Microbe Mission

1/256

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

257 Terms

Microscopy

..

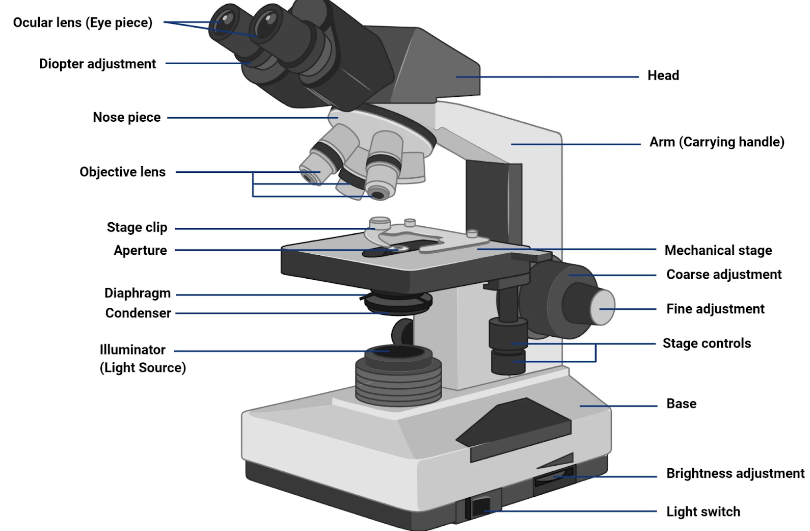

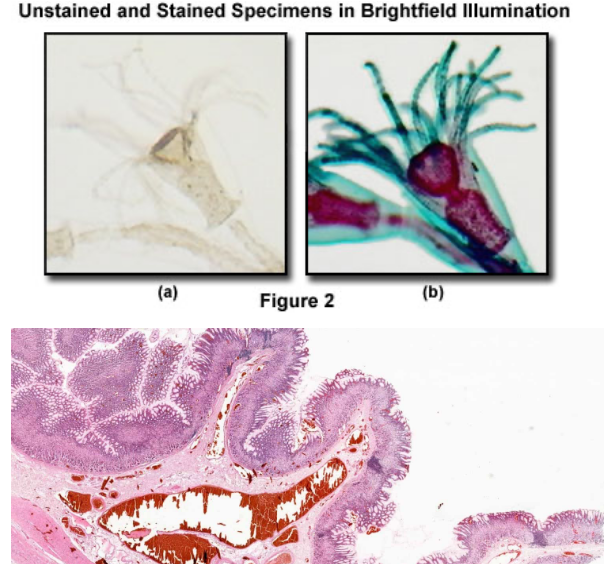

Compound Light Microscope (Brightfield Microscopy)

Simplest Optical Microscopy

Common

Uses a set of glass lenses to focus light rays passing through a specimen to produce and image that is viewed by the human eye

Dark image against a light background

Compound Light Microscope contd.

Specimens must be stained and put in a beam of illuminating light

Provides color contrasting characterization

Produces high resolution image through focus

Viewed under oil immersion on a microscopic slide

Could be used to observe cell growth

Compound Light Microscopy in practice

Best for:

Observing stained or unstained specimens at the cellular level with moderate magnification (up to ~1000x).

Ex. Identifying cell shape differences in various bacterial strains.

Why?

A compound microscope provides a quick and easy way to visualize cells and basic structures.

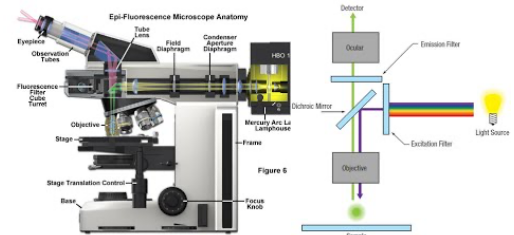

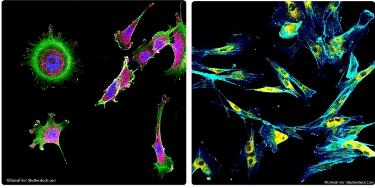

Fluorescence Microscopy

Uses fluorescence to study organic and inorganic substances

Specimen is illuminated in blue or UV light (short wavelength) transmitting fluorescence against a dark background

Luminosity on a dark background through fluorescense on specimen

Fluorescence Microscopy in practice

Best for:

Visualizing specific proteins, organelles, or molecules in living or fixed cells using fluorescent labels.

Ex. Tracking the movement of a specific protein within a live cell.

Why?

Fluorescence microscopy allows for specific labeling using fluorophores and enables live-cell imaging.

