PHYS10121 - Quantum and Relativity

1/34

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

35 Terms

Relativity: What are the Galilean Transformations? When can they be used?

x=x^{\prime}+vt (or for y or z if velocity has y or z component)

t=t^{\prime}

These are trivial from diagrams/suvat equations and can be used to prove that Newton’s first law holds in all inertial frames of reference (i.e by showing object moving parallel to y axis in S’ also moves in a straight line in S).

However, (as we can see) it assumes there is universal time i.e time is unchanged between different reference frames. It also suggests that the length of an object will be the same in all frames (as if there are two positions at each end of rod, x1 and x2, we can see from equations x2 - x1 = x2’ - x1’)

Special relativity shows us that these suggestions are not true. therefore these transforms can only be used when v « c , which will give answers that will equal the true answers to a ridiculously good accuracy/precision so do a good enough job

Relativity: Einstein’s first postulate and it’s consequences

Einstein was influenced by Maxwell’s equations which predicted the existence of EM waves which travel at speed c, where c=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu0\epsilon0}}

Einstein’s first postulate proposed that identical isolated experiments in different inertial frames deliver identical results.

For example, experiments to do with Newton’s first law of motion (which Galilean transformations “showed” were the same in all frames) and experiments in electricity and magnetism:

F=\frac{q1q2}{4\pi\epsilon0r^2} , B=\frac{\mu0}{2\pi r} (B is magnetic field due to current in wire)

This suggests that, if Newton’s first law of motion gives the same results in all inertial frames, there should be no way to experimentally prove that one object is “universally moving” - we can only declare it as “moving” with reference to another inertial frame.

This also suggests that \mu0 and \epsilon0 would be the same in all inertial frames (as they must be so that experiments in electricity and magnetism are consistent with his first postulate). Therefore, IF Maxwell’s equations are correct, then the speed of light, c, must also be the same in all inertial frames (leading to Einstein’s second postulate…)

Relativity: Einstein’s second postulate and it’s consequences

The speed of light in a vacuum is the same in all inertial frames. (as predicted by his first postulate, assuming Maxwell was correct)

This has some strange consequences - i.e, imagine 2 observers, one in a frame stationary to a light source and one in a frame moving towards the light source at speed v. the observer in the stationary frame measures light approaching the other observer at c + v while the observer in the moving frame measures the speed of light as just c. This leads ideas of time dilation and length contraction, showing that time is not actually universally constant!

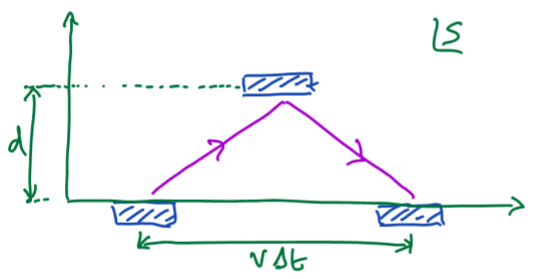

Relativity: Time dilation - light clock thought experiment

Imagine light moving between two mirrors of separation d, set up in frame S’. the time for one ‘tick’ is given by \Delta t^{\prime}=\frac{2d}{c}

Now imagine another frame, S, in which S’ has a constant velocity, v (see diagram). In S, the time for one ‘tick’ will be \Delta t, which we can see is given by \Delta t=\frac{2\sqrt{\left(\frac12v\Delta t\right)^2+d^2}}{c} (bit in sqrt is total distance back and forth between mirrors using pythagoras). note: we have used Einstein’s second postulate here by assuming speed of light is same in all frames.

This can be rearranged to give \Delta t=\frac{2d}{c}\cdot\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}\Delta t^{\prime}

Therefore, we can see

\Delta t=\gamma\Delta t^{\prime} , where \gamma=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c2}}}

Time is NOT the same in all inertial frames! (it just seems to be when v « c as gamma becomes very very close to 1). This is also the same for all clocks (not just light clocks) - note that if it wasn’t and clocks in different frames drifted out of sync, we would be able to tell they were moving, which violates Einstein’s first postulate.

