Graphs

1/56

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

57 Terms

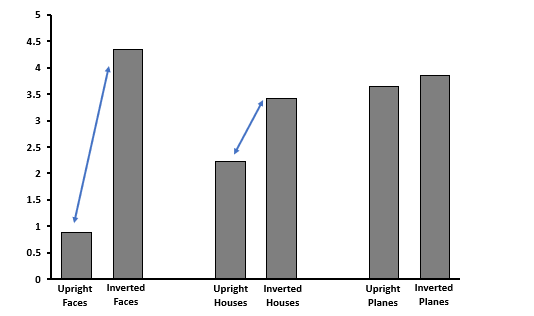

Yin (1969) Exp 1

found a robust inversion effect for faces that was larger than that for other sets of stimuli supporting the specificity account of face recognition mechanisms

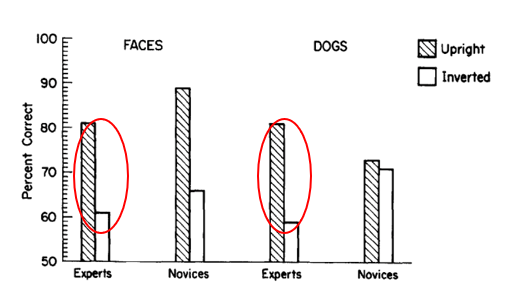

Diamond & Carey (1986)

found a robust inversion effect for dog images as that for faces (when observes were experts dog breeders) supporting the expertise account of face recognition mechanisms

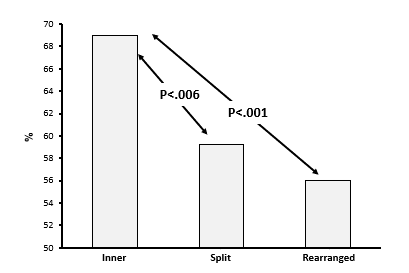

Parr & Heintz (2006) Exp1

The inversion effect suggests that chimps like humans, show face configural processing

Parr & Heintz (2006) Exp2

shows significant impairments when faces were manipulated to disrupt second-order relations, both the split feature trials and the split plus rearranged feature trials.

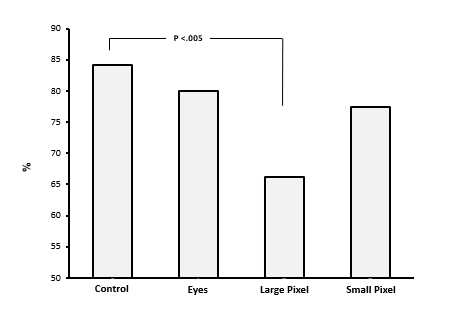

Parr & Heintz (2006) Exp3

pixelating faces using a large radius filter, affecting both first- and second-order relations, affects subjects’ recognition performance

Gauthier et al., (1999)

Similar FFA activation for faces and Greebles for Greeble experts supporting the expertise account of face recognition mechanisms

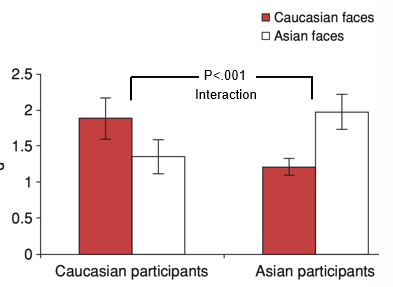

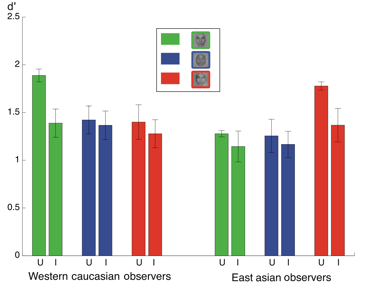

Michel et al (2006)

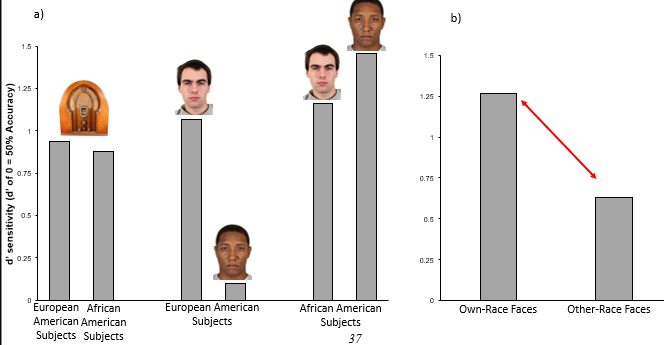

Golby et al (2001)

showed superior recognition memory for same-race compared to other-race faces

Golby et al (2001)

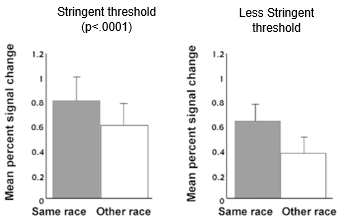

revealed that compared to other-race faces, same-race faces were associated with greater activation in the FFA previously identified as areas of initial specialization for the perception of faces.

FFA was more active for same- race than for other-race faces in at least 84% of participants.

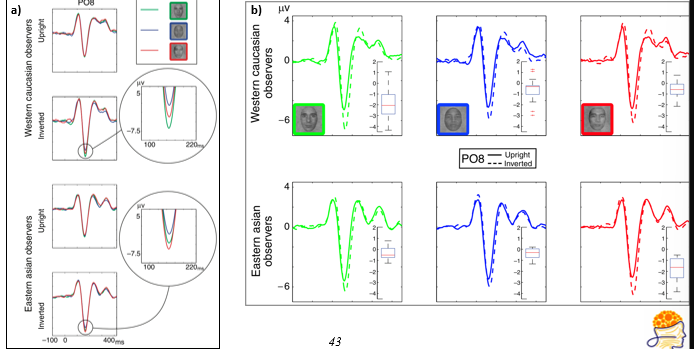

Vizioli et al (2010)

Western Caucasian & East Asian observers were more accurate at recognizing same-race compared to other-race faces

This was indexed by the larger inversion effect recorded for same vs other race faces.

Vizioli et al (2010)

The amplitude of the face inversion effect was largest for own-race vs other-race faces.

The reduce behavioural and N170 inversion effect for other-race faces could be due to reduce expertise at scrutinizing configural information.

