Applied neuropsychology

1/40

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

41 Terms

What is neuropsychology?

the study of the brain and how chan goes it can affect emotions behaviours and cognition.

supporting people with a neurobiological diagnosis or symptoms to manage and adjust to changes relating these difficulties.

providing support and guidance to family and close others.

working with those who supports with individual who is experiencing these changes (emotionally and sometimes practically too).

Who do neuropsychologists work with?

people with an acquired brain injury

trauma

stroke

tumour and post-surgical injury.

people with a degenerative neurological condition

dementia

neurodegenerative

people with a functional neurological disorder

the families “careers”, and organisation supporting the person with a neurological condition or symptoms.

how does neurological conditions related to distress?

Wide-range of neurological conditions, but sime shared or common difficulties

severity can vary widly, from a “prolonged disorders of consciousness” to a return to previous work and activities with lottle or no visible ongoing function or psychological change.

What can distress result from?

Biological or physical changes

social changes

psychological changes

What does the literature say about neurological conditions and distress?

Psychological and behavioural difficulties are common following an acquired brain injury, remaning prevalent at least a decrease later (Thomsen ,1984)

frequent difficulties include:

self-isolation

emotional lability

apathy

“aggressive” behaviour

reduced social awareness

reduced empathy

suicide attempts and self-harming behaviour

“rule-breaking”

some of these are commonest when there are communication difficulties.

Even more complex when cognitve symptoms interact with/cause these.

additional stressors where there are aspects of heritability, family conflict and care responsibilities and intergenerational trauma.

What are possible biological changes?

physical changes in the brain-damage to the emotion centres (limbic system, amygdala)

hormone imbalances- damage to the hypothalamus and pituitary gland

pain- sensory disruption or physical changes in mobility

changes to awareness- seizures

reduced energy and/or increased fatigue or sleepiness

What are possible social changes?

losing or changing roles and responsibilities (work, family roles)

financial implications

lessened ability to understand and cope with social interactions- can make a person want to avoid others

others might not understand how it feels their reaction makes things feel more difficult.

What are the possible psychological changes?

shock: potential sudden change in self-identified, expectations, personal narrative

frustration, angry, and denial: feeling of injustice, “i dont deserve this”< “this cant be happening to me”

low mood (depression, hopelessness): realising loss, changes in abilities, lifestyle, roles, and relationships, self-image, hope, and plans for the future.

anxiety: noticing changes in thinking skills personality, how others are reacting to us.

low motivation: “theres no point”, “nothing i can do will change anything”

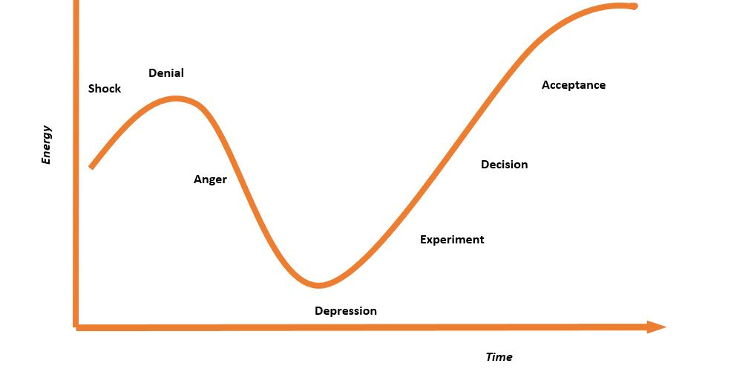

What are the five stages of grief? change curve

written for people at the end of their life- may find yourself on different stages day to day.

hope for people to be more on the right side of this graph.

reaching a stage to live well with whats happening

prehaps adjustment rather than acceptence

What is the change curve with people with multiple sclerosis?

Want to see the five stages of grief ehrn someone is diagnised with Multiple sclerosis

First 6 months: high anxiety, decreasing towards the end of the first year

From the end of the first year, depressive symptoms began to increase, peaking at the 20th month.

sign that anxiety is common early and low mood later on- the researchers sya this fits the 5 stages but research emphasises other things- no trajectory- small sample size.