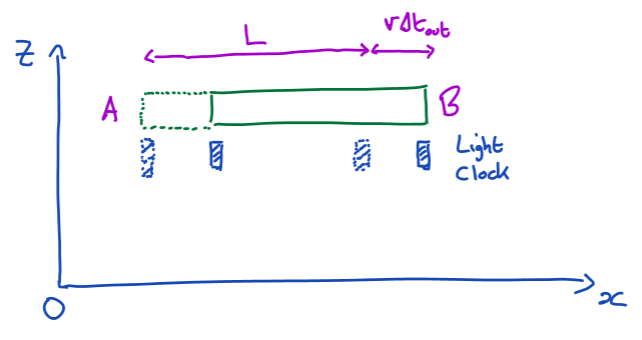

Relativity: Length contraction - ruler and clock thought experiment

Consider a ruler of length L’ as measured in it’s frame, S’. Now imagine S’ is moving with a constant speed (in the x-axis) of v relative to another frame, S. What would the length be according to an observer in frame S (L)?

We can use a light clock to measure the length of the ruler. The time dilation formula can therefore be used to express L in terms of gamma and L’

Position one mirror (of the light clock) at one end of the ruler and position the other mirror at the other end (see diagram).

IN S FRAME: On the outbound journey (of the light ray), we see the distance traveled is equal to c\Delta tout=L+v\Delta tout. On the return journey, the distance traveled will be c\Delta tback=L-v\Delta tback. this gives a total time (in S frame) of \Delta t^{}=\frac{L}{c-v}+\frac{L}{c+v}

IN S’ FRAME: There is no relative motion between the ruler and the reference frame, so outbound and return time is the same and the total time in this frame can simply be found with suvat: \Delta t^{\prime}=\frac{2L^{\prime}}{c}

Using the formula for time dilation (\Delta t=\gamma\Delta t^{\prime}) we can see

\frac{L}{c-v}+\frac{L}{c+v}=\frac{\gamma2L^{\prime}}{c}

L=\frac{L^{\prime}}{\gamma} , where \gamma=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c2}}}

Length is NOT the same in all inertial frames!! Objects that are moving relative to a frame appear smaller in that frame than they appear in their rest frame (frame where they have no relative motion).

Relativity: Muons as an example of both time dilation and length contraction

When measured on Earth (so the muon is at rest in Earth’s reference frame), muons have a half-life of just 2.2 microseconds. They are created in cosmic ray collisions ~20 km above Earth’s surface, yet can be detected by detectors on the ground, suggesting they are traveling faster than the speed of light!?

Explanation with time dilation: The created muons move very close to the speed of light, let’s say with v = 0.9999c. From Earth’s frame, the muons are time dilated, so their half life (according to earth) is longer than the 2.2 microseconds measured in muons on Earth (= 2.2 microseconds * gamma), explaining why (according to earth) they can travel 20km while not moving faster than the speed of light.

Explanation with length contraction: from the muon’s frame, the Earth is moving towards them at 0.9999c, so the atmosphere has been length contracted by a huge amount (= 1/gamma) allowing them to travel through all of it in (according to them) just 2.2 microseconds.

This shows us that time dilation and length contraction are basically just different ways of showing the same thing (and that they are both needed as if only one existed without the other to explain phenomena from the other observer’s point of view, it would literally break every law of physics ever and cause lots of confusion and mess.)

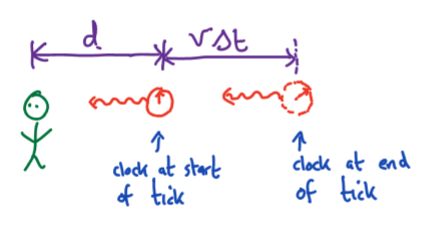

Relativity: Doppler effect for light - time interval between clock ticks for observer moving relative to clock

Let observer be in S frame, clock in S’ frame which is moving with speed v (x-axis) relative to S. Time interval between ticks for observer = \Delta T .

