Dutch Politics in Crisis Midterm | Quizlet

1/198

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

199 Terms

PvdA

Labour Party

- social democracy

- centre-left

- in alliance with GL

- 14/75 senators

- 25/150 reps

GL

GreenLeft

- green politics

- centre-left

- in alliance with PvDA

- 14/75 senators

- 25/150 reps

GroenLinks-PvdA (GL/PvdA)

alliance between PvdA and GroenLinks

- joint candidate list

- joint parliamentary group of 25 seats

• got more seats from D66 in 223 than 2021

- strategic voters who wanted to influence gov formation

- has only regained strategic voters

PVV

Party for Freedom

- right-wing populism

- far-right

- Leader: Geert Wilders, created after splitting from VVD

- anti immigration/Islam

- 4/75 senators

- most seats in house (37/150)

→ becomes major party in 2023

- part of coalition government

- ends decade of depoliticization

VVD

People's Party for Freedom and Democracy

- conservative liberalism

→ economic/ethical issues = liberal

→ international relations = conservative

- center-right

- 10/75 senators

- 24/150 reps

- the largest political party in the Netherlands for over a decade under the leadership of Mark Rutte

BBB

Farmer–Citizen Movement

- agrarianism (focus on agriculture)

- right-wing

- protests about nitrogen problem

- against cultural elite

- 16/75 senators

- 7/150 reps

- part of coalition government

NSC

New Social Contract

- Christian democracy

- centre-right

- derivative party of CDA

- Leader: Pieter Omtzigt

- 20/150 reps

- part of coalition government

D66

Democrats 66

- social liberalism

→ very liberal on ethical issues

- junior liberal party

- centre

- 5/75 senators

- 9/150 reps

CDA

Christian Democratic Appeal

- Christian democracy

- centre-right

- used to be dominant party/was majority

- now, dwindling support → 3% of votes

- NSC has become derivative/descendant party

- vaguer references to religion

- 6/75 senators

- 5/150 reps

LPF

Pim Fortuyn List

- right-wing populism

- anti-immgration

- Leader: Pim Fortuyn

• 2002: bc gov depoliticized and depolarized there was room for new party to create change

• after assassination, wins unprecedented number of seats

- party eventually collapses

SP

Socialist Party

- democratic socialism

- left-wing

- 3/75 senators

- 3/150 reps

FvD

Forum for Democracy

- National conservatism

- extreme right

- radicalized before and especially during COVID

- one of the largest parties in 2021 provincial elections

- now: smaller

Denk

- minority interests

- center-left

- migrant support

- 3/150 reps

- no senate

JA21

- Conservative liberalism

- far-right

- populism

- split from Forum for Democracy

socialist democrats

• start from class/labor issues

• dwindling support

• includes:

- PvdA: labor party

- SP: socialist party

liberals

• includes:

- VVD

- D66

Christian Democrats

orthodox parties

- SGP (Reformed Political Party), Christian Democracy (center)

- Christen Unie (Christian Union), Christian right (right)

ecologicals

includes:

- GroenLinks (GreenLeft), center-left

- Partij voor de Dieren (Party for the Animals), left

radical right

• common characteristics:

- usually formed out of more liberal conservative parties

- focus on nation state as organizing principle → nativist

- radical

→ still democratic

→ majoritarian

• includes:

- PVV

- FvD (Forum for Democracy)

extreme

outside of democracy

radical

within democracy

one issue, niche, new parties

includes:

- Volt

- BBB

- Denk

- JA21

junior party

smaller within party family

- often more radical

Pim Fortuyn

head and founder of LPF

- assassinated in 2002

- began wave of anti-immigration politics

- anti-immigration, pro-LGBTQ

Geert Wilders

chairman and founder of PVV (Party for Freedom)

- wasn't allowed to be PM in new coalition

- very anti-immigration/Islam

Mark Rutte

former prime minister (VVD)

- longest serving in history (13 years)

- had to resign bc of child benefits scandal

Dick Schoof

current prime minister

- no party affiliation

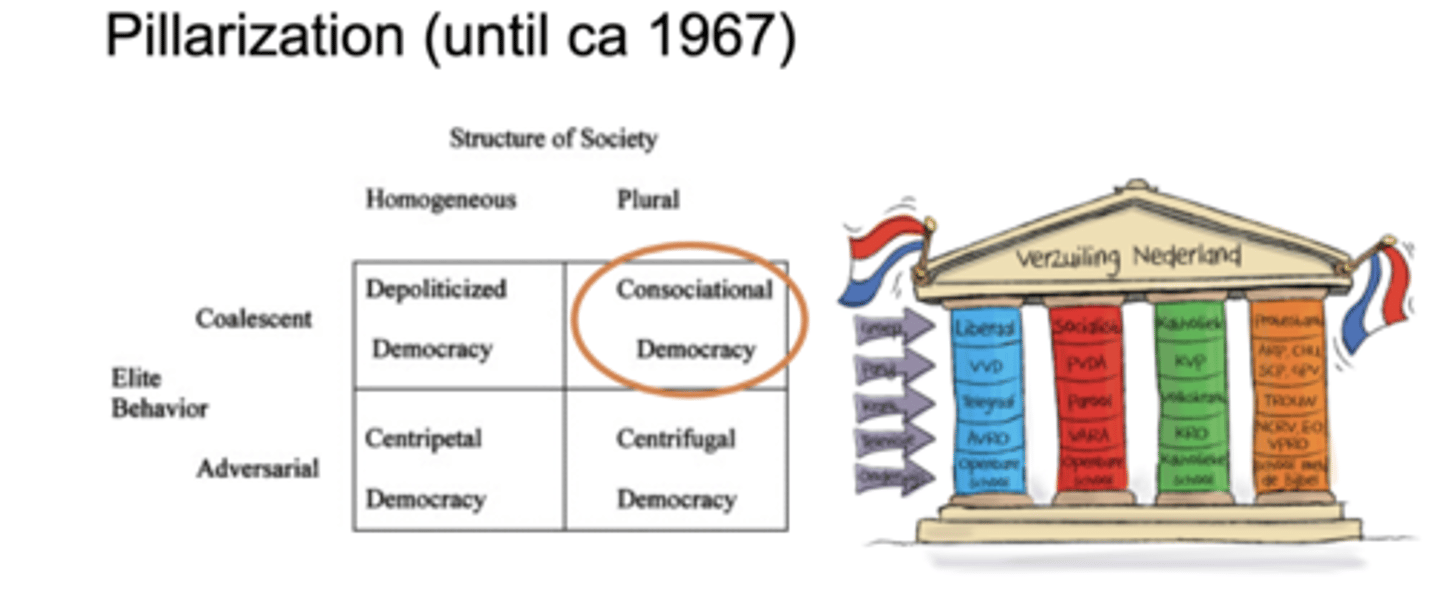

🔹 Historical Context: The Politics of Accommodation

Stability and Change in Dutch Politics - Lange, Louwerse, Hart, van Ham

🔹 The Netherlands was once seen as a model of elite accommodation, managing a deeply divided society (religious, class, regional) through consensual politics (Lijphart’s theory of consociationalism).

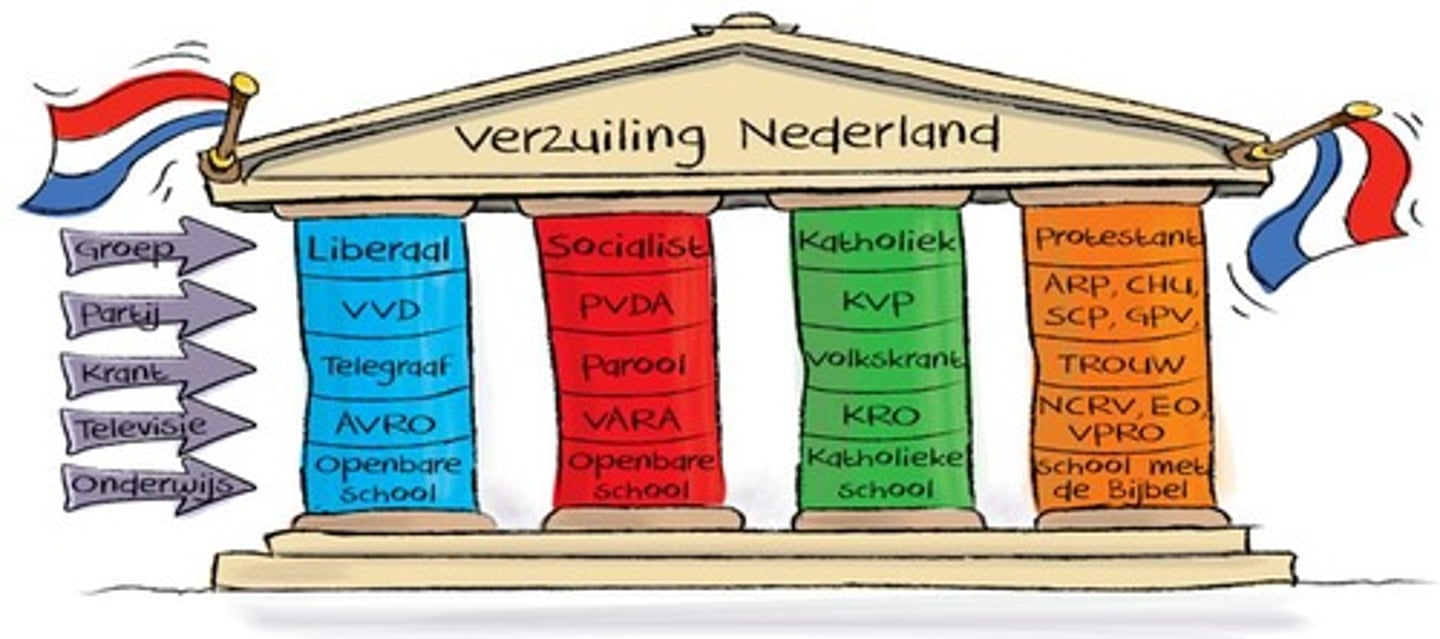

- The political system was based on pillarization, where society was segmented into Catholic, Protestant, socialist, and liberal pillars, each with its own institutions.