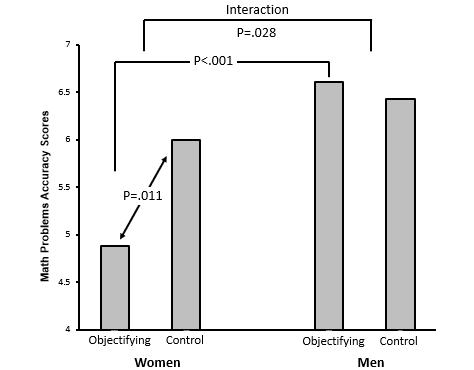

Gervais et al (2011) maths scores

being objectified damages women’s maths score`

after being objectified men increase maths score

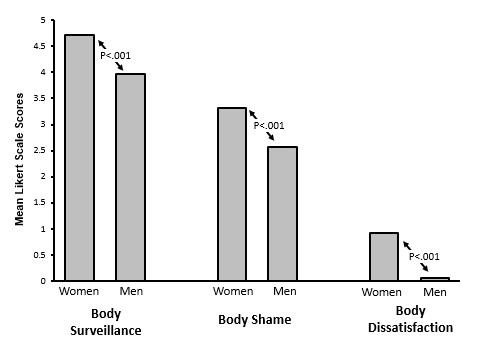

Gervais et al (2011) gaze affecting women’s body

Objectifying gaze affected women’s body self-perception indexed by measures of body surveillance, body shame, and body dissatisfaction

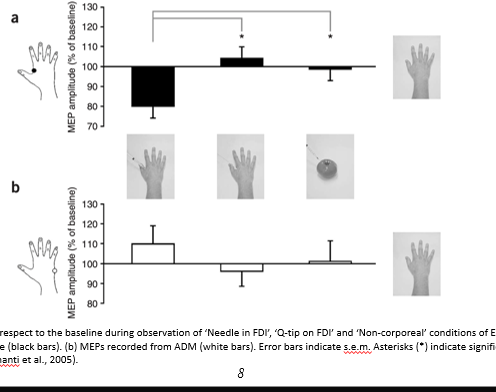

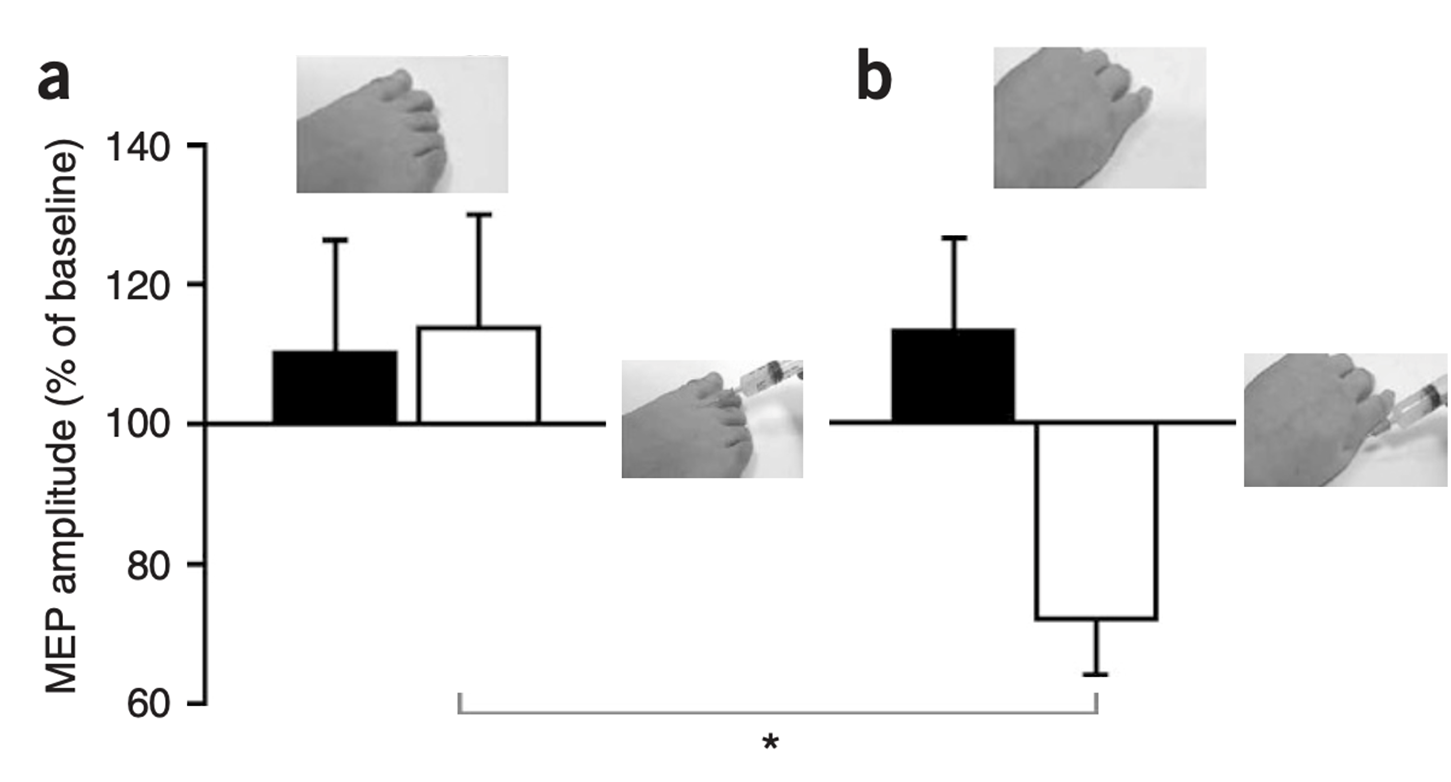

Avenanti et al (2005) exp1

Decreased muscle activation (i.e., lower MEPs) in response to observing pain compared to non-painful or neutral conditions.

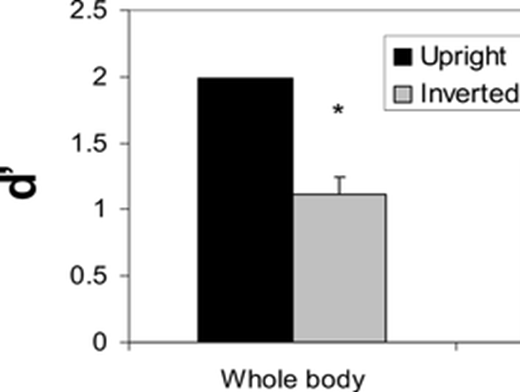

Reed et al (2003)

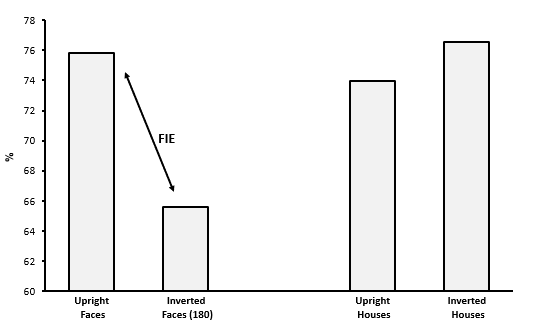

Inversion disrupts our ability to exploit configural information

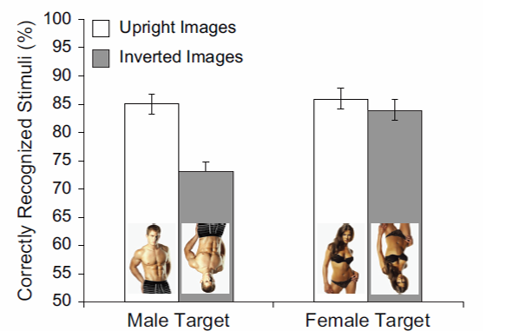

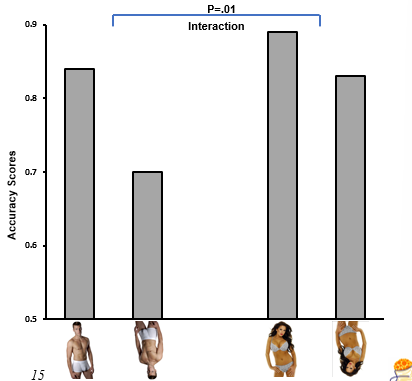

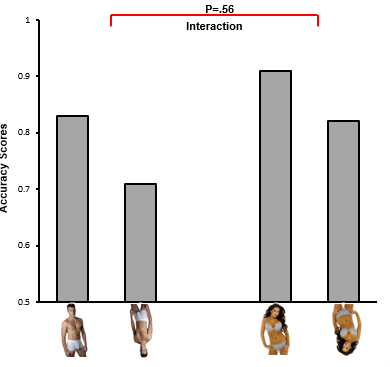

Bernard et al (2012)

