Economics 1010 - Chapters 9 & 10

1/52

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

53 Terms

Market Structure

All features of a market that affect the behaviour and performance of firms in that market, such as the number and size of sellers, the extent of knowledge about one another's actions, the degree of freedom of entry, and the degree of product differentiation.

Market Structure — Competitive Markets

A market is said to be competitive when its firms have little or no market power.

The more market power the firms have, the less competitive is the market.

The extreme form of competitive market structure occurs when each firm has zero market power.

Lots of firms in the market, so each must accept the price set by forces of demand and supply.

Firms can sell as much as they want at the market price.

Increase in p → no sales, because so many other firms are selling at the market price that buyers take business elsewhere.

Decrease in p → profit < 0 (we will see).

Market Power

The ability of a firm to influence the price of its product.

Theory of Perfect Competition

The market structure applies directly to a number of markets and provides an important benchmark for comparison with other market structures.

Many markets are highly competitive, such as:

Agricultural products (e.g., wheat, corn, fruits).

Raw materials (e.g., gold, natural gas).Financial markets (e.g., stocks, bonds).

Online retail marketplaces.

Perfect Competition

A market structure in which all firms in an industry are price takers, and in which there is freedom of entry into and exit from the industry.

Theory of Perfect Competition — Assumptions

These assumptions imply that no single firm can influence the market price.

Each firm is a price taker: it can sell as much as it wants at the prevailing market price.

Firms adjust output to maximize profits, but the market determines the price.

Perfect competition ensures that prices reflect the efficient allocation of resources.

The theory of perfect competition relies on four assumptions about firms and industries

Firms sell an identical (homogeneous) product.

Consumers have full knowledge of product characteristics and prices.

Each firm is small relative to the industry: its minimum efficient scale is minor compared to total industry output.

Freedom of entry and exit: firms can enter or leave the industry without legal or regulatory barriers.