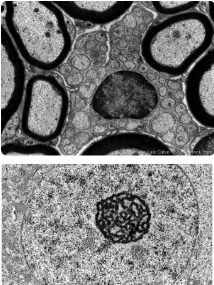

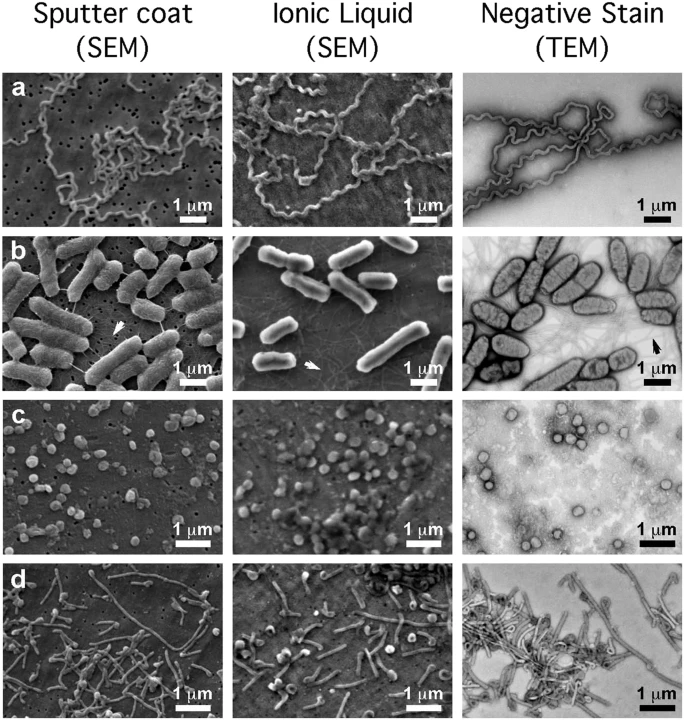

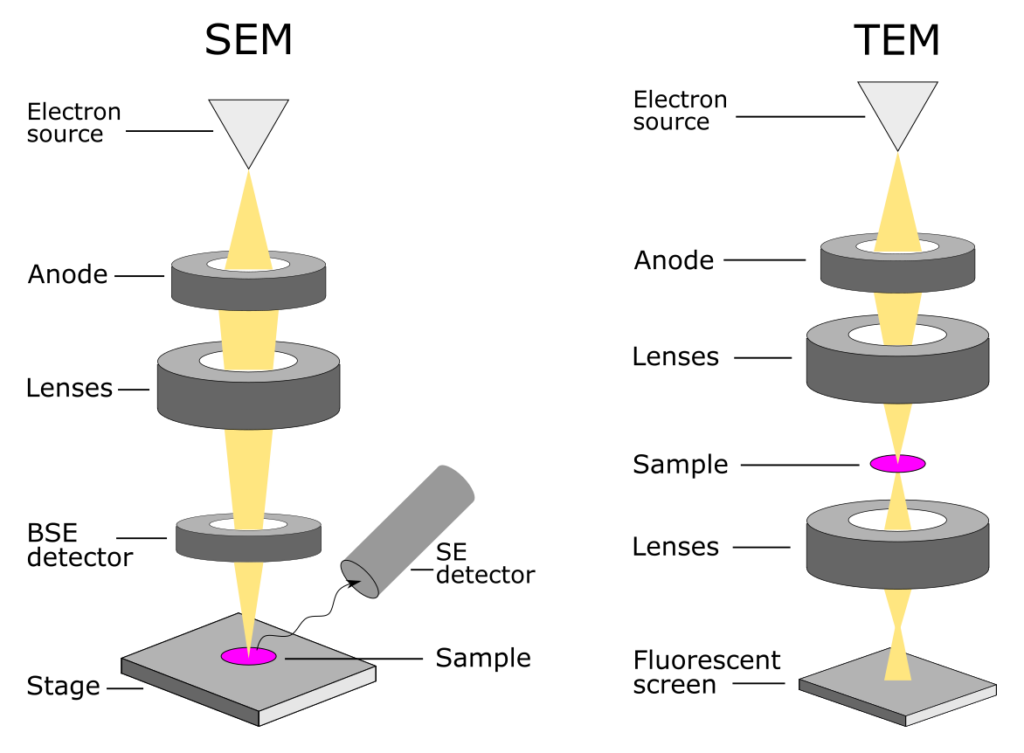

Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

Uses a set of electromagnetic lenses to focus a beam of electrons passing through a specimen to produce an image

Views molecules, tissues, cells, where electrons may pass

Projecting image on fluorescent screen or film

TEM in practice

Best for

observing the internal ultrastructure of cells, organelles , and biomolecules at very high resolution (nm)

Ex. determining the presence of specific organelle structures in a diseased cell

Why?

provides extremely high magnification and resolution, allowing detailed visualization of cellular interiors

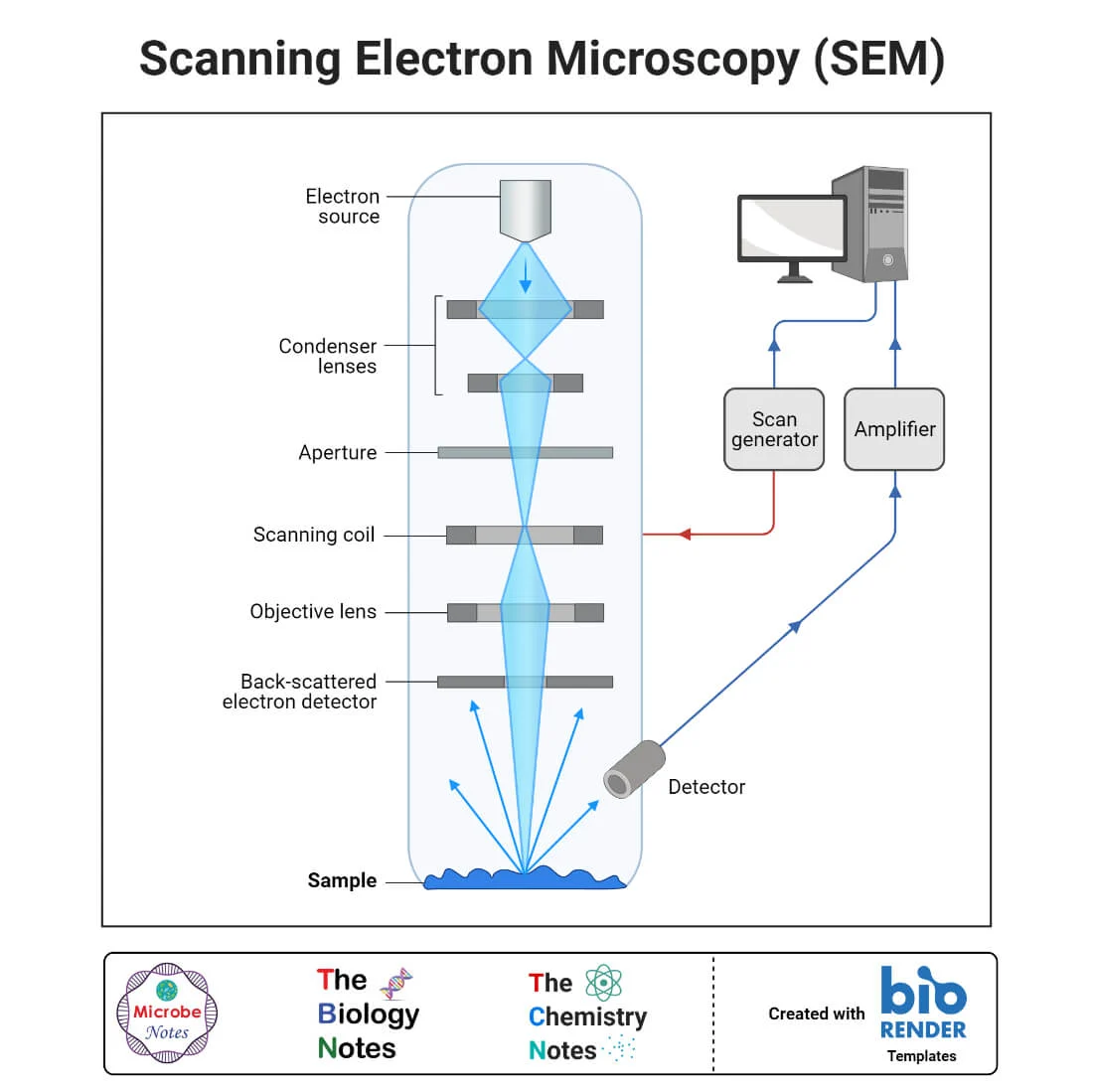

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Uses a narrow beam of electrons to scan over the surface of a specimen that is coated with a thin metal layer.