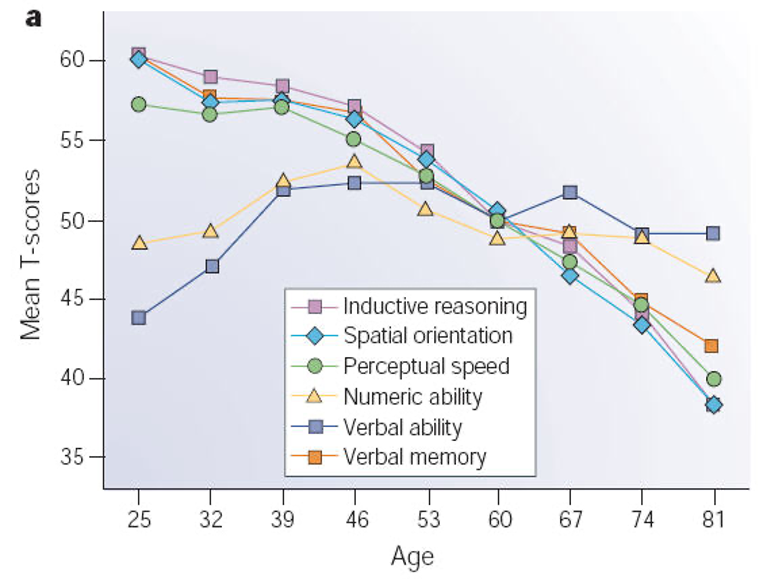

What is “typical” aging?

older adults experience increasing cognitive deterioration after age 50.

with 12.3 million people in the uK aged 65+ rising to 25% by 2050 these changes in cognition affect wellbeing, work and dauly living fir a huge population

settle ageing study showing global decline and limited expectation

What ageing is noticed first?

Memory:

- Worsened ability to memories and retrieve information, including remembering information about people, appointment, and daily tasks like taking regular medication.

Attention:

- Difficulty concentrating on important information, filtering out distractions, and multitasking- all of which can affect daily tasks and work performance.

Speed of processing:

- Becoming slower o understand information, complete tasks, or participants in conversations. This can affect safety, work, and self-image

Executive function:

- Struggling with complex cognitive abilities such as problem solving, planning, and responding flexibility to changing situations. These changes can cause widespread difficulties with home management, relationship, and working life.

What is shame and stigma in cognitive ageing?

people with visible physical signs of ageing and illness experience distress linked to felt shame and perceived stigma.

so having cognitive difficulties evidence to others may cause similar problems

participants in informal participants engagment groups report embarrassment at symptoms like forgetfulness, or noticing that other treat them as less capable

this consonant with findings that people with dementia

experience shame

avoid potentially embarrassing situations

view themselves negatively

lose faith in their abilities due to their cognitive symptoms

these worries may parallel those experessed by people with dementia:

Who also often express concern about stigma from others

24% fear stigma

40% feel excluded from society

Mental health symptom prevalence in older adults reaches an estimated 32-37%

Current approaches to older adult mental wellbeing are inadequate, and new models are urgently required

Research currently under way in this department to explore these issues further

why can “typical” ageing can be distressing too?

As a clinical psychologist in neuropsychological settings, you often meet people who are worried about their cognition

All of them will benefit from feeling validated and respected, with their worries taken seriously – just because someone doesn’t have a “diagnosable” issue, doesn’t make the rest of their concerns go away

This can also mean challenging our own expectations and biases about ageing

What is functional neurological issues/

people experience physical difficulties, weakness, paralysis, tremors or spasms in your muscles

experience numbness, tingling or pain

seizures, black out or faint

critically people often get diagnosis when other options have been exhausted, and there is often no obvious physical causes

this can have huge impacts on self-image and relationships with helthcare processionals.

Possible contributing factors of functional neurological diaorders?

Previous experience of trauma

Emotion regulation difficulties

Expression of psychological distress as physical symptoms

Low mood or anxiety

Stressful life events

Experiencing epilepsy or having a family member with epilepsy.

What does FND mean from the clients perspective?

- You have frightening symptoms which indicate a serious neurological problem, but no one can tell you why

- You’re given a diagnosis, often after years of being sent from service to service with no progress, and eventually sent to see a psychologist

- By this point, people are often worrying it’s “all in their head” (and some have even been told exactly that)

- Therapy is often about building an understanding of the role of stressors, low mood, anxiety and systemic difficulties in wellbeing, and when they may contribute to “functional” difficulties

What is stigma around people with FND?

