting (Perkins et al., 2011).

Prevention efforts should include meaningful, intersectional conversations with adults about consent, sexual assault, and accurate social norms, beyond simplistic messaging.

Limitations of bystander effect training

Limited long-term impact: Improves attitudes short-term, but little evidence of lasting behavior change.

Contextual barriers: Fear, uncertainty, and social pressure can still prevent intervention.

Individual focus: Places responsibility on individuals rather than the community.

Overlooks perpetration prevention and often ignores covert forms of violence.

Programs are often male-focused, despite the fact that women can also perpetrate violence.

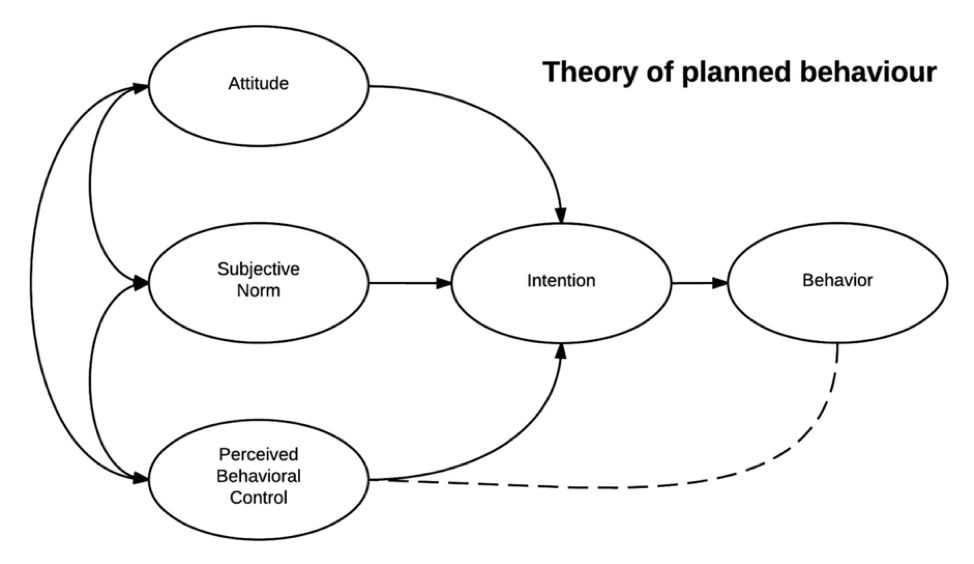

Theory of Planned Behaviour

behaviours and actions are more likely when individuals internalize the following:

attitude = action is likely to be useful or effective

subjective norms = important others (peers, family) believe the action is proper, valued, and expected

perceived behavioural control = a sense of self-efficacy

i.e. the belief that one can skilfully engage in the action

Getting from intention to behaviour

Boost perceived behavioral control by addressing barriers like time, resources, and knowledge gaps.

Make prevention actions easy and accessible through education, skills training, and structural supports.

Support planning and preparedness, helping people map out how they will respond in real situations.

Principles of prevention (what makes an approach effective)

comprehensive = should include multiple intervention components and affect multiple settings to address a range of risk and protective factors

appropriately times = should be targeted at younger populations

uses varied teaching methods = interactive instructions and opportunities for active, skills-based learning

sufficient dosage = longer problems may be more likely to achieve lasting results

administered by well-trained staff = delivered by staff or facilitators that are stable, committed, competent, and can connect effectively with participants

opportunities for positive relationships = foster positive relationships between participants and parents, peers, or other adults are associated with better outcomes

social-culturally relevant = should be sensitive to and reflective of community norms and cultural beliefs

theory-driven = should use established social psychological and behaviour change research to inform program development

include outcome evaluation = should be able to evaluate whether program is meeting pre-defined goals

ideally, programs should have built-in evaluation throughout

Safe Dates

Safe Dates (Foshee et al., 2005) is a school-based program for youth aged 11–17 aimed at preventing dating violence.

It includes nine 50-minute classes and a student-led presentation, focusing on changing norms, improving conflict resolution, promoting help-seeking, and building peer support skills.

Safe Dates Sessions

Defining Caring Relationships

Defining Dating Abuse

Why do People Abuse?

How to Help Friends

Helping Friends

Overcoming Gender Stereotypes

Equal Power Through Communication

How We Feel, How We Deal

Preventing Sexual Assault

Does Safe Dates Work?

The program was evaluated through a randomized trial with a four-year follow-up.

