chromosomes and cytogenetics

1/13

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

14 Terms

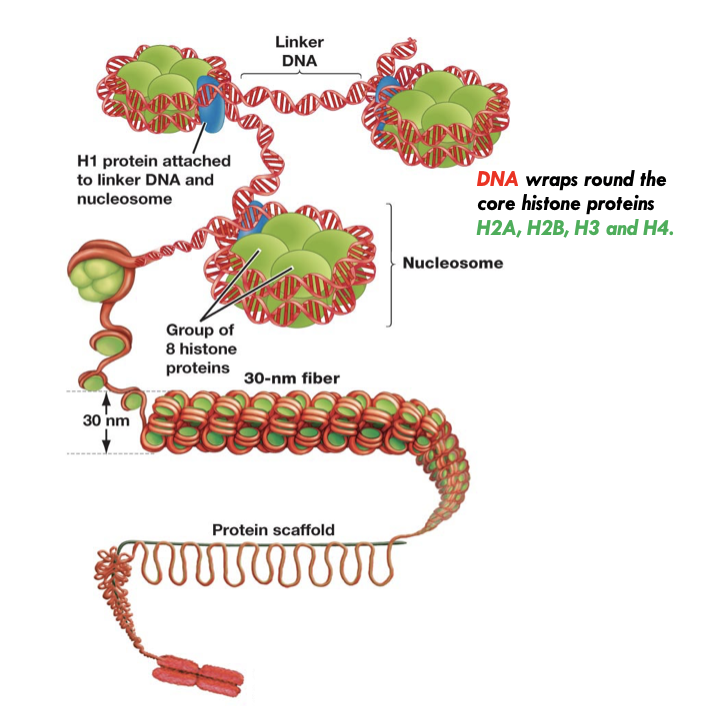

chromatin

In chromosomes, DNA is compacted by forming complexes with histone proteins

Most condense form

Can exist at euchromatin or heterochromatin

Occurs during metaphase

Regulated by interaction with histone proteins

Wraps around twice

Forms a nucleosome

Can form a 30 nm fibre

30 nm fibre loops around a protein scaffold

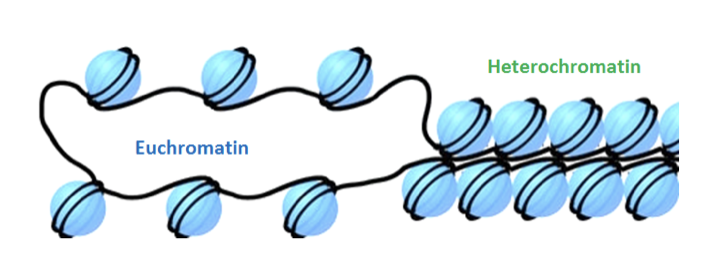

euchromatin

Most of the genome is in the form of 'euchromatin'

The degree of compaction varies and can be very dynamic

Can regulate association with H1, which in turn regulates rate of gene transcription

Contains all of the genes

Forms 90% of chromosomes

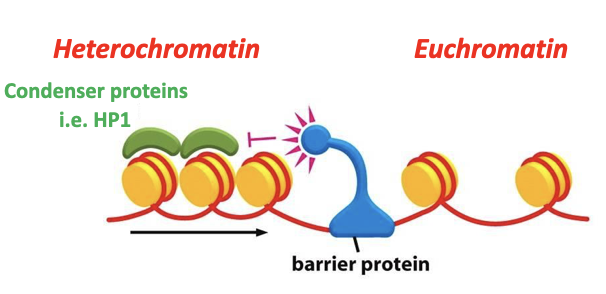

heterochromatin

A smaller proportion of human chromosomes is in the form of heterochromatin, where the chromatin is more permanently compacted

Forms via condenser proteins

Not dynamic (cannot reverse compactness)

