Unit 6 APUSH Vocab

1/106

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Unit 6 APUSH (1865-98)

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

107 Terms

Transcontinental Railroads

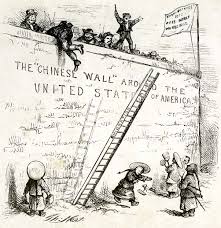

The development of the western United States after 1865 differed from the settlement patterns before because of industrialization. The biggest difference was the building of transcontinental railroads across the US. The great age of railroad building happened at the same time settlements were being built in the last Western Frontiers. Railroads not only promoted the settlement of the Great Plains, but also connected the West and East together economically, creating a national market. During the Civil War, Congress authorized land grants and loans for the building of the first transcontinental Railroad to connect California with the rest of the Union. Two newly incorporated railroad companies divided the work, The Union Pacific (UP) started in Omaha, Nebraska and built West across the Great Plains. The UP would employ thousands of war veterans and Irish immigrants under the direction of General Grenville Dodge. The Central Pacific started from Sacramento, California, and built Eastward. Led by Charles Crocker, the workers, including as many as 20,000 Chinese immigrants, took on the great risks of laying track and blasting tunnels through the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The two railroads came together on May 10, 1869, at Promontory Point, Utah, where a golden spike was ceremoniously driven into the rail tie to make the linking of the Atlantic and Pacific states. In 1883, three other transcontinental railroads were completed. The Southern Pacific tied New Orleans to LA. The Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe linked Kansas City and LA. The Northern Pacific connected Duluth, Minnesota, with Seattle, Washington. In 1893, the Great Northern finished the fifth transcontinental railroad, which ran from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Seattle. Companies built many other short line and narrow-gauge railroads to open up the Western interior to settlement by miners, rangers, farmers, and business owners, leading to more towns and cities. Progress came with significant costs. The railroads helped to transform the West during this period, but many proved failures as businesses. They were built in areas with few customers and with little promise of returning a profit in the near term. The frenzied rush for the West’s natural resources seriously damaged the environment and nearly exterminated the buffalo. Most significantly, the American Indians who lived in the region paid a high human and cultural price.

Great American Desert

At first, the settlement and economic development of the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, and the Western Plateau did not seem promising. Before 1860, these lands between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Coast were known as “the Great American Desert” by pioneers passing through on the way to the green valleys of Oregon and the goldfields of California. The plains west of the 100th meridian had few trees and usually received less than 15 inches of rainfall a year, which was not considered enough moisture to support farming. Winter blizzards and hot dry summers discouraged settlement. However, after 1865 the Great Plains changed so dramatically that the former “frontier” largely vanished. By 1900, the great buffalo herds had been wiped out. The open western lands were fenced in by homesteads and ranchers, crisscrossed by steel rails, and modernized by new towns. Ten new western states had been carved out of the last frontier. Only Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma remained as territories awaiting statehood at the end of the century. California’s great gold rush of 1849 set the pattern for other gold rushes. Individual prospectors poured into the region and used a method called placer mining to search for traces of gold in mountain streams. They needed only simple tools such as shovels and washing pans. Following these individuals came mining companies that could employ deep-shaft mining that required expensive equipment and the resources of wealthy investors. As the mines developed, companies employed experienced miners from Europe, Latin America, and China. The California Gold Rush was only the first of a series of gold strikes and silver strikes in what became the state of South Dakota, Colorado, Montana, Idaho, Nevada, and Arizona. These strikes kept a steady flow of hopeful prospectors pushing into the western mountains into the 1890s that helped settle the West. The discovery of gold near Pike’s peak, Colorado,in 1859 brought nearly 100,000 miners to the area. In the same year, the discovery of the fabulous Comstock Lode led to Nevada entering the Union in 1864. Idaho and Montana also received early statehood, largely because of mining booms. Rich strikes created boomtowns, overnight towns that became infamous for saloons, dance-hall girls, and vigilante justice. Many of these, however, became lonely ghost twins within a few years after the gold or silver ran out. The mining towns that endured and grew evolved more like industrial cities than the frontier towns depicted in western films. For example, Nevada’s Virginia City, added theaters, churches, newspapers, schools, libraries, railroads, and police. Mark Twain started his career as a writer working on a Virginia City newspaper in the early 1860s. A few twins that served the mines, such as San Francisco, Sacramento, and Denver, expanded into prosperous cities. The economic potential of the vast open grasslands that reached from Texas to Canada was realized by ranchers in the decades after the Civil War. Earlier, cattle had been raised and rounded up in Texas on a small scale by Mexican cowboys, or vaqueros. The radiations of the cattle business in the late 1800s, like the hard “Texas” longhorn cattle, were borrowed from the Mexicans. By the 1860s, wild herds of about 5 million head of cattle roamed freely over the Texas grasslands. The Texas cattle business was easy to get into because both the cattle and the grass were free. The construction of railroads into Kansas after the war opened up eastern markets for the Texas cattle. Joseph G. McCoy built the first stockyards in the region, at Abilene, Kansas. Those stock yards held cattle that could be sold in Chicago for the high price of $30 to $50 per head. Dodge City and other cow towns sprang up along the railroads to handle the millions of cattle driven up the Chisholm, Goodnight-loving, and other trails out of Texas during the 1860s and 70s. The cowboys, many of whom were African Americans or Mexicans, received about a dollar a day for their dangerous work.

Barbed Wire

The long cattle drives began to end in the 1880s. Overgrazing destroyed the grass, and a winter blizzard and drought of 1885-6 killed of 90% of the cattle. Another factor that closed down the cattle frontier was the arrival of homesteaders, who used barbed wire fencing to cut off access to the formerly open range. Wealthy cattle owners turned to developing huge ranches and using scientific ranching techniques. They raised new breeds of cattle that produced more tender beef by feeding the cattle hay and grains. The Wild West was largely tamed by the 1890s. HOwever, in these few decades, Americans’ eating habits changed from pork to beef, and people created the enduring legend of the rugged, self-reliant American cowboy.

Homestead Act

The Homestead Act of 1862 encouraged farming on the Great Plains by offering 160 acres of public land fee to any family that settled on it for a period of five years. The promise of free land combined with the promotions of railroads and land speculators induced hundreds of thousands of native-born and immigrant families ot attempt to farm the Great Plains between 1870 and 1900. About 500,000 families took advantage of the Homestead Act. However, five times that number had to purchase their land, because the best public lands often ended up in the possession of railroad companies and speculators. The first “sodbusters'“ on the dry and treeless palin’s often built their homes of sod bricks. Extremes of hot and cold weather, plagues of grasshoppers, and the lonesome life on the plains challenged even the most resourceful of the pioneer families. Water was scarce, and wood for fences was almost non-existent. The invention of barbed wire by Joseph Glidden in 1874 helped farmers to fence in tehri lands on the lumber-scarce plains. Using mail-order windmills to drill deep wells provided some water. Even so, many homesteaders discovered too late that 160 acres was not adequate for farming the Great Plains. Long spells of severe weather, together with falling prices for their crops and the cost of new machinery, caused the failure of two-thirds of the homesteaders’ farms on the Great Plains by 1900. Western Kansas alone lost half of its population between 1888 and 1892. Those who managed to survive adopted “Dry Farming” and deep-plowing techniques to make the most of the moisture available. They also learned to plant hardy strains of Russian wheat that withstood the extreme weather. Ultimately, government programs to build dams and irrigation systems saved many western farmers, as humans reshaped the rivers and physical environment of the West to provide water for agriculture.