Secondary electrons given off by the metal are detected and used to produce a 3D image on a tv screen

Detects reflection electrons

SEM in practice

Best for

observing the internal ultrastructure of cells, organelles , and biomolecules at very high resolution (nm)

Ex. studying the texture and surface features of bacterial bio films

Why?

provides detailed surface imaging with high depth of field

Differences in Magnification in Electron vs Compound Microscopes

Ratio from image to actual size

Electron microscopes magnify more than compound

Difference in electron and light wavelengths magnifies ability to distinguish between two points

Differences in Resolution in Electron vs Compound Microscopes

Differentiating between two objects (to be able to seen as two separate objects

Better resolution = better detail

Heightened by placement of oil between sample and objective lens, and use of UV lights

Differences in Contrast in Electron vs Compound Microscopes

Difference in shading compared to background

Higher contrasts —> staining with dyes or electron dense metals; phase/differential interference contrast; or using fluorescently tagged antibiotics

Structure and Morphology

…

Structure of Prions

Misfolded proteins that lack DNA or RNA

Composition of Prions

Primarily composed of the misfolded prion protein (PrP), which can induce normal proteins to misfold.

Function of Prions

Cause neurodegenerative diseases (ex. mad cow disease) by creating spongy holes in the brain (TSE) and disrupting normal cellular functions.

Starts a chain reaction that converts more proteins

Structure of Viruses

Genetic material inner core (DNA or RNA, single- or double-stranded).

Protein coat (capsid) that protects the genetic material.

Some have a lipid envelope (derived from the host membrane) for additional protection.

Composition of Viruses

Nucleic acids (DNA or RNA).

Proteins (capsid proteins, enzymes for replication).

Lipids (if enveloped).

Viral Enzymes assist in the replication and asembly of new viral proteins (ex. reverse transcriptase, RNA polymerase)

Tail Fibers in bacteriophages help attach to and inject genetic material into host bacteria

Matrix Proteins in some enveloped viruses provide structural support beneath the envelope and help in the assembly of new viral particles (ex. in HIV)

Function of Viruses

Function:

Obligate intracellular parasites that hijack host cell machinery to replicate.

Some integrate their genome into the host (e.g., HIV, herpesviruses).

Host specific

Structure of Bacteria

Prokaryotic, unicellular.

Cell wall (made of peptidoglycan in most species).

Plasma membrane, ribosomes, nucleoid (circular DNA, no nucleus).

Some have flagella, pili, or capsules.

Composition of Bacteria

DNA (circular chromosome + sometimes plasmids).

Proteins (enzymes, ribosomal proteins).

Lipids (membranes).

Peptidoglycan (cell wall in most species).

Plasma Membrane

Glycocalyx (capsule/slime layer of carbohydrates in some species)

Function of Bacteria

Play essential roles in ecosystems

Ex. decomposers, nitrogen fixation, gut microbiota

Some can be pathogenic (e.g., Streptococcus, E. coli).

Structure of Archaea

Prokaryotic, unicellular.

No peptidoglycan in the cell wall (unlike bacteria).

Unique membrane lipids (ether-linked rather than ester-linked).

Composition of Archaea

DNA (circular genome, similar to bacteria).

rRNA similar to eukaryotes

introns and histone proteins

Proteins & ribosomes (more similar to eukaryotes than bacteria).

Lipids (branched, ether-linked membrane lipids).

Function of Archaea

Often live in extreme environments (e.g., thermophiles in hot springs, methanogens in anaerobic conditions).

Some play roles in carbon and nitrogen cycling.

Ex. methanogens, halophiles, thermoacidophiles, moderate environment

Structure of Eukaryotic Microbes

Eukaryotic, unicellular or multicellular.

Nucleus, membrane-bound organelles (mitochondria, Golgi, ER).

Some have cell walls (e.g., fungi = chitin, algae = cellulose).

Can have cilia, flagella, pseudopodia for movement.

Lysosomes, chloroplasts, mitochondria, cytoskeleton, peroxisomes

Composition of Eukaryotic Microbes

DNA (linear chromosomes in nucleus).

Proteins (enzymes, structural proteins, etc.).

Lipids (plasma membrane, organelle membranes).

Polysaccharides (cell wall in some).

Function of Eukaryotic Microbes

Some are free-living (e.g., Amoeba, Paramecium), while others are pathogens (Plasmodium causes malaria, Candida is a fungal pathogen).

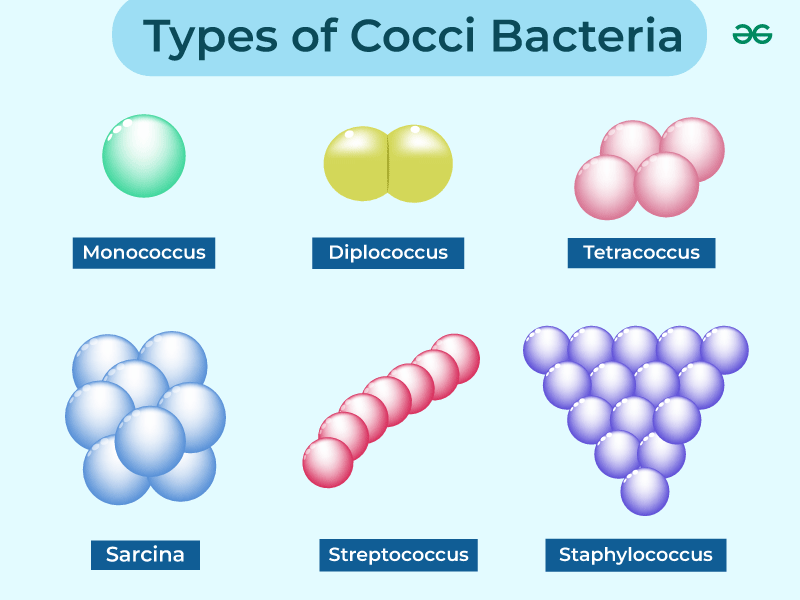

Bacteria Shape: Coccus

Spherical

Description: Round or oval-shaped bacteria.

Examples:

Streptococcus (forms chains)

Staphylococcus (forms clusters)

Neisseria (diplococci, pairs)

Arrangement Types:

Diplococci (pairs)

Streptococci (chains)

Staphylococci (clusters)

Tetrads (groups of four)

Sarcina (cube-like structures)

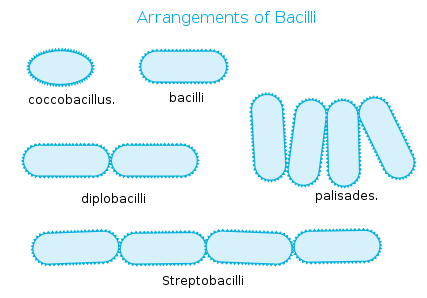

Bacteria Shape: Bacillus

Rod-Shaped

Description: Cylindrical, elongated bacteria.