It showed significant reductions in psychological, physical, and sexual dating violence perpetration and victimization, effective for both males and females.

Changes in dating violence norms, gender-role norms, and awareness of community services were key mediators of the program's effects.

Safe Dates for sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth

Wesche et al. (2021) adapted lessons to address the needs of SGM youths, focusing on signs of abuse, barriers to seeking help, and the impact of stereotypes on abuse.

The curriculum included examples of same-gender couples and gender minority partners, and was piloted in 11 US schools and organizations with 156 youths.

Dating violence knowledge significantly increased, with no differences based on gender or SGM status.

Further research with larger, longitudinal samples is needed to confirm findings.

Shifting Boundaries

Shifting Boundaries (Taylor et al., 2012) is a school-based program for youths aged 10-15 aimed at reducing peer and dating violence and sexual harassment.

The program focuses on highlighting the consequences of violent behaviour and increasing faculty surveillance of unsafe school areas.

The goals include increasing awareness of sexual abuse and harassment, promoting pro-social attitudes, encouraging nonviolent bystander behaviours, and reducing dating violence, peer violence, and sexual harassment.

Classroom Curriculum (Shifting Boundaries)

6 sessions

Construction of gender roles

Setting and communicating boundaries in interpersonal relationships

Healthy relationships

The role of bystanders as interveners

consequences of perpetrating

The state and federal laws related to dating violence and sexual harassment

Shifting Boundaries Schoolwide Intervention

Schoolwide intervention included revising school protocols for identifying and responding to dating violence and sexual harassment.

Temporary school-based restraining orders were introduced, along with posters to raise awareness and encourage reporting.

Students mapped "hotspots" of unsafe areas, leading to increased faculty and security presence for better surveillance in those locations.

Does Shifting Boundaries Work?

no significant effect

knowledge of norms, laws, resources

attitudes toward dating violence

sexual harassment perpetration

bystander intentions to intervene

behavioural intentions to avoid perpetration

decreased for intervention group

sexual harassment victimization

total violence victimization

total violence perpetration

later study (Taylor 2015) = effective for both boys and girls

Primary Prevention Child-Focused CSA Programs

Victim-focused CSA prevention programs are school-based and aim to increase children’s knowledge of CSA risks and build self-protective skills, typically for children aged 3-10.

These programs gained popularity due to a rush to address the growing concern of CSA, their ability to reach many children quickly, and their cost-effectiveness.

Alternative approach: Focus should shift to educating parents about creating safe home environments, as they are the most influential in a child’s life (Wurtele, 2009).

Critiques of child-focused CSA programs

Unrealistic expectations: It’s unrealistic to expect young children to defend themselves against complex social, psychological, and physical manipulation, and this expectation isn’t applied to other types of child abuse prevention (Rudolph & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2018).

Challenges in recognizing abuse: Children must identify subtle abusive signals, which is difficult even for adults (Berrick & Gilbert, 1991), and they need to challenge authority figures and report abuse.

Unintended outcomes: These programs can lead to anxiety, fear, over-generalization of "bad touch," and shame or guilt about victimization, not reporting, and confusion about physiological responses.

Primary Prevention: parent-focused CSA programs

Parental involvement in CSA prevention can occur through programs specifically for parents or as part of child-focused programs with parents as adjuncts.

Rationale: Parents influence child behavior, emotional regulation, and communication skills; parent-focused interventions have been successful in other forms of child maltreatment; and parents are often the first to encounter potential CSA due to perpetrators being known to the child.

Effectiveness: Parent-focused programs enhance parent knowledge, attitudes, and communication, but there is no data confirming they reduce CSA overall (Rudolph et al., 2023).

Barriers: Engagement issues (incongruent with family routines), fears and misconceptions (taboo, disbelief, concern about scaring children), and parental discomfort (sexuality, trauma, spousal opposition).

Facilitators: Prior awareness, effective program outreach, and clear communication about the program’s purpose.

Critiques of parent-focused CSA programs

Challenges with parental involvement: Programs require significant parent buy-in, and parents need to be convinced of their usefulness and ability to spot signs of abuse, which is difficult since they are not always present.

Focus on mothers: There is a need for better recruitment of fathers and other family members to be involved in prevention efforts.

Research gaps: More research is needed to determine whether these programs actually reduce CSA victimization.

Potential risk: Parents or family members could also be the perpetrators of abuse, complicating the effectiveness of these programs.