Stigma around people with functional neurological difficulties can affect diagnosis, treatment, and research

Symptoms can be misunderstood, invalidated, or dismissed

Surveys document frustration experienced by providers and distressing healthcare interactions experienced by people with these difficulties

MacDuffie et al. (2020) identified the need to investigate further:

The prevalence and context of FND stigma

Its impact on people with functional neurological difficulties and healthcare providers

Developing ways to reduce stigma among healthcare professionals and wider society

What is Huntington’s disease?

rare, life-limiting neurological disease: about 10 in 100000 people.

cause by a CAG expansion on the HTT gene

Dominant gene: inherited from an affected parent

mutant huntingin cauases symptoms

What are symptoms and difficulties that come with HD- onset?

Motor symptoms:

Start around 30-50 years old

Include “chorea”, “rigidity,” “bradykinesia” which are used diagnostically

Effects on independence, for the affected person and those around them

BUT

Cognitive, behavioral and emotional changes predate physical changes by at least 15 years

What are the cognitive changes in HD?

Memory

orientation

speed of processing

executive function

inhibition: putting the brakes on

cognitive flexibility: switching tack

working memory and loss of multitasking

anosognosia: loss of insight (Implication for safety and healthcare.

What are other insights into HD?

People with HD may have a wide range of mental health difficulties

Communication can get in the way (physical, cognitive issues, personality!)

People with HD report fewer symptoms than their carers do about them, and overestimate their abilities (Simpson et al., 2016)

Only reports from an “informant” (someone close to the person with HD) have been shown to have predictive validity about abilities years into the future (Duff et al., 2010)

A study who invetsiated insight in HD…

Key question: Does it make mental wellbeing assessments more accurate, if you have an “informant” (close other) come to appointments with a person with HD?

Evaluated differences in psychological symptom reporting with and without an informant present

Four groups (n = 7914):

• “Manifest” HD – after onset of motor symptoms

• ”Premanifest” HD – before onset of motor symptoms

• “Genotype negative” people – once at risk, but have tested negative

• “Family controls” – from HD-affected families, but have never been at genetic risk

What was found?

For assessments of apathy, having a close-other present to provide extra information DID push scores up compared to self-rated scores by a person with HD alone

- So people with HD may underestimate their apathy levels, but someone who knows them well can adjust that score up

- They can (we theorised) do this because apathy is visible. A person becomes less responsive, less active, and an observer can see this, especially one who knows them well

– For affect (anxiety, low mood, suicidal thoughts) it made no difference if the person with HD came alone, or with an informant

– Two possible reasons:

– Differences in insight between domains?

– Affect is less observable than apathy?

– Scores were higher not just for manifest HD group, but also for premanifest and genotype negative groups when an informant was present – scores adjusted up by the close other in all cases

– Fits with a relevant past finding: irritability self-ratings diverge most before cognitive changes (Chatterjee et al., 2005)

– Social undesirability of “irritability”? We just completed a study to investigate this, building on our review finding that irritability in HD is poorly understood (Simpson et al., 2019; Tindall et al., 2025)

What is family and context in HD: does it matter?

HD is entirely genetically determined. if you carry the expanded gene, you will develop HD.

but mental health symptoms, while known to be very common in HD compared to populations without a neurological diagnosis, are not linked to progression in the same way as cognitive and physical issues are.

to find out the systemic impacts of HD, we can look at HD- affected family systems (rather than individuals) and see whether everyone is experiencing poorer me tal wellbeing, or just the people carrying the HD gene expansion.

What else may be causing distress in HD?

changfes in narratives and expectations

grief and loss

worries for relatives

financial stressors

affects relavtive without HD as much as people with hD

What is the heritable component of living with HD?

children of affected parents have 50% risk of inheriting the disease themselves

predictive genetic testing is availble from 18 yeards onwards (although the vast majority dont undertake it)

multiple family members can be affected: high burden on families with intergenerational trauma, grief and loss

Think about the adjustment journey again, and how that might look with ongoing re-traumatization over time

In Maltby et al. (2021), we used factor analysis to examine what mental health difficulties looked like in those same four groups:

“Manifest” HD – after onset of motor symptoms

“Premanifest” HD – before onset of motor symptoms

“Genotype negative” people – once at risk, but have tested negative

“Family controls” – from HD-affected families, but have never been at genetic risk

What are four factors consistent across groups?