At start of tick, clock at distance d from observer. at end of tick, clock at distance v\Delta t from observer (see diagram). Note the time that has passed does NOT equal the time interval.

Assume the light from the start of the tick arrives at the observer at t = 0. The light emitted at end of tick therefore arrives \frac{v\Delta t}{c}+\Delta t later. Therefore:

\Delta T=\Delta t\left(1+\frac{v}{c}\right)=\gamma\Delta t^{\prime}\left(1+\frac{v}{c}\right) (due to time dilation equation)

\Delta T=\frac{1+\frac{v}{c}}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}\Delta t^{\prime}=\sqrt{\frac{1+\frac{v}{c}}{1-\frac{v}{c}}}\Delta t^{\prime}

We can use this to get an expression for the doppler effect including relativistic effects: T=\frac{1}{f}, therefore for S, T=\Delta T and for S’, T=\Delta t^{\prime}

Therefore:

\frac{1}{f}=\sqrt{\frac{1+\frac{v}{c}}{1-\frac{v}{c}}}\cdot\frac{1}{f^{\prime}} (f is frequency in S, f’ in S’)

f=\left(\frac{1-\frac{v}{c}}{1+\frac{v}{c}}\right)^{\frac12}f^{\prime}

Using f=\frac{c}{\lambda} (which is usable in all inertial frames as c is constant) can be used to find the doppler shift in wavelength for light emitters moving at relativistic speeds towards/away from observers.

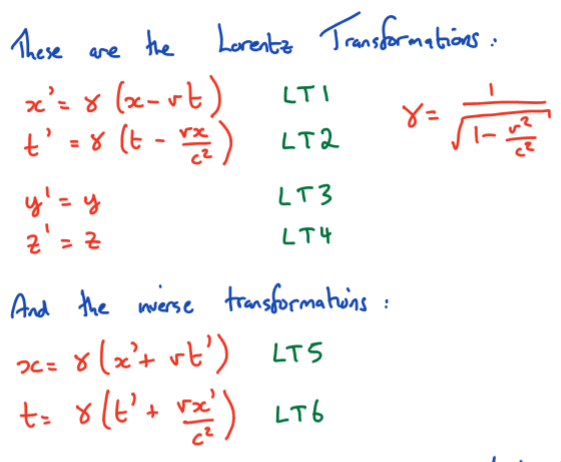

Relativity: Lorentz transformations:

Lorentz transforms are equations that relate the coordinates of an event in one inertial frame to the coordinates of the same event in a second inertial frame (i.e Galilean transforms but actually account for relativity)

Assuming velocity in x direction:

x^{\prime}=\gamma\left(x-vt\right) (LT1)

t^{\prime}=\gamma\left(t-\frac{vx}{c^2}\right) (LT2)

y^{\prime}=y (LT3)

z^{\prime}=z (LT4)

Reverse transforms:

x^{}=\gamma\left(x^{\prime}+vt\right) (LT5)

t^{}=\gamma\left(t^{\prime}+\frac{vx^{\prime}}{c^2}\right) (LT6)

These can also be used directly for coordinate differences (\Delta x=x2-x1 , \Delta t=t2-t1) by simply subbing in x=\Delta x and t=\Delta t (and vice versa for prime versions)

Relativity: Deriving Lorentz transforms

We can assume position in one frame will be related to position AND time in the other. Same assumption for time. We then assume that the transformations are linear, i.e is the same everywhere (true for special relativity… but not general!) Therefore in simplest terms,

x^{\prime}=ax+bt (1)

t^{\prime}=dx+et (2)

We now find coefficients a, b, d, and e (note we didn’t use c as this denotes speed of light):

State that origin O’ (where x’ = 0) moves along x axis with speed v where x = vt. Sub into (1):

0=avt+bt , -\frac{b}{a}=v (3)