Primary prevention: perpetration-focused CSA programs

High prevalence of child sexual abuse by peers: 50-75% of CSA offenses are committed by other children or youths (Finkelhor et al., 2014; Gerwitz-Meydan & Finkelhor, 2020).

Adolescents are vulnerable: As young adolescents begin to explore sex, they may make poor choices or engage in risky behaviors with younger children, similar to how novice drivers make mistakes.

Lack of sex education: Adolescents are not provided with adequate sex education or the necessary tools to navigate sexual behavior safely, unlike other complex behaviors (e.g., driving).

Program gaps: Most programs focus on peer-to-peer interactions but fail to address older youths offending against younger children, highlighting the need for a public health approach to perpetration prevention in schools (Letourneau et al., 2017).

Responsible behaviour with younger children (RBYC)

Program Overview: Ruzicka et al. (2021) and Letourneau et al. (2024) describe a school-based program for students aged 11-13 years aimed at preventing youth from engaging younger children and peers in inappropriate, harmful, or illegal sexual behavior.

Format: The program consists of 10 interactive 45-minute sessions, including 4 student-led family activities, and can be integrated into the regular health curriculum.

Session Topics: The sessions cover a range of topics including developmental differences, perspective-taking, healthy vs. unhealthy relationships, child sexual abuse facts, prevention strategies, and being a responsible bystander or upstander.

RBYC: preliminary results

Study Overview: Letourneau et al. (2024) involved 160 students in evaluating the effectiveness of the RBYC program.

Findings: The program was associated with increased accuracy in youth knowledge about child sexual abuse, related laws, and behavioral intentions to prevent abuse with younger children and peer sexual harassment.

Limitations: The sample size was small, and no follow-up data is available yet.

Secondary Prevention

early detection and intervention with people at risk/to prevent behaviour increasing in severity

examples of secondary intervention

youth mentorship programs

gang prevention initiatives

community reintegration programs

anti-bullying programs

drug courts and substance use programs

sexual thoughts/behaviour management programs

Secondary prevention is targeted

we need to know who is at risk

how do we figure out whether someone is at risk

examples

youth in homes with abuse/neglect

students displaying aggression at school = indicated by multiple suspensions, detentions, etc.

self-reported risk

substance misuse

Substance use programs as a secondary prevention effort

Substance Use & Crime:

20% of Canadians experience substance use issues in their lifetime.

Substance use increases risk of criminal involvement, especially due to intoxication.

85% of arrested American men tested positive for substances; <25% had outpatient, <30% inpatient treatment.

Treatment Gaps:

Most court-ordered treatments are minimal (e.g., self-help, basic psychoeducation).

Longer treatment (~90 days) is more effective.

Completing treatment linked to better outcomes: more employment, fewer relapses/crimes.

Justice System Integration:

Collaboration between justice and treatment systems can improve rehabilitation and reduce dropout.

Drug courts reduce adult recidivism (50% → 38% in 3 years).

Less impact on youth due to already existing diversion and support structures.

Barriers/Limitations to substance use treatment

Stigma

Comorbid mental health disorders

Finances

Lack of social support

Drop out

Treatment Dropout: ~50% drop out within the first 90 days.

Multiple Attempts: Reaching treatment goals often requires several tries.

Higher Dropout Rates:

Among users of cocaine and methamphetamine.

In longer residential-only programs.

Lower Dropout Rates:

Among users of alcohol and heroin.

In programs combining residential and outpatient services (Lappan et al., 2020).

Critiques or limitations of substance use courts

Lack of Standardization:

Each court operates differently.

Usually limited to non-violent offenders who must plead guilty to participate.

Lack of Evidence-Based Practices:

Most courts do not follow RNR principles.

Treatment is community-based, but lacks quality control or tailoring to individual needs.

Ethical Concerns:

Abstinence-only models dominate, which:

May exclude harm-reduction strategies.

Often restrict access to medications for opioid use disorder.

Are associated with higher mortality rates after treatment.

Recommendations:

The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction recommends collaboration between:

Participants

Community experts

Researchers

→ To improve program effectiveness and ethical integrity.

Secondary prevention of CSA

Recall that two motivators of CSA are

An atypical sexual interest (e.g. sexual attraction to children)

Sexual compulsivity

Current Understanding:

Most knowledge comes from forensic samples (those who have committed contact offences and are known to authorities).

Secondary prevention for CSA has lagged behind initiatives for violence or substance use.