- This system provided stability, but began to erode from the late 1960s onward due to social change.

🔹 Recent Trends: Political Volatility and Fragmentation

Stability and Change in Dutch Politics - Lange, Louwerse, Hart, van Ham

- Since the 2000s, Dutch politics has become highly fragmented with the rise of new parties (e.g., animal rights, farmers, anti-Islam, pan-European, social justice).

- Electoral volatility has increased and centrist consensus politics have weakened.

- Parliamentary majorities are harder to form and maintain, leading to complex, lengthy coalition formations.

Fragmentation

The presence of many political parties with significant parliamentary representation.

🔹 Coalition Governance under Pressure

Stability and Change in Dutch Politics - Lange, Louwerse, Hart, van Ham

- Under long-serving Prime Minister Mark Rutte (2010–2024), governance depended on tight coalition control and pre-negotiated agreements, criticized for undermining parliamentary independence.

- The government often needed to work with opposition parties to pass legislation in the Senate, where it lacked a majority.

- Critics argue that parliament has become a symbolic stage, with real power concentrated in the hands of party elites.

🔹 Crisis of Representation and Trust

Stability and Change in Dutch Politics - Lange, Louwerse, Hart, van Ham

- Dutch citizens show declining political trust and rising affective polarization (hostility between social and political groups).

- Institutions face performance pressure: legitimacy now depends more on results and accountability than on tradition or elections alone.

- Implementation failures and inquiries (e.g., childcare benefits scandal) have further eroded trust.

🔹 The 2023 Realignment Election

Stability and Change in Dutch Politics - Lange, Louwerse, Hart, van Ham

- The 2023 election marked a turning point: Geert Wilders’ PVV (radical-right) won a surprise victory.

- The PVV's win reflected public anxiety over migration, crises in governance, and a desire for political change.

- The coalition formed in 2024 includes the PVV and marks a significant shift in Dutch politics toward the right.

🔹 Structural & Societal Changes

Stability and Change in Dutch Politics - Lange, Louwerse, Hart, van Ham

- Dutch society is now ethnically diverse, more educated, and more secular.

- Former social divisions based on religion and class have been replaced by divides along education, geography, and ethnicity.

- Political governance has moved from centralized planning to decentralized networks, complicating accountability and efficiency.

🔹 Institutional Continuity

Stability and Change in Dutch Politics - Lange, Louwerse, Hart, van Ham

- Despite social and political upheaval, core institutions (e.g., proportional representation, coalition governance) remain intact.

- The system adapts rather than reforms—proposals for institutional overhaul (e.g., electoral or democratic reform) often stall.

🧭 Big Question: What Comes Next?

Stability and Change in Dutch Politics - Lange, Louwerse, Hart, van Ham

- Dutch politics appears caught between a legacy of accommodation and growing politicization and fragmentation.

- The authors stress that change is incremental and complex, with moments of crisis driving adjustments rather than wholesale reform.

“The Rise and Fall of Dutch Consociationalism” - Andeweg

1. Consociationalism in the Netherlands

- The Netherlands is considered the first consociational democracy: a political system in which elite cooperation ensures stability in a segmented society.

- The Pacification of 1917 is seen as the start of this system

2. Pillarization (Verzuiling)

- Dutch society was divided into “pillars”: Catholic, Protestant, Socialist, and Liberal subcultures. These pillars had autonomous institutions like media, schools, unions, and parties.

- elites cooperated through "politics of accommodation"

3. Criticism of the Theory

- Some argue pillarization wasn’t a grassroots phenomenon but a top-down strategy of social control by elites to consolidate their power.

- Others see it as a response to modernization and industrialization, where elites pre-empted class conflict by organizing along religious lines.

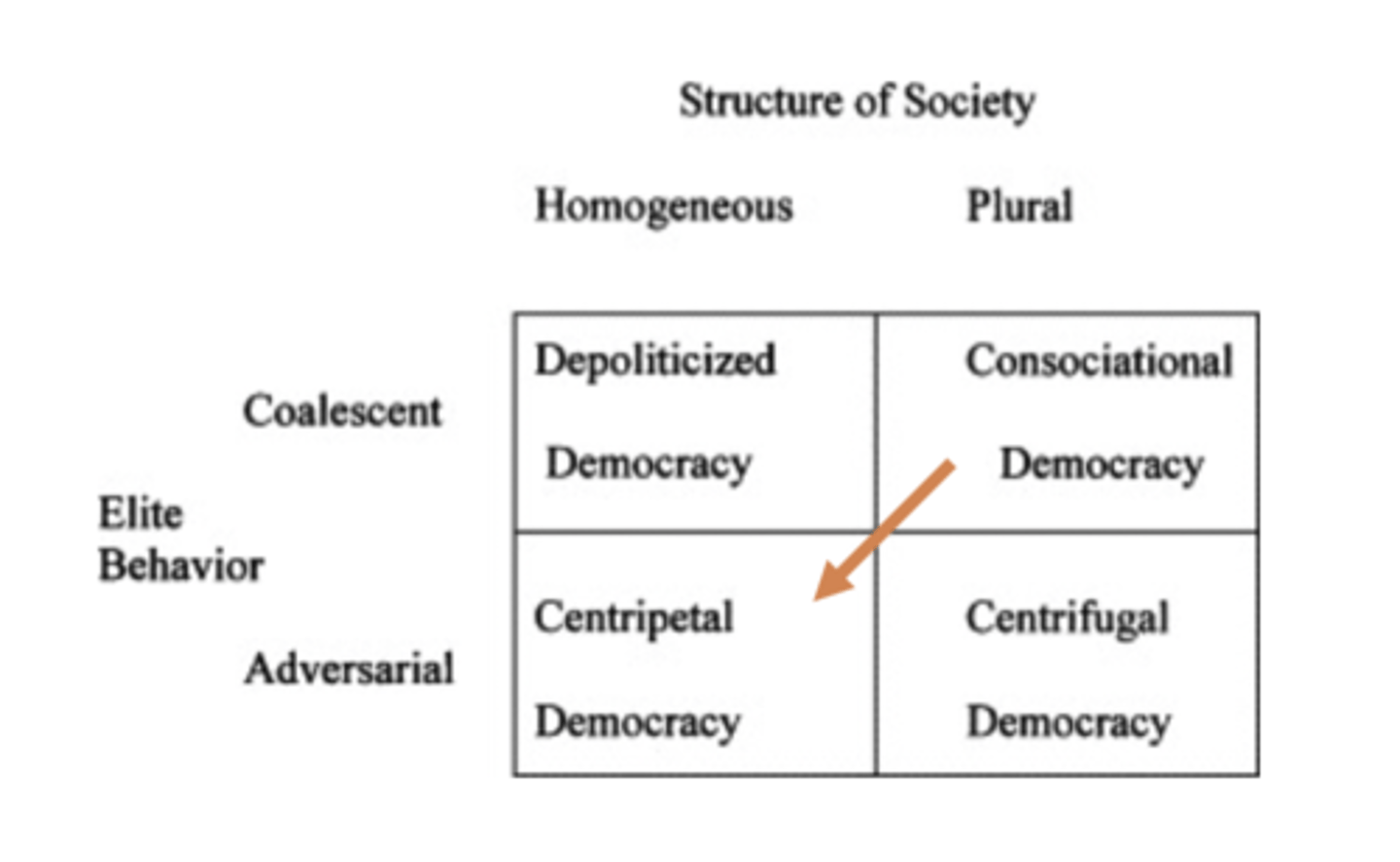

4. Depillarization (Starting ~1960s)

- Pillars weakened due to secularization, social mobility, and changing media/education.

