Social Influence: Conformity (Week 8) Milgrim +Persuasion

1/54

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

55 Terms

Nonconscious imitation

Babies mimic simple gestures in adults from an early age. Adults also unwittingly mimic small gestures in each other all the time. . • This is sometimes known as the ‘chameleon effect’ 5 • People are particularly likely to mimic others when there is a high motivation to affiliate.

Conformity definition

• Conformity: The tendency to change our perceptions, opinions or behaviour in ways that are consistent with group norms. • Some level of conformity necessary for a cohesive society. • But can have harmful consequences when people conform to damaging behaviours.

Classic research on conformity: Sherif

Sherif (1936) • Sherif had participants focus on a spot of light on a dark wall and asked them to estimate how far the light had moved (the autokinetic effect). • When participants were tested individually, their answers varied widely from person to person. • When participants were tested as a group, their estimates quickly converged : a group norm emerged.

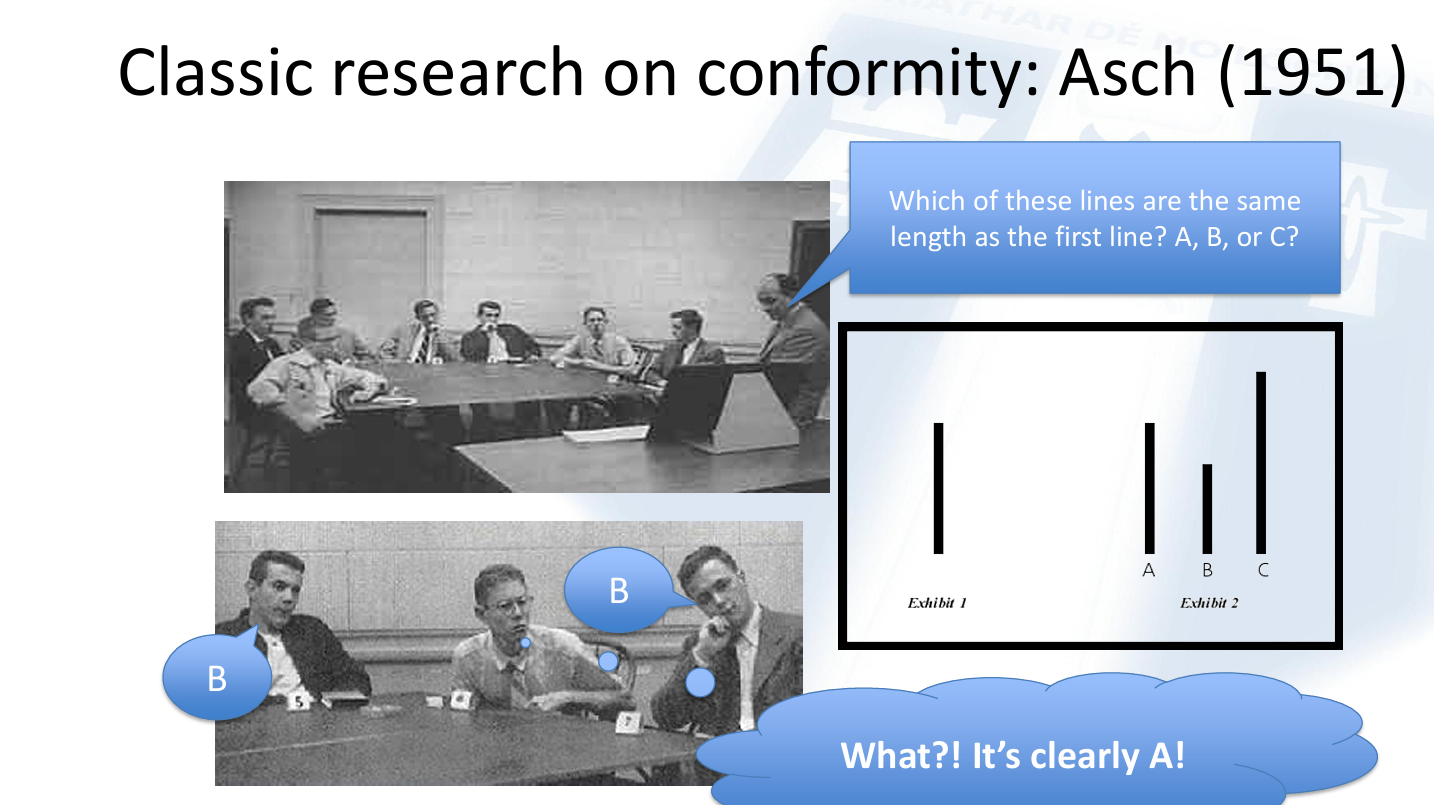

Results • Asch found that his participants went along with the incorrect majority 37% of the time. • Where participants were tested as individuals rather than in groups they made almost no errors. • 50% of participants went along with at least half of the incorrect judgments. • Only 25% of participants refused to agree with any of the incorrect group judgements.

