PSYC 309: Final

1/91

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

92 Terms

what did Jim do while talking to Dwight that depicts how much we value eye direction when in a conversation?

Jim kept staring at Dwight’s forehead and pretended like he wasn’t doing anything weird - Dwight got mad and couldn’t figure out what Jim was trying to do

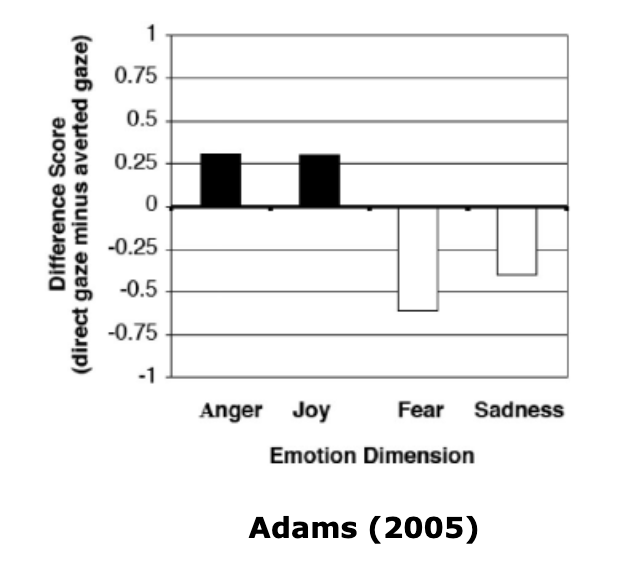

BACKGROUND: does our gaze affect how we perceive emotion? (Adams & Kleck, 2005)

approach-oriented emotions (joy, love, anger) expressed with direct gaze

avoidance-oriented emotions (embarrassment, sorrow, disgust) expressed with averted gaze

direct gaze → dominance displays

averted gaze → submission displays

how motivational tendencies depicted through emotion and gaze are perceived by an observer has not been studied before

HYPOTHESES: does our gaze affect how we perceive emotion? (Adams & Kleck, 2005)

congruence of gaze and emotion cues in facial displays would likely enhance emotion perception

direct gaze = increase of approach-oriented emotion perception (joy, anger)

averted gaze = increase of avoidance-oriented emotion perception (fear, sadness)

shared-signal hypothesis (Adams & Kleck, 2005)

signal value (if one should approach or avoid) is determined when two expression modalities match - both together increase perception of the underlying emotion communicated by the face

gaze direction

bodily expression

facial expression

STUDIES: does our gaze affect how we perceive emotion? (Adams & Kleck, 2005)

Examined effects of gaze direction on perception of emotional traits attributed to neutral facial expressions

gaze direction on perception of ambiguous facial expressions

differences in perceived emotional intensity in unambiguous facial expressions

RESULTS: does our gaze affect how we perceive emotion? (Adams & Kleck, 2005)

intensity of approach-oriented emotions (joy, anger) attributed to direct gazes, intensity of avoidance-oriented (sadness, fear) emotions attributed to averted gazes - gaze important influence

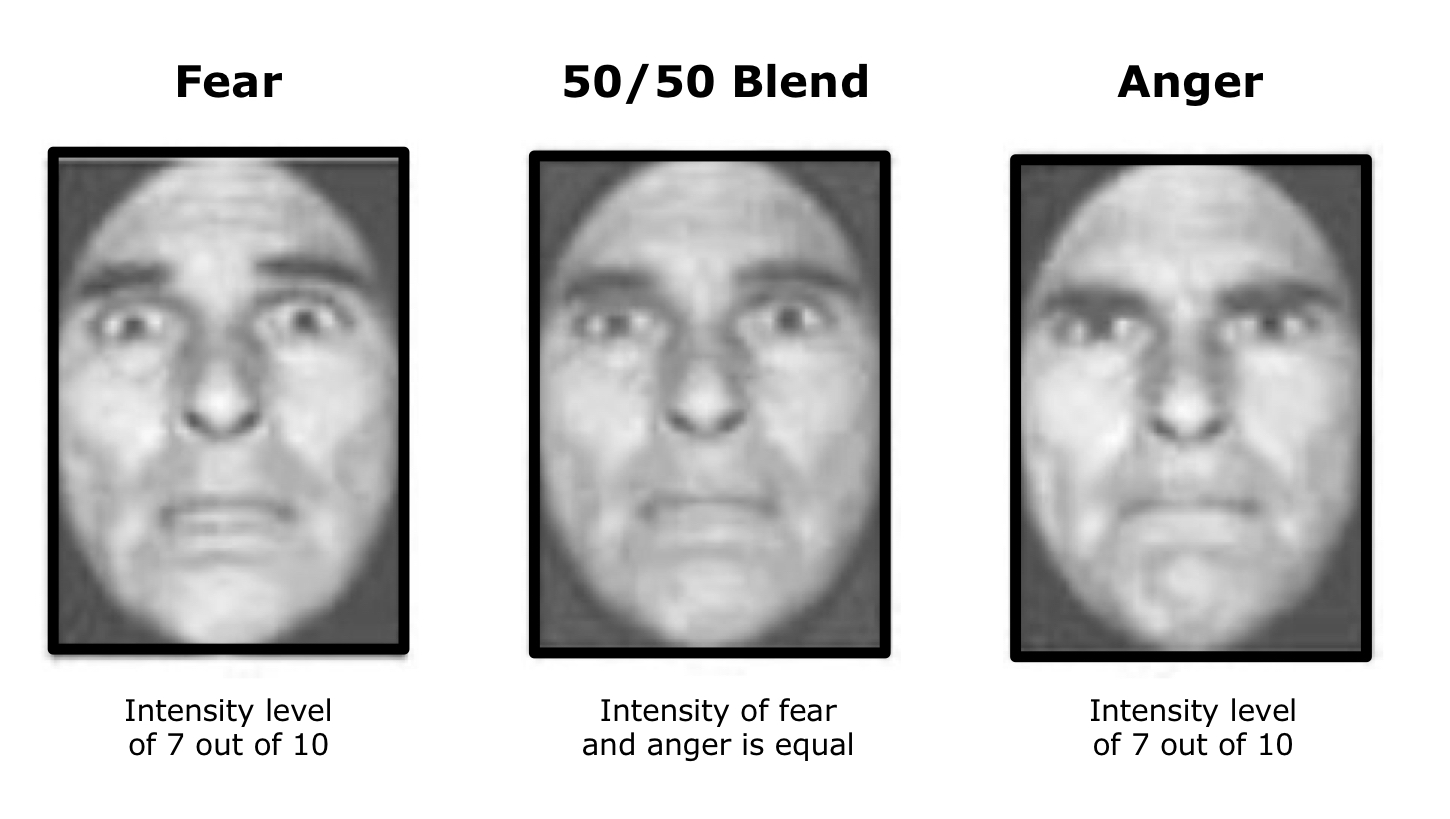

anger/fear blends with direct gaze equally likely to be labeled as fearful/angry, while for the same blend with averted gaze, fear labelling is much more intense - fear must be physically more intense than anger expressions

direct gaze enhanced perceived intensity of joy and anger, averted gaze enhances perceived intensity of fear and sadness

gaze influencing emotion perception actually depends on specific type of emotion in question - for some emotions, averted gaze enhances perception of the emotion and removes ambiguity

DISCUSSION: does our gaze affect how we perceive emotion? (Adams & Kleck, 2005)

emotional expression and gaze communicate whether to approach or avoid → when congruent in signal value, gaze enhances the perception of emotion

approach-oriented emotions and direct eye-contact are associated with perceptions of social dominance → incongruent combinations of these two would cause confusion and fear/sadness are more ambiguous because they are not dominant emotions

gaze could influence anger and fear because it indicates the source of a threat - averted gaze crucial to fear expressions may enhance the perception of fear because it helps indicate source of potential threat

gaze may make more conspicuous emotional cues in the face OR could just be a fundamental part of certain facial expression

FURTHER RESEARCH: does our gaze affect how we perceive emotion? (Adams & Kleck, 2005)

Is gaze considered a fundamental part of cues in emotion communication, or does it inform more general decision making process, or does it act as a separate cue that interacts with facial expression?

QUESTIONS: Shared Signal Hypothesis: Facial and Bodily Expressions of Emotion Mutually Inform one Another (Albohn et al., 2022)

Do faces facilitate the recognition of bodily emotion?

Do bodies facilitate the recognition of facial emotion?