- Party loyalty declined, and cross-pillar mergers began.

- Depillarization didn’t produce isolated individuals, but more fluid and mixed affiliations.

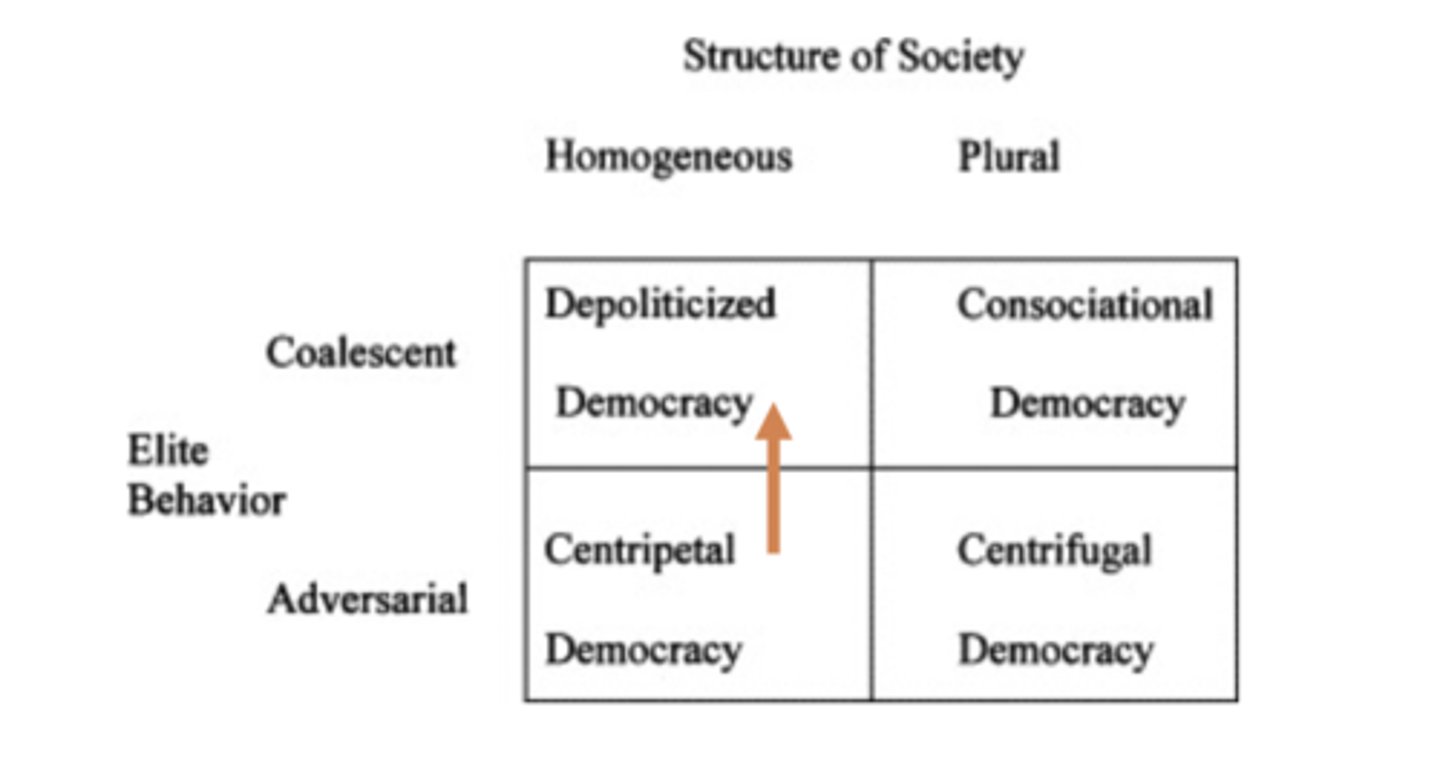

5. Post-Pillarization Politics

- Even after depillarization, elite cooperation persisted—leading to “cartel democracy”, where mainstream parties govern together and exclude others.

- This can breed voter resentment, especially among those who feel excluded from mainstream politics—creating space for populist parties like PVV and FvD.

6. Populism and the Crisis of Representation

- The absence of meaningful choice (due to elite consensus) may push voters to anti-system parties.

= Dutch politics may be caught in a “vicious cycle”: weak centrist parties → populist rise → less consensus → more fragmentation.

Lijphart’s Four Principles of Elite Cooperation

“The Rise and Fall of Dutch Consociationalism”

- Segmental autonomy: Pillars govern their own members.

- Mutual (minority) veto: Pillars can block decisions threatening core values.

- Grand coalition: All major segments are included in governing coalitions.

- Proportionality: Resources and political power are distributed in proportion to pillar size.

Consensus Democracy

Consensus Democracy in the Netherlands

Philip van Praag

- commitment to negotiation, compromise, and cooperation—especially among elites.

- Based on three types of consensus:

1. Substantive: Agreement on policy content.

2. Institutional: Agreement on the structure and rules of the political system.

3. Procedural: Agreement on how political differences are resolved.

2. Origins and Historical Roots

- The Dutch model of consensus was deeply shaped by pillarization

- Key informal rules included summit diplomacy, proportionality, depoliticization, and secrecy

3. Institutional Model of Consensus Democracy

- Based on Lijphart’s typology

→ Consensus democracy: Broad coalitions, proportional representation, bicameralism, federalism.

→ Majoritarian democracy: One-party governments, first-past-the-post systems, centralized power.

Challenges to consensus Democracy

Consensus Democracy in the Netherlands

Philip van Praag

4. Challenges Since the 1960s

- The decline of pillarization, secularization, and individualization challenged traditional elite-driven consensus.

- Political parties like D66 and PvdA began calling for clearer electoral mandates, pre-election coalition declarations, and electoral reform.

- The polarization strategy sought to replace post-election compromise with programmatic clarity before elections.

5. Fortuyn and the Breakdown of Substantive Consensus

- Pim Fortuyn's rise in 2002 marked a turning point:

- Shift away from businesslike politics toward emotional, populist rhetoric.

- Emergence of new divisions in Dutch society

6. Limited Institutional Reform

- Despite pressures, the institutional core of consensus democracy remains intact:

- The electoral system based on proportional representation

- Reforms like the advisory referendum and parliament-led cabinet formation have had only marginal impact.

- The Socio-Economic Council (SER) continues to play an influential role despite diminished authority.

7. Return and Reinvention of Rules

- in the 1980s-90s, the consensus model saw a partial return:

- Renewed summit diplomacy (leaders of coalition parties—especially during times of conflict or government formation—negotiate compromises outside of formal parliamentary procedures), emphasis on proportionality, and limited cabinet reshuffles without elections.

- New norms emerged: the PM now typically comes from the largest governing party, and snap elections follow cabinet crises.

8. Contemporary Problems

- Political fragmentation and decline of traditional parties (e.g., CDA, PvdA) have made coalition formation harder.

- Rise of parties like PVV (right) and SP (left), which refuse to compromise on core issues, undermines coalition logic.

- Consensus among voters has eroded,

9. Future

-Though under strain, consensu

Government crisis (2023-2025)

Dutch crises

• 2023 election

- PVV (Freedom Party) becomes largest in house

- Wins of the Farmer

Citizens Movement (BBB), the Freedom Party (PVV), and NSC

→ NSC enters for first time

• parties have to form coalition: cold sentiment, parties that haven't been in government before, new PM (not member of any parties), public fight, infighting between. housing/immigrant ministers, immigrant minister wants to propose rules by decree rather than law

civic unrest (2019-2022)

Dutch crises

• protests

• policy problems:

- tax benefits scandal

- gas drilling

- farmers and nitrogen

- refugee housing

child tax benefits scandal

Dutch Tax and Customs Administration falsely accused tens of thousands of families—many of whom had dual nationalities or migration backgrounds—of fraudulently claiming childcare benefits.

families were ordered to repay tens of thousands of euros

- many lost their homes, jobs, and relationships

- over 1,600 children were placed into foster care

the Dutch government resigned on January 15, 2021

pillarization

Catholic

Protestant

Socialist

Liberal (or General)

- citizens, politicians, media

social and political life highly divided by pillar

- had its own media, schools, unions, and even sports club

Why did Dutch democracy survive pillarization?

citizens

cleavages underlying pillars overlap

- ex: religion vs social class

Why did Dutch democracy survive pillarization?

systems

consociationalism as first line of defense

- pillars have to cooperate

consociationalism

a form of government that emphasizes power sharing through guaranteed group representation

- bicameralism: must collaborate

- constitution: minorities can veto change so prevents overreach

- proportionalism

- power dispersion

Why did Dutch democracy survive pillarization?

elites

political culture of consensus

- substantive

- institutional - forced to collaborate bc of things like proportionalism

- procedural

- preserve selves thru collaboration

- plans made by pillars themselves. if not, ensure each pillar has veto power and assign power proportionally.