Examples:

Escherichia coli (E. coli)

Bacillus subtilis

Salmonella

Arrangement Types:

Single bacillus (individual rods)

Diplobacilli (pairs)

Streptobacilli (chains)

Coccobacillus (short, oval-like rods)

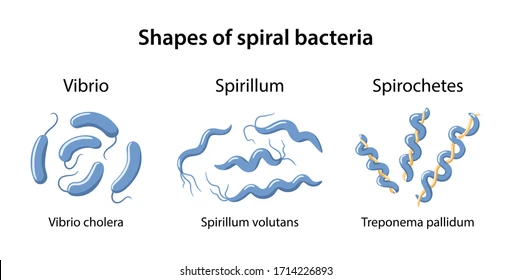

Bacteria Shape: Spirilli

Spiral-Shaped

Description: Curved or twisted bacteria.

Types:

Vibrio (comma-shaped) → Vibrio cholerae

Spirillum (rigid, wavy) → Spirillum volutans

Spirochete (flexible, corkscrew-shaped) → Treponema pallidum (causes syphilis)

Bacteria Shape: Etc.

Filamentous Bacteria: Long thread-like chains (e.g., Streptomyces).

Pleomorphic Bacteria: Can change shape depending on the environment (e.g., Mycoplasma, which lacks a cell wall).

Appendaged Bacteria: Bacteria with extensions such as stalks or prosthecae. (ex. Caulobacter crescentus)

Appendages help in attachment to surfaces and nutrient absorption.

Box-Shaped (Square) Bacteria: Flat, square-shaped bacteria found in extreme environments like saltwater. (ex. Haloquadratum walsbyi)

The square shape maximizes surface area for efficient nutrient exchange.

Star-Shaped Bacteria: Bacteria with star-like projections. (ex.Stella species)

Likely helps in increased surface area for nutrient absorption and adhesion.

Triangular Bacteria: Bacteria with a triangular shape, rare in nature. (ex. Haloarcula archaea species: sometimes classified among bacteria).

Adaptation to extreme environments like high-salt condition

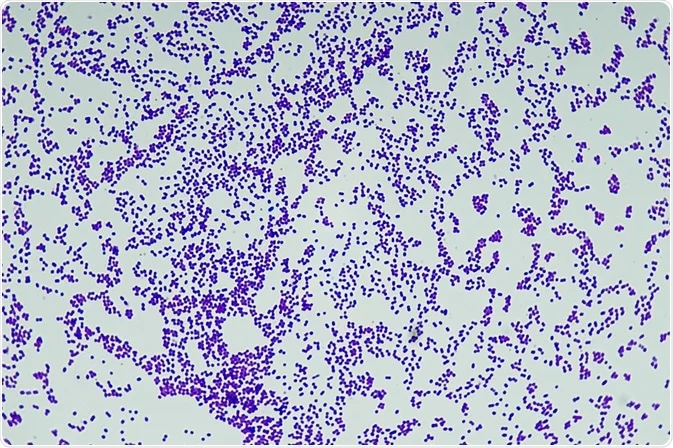

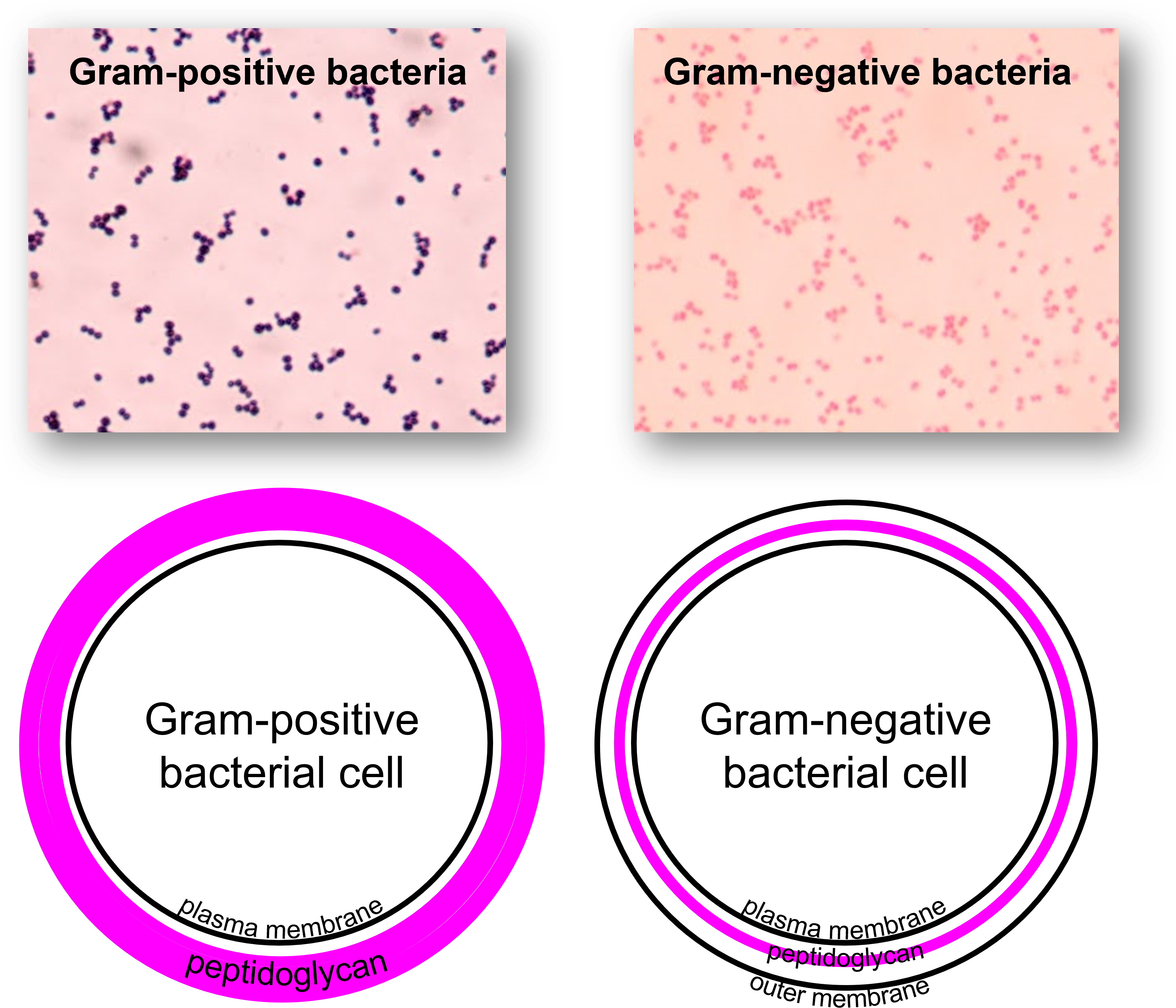

Gram Positive (+) Bacteria

Cell Wall: Thick peptidoglycan layer

Outer Membrane: Absent

Gram Stain Color: Purple (retains crystal violet)