(mutual processing)

STUDIES: Shared Signal Hypothesis: Facial and Bodily Expressions of Emotion Mutually Inform one Another (Albohn et al., 2022)

Ps identified a face as fearful or angry, while body expression was subliminally represented

Ps identified a body as fearful or angry, while facial expression was subliminally represented

Intensity of subliminal emotion varied; whether the two stimuli (face and body) were the same or different emotion varied

RESULTS: Shared Signal Hypothesis: Facial and Bodily Expressions of Emotion Mutually Inform one Another (Albohn et al., 2022)

both studies revealed that integration of body and face cues had strong support while interferences did not - most pronounced for low-emotional clarity facial and body expression instead of intense clarity individual face and body expression

when more info is needed in one channel, the other channel is recruited to disentangle ambiguities

integration effects were moderated by the emotional clarity of the subliminal stimuli - ambiguity plays a role in what cues should be visually integrated

face and body emotion are influenced by context

DISCUSSION: Shared Signal Hypothesis: Facial and Bodily Expressions of Emotion Mutually Inform one Another (Albohn et al., 2022)

We tend to integrate channels of emotional information more when there is congruency between both emotional channels - people have higher accuracy when recognizing congruent pairings of faces and bodies

Significant evidence for integration improving emotion accuracy, but none for interference

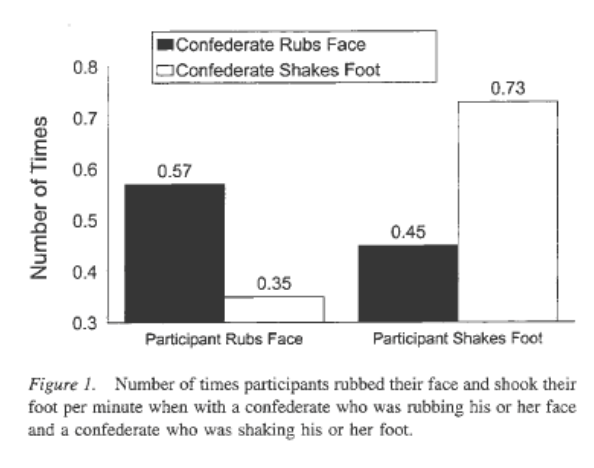

non-conscious mimicry (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999)

found that when participants were talking to a confederate that rubbed their face or shook their foot (between-groups) they too did what their confederate did more, but not the behaviour their confederate was not doing

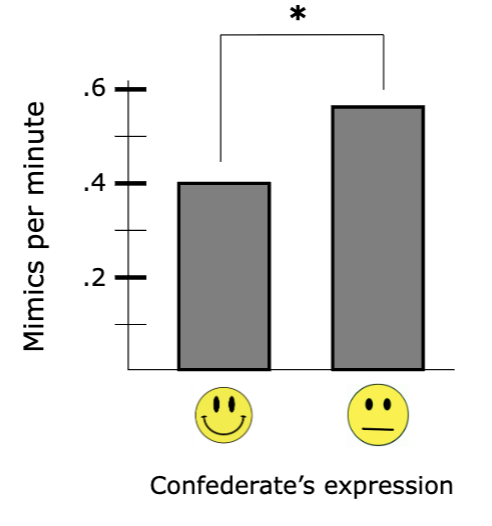

nonconscious mimicry of bodily expression depending on the facial expression of the conversation partner (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999)

participants mimicked their partner’s bodily expression more when they were not smiling than when they were smiling

Why do we mimic people more when they aren’t smiling at us? What does this tell us about the role of mimicry in social interactions? (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999)

we mimic less when a person is already smiling because it seems like they already like us and we don’t need to exaggerate our appearance as a friendly/approachable person

not smiling signals to us that something is wrong - it is an adaptive mechanism for us to mimic our conversation partner to facilitate a positive environment

Mimicry can increase liking for the conversation partner and makes the interactions more smooth

Mimicry can facilitate effective communication and behaviour coordination in groups

perception-behaviour link

merely perceiving an action performed by another can lead one to perform that action

facilitates mimicry and empathetic understanding within social interactions

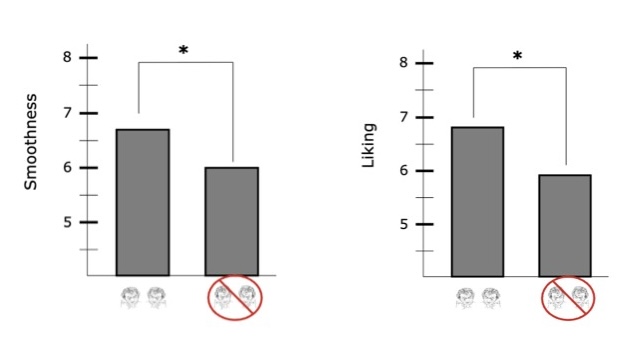

how does mimicry affect the perception and likability of a conversation partner? (Chartrand & Bargh, 1999)

Ps were paired with a conversation partner (confederate) that either mimicked them OR did not mimic them → Ps then rated how much they liked the confederate and how smooth the interaction felt

found that mimicry facilitated higher likability and smoothness of interaction that no mimicry in a conversation

why does Michael like Andy so much when he first meets him?

Andy is purposefully mimicking his personality and sometimes saying the things Michael says back to him - Michael immediately really likes him

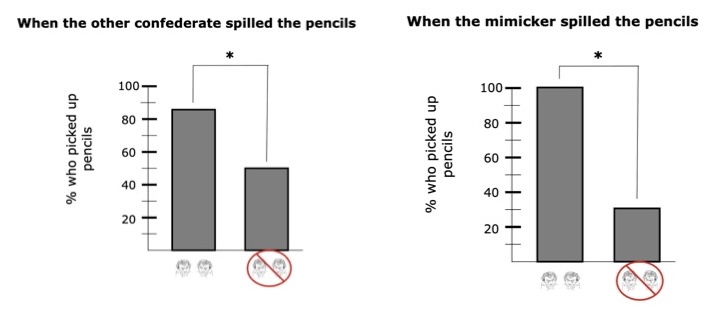

Do the positive social impacts of mimicry extend beyond just the person who mimics us? Does mimicry promote prosocial behaviour? (Van Baaren et al., 2004)

Ps were either mimicked by a confederate or not mimicked → their confederate that mimicked or did not mimic them then spills a cup of pencils OR a second confederate who never mimicked the Ps spill a cup of pencils

more Ps picked up the pencils their mimicker spilled (100%) than their non-mimicker (33%)

more Ps that had been mimicked picked up the pencils spilled by the other confederate (84%) than the Ps that hadn’t been mimicked (48%)

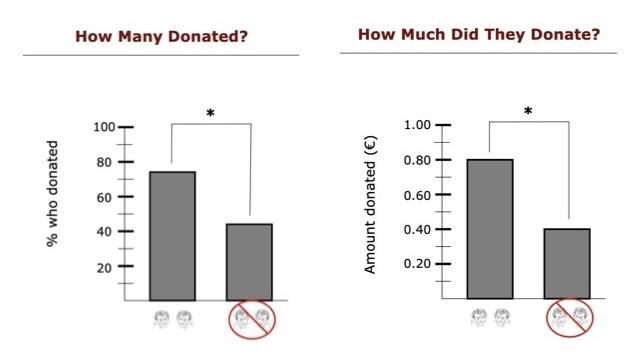

can pro-sociality due to mimicry be replicated to other situations outside of the pencil dropping confederates? (Van Baaren et al., 2004)

Ps talked to a confederate that mimicked them OR a confederate that did not mimic them - Ps were then given money for their participation. They were told they could donate it to a (fake) charity if they wanted before the RA left them to complete a post-survey

Ps that were mimicked were more likely to donate and to donate more

Mimicry generalizes to other scenarios

what is the basis for mimicry?

mirror neurons - neurons specialized for imitation

mirror neurons

discovered by Giacomo Rizzolatti

develop with our motor system - also found in primary somatosensory cortex, parietal cortex

copying, mirroring, imitating system → empathy (how we would feel if bad things were “mirrored” onto us)

can learn because of them - understand the actions and intentions of other people

theory of mind

when they are damaged, people don’t understand other people’s actions → Autism, other brain damage disorders

their main differentiating factor is their response patterns

2 kinds of facial mimicry

automatic - unconsciously make face in response to someone’s face

voluntary - consciously copy someone else’s face

benefits of automatic facial mimicry

facilitates social interaction - interpersonal rapport, emotional contagion, emotion recognition

BACKGROUND: how do deficits in automatic mimicry contribute to social challenges characteristic of autism? (McIntosh, 2006)

mimicry deficits in childhood could impair child’s ability to grasp others’ emotions and form self-other correspondences → related to autism

automatic mimicry facilitates social interaction and voluntary mimicry is effortful and sensitive to situational demands → autism is related to automatic deficits, resulting in reliance on voluntary mimicry

ASD people express a full range of emotions, show attachment, and comprehend emotional situations - deficits in automatic processes

STUDY: how do deficits in automatic mimicry contribute to social challenges characteristic of autism? (McIntosh, 2006)

14 high functioning adolescents and adults with ASD and 14 controls - Ps watched pictures as they appeared on screen (automatic) and then were asked to make an expression just like the one on the screen (voluntary)

RESULTS: how do deficits in automatic mimicry contribute to social challenges characteristic of autism? (McIntosh, 2006)

Anger and happiness have unique EMG (electromyography) patterns - monitors electrical changes in muscle activity over cheek and brow region

automatic condition: typical group had more congruent responses (68%) than incongruent (29%), ASD group had 36% congruent responses and (50%) [RESULTS WEREN’T SIG]

voluntary condition: typical group (100% congruent, 17% incongruent) had similar responses to ASD group (96% congruent, 21% incongruent)

![<ul><li><p>Anger and happiness have unique EMG (electromyography) patterns - monitors electrical changes in muscle activity over cheek and brow region</p></li><li><p>automatic condition: typical group had more congruent responses (68%) than incongruent (29%), ASD group had 36% congruent responses and (50%) [RESULTS WEREN’T SIG]</p></li><li><p>voluntary condition: typical group (100% congruent, 17% incongruent) had similar responses to ASD group (96% congruent, 21% incongruent)</p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/1ce160e1-ec81-40f8-897d-c857cad5d9fa.jpg)