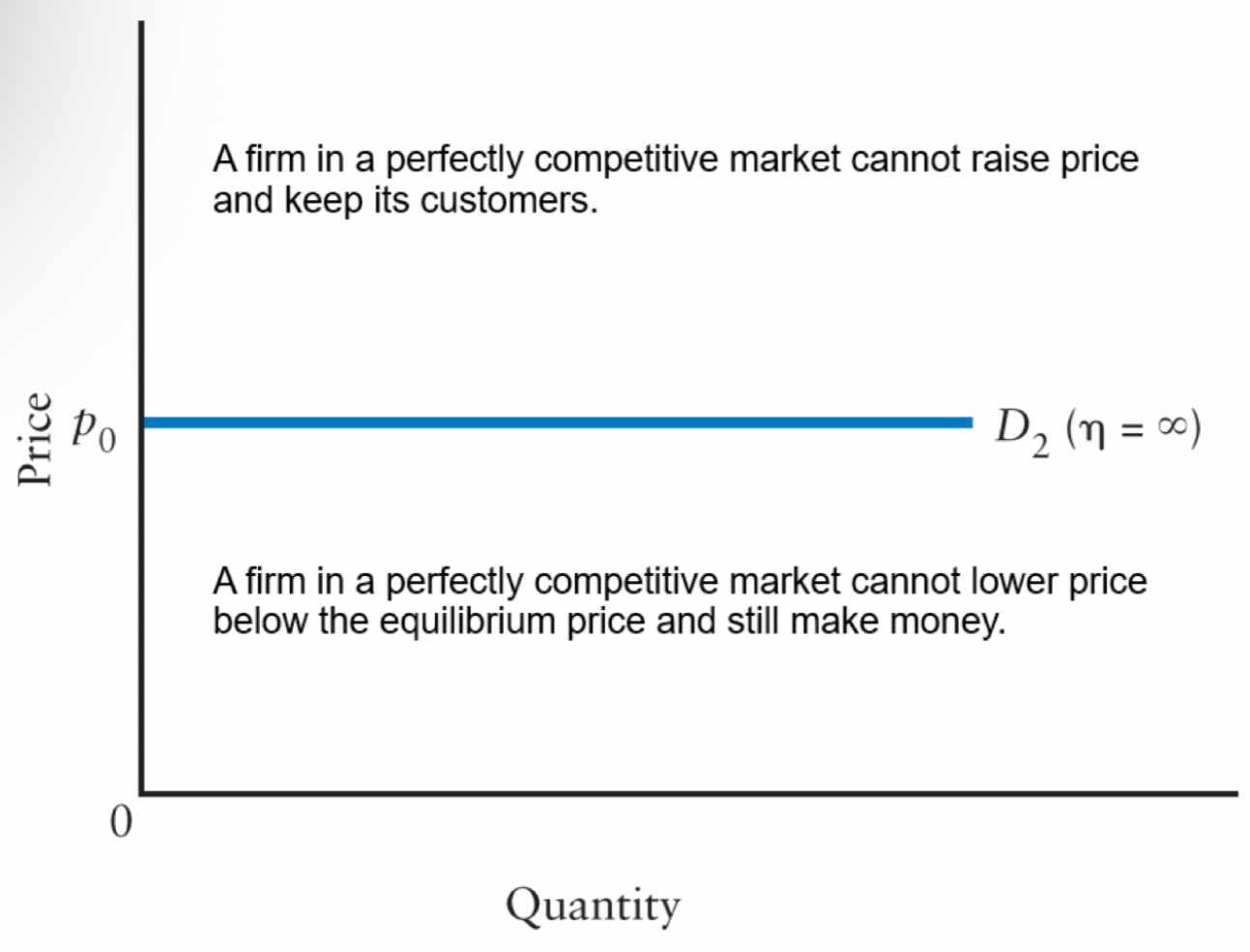

Theory of Perfect competition — Demand Curve

Compare the demand for an industry to the demand for one firm.

Industry demand curve is negatively sloped (i.e., law of demand).

Each firm is too small to produce enough to affect total industry output.

Each firm faces a horizontal demand curve, which reflects price-taking behaviour.

Theory of Perfect Competition — Revenue

To study the revenues that firms receive from the sale of their products, economists define three concepts called total, average, and marginal revenue.

Total revenue is the total amount received from sales.

Average revenue is revenue per unit sold, which equals price.

Marginal revenue is the change in total revenue from selling one more unit.

When price is fixed, it follows that p = AR = MR.

Because price does not change as a result of the firm changing its output, neither marginal revenue nor average revenue varies with output.

TR = p x Q is an upward-sloping straight line from the origin.

For a competitive price-taking firm, market price is the marginal (and average) revenue.

Short-Run Decisions

A firm's profit is the difference between total revenue and total cost

If total revenue is less than total cost, economic profit is negative and so we say the firm is making an economic loss.

To understand firm behaviour, we ask two key questions:

"Extensive margin" decision: Should the firm produce any output at all, or shut down and produce nothing?

"Intensive margin" decision: If it should produce, what level of output will maximize profit?

• We will answer these questions in turn.

Short-Run Decisions — Whether to Produce

Any firm always has the option of producing nothing.

If it chooses to produce nothing, what is its economic profits?

In the short run, fixed costs (e.g., the costs associated with plant, capital and equip-ment) are fixed and must be paid regardless of the level of output.

Put differently, fixed costs are a sunk cost in the short run.

Since it must pay its fixed costs in any event, it is worthwhile for the firm to produce if it can find some level of output for which revenue exceeds variable cost.

Sunk Cost

A cost that has already been incurred and cannot be recovered.

Shut Down Price

The price that is equal to the minimum of a firm's average variable costs. At prices below this, a profit-maximizing firm will produce no output.

Extensive Margin (Rule 1)

A firm should not produce at all if, for all levels of output, total revenue (TR) is less than total variable cost (TVC). Equivalently, the firm should not produce at all if, for all levels of output, the market price (p) is less than average variable cost (AVC).

Short-Run Decisions — How Much to Produce

If a firm decides that, according to Rule 1, production is worth undertaking, it must then decide how much to produce.

Maximize total profit by making marginal (i.e., incremental) production decisions.

If any unit of production adds more to revenue than it does to cost, producing and selling that unit will increase profits.

Formally, a unit of production raises profits if the marginal revenue from selling it exceeds the marginal cost of producing it.

A profit-maximizing firm will produce output that equates its marginal cost of production with the market price of its product, i.e., p = MC.

Intensive Margin (Rule 2)

If it is worthwhile for the firm to produce at all, the profit-maximizing firm should produce the output at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

Short-Run Decisions — Supply Curve for One Firm

Now that we know how a perfectly competitive firm determines its profit-maximizing level of output, we can derive its supply curve.

The perfectly competitive firm adjusts its level of output in response to changes in the market-determined price.

Short-Run Decisions — Supply Curve for an Industry

If this is what each producer does, it is also what all producers do taken together.

The theory of firms predicts an upward sloped market supply curve as a consequence of the increasing marginal cost for each firm.

The market supply curve is the horizontal sum of the supply curves of all firms.

