Stereotypes & Prejudice (Week 9)

1/48

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

49 Terms

‘Prejudice’

• From the Latin, praejudicium • Prae: ‘in advance’ • Judicium: ‘judgement’ • Has a specific meaning in a legal context • But what psychological concepts does this remind you of?

Schemas

• A mental framework or body of knowledge that organises and synthesises information about something. • These help us interpret people, situations, events, roles, places etc

Schemas and stereotypes •

Once we learn that in certain situations most people act in a specific way, we develop schemas for how we expect people to act in those situations.

• Once we get to know a person, we develop schemas for how we expect them to act across situations.

• If a major part of our perception of an individual concerns their membership of a certain group, then the stereotypes we hold about that group will act as a form of schema, and influence how we expect them to behave.

• This can be relatively benign, or extremely offensive!

So… • We may have certain mental shortcuts, biases or schemas about how we interpret the social world that cause us to ‘pre-judge’ the thoughts, values, attitudes, behaviour, moral character etc of other people – particularly those we see as different to ourselves.

• These shortcuts may be influenced by the stereotypes we hold about certain groups.

• They may lead to discrimination (deliberate or otherwise)

Definitions:

Stereotypes, Prejudice and discrimination

• Stereotype: A simplified but widely shared belief about a characteristic of a group and its members.

• Prejudice: Negative feelings towards persons based on their membership in certain groups.

• Discrimination: Negative treatment of persons because of their membership in a particular group.

Where do stereotypes come from?

• Socialization – Process by which people learn the social norms of their culture or group

– Includes stereotypes, how valued or devalued various groups are, and which prejudices are deemed acceptable

– Learned from parents, teachers, peers, popular media, and one’s culture.

– Children pick up stereotypes by observing and imitating their elders: listening to disparaging group labels or derogatory jokes that elicit approving laughter

Gender stereotypes & Socialisation

• Shaped by the media and cultural norms. • E.g. pink for girls, blue for boys. • However, this is relatively historically recent. Ladies' Home Journal article in June 1918 said, "The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl."

Negative stereotypes, minority groups and cognitive biases

• Negative behaviours can come to be stereotypically associated with minority groups, even if they are no more prevalent among such groups than in the majority group.

• Illusory correlation: An overestimate of the association between two variables that are only slightly, or not at all correlated.

• This is due to a combination of minority group distinctiveness and trait negativity bias

Minority Distinctiveness x trait negativity bias

Hamilton & Gifford (1976)

• Presented participants with information about majority group A, and half as much information about minority group B.

• Ratio of positive: negative information was 2:1 in both cases. • When participants were subsequently asked to attribute negative behaviours to one or the other group, they attributed them to Group B.

• Due to distinctiveness: because both the minority group characteristics and negative information were infrequent, both were distinctive and stood out.

• The negative behaviours then came to be seen as representative of Group B.

Implications?

• Negative information (e.g. crime) about a minority group is more distinctive than negative information about a majority group.

• Over time, we come to see that negative information as representative of that minority group (“they’re all criminals”).

• This is especially the case if information appears to support an already held stereotype: confirmation bias, or if media framing of negative information emphasises minority group membership.

Can explain why young minority men are targeted by police

Stereotype threat

• The experience of concern about being evaluated based on negative stereotypes about one’s group.

• Proposed by Claude Steele in relation to academic/intellectual performance • A form of self-fulfilling prophecy.

• Can be implicit as well as explicit, and unrelated to whether an individual believes the stereotype themselves.

A further critique • ‘Stereotype threat’ seems to place the responsibility for overcoming stereotypes back on structurally disadvantaged/minoritised individuals.

• It could be misread as telling such individuals that their experience of negative stereotypes and discrimination is “all in their head”. • And yet we know discrimination is real! • Shouldn’t the responsibility for dispelling stereotypes lie with institutions and broader society?

How does stereotype threat hamper achievement?