Explanations

social control vs class cleavages: elites have similar incentives to control working class

- collaboration makes sure socialist revolution doesn't happen

continuation of older practices: since middle ages, citizens have had to collaborate. no centralized power

self-denying prophecy: elites smart enough to realize that if they didn't collaborate it would cause civil war

country of minorities: no majoritarianism

the great pacification (1917)

• WWI: Dutch are neutral → try to resolve tensions

• push to increase the right to vote for whole male population

• Christian parties (Catholic/Protestant) want funding for their private schools

• liberals (group most active in politics) get proportionalism (end of majoritarianism)

Constitution of Thorbeck

strengthening of Parliament → dominant power in politics

cementing dualistic approach toward institutional and political dualism

the Dutch Republic

1. Revolt out of conservatism (want things to stay the same - Spanish King, just not higher taxes)

2. Lack of a unitary state and an absolute sovereign

3. Diversity as a fact and as a norm

4. Elite tradition of 'schikken en plooien' (finding compromise) - no majorities

5. Weak central bureaucracy

6. Weak executive

7. Bourgeoisie within a calvinist understanding

8. Good governance with stable international trade

purple government

coalition governments formed in the 1990s and early 2000s that united the red (social-democratic) and blue (liberal) political camps

- The Labour Party (PvdA) – center-left, social-democratic (red)

- The People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) – center-right, liberal (blue)

- The Democrats 66 (D66) – centrist, progressive-liberal

period of depoliticization

result from brief eras of polarization/contentions

changing norms of political elites

1. From Consensus to Conflict (and Partial Return)

- 1968: Dutch politics was governed by consensus and depoliticization, hallmarks of consociational democracy.

- 1974: A shift begins — conflict, polarization, and politicization emerge, challenging the older elite agreement style.

1993–2017: Partial reversion to consensus tools (e.g., “agreement to disagree” reappears), but conflict on divisive issues (immigration, EU) and emotional politics also take root.

2. Increased Politicization of Governance

- Over time, there's a growing politicization of government composition.

- While in 1968, the government ruled with little parliamentary interference, by the 1990s and 2000s, there's increased emphasis on political maneuvering, party control, and symbolic politicization.

- Yet, some formal rules (e.g., PM comes from the largest party) remain stable.

3. Changing Nature of Openness and Secrecy

- From secrecy in Lijphart’s era to open government in the 1970s, shift toward strategic or restricted openness in recent years — leaders may appear open but still manage information tightly (“open image building”)

4. Proportionality & Summit Diplomacy as Enduring Norms

- Despite changes in tone and behavior, the Dutch system has retained proportional representation and a form of selective summit diplomacy — elite negotiation still matters, though more selectively than in the early days of consociationalism.

5. Rise of Emotional and Populist Politics

- “businesslike and emotional politics” — reflecting the rise of populist figures like Geert Wilders and the broader global trend of emotionally charged political discourse.