Short-Run Decisions — Equilibrium

When a perfectly competitive industry is in short-run equilibrium, each firm is producing and selling a quantity for which its marginal cost equals the market price.

No firm is motivated to change its output in the short run.

No reason for market price to change in the short run.

The overall market determines the equilibrium price and quantity, (p*, Q*).

The typical firm is a price-taker and produces the profit-maximizing level of output q* at the point where p* = MC.

Short-Run Equilibrium

For a competitive industry, the price and output at which industry demand equals short-run industry supply, and all firms are maximizing their profits. Either profits or losses for individual firms are possible.

Three profit scenarios in the short run

Negative profit.

Zero profit.

Positive profit.

Why?

• In the short run, fixed costs are sunk costs and do not factor into the firm's production decision but still factor into the calculation of total profit.

Long-Run Decisions

In the long run, both the number of firms and the size of each firm's plant are variable.

We begin by assuming that all firms have the same technology and, therefore, the same set of cost curves.

Long-Run Decisions—Entry and Exit

In the short run, firms may earn profit, suffer loss, or break even.

Long-run adjustment occurs through the entry or exit of firms.

Negative economic profit (i.e., economic loss): some firms will exit because capital can earn a better return elsewhere.

Zero economic profit: firms earn as much as they could elsewhere, so there is no incentive to leave or enter.

Positive economic profit: new firms will enter to share in those returns.

Over time, entry and exit push the industry toward zero economic profit.

Holding demand fixed, increase in industry supply → decrease in price.

To maximize profits, both new and old firms adjust output due to the new price.

New firms continue to enter and equilibrium price continues to fall until all firms in the industry are just covering total costs.

The industry settles at a zero-profit equilibrium.

Profits in a competitive industry are a signal for the entry of new firms.

The industry will expand, pushing price down until economic profits fall to zero.

Losses in a competitive industry are a signal for the exit of firms.

The industry will contract, driving the market price up until the remaining firms are just covering their total costs.

How does the market adjust if price is above the shut-down point but firms are making economic losses?

Recall, this can occur when price falls in a certain range:

Shut-Down: p > min. of AVC & Losses: p < min. of ATC

Firms cover variable costs but not fixed costs.

The return on capital is below its opportunity cost.

Exit is gradual (e.g. aging plants and equipment are not replaced).

As firms leave, & industry supply →1 price.

Exit continues until remaining firms can cover all costs.

The industry settles at a zero-profit equilibrium.

Short-Run Decisions — Entry and Exit —- Capital

Exit from an unprofitable industry is not always quick.

The speed of exit depends on how fast capital becomes obsolete or too costly to maintain.

With short-lived capital (e.g., computers), loss-making firms exit quickly.

With long-lived capital (e.g., railways, shipping), equipment is usable for many years.

In both cases, firms continue operating as long as they cover variable costs, despite earning losses.