National Grange Movement

By the end of the 1800s, farmers had become a minority within American society. While the number of US farms more than doubled between 1865 and 1900, people working as farmers declined from 60% of the working population in 1860 to less than 37% in 1900. At the same time, farmers faced growing economic threats from railroads, banks, and global markets. With every passing decade in the late 1800s, farming became increasingly commercialized —- and also more specialized. Northern and western farmers of the late 19th century concentrated on raising single cash crops, such as corn or wheat, for both national and international markets. As consumers, farmers began to procure their food from the stores in town and their manufacture goods from mail-order catalogs sent to them by Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck. As producers, farmers became more dependent on large and expensive machines, such as steam engines, seeders, and reaper-threshers combines. Larger farms were run like factories. Unable to afford the new equipment, small, marginal farms could not compete and, in many cases, were driven out of business. Increased production of crops such as wheat and corn in the United States as well as in Argentina, Russia, and Canada drove prices down for farmers around the world. In the UNited States, since the money supply was not growing as fast as the economy, each dollar became worth more. This put more downward pressure on prices, resulting in deflation. As prices fell, farmers with mortgages faced both high interest rates and the need to grow more and more to pay off old debts. Of course, increased production only lowered prices. The predictable results of this vicious circle were more debts, foreclosures by banks, and more independent farmers forced to become tenants and sharecroppers. Farmers felt victimized by impersonal forces of the larger national economy. Industrial corporations were able to keep prices high on manufactured goods by forming monopolistic trusts. Wholesalers and retailers took their cut before selling to farmers. Railroads, warehouses, and elevators took what little profit remained by charging high or discriminatory rates for the shipment and storage of grain. Railroads would often charge more for short hauls on line with no competition than for long hauls on lines with competition. Taxes also seemed unfair to farmers. Local and state governments taxed property and land heavily but did not tax income from stocks and bonds. The tariffs protecting various American industries were viewed as just another unfair tax paid by farmers and consumers for the benefit of the industrialists. A long tradition of Independence and individualism restrained farmers from taking collective action. FInally, however, they began to organize for their common interests and protection. The National Grange of Patrons of Husbandry was organized in 1868 by Oliver H Kelley Primarily as a social and educational organization for farmers and their families. Within five years, chapters of the Grange exists in almost every state, with the most in the Midwest. As the National Grange Movement expanded, it became active in economics and politics to defend members against middlemen, trusts, and railroads. For example, Grangers established cooperatives (Businesses owned and run by the farmer to save the costs charged by middlemen). In Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, the Grangers, with help from local businesses, successfully lobbied their state legislatures to pass laws regulating the rates charged by railroads and elevators. Other Granger laws made it illegal for railroads to fix prices by means of pools and to give rebated to privileged customers. In the landmark case of Munn v. Illinois (1877), the Supreme Court upheld the right of a state to regulate businesses of a public nature, such as railroads. Farmers also expressed their discontent by forming state and regional groups known as Farmer’s alliances. Like the Grange, the alliances taught about scientific farming methods. Unlike the Grange, alliances always had the goal of economic and political action. Hence, the alliance movement had serious potential for creating an independent national political party. By 1890, about 1 million farmers had joined farmers’ alliances. In the South, both poor White and Black farmers joined the movement. That potential nearly became reality in 1890 when a national organization of farmers, the national Alliance, met in Ocala, Florida, to address the problems of rural America. The Alliance attacked both major parties as subservient to Wall Street bankers and big business. Ocala delegates created the Ocala Platform that called for significant reforms:

Direct election of US senators (in original US Constitution senators elected from state legislatures)

Lower tariff rates

A graduated income tax

A new banking system regulated by the federal government

In addition, the Alliance platform demanded that Treasury notes and silver be used to increase the amount of money in circulation. Farmers wanted to increase the supply of money in order to create inflation, thereby raising crop prices. The platform also proposed federal storage for farmers’ crops and federal loans, freeing farmers from dependency on middlemen and creditors. The alliances stopped short of forming a political party. However, local and state candidates who support alliance goals received decisive electoral support from farmers. Many of the reform ideas of the Grange and the farmers alliances would become part of the Populist movement, which would shake the foundations of the two-party system in the elections of 1892 and 1896.

Granger laws

As the National Grange Movement expanded, it became active in economics and politics to defend members against middlemen, trusts, and railroads. For example, Grangers established cooperatives (Businesses owned and run by the farmer to save the costs charged by middlemen). In Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, the Grangers, with help from local businesses, successfully lobbied their state legislatures to pass laws regulating the rates charged by railroads and elevators. Other Granger laws made it illegal for railroads to fix prices by means of pools and to give rebated to privileged customers. In the landmark case of Munn v. Illinois (1877), the Supreme Court upheld the right of a state to regulate businesses of a public nature, such as railroads.

Munn v. Illinois

In Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, the Grangers, with help from local businesses, successfully lobbied their state legislatures to pass laws regulating the rates charged by railroads and elevators. Other Granger laws made it illegal for railroads to fix prices by means of pools and to give rebated to privileged customers. In the landmark case of Munn v. Illinois (1877), the Supreme Court upheld the right of a state to regulate businesses of a public nature, such as railroads.

Frederick Jackson Turner

The historical perspective on the social and cultural development of the West has changed since the 1890s. The Oklahoma Territory, once set aside for the use of American Indians, was opened for settlement in 1889, and hundreds of homesteaders took part in the last great land rush in the West. In 1890 the US Census Bureau declared that the entire frontier—except for a few pockets— had been settled. Three years after the Census Bureau declaration, historian Frederick Jackson Turner published a provocative, influential essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” He presented the settling of the frontier as an evolutionary process of building civilization. Into an untamed wilderness came wave after wave of people. The first were hunters. Following them came cattle ranchers, miners, and farmers. Then the last would be the foundation of towns and cities. Turner argued that 300 years of frontier life had shaped American culture, promoting independence, individualism, inventiveness, practical-mindedness, and democracy. But people also became wasteful of natural resources Historians have argued against Frederick’s claims, notably that towns in the frontier provided huge importance. For example, 19th century “boosters” tried to create settlements overnight in the middle of nowhere in the frontier. Urban markets also played a huge role in the frontier. The cattle frontier was able to have the successes that it had because it was connected to urban markets such as Chicago due to the railroads that were in the West. The development of the Western Frontier became integrated with the development of cities and towns. The closing of the frontier scared Frederick, who viewed the frontier as way to release discontent in American society. The frontier was always a place to have a fresh start, but Frederick worried that without it the US would follow the same class struggles and society as Europe. While many debate over Frederick's thesis, the biggest migration of the time was people moving from rural to urban, simply put there was more opportunity in urban areas. Not only was the West coming to an end, but the decline of rural America.

“The Significance of the Frontier in American History” (1893)

Three years after the Census Bureau declaration, historian Frederick Jackson Turner published a provocative, influential essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” He presented the settling of the frontier as an evolutionary process of building civilization. Into an untamed wilderness came wave after wave of people. The first were hunters. Following them came cattle ranchers, miners, and farmers. Then the last would be the foundation of towns and cities. Turner argued that 300 years of frontier life had shaped American culture, promoting independence, individualism, inventiveness, practical-mindedness, and democracy. But people also became wasteful of natural resources Historians have argued against Frederick’s claims, notably that towns in the frontier provided huge importance. For example, 19th century “boosters” tried to create settlements overnight in the middle of nowhere in the frontier. Urban markets also played a huge role in the frontier. The cattle frontier was able to have the successes that it had because it was connected to urban markets such as Chicago due to the railroads that were in the West. The development of the Western Frontier became integrated with the development of cities and towns. The closing of the frontier scared Frederick, who viewed the frontier as way to release discontent in American society. The frontier was always a place to have a fresh start, but Frederick worried that without it the US would follow the same class struggles and society as Europe. While many debate over Frederick's thesis, the biggest migration of the time was people moving from rural to urban, simply put there was more opportunity in urban areas. Not only was the West coming to an end, but the decline of rural America.