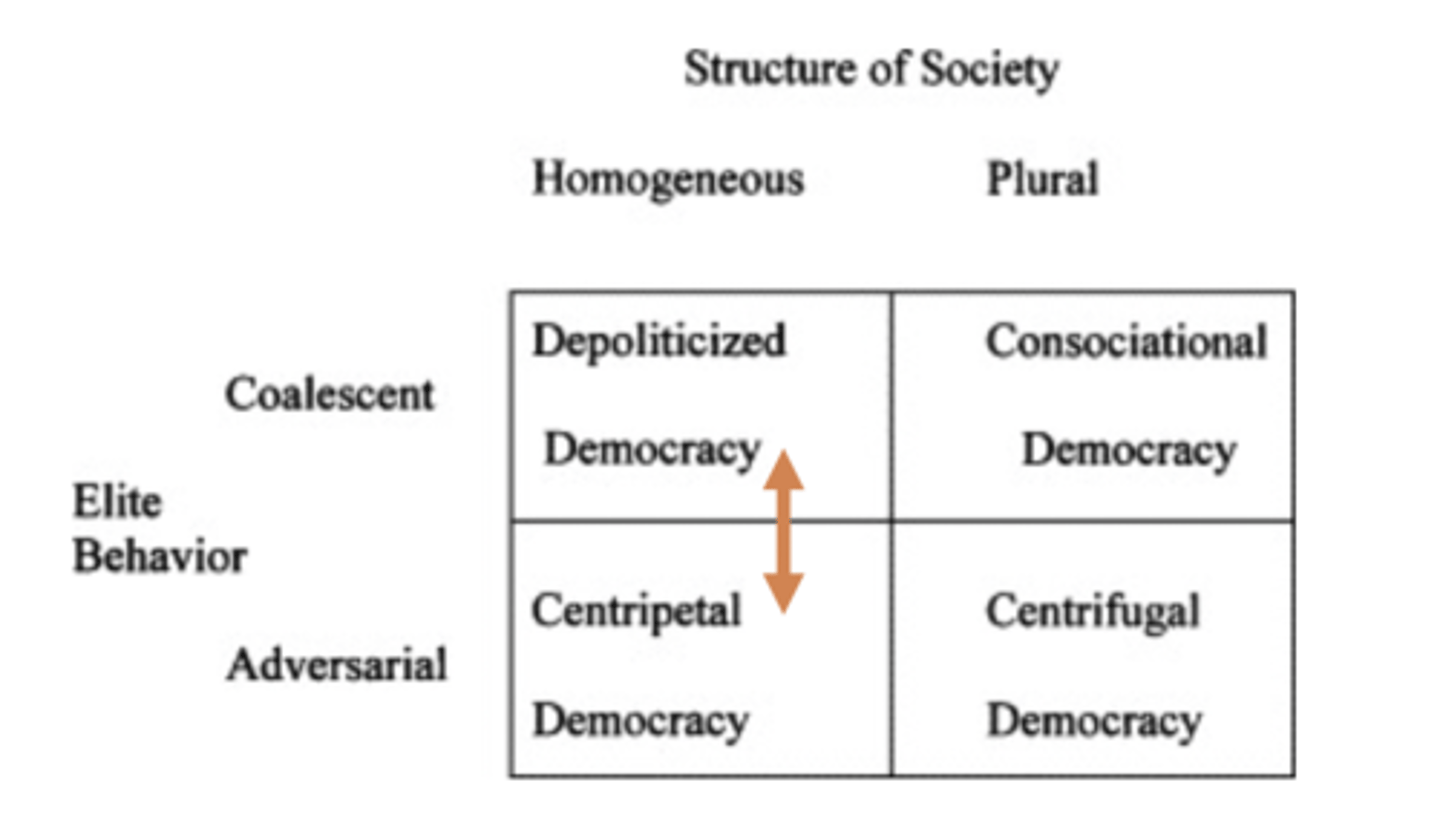

depoliticized, consociational, centripetal, centrifugal democracy

the Dutchification of politics

• Decline of traditional (government) parties

- rise in challenger parties

• Rise of one-issue parties

• Political fragmentation

• Electoral volatility

- voters shift parties

• Broad coalitions

- multiple parties

• Difficult and long coalition negotiations

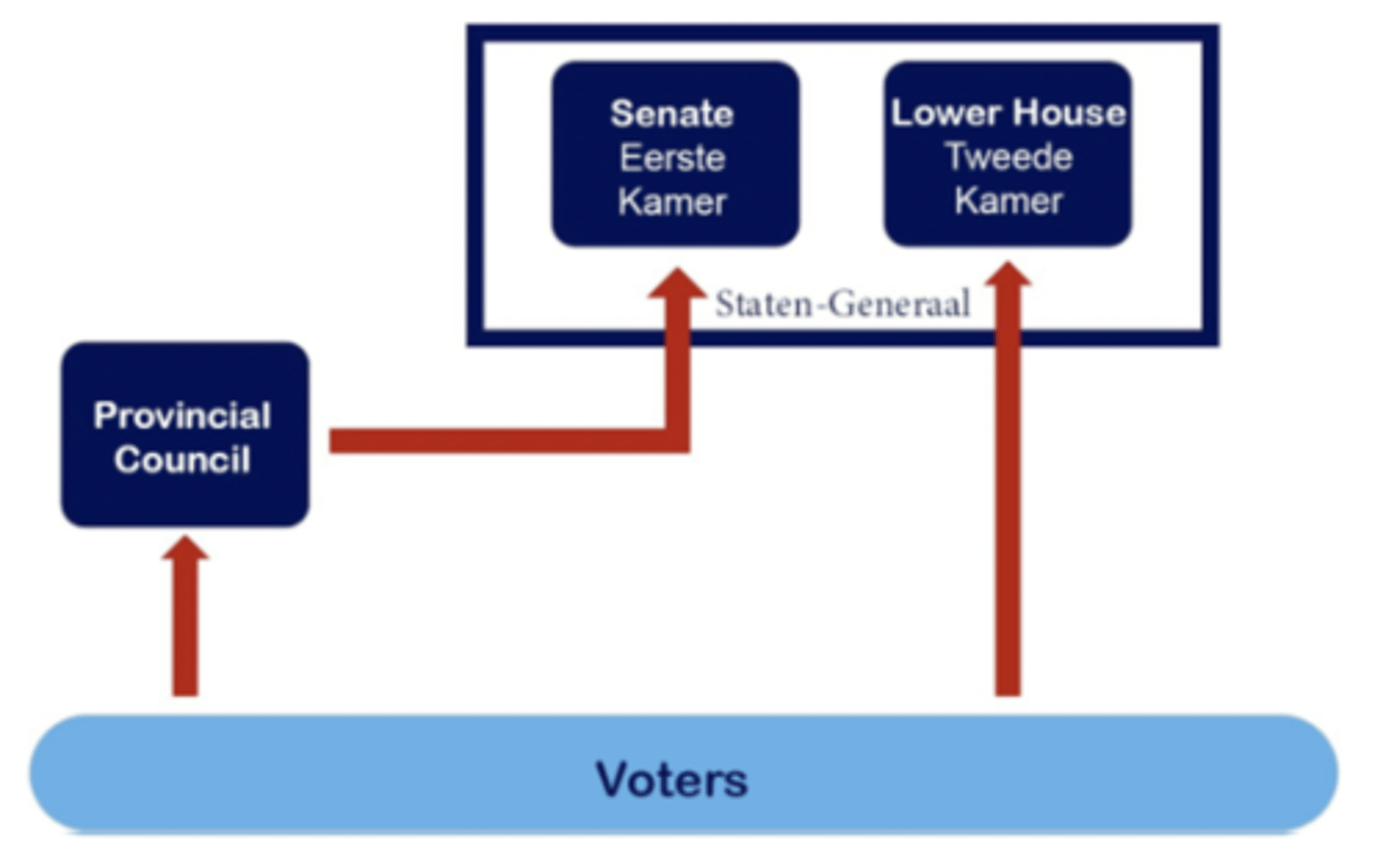

Dutch democracy institutionally

• Radically proportional, single district

• Bicameral

• Little/no block politics

• Partial monism

• Culture of collaboration

• Hard constitution, yet some of the most important norms are unwritten

• Primacy of politics: no constitutional court or test

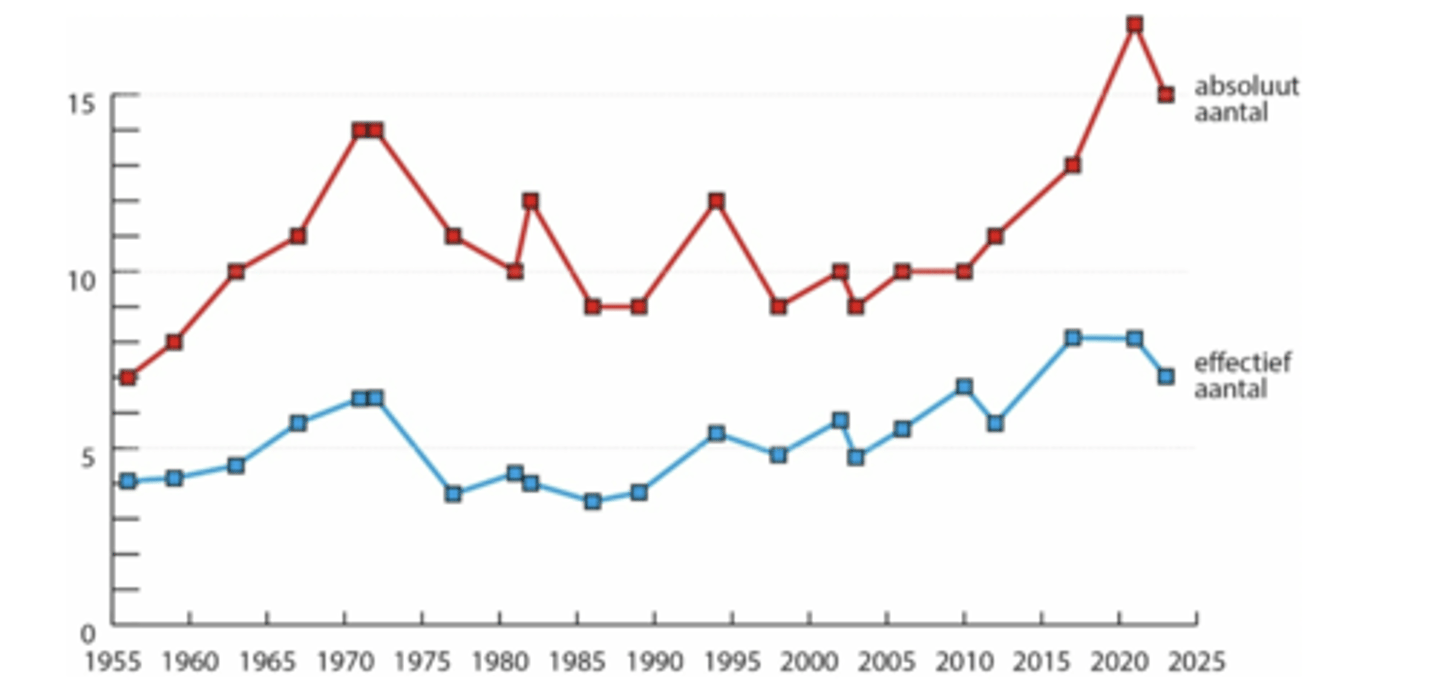

"The ever-changing and ever-stable Dutch party system" - Otjes, Lange

1. Dutch Party System: A Unique Case of Fragmentation

- The Netherlands has an extremely fragmented party system, with a high number of parties in parliament and frequent entry of new ones.

- This fragmentation results from:

→ A proportional representation electoral system with low thresholds.

→ Decline of the traditional "pillarized" party families (Christian democratic, liberal, and socialist).

→ Rising voter volatility and weakening partisanship.

2. Traditional and New Party Families

- Established party families include:

→ Christian democratic (e.g., CDA)

→ Liberal (e.g., VVD, D66)

Socialist/social democratic (e.g., PvdA, SP)

- New party families include:

→ Populist and radical parties, both on the right (e.g., PVV, FvD) and left (e.g., SP in its earlier years)

→ Issue-based parties (e.g., Party for the Animals, 50PLUS)

3. Numerical and Spatial Characteristics

Figures show a dramatic rise in the number of effective parliamentary parties since 1989.

- The three traditional core parties (CDA, PvdA, VVD) have seen a steady decline in their combined seat share.

- Dutch politics is now two-dimensional:

Economic axis (left–right) and Cultural axis (libertarian–authoritarian or cosmopolitan–nationalist)

4. Polarization Trends

Cultural and moral polarization has increased significantly

- Economic polarization has stayed relatively stable.

- culture is now a more dominant dividing line than economics.

5. Government Formation and “Partial Alternation”

- Despite fragmentation, many coalitions follow patterns of partial alternation: new governments often include at least one party from the previous coalition.

- This leads to limited change in policy direction, even with the inclusion of new or populist parties.

- Government formation has become more complex and lengthy, requiring negotiation across deep ideological divides.

Schattschneider–Mair Thesis

“Fortuyn’s Legacy: Party System Change in the Netherlands” - Pellikaan, de Lange, and van der Meer,

- Party systems are structured around dominant conflict lines

- Established parties try to freeze these conflict lines to protect their positions.

- New parties that successfully introduce new lines of conflict can reshape the party system.

“Fortuyn’s Legacy: Party System Change in the Netherlands”

Pellikaan, de Lange, and van der Meer

1. Abrupt Party System Change in 2002

- rise of Pim Fortuyn’s party (LPF) and its entry into parliament in 2002 abruptly transformed the Dutch party system.

- Unlike most European countries where populist parties rose gradually, the Dutch case was sudden and radical.

- Fortuyn introduced a new line of conflict: the cultural dimension, reshaping political competition.