Comparison of Study Results

• Sherif’s study – Participants turned to each other for guidance– When faced with ambiguity and uncertainty about personal judgment, • Asch’s study others can serve as a valuable source of information– Group norms, once established, are a powerful guide to later behavior.– Participants felt they were in an awkward position– People will sometimes conform, even when they are not convinced the group is right, to avoid feeling conspicuous, crazy, or like a misfit

Why do people conform?

• A need to be correct– Informational influence: Influence that produces conformity when a person believes others are correct in their judgements

• A fear of ostracism– Normative influence: Influence that produces conformity when a person fears the negative social consequences of appearing deviant.

Types of conformity

• Private conformity: The change of belief that occurs when a person privately accepts the position taken by others.

• Public conformity: A superficial change in overt behaviour without a corresponding change of opinion that is produced by real or imagined group pressure.

Majority Influence

• Group-related factors that influence feelings of pressure and insecurity that lead to conformity

– Size • Influence diminishes beyond 3 to 4 confederates

•We do more than count numbers, we try to assess the number of independent minds

– Cohesion

• The more cohesive the group is, the more power the group has over its individual members

– Perceived interdependence

• When people perceive that they need to work with other people to reach a common goal, then conformity increases.

– Social identity • We are more likely to conform to a group norm when adherence to that norm is crucial to our identity as a group member. • This can occur even in situations where other group members are not present.

Individual factors

Are some people more likely to conform than others? • Mixed evidence for personality types – those with authoritarian tendencies are more likely to conform.

• Some suggestion that people who score highly on the ‘agreeableness’ personality trait are more likely to conform.

• Men are less likely to publicly conform than conformity. women – but no consistent evidence for private – Experimental evidence suggests that this is because it is more important to men’s self-image to be seen as non-conformist.

Cultural factors

• Societies differ around the cultural value placed on conformity. • Collectivist cultures: conformity is seen as a positive factor promoting cohesion and harmony in the group, as well as a sense of interpersonal responsibility. • Individualist cultures: conformity is seen as limiting innovation and social change, as well as a constraint on individual freedom

Dissent

Having an ally in dissent • A single confederate who agrees with a dissenter can reduce conformity (in the Asch studies, by almost 80%) • Any dissent, whether it validates an individual’s opinion or not, can reduce normative pressures to conform

Conversion theory

• The power of social norms and conformity is generally on the side of the majority. • Majorities often have the power to coerce their audience to agree with them – at least outwardly. However, minorities have the advantage of their minority position making them stand out meaning they can gain attention for their 22 argument.

Processes and Outcomes of Minority Influence

• How do majorities and minorities create change?

– Majorities elicit public conformity through stressful normative pressures on the individual

– Minorities elicit private conformity by leading others to become curious and rethink their original positions

• However, even if someone has changed their mind due to a minority, they may not want to show it.

– Majority groups win compliance, but not necessarily acceptance.– Minority groups win acceptance without achieving compliance.

Minority influence & consistency

Minority arguments are most effective when dissenters are consistent: those in the minority must be forceful, persistent and unwavering in their position.

Minority influence & consistency: two components

• Diachronic consistency: Individuals in the minority group should show stability over time.

• Synchronic consistency: Individuals in the minority position should demonstrate stability across the group. • I.E. If minority members change their minds or disagree with each other, they lose their clear distinctive position and are likely to have any contradictions in their argument noticed. – However, if minorities remain consistent, the audience attempts to understand why they consistently hold this position, and engages with their argument.– Ironically, this requires strong message discipline and conformity within the minority group.

Majority and Minority Social Influences

• Depends on type of judgment– Majorities have greater impact on factual questions; minorities exert equal impact on opinion questions (Maass et al, 1996).

• Also depends on how and when measured– Majorities have more influence when measured directly, publicly, or immediately– Minorities exert a strong influence when measured indirectly or privately, when attitude issues are related but not focal to point of conflict, or after passage of time. • Minorities are more likely to be successful if they can represent themselves as a minority within the in-group. If their minority argument leads to the audience seeing them as ‘outsiders’, they are less likely to be successful.– Therefore, minorities will be more successful if they can appeal to shared values and experiences with the audience and the majority group

Persuasion and compliance

Changes in behaviour that are elicited by direct requests/orders. How do we get people to do what we want them to, that they would not have done otherwise?