Little Big Horn

The Native Americans who lived in the West in 1865 belonged to a wide and diverse ray of cultures and tribes. For example, New Mexico and Arizona had groups such as the Zuni and Hopi living permanent settlements raising corn and livestock. The Navajo and Apache people of the Southwest were nomadic hunters who eventually adapted a more settled lifestyle, including the development of arts and crafts. In the Northwest, groups such as the Chinook and Shasta created complex communities with the abundance of fish and game. But, around 2/3rd of Native Americans around this time lived in the Great Plains. Most notably tribes include the Sioux, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Crow, and Comanche. These tribes let go of farming in colonial times after they were introduced to the horse by the Spanish. By the 1700s, they had become extremely skillful horsemen who centered their way of life around the Buffalo. Even though they lived in tribes of several thousand, they would groups themselves up in bands of 300-500. In the late 19th century, most of the conflicts between White settlers and Native Americans was due to the settlers lack of understanding of the lifestyle of the Native Americans. In the 1830s, President Andrew Jackson moved Native Americans in the East to the West with the Indian Removal Act, this was partly under the belief that lands west of the Mississippi River would forever be “Indian Country”. This expectation would soon fail, as settlers began moving to Oregon through the Oregon trail and the establishment of a transcontinental Railroad. Around this time, in 1851, negotiations began (councils) at fort Laramie (Wyoming) and Fort Atkinson (Wisconsin). The Federal Government would assign large tracts of land to Great Plains tribes, reservations, with definite boundaries. However, most of the plain tribes would refuse to restrict their movement to set boundaries and instead follow the normal migration of the buffalo. In the late 1800s, the settlement of miners, ranchers, and homesteaders on Native American land led to conflict. Fighting between Native Americans and US troops were extremely brutal, the US Army would often respond with large scale massacres of Native Americans in response. In 1866, during the Sioux War, the Great Plains tribes were able to gain an upper hand when a warband of Sioux destroyed an entire army column under Captain William Fetterman. After these wars, another round of treaties would occur where the Federal Government tried to isolate Native American tribes further on even smaller reservations. However, they did “promise” government support. But, gold miners refused to stay off Native American land of gold was found, which happened in the Dakota Black Hills. Very quickly, minor chiefs who weren’t involved in the treaty making and younger warriors would denounce the treaties and try to take back their land. A new round of conflicts began in the 1870s. The Indian Appropriation Act of 1871 ended the recognition of tribes as independent nations by the Federal government and ended all negotiations of treaties between Native American tribes and Congress. A few conflicts that occurred were the Red River War against the Comanche tribes in the Southern plains and the second Sioux War led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse in the Northern Plains. Before the Sioux were defeated, they attempted and succeeded an ambush against Colonel George Custer’s troops at Little Big Horn in 1876. They devastated Colonel’s troops. However, in the Northwest, Chief Joseph’s courageous effort to lead a band of the Nez Perce into Canada failed and lead to surrender in 1877. The constant pressure of the US troops against tribe after tribe force them to comply with the Federal Government’s terms, even though the government violated the treaties. To add on, the harrowing decline of the Buffalo in the 1880s led to the end of the Plain’s lifestyle. Plains Native Americans had to change their traditions as a nomadic hunting culture.

Ghost Dance Movement

The last effort of Native Americans to resist the Federal Government was the spread of a new religious movement called the Ghost Dance Movement. Leaders believed that the dance would eventually bring back prosperity for Native Americans on the American Continent. The famous Sioux medicine man Sitting Bull was killed during his arrest, as the federal government began a brutal campaign to suppress the movement. Then in December of 1890, the US Army gunned down more than 200 Native Americans at the “battle” (massacre) of Wounded Knee in the Dakotas. This final act marked the end of the wars against the Native Americans on the prairies.

Helen Hunt Jackson

The crimes and injustices against Native Americans were chronicled in Helen Hunt Jackson’s best-selling book, A Century of Dishonor (1881). Although it created sympathy for Native Americans, especially in the East, it also created support for the end of Native American culture through assimilation. Reformers advocated for education, job training, and conversion to Christianity as a way to become “more civilized” and assimilate. People even created boarding schools to separate young Native American children from society and try to assimilate them to White culture and society, such as the Carlisle School in Pennsylvania.

Dawes Act of 1887

A new phase of the relationship between Native Americans and the federal government began in 1887. The Dawes Act of 1887 was passed, which was designed to break up tribal organizations, which was viewed by many Americans as preventing Native Americans from becoming “civilized”. The Dawes Act divided the tribal lands into plots of 160 acres, depending on family size. US citizenship would be granted to those who stayed on the land for 25 years and adopted more “civilized ways”. Under the Dawes Act, the Federal Government gave out 47 million acres to Native Americans. However, 90 million of Native American land was instead sold to White settlers, often the best land. By the start of the next century, the Native American population had declined due to disease and poverty to just 200,000 people.

Indian Reorganization Act

In 1924, partially recognizing that assimilation had failed, the federal government gave citizenship to all Native Americans regardless if they had followed the Dawes Act. In FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (1934) which promoted the reestablishment of tribal organizations and culture. Since then, the number of people who identify as Native Americans has increased. Today, 3 million identify as Native Americans, as well as 500 tribes now live in the US.

Santa Fe Trail

Mexico’s independence from Spain 1821 increased the trade and cultural exchange with the US. The Santa Fe Trail, an almost 1,000 mile overland route between Sante Fe, New Mexico and western Missouri linked the regions. The trail opens up the Spanish-speaking Southwest to economic development and settlement. It was a vital link until the railroad in 1880. Mexican landowners in the Southwest and California were guaranteed their rights and citizenship after the Mexican American War. However, out-dated legal proceedings often resulted in the selling or loss of lands to new Anglo settlers. Hispanic cultures were preserved in the US through large Spanish speaking populations, such as the New Mexico territories, the border towns, and California. During this time, Mexican-Americans were moving out on to the West to find work. Many found jobs in the sugar beet fields and mines in Colorado, and building railroads in the region. Before 1917, the border with Mexico was open, and few records were kept for either seasonal workers or permanent settlers. Mexicans, like other European immigrants, were drawn to the explosive economic opportunity of the region. Mexican American, White settlers, and Native Americans competed for land and its resources.

John Muir

The worries of deforestation led to the conservation movements. Breathtaking paintings and photographs of western landscapes helped convince Congress to preserve Western icons such as Yosemite Valley, a state park in 1864 (national in 1890) and Yellowstone become the first national park in 1872. In the 1800s, Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz advocated for the creation of forest reserves and a federal forest service to protect federal lands from exploitation. Presidents Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland reserved 33 million acres of national timber. With the ending of the frontier, Americans become more concerned about the loss of public lands and the natural environment. The Forest reserve Acts of 1891 and the Forest Management Act of 1897 withdrew federal timberlands from development and regulated the industry. While most “conservationists” believed in scientific management and regulated used of natural resources, “preservationists”, such as as John Muir, a leading founder of the Sierra Club in 1892, went further by wanting no human interference in hunting grounds. The creation of Arbor day in 1872, a day dedicated to planting trees, and the educational efforts of the Audubon Society and the Sierra Club reflected the growing environmental awareness by 1900.

Sierra Club

The worries of deforestation led to the conservation movements. Breathtaking paintings and photographs of western landscapes helped convince Congress to preserve Western icons such as Yosemite Valley, a state park in 1864 (national in 1890) and Yellowstone become the first national park in 1872. In the 1800s, Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz advocated for the creation of forest reserves and a federal forest service to protect federal lands from exploitation. Presidents Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland reserved 33 million acres of national timber. With the ending of the frontier, Americans become more concerned about the loss of public lands and the natural environment. The Forest reserve Acts of 1891 and the Forest Management Act of 1897 withdrew federal timberlands from development and regulated the industry. While most “conservationists” believed in scientific management and regulated used of natural resources, “preservationists”, such as as John Muir, a leading founder of the Sierra Club in 1892, went further by wanting no human interference in hunting grounds. The creation of Arbor day in 1872, a day dedicated to planting trees, and the educational efforts of the Audubon Society and the Sierra Club reflected the growing environmental awareness by 1900.