Both male & female showed a reduced inversion effect for sexualized women → perceiving them as object-like / featural processing

Both male & female P showed a robust inversion effect for sexualized men perceiving them as face/body-like / configural processing

Berard et al (2015) Exp1

replicated results of 2012 study

larger inversion effect for men

small effect for women = processed like objects

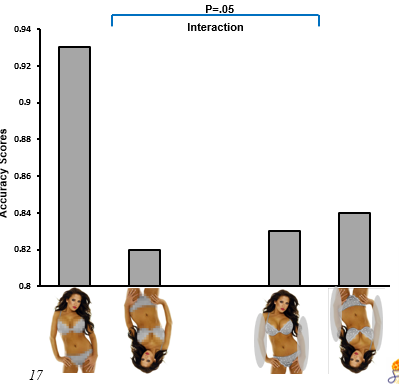

Berard et al (2015) Exp2a

Pixelating sexual body parts eliminated difference in configural processing between sexualized female & male bodies.

P showed a normal inversion effect (harder to recognize inverted images) for both women and men.

No difference in recognition performance between sexualized female and male bodies after pixelation

Berard et al (2015) Exp2B

pixelating reduces objectification

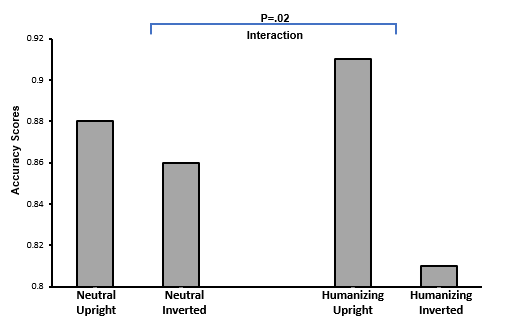

Bernard et al (2015) Exp 3

humanising allowed for inversion effect preving objectification

both men & women show reduced IE in response to sexualised images of women

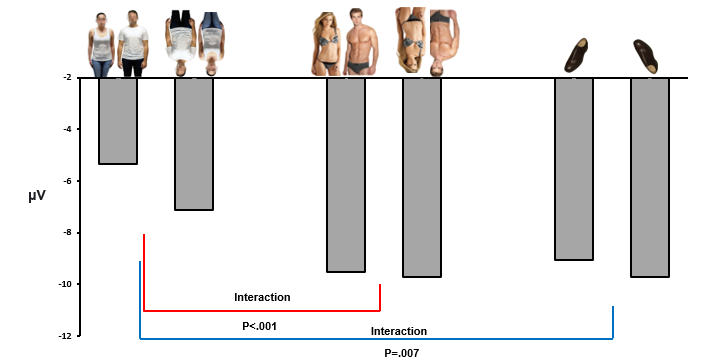

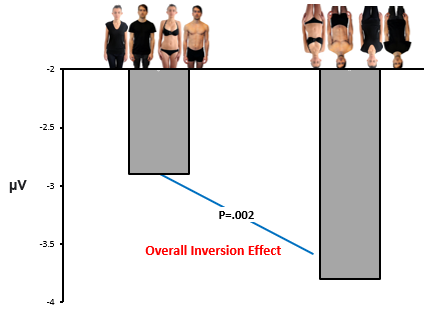

Bernard et al (2018)

larger n170 amplitude for

female bodies compared to male

sexualsied bodies compared to non

inverted images compared to upright

lack of inversion effect for sexualised bodies suggest reduced configural processing

women more likely to be portrayed as sexual & when non sexualised, are less likely to be processes holsitically

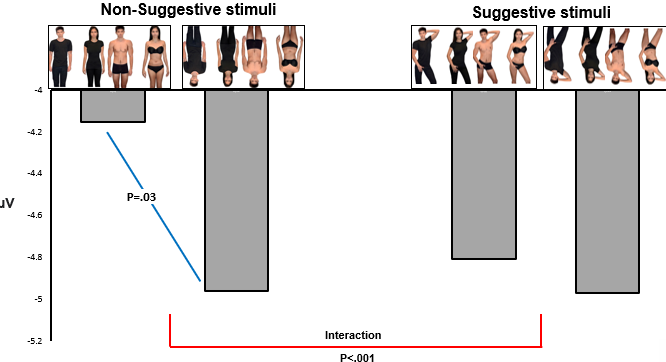

Bernard et al (2019) Exp1

skin exposure does not necessarily cause objectification;

bodies were processed holistically whether they had a lot of skin showing or not.

Bernard et al (2019) Exp2

Posture, not amount of skin exposure, is the key driver of cognitive objectification.

Suggestive postures lead to treating bodies more like objects (less holistic/configural processing).

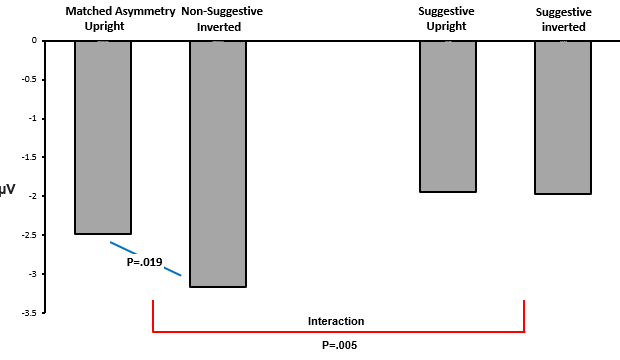

Bernard et al (2019) Exp3

Bodies in suggestive postures are processed less configurally and are more objectified

this effect is driven by the suggestiveness of the posture, not by differences in body shape or asymmetry

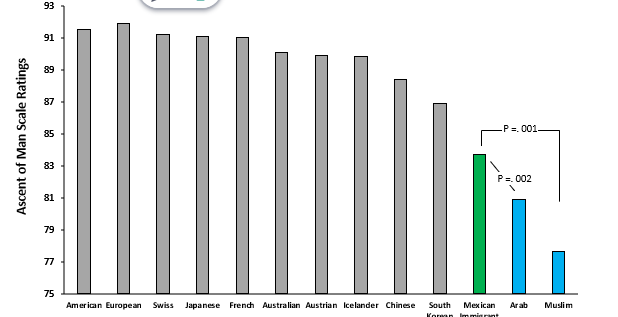

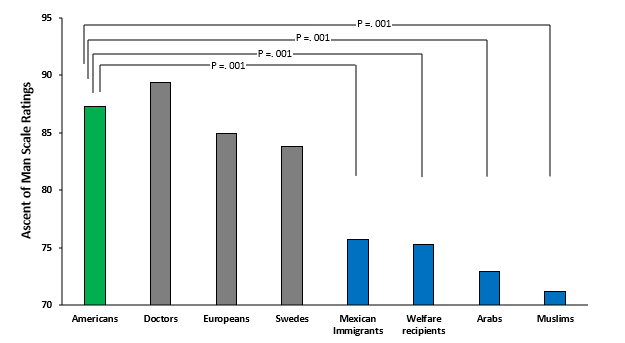

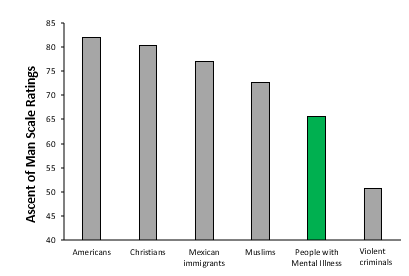

Kteily et al et al (2015)’s Exp1

Arabs & muslims were rated as signfic less evolved than other groups

american & europeans were rated significantly more evolved

Kteily et al et al (2015)’s Exp1a

uses personality & empathy test

doctors & americans seen as more evolved than mexican immigrants, welfare recipients & muslims