DISCUSSION: how do deficits in automatic mimicry contribute to social challenges characteristic of autism? (McIntosh, 2006)

suggests that ASD people’s absence of automatic mimicry was not due to deficits in perception, praxis, motivation or tasks understanding since they performed normally on voluntary

showed the same rate of responding to faces automatically, but struggled with discriminating between happy or angry

possibly amygdala abnormalities

support the idea of emotion deficit in autism

how is mentalizing depicted in the scene with Lafawnduh and Kip in Napoleon Dynamite?

neither of them speak, but we can still read their thoughts through other cues - their facial expression, actions

Kip shows through his face that he is unsure about being gifted a chain to wear, but Lafawnduh gives him a reassuring look

mentalizing

thinking about how other people think

common social device identifying awareness is sarcasm

different from recognizing emotions

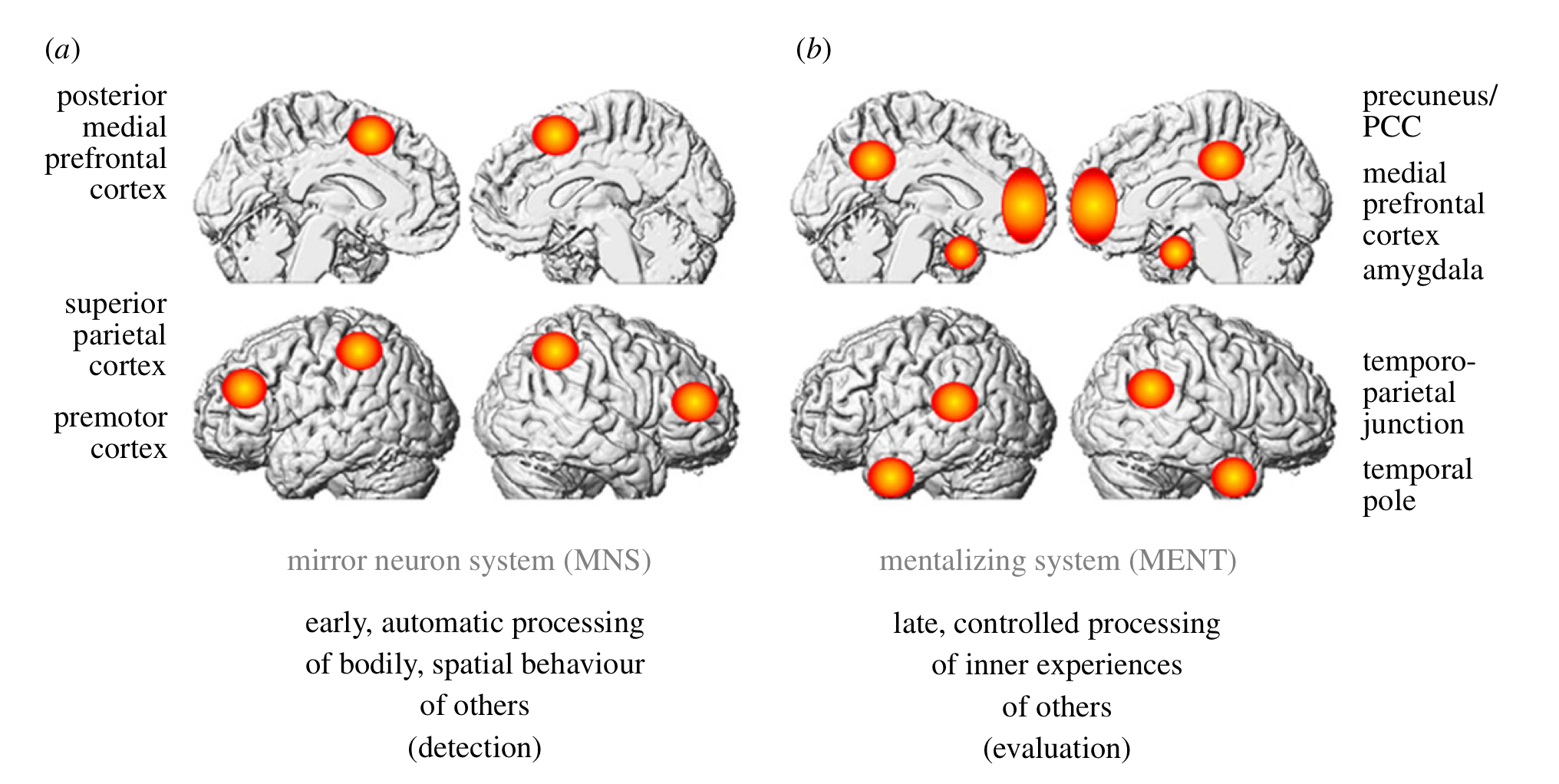

two social brains - mimicry (mirror neuron) and mentalizing systems

mimicry/mirror neuron system serves early stages of social info processing - spatial or bodily signals

mentalizing/theory of mind neuron system serves late stages of social info processing - evaluation of emotional and psychological states of others

both interact with each other

mirror neuron neural system

rapid, automatic processing of face, body language and behaviour of others - social detection

premotor cortex, primary somatosensory cortex, inferior parietal cortex

mentalizing neural system

slower, controlled processing of the thoughts, feelings and inner experiences of other - social evaluation

prefrontal cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, temporo-parietal junction, temporal pole, posterior parietal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex

BACKGROUND: mentalizing in people with neurodegenerative disorders (Huntington’s Disease) (Larsen et al., 2016)

there is impaired recognition of facial expressions of all negative emotions in people with manifest HD - inconsistent in people with premanifest HD but may be seen in all negative emotions

manifest HD associated with difficulty in tasks that require interpretation of social situations and attribution of mental states to others

huntington’s disease

rare, inherited neurodegenerative disorder that typically begins to manifest between 30 to 50 years

earliest symptoms include disruptions in emotion recognition associated with mirror neuron system

associated with personality changes and breakdown of interpersonal relationships

STUDY: mentalizing in people with neurodegenerative disorders (Huntington’s Disease) (Larsen et al., 2016)

3 groups: (1) individuals with Huntington’s gene and manifesting clinical symptoms (manifest), (2) individuals with Huntington’s gene and manifesting non-clinical symptoms (pre-manifest), (3) individuals with Huntington’s gene in family, but nor carrying the gene

given a variety of tasks (also emotion evaluation task)

emotion hexagon: asked to say which emotion best describes morphed facial expressions of happiness, surprise, fear, sadness, anger, and disgust (emotional recognition test)

RME test: asked to pick the word that best described what they eyes were expressing - need to attribute mental states to them, aka theory of mind

sarcasm task: short scenes with actors having either a sarcastic or sincere (neutral) exchange - Ps asked a factual question (assessing story comprehension) and an attitude question (assessing comprehension of speaker’s true meaning

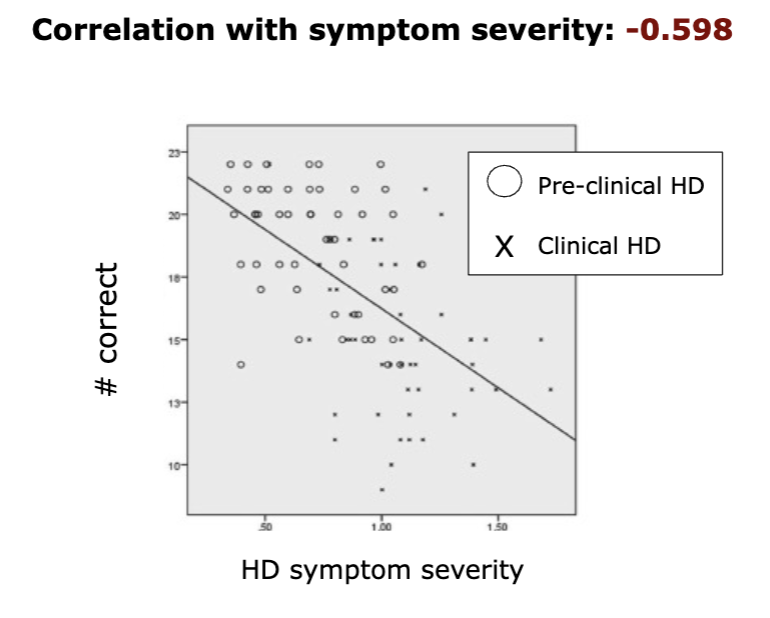

EMOTION RECOGNITION RESULTS: mentalizing in people with neurodegenerative disorders (Huntington’s Disease) (Larsen et al., 2016)

the number of correct emotions recognized went down as severity in Huntington’s Disease went up