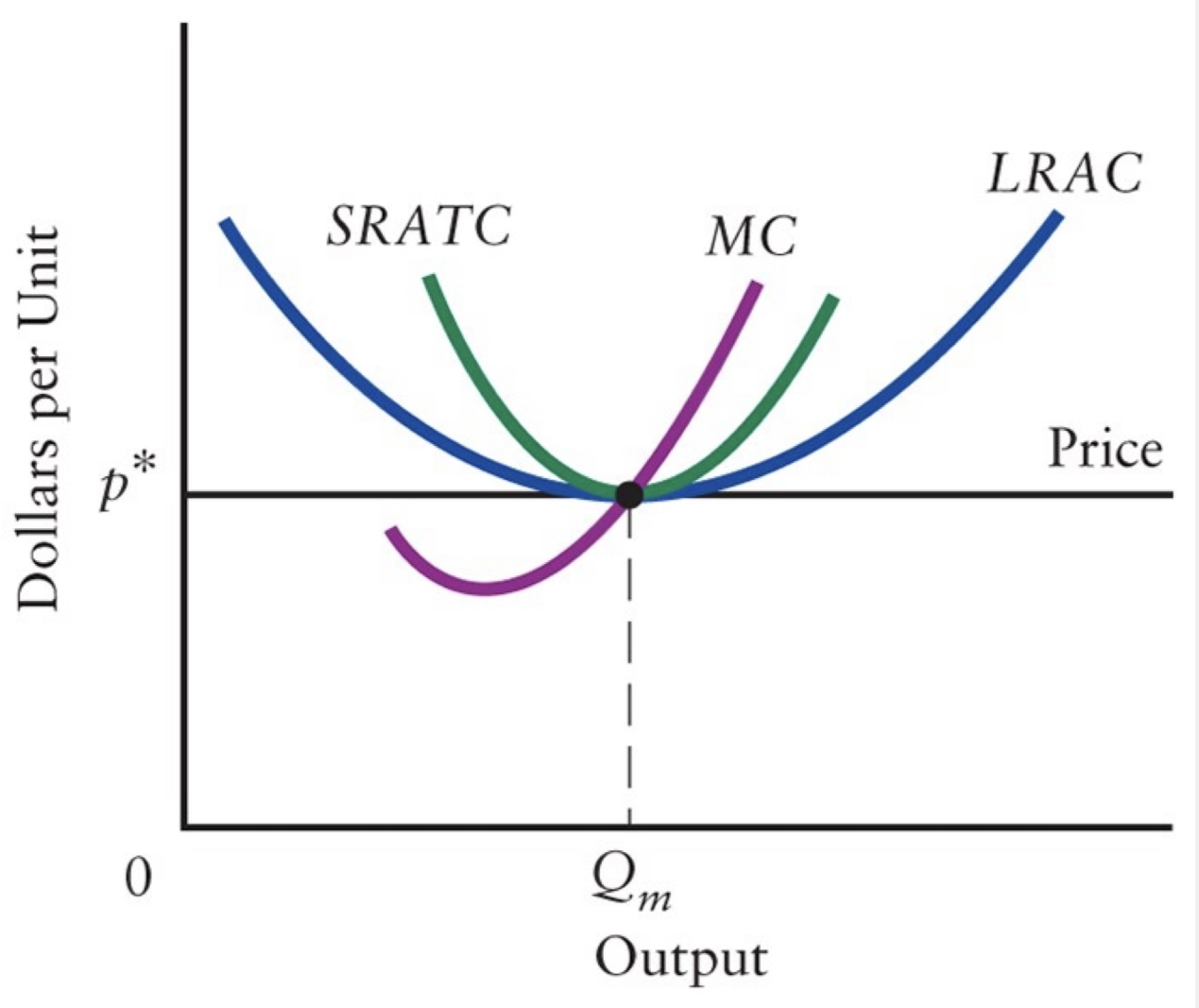

Long-Run Decisions — Equilibrium

Long-run equilibrium of a competitive industry occurs when firms are earning zero profits.

For a competitive firm to maximize long-run profits, it must produce at min. = point on long-run average cost (LRAC) P curve.

At this point, average cost is lowest at-tainable, given limits of known technology and factor prices.

Qm is the minimum efficient scale.

At this point, all long-run equilibrium conditions are satisfied.

Break-Even Price

The price at which a firm is just able to cover all of its costs, including the opportunity cost of capital.

There are four conditions for a competitive industry to be in long-run equilibrium

Existing firms maximize profits, given existing capital (i.e., p = MC).

Existing firms must not be suffering losses.

Existing firms must not be earning profits.

Existing firms must not be able to increase their profits by changing the size of their production facilities.

Therefore, each existing firm must be at the minimum point of its long-run average cost (LRAC) curve.

We now illustrate this point graphically.

Long-Run Decisions — Changes in Technology

If a new technology becomes available:

Existing firms using the old technology cannot easily adopt.

New firms can take advantage of the improved technology to reduce costs and earn economic profits.

As before, as existing firms produce more and new firms enter, Increase in industry supply → decrease in p.

Industries subject to continuous technological change have three common characteristics

Firms of different ages and with different costs co-exist in the industry.

Price is eventually governed by the minimum cost of the lowest-cost (i.e., the newest) firms.

Old firms are discarded (or "mothballed") when the price falls below their minimum average variable costs.

Long-Run Decisions — Declining Industries

What happens when a competitive industry in long-run equilibrium experiences a continual decrease in the demand for its product? E.g., horse-drawn carriages, in-store video rentals, and coal.

For firms, the profit-maximizing response is to continue to operate with existing equipment as long as revenues cover the variable costs of production.

Antiquated equipment is the effect, rather than the cause, of a declining industry.

Governments are often tempted to support declining industries because they are worried about the resulting job losses.

A more effective response is to provide retraining and temporary income-support schemes that cushion the impacts of change.

Intervention that is intended to increase mobility while reducing the social and personal costs of mobility is a viable long-run policy.

Monopoly

A market containing a single firm.

Monopolist

A firm that is the only seller in a market.

Single-Price Monopolist

We look first at a monopolist that charges a single price for its product.

This monopolist's profits, like those of all firms, will depend on the relationship between its costs and its revenues.