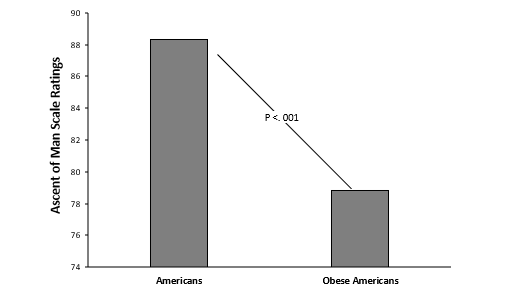

Kersbergen & Robinsons (2019) Exp1

obese americans were considered less evolved than americans

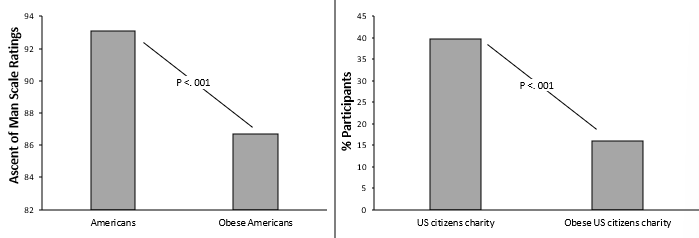

Kersbergen & Robinsons (2019) Exp2

Us citizen condition 39% of p donated

for obese us charity 16%

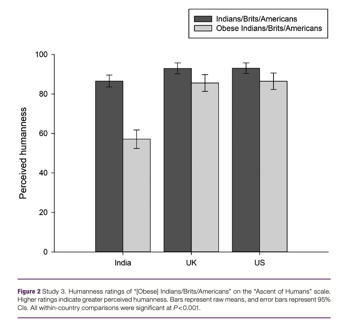

Kersbergen & Robinsons (2019) Exp3

obese individuals were dehumanised

indians had larger dehumanisation

more likely to reduce animal suffering

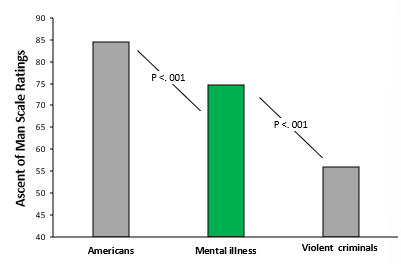

Boysen et al (2020) Exp1

mental illness is dehumanised

over ½ SD separated rationing of p w/MI from americans

less dehumanised than violent criminals but more than americans

Boysen et al (2020) Exp3

blatant dehumanisation most prevalent for violent criminals then ppl w/MI & americans

Mi is highly stigmatised

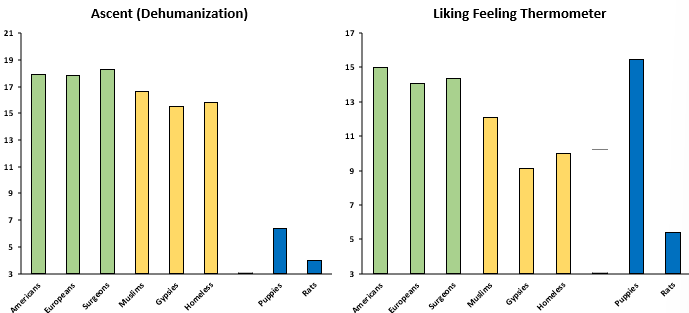

Bruneau et al (2018)

Low-status groups are dehumanised similarly to animals, with specific brain regions (IPC, IFC, dMPC) showing no distinction between animals and dehumanised humans.

IFC helps drive this dehumanisation.