Similarly, state O (x = 0) moves along x’ axis at speed -v (duh) where x’ = -vt’. Sub into (1):

x^{\prime}=bt

t^{\prime}=et

-\frac{b}{e}=v (4)

Combining (3) and (4) gives e = a , b = -av. Sub into (1) and (2):

x^{\prime}=ax-avt , t^{\prime}=dx+at (5)

Note here that if t = t’, we recover the Galilean transformations! (as d = 0, e = a = 1)

We now use Einstein’s second postulate to eliminate x / x’: c is same in all inertial frames - Consider a photon emitted at O and O’ when they are coincident, i.e when t’ = t = 0. Photon travels along the x and x’ axis so that x = ct, x’ = ct’. Sub into equations (5):

ct^{\prime}=act-avt , t^{\prime}=dct+at

d=-\frac{av}{c^2}

From combining this with (1) and (2), we are now left with:

x^{\prime}=a\left(x^{}-vt^{}\right) , t^{\prime}=a\left(t-\frac{vx}{c^2}\right) (6)

Note that equations (6) must take same forms in all inertial frames so we can simply swap the primed and unprimed coordinates and swap the sign of v to find the same equations just reversed:

x^{}=a\left(x^{^{\prime}}+vt^{^{\prime}}\right) , t^{}=a\left(t^{\prime}+\frac{vx^{\prime}}{c^2}\right) (7)

To solve for a, we substitute x’ and t’ from (6) into equations (7):

x=a\left(ax-avt+avt-\frac{av^2x}{c^2}\right)=a^2x\left(1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}\right)

cancel for x and rearrange:

a=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}=\gamma !!!!!!!!!

Now we have all unknowns, giving us our Lorentz transforms!

Relativity: When deriving Lorentz transformations, why do we assume they are linear transformations?

1) Spacetime is same everywhere (under Special relativity): we could choose origin of coordinate system to be anywhere and the equations will have the same forms

2) Newton’s first law: We proved N1 is valid in all inertial frames under Galilean transforms so we assume the same will be true for Lorentz transforms

3) (best reason kinda) Einstein’s first postulate: We could say Lorentz transforms must be linear so that Einstein’s first postulate, that laws of physics are same in all inertial frames, is true, as if they were not linear, N1 would not be the same in all inertial frames so would break Einstein’s first postulate

tl;dr, Einstein’s first postulate states N1 must be true in all frames, N1 is true because spacetime is same everywhere, therefore Lorentz transforms must be linear so that spacetime is the same everywhere.

Relativity: Deriving time dilation with Lorentz transforms

consider clock at rest in S’ at position x0’. One tick of clock starts at t1’ and ends at t2’, giving \Delta t^{\prime}=t2^{\prime}-t1^{\prime}. How long is this tick in S? (\Delta t)

We have two events: start of tick, end of tick. We can use LT6 (t^{}=\gamma\left(t^{\prime}+\frac{vx^{\prime}}{c^2}\right)) to transform these events in S’ into S.

Event 1: (x0’, t1’) in S’, in S, t1^{}=\gamma\left(t1^{\prime}+\frac{vx0^{\prime}}{c^2}\right)

Event 2: (x0’ , t2’) in S’, in S, t2=\gamma\left(t2^{\prime}+\frac{vx0^{\prime}}{c^2}\right)

\Delta t=t2-t1=\gamma\left(t2^{\prime}-t1^{\prime}+\frac{vx0^{\prime}}{c^2}-\frac{vx0^{\prime}}{c^2}\right)

\Delta t=\gamma\Delta t^{\prime}

Relativity: Deriving length contraction with Lorentz transforms

Consider ruler in S’ with one end at x1’ and other at x2’, \Delta x^{\prime}=x2^{\prime}-x1^{\prime}. What is length in S? (\Delta x)

We have two events: Measurement of one end (of ruler), measurement of other end. Both events occur at the same time in S (= t0) by definition; we want length of ruler measured by one observer at rest in S.