Teichoic Acids: Present

Lipid Content: Low

Periplasmic Space: Absent or small

Endotoxin (LPS): Absent

Resistance to Antibiotics: More susceptible (e.g., penicillin, lysozyme)

Ex: Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Bacillus

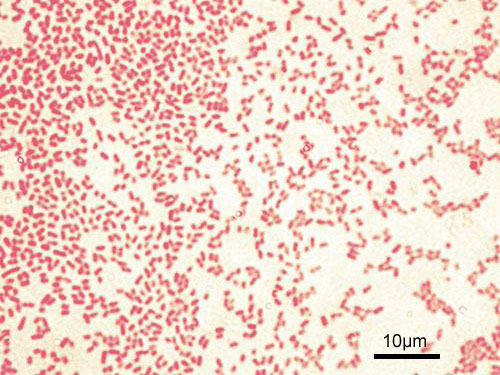

Gram Negative (-) Bacteria

Cell Wall: Thin peptidoglycan layer

Outer Membrane: Present (contains lipopolysaccharides - LPS)

Gram Stain Color: Pink/Red (loses crystal violet, retains safranin)

Teichoic Acids: Absent

Lipid Content: High (due to outer membrane)

Periplasmic Space: Large

Endotoxin (LPS): Present (lipopolysaccharide in outer membrane)

Resistance to Antibiotics: More resistant (outer membrane acts as a barrier)

Ex: Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella

Gram positive vs negative stain side by side

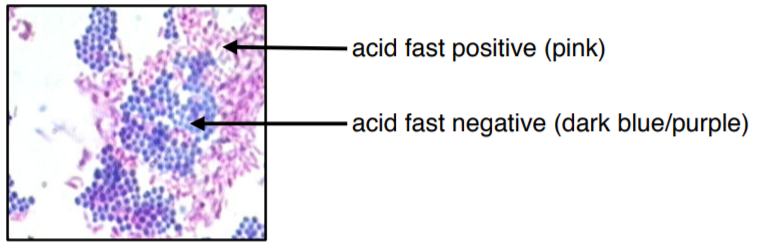

Acid-Fast Cells

Cell Wall: Thick peptidoglycan layer covered with mycolic acids (waxy lipid layer)

Outer Membrane: Absent, but has a waxy lipid layer that provides protection

Staining:

Does not stain well with Gram stain

Requires Ziehl-Neelsen stain (stains red with carbol fuchsin)

Peptidoglycan Layer: Thick but shielded by mycolic acids

Teichoic Acids: Absent

Lipid Content: Very high (due to mycolic acids)

Periplasmic Space: Present

Endotoxin (LPS - Lipopolysaccharide): Absent

Antibiotic Resistance:

Highly resistant due to waxy cell wall

Resistant to many antibiotics, disinfectants, and immune defenses

Example Bacteria: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium leprae

Gram Stain Procedure

Laboratory technique used to differentiate bacterial species into two groups based on the characteristics of their cell walls.

Helps identify and classify bacteria, guiding treatment decisions (ex. choosing correct antibiotics)

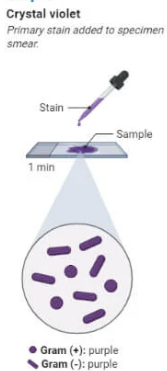

Gram Staining Procedure Step 1

Prepare the Slide

Smear a small amount of bacterial sample onto a microscope slide.

Air-dry the smear, then heat-fix it by gently passing the slide through a flame to kill the bacteria and make them adhere to the slide.

Gram Staining Procedure Step 2

Primary Staining (Crystal Violet)

Flood the slide with crystal violet dye for 1 minute.

Crystal violet stains all bacterial cells purple.

Rinse the slide gently with water.

Gram Stain Procedure Step 3

Mordant (Iodine Solution)

Add iodine solution (Gram’s iodine) for 1 minute.

The iodine forms a complex with the crystal violet, helping the dye bind more tightly to the peptidoglycan layer.

Rinse the slide gently with water.

Gram Staining Procedure Step 4

Decolorization (Alcohol or Acetone)

Add alcohol or acetone (decolorizer) drop by drop, until the runoff is clear.

This step differentiates the bacteria:

Gram-positive bacteria retain the crystal violet-iodine complex and stay purple.

Gram Staining Procedure Step 5

Counterstaining (Safranin)

Flood the slide with safranin stain for 1 minute.

Safranin stains the Gram-negative bacteria red or pink.

Rinse the slide gently with water.

Gram Staining Procedure Step 6

Dry the Slide

Gently blot the slide dry with bibulous paper or allow it to air dry.

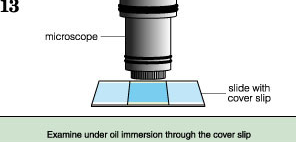

Gram Staining Procedure Step 7

Observation

Examine the slide under a microscope, starting with a low-power objective and moving to high power.

Gram-positive bacteria will appear purple (due to the crystal violet), while Gram-negative bacteria will appear pink/red (due to the safranin).

Culture and Bacteria

…

Solid Media (Agar-Based Cultures)

Used to grow, isolate, and study bacterial colonies.

Widely used in microbiology for idenitification, antiobiotic sensitivty testing, and research

Consist of a nutrient-rich medium solidified with agar

Agar: a gelatinous substance that provides a stable surface for bacterial growth.

Key Features of Solid Media (Agar-Based Cultures)

Solid Surface: Allows for the formation of visible bacterial colonies.

Isolation of Bacteria: Helps separate individual bacterial species from mixed cultures.

Control Over Growth Patterns: Supports selective and differential growth for identification.

Reproducibility: Provides consistent results for microbial studies.

Solid Media: Streak Plate Method

Used to isolate single colonies from a mixed culture.

Bacteria are spread across an agar plate using an inoculating loop.

Solid Media: Spread Plate Method

Bacteria are evenly spread over the agar surface using a sterile spreader.

Useful for counting colony-forming units (CFUs).

Solid Media: Pour Plate Method

Bacteria are mixed with liquid agar and poured into a petri dish.

Colonies grow within and on the surface of the agar.

Solid Media: Selective Media

Contains specific nutrients or inhibitors to promote the growth of certain bacteria while suppressing others.

Example: MacConkey agar (for Gram-negative bacteria).

Solid Media: Differential Media

Allows differentiation of bacteria based on biochemical characteristics.

Example: Blood agar (distinguishes hemolytic bacteria).

Applications of Solid Media (Agar-Based) Cultures

Isolation of Pure Colonies: Used to separate and identify individual bacterial species from mixed samples.