Factor 1: anxiety

- Dread

- Inability to relax

- Panic

Factor 2: depression

- Not enjoying life

- Cant find the fun any more

- Not looking forward to the future

Factor 3: outward irritability

- Loss of temper

- Slamming doors

Factor 4: self-harm

- Suicidal ideation

- Self-harming

What is severity of symptoms?

• No difference between groups for anxiety (a symptom considered characteristic of HD)

• For depression and outward irritability, the manifest group only differed from the genotype negative group consistently

• Only scattered differences from the premanifest and family controls

• The exception was self-harm, where the manifest group differed consistently from all other groups

• Overall – far less difference than expected

why does understanding severity of symptoms matter?

• Understanding mental wellbeing for people with HD helps to improve care and open up new therapy options (currently not effective enough) (Zarotti et al., 2022)

• Provides a level of confidence to mental health professionals not specialising in HD

• Highlighting psychological needs for HD-affected families can improve support.

What are neurological conditions in general?

- As psychologists in neuropsychological settings, we face a challenging situation therapeutically and personally

- Our clients may not recover; in many cases we and they know they will get worse and eventually die (HD, but many other examples)

What kind of support can be offered?

- What a neuropsychologist (or clinical psychologist in neuropsychology) does varies a lot (affected by the context and remit of the service where they find themselves):

o Providing therapeutic support to an individual around adjustment, emotional management and managing changes

o Supporting relatives or others close to the individual, emotionally and/or practically (adjustment, relationships, coping with ”symptoms”)

o Co-working with “carers” and others in the interdisciplinary team to change how they interact with a person, e.g.:

§ Supporting with “behavioural management” and changing staff attitudes to “behaviours of concern”

§ Modelling positive engagement or strategies to help the person cope differently, to reduce risk and to enhance quality of life