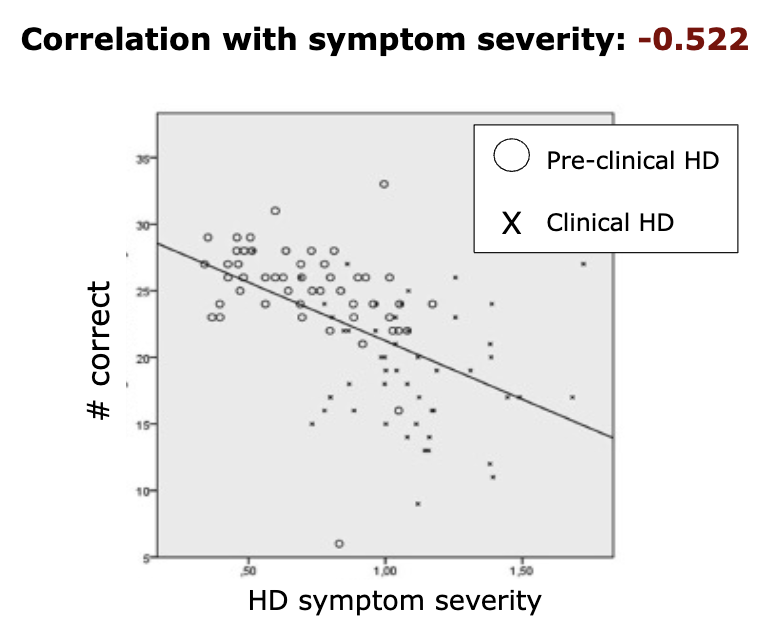

EYE LABELING RESULTS: mentalizing in people with neurodegenerative disorders (Huntington’s Disease) (Larsen et al., 2016)

the number of eyes labeled correctly went down as Huntington’s Disease symptom severity went up

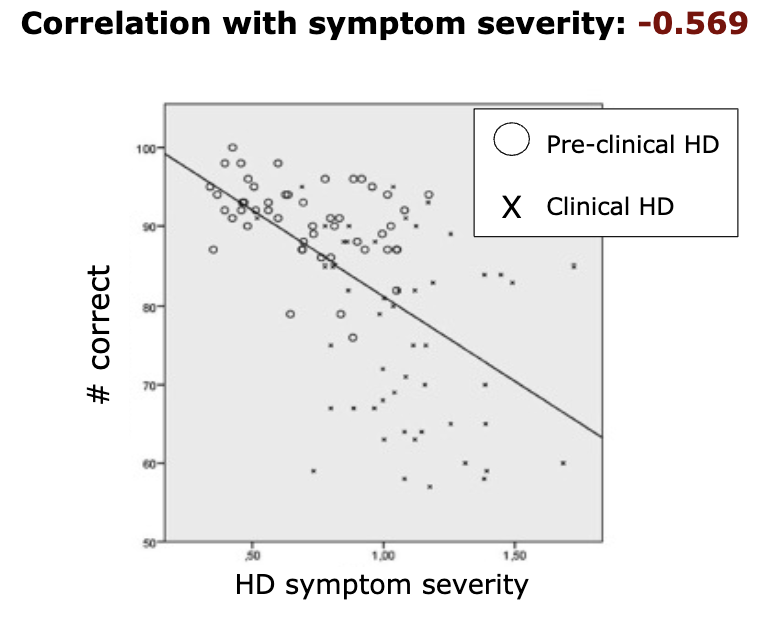

SARCASM IDENTIFICATION RESULTS: mentalizing in people with neurodegenerative disorders (Huntington’s Disease) (Larsen et al., 2016)

successful identification of sarcasm went down as Huntington’s disease symptom severity increased

What does sarcasm reveal about social cognition?

sarcasm relies on the ability to mentalize

Involves reading nonverbal cues like facial expression, body language, eye direction

reveals individual’s ability to navigate complex social hierarchies

regions like the prefrontal cortex is important - TBIs, ASD can cause difficulties with sarcasm

attendance slides

bigfoot

man arrested in Yellowknife for kicking bison while drunk

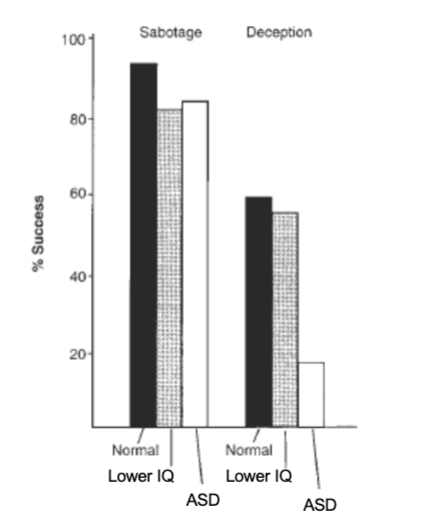

STUDY: Is Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) also associated with altered mentalizing system function? (Sodian & Frith, 1992)

three groups of children: (1) have an IQ in normal range, (2) an IQ below normal range, (3) individuals with a ASD diagnosis

1 or 2 boxes and 2 puppet characters: one that eats a smartie every time he finds one in the box and one that puts another smartie into the box every time he comes up to the box

sabotage task - child asked if they want to lock the box or keep the box unlocked when either the nice puppet or the mean puppet comes up to it (DOESN’T REQUIRE MENTALIZING)

deceptive task - no padlock, but the child can just tell the puppet whether or not the box is locked (REQUIRES MENTALIZING)

RESULTS: Is Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) also associated with altered mentalizing system function? (Sodian & Frith, 1992)

children with ASD performed the worst in the deception condition by a significant amount

children with ASD performed slightly better than low IQ children in the sabotage condition

All groups performed worse in the deception condition

DISCUSSION: Is Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) also associated with altered mentalizing system function? (Sodian & Frith, 1992)

ASD children have difficulty with inferring false beliefs and manipulating other’s beliefs

Have difficulty lying

ASD children are able to normally help the cooperator when there was a physical means to do so (a lock) - suggests a specific deficit in representation of mental states as beliefs, not in social interactive skills

How do individuals with ASD pass “false belief” tasks despite being “mind blind”? (Senju et al., 2009)

those with ASD don’t spontaneously mentalize like neurotypical individuals - they reason about false beliefs instead (using System 2 thinking)

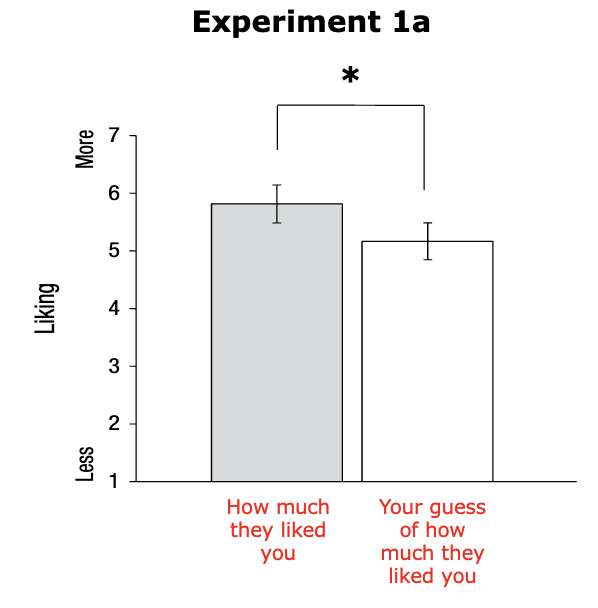

the liking gap (Boothby et al., 2018)

people underestimate how much other people like them and enjoy their company

BACKGROUND: the liking gap in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

it is difficult for us to know what our conversation partners are thinking about because people do not typically reveal their true feelings, people are reluctant to reveal their true feelings out of fear for social rejection, fail to notice people showing interest in us because conversations are cognitively demanding

we are biased by our own internal monologue, which is usually negative

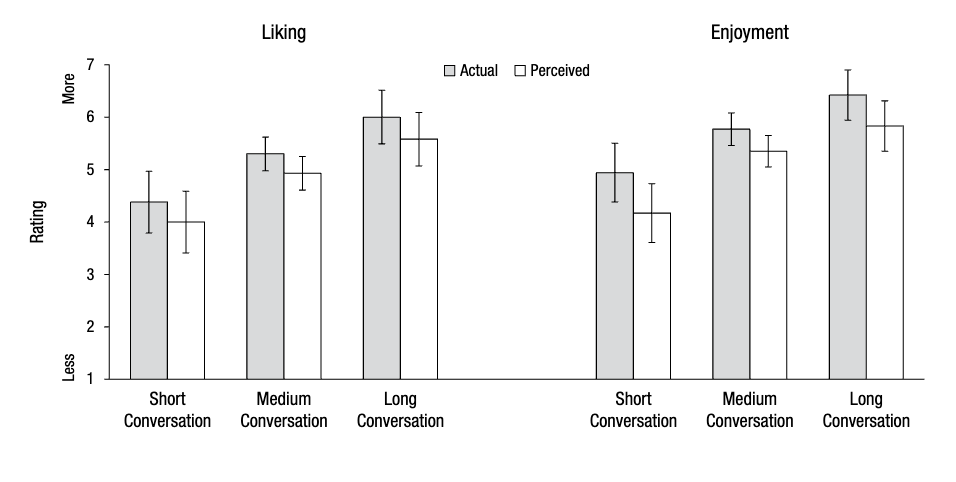

STUDIES: the liking gap in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

1a: ps had a conversation with each other, then rated how much they liked one another and how much they thought the other person liked them (is there a liking gap?)