Colony Morphology Study: Helps observe bacterial shape, size, color, and texture.

Selective and Differential Testing: Enables differentiation between bacterial species based on biochemical properties.

Antibiotic Sensitivity Testing: Determines bacterial resistance or susceptibility to antibiotics.

Liquid (Broth) Cultures

Used to grow bacteria in a nutrient-rich liquid medium without a solidifying agent like agar.

Commonly used in microbiology for studying bacterial growth, biochemical testing, and maintaining bacterial strains.

Key Features of Liquid (Broth) Cultures

Promotes Rapid Growth: Allows bacteria to multiply quickly and evenly throughout the medium.

Used for Large-Scale Cultures: Ideal for producing high volumes of bacteria for experiments.

Uniform Distribution: Bacteria grow suspended in the liquid rather than forming colonies.

Can Support Different Oxygen Needs: Bacteria settle at different levels depending on their oxygen requirements.

Liquid Culture: Nutrient Broth Culture

Bacteria grow in a liquid medium, leading to uniform turbidity.

Used for growing large volumes of bacteria.

Liquid Culture: Enrichment Culture

Encourages the growth of specific bacteria by providing selective nutrients.

Example: Selenite broth (for Salmonella isolation).

Applications of Liquid (Broth) Cultures

Rapid and High-Density Growth: Used when large bacterial quantities are needed for experiments or industrial applications.

Biochemical and Metabolic Studies: Allows observation of bacterial growth phases and metabolic activity.

Continuous Culture Systems: Maintains bacterial populations over time, useful for research and fermentation processes.

Maintaining Bacterial Stocks: Keeps bacteria alive for extended periods without the need for subculturing.

Anaerobic Culture Methods

Techniques used to grow bacteria that thrive in low or no oxygen environments.

Create conditions that either remove oxygen or prevent its entry

Support the growth of obligate anaerobes (which cannot survive in oxygen) and facultative anaerobes (which can grow with or without oxygen).

Key Features of Anaerobic Culture Methods

Oxygen-Free Environment: Prevents oxygen exposure, which can be toxic to certain bacteria.

Controlled Atmosphere: Uses chemical or mechanical methods to remove or replace oxygen.

Essential for Anaerobic Microbes: Enables the study of bacteria that cannot grow in normal atmospheric conditions.

Anaerobic Culture: Anaerobic Chamber

A sealed environment with no oxygen to grow obligate anaerobes.

Anaerobic Culture: GasPak Jar:

Uses chemical reactions to remove oxygen inside a sealed jar.

Anaerobic Culture: Thioglycolate Broth

Contains reducing agents to create oxygen gradients, allowing aerobic and anaerobic bacteria to grow at different levels.

Applications of Anaerobic Culture Methods

Culturing Obligate Anaerobes: Essential for growing bacteria that cannot survive in oxygen-rich environments.

Medical Diagnostics: Identifies anaerobic pathogens in clinical samples (e.g., wound infections).

Food and Industrial Applications: Used in studying bacteria involved in fermentation and gut microbiota research.

Cell Culture (for Intracellular Bacteria and Viruses)

Used to grow microorganisms which require living host cells to replicate.

Particularly obligate intracellular bacteria and viruses,

Unlike free-living bacteria, these microbes cannot grow on standard solid or liquid media and must be maintained in living cells.

Key Features of Cell Culture (for Intracellular Bacteria and Viruses)

Provides a Living Environment: Supports the replication of microbes that depend on host cell machinery.

Controlled Growth Conditions: Uses sterile conditions, specific nutrients, and temperature regulation to sustain host cells.

Essential for Study and Diagnosis: Used for virus propagation, vaccine development, and research on intracellular pathogens.

Cell Culture: Tissue Culture

Used for obligate intracellular bacteria (e.g., Chlamydia) and viruses.

Grown in living cells, such as mammalian cell lines.

Applications of Cell Culture (for Intracellular Bacteria and Viruses)

Viral Research and Vaccine Production: Allows the growth of viruses for vaccine development and antiviral testing.

Intracellular Pathogen Studies: Helps study bacteria that require host cells to survive, aiding in understanding diseases.

Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology: Used to propagate recombinant viruses and study host-pathogen interactions.

General Purpose Media

Supports the growth of a wide range of bacteria.

Example: Nutrient agar, tryptic soy broth.

Application: Used for routine bacterial growth and maintenance.

Selective Media

Contains specific agents that inhibit the growth of certain bacteria while allowing others to grow.

Application: Used for isolating specific bacterial species from mixed cultures.

Example: MacConkey agar (selects for Gram-negative bacteria).

Differential Media

Contains indicators that allow differentiation between bacterial species based on biochemical reactions.

Application: Used to distinguish bacteria based on metabolic properties, such as lactose fermentation.

Example: Blood agar (differentiates hemolytic bacteria).

Enrichment Media

Contains nutrients that favor the growth of a specific microorganism, increasing its numbers in a sample.

Application: Used to enhance the growth of low-abundance bacteria for detection.

Example: Selenite broth (enhances Salmonella growth).