3 elements of persuasion

• The source– Who is doing the persuading?

• The message– How are they trying to get people to comply?

• The target– Who is receiving the message?

Known as the “Yale approach to communication and persuasion”. Originally developed by Carl Hovland in designing propaganda for the US War Department during WWII. Later adapted for widespread use in marketing.

The source

• People who are perceived as attractive, likeable and similar to the target tend to have greater persuasive success. • We also tend to find those who have high levels of perceived credibility, expertise and trustworthiness more persuasive. There’s a reason toothpaste ads tend to use good-looking dentists!

The message

• Messages that are consistent with the target’s prior beliefs and attitudes are more likely to be persuasive. • Messages are more effective if they are repeated regularly however some level of variation is necessary to prevent attention loss. • Messages that induce fear are more memorable – but they people or change behaviour. need to present a problem as solvable in order to persuade • The most persuasive messages seem to contain a combination of appealing to people’s sense of reason (factual advertising) and their subjective opinions and emotions (evaluative advertising)

The audience

Evidence that teenagers and young adults are most susceptible to persuasion – we become less so in middle adulthood, but slightly more susceptible again in late adulthood. People who have a higher need for cognition (NFC) i.e. who derive fulfilment from thinking things through – are less easily persuadable. People who are in a good mood tend to be more compliant.

Theory of the week: The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion

• Petty & Cacioppo (1986) • Argues that people will either adopt a central or peripheral route to persuasion depending on their ability or motivation to carefully think about the message.

The central route

• When we think carefully about a persuasive message and pay special attention to the argument quality. • Central cues of a message may include:– Scientific information– Consumer reports– Expert arguments • Takes significant effort to process -depends on ability and motivation

The peripheral route

• When we attend more to the superficial characteristics of the message instead of the argument quality.– Alternatively, we may pay more attention to the source than the message itself. • Peripheral cues of a message may include:– Well-designed Graphics– Attractive/likeable models– Memorable slogans– Attention-grabbing music/jingles • These cues do not take a great deal of 9 cognitive effort or motivation to process.

What factors determine what route we take?

• Ability to focus– When we are distracted, preoccupied or under time pressure, we are more likely to attend to peripheral cues.

• Motivation to process– If we are not that interested in engaging with the message, we are more likely to rely on peripheral cues such as message length.

– Motivation can be affected by NFC, which makes attending to central cues more likely.– If the message is about something personally important to us, we are more likely to employ the central route, so long as we have the time and resources necessary to pay attention.

What route is more effective?

• Engaging the peripheral route may be more successful in making low-impact decisions or purchases, or in causing superficial or temporary attitude change. • Engaging the central route tends to be more effective for high-impact decisions or purchases, or in causing longer-lasting attitudinal or behavioural change.

Persuasion tactics

• Various two-step techniques of presenting a request that makes compliance more likely.

• Many of these are derived from the work of Robert Cialdini, a social psychologist whose work on persuasion and influence has had a major impact on sales and marketing methods.

The norm of reciprocity

• Strohmetz et al (2002) Including sweets/a smiley face with a bill increases the likelihood of a tip. • Regan (1971) ‘Coke study’: We feel compelled to return an unsolicited favour even if the person isn’t otherwise likeable. • However, time-limited: Burger (1997) found compliance levels were much lower after a week had passed.

Freedman & Fraser (1966)

1. Experimenter, posing as consumer researcher telephoned housewives in California and asked them would they be willing to answer questions about the household products they use. 2. Three days later, experimenter called back and asked permission to visit houses and take an inventory of their household goods. • Where participants were confronted with both requests, 53% consented. • Where participants were only confronted with the second request, only 22% 14 consented

Foot-in-the-door

• Where you set the stage for the real request by first getting someone to comply with a much smaller request. • Self-perception theory explanation:

1. By agreeing to the initial request, you see yourself as a helpful person.

2. When confronted with the bigger request, you seek to act in a way that maintains this self-image.

Lowballing

Two-step compliance technique in which the influencer secures agreement with a request but then increases the size of the request by revealing hidden costs Psychology of commitment:

• Once you make a particular decision, you justify it to yourself, and avoid cognitive dissonance, by thinking of all its positive aspects. • You may also want to avoid being seen to go back on your word.