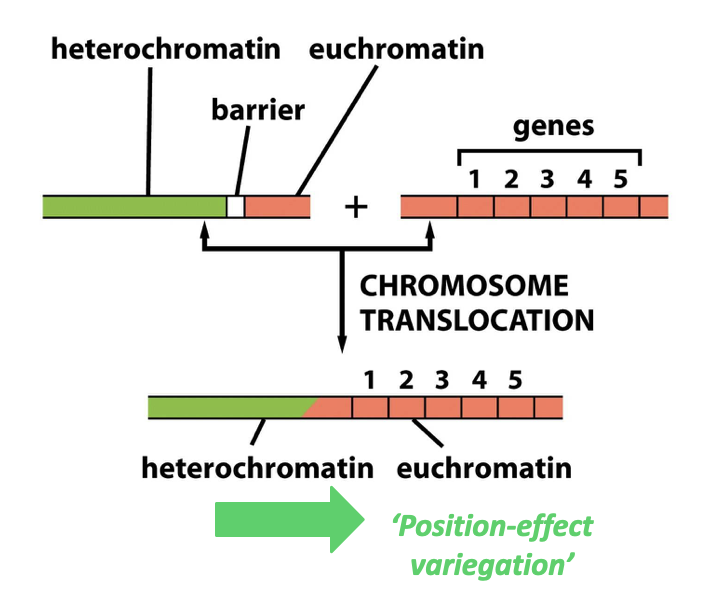

Barrier elements recruit barrier proteins

Prevent heterochromatin spilling into euchromatin

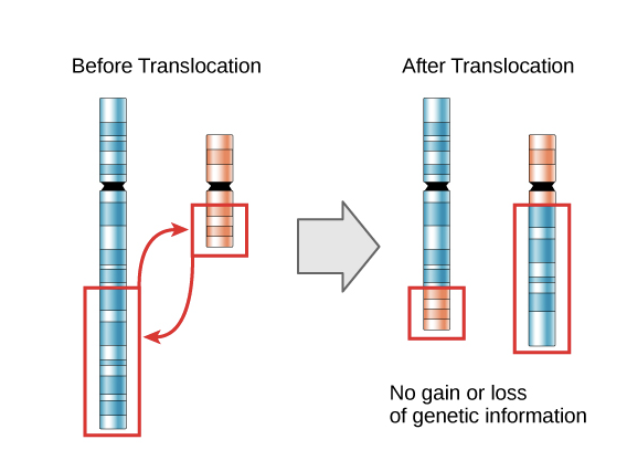

Can be lost following a chromosomal translocation

spilling of heterochromatin

If heterochromatin spills = position effect variegation

Shuts off all the genes in the euchromatin

Heterochromatin has a tendency to spread (e.g. into neighbouring euchromatic regions)

Molecular mechanisms exist to prevent this

structural heterochromatin

Structural heterochromatin usually contains repetitive DNA sequences known as satellite DNA

It is found in structural elements such as centromeres and importantly in telomeres