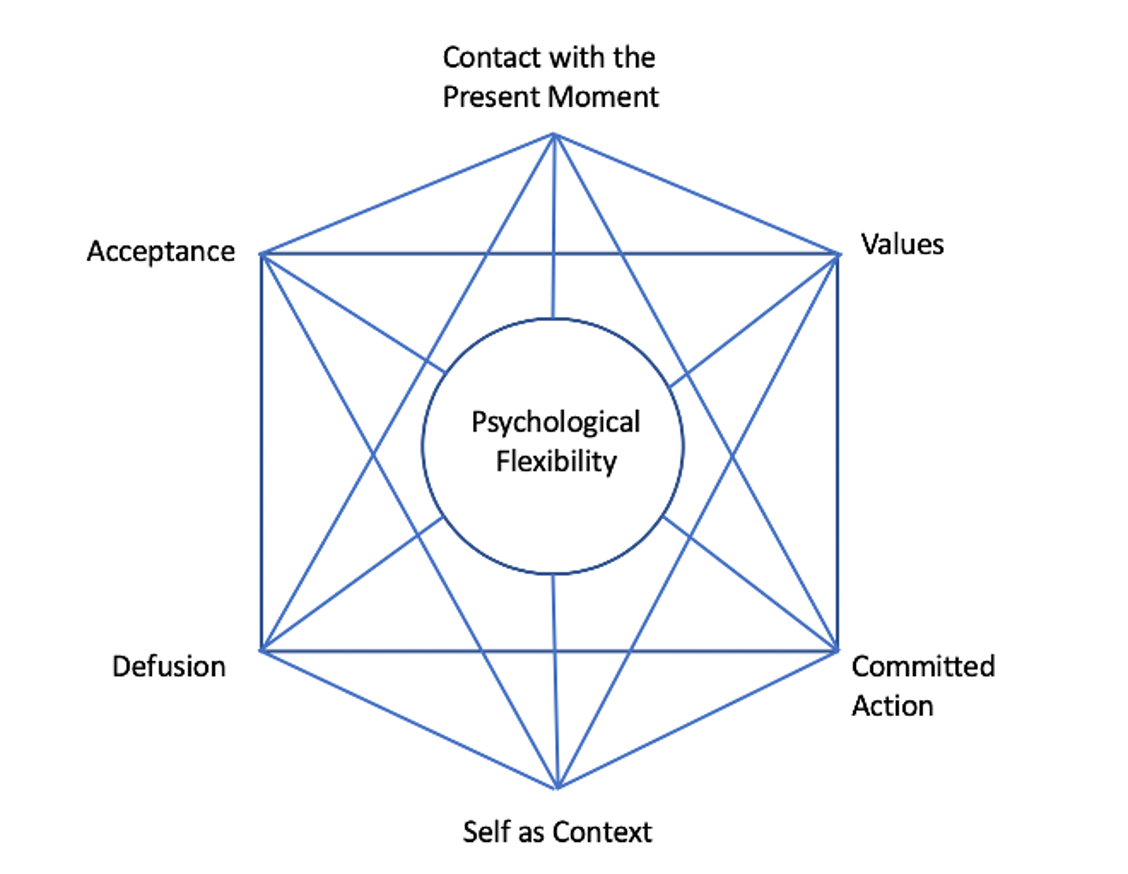

What is acceptance and commitment therapy?

- Third wave intervention, rooted in cognitive behavioural therapy

- Grows out of similar understandings about interrelations between thoughts, feelings, physical sensations, and behaviour

- But focuses less on what is “wrong” (or to be fixed) in the individual, and more on adjusting to difficult situations, promoting valued living, and enjoyment of life

- These are really important for neurological conditions where fixing isn’t possible, and acceptance of tough realities can be crucial

- Over 700 randomized controlled trials of ACT efficacy, including specific trials in neurological conditions such as acquired brain injury

- See our review paper (in refs): Buswell et al. (2025)

What is the CBT “hot cross bun”?

What is the ACT “hexaflex”

6 Core processes -

what is cognitive defusion?

o The ability to take a step back from thoughts, emotions and sensations; to see them as stories told by our minds

o These stories can be incredibly compelling

o We don’t have to accept them– sometimes they’re not helpful or accurate, but the important thing is we can choose

o ACT is full of metaphors (adapted to work with the client) – typical ones include:

Ice cream in a shop

The toxic parrot

What is acceptance?

is the ability to make space for distressing thoughts, images, emotions, sensations

Accepting that they cannot be got rid of: pain is part of life

Concept of “clean” and ”dirty” pain (or suffering)

We can learn to make space for the unavoidable difficult experiences, in order to live a “valued” life

What is ACT key points for theraputic work?

- Being in the present moment is a skill we support people to develop through mindfulness practice – focusing the attention on specific stimuli like:

o The breath

o The physical self

o An activity (can be as banal as washing up!)

o The inner experience of thoughts, sensations, emotions

- Noticing what is actually going on, rather than (as we tend to do, especially when stressed or unhappy) spending all of our time worrying about the future, or thinking about the past.

What is self context?

- Learning to see oneself as a container of experiences, not the experiences themselves

- We can witness our emotional reactions, our distress, the stories our minds tell us – but remain distinct from them

- Example of a glass of water: you are the glass, not the water (or the sky, not the clouds)

What is finding your values?

- These are your underlying guide to life, helping you to make choices that are right for you – think of them like points on a compass, showing you the way to go

- Examples might be:

- Being a hard worker

- Taking care of people we love

- Contributing or achieving in some way

- Values are not goals – goals can be completed and ticked off, values remain

- This is especially helpful for people who have experienced a major change in life (e.g., due to sickness or injury)

- Real examples:

o A person may miss climbing, but they now need a wheelchair and cannot physically do it. But what they valued was (and still is) the sense of adventure and pushing themselves

o Another person may miss running marathons, but their value was (is) tenacity and gaining money for charities

- So values can point the way to regaining pleasure and fulfilment

What is committed action?

– Once we have supported a person to identify their values, they can start finding ways to change their behaviour and explore new options (back to the adjustment journey again!)

– They can then find new ways to live in line with those values, and lead a richer, fuller, more meaningful life, despite the effects of any neurological condition or difficulties