We can use either LT1 or LT5 - LT5 directly transforms x’ into x, but using LT1 actually looks neater due to how the length contraction formula looks in the end*:

Coordinate (/event) 1: x1^{\prime}=\gamma\left(x1-vt0\right)

Coordinate (/event) 2: x2^{\prime}=\gamma\left(x2-vt0\right)

\Delta x^{\prime}=x2^{\prime}-x1^{\prime}=\gamma\left(x2-x1+vt0-vt0\right)

\Delta x^{\prime}=\gamma\Delta x,

\Delta x=\frac{\Delta x^{\prime}}{\gamma} *

Relativity: Velocity transformations

Consider an object moving with velocity v’ (vector with both vx’ and vy’ components) in S’. An observer in S sees the S’ reference frame moving away from them with speed u (purely in x direction). What is the velocity, v, of the object in the S frame?

We want 2 equations: one for vx, and one for vy. We can do this using Lorentz transforms as:

vx=\frac{dx}{dt} and vy=\frac{dy}{dt}

Just like we subbed in \Delta x=x and \Delta t=t into Lorentz transforms before, we can do the same with dx and dt.

Using LT5 and LT6:

For vx: vx=\frac{\gamma\left(dx^{\prime}+udt^{\prime}\right)}{\gamma\left(dt^{\prime}+\frac{udx^{\prime}}{c^2}\right)}=\frac{\left(\frac{dx^{\prime}}{dt^{\prime}}+u\right)}{\left(1+\frac{u}{c^2}\frac{dx^{\prime}}{dt^{\prime}}\right)} , vx^{\prime}=\frac{dx^{\prime}}{dt^{\prime}}

vx=\frac{vx^{\prime}+u}{1+\frac{uvx^{\prime}}{c^2}}

For vy: vy=\frac{dy^{\prime}}{\gamma\left(dt^{\prime}+\frac{udx^{\prime}}{c^2}\right)}=\frac{\frac{dy^{\prime}}{dt^{\prime}}}{\gamma\left(1+\frac{u}{c^2}\frac{dx^{\prime}}{dt^{\prime}}\right)}

vy=\frac{vy^{\prime}}{\gamma\left(1+\frac{uvx^{\prime}}{c^2}\right)}

Note: be careful with sign of u, and also remember u = relative speed of S’ as observed in S, NOT speed of object (that is v duh)

Relativity: 4D position vectors of Spacetime

Spacetime is 4-dimensional: 3 direction dimensions and 1 time dimension. This gives us the equation for a position vector in spacetime:

X=\left(ct,x,y,z\right)

Note: c is included so that all dimensions have the same units. We can do this as c is invariant in spacetime so is the same always.

Relativity: The Spacetime interval - What is it?

Defined as \Delta S where \left(\Delta S\right)^2=c^2\left(\Delta t\right)^2-\left(\Delta x\right)^2 and \left(\Delta S\right)^2=\left(\Delta S^{\prime}\right)^2.

This last bit can be easily proven using Lorentz transforms and shows that it is invariant, i.e it is the same in ALL inertial frames, like the speed of light!

The first bit is very interesting as it looks a lot like pythagoras but with a -ve? What does this suggest about \Delta S? To find out, we look at vectors of spacetime:

Consider 2 events:

Event 1: X1 =\left(ct1,x1\right)

Event 2: X2 =\left(ct2,x2\right)

(note that these events have y and z = 0, hence why they are not included)

Plot these events on the same spacetime diagram in the same inertial frame (see diagram). We can see:

\Delta X=X2-X1=\left(c\left(t2-t1\right),\left(x2-x1\right)\right)=\left(c\Delta t,\Delta x\right)

We know from maths that the length of a vector can be found by the dot product of itself square rooted (in 3D, this is just pythag! however, in 4D dot product works a bit differently..)

Remembering that \left(\Delta S\right)^2=\left(c\Delta t\right)^2-\left(\Delta x\right)^2 , let’s define the dot product in 4D as the same in 3D, but with a minus sign instead of a plus sign (just cause why not).