Prevent fusion of chromosomes

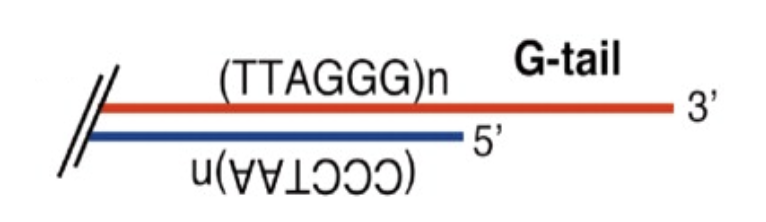

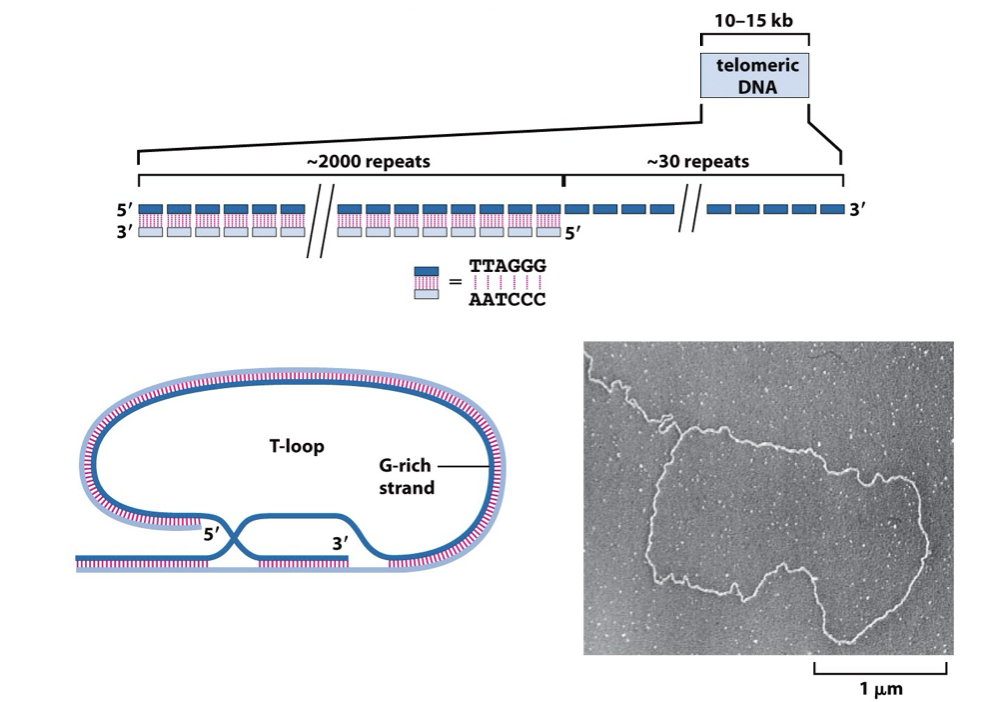

Telomeric DNA sequences are composed of long arrays (10-15 kilobases) of short tandem repeats

G rich strand = longer, resulting in an overhang called the G-tail (around 30 repeats)

C rich strand = shorter

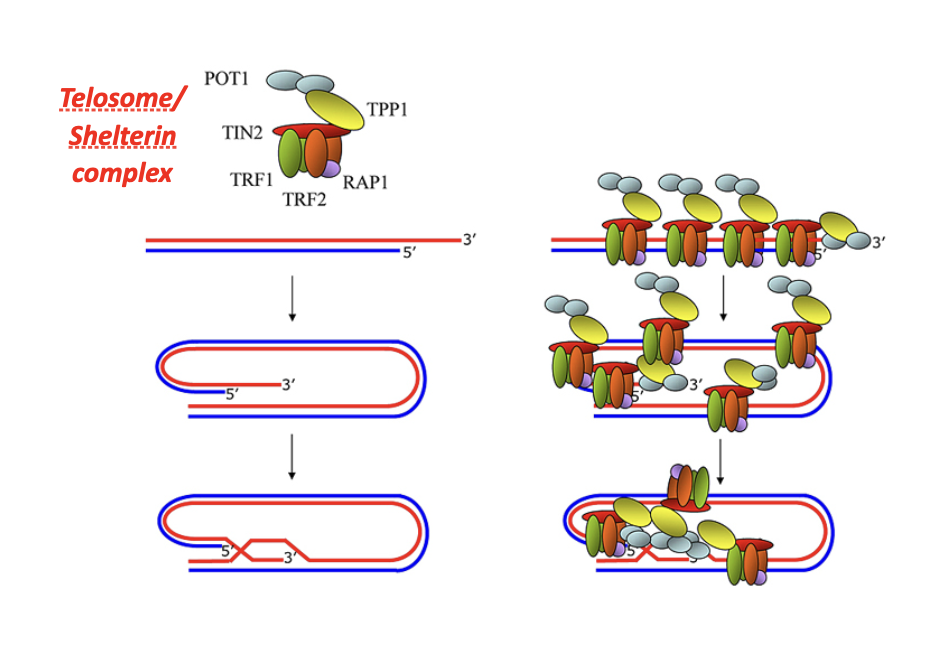

G-tail

Protects chromosome ends

Prevents chromosome ends from being recognized as DNA double-strand breaks

Avoids activation of DNA damage response pathways

Enables telomere capping

G-tail folds back to form a T-loop

The T-loop physically hides the chromosome end

Recruits shelterin complex

Binds telomere-specific proteins (e.g. TRF1, TRF2, POT1)