• Lowballing is more successful as a technique when the initial agreement is made in public.

Door-in-the-face technique

• Where you set the stage for the real request by first making an outrageously large request that you know will be rejected.

• Perceptual contrast: The second request seems smaller in contrast to the first than it would do in isolaton.

• Reciprocal concessions: We view the move from a large request to a smaller one as a concession that we should match

‘And that’s not all!’

• Where you make an inflated request, then decrease its apparent size by offering a discount or bonus. • Burger (1986):– “These cupcakes are 75c!”: 44% purchase rate.– “These cupcakes are $1 – no wait, let’s make it 75c!”: 73% purchase rate

Framing

• Decisions are affected by whether their outcomes are presented as gains or avoided losses. • Describing a foodstuff as 95% fat free persuades more customers than describing it as 5% fat. • People are more likely to enroll for a course described as having an ‘early-bird discount’ rather than a ‘late registration penalty’.

Request justification

• A request that sounds justified is often complied with even when the justification is meaningless. • We sometimes process small oral requests lazily, without critical thought. Langer et al (1978)

• “Excuse me. I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine?”: 60% compliance • “Excuse me. I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine because I’m in a rush?”: 94% compliance • “Excuse me. I have five pages. May I use the Xerox machine because I need to make some copies?”: 93% compliance

Compliance in Conversation

• Conversation Analysis: The in-depth study of the psychological effects of talk. • CA study of services calls demonstrate what sentence constructions are more likely to get people to comply. • In particular, sentences that position someone as a reasonable person seem to be effective– e.g. “yeah, but you’d be willing to try it, right?

When persuasion doesn’t work?

• Reactance: When the persuader pushes too hard, and provokes a negative reaction.– This can sometimes be a problem with ‘fear appeals’ in health messaging.

• Forewarning: When you know that someone is about to try and persuade you of something, that gives you time to think up counterarguments.

• Avoidance: Simply not engaging (e.g. skipping through the ads).– But we are less likely to avoid a message that seems to be consistent with our pre-existing attitudes.

Obedience

Behaviour change produced by the commands of authority

The Nuremberg Defence

Thousands of those accused of war crimes following WWII excused their behaviour with the phrase “Befehl ist Befehl”: Orders are Orders.

Question for social psychologists: Will people really carry out atrocities because they’re told to by an authority figure?

According to Milgram’s Obedience Experiments… …the answer appears to be ‘yes’

Social Impact Theory • Bibb Latané (1981)

The Psychology of Social Impact. • Argued that social forces act on individuals the same way physical forces act upon objects. • Social influence depends on the strength, immediacy and number of source persons relative to target persons. 26

Strength

• The strength of a source is determined by his/her status, ability or relationship to a target.

• The stronger the source, the greater the influence.

• We are more likely to conform to the behaviour of other group members we view as competent.

Sources enhance their strength by making targets feel obligated to comply e.g. by returning a small favour.

• Authority figures gain strength by wearing uniforms, thus making obedience more likely

Immediacy

• A source’s proximity in time and space to the target.

• The closers others are, the more impact they have on us: we are more likely to conform to their behaviour.

• Obedience levels increase when the authority figure is physically present.

Number

• As the number of sources increases, so does their influence • Or at least, up to a point –remember Asch found a levelling off beyond 4

Social Impact Theory & resistance

Total influence may be diffused by the strength, distance and number of target persons. • There will be less impact on a target who is strong and far from the source than on a target who is weak and close to the source. • There will be less impact on a target who is accompanied by other target persons.

Recap

• We will often consciously or unconsciously, alter our behaviour to fit in with others.

• Conformity can be private or public, either because we don’t want to be wrong, or we don’t want to be ostracised. substance when less thought is involved.

• Persuasion can be achieved either through a central route or a peripheral route, with style being more important than

• Compliance can be increased through various two-step techniques to make a request seem more reasonable than it is.

• The presence of an authority figure increases obedience.

• Social influence is mediated by strength, immediacy and number of sources.

The banality of evil

• The 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann led Hannah Arendt to coin the phrase ‘the banality of evil’. – Eichmann and others were moved less by great hatreds, than by the petty desire to do a task well and please their superiors. • During his trial, Eichmann was examined by six psychologists. None found him to have in any way an abnormal personality. • Social psychologists became interested in the dynamics through which ‘ordinary people’ willingly carry out atrocities at the behest of authoritarian regimes.

Stanley Milgram

(1933-1984) Before he was famous… • Parents Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe.