This gives us:

\Delta X\cdot\Delta X=\left(c\Delta t\right)^2-\left(\Delta x\right)^2=\left(\Delta S\right)^2

This suggests that \Delta S is the length in 4D spacetime of \Delta X, referred to as the interval between two events in spacetime (Event 1 and Event 2 in this case). The fact that \Delta S is invariant means that the interval (between two events in 4D spacetime) is the same in ALL inertial frames!! Obviously, Lorentz transforms show us that \Delta x and \Delta t do not equal \Delta x^{\prime} and \Delta t^{\prime}, but the interval (between these two events) does not change, no matter what reference frame you are observing it from!!!!!!!!

Relativity: Deriving time dilation using the spacetime interval (\Delta S)

Imagine clock stationary in S’, S’ is moving with speed u relative to S.

In S’, the spacetime interval between ticks of clock is \left(\Delta S^{\prime}\right)^2=\left(c\Delta t^{\prime}\right)^2-0 (as clock is stationary so \Delta x^{\prime}=0)

In S, the spacetime interval is \left(\Delta S\right)^2=\left(c\Delta t\right)^2-\left(\Delta x\right)^2 and \Delta x=u\Delta t

Spacetime interval is invariant, \left(\Delta S\right)^2=\left(\Delta S^{\prime}\right)^2, therefore:

\left(c\Delta t^{\prime}\right)^2=\left(c\Delta t\right)^2-\left(u\Delta t\right)^2

\Delta t^{\prime}=\sqrt{1-\frac{u^2}{c^2}}\Delta t

\Delta t=\gamma\Delta t^{\prime} (where \gamma=\sqrt{\frac{1}{1-\frac{u^2}{c^2}}} as per usual)

Relativity: The Twins Paradox

Imagine one twin travels out into space (event 1) at a steady speed v, before turning around (event 2) and returning home at the same speed (event 3). Each leg of the journey takes 2 minutes. How long does the journey take according to the other twin at home, and hence, which twin ages more?

Step 1: Calculate total interval between event 1 (leaving) and event 3 (returning back home) in frame of the home twin (\Delta S):

From E1 to E2:

\Delta S_1^2=\left(\frac{c\Delta t}{2}\right)^2-\left(\Delta x\right)^2

From E2 to E3:

\Delta S_2^2=\left(\frac{c\Delta t}{2}\right)^2-\left(\Delta x\right)^2

where Delta t is the total time between E1 and E3, and Delta x is the distance travelled for each leg, i.e \Delta x=\frac{v\Delta t}{2}

Therefore total interval given by:

\Delta S=\Delta S_1+\Delta S_2=2\sqrt{\left(\frac{c\Delta t}{2}\right)^2-\left(\frac{v\Delta t}{2}\right)^2}=c\Delta t\left(1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}\right)^{\frac12} i.e \Delta S=\frac{c\Delta t}{\gamma}

Step 2: Calculate total interval between E1 and E3 in frame of moving twin (\Delta S^{\prime}):

Moving twin is stationary in their reference frame, so \Delta x=0, hence

\left(\Delta S^{\prime}\right)^2=\left(c\Delta t^{\prime}\right)^2

\Delta S^{\prime}=c\Delta t^{\prime}

Step 3: Use invariance of spacetime interval:

\Delta S=\Delta S^{\prime}

\frac{c\Delta t}{\gamma}=c\Delta t^{\prime}

hence, as 1/gamma is always < 1, \Delta t>\Delta t^{\prime}

More time has passed for twin at home - twin at home aged more

Relativity: Momentum - Defining momentum (both 4-vector and 3-vector spacial) in spacetime

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum is

p=m\frac{dx}{dt} (p and x are 3D vectors)

so we might expect that in spacetime,

P=m\frac{dX}{dt} (P and X are 4D vectors)

However, this doesn’t work as dt is not invariant - it depends on choice of reference frame (\Delta t=\gamma\Delta t^{\prime})