Shelterin stabilizes telomere structure and maintains heterochromatin

Prevents end-to-end fusions

Blocks non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) at chromosome ends

Maintains genomic stability

Ensures proper chromosome maintenance across cell divisions

Facilitates telomere replication

Provides a substrate for telomerase to extend telomeres

function of structural heterochromatin

Maintains chromosome structural integrity

Provides mechanical stability to chromosomes

Located at repetitive DNA regions

Found at centromeres, telomeres, and other repeat-rich regions

Ensures proper chromosome segregation

Centromeric heterochromatin is essential for kinetochore formation

Prevents mis-segregation during mitosis and meiosis

Suppresses recombination

Prevents homologous recombination between repetitive sequences

Reduces chromosomal rearrangements

Silences repetitive DNA

Transcriptionally inactive

Prevents expression of transposons and satellite DNA

Protects genome stability

Limits insertional mutagenesis by mobile elements

Maintains nuclear organization

Anchors chromatin to the nuclear periphery

Contributes to higher-order chromatin architecture

Defines chromosomal domains

Acts as a boundary separating active euchromatin regions

Epigenetically maintained

Characterized by DNA methylation

Enriched in H3K9me3 and HP1 proteins

Evolutionarily conserved

Present in most eukaryotes with similar structural roles

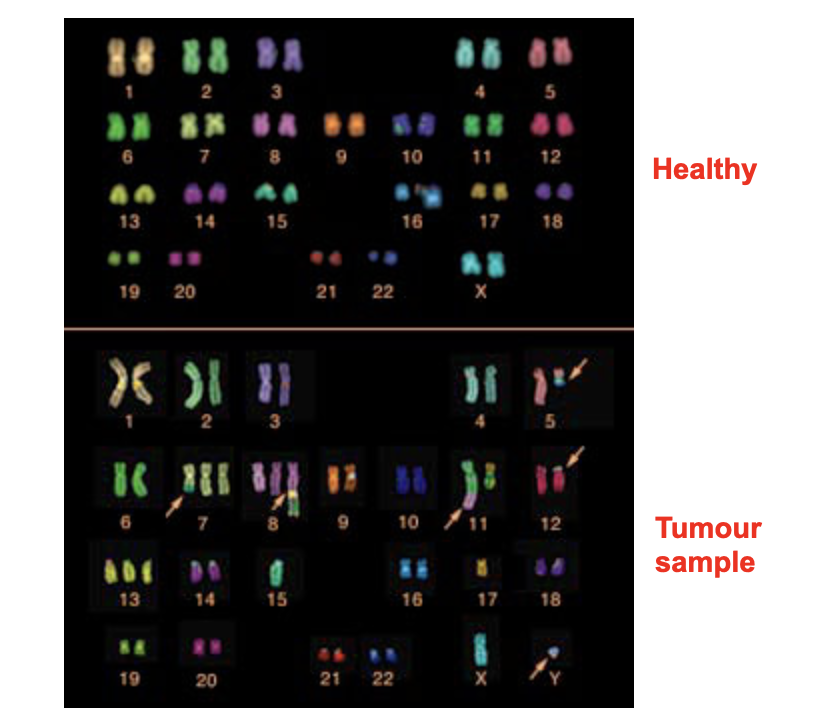

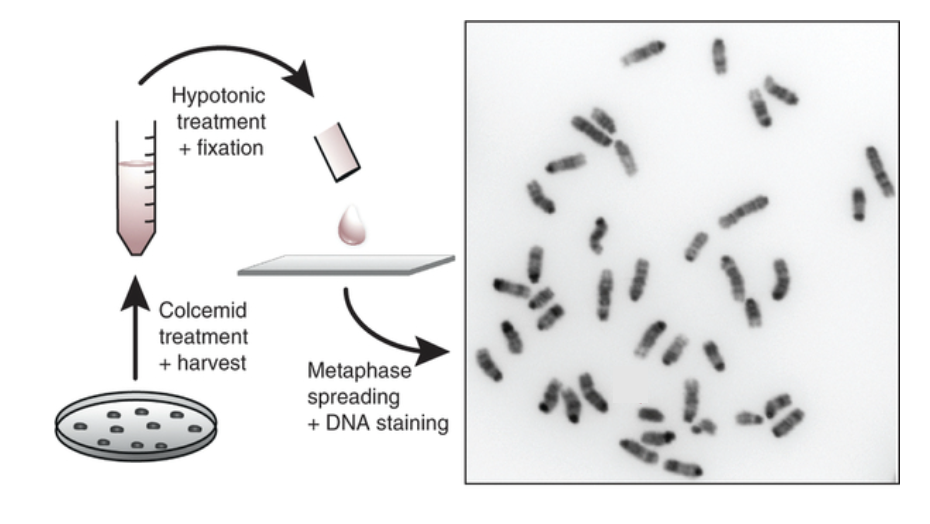

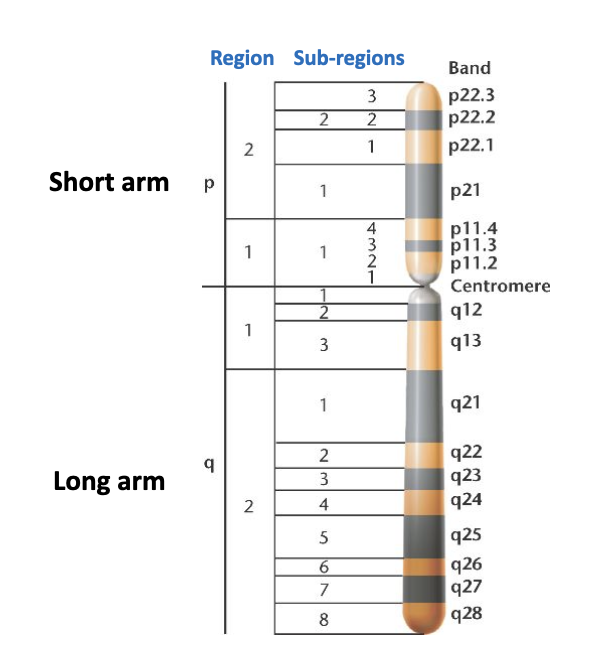

cytogenetics

Chromosomes from cell preparations can be 'spread' on a microscopic slide for analysis

Want to collect them in metaphase

As they are more condensed

Can be distinguished from each other

Chromosomes in prometaphase are less compacted and thus reveal more detail

Can find structural features

hypotonic treatment

Cells are placed in a hypotonic solution (e.g. 0.075 M KCl)