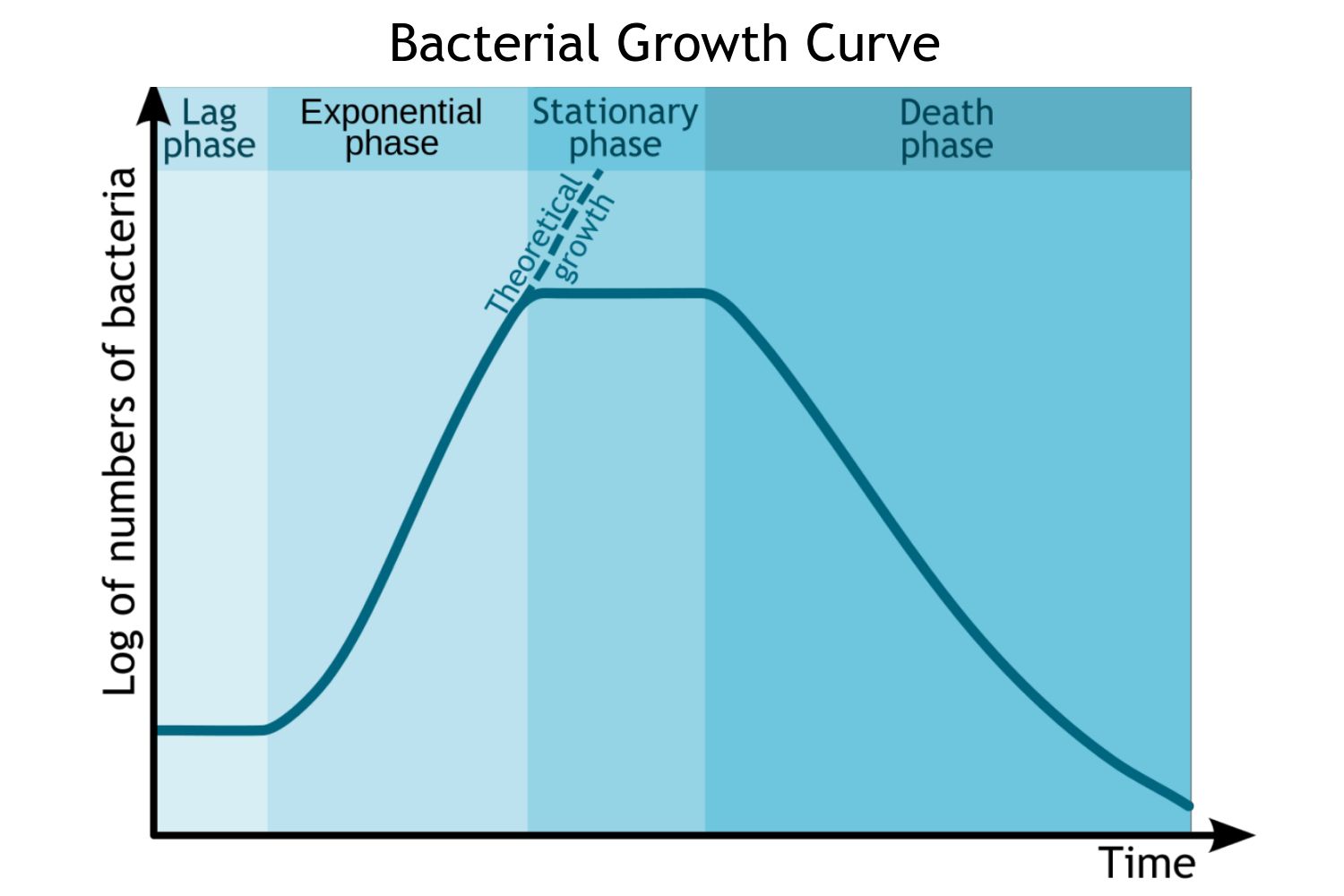

Bacterial Growth Curve

Represents the changes in bacterial population over time under controlled conditions,

Typically observed in a closed system

Ex. a batch culture in broth

Bacterial Growth Curve Stage 1: Lag Phase

What Happens?

Bacteria adjust to their new environment.

Little to no cell division occurs.

Cells are metabolically active, synthesizing enzymes and molecules needed for growth.

Key Features:

Duration varies depending on bacterial species and conditions.

No significant increase in cell numbers.

Bacterial Growth Curve Stage 2: Log (Exponential) Phase

What Happens?

Bacteria start dividing at their maximum rate through binary fission.

Population size doubles at regular intervals (generation time).

Nutrients are plentiful, and metabolic activity is at its peak.

Key Features:

Growth follows an exponential pattern.

Bacteria are most vulnerable to antibiotics and environmental changes.

This is the best phase for studying bacterial metabolism and genetic properties.

Bacterial Growth Curve Stage 3: Stationary Phase

What Happens?

Growth rate slows as nutrient levels decrease and waste products accumulate.

The number of new cells = dying cells, leading to a plateau in population size.

Some bacteria start forming endospores or survival mechanisms.

Key Features:

Bacteria become more resistant to stress (e.g., antibiotics, pH changes).

Secondary metabolites (e.g., antibiotics) may be produced.

Bacterial Growth Curve Stage 4: Death (Decline) Phase

What Happens?

Nutrients are exhausted, and toxic byproducts accumulate.

The number of dying cells exceeds new cell formation.

Some bacteria enter a dormant state, while others lyse.

Key Features:

Population size decreases over time.

Some bacteria survive longer due to spore formation or genetic adaptations.

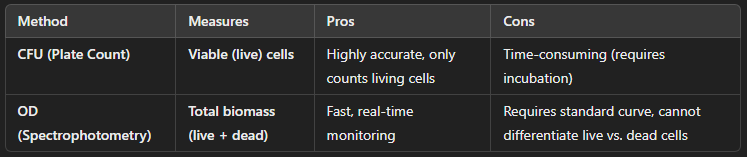

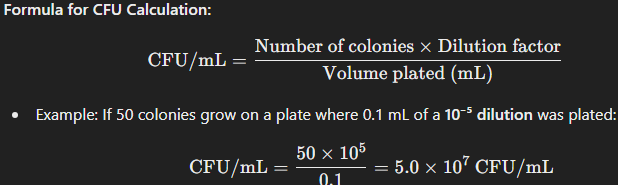

Methods for Measuring Bacterial Growth

To determine bacterial population size and growth rate, scientists commonly use plate count data (colony-forming units, CFUs) and optical density (OD) measurements.

Both methods are essential in microbiology, with CFU counts best for precise viable counts and OD measurements best for tracking population growth over time.

Plate Count Method (Colony-Forming Units, CFUs)

How It Works:

A bacterial culture is serially diluted and plated onto solid agar.

After incubation, visible colonies form, each arising from a single viable cell or a small cluster of cells.

Colonies are counted and used to calculate the original bacterial concentration.

Application:

Used for viable cell counts (only living bacteria that form colonies are counted).

Accurate for measuring bacterial concentration but requires incubation time.

Optical Density (OD) Method (Spectrophotometry)

How It Works:

A spectrophotometer measures the turbidity (cloudiness) of a bacterial culture at a specific wavelength (typically 600 nm, OD₆₀₀).

The more bacteria present, the more light is scattered, increasing the OD reading.

A standard curve correlating OD values with actual bacterial counts (CFU/mL) is needed for precise measurements.

Application:

Rapid and non-destructive measurement of bacterial growth.

Measures both living and dead cells, unlike CFU counts.

Often used in real-time growth monitoring but less accurate than CFUs for absolute counts.

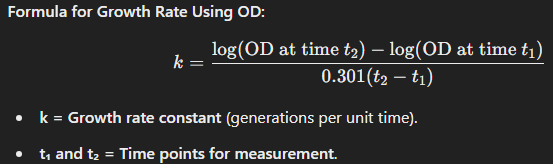

Major Classes of Antibiotics

Antibiotics work by inhibiting essential bacterial processes, preventing growth and reproduction.

Antibiotics: Beta-Lactams (Penicillins & Cephalosporins)

Mechanism of Action:

Inhibit peptidoglycan synthesis by targeting penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) involved in cell wall formation.

Weakens the bacterial cell wall, leading to cell lysis (bactericidal).

Examples:

Penicillins: Ampicillin, Amoxicillin

Cephalosporins: Ceftriaxone, Cephalexin

How do Beta-Lactams target bacterial growth?

Mainly Gram-positive bacteria, but some modified forms (e.g., cephalosporins) work against Gram-negative bacteria.