“New South”

While the West was being developed, the South was recovering from the Civil War. Some Southerners hoped for a “New South” built on industrial growth, modernized transportation, improved race relations, and a self-sufficient economy. However, its agricultural past and racism hindered attempts to fully realize this dream. Henry Grady, an editor for the Atlanta Constitution, became a champion for a “New South” with economic diversity and laissez-faire capitalism in his editorials (opinions). To attract business, local governments would provide tax exemptions to investors and the promise of low-wage labor. The growth of cities, the textile industry, and improved railroad lines in the South symbolized efforts to create such “New South”. Some examples include:

Birmingham, Alabama, developed into of the nation’s main steel producers

Memphis, Tennessee, prospered as a huge hub for the timber industry.

Richmond, Virginia, became the nation’s leading city in the tobacco industry after being the capital of the former Confederacy

Georgia, North, and South Carolina would overtake the New England states in producing textiles. By 1900, the South had around 400 cotton mills that had 100,000 white workers. Southern railroad companies quickly converted the gauges for railroads in the South to the same as the East and West, connecting the South to the national rail network. The South’s rate of postwar growth equaled or surpassed that of the rest in the country in population, industry, and railroads from 1865-1900. However two factors slowed the industrial progress of the South. 1: Northern Financing dominated much of the economy, Northern investors controlled 3/4ths of the Southern railroads and by 1900 the steel industry. Large amounts of profits went to the pockets of investors and financiers in the North instead of recirculating in the South. Adding on to this, was that the South failed to expand public education in the state and local level. They didn’t create technical and engineering schools for White or Black residents like the North had done. As a result, few Southerners had skills needed in the Industrial Development. Without a good education, the Southern workforce faced many limiting economic opportunities. Southern industrial workers (94% were White), earned half that national average and worked longer hours than any other work elsewhere.

George Washington Carver

While industry did grow in the South, the region still was largely agricultural and also still the poorest. By 1900, more than half of the region’s Whiter farmers and ¾ of the Blacker farmers were either tenant farmers or sharecroppers. Since people were poor, and the profits of industry flowed North, Southern banks had little money to lend to farmers. This shortage caused farmers to borrow supplies from local merchants with a lien, or mortgage, on their crops. This combination caused farmers to become serfs tied to the land by debt. They barely got by. The South’s postwar economy also remained tied to the growing of cotton. Between 1870 and 1900, cotton planting doubled. Increasing the amount of cotton only made things worse since the result of more cotton lowered prices by more than 50% by the 1890s. Per Capita income in the South declined while farmers lost their farms. Some Southern farmers wanted to diversify the crops they grew in order to escape the cycle of debt. George Washington Carver, an African Americans scientist at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, proposed that more farmers grow peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans. His work helped play an important role in helping shift the agriculture of the South to be more diverse. Despite some diversity, most small farmers in the South remained in a cycle of debt and poverty. Just like the North and West, hard times produced discontent. By 1890, the Farmer’s Southern Alliance claimed more than 1 million members, while a separate group for African Americans, the Colored Farmer’s National Alliance, had around 250,000 members. Both organizations focused on political reforms to help solve farmers’ issues. If poor Black and White farmers would have come together in the South, they would have become a potent political force. However, racial attitudes of White people and economic interests of the upper class in the South stood in the way.

Tuskegee Institute

Some Southern farmers wanted to diversify the crops they grew in order to escape the cycle of debt. George Washington Carver, an African Americans scientist at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, proposed that more farmers grow peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans. His work helped play an important role in helping shift the agriculture of the South to be more diverse. Despite some diversity, most small farmers in the South remained in a cycle of debt and poverty.

Civil Rights Cases of 1883

When Reconstruction ended in 1877, the North withdrew protections of African Americans and left the South to solve their own problems. Democratic politicians who were in power, known as redeemers, won support from the business community and white supremacists. White supremacists wanted African Americans to be treated as inferior and create separate, or segregated, public facilities by race. The redeemers often used race to help deflect attention from real concerns such as tenant farming and the working conditions of the South. These redeemers discovered that they could exert political power by using the racial fears and racism of Whites. During Reconstruction, federal laws helped protect African Americans from discrimination by local and state governments. However, starting in the late 1870s, the US Supreme Court struck down these laws. In the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, the Court ruled that the government can’t ban racial discrimination done by private citizens and businesses, which included railroads and hotels, used by the public.

Plessy v. Ferguson

In 1896, in the major case Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court upheld a Louisiana State law that created “separate but equal accommodations” White and Black railroad passengers. The Court declared that Louisiana didn’t violate the 14th Amendment’s “equal protections” clause.

Jim Crow laws

The federal court decisions of the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 as well as Plessy v. Ferguson, created a wave of segregation laws, commonly known as Jim Crow laws. These laws, originally from 1870 but being readopted, segregated washrooms, drinking fountains, park benches, and most public spaces. Only streets and most stores was not restricted according to a person’s race.

literacy tests

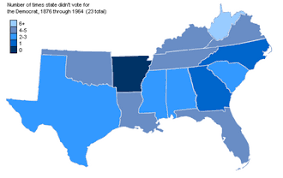

Other discriminatory laws resulted in the disenfranchisement of Black voters in 1900. In Louisiana for example, 130,334 Black voters were registered in 1896, however by 1904 only 1,342 were (a 99% decrease). Southern states created various political and legal devices to prevent African Americans from voting, among the most common were literacy tests, poll taxes, and White only primaries. Many Southern states also adopted grandfather clauses, which allowed a man to vote if his grandfather had voted in elections before Reconstruction. The Supreme Court again approved such tests in a case in 1898. Other discrimination occurred too in the South, African Americans couldn’t serve on juries. If convicted of a crime, African Americans often were given worse punishments than Whites. In some cases, African Americans accused of crimes didn’t get the formality of court-ordered sentences, instead they were lynched. Lynch mobs killed more than 1,400 Black men during the 1890s. Economic discrimination was also widespread, keeping most Southern African Americans out of skilled trades and factory jobs. Therefore, while poor Whites and immigrants learned the industrial skills that helped them rise to the middle class, African Americans often remained engaged in farming and low-paying domestic work.

poll taxes

Southern states created various political and legal devices to prevent African Americans from voting, among the most common were literacy tests, poll taxes, and White only primaries. Many Southern states also adopted grandfather clauses, which allowed a man to vote if his grandfather had voted in elections before Reconstruction. The Supreme Court again approved such tests in a case in 1898.

grandfather clauses

Southern states created various political and legal devices to prevent African Americans from voting, among the most common were literacy tests, poll taxes, and White only primaries. Many Southern states also adopted grandfather clauses, which allowed a man to vote if his grandfather had voted in elections before Reconstruction. The Supreme Court again approved such tests in a case in 1898.

Ida B. Wells

Segregation, disenfranchisement, and lynching left African Americans in the South oppressed but not powerless. Some responded with confrontation such as Ida B Wells. Ida B Wells was an editor of the Memphis Free Speech, a Black newspaper, who campaigned against lynching and the Jim Crow laws. Death threats as well as the destruction of her printing press caused Wells to carry her work from the North. Other Black leaders advocated for leaving the South, such as Bishop Henry Turned who formed the International Migration Society in 1894 to help Blacks move to Africa. Many African Americans moved to Kansas and Oklahoma.

Booker T. Washington

A third response was to accommodate it, advocated by Booker T Washington. Washington was born enslaved, but ended up graduating from Hampton Institute in Virginia. In 1881, he established an industrial and agriculture school for African Americans in Tuskegee, Alabama. African Americans learned skilled trades as well as the virtues of hard work, moderation, and economic self help from Washington. Washington viewed having money would empower African Americans more than a political ballot. Speaking at a convention in 1895 in Atlanta, Washington argued that Black Southerners as well as white Southerners shared a responsibility for making the South prosper, known as the Atlanta Compromise. He wanted African Americans to work hard at their jobs and not challenge segregation. In return, Whites should support education and some legal rights for African Americans. In 1900, Washington organized the National Negro Business League, which created 320 chapters across the country. The NNBL helped support business owned and operated by African Americans. Washington also further emphasized economic cooperation, as well as racial harmony, which won much praise from Whites such as Andrew Carnegie and President Theodore Roosevelt.