We therefore define a new variable using the invariants we do have - the proper time \tau, defined as

d\tau=\frac{dS}{c}

Momentum in terms of proper time (note x in 4-vectors X and S is a 3D vector containing all directions of space, i.e x = (x,y,z)):

P=m\frac{dX}{d\tau}=\frac{m\left(cdt,dx\right)}{\frac{1}{c}\sqrt{\left(cdt\right)^2-\left(dx\right)^2}}

P=\frac{m\left(cdt,dx\right)}{dt\sqrt{1-\frac{1}{c^2}\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right)^2}}

Note that \frac{dx}{dt}=v = velocity in S (in 3D vector (x,y,z) i.e this is a vector)

Therefore:

P=m\gamma\left(\frac{cdt}{dt},\frac{dx}{dv}\right)

P=m\gamma\left(c,v\right) (remember v is velcoity vector)

Can also be written as P=mV where V is the 4-velocity, V=\frac{dX}{d\tau}

Note that if we take v « c, i.e gamma = 1, this reduces to P = (mc, mv) - the second part reduces to the usual spatial 3-momentum in non-relativistic limits! Therefore we conclude that \gamma mv equals the spacial momentum vector, p.

Relativity: Momentum - Defining energy in spacetime

Recall momentum in spacetime: P=m\gamma\left(c,v\right). the second term is the spacial momentum, what is the first term!?

first term = \gamma mc=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}mc

Assumign non-relativistic, i.e v « c allows us to binomially expand \left(1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}\right)^{-\frac12} which gives:

1+\frac{v^2}{2c}+\cdots

Therefore m\gamma c=mc+\frac{mv^2}{2c}+\cdots

multiply both by c…

\gamma mc^2=mc_{}^2+\frac12mv^2+\cdots

Second term is newtonian expression for kinetic energy! Therefore we assume \gamma mc^2 is linked to energy:

\frac{E}{c}=\gamma mc

E=\gamma mc^2

(used when gamma is not close to 1, i.e v is close to c)

Can also be written as;

E=K+mc^2.

K is the kinetic energy and mc² is the ‘rest mass energy’. Means kinetic energy can be found from

K=\left(\gamma-1\right)mc^2

In the non relativistic frame this is more obvious:

E=mc^2+\frac12mv^2

(we use this expression when gamma ~= 1, i.e v « c)

‘rest mass energy’ shows us mass can be created and destroyed as long as it is made up for by a change in associated kinetic energy.

Relativity: 4-vector Momentum defined in terms of energy and (3-vector) spacial momentum

Recall definition of 4-vector momentum, P=m\gamma\left(c,v\right)

we found that spatial momentum vector is given by p=\gamma mv and the total energy (NOT vector) is given by E=\gamma mc^2

Therefore, we can write P as:

P=\left(\frac{E}{c},p\right)

most commonly used form, just remember what E and p mean!

Relativity: Conservation of momentum and energy in 4-vector spacetime

Recall 4D momentum being given as:

P=m\gamma\left(c,v\right)=\left(\frac{E}{c},p\right)

In a given inertial frame, both E (energy) and p (spacial momentum) are conserved - if working in one inertial frame, 4-vector P (and therefore it’s components E and p) is conserved (useful for calculations)

However, if we calculate them in one frame, they will have different values in another, hence they are NOT invariant! (and therefore neither is P).

This similar to what we saw with X. However, the ‘length’ of X (\Delta S) turned out to be invariant…

Relativity: The Invariant Mass

X (4-vector of position in spacetime) is not invariant, but X.X (\Delta S, the spacetime interval) is. Recall P, the 4-vector of momentum in spacetime:

P=m\frac{dX}{dt}=\left(\frac{E}{c},p\right)

On it’s own, this is also not invariant. is the ‘length’ of P also invariant, like the ‘length’ of X is?