This is due to public perceptions that:

CSA is unpreventable.

Perpetrators are inherently “monsters.”

Focus should be on retribution rather than prevention or treatment (Fix et al., 2023).

Non-Offending Individuals:

Some individuals:

Have never offended.

May have accessed CSEM but not committed contact offences (Bailey et al., 2016; Jahnke et al., 2025).

Many express a desire not to offend, citing:

Concern about legal involvement.

Conflict with personal values.

Awareness of harm caused to victims and their own loved ones.

Introduction of Preventive Programs:

Programs now exist for individuals attracted to children but not criminally involved.

These programs are CBT-based and target dynamic risk factors, including:

Sexualized coping (using sex as a stress response).

Offence-supportive attitudes (justifying or minimizing abuse).

Sexual regulation (managing sexual urges).

Self-efficacy (belief in one's ability to control behavior).

Some programs also offer medications to help reduce sexual arousal.

Where do people attracted to children go for help?

Limited Access to Forensic Services:

Forensic mental health services are typically only available after legal involvement.

Challenges with General Mental Health Services:

Individuals are reluctant to seek help from:

General mental health professionals.

Sex therapists.

Reasons for reluctance include:

Fear of being reported to authorities, even without having offended.

Anticipation of negative reactions or stigma.

Concern that confidentiality won't be respected (Levenson & Grady, 2019).

Fear is Justified:

Research shows that many mental health professionals:

Are unwilling to work with this population—even with no history of offending (Levenson & Grady, 2019; Jahnke et al., 2015).

Feel unqualified or lack expertise (Stephens et al., 2021).

Misunderstand legal and ethical duties, believing they must report even in non-risk situations.

Avoid working with this population due to personal discomfort or moral beliefs (Levenson et al., 2020).

Canada: talking for change

Limitations in Service Delivery = Anonymous treatment is not available in Canada due to legal and ethical restrictions.

Service Availability:

In-person and virtual therapy (individual and group) available in:

Ontario, Atlantic Canada, Quebec, Alberta, Yukon, and Nunavut.

Anonymous chat line provided for:

General questions

Non-judgmental advice

Access to resources and support

Program Structure:

16–20 sessions, including:

Psychoeducation on sexual health and behavior

Exploration of personal values

Work on core beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors

Challenging negative thinking patterns

Development of a coping and healthy living plan

Problem-solving skills

Communication and assertiveness training

Evaluation Status = The program launched in 2021 and is still under evaluation for effectiveness and outcomes.

Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention focuses on reducing reoffending after a crime has occurred, through measures like prison, fines, community sentences, and treatment programs.

While primary and secondary prevention are ideal for crime prevention, tertiary efforts remain critical for managing offenders and reducing recidivism.

Incarceration alone is not effective in reducing reoffending; treatment and skills-building programs are necessary both in prisons and in the community.

Various theories and models guide tertiary prevention strategies to help reintegrate offenders and reduce future crime.

Rehabilitation "theory"

Rehabilitation-based approach: Criminal behavior can be changed by targeting underlying causes through interventions that address cognitive, environmental, and experiential factors.

Crime is learned: Criminal behavior is shaped by experiences and environment, not just genetics, and can be unlearned through effective interventions.

Rehabilitative programs should focus on accountability, addressing risk factors, teaching risk management skills, changing pro-criminal attitudes, and preparing individuals for reintegration into society.

Key components: Programs should include readiness for change, individualized treatment, substance use treatment, education, vocational training, and community re-entry support.

RNR (risk-need-responsivity) model

A framework for assessment and rehabilitation of people involved in the legal system.

RNR has shaped rehabilitation efforts world-wide.

Used in all programs delivered by Correctional Services Canada

RNR - RISK

Higher intensity for higher-risk individuals: Programs should offer more intensive interventions (e.g., more frequent sessions, longer duration) for individuals at higher risk of reoffending.

Risks of treating lower-risk individuals: Providing treatment to lower-risk individuals may inadvertently increase their risk of reoffending by associating them with higher-risk offenders and removing protective factors like stable housing and employment.

Targeting higher-risk individuals reduces recidivism: Focusing interventions on higher-risk individuals has been shown to significantly reduce recidivism compared to targeting lower-risk individuals.

RNR - NEED

Prioritize criminogenic risk factors: Programs should focus on dynamic (changeable) risk factors that contribute to criminal behavior to reduce recidivism.