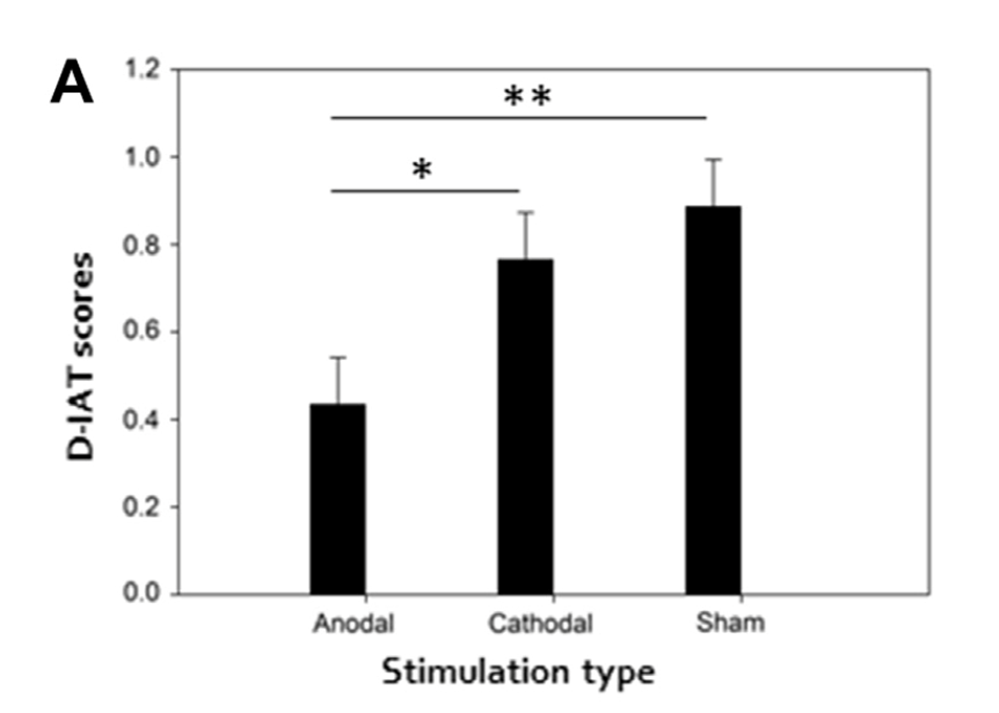

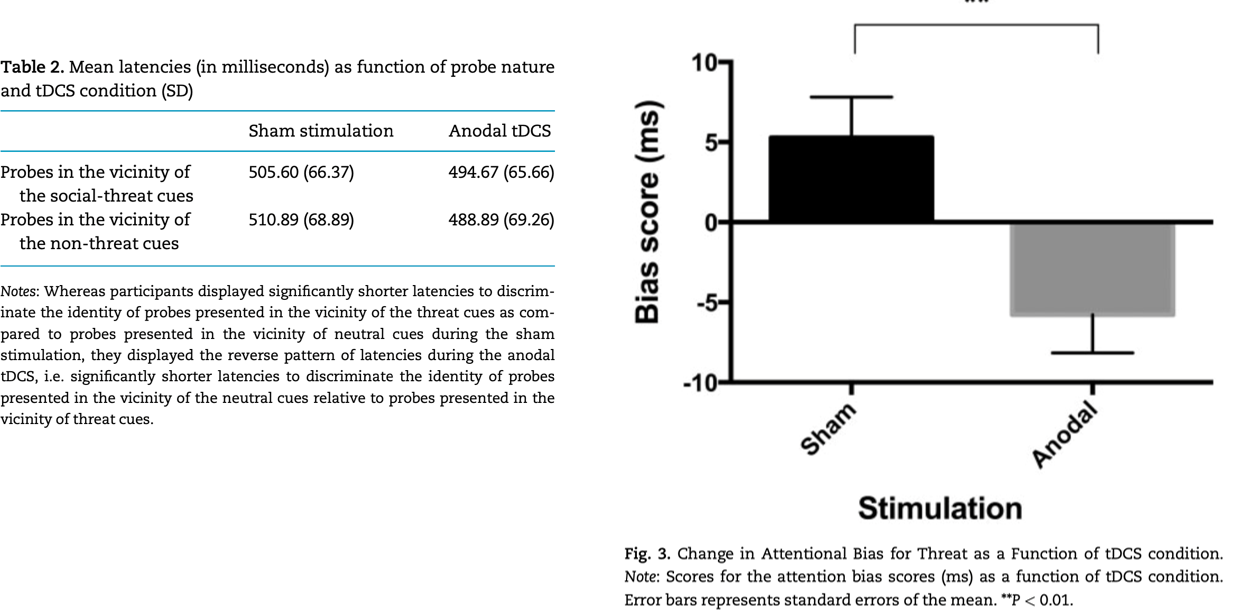

Sellaro et al (2015)

congruent trial = faster RT due to alignment w/attuitude

incongruent trial = slower RT suggesting automatic associations even w/out explicit prejudice

Anodal stimulation significantly reduced implicit bias

reduction of D-IAT scores suggests MPFC is recruited to control for implicit bias

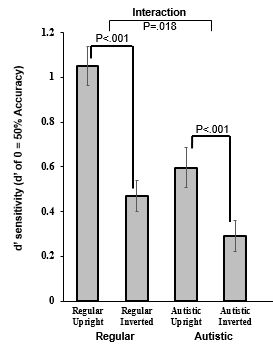

Civile et al (2019) Exp1

stronger FIE for regular faces

weaker inversion effect for autistic faces

labelling faces as autistic results in configural processing

Civile et al (2019) Exp2

showed larger inversion effect after humanising info about faces labelled as autistic

Makumel et al (2010)

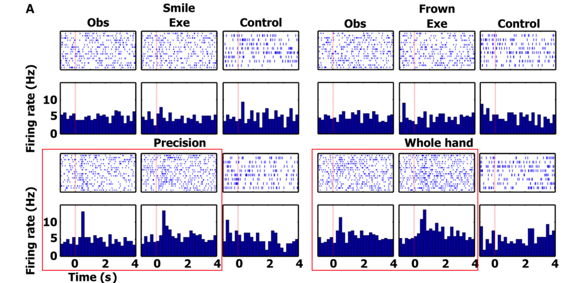

hand cued p to perfrom full hand grasp

p smiled or formed depending on cue

suggest existence of multiple systems w/neural

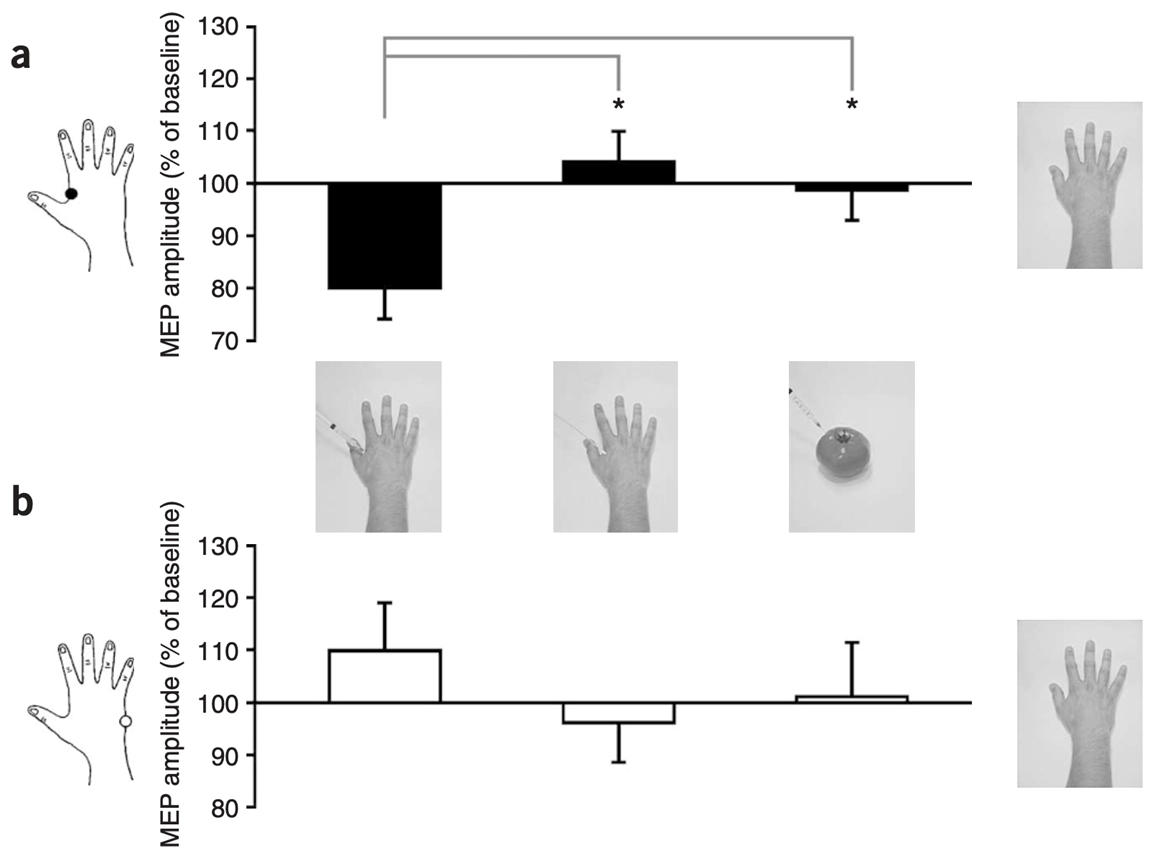

Avenanti et al (2005) exp1

decreased motor excitability during observation of needle in model’s hand

Inhibitory sensorimotor response → decreased muscle activation in response to observing pain