1b: a third party watches a video of a conversation and rated how much they thought the people liked each other (no-signal vs. neglected-signal)

2: ps reported their thoughts they had about their conversation partner and the thoughts they thought their partner had about them (why the liking gap exists - negativity bias?)

3: ps had conversations with their partners for as long as they wanted, also rated how much they and the other person enjoyed the conversation

4: ps were observed at conversation workshops and rated how interesting they thought their conversation partner was and how interesting they thought their partner thought they were (do liking gaps exist in the real world)

5: college roommates continuously asked during the year how much they liked their roommates and how much they thought their roommates liked them (do liking gaps persist over time)

no-signal account in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

people not being able to tell how much their conversation partner likes them because they are not signalling that they like them

neglected-signal account in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

people not being able to tell how much their conversation partner likes them because they are not noticing or using the signals from them

overly focused on the contents of our own thoughts, which are critical and distract us from perceiving our conversation partners

STUDY 1a: the liking gap in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

found that people rated how much they thought their partner liked lower than how much they actually did

do we not want to reveal our true feelings to be polite?

are we scared to express interest because of social rejection?

are we too focused on what we should say because of the cognitive demands of conversation?

STUDY 1b: the liking gap in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

is it the no-signal or the neglected-signal account?

third-party ratings matched the actual liking ratings - neglected-signal account

STUDY 2: the liking gap in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

we think more negatively about ourselves during conversations than we do about our partner

difference in negativity and our negativity bias explains the liking gap

STUDY 3: the liking gap in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

no matter the length of the conversation, ps continuously underestimate how much their conversation partners actually like them and how much they enjoyed the conversation (short, medium, and long) - liking gap persists

ps ratings of their partner go up as conversations get longer, but the liking gap still persists

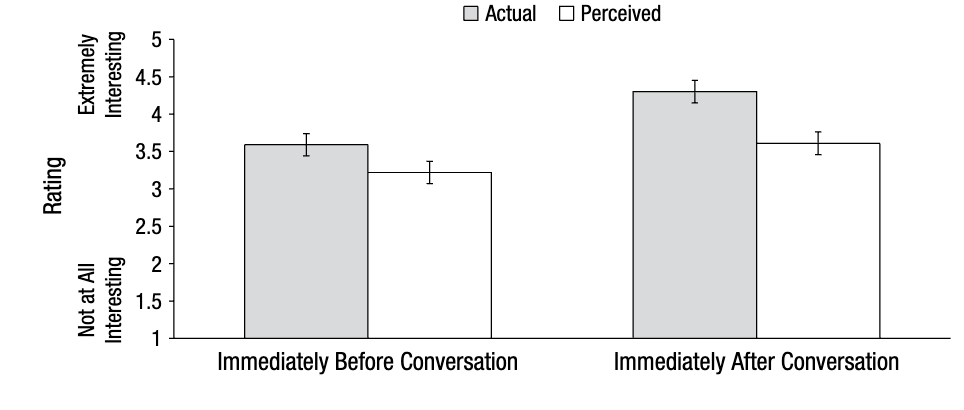

STUDY 4: the liking gap in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

the liking gap is present before and after having a real world conversation - the liking gap gets bigger after a conversation

STUDY 5: the liking gap in conversations (Boothby et al., 2018)

liking gap persists over 4/5 periods in a year - not present at the last time point

liking gap may disappear as roommates formed and developed a relationship and feel comfortable with each other

why are we so self-negative?

it aids self-improvement

we set higher standards for self vs. others

we overestimate how much we display our awkwardness

BACKGROUND: Do we also underestimate how much our conversation partners think about us after a conversation? (Cooney, Boothby & Lee, 2021)

thought gap: underestimate how much people think about us - biased to our own thoughts which are more available to us (availability heuristic)

do not have access to real-time feedback anymore

content and frequency of partner’s thoughts

self-perception of one’s own traits can allow interpretation of what others might be thinking

STUDIES: Do we also underestimate how much our conversation partners think about us after a conversation? (Cooney, Boothby & Lee, 2021)

ps have a 45 min in-lab conversation with a stranger → 2 hrs later they are sent a survey to complete that asks how much their partner was on their mind after they talked and how much they thought they were on their partner’s mind - if the thought gap exists

ps recall an argument and then reflect on their thoughts and the argument partner’s thoughts - increasing the availability of partner's thoughts to decrease the thought-gap (study 5 in paper)

to measure if rumination resulted in bigger thought gaps, ps thought about an argument they had and they completed a survey about rumination thought style (study 7 in paper)

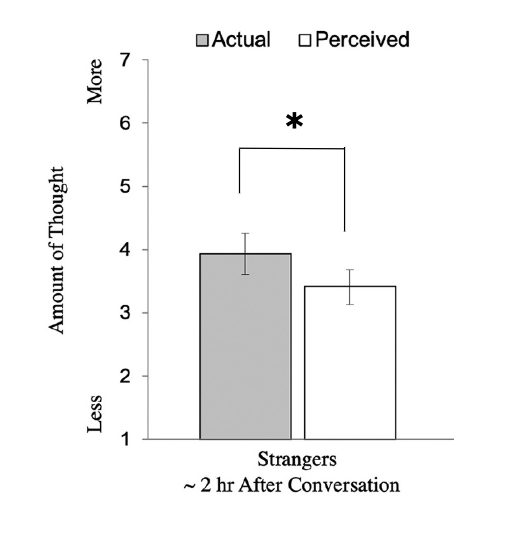

STUDY 1: Do we also underestimate how much our conversation partners think about us after a conversation? (Cooney, Boothby & Lee, 2021)

people underestimate how much others actually think of them after a conversation

why does this thought gap exist?

we have an asymmetric availability of our own thoughts compared to others’ - we have privilege to our own minds

STUDY 2: Does the availability of others’ thoughts affect our thought gap? (Cooney, Boothby & Lee, 2021)

the thought gap significantly decreases when asked to consider counterpart’s thoughts

actual thought gap remains the same when both prompted and unprompted

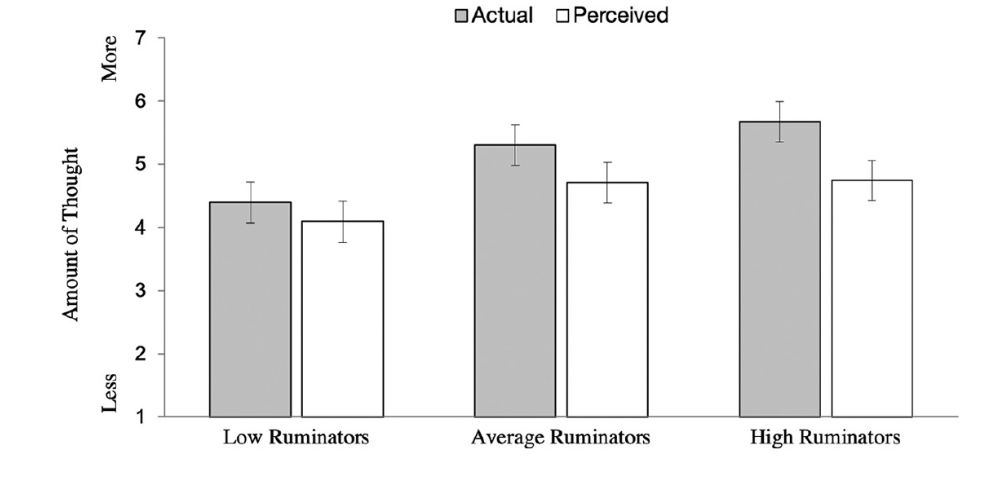

STUDY 3: Do rumination tendencies increase the thought gap? (Cooney, Boothby & Lee, 2021)

rumination tendencies do increase the thought gap - it gets bigger as rumination increases

the amount of actual and perceived thought in general increases as rumination increases

main concepts

emotion recognition

social mimicry

mentalizing

thought gap

liking gap

psychological distance

shared experiences

social power

what is psychological distance?

it can be

temporal: distance measured in time

spatial: distance measured in physical space

social: distance measured in interpersonal distanc

construal level theory explaining psychological distance

the psychological distance we perceive to an object, person, or event biases how we think about that object, person, or event

when distant, an issue is abstract (don’t conceptualize any potential conflicts or responsibilities) - desirability over feasibility

when close, an issue is concrete (suddenly have a bunch of things to do, so the fun event doesn’t sound fun anymore) - feasibility over desirability

STUDY: can language abstract and psychological distance manipulate how we feel about a destination? (Wang & Lehto, 2020)

ps were told to imagine taking a vacation trip - shown an ad for a travel destination then asked about their attitude towards the ad and the travel destination

experiment 1: temporal distance manipulated - near (travelling to a place tomorrow) or far (travelling to a place a year from now), language of the travel ad either concrete (talks about things to do) or abstract (talks about the place’s traits)