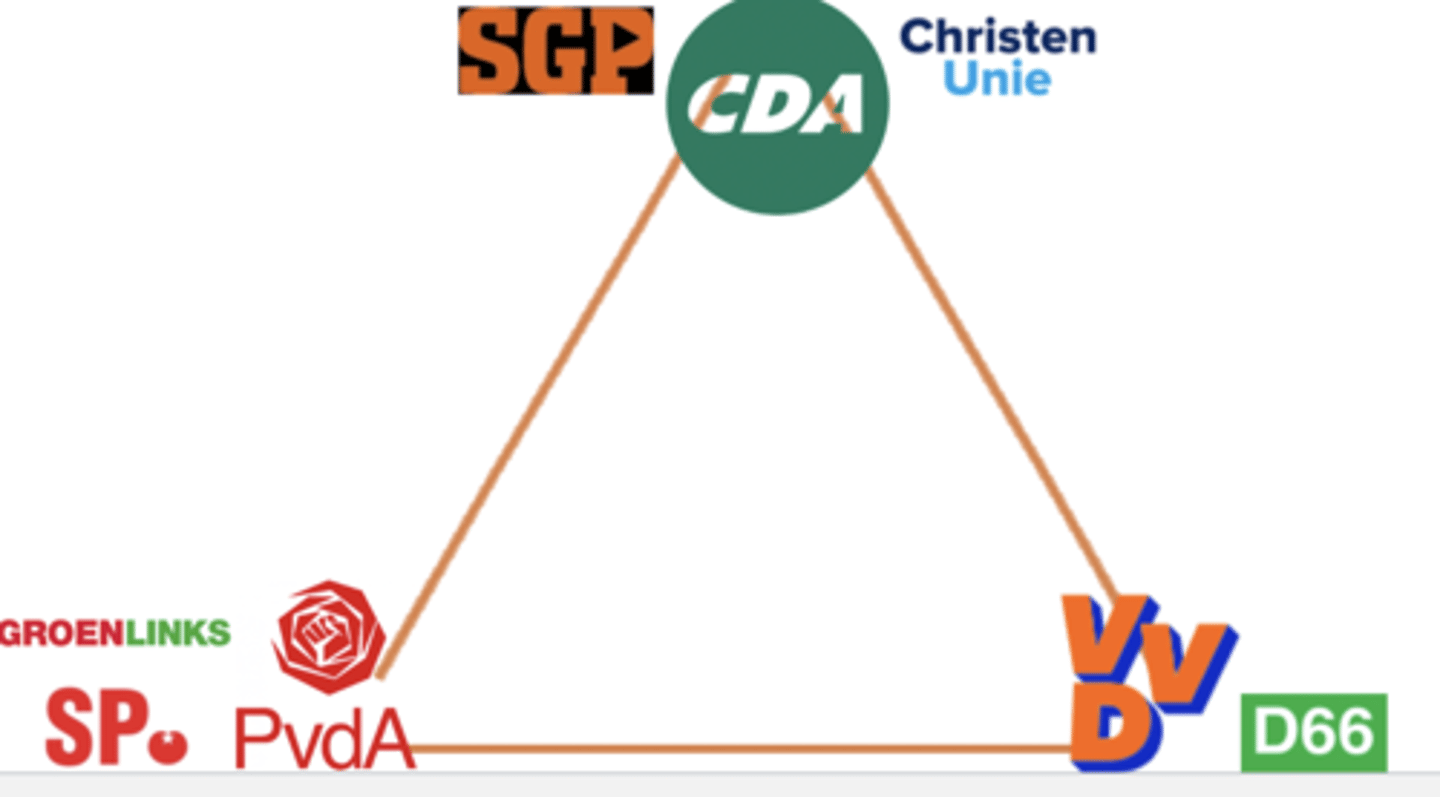

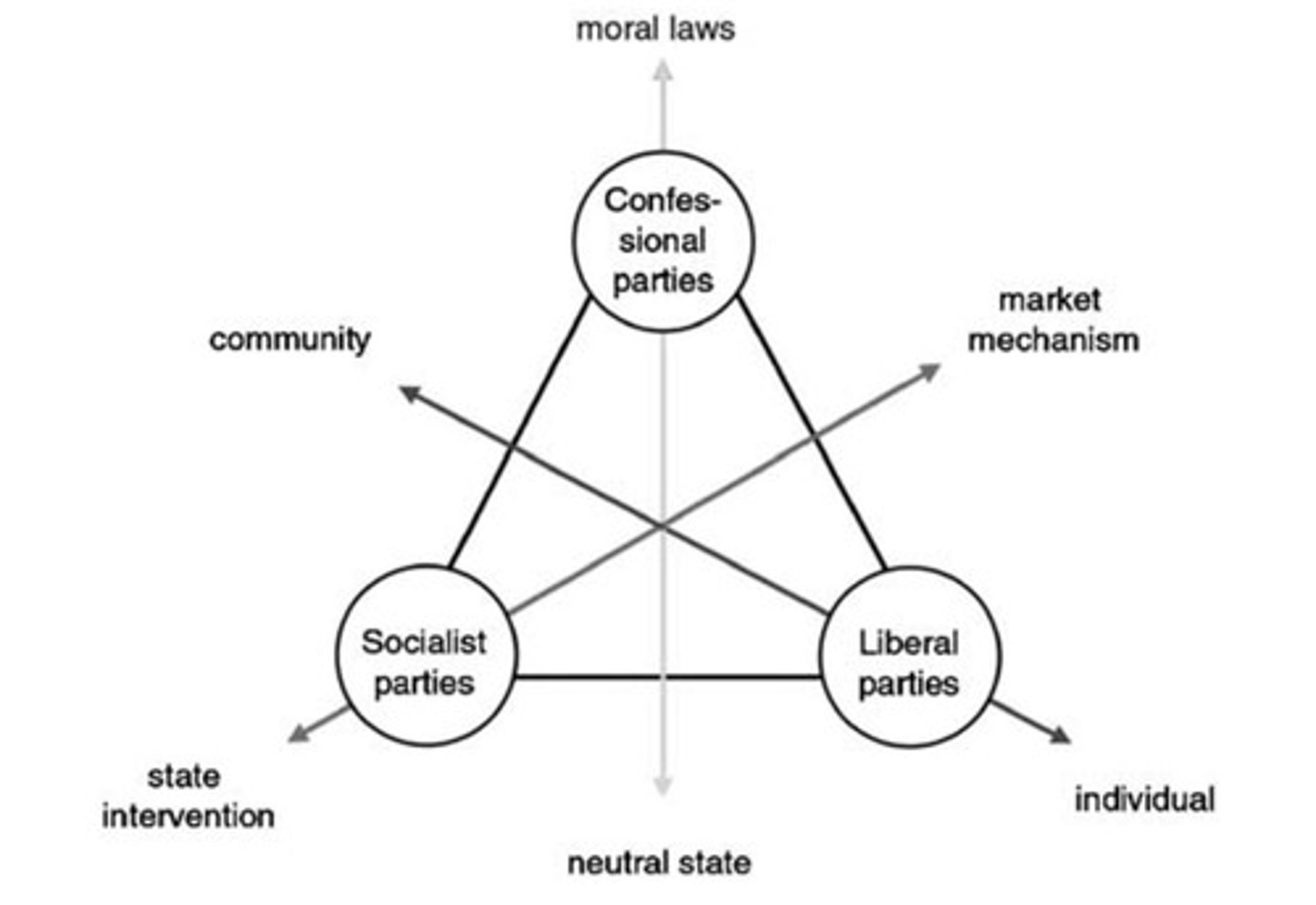

2. The “Dutch Triangle” and Its Collapse

- The traditional Dutch party system was structured around three ideological dimensions:

1. Economic (state-led vs. market economy)

2. Ethical (moral state vs. neutral state)

3. Corporatist/Communitarian (collectivist vs. individualist)

- The “triangle” was stable for decades, with socialist, liberal, and Christian parties each occupying a corner.

- The Purple coalition (1994–2002) (PvdA, VVD, D66) erased the ethical line of conflict by legalizing euthanasia and same-sex marriage.

Without this line, the triangle collapsed, paving the way for new conflicts to emerge.

3. Cultural Conflict and Immigration

- Fortuyn introduced a cultural dimension centered on national identity and integration of immigrants.

- represented state nationalism: inclusion based on shared cultural values rather than ethnicity.

- LPF success forced traditional parties to adopt his rhetoric, thereby legitimizing the new cultural dimension.

4. Two-Dimensional Space of Competition

The post-2002 party system operates in a space defined by:

1. An economic dimension (left–right)

2. A cultural dimension (monoculturalism vs. multiculturalism)

- This model allows for a clearer distinction between parties like: LPF (right-economically, strong monocultural), VVD (right-economically, moderate monocultural), SP/GL/D66 (left-economically, multicultural)

“The Dynamics of Voters’ Left/Right Identification: The Role of Economic and Cultural Attitudes”

Catherine E. de Vries, Armen Hakhverdian, and Bram Lancee

1. Left/Right Identification is Dynamic

- Traditionally, voters’ identification as "left" or "right" was rooted in economic attitudes—support for or opposition to redistribution.

- Over time, however, cultural issues—especially immigration—have become increasingly important in shaping this identification in the Netherlands (1980–2006).

- The meaning of "left" and "right" is not fixed, but shifts with political developments and elite cues.

2. Two Key Mechanisms: Issue Bundling and Issue Crowding Out

- Issue Bundling: When a new issue (like immigration) becomes politically salient, parties integrate it into their ideological platforms. Voters follow these cues and adjust their own identification accordingly.

- Issue Crowding Out: As new issues (e.g., anti-immigration sentiment) gain prominence in left/right discourse, traditional issues (like redistribution) become less central.

3. Empirical Findings (1980–2006, Netherlands)

⭐ Anti-immigrant attitudes became increasingly associated with right-wing identification.