Higher MEP amplitude w/Q-tip on hand

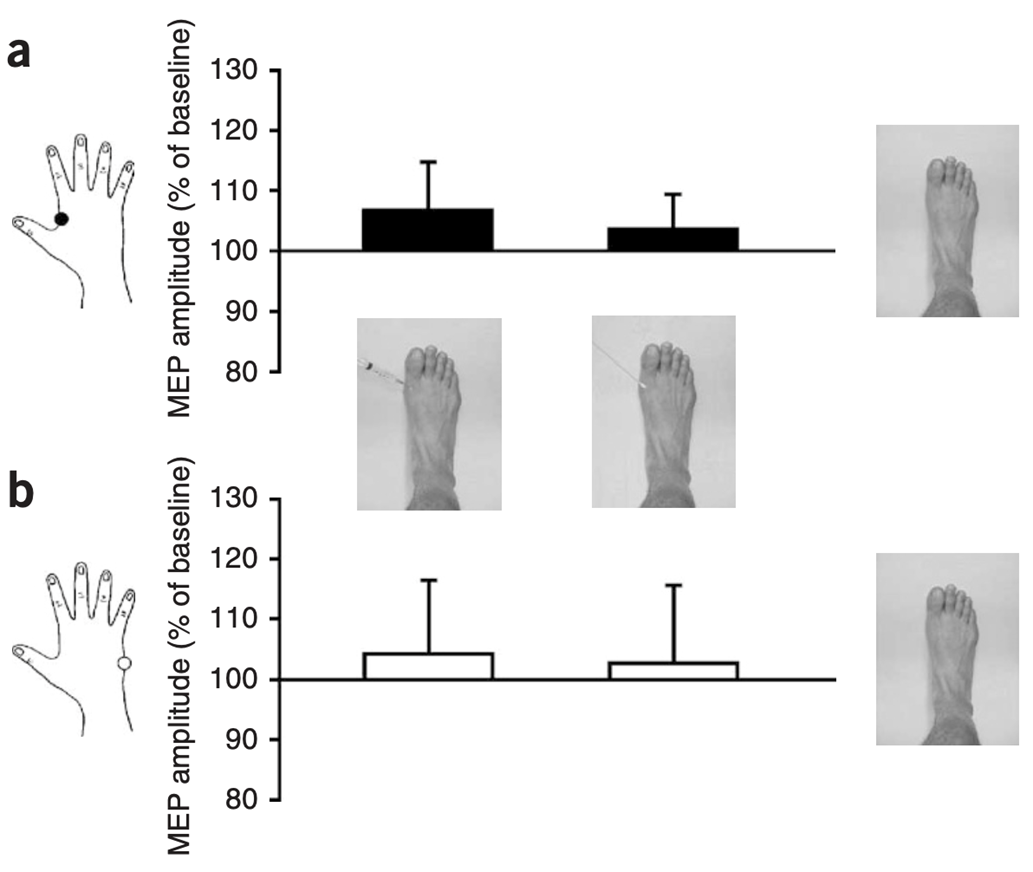

Avenanti et al (2005) exp2

no significant modulation of MEP amplitude recorded from FDI or ADM muscles when observers viewed foot stimulations

watching pain stimulation didn’t elecit MEPs

showing specific activation

Avenanti et al (2005) exp3

results were consistent w/selectivity in ½

MEP recorded from ADM muscle during needled = decreased muscle activation

anatomically specific pain response → doesn’t affect MEPs in unrelated muscles

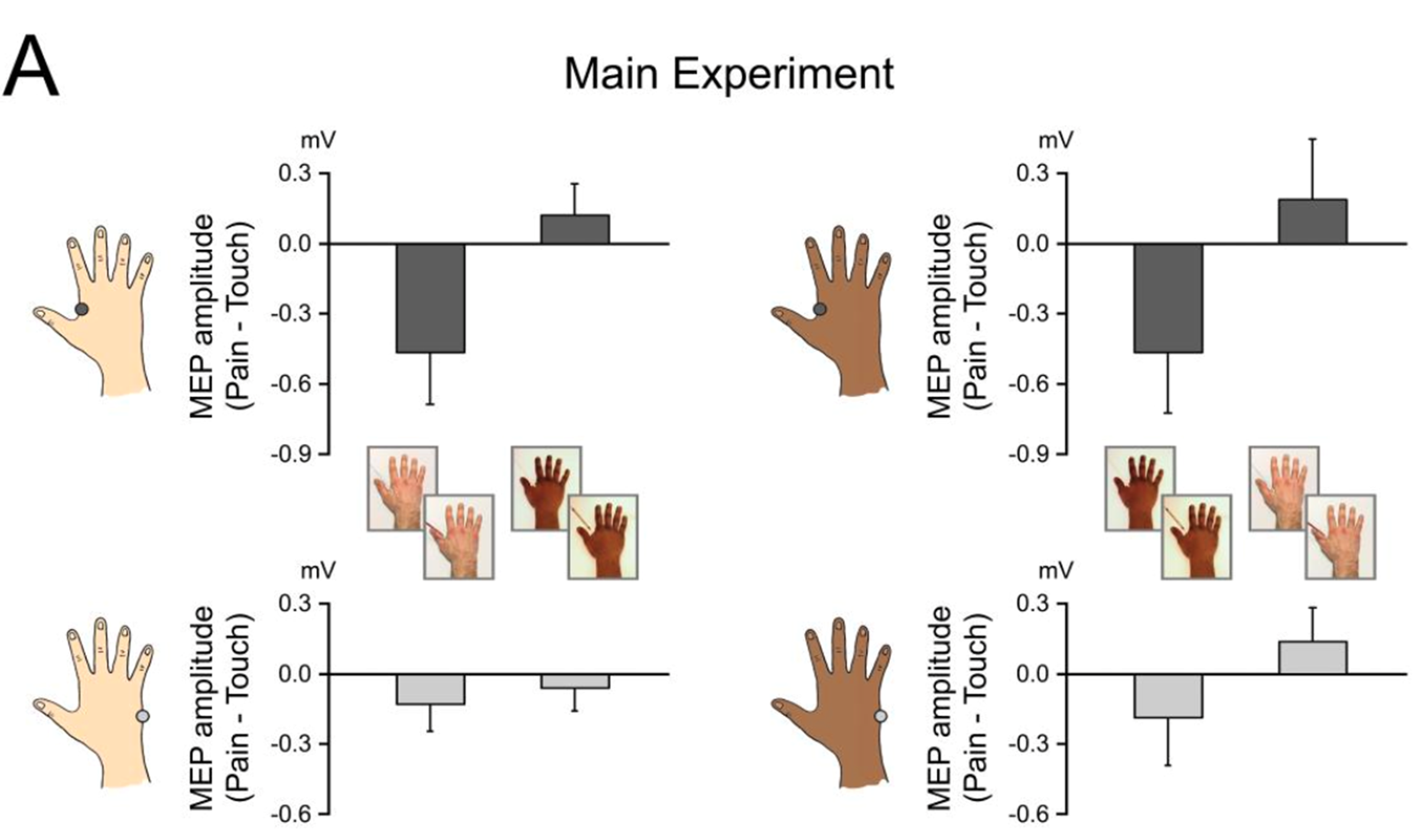

Aventant et al (2010)

Watching painful stimuli applied to ingroup (same-race) models led to a significant reduction in MEPs from the FDI muscle

muscle corresponding to the observed pain site.

No MEP reduction was found when watching outgroup (other-race) models in pain.

No differences were found in the ADM muscle (a control muscle not involved in the pain), confirming muscle specificity.

P’s race (Black or White) did not influence the results — both groups showed similar patterns.

suggests that sensorimotor empathy is both muscle-specific and socially biased, showing stronger neural mirroring for ingroup pain.

Aventant et al (2010) violet skin effect

Painful stimulation to ingroup hands led to a significant reduction in MEP amplitude in the FDI muscle (the observed pain site).

No significant MEP reduction was found for the ADM muscle (not stimulated), regardless of group — confirming muscle-specificity.

A mixed-model ANOVA showed no interaction or main effect of participant race — both Black and White participants showed similar MEP modulation.