2×2 design

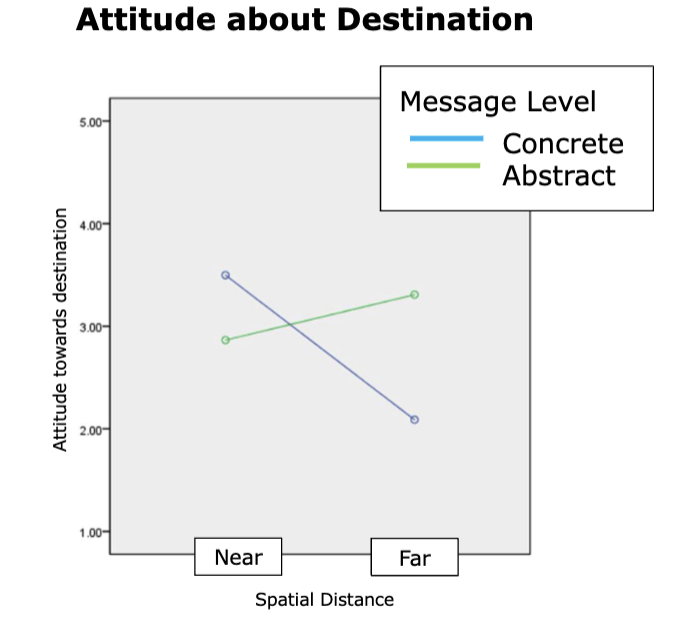

experiment 2: spatial distance manipulated - location is close (drive 2 hours) or far (fly for 12 hours), language of ad either concrete or abstract

2×2 design

STUDY 1: can language abstraction and temporal psychological distance affect how we feel about a destination? (Wang & Lehto, 2020)

people’s attitudes are better about near trips when language is concrete

people’s attitudes are better about far trips when language is abstract

STUDY 2: can language abstraction and spatial psychological distance affect how we feel about a destination? (Wang & Lehto, 2020)

people’s attitudes are better about close destinations when language is concrete

people’s attitudes are better about far destinations when language is abstract

abstract language is associated with more positive attitudes about near destinations that it was with near trips

BACKGROUND: Can the ideas of construal-level theory help explain how gift-giving impacts our sense of psychological distance? (Rim et al., 2019)

gifts can be grouped as desirable (quality, high-construal) or feasible (practical, low-construal)

increasing psychological distance from something can lead people to construe it more in terms of its central and defining features and less in terms of features considered more peripheral - things are more likely to be rated for their desirability

when receiving a feasible gift, the recipient may feel that the giver focused on their needs/low-level aspects, so they feel closer to them

STUDIES: Can the ideas of construal-level theory help explain how gift-giving impacts our sense of psychological distance? (Rim et al., 2019)

1a: ps given 2 gifts from 2 different people - a practical, but unaesthetic pen (feasible/concrete) and a fancy, but heavy pen (desirable/abstract) - then rated which gift-giver was more similar to them

1b: ps given 2 gift cards from 2 different people - for an ordinary Italian restaurant 5 minutes away (feasible/concrete) and a upscale Italian restaurant 1 hour away (desirable/abstract) - then rated which gift-giver they felt similar/closer to

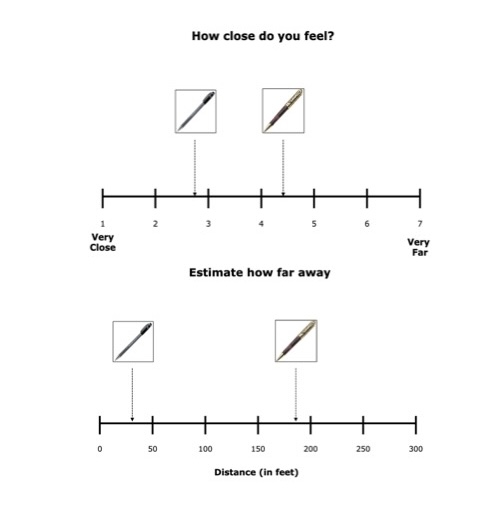

2: pairs of people split up and taken to opposite ends of a university store - each person was told their partner chose a pen to give them as a gift - after seeing the pen, they rated how close they felt to their partner and how physically far away they thought they were

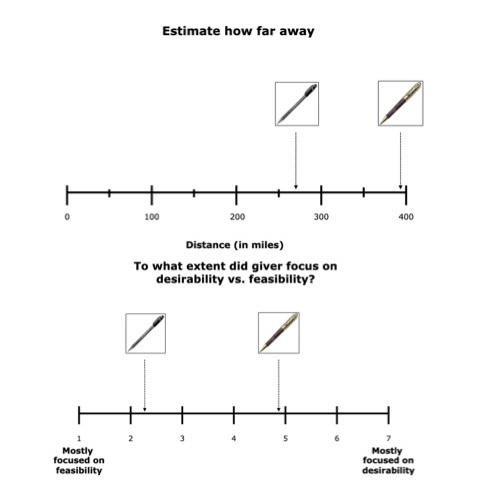

3: ps imagined receiving a pen as a gift and then estimated how physically far away the gift giver was from them and the extent they focused on feasibility vs. desirability in selecting a gift

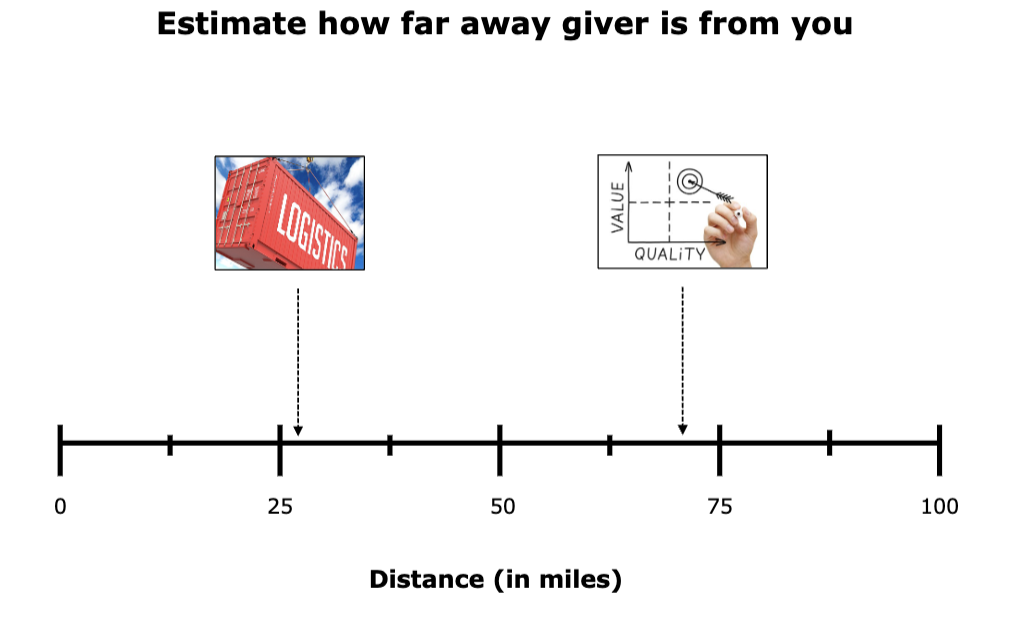

5: ps imagined receiving the same gift card and were told the gift-giver either focused on the logistics of using the gift (low-level) or the value/quality of the gift (high-level) - ps then estimated how physically far the giver was from them

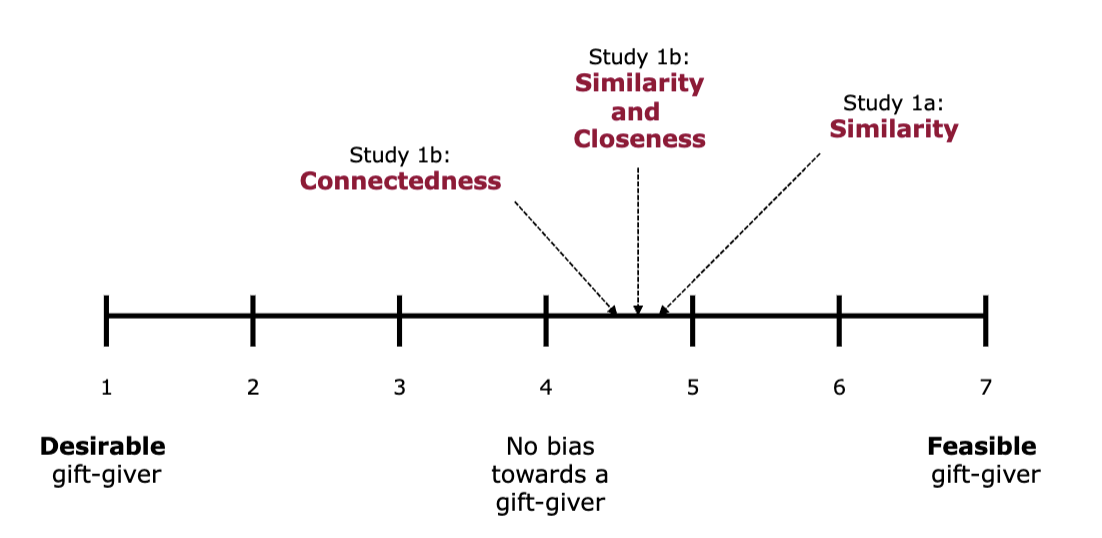

STUDY 1: Does construal-level theory explain how gift-giving impacts our sense of social distance? (Rim et al., 2019)

1a: participants felt more connected and similar to the feasible gift-givers - less social distance with feasible gifts

1b: participants also felt more similar and close to the feasible gift-givers - less social distance with feasible gifts