1. Directly – the ‘threat in the air’ may increase anxiety and trigger distracting thoughts.

2. Indirectly- if someone feels their identity isn’t valued or stereotyped in an academic domain, they may disidentify with that domain – dismiss it as irrelevant to their self-esteem and identity.

Stereotypes and institutions: ‘identity fit’

. • Organisational culture of many workplaces: workforce consists of straight, white men. • Enabling diversity in the workplace means ensuring that identifying with being an employee is compatible with salient personal identities.

Self-categorisation

• In identifying the groups we encounter, we build categories around the personal characteristics that members of that group seem to have in common, but also how people within the group seem to be expected to behave and think: the norms of the group.

• This is known as a group prototype.

• If we perceive ourselves as being similar to other members of a group, this will increase our tendency to categorise ourselves as belonging to it, and hence increase our identification with it.

But… what if we are qualified for a certain job in an organisation, but do not see ourselves as being like the other people who carry out that job, and are uncomfortable conforming to the social norms of the organisation?

The importance of ‘fit’

• Women are highly underrepresented in surgery. • Peters et al. (2012) study of surgical trainees found that the stereotypical image of a surgeon was highly masculine.

• Female surgical trainees reported a lack of fit between their own identity and the perceived masculine surgeon stereotype.

• Problem: Field of medicine potentially missing out on excellent surgeons because the ‘macho’ image of Kim Peters surgery alienates women.

How to address this? • Promoting women who have achieved success in stereotypically male dominated fields as role models. • Changes in the social norms of organisations to break down stereotypes and make it clear that a variety of personal identities are welcome.

So… • We may have certain mental shortcuts, biases or schemas about how we interpret the social world that cause us to ‘pre-judge’ the thoughts, values, attitudes, behaviour, moral character etc of other people – particularly those we see as different to ourselves. • These shortcuts may be influenced by the stereotypes we hold about certain groups. • They may lead to discrimination (deliberate or otherwise)

Types of prejudice that can lead to discrimination

• Overt prejudice

• Implicit prejudice

• Structural prejudice

Overt prejudice

blatant, obvious hate feelings towards someone due to their group.

• Apparent rise in ‘hate crimes’ in Ireland in recent years. • Garda policy on ‘hate crimes’ evolving – should allow collection of more accurate statistics.

• Rise in far-right activity targeting migrants over the past three years.

• Current legislation aimed at updating the Prohibition of Incitement to Hatred Act 1989, which predates widespread Internet usage and is seen as not fit for purpose. (However, this has become politically complex).

Studying prejudice

• Allport (1954) The Nature of Prejudice. • Highly influential – the foundational text for the social psychological study of prejudice.

• Defined prejudice as “an antipathy based upon a faulty and inflexible generalisation. It may be directed toward a group as a whole, or towards an individual because he is a member of that group”.

• Locates prejudice as a characteristic of the individual. • This has arguably led social psychology to focus too much on individual prejudice as leading to discrimination, rather than structural discrimination.

• Allport’s definition of ‘prejudice as antipathy’ has been criticised. • Much sexism derives from paternalism rather than antipathy.

• Discrimination can arise from a wish to favour the ingroup rather than hatred of the outgroup.

• Taking 1950s USA as the basis for studying prejudice has arguably led to overgeneralisation: many social psychological studies may not take sufficient account of the nuances of how prejudice operates in other countries that are not the USA.

Is prejudice a personality trait?

• Personality research has investigated why some people appear to display more prejudice and act in a more discriminatory way than others.

• Adorno et al (1950) conducted the Authoritarian Personality studies in the United States in an effort to understand why some people were attracted to anti-Semitic and fascist politics.

• They measured prejudice with a personality test called the F-Scale: for ‘potential for fascism’

• They argued that there was a link between prejudice towards other, ‘weaker’ groups and idealisation of strong authority figures.