Single-Price Monopolist — Revenue

Recall that, in a perfectly competitive market, each firm faced a horizontal demand

curve. This implied AR = MR = p, where p was a fixed market price.By contrast, a monopolist faces a negatively sloped demand curve. Why?

In a monopoly market, there is only one producer.

This firm faces the entire market demand curve for its product.

To study the revenue that a monopolist receives from the sale of its product, economists define three concepts called total, average, and marginal revenue.

Total revenue is the total amount received from sales.

Average revenue is revenue per unit sold, which equals price.

Marginal revenue is the change in total revenue from selling one more unit.

Notice that the definitions for TR, AR and MR are the same as those used to characterize perfectly competitive firms.

As before, a monopolist maximizes total profit by making marginal (i.e., incremental)

production decisions.The key distinction is that MR does not equal p (fixed) for a monopolist.

There are two competing effects

Gain from revenue of the new units sold.

Loss from price reduction of the units already being sold.

This 'loss' component means MR is always less than AR.

Recall the two general rules about profit maximization

Firm should produce only if price (average revenue) exceeds average variable cost.

If the firm does produce, it should produce a level of output such that marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

• These rules also apply to a profit-maximizing monopolist, except in this setting the firm has control over both quantity and price.

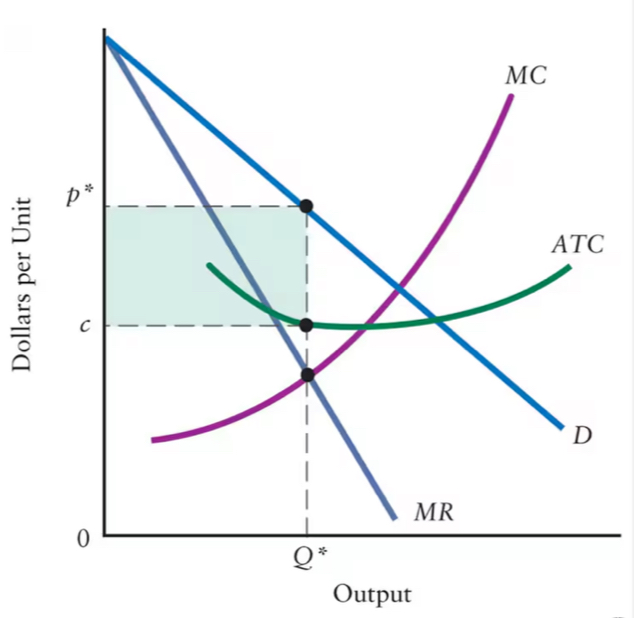

Single-Price Monopolist — Profit Maximization

For a profit-maximizing monopolist, price exceeds marginal cost.

As in perfect competition, nothing guarantees that a monopolist will make positive profits in the short run, but if it suffers persistent losses, it will eventually go out of business.

Demand curve is consumers' max. willingness to pay for a given quantity.

Monopoly price is p*. This means average revenue per unit is AR = p*.

The average total cost is ATC = c.

In equilibrium, the monopolist earns a positive profit.

Single-Price Monopolist — No Supply Curve

Recall, the supply curve is the amount a firm is willing to supply at different prices.

In describing the monopolist's profit-maximizing behaviour, we did not introduce the concept of a supply curve.

A monopolist does not have a supply curve because it is not a price taker.

Instead, it chooses its profit-maximizing price-quantity combination from among the possible combinations on the market demand curve.

Single-Price Monopolist — Firm and Industry

Because the monopolist is the only producer in an industry, there is no need for a separate discussion about the firm and the industry.

The monopolist is the industry.

Thus, the short-run, profit-maximizing position of the firm is also the short-run equilibrium for the industry.