STUDY 2: Does construal-level theory explain how gift-giving impacts our sense of spatial distance? (Rim et al., 2019)

ps felt closer to their partners when they received the practical/feasible pen from them

ps felt physically nearer to their partner when they received the feasible pen from them

STUDY 3: Does construal-level theory explain how gift-giving impacts the sense of spatial distance within in the gift-giver instead of the receiver? (Rim et al., 2019)

ps imagining receiving a practical pen perceived the gift-giver as significantly closer and more focused on feasibility

ps imagining receiving a aesthetic pen perceived the gift-giver as farther and more focused on desirability

STUDY 5: Could the findings from Study 3 of be explained by how much the participants liked the gifts, what they perceived the costs of the gifts to be, and what their pen preferences were? (Rim et al., 2019)

ps felt closer to the person that gave them the gift that was chosen for ease/feasibility then the gift that was chosen for value/quality

even when ps knew the intentions behind the gift, they rated the feasible one higher

does sharing an experience with someone else amplify it? (Boothby et al., 2014)

ps tasted/rated chocolate while confederate does the same OR while confederate does something else

found that shared experiences amplified the liking and perceived flavour-fulness of the chocolate

does sharing an experience that is “bad” with someone else still amplify it? (Boothby, 2014)

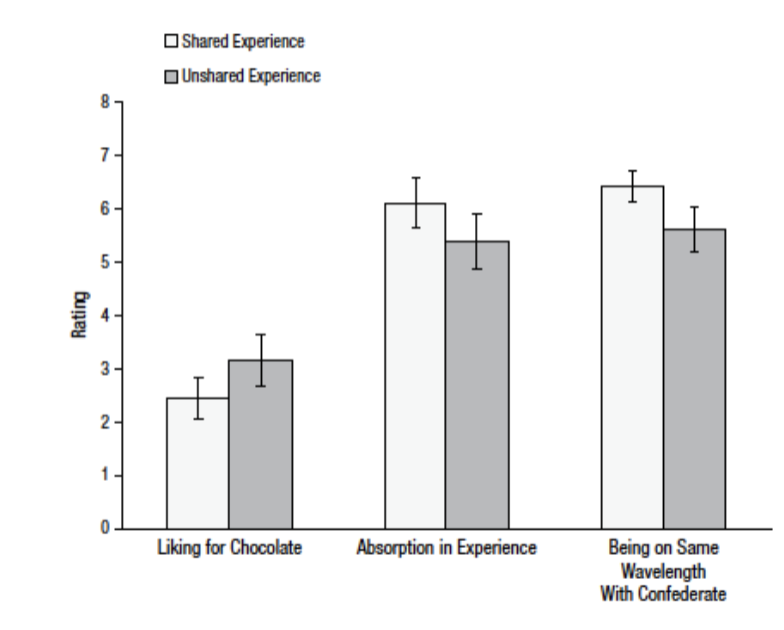

ps tried bad chocolate while a confederate did the same OR while a confederate did something else - ps also rated how absorbed they were in the experience and how much they were on the same wavelength as their partner

done to support the explanation of shared experiences being amplified when compared to unshared experiences over shared experiences just being more enjoyable in general

supplementary questions asked because people’ attention is naturally drawn to the focus of other person’s attention, so people may feel more absorbed in the stimuli when experience is shared and sharing of an experience might lead to more mentalizing, which can increase impact of shared experience

if people thought more about partner’s thoughts/feelings during shared experience

ps liked the chocolate less when the experience was shared, but they also rated their absorption in the experience and similarity to their partner higher

STUDY 1: does sharing some identity features with others result in a greater sense of social identification? (Shteynberg & Galinsky, 2011)

ps chose an avatar for an online interaction with two other people that either matched or didn’t match the avatars of the others, then they rated how social they felt during the interaction

Ps in the similar-others condition felt more social

avatars can be supplemented to manipulate social groups

STUDY 2: does sharing of promotion goals with similar others lead to increased promotion behaviour? (Shteynberg & Galinsky, 2011)

ps reviewed a set of 9 nonsense words and then identified the nonsense words they just saw vs. new ones on a list

between-subjects - social group (similar or different others) and sharing of task goal (yes or no) was manipulated

similar ps sharing a task goal made the least amount of errors - indicates that effect was specific to adoption of a promotion goal rather than just general performance improvement

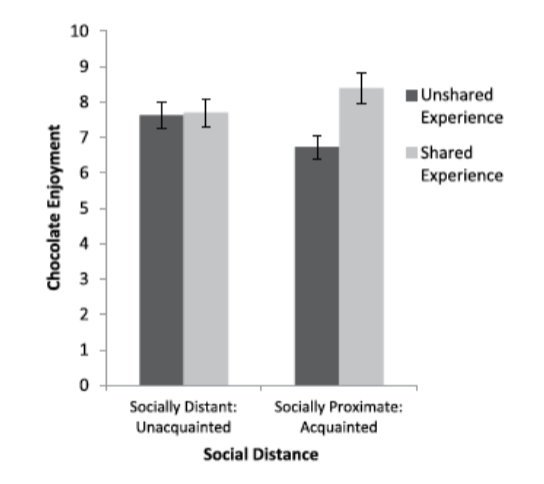

does psychological distance moderate the amplification of shared experience? (Boothby et al., 2016)

ps tasted chocolate while confederate did the same and then tasted chocolate while confederated didn’t do the same → they either were put in a social proximate condition (got acquainted with the confederate before shared tasting) or a socially distant condition (didn’t get acquainted)

people enjoyed the chocolate the most when they had a shared experience while acquainted

BACKGROUND: Are we more willing to cooperate with others if we share a negative vs. positive experience with them? (Qi et al., 2022)

previous research supports positive experiences strengthening cooperation, but an increasing number of studies show negative experiences can too (promote interpersonal relationships - empathy, trust, social bonding)

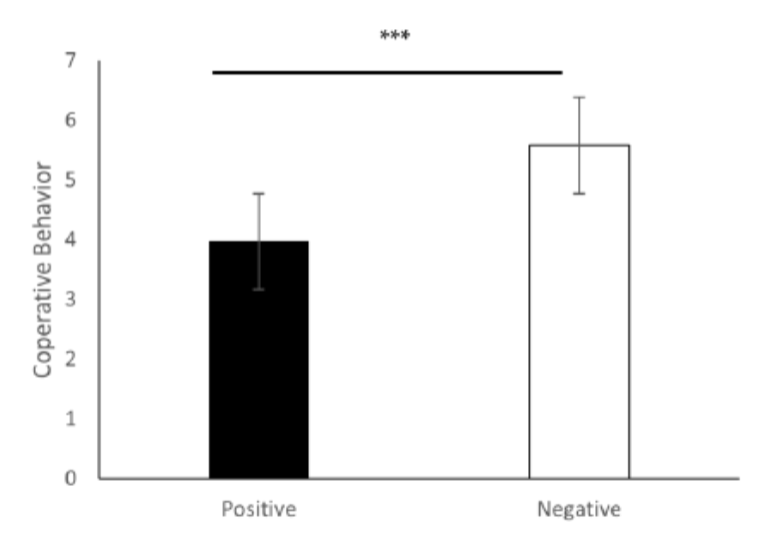

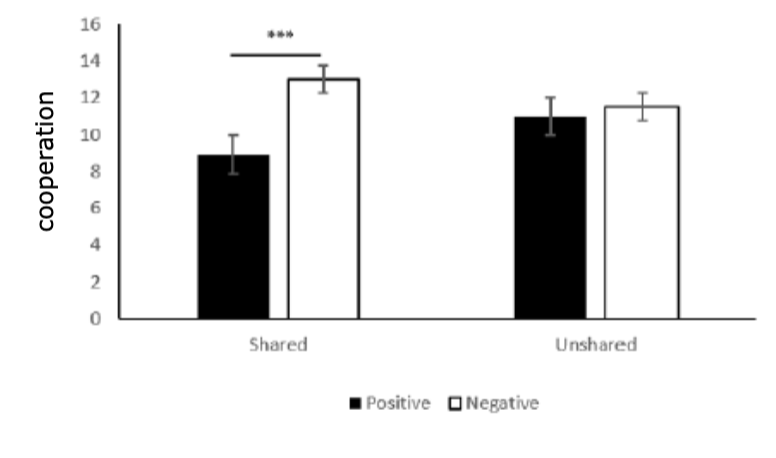

STUDIES: Are we more willing to cooperate with others if we share a negative vs. positive experience with them? (Qi et al., 2022)

1: ps in groups of three or 4 were either given rock candy to taste (shared positive experience) or chilli peppers to share (shared negative experience) → then they played a cooperation game

2: same as experiment one, sharing is now manipulated - partners are tasting the same thing as you (shared) or something different than you (unshared)

STUDY 1: Are we more willing to cooperate with others if we share a negative vs. positive experience with them? (Qi et al., 2022)

ps were more likely to display cooperative behaviour if they had a negative shared experience together

STUDY 1: Are we more willing to cooperate with others if we share a negative vs. positive experience with them where we all experience the same thing? (Qi et al., 2022)

ps cooperated the most when all ps shared experiencing a negative thing with each other

how does peter from office space change after being hypnotized to be less of a push-over?