Other measures of Authoritarianism Altemeyer– The Right-Wing Authoritarianism Scale (RWA)

Sidanius & Pratto– Social Dominance Orientation (SDO)

– The Right-Wing Authoritarianism Scale (RWA)

• Consists of three characteristics:– Authoritarian submission: a tendency to yield to authority– Authoritarian aggression: a desire to punish those who are ‘different’

– Conventionalism: a desire for adherence to traditional social norms.– Altemeyerhas found that RWAs are more prejudiced towards groups they see as being low-status, or as flouting traditional social values.

Sidanius & Pratto– Social Dominance Orientation (SDO)

• A scale developed to measure strong beliefs in social hierarchies • High scorers on the SDO scale are likely to believe that some groups are naturally superior to others, and to prefer an unequal society that they believe benefits them. Jim Sidanius • Often used in conjunction with the RWA scale

Implicit prejudice

• “Prejudice that operates unconsciously and unintentionally” • Assessed by the Implicit Association Test developed by Anthony Greenwald, Mahzarin Banaji and others.

• Investigates implicit associations between evaluations of certain groups and positive and negative terms through a sorting task. • Available via Moodle

Implicit Prejudice and Behaviour

• Implicit prejudice exists ‘below the surface’; they are prejudices we don’t like to admit we hold – even to ourselves! • They are formed by conditioning: associations between members of certain groups and negative stimuli.

• Most people’s score on the IAT will indicate at least a small implicit bias against outgroups.

• Most evident in spontaneous, unplanned behaviour such as body language.

High IAT scores predict unfriendly nonverbal behaviours in interracial interactions.

• Does have real-world effects: Doctors with high pro-white IAT scores were more likely to prescribe anti-pain medication to white patients than black patients.

• BUT: Does not necessarily translate directly into prejudiced behaviour or discrimination.

Where we have the opportunity to plan our behaviour, we can consciously override our implicit prejudices to ensure we are not acting in a discriminatory fashion.

Criticisms of implicit prejudice theory

• Arguably, the fact that most people will register a score on the IAT indicating some level of prejudice may have the effect of normalising and trivialising prejudice, rather than consciousness-raising.

• Does placing emphasis on implicit prejudice lead us to overlook the role of structural factors/ power relations? • Increasing criticism of the use of implicit bias training by large organisations as a way of displacing the responsibility for discrimination from institutional leadership onto individual employees.

• Implicit/unconscious bias training materials are regularly developed from a questionable evidence base: while they may raise awareness, there is little evidence that they are successful in changing behaviour. • Poorly delivered bias training may result in a backlash.

Racism and cultural norms

• In most contemporary societies, there is a strong injunctive norm against racism and discrimination.

• The majority of people will (publicly) agree that racism and discrimination is wrong, but may disagree on what racism is.

• Treating racism as a personality trait, may lead to an overemphasis on dichotomy of individuals as either ‘racist’ or ‘not racist’ without understanding how racism works in society.

• Individual and institutional behaviours which may not have been discriminatory in intention, may be discriminatory in practice.