Redistributive attitudes became less predictive of left/right placement.

- However, economic issues remain relevant, just less dominant.

4. Elite Influence and Cognitive Shortcuts

- Voters often take cues from parties to simplify political complexity.

- This means party rhetoric and issue framing strongly influence how voters position themselves ideologically.

- The rise of parties like LPF and PVV helped push immigration to the core of Dutch political competition.

"Dealignment, realignment and generational differences in The Netherlands"

Wouter van der Brug & Roderik Rekker

1. Generational Replacement Drives Electoral Change

- People form their political identities during formative years (ages ~12–25).

- These identities remain relatively stable, so political change often results from younger generations replacing older ones.

2. Dealignment vs. Realignment

- Dealignment: Traditional voting predictors like religion and class become less influential, without being replaced by new long-term factors.

- Realignment: Old predictors lose relevance but are replaced by new stable predictors like education or cultural attitudes (e.g., immigration, European integration).

2. Key Findings

⭐ Education, immigration, and EU attitudes are stronger predictors for younger generations → evidence of realignment.

⭐ Religion and social class weaken but aren't replaced in older cohorts → evidence of dealignment.

⭐ Left–right remains important, especially for those socialized in the 70s–80s, but weakens over time.

⭐ Immigration matters more for younger generations but doesn't increase linearly over time.

3. Conclusion

⭐ Both dealignment and realignment are occurring.

- Period-based change = dealignment.

- Generational change = realignment.

- Younger generations increasingly structure vote choice around new cultural cleavages, but party systems have yet to fully adapt.

conflict

different interests and goals that need to be resolved

- key and inherent to democracy

questions about conflict

1. Which conflicts are politicized?

2. Who/what are the most important actors?

3. Who benefits from conflict?

conflict: until 1967

pillarization

- consociational democracy

- people didn't change parties

conflict: competition

increased competition

- many parties

style of conflict: 1971-1982

Politicization & Depillarization

centripital democracy → adversarial

conflict: 1986-2002

Depillarization & Depoliticization

2002: Decade of depoliticization

conflict: 1994-2002

Weakened ideological triangle (and lines of conflict)

Purple government (PvdA-VVD-D66)

Consequences for:

- Economic conflict (didn't emphasize these differences)

- Ethical conflict (no Christian/non-secular parties to block)

- Conflict for Prime Ministership

conflict: 2002-2023

Temporary adverserialism

three lines of conflict

1. power

2. policy

3. dominant conflict lines

three lines of conflict: power

- prime ministerial elections

→ debate over who will be PM, political parties campaign on being next PM

- establishment vs challenger

→ establishment: mainstream political parties, traditional media, longstanding institutions, bureaucratic elites and technocrats

→ challenger: right wing/populist parties, parties challenging status quo → challenge legitimacy of establishment

three lines of conflict: policy

specific policy debates

- substantive positions

- (e.g. immigration or wellfare state)

- over time, attitudes remain stable on issue areas (don't explain volatility in vote choice)

three lines of conflict: dominant conflict lines

• conflict about what dominant conflict is

- what do we need to discuss/fight about?

⭐ structure political competition

⭐ includes frames to understand societal developments and policy problems

⭐ define policies, coalitions, and alternatives

- ex: is housing crisis a economic, social, or immigration issue?

* major part of politics in the Netherlands

battlefield of conflict (pre-2000)

2 dominant conflicts:

⭐ Economics

- redistribution v deregulation

⭐ Ethics:

- Christian values vs secularism

ideological triangle

issue absorption

parties want to absorb issues into conflict line

- ex: immigration was economic problem and now more of a cultural problem

→ strengthened the line of conflict

____

The real essence of a party system may be seen notin the competition between the principalprotagonists, be they Labour and Conservative,Christian Democrat and Social Democrat, orwhatever, but rather in the competition betweenthose who wish to maintain that principal dimensionof competition, on the one hand, and on the otherhand, those who (...) are trying to establish a whollydifferent dimension.

battlefield of conflict (post-2000)

huge restructuring

2-dimensional cleavage:

- economic: left wing and right wing

- cultural: monoculturalism vs multiculturalism

→ pro migration and internationalization vs anti-migration and pro-nation state

alignment

policy stances that parties offer align with policy preferences and views of voters and society

- economics

dealignment

Ethics: parties have decreased their focus on ethics bc it has decreased its resonance with voters

economics: importance is waining

realignment

culture

major change in conflict post-2000

⭐ an increase in importance of cultural conflict

- used to be an economic focus

- parties with strong stance on culture have strengthened/grown

Absorption

- Immigration

- Multiculturalism

- EU

- Climate

- Trust in politics

- COVID-19

rise of cultural conflict

1. Politicians: No visible cultural conflict between 1998 and 2002

- Voters saw immigration as a salient theme

2. no active debate about immigration and weak line of conflict on economics creates opening for new party

3. political entrepreneur Pim Fortuyn

- challenges elites

- immigration as cultural problem

- assassinated

Why the cultural conflict stayed salient:

• Global development → External events

• Voter salience

• Response by political parties and media

• Absorption

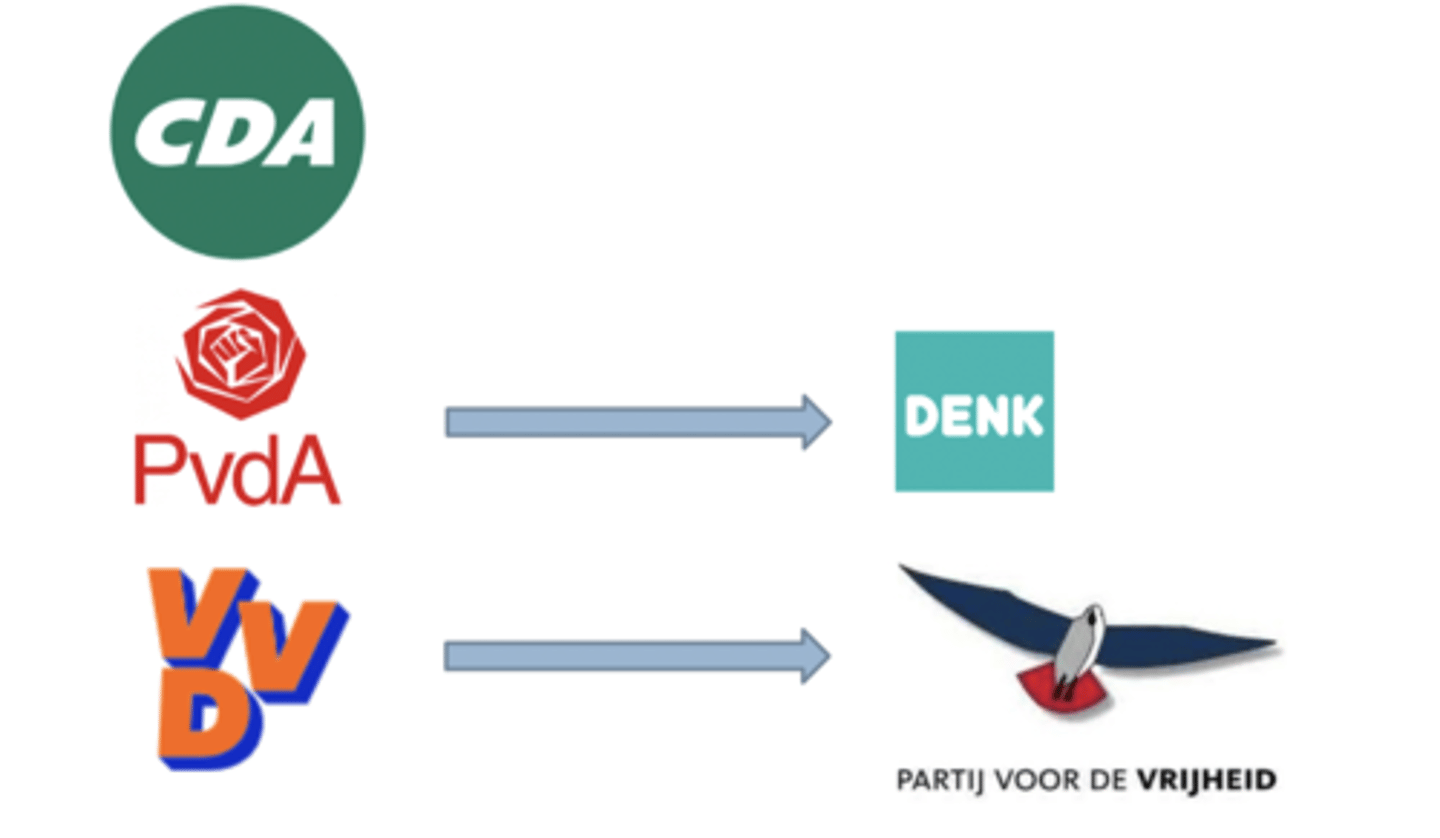

Traditional parties & cultural

conflict

• CDA: center - positioned between the more progressive parties (like PvdA) and hardline anti-immigration parties (like PVV)