MEP reduction was greater for:

Ingroup models > Outgroup

Violet model > Outgroup

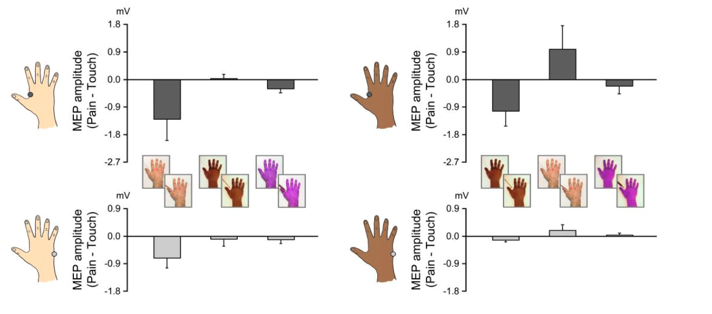

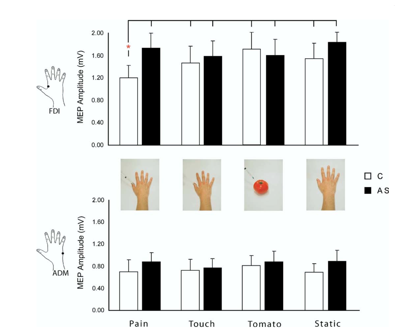

Mino-Palvello et al (2008) AS & empathy

Individuals w/AS showed no differences in sensorimotor empathy across the stimuli presented

neurotypical had a large decrease in MEP for pain only → showing empathy for pain

AS didn't significantly show reduced MEP for pain

didnt show the index of empathy

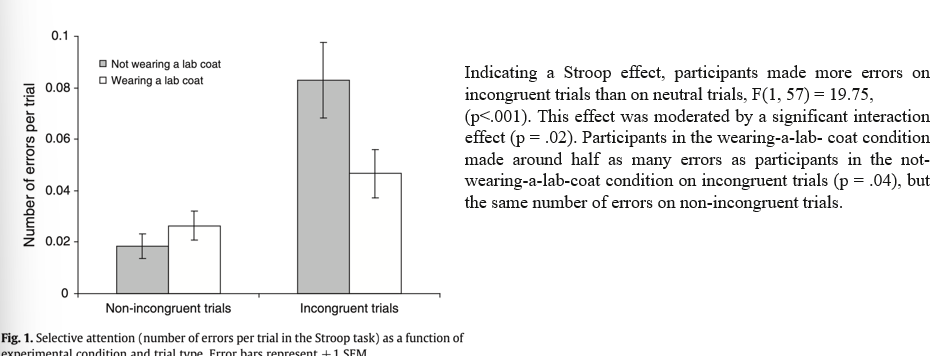

Adam & Galinksy (2012) exp1 results

P who wore a lab coat made fewer errors on incongruent trials than those who did not wear a lab coat

those wearing a lab coat made about half as many errors as those not

No difference in errors was found between the two groups on non-incongruent trials.

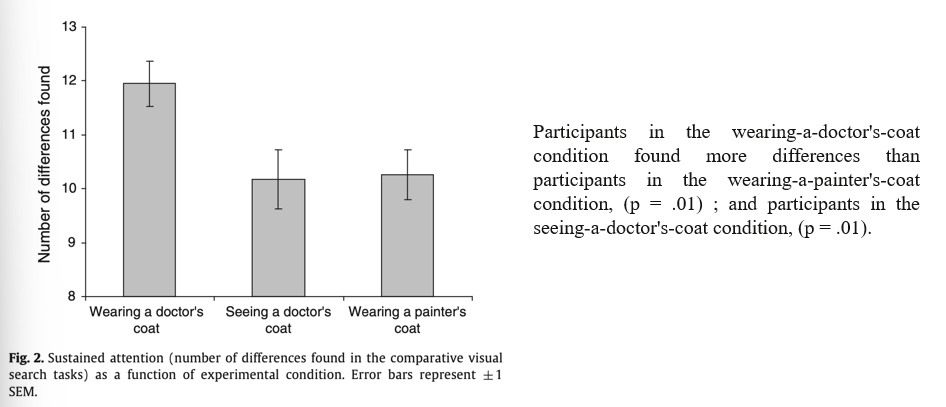

Adam & Galinksy (2012) exp2 results

P who wore a doctor’s coat found more differences than those who wore a painter’s coat or only saw a doctor's coat

no significant difference in performance between P who saw a doctor’s coat & those who wore a painter’s coat.

Wearing a doctor’s coat may have enhanced sustained attention, possibly because of the symbolic association with careful, detail-oriented professions (like medicine).

Simply seeing a doctor’s coat was not enough to boost attention → wearing it was necessary to see the benefits.

Wearing a painter’s coat did not produce the same effect, suggesting that the meaning of the clothing matters in cognitive performance.

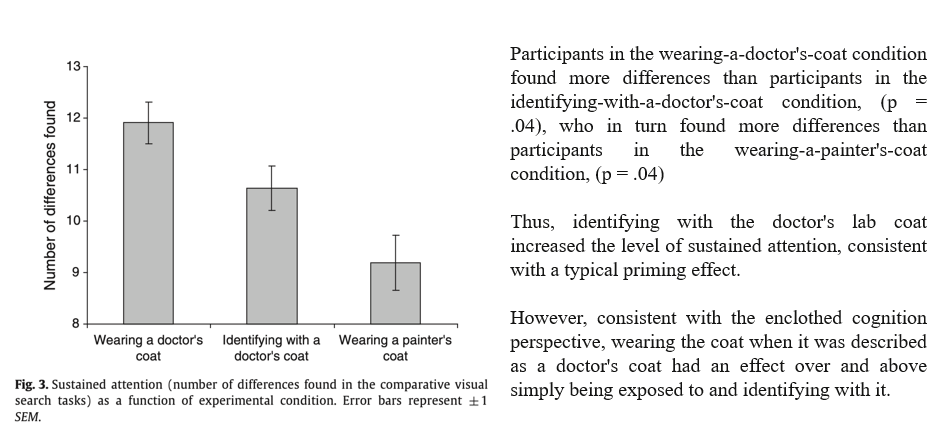

Adam & Galinksy (2012) exp3 results

P who wore a doctor’s coat, found significantly more differences than those who identified with a doctor's coat → simply identifying with the idea of a doctor's coat wasn’t as effective as actually wearing it

P in the identifying-with-a-doctor’s-coat condition found more differences than those wearing a painter’s coat → suggests that priming did increase attention somewhat, but not as much as actually wearing it.

P in the painter’s coat condition performed the worst, reinforcing the idea that the symbolic meaning of clothing matters.