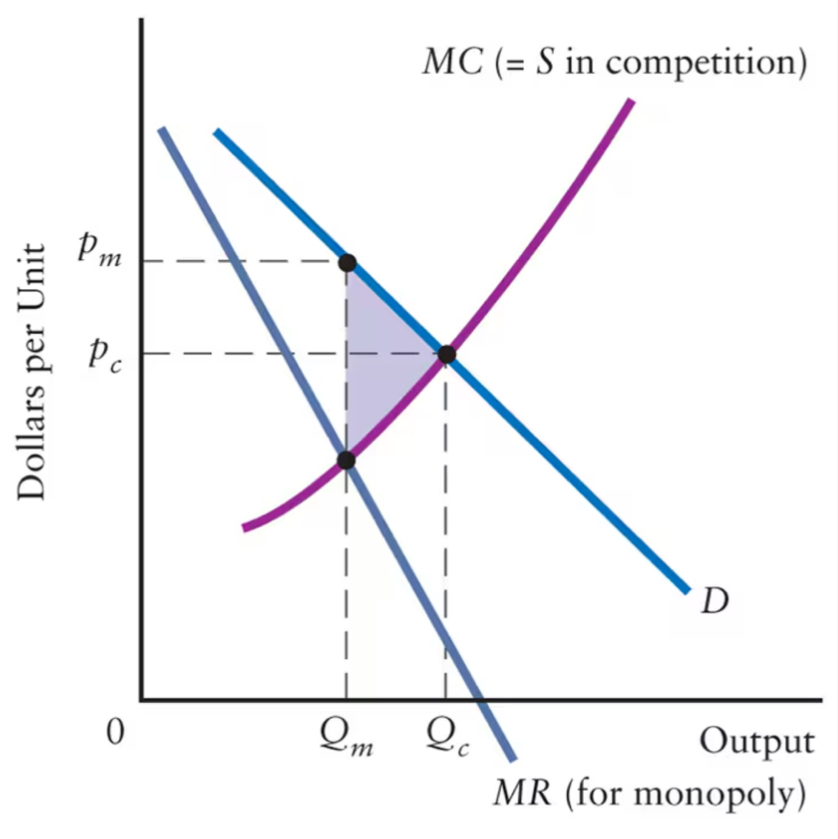

Single-Price Monopolist — Inefficiency

Why are monopolies rare and highly regulated?

Why are cartels illegal?

The comparison of monopoly with perfect competition is important. Our theory provides a basis for understanding the value of competition (i.e., opportunity cost of non-competition).

Monopolist chooses the price-quantity combination to maximize its private net benefit (i.e., profit).

How does it compare to perfect competition, which we know to be a socially efficient allocation of resources?

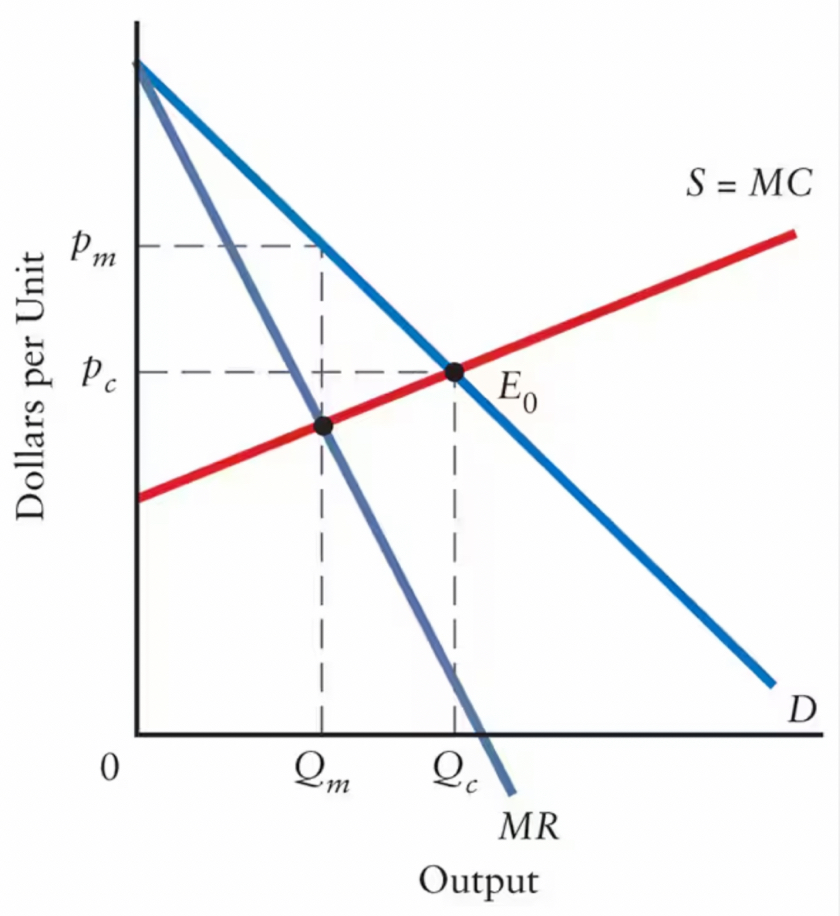

If the monopolist were a price-taking firm in a competitive market, then S = MC (for prices above shut-down).

Competitive equilibrium is Pc, Qc.

Monopolist restricts output below the competitive level and creates loss of economic surplus for society (i.e.,"deadweight loss").