Impact of targeting dynamic risk factors: Addressing these factors leads to a significant reduction in recidivism, with studies showing a 19% reduction (Bonta & Andrews, 2017).

Target multiple risk factors: Since most individuals have more than one risk factor, programs should target several areas for a higher chance of successful reintegration.

"Central Eight" risk/needs factors: The key factors that should be addressed are: criminal history, pro-criminal attitudes, pro-criminal associates, antisocial personality, employment/education, family/marital issues, substance use, and leisure/recreation.

RNR - Responsivity

Match treatment style to individual needs: The treatment style should align with the justice-involved person’s learning style and abilities.

General responsivity: Programs should be cognitive-behavioral, based on learning principles, and focused on skill acquisition to ensure effectiveness.

Specific responsivity: Programs must be tailored to individuals' motivation, readiness for change, and personal factors like intelligence, age, gender, culture, and language to optimize outcomes.

Adapt staff interactions: The approach of staff should also be matched to the specific needs of the individual, enhancing the effectiveness of the intervention.

Decrease in Recidivism based on

RNR Programming

Good Lives Model (GLM)

Positive, strengths-based approach: The Good Lives Model (GLM), developed by Ward in the early 2000s, focuses on helping individuals achieve primary goods like health, knowledge, autonomy, and relatedness, rooted in positive psychology.

Primary goods vs. secondary goods: Primary goods (e.g., knowledge, inner peace, community connections) are pursued through secondary goods (e.g., education, work). Crime occurs when individuals use criminal means to attain primary goods.

Rehabilitation focus: GLM-based rehabilitation programs help individuals pursue primary goods through prosocial, law-abiding means, creating individualized case plans tailored to achieving specific goals.

Limited evidence: There is a lack of rigorous evidence (e.g., RCTs) on the effectiveness of GLM in reducing recidivism.

The war of 2 models = RNR vs. GLM

Focus & Framework: RNR is deficit-based, targeting criminogenic risks (“Central Eight”) and matching intervention intensity to risk; GLM is strengths-based, helping individuals pursue meaningful “primary goods” through prosocial means.

Evidence & Adoption: RNR boasts 40+ years of empirical support and wide implementation (e.g., Correctional Services Canada); GLM is theoretically appealing but lacks robust RCT evidence on recidivism impact.

Complementary Use: Practitioners often integrate RNR’s risk management with GLM’s life-goals focus—using RNR to assess and mitigate risk, and GLM to build positive, prosocial case plans.

Desistance theory

Desistance is a Process: It refers to the voluntary cessation of criminal behavior and is not a linear process.

Theories of Desistance: Various theories explore why and how individuals stop engaging in criminal behavior over time.

Aging and Criminality: Aging is often seen as a factor in desistance, with individuals typically "growing out" of crime, as reflected in the age-crime curve.

Peak Offending: Criminal behavior tends to peak during the mid-teenage years, supporting the idea of aging influencing the reduction in criminal activity.

Desistance - life stability

Employment is a strong predictor of desistance (Giordano et al., 2002)

Reduced financial stress through a reciprocal exchange of social capital between employee and employer

Limited exposure to criminal opportunity, antisocial peers

Direct informal social control (i.e., social norms, peer expectations)

Development of a sense of identity and meaning to one's life

Stable, healthy relationship (e.g., marriage)

Considered a "turned point" or a significant life event that can lead to desistance

Less time for criminal pursuits

Other factors related to relationship like cohabitation, birth of child - shifting values

Desistance - narrative scripts

Narrative Scripts: These are the personal stories people tell themselves about their identity and role in society.

Condemnation Scripts: Common in individuals who continue engaging in criminal behavior; they often have an external locus of control, blaming factors like poor education or family issues for their actions.

Redemption Scripts: Seen in individuals who desist from crime; they take responsibility for their behavior, have an internal locus of control, and actively seek change to move away from criminality.

desistance - social identity

Constant Risk: Individuals with legal involvement are often seen as perpetual risks, and proving they are reformed takes time.

Primary Desistance: The initial decision to stop engaging in criminal behavior.

Secondary Desistance: The transformation in self-identity and ongoing efforts to maintain desistance.

Identity Shift: Desistance involves distancing from a criminal identity and cultivating positive roles, such as being a responsible parent, a good family member, or a contributing community member.

Community reintegration

Goal of Tertiary Prevention: To reduce the risk of reoffending, especially for those reentering society after incarceration.