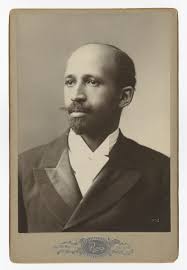

W. E. B. Du Bois

Later civil rights leaders had mixed feelings to Washington’s approach. Some criticized him as to willing to accept discrimination, such as WEB Du Bois who would demand an end to segregation after 1900. He also argued fro granting equal civil rights to all Americans. Some writers however praised Washington for paving the way for Black self-reliance because of his emphasis for supporting and creating Black-owned businesses.

Atlanta Compromise

Speaking at a convention in 1895 in Atlanta, Washington argued that Black Southerners as well as white Southerners shared a responsibility for making the South prosper, known as the Atlanta Compromise. He wanted African Americans to work hard at their jobs and not challenge segregation. In return, Whites should support education and some legal rights for African Americans. In 1900, Washington organized the National Negro Business League, which created 320 chapters across the country. The NNBL helped support businesses owned and operated by African Americans. Washington also further emphasized economic cooperation, as well as racial harmony, which won much praise from Whites such as Andrew Carnegie and President Theodore Roosevelt.

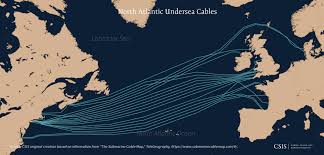

Transatlantic Cable

Important to the industrial development of the US after the Civil War were new inventions. Communication, transportation, basic industries, electric power, and urban growth were all improved through technological advancements. The first important change to the speed of communication was the creation of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse, created in 1844. By the start of the Civil War, electronic communication through the telegraph as well as quick transportation by the railroad were going hand and hand as well as becoming the new standard parts of modern society, especially in the North. After the war, Cyrus W Field created the transatlantic cable in 1866 where it was now possible to send messages across seas in minutes. By 1900, most of the world was now connected with hundreds/thousands of these cables that linked up all inhabited continents of the world creating instantaneous global communication. This communication internatilization markets, making prices for basic commodities such as as grains, coal, and steal at the mercy at international forces (often placed on local and smaller producers).

Alexander Graham Bell

More noteworthy inventions of the time in the late 19th century were the typewriter (67), the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell (76), the cash register (79), the calculating machine (87), and adding machine (88). These new products became essential for new business. Products that became widespread for consumers were GEorge Eastman’s Kodak camera (88), Lewis E. Waterman’s fountain pen (84), and King Gillette’s safety razor and blade (95).

Henry Bessemer

The technological breakthrough that launched the rise of heavy industry was the discovery of a new way to make large quantities of steel that also made it a better quality. In the 1850s, both Henry Bessemer in England and William Kelly in the US discovered that blasting air through molten iron produced high-quality steel. Because the Great Lakes had access to abundant coal reserves from Pennsylvania to Illinois and access to the iron ore of Minnesota’s Mesabi Range, it became a center of steel production.

Thomas Edison

Arguably one of the greatest inventors of the 19th century, Thomas Edison worked as a telegraph operator as a young man. In 1869, at 22, he patented his first invention that was a machine that recorded voices. Income from his early inventions allowed Edison to create a research laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, in 1876. This became the world’s first modern research lab, which was Edison’s “invention factory”. He declared that it would produce minor inventions every ten days and major ones every six months. This lab became one of Edison’s biggest accomplishments because it introduced the idea of mechanics and engineering as a group project than independent. Edison’s lab brought out more than a thousand inventions, including the phonograph, the dynamo for generating electricity, the mimeograph, and the motion picture camera. Edison is most well-known for his improvement of the incandescent lamp in 1879 (the first practical electric light bulb). Electric light revolutionized life, especially in cities, from the way people worked and how they shopped. During his lifetime, Edison became a mythic figure even though other inventors improved his work.

George Westinghouse

Another remarkable inventor of this time period was George Westinghouse, who held more than 400 patents. He was responsible for developing an air brake for railroads (69) and a transformer for producing high-voltage alternating current (AC). The last invention made it possible for the lighting of cities and the operation of electric street cars, subways, and electric powered machinery and appliances. Westinghouse and GEneral Electric came to dominate electric technology with their AC power supply systems, which came to replace Edison’s direct current. By 1900, various electric trades employed nearly a million people, making light and power of the nation’s largest and fastest growing industries.

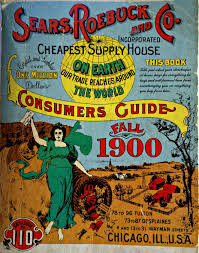

Mail-order companies

Development of how people moved and the building they lived in and worked in remade the urban landscape. Cities grew both outward and upward. Improvements in urban transportation mad e the growth of cities possible. During the walking cities of pre-Civil War America, people had little choice but to live within walking distance of their shops or jobs. Cities gave way to streetcar cities, in which people lived in residences many miles from their jobs and commuted to work on horse-drawn streetcars. By the 1890s, both horse drawn cars and cable cars were being replaced by electric trolleys, elevated railroads, and subways, which could transport people to urban residences even farther from the city’s commercial center. the building of massive steel suspension bridges such as New York’s Brooklyn Bridge (83) also made possible longer commutes between residential areas and city centers. As cities expanded outward, they also grew upward since the costs/value of land in the central business district increased, meaning building upward was more profitable. In 1885, Chicago became the home of the first skyscraper with a steel skeleton, a ten story building designed by William Le Baron Jenny. Structures of these size were made possible by such innovation as the Otis elevator and the central steam-heating system with radiators in every room. By 1900, steel-framed skyscrapers for offices of industry had replaced church spires as the dominant feature of American urban skylines. The increased output of US factories and invention of New consumer products allowed businesses to sell merchandise to a larger public. R.H. Macy in New York and Marshall Field in Chicago made the large department store popular in urban centers. Frank Woolworth’s five-and-dime stores brought nationwide chain stores to towns and urban neighborhoods. Two large mail-order companies, Sears, Roebuck and Co, and Montgomery Ward, used the improved rail system to ship to rural customers everything from hats to houses that people ordered from each company’s thick catalog. The Sears catalog became famous as the “wish book”. Packaged foods under such brand name as Kellogg and Post became common items in American homes. Refrigerated railroad cars and canning enabled Gustavus Swift and other Packers to change the eating habits of Americans with mass-produced meat and vegetable products. Advertising and new marketing techniques not only promoted a consumer economy but also create a consumer culture in which shopping became a favorite pastime.

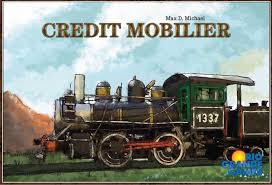

Cornelius Vanderbilt

While new tech helped pushed the development of industry and economic growth after 1865, the most important invention however was the creation of new management and financial structures that helped create large-scale industries. The increased desire for wealth created a desire for consolidation of businesses and wealth. The combination of business leadership, money, tech, markets, labor, and federal/state/local support was first seen in the development of the nation’s first big business—railroads. After the Civil War, railroad mileage increased by 5X in 35 years (1865 had 35,000 to 1900 193,000). The federal government helped this growth by providing low interest loans as well as giving away millions of acres of public land. Railroads helped create a market for goods nationally, and helped encourage mass production, consumption, and economic specialization. The resources also in railroad building caused other industries to grow such as coal and steel. Railroads also affected public life, prior to 1883 there were 144 local time zones. During this time, each community or region could determine when noon is. However, the American Railroad Association in 1883 put this to an end by dividing the country into four time zones. Railroad time became standard for all. The most important invention created by railroad companies was the creation of the modern stockholder corporation. Railroads required so much investment that they needed to create complex structures in finance, business, and regulation of competition. In the early decades of railroading (1830-60), the creation of different local and separate lines created different sized gauges and incompatible equipment. These problems were soon reduced after the Civil War where competing railroads started to become consolidating and integrated into trunk lines. Trunk lines are a major line between cities, smaller branches helped connect trunk lines to local towns. “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt used his millions from the steamboat business to merge local railroads into the New York Central Railroad (1867), which ran from New York City to Chicago. It operated more than 4,500 miles of track, other trunk lines such as the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and Pennsylvania Railroad connected eastern seaports with Chicago and other Midwestern cities. They helped set the standards of excellence and efficiency for the rest of the industry.