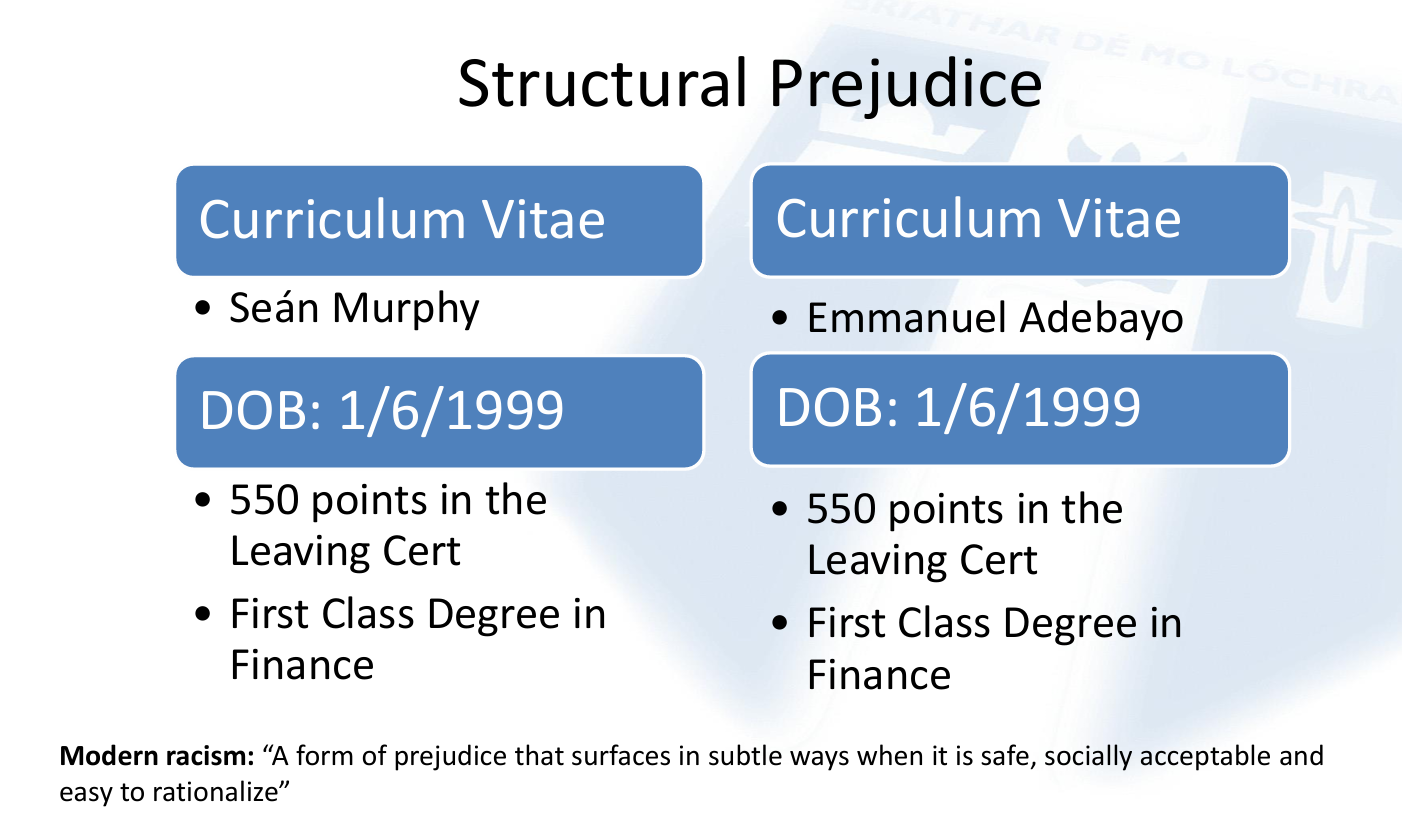

Structural prejudice

McGinnity et al (2009)

• Created matched CVs with names indicative of Irish, German, Asian and African names.

• Sent out applications in response to 240 job ads.

• Found that candidates with Irish names were over twice as likely to be invited to interview for advertised jobs as candidates with identifiably non-Irish names, even though both submitted equivalent CVs.

• Found no difference between German, Asian and African names

• Found no difference by employment sector.

• Evidence for in-group favouritism

Critical social psychology and prejudice

• Social psychology has traditionally studied prejudice on an individual basis – whether as a trait (some people are more prejudiced than others), or as a state (we are all prejudiced sometimes).

• Critical social psychologists (e.g. Mick Billig, Margie Wetherell, Jonathan Potter) argue that it is more appropriate to study prejudice as a social and historical phenomenon, that is reflected in the attitudes, behaviours and language of individuals, rather than something that has its origins in the individual.

• Discursive social psychology takes a particular focus on the techniques people use to rationalize behaviour or attitudes that might be seen as racist.

It is comforting and sometimes crucial to be able to point to moral weaknesses in other members of society. But we need to ask whether racism is solely the province of the inadequate and poorly developed individual.