• First degree in Political Science (Minor in Arts).

• Took a PhD at Harvard supervised by Gordon Allport.

• Before completing his PhD worked at Princeton as a research assistant for Solomon Asch.

1960: Milgram appointed to his first (untenured) lecturing post at Yale. • Decides to research a problem “of great consequence”. I know – I’ll outdo Asch!

• Milgram argued that the task in Asch’s studies (line measurement) was too trivial to be a valid measure of conformity.

• He wondered “whether groups could pressure a person into performing an act whose human import was readily apparent” e.g. harming another person.

Milgram’s ‘incandescent moment’

What if there was no group present, but only instructions from an experimenter? Just how far would a person go under the experimenter’s orders?

The basic premise of the Milgrams experiment

• Participants were told that they were taking part in an experiment designed to test the effect of punishment on learning.

• They were ‘randomly’ assigned to the role of ‘teacher’, while another participant (actually an actor) was assigned to the role of ‘learner’.

• The ‘teacher’ was told by the experimenter to administer electric shocks of increasing voltage to the ‘learner’. • Questions: Would the participant comply? How far would they go? In actuality, no shocks were administered at all. The machine was fake and the ‘learner’ was an actor. But the participant didn’t know that…

The shock generator→ Designed to look intimidating!

The “Experimenter” Jack Williams Cast to be ‘stern and intellectual’

Mr Wallace (The “learner”) Cast to be ‘mild and submissive and not at all academic’.

James McDonough Recruitment Diverse volunteer sample (approx. 1000) • 40% blue-collar workers • 40% white-collar workers • 20% professionals

Procedure • When the participant arrived at the lab, they were greeted by the ‘experimenter’ and the other ‘participant’. • The ‘experimenter’ explained the nature of the experiment and drew lots to decide who would be the ‘teacher’ and the ‘learner’.

• The teacher and learner were then taken into another room, where the learner was strapped into a chair and ‘electrodes’ were attached to his body. “Although the shocks can be extremely painful, they cause no permanent tissue damage”

Procedure • The learning task involved word pairs, where the learner had to remember which words from an original list were paired together.

• Every time the learner got an answer wrong, the teacher administered an electric shock. • The experimenter told the teacher to increase the voltage every time the learner gave a wrong answer.

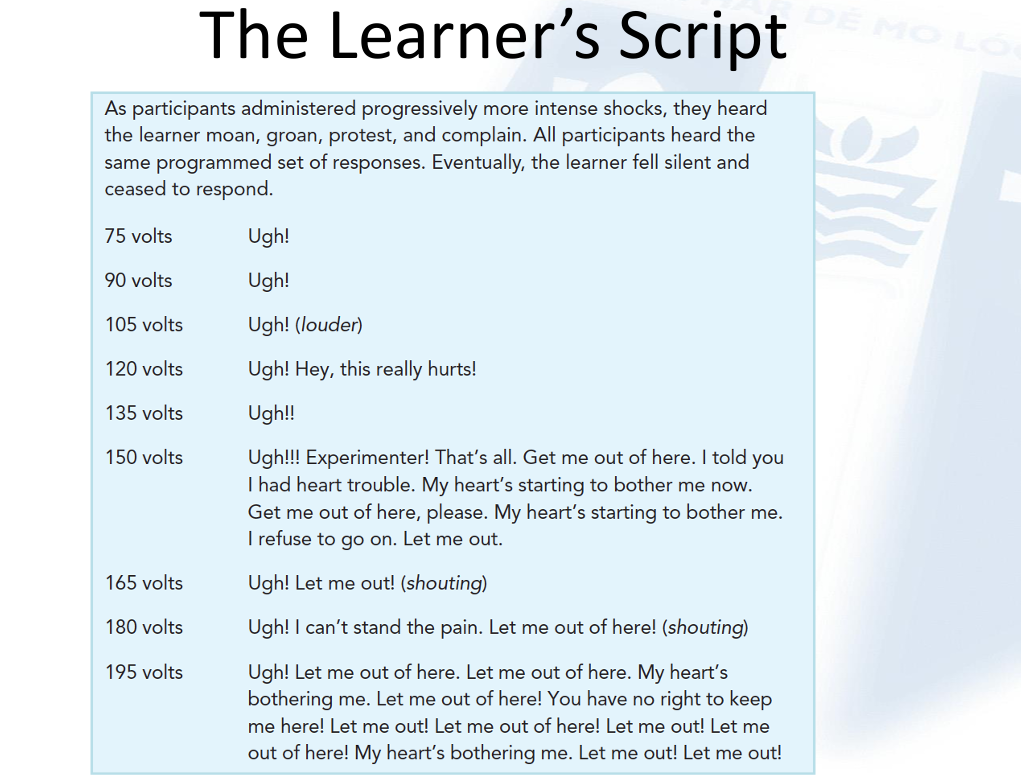

learners script

Prods Used + Results

• Experimenter’s responses to participants’ expressions of concern or reluctance to continue– “Please continue (or, please go on)”– “The experiment requires that you continue”– “It is absolutely essential that you continue”– “You have no other choice; you must go on”