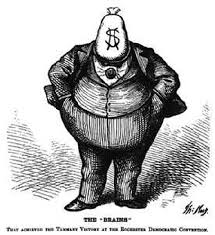

Jay Gould

However, railroads were not always efficient. Like other new tech through history, investors overbuilt in the 70s and 80s. Some companies suffered from mismanagement and fraud, speculators such as Jay Gould entered the railroad business for only quick profits and made their millions by selling off assets and watering stock (inflating value of a corporation’s assets and profits before selling its stock to the public). In order to survive, railroads competed by offering rebates (discounts) and kickbacks to favoured shoppers while charging a huge amount for freight rates to smaller customers such as farmers. Railroads also created pools where competing companies agreed secretly to fix rates and share traffic.

J. Pierpont Morgan

A financial panic in 1893 caused one-quarter of all railroads into bankruptcy. Bankers led by JP Morgan quickly bought and took control of the vankrupts railroads and consolidated them. With competition eliminated, he could stabilize rates and reduce the debt. By 1900, seven giant systems controlled nearly 2/3rds of the nation’s railroads, the consolidation made the rail system more efficient but was controlled only by a few powerful men such as Morgon who dominated the boards for competing railroad corps through interlocking directorates (same directors ran competing companies). They were able to create regional railroad monopolies. In the late 19th century, local, state, and federal governments invested in the development of railroads. However, at the same time, customers and small investors often felt victims for slick financial schemes and ruthless practices. early attempt to regulate railroads by law didn’t work, the Granger laws passed in Midwestern states in the 1870s were overturned and the federal Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 was at first ineffective. It won’t be until the early 1900s that Congress expand the powers of the Interstate Commerce Commission to protect the public.

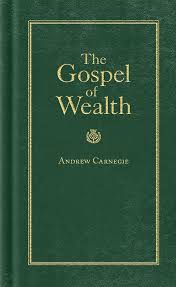

Andrew Carnegie

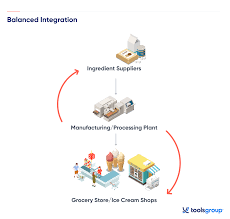

The late 19th century had a major shift in the nature of industry. Early factories had focused on making textiles, clothing, and leather products. After the Civil War, a second wave of industry (often called the “Second Industrial Revolution) took over causing the growth of a large-scale industry. During this era, steel, petroleum, electricity, and industrial machinery were the main industry producers. Leadership of the rapidly growing steel industry was took over by Andrew Carnegie. Andrew was born in Scotland in 1835, immigrated to the Us and worked his way up from poverty to become a superintendent of a Pennsylvania Railroad. In the 1870s, he started manufacturing steel in Pittsburgh and soon outlapped his competitors by combining salesmanship and use of the latest technology. Carnegie employed a business strategy known as vertical integration, where a company would control every stage of the industrial process, mining the raw material to transport the finished product. By 1900, Carnegie Steel employed 20,00 workers and produced more steel than all the mills in Britain. He decided to retire later on in his life and devote himself to philanthropy. Carnegie sold his company in 1900 for more than $400 million to a new combination led by Morgan. The new corporation, United States Steel, was the first billion-dollar company. It was the largest enterprise in the world, employing 168,000 people and controlling more than 3/5ths of the nation’s steel business.

United States Steel

He decided to retire later on in his life and devote himself to philanthropy. Carnegie sold his company in 1900 for more than $400 million to a new combination led by Morgan. The new corporation, United States Steel, was the first billion-dollar company. It was the largest enterprise in the world, employing 168,000 people and controlling more than 3/5ths of the nation’s steel business.

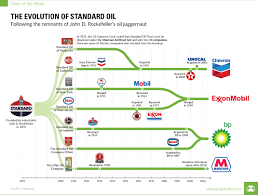

John D. Rockefeller

The first US oil well was drilled by Edwin Drake in 1859 in Pennsylvania. Four years later, 1863, a young John D Rockefeller’s founded a company that would quickly eliminate its competition and took control of most of the nation’s oil refineries. By 1881, his company, known as the Standard Oil Trust, controlled 90% of the oil refinery business. It had become a monopoly, where a company dominates a markets so much that it faces little to no competition. By controlling the supply and prices of oil, Standard Oil’s profits soared and so did Rockefeller’s fortune. When he retired, his fortune was worth around $900 million. Standard Oil grew due to applying new tech and efficient management practices. Even though it sometimes kept prices lower for consumers, the company gew it became very powerful. Rockefellers was able to extort rebate from railroad companies and temporarily cut prices in order to force rival companies to sell out.

Standard Oil

The first US oil well was drilled by Edwin Drake in 1859 in Pennsylvania. Four years later, 1863, a young John D Rockefeller’s founded a company that would quickly eliminate its competition and took control of most of the nation’s oil refineries. By 1881, his company, known as the Standard Oil Trust, controlled 90% of the oil refinery business. It had become a monopoly, where a company dominates a markets so much that it faces little to no competition. By controlling the supply and prices of oil, Standard Oil’s profits soared and so did Rockefeller’s fortune. When he retired, his fortune was worth around $900 million. Standard Oil grew due to applying new tech and efficient management practices. Even though it sometimes kept prices lower for consumers, the company gew it became very powerful. Rockefellers was able to extort rebate from railroad companies and temporarily cut prices in order to force rival companies to sell out.

Horizontal integration

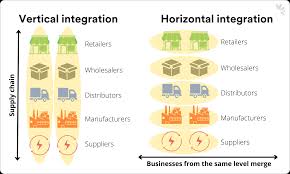

Emulating the success of Rockefellers, Carnegie, and Morgan, industry leaders in the meat, sugar, tobacco, and other industries also formed huge companies to gain control of the markets. The companies were organized in various ways:

A trust is an organization or board that manages the assets of multiple companies. For example, under Rockefellers, Standard Oil became a trust in which one board of trustees managed a combination of once-competing oil companies

Horizontal integration is a process through which one company takes control of all its competition in a market, for example in oil refining or coal mining

Vertical Integration is a process where a company takes control of all of the steps below them to make their product. For example, Carnegie Steel controlled coal mines, ore ships, steel mills, and distribution systems for the steel company to reduce their own costs and improve efficiency resulting in more profit

Holding Company is a company that is created to own and control companies in different industries. Banker J Pierpont Morgan managed a holding company that owned various companies in several businesses such as banking, rail, and steel.

Critics often argue that these giant corporations are bad for the economy. By creating monopolies, they reduced competition in the open and free markets. Monopolies, also in their views, slow innovation, overcharge consumers, and develop huge amounts of political influence. The word “monopoly” came to be known as a giant company that became so large that it was a threat to the public interest.

vertical integration

Emulating the success of Rockefellers, Carnegie, and Morgan, industry leaders in the meat, sugar, tobacco, and other industries also formed huge companies to gain control of the markets. The companies were organized in various ways:

Vertical Integration is a process where a company takes control of all of the steps below them to make their product. For example, Carnegie Steel controlled coal mines, ore ships, steel mills, and distribution systems for the steel company to reduce their own costs and improve efficiency resulting in more profit

Holding Company is a company that is created to own and control companies in different industries. Banker J Pierpont Morgan managed a holding company that owned various companies in several businesses such as banking, rail, and steel.