• PvdA can't deal with it, flip flops stance

→ Denk emerges as a breakaway, representing immigrant and Muslim communities, particularly critical of assimilationist and anti-immigration rhetoric from mainstream parties

- immigrant and minority voters feel abandoned by the mainstream left and move toward parties that explicitly defend multiculturalism and minority rights

• VVD: most successful of mainstream parties but can't compete with radical right

→ PVV: Far-right populist party led by Geert Wilders, known for anti-Islam, anti-immigration stances splits of from VVD and gets support from former VVD and working-class voters disillusioned with multiculturalism

2023 election

• Freedom party (PVV) becomes very successful

- was losing support then surged at the end right before election

- runs line of conflict

- voters vote based on immigration (salient issue)

• occurred after over decade of depoliticization

- weakened conflict lines:

→ 2012-2017: VVD-PvdA - austerity

→ 2017-2023: VVD-CDA-D66-CU

- Economic conflict

- Cultural conflict - different views on immigration

- COVID19

- Technocratic governance: what is good for NE, not ideological

- Conflict for Prime Ministership

Centrist, technocratic governance stimulated three types of opposition

- Against TINA

→ gov says there is no alternative to agriculture policy, increasing the power of farmers party (BBB)

- Against executive

→ NSC increases in success, identifying as opposition to technocratic government

- Against centrism

→ gives space to policies against center → one single block of elites doesn't serve voters → more success of Freedom party

2023: cultural conflict - immigration

Voters: Salient, but not the most salient theme

Policy: Refugee centers (Ter Apel)

Politics:

Government resigned over asylum seekers

- The Rutte IV government in the Netherlands resigned in July 2023 over a dispute about asylum policy—specifically, proposed restrictions on the reunification of refugee families.

Most central theme in campaign (VVD,NSC)

- Frame on housing, education (dont have to be immigration issues)

PVV as line of conflict

broader lessons from 2023 Dutch case

1. Rise of the cultural line of conflict

2. Rise of radical right

3. Consequences of conflict

- The effects of conflict lines for the center left and center right

- misunderstood role of centrist parties: will lose if you defend the status quo instead of providing alternatives

4. Broad coalitions

- Alternatives at the flanks

- weakening conflict lines in long run with broad coalitions

"Elections and the Electoral System in the Netherlands"

Henk van der Kolk

1. Core Structure of the Electoral System

- The Dutch electoral system is a list-based, proportional representation (PR) system.

- introduced in 1917 to replace a single-member district system and has proven extremely stable over time.

- Seats are distributed nationally, not per district, making the system highly proportional and open to new parties.

2. Open and Inclusive System

- Since 1919 (with women's suffrage), the system has been inclusive, gradually expanding voting rights (e.g., lowering voting age, extending to Dutch citizens abroad).

- Anyone can submit a list, but most are submitted by registered political parties.

3. Electoral Mechanics

- No by-elections: Vacancies are filled from the original party list.

- Electoral districts still exist, but they play a very limited role in vote counting.

- The D’Hondt system is used to allocate seats to parties, slightly favoring larger ones.

- There’s a low electoral threshold (1 full seat), keeping the system open to small parties.

4. Historical Development and Institutional Stability

- Despite several reforms (e.g., introduction of female suffrage, abolition of compulsory voting in 1970), the core features from 1917 remain intact.

- Compulsory voting existed until 1970 but was removed as voting shifted from a civic duty to a personal right.

- Electoral stability is largely maintained because political parties benefit from the status

“Changing Patterns of Party Choice in Dutch Electoral Politics”

Tom Louwerse and Wouter van der Brug

1. Dutchification of Politics

- The Netherlands is a frontrunner in volatility and fragmentation in Europe.

- “Dutchification” refers to:

- Rising electoral volatility

- Fragmentation of the party system

- Decline of traditional parties (CDA, PvdA)

- Rise of niche and populist parties

2. Decline of Traditional Mass Parties

- CDA: Dominant until 1980s; steep decline after 2010.

- PvdA: Strong in 1970s–1990s; collapsed after joining coalition with VVD (2012–2017), losing 75% of voters.

- VVD: Only traditional party to grow or remain stable, aided by decline of CDA.

3. High Electoral Volatility

- Volatility rose from ~6% (1945–1970s) to 20%+ in 2000s.

- Dutch elections now among the most volatile in Europe.

- Shift driven by decline of socio-structural voting and rise of issue-based preferences.

4. Fragmentation and the Rise of Mid-sized Parties

- Effective number of parties rose to 8 by 2021.

Not more splinter parties (<3.5%)—instead, more medium-sized parties (7–20%).

- New populist parties on both left (SP) and right (LPF, PVV, FVD, BBB, NSC).

5. Electoral Costs of Ruling

- Governing parties increasingly lose votes ("cost of ruling").

- Junior partners almost always lose; largest party/PM sometimes benefits (e.g., Rutte in 2012).

6. Explanations for Electoral Change

- Shift from long-term structural factors (class, religion) → to short-term factors (issues, leaders, media).

- Dutch voters now make choices based on issue salience and party proximity, not loyalty.

7. From One-Dimensional to Two-Dimensional Party Space

- Traditionally, Dutch electoral competition was structured largely along a one-dimensional left–right economic axis.

- two-dimensional space better explains modern Dutch party competition:

- economic axis

- cultural axis

elections: lower chamber/House of Representatives

direct elections

- Deceptively easy and straightforward

- Voters choose a candidate from a party list

- Seats are allocated in strict proportion to the total number of votes each party receives

→ Very low threshold (‘Kiesdeler’ = 1 full seat =0.67%)

- Date fixed, but changes with early elections

- One district (but: candidacy)

→ all votes thrown in single group and counted

- De facto: Single party list

Bounded Volatility in the Dutch Electoral Battlefield

Tom van der Meer, Rozemarijn Lubbe, Erika van Elsas, Martin Elff, Wouter van der Brug

1. High but Structured Volatility: Dutch elections are among the most volatile in Europe, but this volatility is bounded, not random.

- Voters mostly shift within ideological blocks

2. Intra-Block Volatility: Voter shifts occur mostly within party blocks, not across them.

- Left: PvdA, SP, GroenLinks (GL)

- Right: VVD, CDA, PVV, TON

- D66 serves as a centrist lynchpin with connections to both sides.

3. Two-Dimensional Party System: The Dutch electoral landscape is best described by:

- socio-economic dimension (left–right, redistribution vs. market)

- sociocultural dimension (multicultural vs. monocultural)

4. Realignment, Not Dealignment: Voter behavior reflects realignment along the sociocultural dimension (e.g., immigration, identity politics) and continued alignment along the socio-economic dimension.

- yet, widening electoral divisions - electoral gap in the traditionally crowded political system

“Fragmented Foes: Affective Polarization in the Multiparty Context of the Netherlands”

Eelco Harteveld

1. Affective Polarization Exists in the Netherlands

- Even in a fragmented, consensus-oriented political system, Dutch citizens exhibit affective polarization—dislike of fellow citizens based on political preferences.

2. Parties vs. Partisans

- Citizens evaluate party supporters ("partisans") differently than the parties themselves.

- While correlated, attitudes toward partisans include a unique emotional dimension that goes beyond political disagreement.

3. Political Divides > Social Divides

- Dislike toward political outgroups is stronger than dislike for non-political outgroups (like religious, ethnic, or regional groups), suggesting politics is a primary social divider.

4. Gradual, Not Block-Based Division

- Instead of clear ingroup-outgroup divisions, dislike increases with ideological distance.

- There's no rigid two-block structure (left vs. right); citizens tend to evaluate others more negatively the further they are ideologically.

5. Cultural Issues Are More Polarizing Than Economic Ones

- Disagreement over cultural issues (e.g., immigration, gender roles) generates greater affective distance than economic issues (like welfare policy).

6. Populist Radical Right (PRR) Exceptionalism

- Voters of PRR parties (like PVV and FvD) both express and receive the most negative affect—more so than ideological distance alone would suggest.

- This "double exceptionalism" amplifies affective polarization.

elections: upper chamber/Senate

indirect elections via Provincial council (Staten)

- provincial council members elect

- weighted based on the population of their province.

→ leads to strategizing - trading votes in different places

- more or less composed of what you'd expect if it were national election

More complicated

- Fixed date: every 4 years

- Single party list for the Senate

- Very low threshold (‘Kiesdeler’)

elections: government, head of state (king), prime minister

not elected

Strong continuity since 1917-1919: changes

Limited changes:

- Threshold has decreased

- Voting age decreased

- Compulsory turnout ended

Strong continuity since 1917-1919: reasons

1. Constitution

- very hard to change system

2. Partisan self-interest

- large parties that have been successful benefit → least likely to want to change it