Rhetorical strategies

Discursive psychological research has identified five rhetorical strategies people use to allow potentially prejudiced arguments to be heard as non-prejudiced (Goodman, 2014)

1. Denial of prejudice “I’m not racist, but…”

2. Grounding of views as reflecting the external world “It’s not racist, it’s common sense. I live in the real world”.

3. Positive self and negative other presentation“We Irish are a generous people, and I think some so-called refugees take advantage of that”

4. . Discursive deracialisation It’s not about prejudice, it’s about resources. We just don’t have houses for everyone”.

5. the Liberal arguments for illiberal ends “It’s important to treat everyone the same: we shouldn’t give anyone special treatment just because they’re from a poor background.”

Investigating prejudice on social media

• Increasing focus on how talk about prejudice and discrimination is negotiated on social media.

• Some researchers focus on the far-right (e.g. Shani Burke’s work on Islamophobic and anti-Semitic Facebook groups), others on ‘mainstream’ discourse.

Shani Burke • Sambaraju (2022) How prominent non-white Irish people are rhetorically included and excluded from the national in-group in Twitter responses

Microaggressions:

Everyday, typically subtle but hurtful forms of discrimination experienced quite frequently by members of minority groups.

Theories of intergroup conflict

• Realistic group conflict theory: Groups will come into conflict in ‘zero-sum’ situations where scarce resources can only be gained by one group at the expense of the other.

• Social identity theory: Group conflict is made more likely by the need to maintain a positive image of the group in relation to other groups.

Solutions to intergroup conflict: The contact hypothesis.

Theory of the Week Direct contact between hostile groups will reduce intergroup prejudice, under certain conditions.

Background to the contact hypothesis

• What happens when two groups meet? • Can they live in harmony, or will they inevitably come into conflict? • For much of the early 20th Century, social scientists believed that intergroup conflict was an inevitable feature of human society. All history is only one long story to this effect: men have struggled for power over their fellow men in order that they might win the joys of earth at the expense of others

Segregation in society

Beliefs that it was better to keep separate ethnic groups apart became increasingly prevalent in the 1920s and 1930s. Black and white toilets

Desegregation

• As American society became increasingly desegregated, US social scientists began to notice some effects. • After the desegregation of the Merchant Marine, the more voyages White sailors took with Black sailors, the more positive their racial attitudes became (Brophy, 1946).

• White police in Philadelphia who had worked with Black colleagues showed fewer objections to taking (Kephart, 1957). orders from a Black officer, than those who had not

• The experience of fighting together with Black soldiers during the Battle of the Bulge sharply changed the attitudes of White American soldiers: southerners as well as northerners (Stouffer et al, 1949)

Conditions

1. Contact must be supported by the authorities, law or custom 2. Contact must occur under conditions of equal social status 3. Contact must involve personal intergroup cooperation 4. Contact must involve the achievement of a common goal.

Friendship?

• Increasing focus on cross-group friendship as a means of reducing prejudice. • Pettigrew (1997): the more friends from minority groups participants had, the less prejudice they showed and the more sympathy and admiration they had for these groups. • Friendship more effective than co worker or neighbour contact

Contact and outgroup homogeneity

• Outgroup homogeneity effect: The tendency to assume that there is greater similarity among members of outgroups than among members of ingroups.

• Arises because we tend to have less personal contact and familiarity with individual outgroup members and we often don’t encounter a representative sample of outgroup members.

• However, contact allows us to see the diversity in the outgroup and also points of similarity with ourselves.

Applications of the contact hypothesis

• Racial desegration in schools. • Post-conflict reconciliation in Northern Ireland, South Africa and Cyprus. • Inclusion of children with SEN in mainstream education. • Reduction of prejudice towards migrant and refugee children in British, German and Italian classrooms

Muzafer Sherif (1906-1988)

• Born in Turkey in 1906 • In early life, lived through Italo-Turkish War, two Balkan Wars, WWI, Greek occupation & Turkish War of Independence.