Critics often argue that these giant corporations are bad for the economy. By creating monopolies, they reduced competition in the open and free markets. Monopolies, also in their views, slow innovation, overcharge consumers, and develop huge amounts of political influence. The word “monopoly” came to be known as a giant company that became so large that it was a threat to the public interest.

holding company

Emulating the success of Rockefellers, Carnegie, and Morgan, industry leaders in the meat, sugar, tobacco, and other industries also formed huge companies to gain control of the markets. The companies were organized in various ways:

Vertical Integration is a process where a company takes control of all of the steps below them to make their product. For example, Carnegie Steel controlled coal mines, ore ships, steel mills, and distribution systems for the steel company to reduce their own costs and improve efficiency resulting in more profit

Holding Company is a company that is created to own and control companies in different industries. Banker J Pierpont Morgan managed a holding company that owned various companies in several businesses such as banking, rail, and steel.

Critics often argue that these giant corporations are bad for the economy. By creating monopolies, they reduced competition in the open and free markets. Monopolies, also in their views, slow innovation, overcharge consumers, and develop huge amounts of political influence. The word “monopoly” came to be known as a giant company that became so large that it was a threat to the public interest.

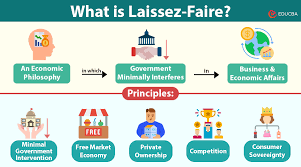

laissez-faire

Federal, state, and even local governments supported businesses and economic growth through passing high tariffs, building infrastructure, and operating public schools and universities. However, the economic, scientific, and religious beliefs of the time led people to not regulate businesses. The economic expression of these beliefs was summed up in the French phrase “laissez-faire”.

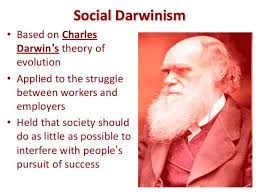

social Darwinism

In 1776, an economist named Adam Smith argued in his paper The Wealth of Nations that Mercantilism was less efficient than allowing businesses to naturally grow through the “invisible hand” of the law of supply and demand. While Smith agreed that there should be some government regulation, he believed that unregulated businesses would be motivated by their own self-interest to offer improved goods and services at lower prices. In the 19th century, American capitalists and industrialists used the laissez-faire theory to justify their way of gaining wealth. The rise of monopolies in the 1880s seemed to undercut the competition needed for natural regulation. Laissez-faire theory would be constantly used in the Congress and lobbies to ward off any threat of government regulation. Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection in biology created controversy with religious conservatives, but used by conservative economists. Herbert Spencer, an English social philosophers, argued for Social Darwinism which was the idea that Darwin’s theories about natural selection and the survival of the fittest should be used in the marketplace. Spencer believed that giving wealth and power only to the elite would benefit everyone (would call them “fit”). A student of Spencer’s beliefs, William Graham Sumner of Yale, introduced the ideas of Social Darwinism to sociology in the US, arguing that helping the poor was misguided because it interfered with the laws of nature and only weakened the evolution of the species. The teachings of respected scholars like Sumner provided the “scientific” reasoning for racial intolerance. Race theories around the superiority of groups of others would spill over to the 1900s.

survival of the fittest

Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection in biology created controversy with religious conservatives, but used by conservative economists. Herbert Spencer, an English social philosophers, argued for Social Darwinism which was the idea that Darwin’s theories about natural selection and the survival of the fittest should be used in the marketplace. Spencer believed that giving wealth and power only to the elite would benefit everyone (would call them “fit”). A student of Spencer’s beliefs, William Graham Sumner of Yale, introduced the ideas of Social Darwinism to sociology in the US, arguing that helping the poor was misguided because it interfered with the laws of nature and only weakened the evolution of the species. The teachings of respected scholars like Sumner provided the “scientific” reasoning for racial intolerance. Race theories around the superiority of groups of others would spill over to the 1900s.

Protestant work ethic

More Americans instead found religious beliefs as a way to justify the wealth and power of the industrialists and bankers of the time. John D Rockefeller applied the Protestant Work Ethic (that material success was a sign that God favored you and wanted to reward you) to both his own personal life and business. He can then say that “God gave me my riches”. In a popular lecture of the time, “Acres of Diamonds”, a reverend by the name of Russel Cornwell preached that everyone had a duty to become rich. By the 1890s, the richest 10% of the US controlled 90% of the nation’s wealth. Industrialization created a new class of millionaires who would splurge on their wealth with lavish parties and mansions. Many Americans ignored the increasing gaps of the poor and rich. They would instead focus on “self-made men” in businesses such as Andrew Carnegie and Thomas Edison. However, opportunities for upward mobility did exist but only, statistically, for Anglo-Saxon, white, Protestant males from upper or middle class backgrounds whose father was in business or banking. Corporations in the late 19th century wanted to do business more internationally, such as Asia and Latin America. Industries wanted raw materials to process finished goods. Around 1900, imports from Cuba, Brazil, and Asia of sugar and rubber was 30% of the US’s imports. Businesses also wanted to sell finished products internationally, as well. Around the same time, the US only accounted for 5% of the world’s population but 15% of global exports. The growth of business and their interest’s abroad was one reason why the US became more involved in the international affairs in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

collective bargaining

The growth of industry during this time was based on hard physical labor like in mines or factories. For the people doing these jobs, life was hard. By 1900, 2/3rds of all employed people in the US worked for wages, usually jobs that required ten hours a day, six days a week. Wages were determined by the economic principle of supply and demand, and since there was a massive amount of immigration in the US, wages were kept at a level barely liveable. However, these low wages would be justified by people like David Ricardo, who argued his famous “iron law of wages” that raising wages would increase the amount of people working, thereby naturally causing wages to lower and creating an endless cycle of misery and starvation. Real wages rose steadily in the late 19th century, however most people living on wages couldn’t survive with one income source. So instead, working-class families needed the income of both women and children. In 1870, about 12% of the country’s children were employed, by 1900 that number increased to 20%. In 1890, 11 million for the 12.5 million families in the US averaged less than $380 a year. Before the industrial revolution, workers worked in small workshops that focused on artisan skills. People would often feel accomplished for completing their work. Factory work was totally different, workers were often assigned just one step in the processes, performed semiskilled tasks monotonously. Both immigrants and rural migrants had to learn to work under the clock, and in many industries such as railroads and mining the working conditions were dangerous. Many workers were exposed to chemicals and pollutants that were only later discovered to cause illnesses and early death. Industrial workers rebelled against intolerable working conditions by missing work or quitting. They often changed jobs, often every 3 years. About 20% of the industrial workers dropped out of the industrial workplace, which was higher than people who joined labor unions. During the late 19th century, the country witnessed the most deadly and frequent labor conflicts in its history. Many feared for open conflict between the working class and elite. With a surplus of low-cost labor, management held most of the power in the struggles against organized labor. Strikes could easily go away by bringing in strike breakers or scabs who are unemployed people looking jobs (replacing them). They also used lockouts (act of closing a factory before organization occured), blacklist (names of pro-union workers that employers circulated to prevent them from getting jobs again), yellow-dog contract (contract that doesn’t allow you to join a union), private guards and state militia (used by employers to put down strikes), and Court injunctions (judicial action to prevent a strike). Management would also foster publice fear of unions by presenting them as anarchistic and un-American. Before 1900, management won most battles since if violence did occur, they could bring in federal and state governments to help. Workers were divided on the best methods for defending themselves against management. Some Union leaders wanted political action, other wanted direct confrontation such as strikes, picketing, boycotts, and slowdowns in order to achieve Union recognition as well as collective bargaining. Collective bargaining is the ability of workers to negotiate as group with employers about conditions and wages.