• Monopoly → market inefficiency.

Single-Price Monopolist — Why Monopolies are Rare

When they do exist, they tend to earn very large profits, which quickly attracts other firms into the industry.

Monopolist is able to persist in rare cases where there are:

Natural entry barriers.

Created entry barriers.

Single-Price Monopolist — Natural Entry Barriers

Limited access to key natural resources.

Network effects (e.g., social media).

In industries with very high fixed costs, a firm's minimum efficient scale may correspond to a very high level of output.

Competition may not be feasible (e.g., competition in electrical power transmission would require two sets of power lines spanning a given region).

Natural Monopoly

An industry characterized by economies of scale sufficiently large that only one firm can cover its costs while producing at its minimum efficient scale.

Single-Price Monopolist — Created Entry Barriers

Patent laws.

Charter or franchise that prohibits competition (e.g., Canada Post).

Threat of force or sabotage.

Threat of price-cutting.

Lessons from History 10-1

In the very long run, technology changes. New ways of producing old products are invented, and new products are created to satisfy both familiar and new wants.

Entry barriers are often circumvented by the innovation of production processes and the development of new goods and services.

Quill pen → still-nibbed pen → fountain pen → ballpoint pen.

Silent film → talkies → colour film.

Sailing vessel → steamship → airplane.

Craft production → assembly line.

Linotype → computer typesetting → laser printing.

Single-Price Monopolist — Creative Destruction

Creative destruction refers to the elimination of one product by a superior one.

It reflects new firms' abilities to circumvent entry barriers that would otherwise permit existing firms to earn high profits in the long run.

Because creative destruction thrives on innovation, the existence of high profits is a major incentive to economic growth.

Destruction implies firm closures and job losses.

Governments need to be careful not to prop up dying firms and industries for politically-motivated reasons.

Cartels and Monopoly Power

So far in our discussion, a monopoly has meant that there is only one firm in an industry.

Another way a monopoly can arise is for several firms in an industry to agree to cooperate with one another, eliminating competition among themselves.

Price fixing.

Market allocation.

Restricting supply.

Bid-rigging.

Wage-fixing.

Canadian competition policy (and U.S. anti-trust policy) has been effective at preventing the creation of large cartels that would otherwise possess considerable market power.

The best current examples of cartels are ones that operate in global markets and are supported by national governments.

E.g., Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

E.g., Diamond cartel controlled by DeBeers.

Cartel

An organization of producers who agree to act as a single seller in order to maximize joint profits.