Water enters cells by osmosis

Cells swell due to increased internal pressure

Nuclear membrane weakens and ruptures

Chromosomes spread apart within the swollen cell

Cell is then fixed (e.g. methanol:acetic acid) to preserve chromosome structure

Chromosomes are dropped onto a slide for staining and analysis

Stains create a banding pattern

Can distinguish one chromosome from another

Using karyotyping

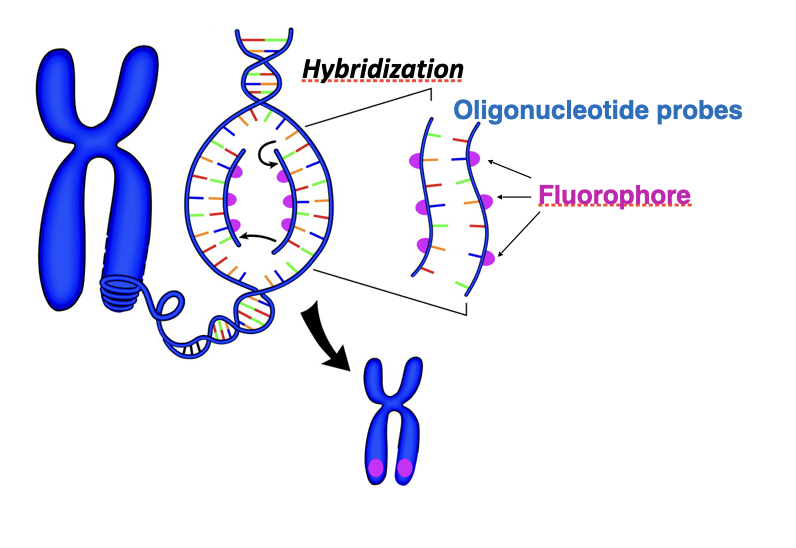

molecular cytogenetics

Higher resolution analysis (e.g. detection of specific DNA sequences within chromosomes)

Achieved by designing and chemically synthesising an 'oligonucleotide probe' directed against a target DNA sequence

Labelled with a fluorophore

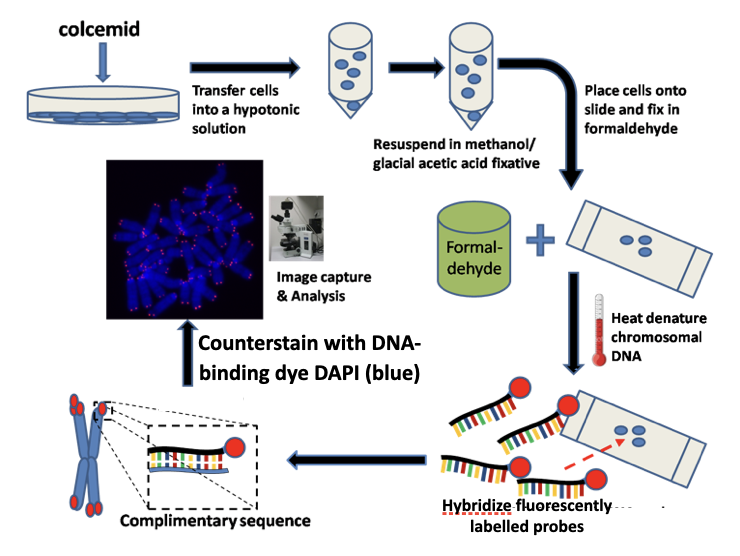

how does FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridisation) work

Purpose:

Detects and localizes specific DNA (or RNA) sequences on chromosomes or in cells

Starting material:

Metaphase chromosomes or interphase nuclei fixed on a slide

Denaturation:

Chromosomal DNA is heated or chemically treated

Double-stranded DNA separates into single strands

Probe preparation:

Short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide probes

Labelled with a fluorescent dye

Hybridization:

Probe is applied to the slide

Incubation allows probe to find and bind its complementary sequence

Washing:

Removes unbound or weakly bound probes

Ensures specific binding

Detection:

Slide viewed under a fluorescence microscope

Bound probes appear as bright fluorescent signals

how does the oligonucleotide probe attach

Base pairing

Probe binds by complementary base pairing

A–T and G–C hydrogen bonds form between probe and target DNA

Hybridization conditions

Temperature, salt concentration, and time control stringency

High stringency → only perfect matches bind

Low stringency → partial mismatches may bind

No covalent bonds

Attachment is non-covalent (hydrogen bonds only)

Binding is reversible under denaturing conditions

Probe length matters

Short oligos → high specificity

Longer probes → stronger binding, lower specificity

chromosome painting

Uses a large cocktail of probes that will bind to many different locations along the length of a single type of chromosome

Spectral karyotyping (SKY) can allow for the entire set of chromosomes to be analysed