Antibiotics: Tetracyclines

Mechanism of Action:

Bind to the 30S ribosomal subunit, blocking tRNA attachment and preventing protein synthesis.

Bacteriostatic (stops bacterial growth without killing).

Examples:

Tetracycline, Doxycycline

How do Tetracyclines target bacterial growth?

Broad-spectrum (effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including intracellular pathogens like Chlamydia and Rickettsia).

Antibiotics: Fluoroquinolones

Mechanism of Action:

Inhibit DNA gyrase (topoisomerase II) and topoisomerase IV, enzymes essential for bacterial DNA replication.

Prevents DNA supercoiling and repair, leading to bacterial death (bactericidal).

Examples:

Ciprofloxacin, Levofloxacin

How do Fluoroquinolones target bacterial growth?

Broad-spectrum, effective against many Gram-negative and some Gram-positive bacteria.

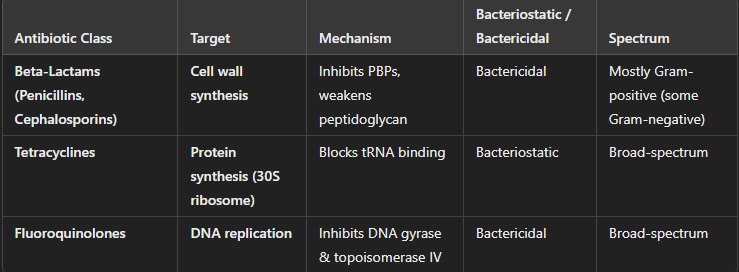

Sterilization and Disinfection Techniques

Sterilization and disinfection are methods used to eliminate or reduce microbial life in various settings (e.g., medical, laboratory, industrial).

Essential for controlling microbial growth and preventing infection, contamination, or spoilage in various industries.

Work by targeting essential cellular structures and processes, compromising microbial survival or reproduction.

Sterilization: Heat

Mechanism of Action:

Denatures proteins and destroys cell membranes, leading to cell death.

High temperatures disrupt the integrity of cellular structures and enzymes critical for microbial life.

Application:

Common in medical, laboratory, and food industries to sterilize tools and materials.

Sterilization: Moist Heat

More effective due to better penetration.

Example: Autoclaving (121°C at 15 psi for 15 minutes) for sterilizing medical equipment.

Sterilization: Dry Heat

Used for materials that cannot tolerate moisture (e.g., glassware, metal).

Example: Incineration, ovens (160-180°C for 1-2 hours).

Disinfection: Ultraviolet (UV) Radiation

Mechanism of Action:

UV light, particularly UV-C (wavelength 200-280 nm), damages DNA by forming thymine dimers, which inhibit DNA replication and transcription, leading to cell death or mutations.

Effectiveness:

Primarily effective for surface sterilization and in air or water disinfection.

Does not penetrate materials well (so mainly used for disinfecting exposed surfaces).

Application:

Common in water treatment, air purification systems, and disinfection of cleanrooms.

Disinfection: Chemical Disinfection

Mechanism of Action:

Chemical disinfectants interfere with cell membranes, proteins, and nucleic acids, disrupting microbial functions and killing or inhibiting microbial growth.

Common Chemical Agents:

Alcohols (e.g., ethanol, isopropanol): Denature proteins and disrupt membranes.

Chlorine Compounds: Oxidize cell components, killing microbes.

Aldehydes (e.g., formaldehyde): Cross-link proteins and DNA, leading to inactivation.

Phenols: Disrupt cell membranes and denature proteins.

Quaternary Ammonium Compounds (Quats): Disrupt microbial cell membranes.

Application:

Common in disinfecting surfaces, equipment, skin (e.g., alcohol-based hand sanitizers), and water treatment.

Sterilization or Disinfection: Filtration

Mechanism of Action:

Physically removes microbes from liquids or gases by passing them through a filter with pores small enough to trap bacteria, viruses, and other particles.

Does not kill the microbes but removes them from the medium.

Types of Filters:

Membrane filters (e.g., 0.22 µm for bacteria, 0.01 µm for viruses).

HEPA filters (used in air systems to remove particles larger than 0.3 µm).

Application:

Used in sterilizing heat-sensitive liquids (e.g., vaccines, antibiotics) and in air filtration systems (e.g., in hospitals or laboratories).

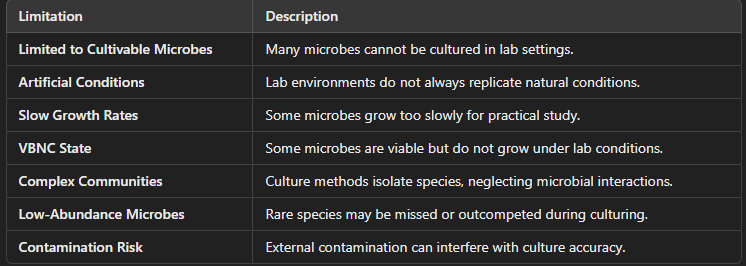

Limitations of Culture-Based Approaches to Study Microbes

…

Limited to Cultivable Microorganisms

Challenge:

Not all microbes can be cultured in the lab. It is estimated that up to 99% of microorganisms in nature cannot be cultured using traditional methods.

Reason:

Many microbes have specific environmental requirements (e.g., oxygen, pH, temperature, nutrient availability) that cannot be replicated in the laboratory.

Some organisms are obligate intracellular pathogens (e.g., certain bacteria and viruses) that require host cells for growth, which makes them difficult to culture outside of living systems.

Artificial Conditions in Lab Settings

Challenge:

Laboratory conditions, such as temperature, oxygen levels, and nutrient availability, do not always mirror natural environments.

Reason:

Many microbes live in specific, often complex, ecosystems (e.g., soil, the human gut, aquatic environments) with interactions between different species that cannot be replicated in a petri dish.

Microbial behavior may change when grown in isolation, which may not reflect their natural growth patterns and interactions.

Slow or Difficult Growth Rates

Change:

Some microbes grow very slowly or have extremely long generation times, making it challenging to observe or study them in a reasonable amount of time.

Reason:

Examples include mycobacteria (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis) or spore-forming bacteria (e.g., Clostridium species), which may take weeks or even months to form visible colonies.

In contrast, microbial growth can be much faster in natural environments where they exist in a dynamic, nutrient-rich ecosystem.

Slow or Difficult Growth Rates

Challenge:

Some microbes grow very slowly or have extremely long generation times, making it challenging to observe or study them in a reasonable amount of time.

Reason:

Examples include mycobacteria (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis) or spore-forming bacteria (e.g., Clostridium species), which may take weeks or even months to form visible colonies.

In contrast, microbial growth can be much faster in natural environments where they exist in a dynamic, nutrient-rich ecosystem.