Response Prediction • Do you think you would have stopped? • If so, at what point? • If not, why not? • What percentage of others do you think would have refused to administer the maximum 450 volts?

Milgram’s Results Showed an Alarming Degree of Obedience • In the initial study of 40 men from New Haven area • 100% subjects went as far as 120V (first expression of pain) • 75% went up to 300V (point of screams and refusal) • 65% went all the way, up to 450V !!! • There was no gender difference in the results when women rather than men were used.

Variants (Proximity, Authority & Multiple teachers

Variants: proximity • When the learner was in a separate room, and could not be heard except for banging on the wall, 65% went all the way to the end.– Of those who stopped, most did at 300v when banging could be heard. • When the learner was in the same room as the teacher, 40% went all the way to the end. • When the teacher had to physically press the learner’s hand to a metal plate to shock him, 30% went all the way to then end. • In these conditions, of those who stopped, more did at 150v than any other point.

Variants: authority • When the experimenter called a halt at 150v, but the learner expressed a willingness to continue, all participants stopped. • When the experimenter was an ordinary man, not a scientist in a labcoat, only 20% continued to the end. • When there were two experimenters who argued with each other, 90% stopped at the 150v mark.

Variants: multiple teachers • When the participant was accompanied by two other ‘teachers’, one of whom refused to continue at 150v, and the other at 210v, only 10% continued to the end. • When the participant only had to assist the other teacher, who actually administered the shocks, 92.5% continued to the end.

Important Factors in Milgram’s Results

• Elements of the procedure– Participants were led to feel relieved of personal responsibility for the victim’s welfare

– Gradual escalation in small increments was used

– The situation was novel, with unknown norms

– The task was quickly paced, preventing participants from considering their values and options, thinking about possible consequences, or making careful decisions

So … However.. Debrief the results

So… 1. Milgram’s studies demonstrate disobedience as well as obedience. The critical question has as much to do with when people obey as why they do.

2. Participants don’t obey just anyone – their obedience is contingent upon a legitimate authority providing clear guidelines.

3. People are highly responsive to other voices in the study.

However… Experimenter’s responses to participants’ expressions of concern or reluctance to continue– “Please continue (or, please go on)”– “The experiment requires that you continue”– “It is absolutely essential that you continue”– “You have no other choice; you must go on”

• Evidence from tapes and archives is that the experimenter often went beyond these prods, engaging in an ongoing argument with ‘teachers’ • Does this blur the line between ‘obedient’ and ‘defiant’ participants?

• Direct orders from authority were in fact less effective than argumentation, persuasion and negotiation. (Gibson, 2015).

Theorising the results • Milgram argued that his participants had entered an ‘agentic state’ – shifting from acting in terms of their own purposes to acting as an agent for someone else’s. • Haslam & Reicher argue for engaged followership – participants shocked the learner because they identified with the scientific enterprise and wanted to help the experimenter and make a contribution.

Milgram’s ethics & the debate about it

I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse. He constantly pulled on his earlobe, and twisted his hands. At one point he pushed his fist into his forehead and muttered: "Oh God, let's stop it." And yet he continued to respond to every word of the experimenter, and obeyed to the end [Milgram, 1963, p. 377].

The debate about research ethics. • Should Milgram’s research be judged by the standards of his time? • Do the ends justify the means? (When should a scientist’s responsibility to uncover the truth, trump concerns over the rights of research participants?) • Is the “ethical” status of research solely a matter of the way in which we treat the research respondents?

‘De-hoaxing

’ • Milgram did conduct a debriefing session immediately after the experiment where (some) participants were told the true nature of the experiment – and met the fit and healthy actor playing the ‘victim’! • They were reassured about their behaviour during the experiment and that it didn’t mean they were a bad person. • Later, they also received a full written report about the studies and a follow-up questionnaire that assessed their thoughts and feeling about participating.