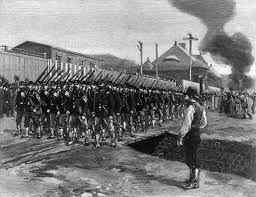

Railroad strike of 1877

One of the worst outbreaks of Labor violence happened in 1877. During an economic depression, the railroad companies cut wages in order to reduce their costs. A strike on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad quickly spread across 11 states and caused 2/3rds of the country’s rail lines to be shut down. Railroad workers were then further assisted by 500,000 workers from other industries in an increasingly escalating strike that rapidly became national. For the first time since 1830s, president Rutherford B Hayes used federal troops to end a labor dispute. The strike and violence ended, but more than 100 people would lose their lives. After the strike, some employers addressed the issues by improving wages and conditions, while others doubled-down and became harsher against Unions.

National Labor Union

Before the 1860s, Unions were originally organized as local associations in a city or region, usually craft unions which focused on one type of work. The first attempt to organize all workers, regardless of job, was the National Labor Union. Founded in 1866, it had around 640,000 members by 1868. they championed the goals of higher wages, 8 hour work day, and other social programs such as equal rights for both women and African Americans, monetary reform, and worker cooperatives. Its chief victory was winning the 8 hour work day for federal government workers, but lost support after a depression in 1873 and an unsuccessful strike in 1877.

Knights of Labor

A second national Labor Union began in 1869 as a secret society to avoid detection by employers, known as the Knights of Labor. Under the leadership of Terence V. Powderly, the Union went public in 1881, opening its membership to all workers including African Americans and women. Powdelry pushed for reforms such as a forming worker cooperative, abolishing child labor, abolishing trusts and monopolies and settling labor dispute by arbitration than strikes. However, because the Knights were loosely organized, Powderly couldn’t control local units that decided to strike. The Knights of Labor grew tremendously, having a peak membership of 730,000 members in 1886. However, public opinion after the 1886 Haymarket bombing turned against them and caused membership to decline.

Haymarket bombing

Chicago, with around 80,000 Knights in 86, was the site of the first May Day labor movement. Living in Chicago were also 200 anarchists who wanted a violent overthrow of all government. In response to the May Day movement calling for a general strike to get an eight hour work day, laborers became violent at Chicago’s McCormick Harvester plant. On May 4, workers held a public meeting in Haymarket Square. Police attempted to break up the meeting, but someone threw a bomb which killed seven police officers. The bomb thrower was never found, but anarchist leaders were tired from the crime and seven were sentenced to death. Many American, horrified by the bomb incident, viewed Unions as radical and violent. The Knights of Labor, the most prominent labor Union at the time, lost popularity and therefore membership.

American Federation of Labor (AFL)

The American Federation of Labor focused on more narrower economic goals. Created in 1886 as a combination of 25 craft unions for skilled workers, the AFL focused on higher wages and improving worker conditions led by Samuel Gompers until 1924. Gompers told his local unions to strike until his employer agreed to negotiate a new contract through collective bargaining. By 1901, the AFL was the nation’s largest labor organization with 1 million members. However, this Union would not achieve any major achievements until the early decades of the 1900s.

Samuel Gompers

The American Federation of Labor focused on more narrower economic goals. Created in 1886 as a combination of 25 craft unions for skilled workers, the AFL focused on higher wages and improving worker conditions led by Samuel Gompers until 1924. Gompers told his local unions to strike until his employer agreed to negotiate a new contract through collective bargaining. By 1901, the AFL was the nation’s largest labor organization with 1 million members. However, this Union would not achieve any major achievements until the early decades of the 1900s.

Homestead strike

Two massive strikes in the last decade of the 1800s showed the growing discontent of labors as well as the power of management. Henry Clay Frick, a manager of Andrew Carnegie’s homestead Steel plant around Pittsburgh, caused a strike when he cut wages by around 20% in 1892. Frick used a lockout, private guards, and strikebreakers to defeat the workers after 5 months of striking. 16 people died and the failure of the Homestead strike set back the Union movement in the steel industry until the New Deal in the 1930s.

Pullman strike

Another alarming strike for conservatives was a strike by workers in George Pullman’s company near Chicago. The Pullman Palace Car Company manufactured railroad sleeping car and in 1894 Pullman announced a general cut in wages and fired the leaders of a workers delegation. The workers at Pullman laid down their tools and asked for help from the American Railroad Union. The ARU leader, Eugene V Debs, told railroad workers not to handle any trains with Pullman cars. The boycott caused major tie ups in transportation across the country. Railroad owners decided to support Pullman by linking Pullman car to mail trains, which allowed them to appeal President Grover Cleveland to use the army to keep the mail trains running. A federal court issued an injunction to forbid interference with mail cars and ordered railroad workers to abandon the boycott. For failing to respond to this, Debs and other Union leaders were arrested and jailed. The jailed effectively ended the strike, and in the case for In re Debs (1895), the Supreme Court approved the usage of Court injunctions against strikes, which gave employers another power legal weapon against Unions.

Eugene v. Debs

Another alarming strike for conservatives was a strike by workers in George Pullman’s company near Chicago. The Pullman Palace Car Company manufactured railroad sleeping car and in 1894 Pullman announced a general cut in wages and fired the leaders of a workers delegation. The workers at Pullman laid down their tools and asked for help from the American Railroad Union. The ARU leader, Eugene V Debs, told railroad workers not to handle any trains with Pullman cars. The boycott caused major tie ups in transportation across the country. Railroad owners decided to support Pullman by linking Pullman car to mail trains, which allowed them to appeal President Grover Cleveland to use the army to keep the mail trains running. A federal court issued an injunction to forbid interference with mail cars and ordered railroad workers to abandon the boycott. For failing to respond to this, Debs and other Union leaders were arrested and jailed. The jailed effectively ended the strike, and in the case for In re Debs (1895), the Supreme Court approved the usage of Court injunctions against strikes, which gave employers another power legal weapon against Unions. By 1900, only 3% of American workers belonged to Unions. Management often times had the upper hand, alongside government support usually. But, people started to realize the need for better balance. During the Gilded Age, industrial growth was focused in the Northeast and Midwest, the parts of the country with the largest population, capital, and best transportation. As industries grew, These regions created more cities and attracted even more people.

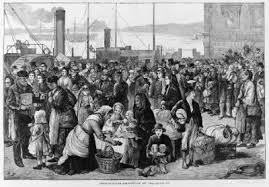

“old” immigrants

In 1893, more than 12 million people attended the Chicago World’s Fair (World’s Columbian Exposition). Chicago’s population had grown from a small town of 4,000 to the second largest city in the country with more than 1 million residents, fastest growing city in that nation if not the world. However, visitors often were complaining about the different languages spoken since more than 3/4ths of the population were either foreign-born or children of foreign-born. In the last half of the 19th century, the US pop more than tripled from 23.2 million in 1850 to 76.2 million in 1900. 16.2 million helped provide this growth, alongside another 8.8 million in the peak years of immigration (1901-10). A number of pushes and pulls in the world created the dramatic increase of immigration:

The poverty of displaced farmers from political turmoil or mechanization

Overpopulation and joblessness in Europeans cities

Religious persecution, specifically Jewish people in Eastern Europe

Positive reasons for moving to the US included the religious and political freedom as well as the economic opportunity from the West and industrial jobs. Economic opportunity fluctuated with the economy, meaning that times of prosperity meant an increase in immigration. Not only that but the introduction of large steamships that offered low cost one-way tickets in the ships’ steerage made it possible for millions of poor people to physically move to the US. Through the 1880s, most immigrants came from Western and Northern Europe: British isles, Germany, and Scandinavia. Most of the “old immigrants” were Protestants and mostly spoke English, alongside having high levels of literacy and skills which made them easily blend into rural American society. But, Irish and German Catholics would face heavy discrimination.