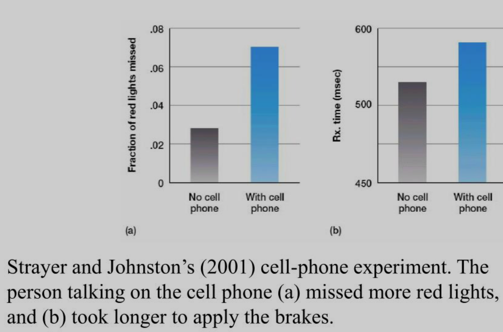

example of divided attention (Strayer & Johnston, 2001)

a simulated driving task → allowed them to examine the effects of engaging in cell phone conversation on various aspects of driving performance

results showed P who were involved in cell phone conversations were more prone to missing stimulated traffic signals & exhibited slower reaction times

degree of impairment was consistent regardless of whether phone was used in a handheld or hands free mode

cell phone convo disrupts driving performance by diverting attention to a cognitively engaging task that competes w/mental focus required of safe driving

illustrates dangers of multitasking within complex environments

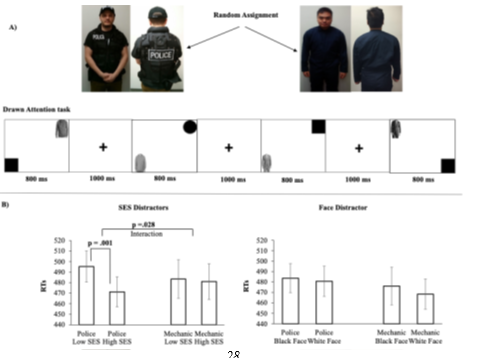

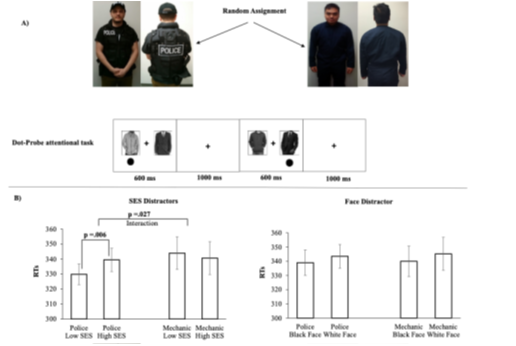

Civile & Obhi (2017) exp 1

p wearing uniforms had slower RT overall (poorer task performance)

suggests that wearing uniform affects cognitive processing

no significant difference between black/white faces

distractor not race

implies uniform was responsible for reduced performance

wearing uniform primes wearer to be more vigilant leading to greater distraction

Civile & Obhi (2017) exp 2

faster RT in congruent trials suggest attention was already directed there

attentional bias more attentions drawn

p wearing police uniform showed attentional bias for hoodies (quicker RT if dot behind)

no significant attentional bias between back/white faces

uniform increased attentional capture by clothes associated w/perceived threat

Civile & Obhi (2017) exp 3

attentional bias towards hoodies (Low SES) only occurred when p wore police uniform

attentional bias based on perceived social class

simply seeing uniform had no effect

no difference between black vs white

police uniforms & bias towards to lower SES are linked

supports enclothed cognition

Heeren et al (2017) results

show attentional bias for social threat

shown in probe detection/discrimination task

faster response to problem replacing threat stimuli

not present in non-anxious

suggest cognitive mechanisms maintains anxiety

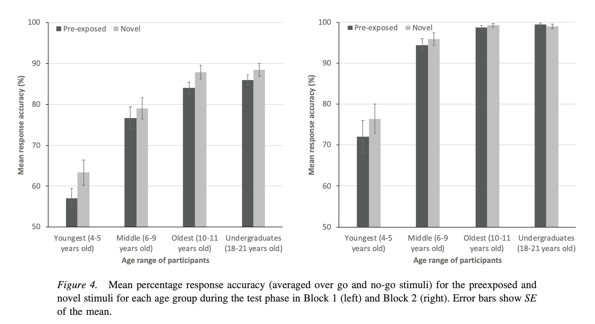

Mclaren et al (2021)

Young children show latent inhibition from simple pre-exposure, consistent with slower learning.

Older groups do not, suggesting developmental changes in attentional control or learning systems.

Supports the idea that experience with stimuli can interfere with learning, especially in early development.

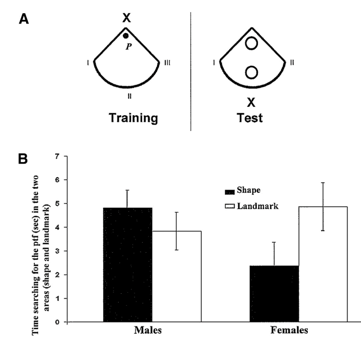

Rodriguez exp 1 (2010)

Female rats spent more time in the landmark area than males.

This indicates that females relied more on the visual landmark, while

Males tended to rely more on the geometric shape of the pool.

There is a sex difference in spatial cue preference:

Females → prefer landmarks

Males → prefer geometric configuration

Rodriguez exp 2 (2010)

Females showed stronger preference for the landmark cue.

Both sexes successfully used both types of cues when tested individually

difference is preferential, not an inability – not an innate limitation.

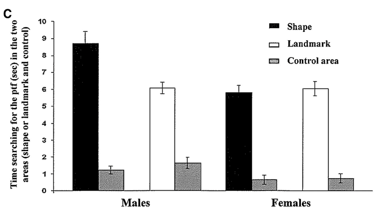

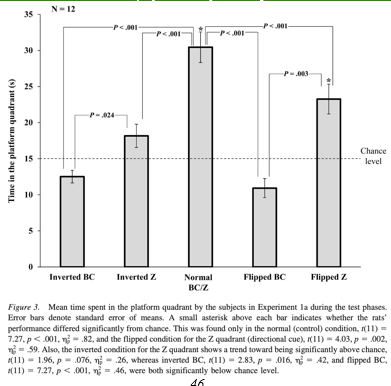

Civile & Chamizo et al (2014) exp 1

Configural arrangement of landmarks is crucial for spatial memory.

Males navigated better overall

flipping near landmarks disrupted performance more than flipping far ones

Civile & Chamizo et al (2014) exp 2

performance was above chance in control & flipped far

rats in inverted did not perform well → disrupted navigation

spent less time in z due to confusion

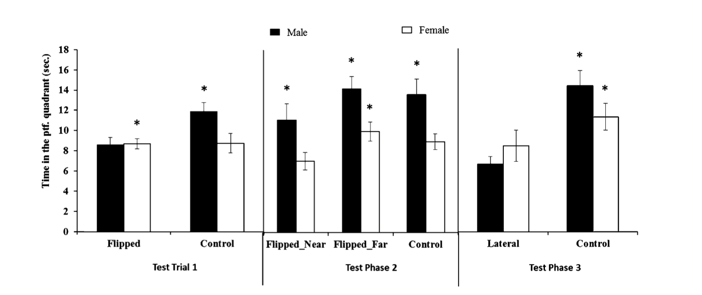

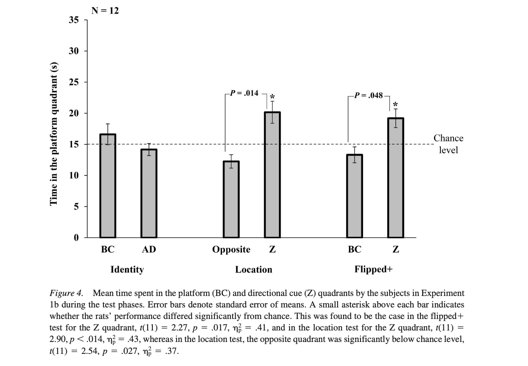

Civile, Chamizo, (2020) exp1a

best performance in normal conditions

worst performance in inverted

rats struggled when spatial arrangement is flipped

Z alone isnt sufficient

rely on Z & near (B & C)

Civile, Chamizo, (2020) exp1b

B & C alone had weak effect

contributed navigation but less affective without z

Z alone provided strong guidance

rats stayed in quadrant