• Moved to United States in 1926 for postgraduate study completed PhD in Psychology at Columbia University • Returned to Turkey in 1936 – became increasingly politically in opposing pro-Nazi sympathies in (officially neutral) Turkey during WWII. • Was arrested and detained for four weeks in 1944, and left for the USA soon afterwards. • Married Carolyn Wood (another social psychologist) in 1945 – frequently worked together afterwards

Intergroup processes

• Sherif was frustrated by individualist approaches to intergroup processes.

• He argued that to study intergroup processes, it was necessary to take an intergroup approach i.e. look at how groups interacted with each other.

• As a psychologist, he was also interested in the role of the individual within groups – but individuals could not be understood independently of their social context. • This required a specific methodological approach field experiments.

Objectives and definitions

• Sherif wished to examine experimentally how intergroup attitudes and behaviours e.g. prejudice and discrimination, were affected by the nature of intergroup relations.

• Conceptualised groups as being more than just a collection of individuals, but having a nature of their own

• Intergroup relations: ‘functional relationships between two or more groups and their respective members’.

• Needed to study actual interactions– Between individual group members– Between groups as entities

Boys camp studies EXPERIMENT

• Carried out three studies at boys summer camps, investigating relations and interactions between two groups at the camps.

• 1949: Connecticut • 1953: Upstate New York (Sherif viewed this version as a failure and abandoned the experimental aspect before the camp ended).

• 1954: Robbers Cave, Oklahoma Participants • Sought to control for individual differences by ensuring homogeneity of subject as to sociocultural and personal backgrounds.

• 24 White, protestant 12-year-old boys, of ‘normal’ physical and psychological development.

• Screened via school-records, interviews with parents and psychological tests.

• The boys thought they were attending a normal summer camp – unaware of experiment– A degree of informed consent obtained from parents: although Sherif may have been deliberately vague on the details.

The research team • The research team consisted of six men – Sherif himself, along with five of his junior colleauges and graduate students. • They were divided into an operational team (the two youngest men) and a research team (the remaining four). • The operational team acted as the counsellors for the boys – organizing their camp activities etc.

• The research team posed Marvin Sussman, Muzafer Sherif & Herbert Kelman as camp directors and handymen in order to be able to gather observational data on the boys’ behaviour.

Study phases

1. Ingroup formation

2. Intergroup conflict

3. Reduction of intergroup conflict

Phase 1: Ingroup formation • In the first two experiments, the boys attending the camps were split into two groups after the first two days.

• In the Robbers Cave experiment, the boys were split into two groups from the start (the Rattlers and the Eagles), without knowledge of the other group.

• During this phase, the boys were encouraged to engage in collaborative tasks with collective rewards e.g. treasure hunts, building huts, preparing food etc.

• Competitive activities were discouraged.

Phase 1: Formation of Group Norms

• Boys took on roles of leaders and followers.

• Strong behavioural norms emerged within the groups

– Encouraging toughness

– Discouraging the expression of homesickness

Phase 2: Intergroup conflict

• When both groups learned of the presence of the other group, they immediately reacted with suspicion and prejudice.

• This also led to stronger proclamations of group identity – the groups made flags and banners.

• Sherif then brought the groups together to compete in a series of tasks e.g. tug of-war, baseball, singing performances etc.

Intergroup hostilities

• The groups were observed to become more hostile to each other – disparaging each other and trading insults.

• On one occasion, when the Eagles had lost a task, they responded by raiding a Rattler cabin and burning one of their flags.

• Leadership within the groups also changed, as the focus changed from the common good of the ingroup, to beating the outgroup.

– Intergroup competition led to changed intragroup relations

Measuring intergroup attitudes

• The experimenters asked boys from each group to rate boys from their own and the other group on positive (‘brave’, ‘tough’, ‘friendly’) and negative (‘sneaky’, ‘smart alecs’, ‘stinkers’) traits.

(Rattlers rated Rattler raters Eagle raters Eagles rated 4.86 2.08 2.76 4.7)

Phase 3: Reduction of Intergroup Conflict • The experiments first tested whether intergroup contact in the absence of intergroup competition would reduce hostility.