before

spends more time trying to avoid his boss

doesn’t say anything when his boss asks him to work on the weekend

low power

after

doesn’t care about what his boss tells him to do

honest about how boring his job is and how little he works

his self-imposed high power leads to him getting a promotion

the more power we gain, the less we mentalize about other people

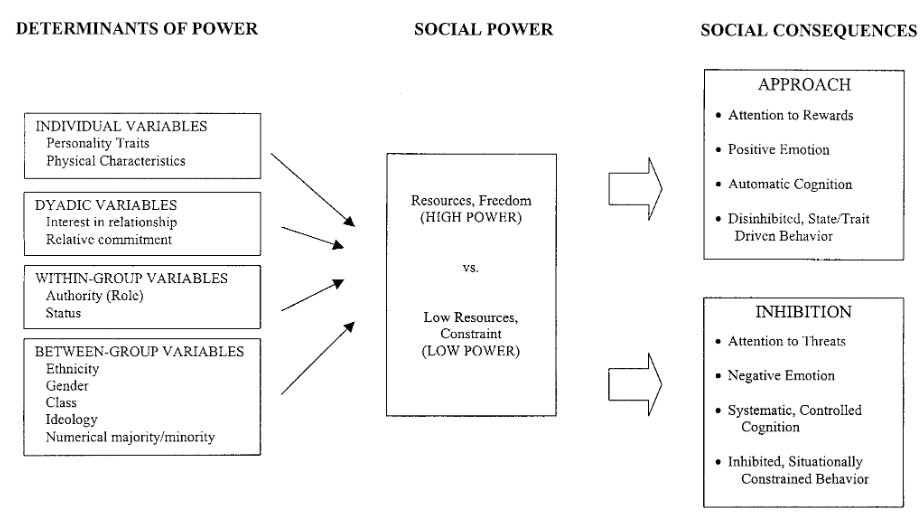

a cognitive model of social power (Keltner, 2003)

Determinants of power

individual: personality, physical (attractiveness)

dyadic: interest in relationship (networking), commitment

within-group: authority, status

between-group: ethnicity, gender, class, ideology, minority groups

Leads to high power (resources and freedom) or low power (low resources and constraint)

High power = approach social effects: attention to rewards, positive emotion, automatic cognition, disinhibited, state driven behaviour (system 1 thinking)

Low power = inhibition social effects: attentions to threats, negative emotion, systematic/controlled cognition, inhibited socially constrained behaviour (system 2 thinking)

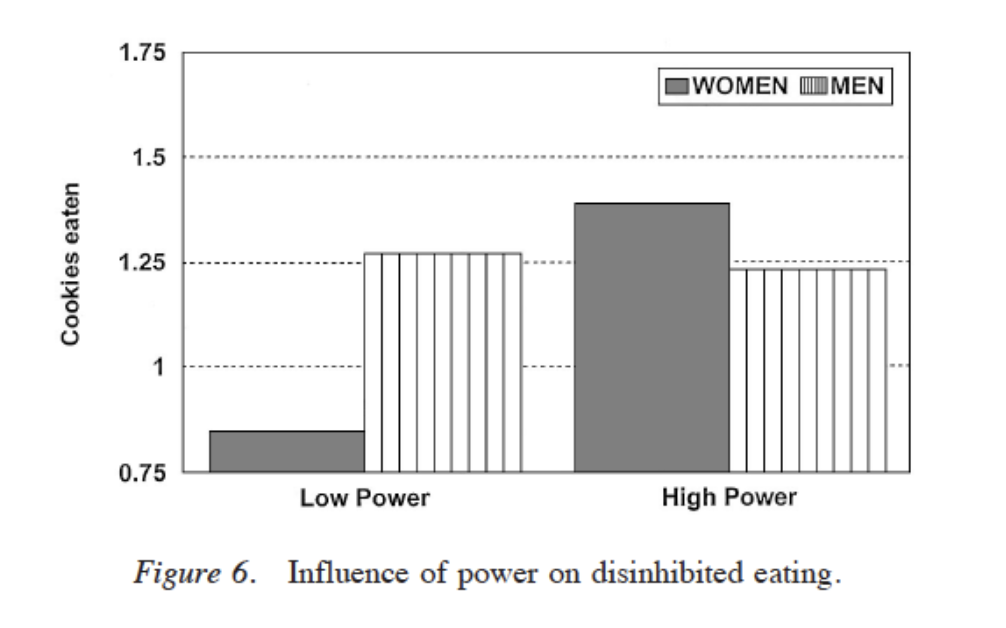

Does social power actually lead to disinhibited behaviour? (Keltner, 2003)

3 same-sex ps work on a project together with one person designated as the leader - a plate of 5 cookies left on the table (only 2 people can have a second one - does power influence who eats the cookies?)

found that high-power individuals were more likely to a second cooker

men were not affected by the power manipulation - ate almost the same amount of cookies in low and high power conditions

only for women

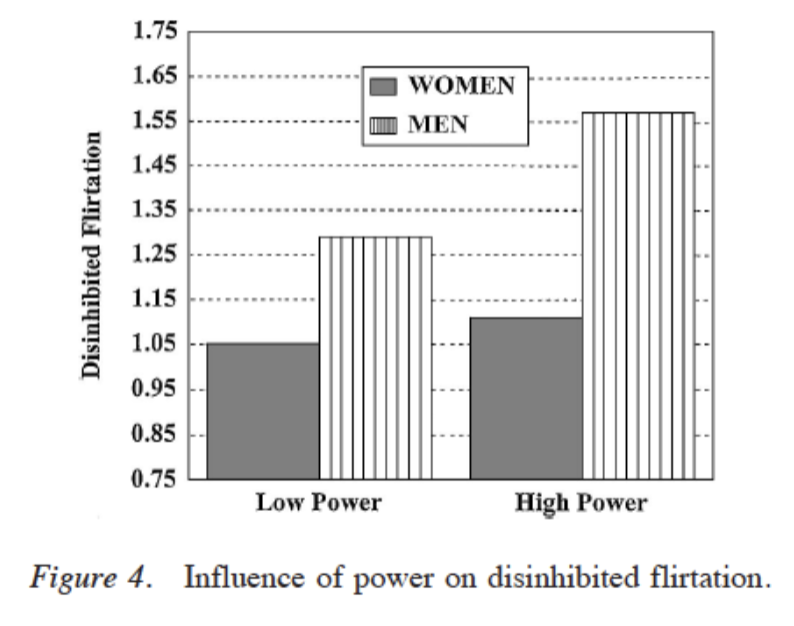

Does social power specifically lead to an increase in flirtatious behaviour? (Keltner, 2003)

ps interact with member of opposite sex under equal power conditions OR when one is designated as responsible for giving out extra credit points

men flirted more than women in both low and high power conditions - flirting significantly increased for men in high power condition

flirting by women only increased slightly in high power condition

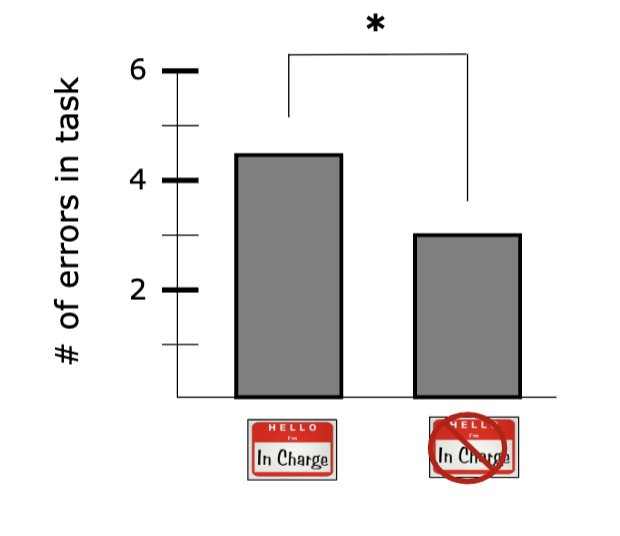

Does social power impact social cognition, or our capacity to think about others? (Galinsky, 2006)

ps were told to write about a time when they were in charge of someone (primed for high power) or about a time when someone else was in charge of them (primed for low power) → ps then did an emotion recognition task

found that ps primed for high power made more errors in emotion recognition

Does social power cause people to take more of a self-oriented perspective on things? (Galinsky, 2006)

ps were told to write about a time when they were in charge of someone (primed for high power) or about a time when someone else was in charge of them (primed for low power) - ps were then told to draw an E on their forehead (self-oriented E = backwards to everyone else, other-oriented = backward)

found that ps primed for high power were more likely to write a self-oriented E

does social power influence perception of one’s humour? (Stillman, 2007)

ps watch a video with some funny jokes and some unfunny jokes - power status at imagined job was manipulated

either you are the boss, watching your subordinate joke (high power), you are the subordinate watching your boss (low power), or you’re a coworker watching a co-coworker (equal power)

found that the humour response to funny and unfunny jokes from high power people was the lowest

social bonding hypothesis

social bonding hypothesis

low power makes people more incline to laugh because it serves to strengthen social bonds and elicit liking in other individuals, which increases chances of gaining social support

Rudolph: the other reindeers were just young trainees and didn’t a lot of power, so when they laughed at Rudolph, it strengthened the group bonds around making fun of Rudolph