Cartels and Monopoly Power — Effects

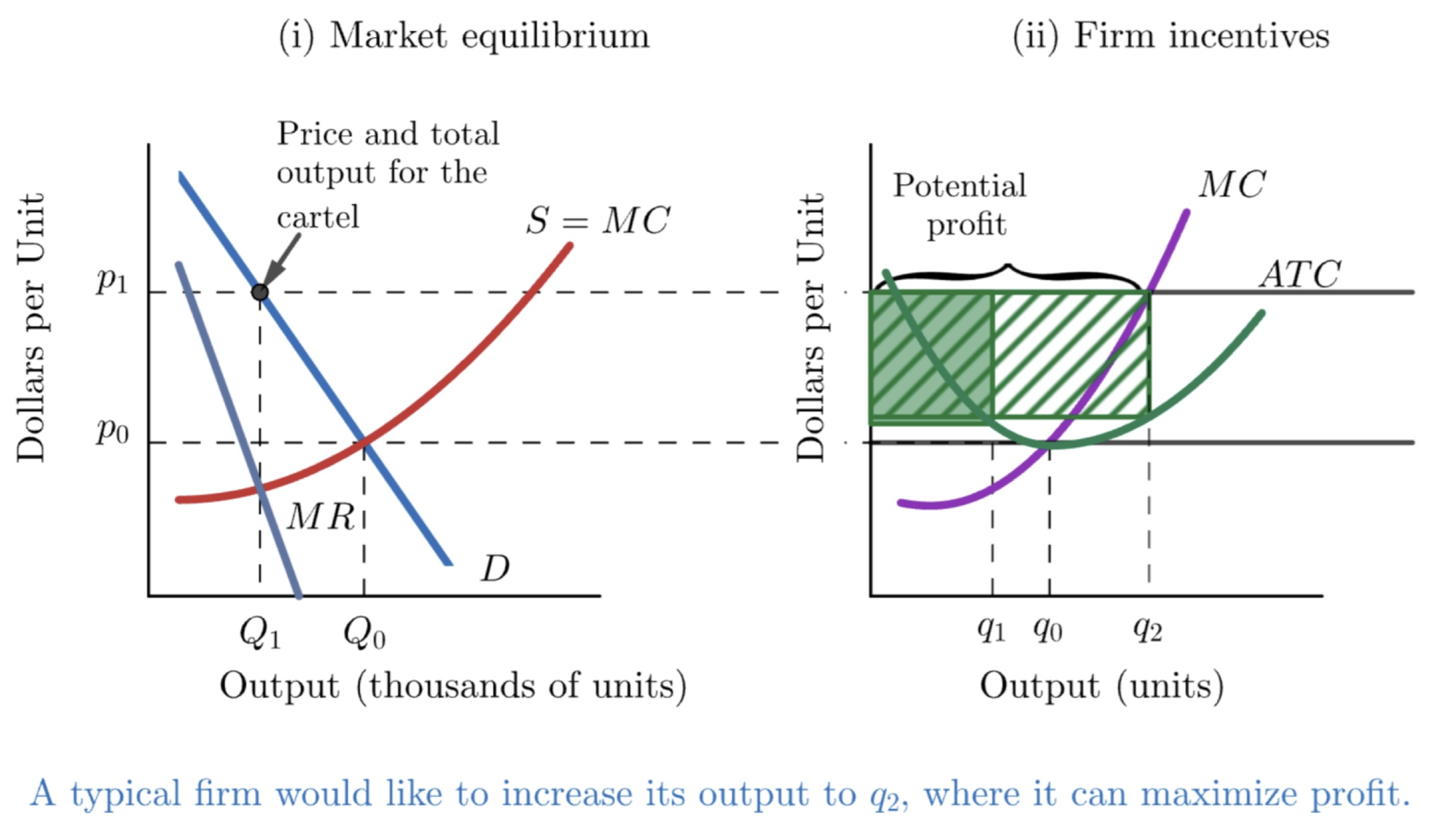

If all firms in a competitive industry come together to form a cartel, they must recognize the effect their joint output has on price.

Must agree to restrict industry output to the level that maximizes their joint profits.

The incentive for firms to form a cartel lies in the cartel's ability to restrict output, thereby raising price and increasing profits.

If all firms in the industry form a cartel, profits can be increased by reducing output, Qc → Qm.

Profit-maximizing cartelization of a competitive industry will reduce output and raise price relative to the pertectly competitive levels.

Cartels and Monopoly Power — Problems That Cartels Face

Cartels encounter two characteristic problems:

Ensuring that members follow the behaviour that will maximize the cartel members' joint profits.

Preventing the profits from being eroded by the entry of new firms.

When a cartel reduces output and succeeds in raising the market price, each firm has an incentive to cheat and increase its output to gain from the high price.

Holding constant the behaviour of all other firms, the one cheating firm has no effect on industry output and market price remains high.

The same incentive to cheat exists for all firms.

Cartels tend to be unstable because of the incentives for individual firms to violate the output restrictions needed to sustain the joint-profit-maximizing (monopoly) price.

Cartels tend to be unstable because of the incentives for individual firms to violate the output restrictions needed to sustain the joint-profit-maximizing (monopoly) price.

E.g., OPEC was formed in the 1970s but almost collapsed in the 1980s following several years of sluggish world demand for oil when some OPEC members increased their output in an effort to generate more income.

Authorities rely on legal incentives to detect and investigate cartels.

Majority of prosecutions begin with an application for immunity.

Cartel members are often untrustworthy. After all, they are breaking the law to begin with!

Monopoly Introduction

Perfect competition is one end of the spectrum of market structures.

At the other end is monopoly.

When the output of an entire industry is produced by a single firm, we call that firm a monopolist or a monopoly firm.

A perfectly competitive firm has no market power, which means it has no ability to influence the market-determined price.

A monopolist, on the other hand, has the maximum possible market power because it is the only firm in its industry.

These two extremes of behaviour are useful for economists in their study of market structures.

Examples of monopoly are rare, partly because when they do exist their high profits attract entry by rival firms, at which point they cease to be monopolists.

When a monopoly is able to persist, it is often because it has been granted some special protection by government, as in the case of electric utilities (often owned by provincial governments) or prescription drugs (which are often protected by patents).

Firms can also band together in order to behave more like a monopolist.

Cartel agreements (i.e., price fixing, market allocation, restricting supply, bid-rigging, and wage-fixing) are illegal.

Justification is not that we value consumer welfare more than firm profits.

Rather, competition is preferred because competitive markets lead to more efficient outcomes than monopoly markets.