Federal Incarceration in Canada: About 75% of federally incarcerated individuals are serving determinate sentences, meaning they have a set release date.

Successful Reintegration: Focus on increasing the chances of successful community reintegration by identifying factors linked to success.

Parole and Reoffending: People released on parole are less likely to reoffend compared to those who are not, even when controlling for risk factors.

When does community reintegration start?

During Incarceration: Institutional programs aim to prepare individuals for reintegration by providing education, mental health care, substance use treatment, job training, and mentoring.

On Parole: Most individuals are released before their warrant expiry date, typically after serving 1/3 or 2/3 of their sentence, and continue to be monitored by Correctional Services Canada (CSC).

After Warrant Expiry: Higher-risk individuals may serve their full sentence before release and are no longer followed by CSC, unless a Long-Term Supervision order is in place.

Potential Challenges Faced upon Community Release

Stigma

Understanding and navigating parole conditions

Poverty

Finding employment

Finding housing

Discrimination by service providers

Continuing to manage mental health, substance use issues

Isolation, acclimating to new community

Lack of social network

Community reintegration - individual factors

Mother-Child Programs: Mothers can apply for programs like MCP to keep their babies with them until around age 2.

Age and Employment: Older individuals tend to have better success in the community, but younger individuals are more likely to secure employment.

Gender: Men are more likely to be rearrested than women, with most programs focusing on male needs. Programs for women are criticized for having a male-centered view of risk and needs in parole (Hannah-Moffat & Innocente, 2013).

Race/Ethnicity: Racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to be rearrested due to over-policing and racial profiling, highlighting unmet needs in reentry programming.

Substance Use and Mental Health: Individuals with substance use or mental health difficulties often face challenges in reentry, with those suffering from serious mental illnesses being more likely to have their community sentences revoked.

community reintegration for people with serious mental illness

Transitional Planning: Mental health treatment upon release is linked to lower re-incarceration rates. Key aspects include ensuring individuals have access to mental health services, sufficient medication, and necessary identification (e.g., health cards).

Community Mental Health Initiative: This initiative provides access to various specialist services (social workers, mental health nurses, etc.), which has been shown to reduce reoffending. However, there is a shortage of mental health professionals willing to work with individuals with complex needs.

Need for Community-Based Treatment Centers: There is a push to develop more centers for people with serious mental illness to help with reintegration, with only one such center currently available in Brockville.

Community Supervision: Individuals on community supervision have case managers or parole officers. Technical violations are more common among those with mental illness, and best practices suggest using alternative sanctions rather than reincarceration, along with problem-solving strategies to improve compliance.

Community reintegration - housing

Stable Housing and Recidivism: Lack of stable housing is linked to higher recidivism rates due to increased stress, exposure to criminal behavior, and decreased access to services, negatively affecting physical and mental health.

CSC Community-Based Residential Facilities: These facilities, also known as "half-way houses," provide housing for individuals on day parole, full parole, or long-term supervision orders. They offer programming like life skills, substance use treatment, employment support, and crisis counseling.

Variety of Residences: Housing options vary based on risk and needs, ranging from 24-hour supervision and programming to minimal intervention. Some facilities are run by non-profit organizations such as the John Howard Society and the Elizabeth Fry Society.

Social Barriers that might be present for people reintegrating from prison?

stigmatization

peer/family support aka social circle

public perceptions toward people who have offended are highly negative and viewed as dangerous, unwilling to change and undeserving of help

worse for certain crimes and visible minorities

causes difficulties for

housing

employment

relationships

safety

success in community

Who might also be impacted by stigma toward past offending?

family

loved ones

friends

secondary stigma

Community reintegration - social barriers

Secondary Stigma: Family members of individuals who have committed serious crimes (e.g., sex offenses, mass killings) experience stigma, often blamed for facilitating the offense or failing to prevent it, a phenomenon known as "secondary stigma."

Kin Contamination & Kin Culpability: There is a societal perception that family members are contaminated by association, and may be held responsible for the offender’s actions, whether due to perceived negligence or direct involvement (e.g., poor parenting or complicity).

Impact on Relationships: Secondary stigma can strain familial relationships, leading to the loss of prosocial connections and further isolating both the offender and their family.

Need for Reentry Programming: Programs are needed to help justice-involved individuals and their families rebuild and maintain relationships, navigate new prosocial connections, and reintegrate successfully into society.

Community reintegration programming for people who have committed sexual offences

circles of support and accountability (CoSA) Canada