• The groups were brought together for meals, watching movies and other non-competitive activities.

• However, hostilities continued!

Phase 3: superordinate goals

• The experimenters then tested whether negative intergroup attitudes and behaviours would be reduced if the groups had to cooperate to achieve mutually valued superordinate goals, that neither group could achieve alone.

• The boys had to cooperate to– Repair the camp’s water supply– Pool money to watch a movie– Pull the fire truck up a hill– Set up camp

Results of superordinate goals

• Implementation of cooperative tasks saw a gradual reduction in name calling, the use of derogatory terms, hostile expressions and the avoidance of out-group members. • These findings confirmed in intergroup ratings. • The boys also started spontaneously sharing prizes and cheered when they found they could all take the last bus home.

Compare: The contact hypothesis

Direct contact between hostile groups will reduce intergroup prejudice, under certain conditions

Conditions

1. Equal status. Contact must occur under conditions of equal social status

2. Personal Interaction. The contact should involve one-on-one interactions among individual members of the two groups.

3. Cooperative activities. Members of the two groups should join together in an effort to achieve superordinate goals.

4. Social norms. The social norms, defined in part by relevant authorities, should favour intergroup contact.

Lessons from the study

1. Groups matter – they have a reality of their own, including roles and status relationships. • Roles and status will vary according to the nature of intragroup and intergroup relations.

2. Groups have psychological validity for the members – members will identify with the group and adopt the group goals as personal goals.

3. Stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination are psychologically meaningful outcomes of the nature of intergroup relations.

• Intergroup competition for limited resources causes negative intergroup impressions, attitudes and behaviour • Intergroup contact alone is not sufficient to reduce intergroup hostility • Sustained cooperation necessary to achieve mutual goals can help reduce intergroup hostility.

Criticisms

• Validity– There were in fact three groups present, not two. The experimenters (working as camp admin) were also a group the boys would have oriented to.

– The boys may have taken the fact that their aggressive behaviour wasn’t stopped as a sign that sort of behaviour was tolerated/encouraged.

• Lack of certainty about cause and effect

• Ethics– The boys’ parents were not fully briefed about the nature of the camps. They were variously described as being about investigating how best to organize summer camps, or as studies in leadership. – The boys were subject to interpersonal violence and taunting. When interviewed many years later, some of the participants described the lack of adult intervention as unsettling. – They were never fully debriefed. Many only learned years later that their summer camp experience had been a psychology experiment.

Doug Griset (1942-2022)

Doug Griset participated as an 10 year-old in the 1953 camp in upstate New York. The experience ended for him when he was hospitalized due to a stomach injury acquired during a poorly organized baseball game.

‘It’s in retrospect thinking about it that I get angry. What kind of men would be standing there taking notes and pictures of boys as they struggled over a game of tug of war. You know, who are these bastards? I get angry about that part. And then three weeks at 10 years old? Come on, that’s not right. So, no it was not anything done bad to me as far as I know and I really believe that. Yes, it probably made me a better person in the long run or a tougher person or whatever, I’ll buy that. But it wasn’t right. It was the wrong thing to do. He went on to have a successful law career and was a senior judge in New York State. Morally it was the wrong thing to do.’ Interviewed by Gina Perry for her book, ‘The Lost Boys’. Impact: Realistic Group Conflict Theory • Levine & Campbell (1972

Impact: Realistic Group Conflict Theory

• Levine & Campbell (1972) • “Hostility between groups is caused by direct competition for limited resources” • Real-world evidence that hostility towards outgroups rises during times of economic hardship.

Impact: Social Identity Theory

Social identity theory built on Sherif’s observations regarding the importance of group identification, and the need to view the group positively as a basis for group behavior particularly stereotyping and prejudice.

1. Threats to one’s self esteem heighten the need for ingroup favouritism.

2. Expressions of ingroup favouritism enhance one’s self-esteem.

3. A blow to one’s self image evokes prejudice and the expression of prejudice towards an outgroup helps restore self-image.