It turns out the answer is yes, and it is known as the invariant mass:

P\cdot P = invariant mass * c²

(i.e invariant mass = \frac{P\cdot P}{c^2}), where invariant mass is defined as m²

Using definition of P, we see

P\cdot P=\left(\frac{E}{c}\right)^2-p\cdot p

(remember dot product is -ve with 4-vectors!) so can also be written as:

\left(\frac{E}{c}\right)^2-p\cdot p=m^2c^2

This also applies for systems of many particles, where we use Ptotal:

P_{tot}=\left(\frac{E_{tot}}{c},p_{tot}\right)

P_{tot}\cdot P_{tot}=\frac{E_{tot}^2}{c^2}-p_{tot}\cdot p_{tot}=M^2c^2

(M is invariant mass of system)

“proof”:

Imagine a single particle: E=\gamma mc^2 and p=\gamma mv, hence:

P\cdot P=\left(\gamma mc\right)^2-\left(\gamma mv\right)^2

P\cdot P=\gamma^2m^2c^2\left(1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}\right)

P\cdot P=m^2c^2

(shows why invariant mass = \frac{P\cdot P}{c^2})

Relativity: Using invariant mass to find the relativistic equation for energy in terms of mass and momentum

Recall invariant mass shows we can write

P\cdot P=\left(\frac{E}{c}\right)^2-p\cdot p

and

P\cdot P=m^2c^2

Equating both these definitons allows us to find an equation of energy:

\frac{E^2}{c^2}-p^2=m^2c^2

E^2=c^2p^2+m^2c^4

(note we have written p\cdot p=p^2 here just to make it clearer what we are doing)

This can be used for relativistic calculations when invariant mass is used and does NOT include gamma, making it simpler than trying to use E=\gamma mc^2

Relativity: Energy and momentum of particles when v = c

Recall momentum 4-vector: P=\left(\frac{E}{c},p\right), where:

E=\gamma mc^2

p=\gamma mv

This shows us we can express E as:

E=\frac{c^2p}{v}

when v = c,

E=cp

Alternatively, recall E^2=c^2p^2+m^2c^4, the other way of writing the relativistic equation for energy.

Particles travelling at v = c have m = 0, hence equation simplifies to

E=cp

Rearranging shows their momentum is given by p=\frac{E}{c}, hence their momentum 4-vector would be:

P=\left(\frac{E}{c},\frac{E}{c}\right) ,

where the second term (momentum) has x, y, and z components (as remember, momentum is a vector)

Wait, how do massless particles have momentum!?

We know that particles travelling at v = c MUST be massless. Given p=\gamma mv, this seems to suggest both p (and also therefore E) must be 0, yet this is not true! (photons carry energy as can be quite literally seen as light)

massless particles have momentum because when v = c, gamma = infinity, so \gamma m is not easily defined - this definition of momentum does not hold when v = c! (just when v is close to c)

Relativity: Usefullness of ‘zero-momentum frames’ (pion production example)

Remember that in an inertial frame, P is conserved, but P is NOT the same in all inertial frames. This can often be useful! i.e, questions are often a lot easier to solve in a frame where the total momentum (p component of P) is zero:

When photons scatter off protons, they produce neutral pions (the proton stays, i.e before there is a photon and proton, after there is a pion and proton)

Imagine a photon fired at a stationary proton. Find the min energy required to produce a pion (i.e NO photon left after collision, it is all converted into pion).

E must be greater than mpionc² in order to conserve momentum - in this frame, there is momentum

Moving to a different frame where before and after the collision there is NO momentum makes it much easier to solve this question:

In ZM, Etotal now = mpion + mproton (after collision, but remember in inertial frames E is conserved so also equals before collision) and ptotal now = 0

therefore, in ZMF,

M_{inv}=\frac{P\cdot P}{c^2}=\left(m_{\pi}+m_{proton}\right)^2Now we go back to the original frame: Invariant mass must be the same!

In original frame, before the collision:

P_{\gamma}=\left(\frac{E}{c^{}},p_{\gamma},0,0\right)=\left(\frac{E}{c},\frac{E}{c},0,0\right)

(remember for massless particles, E = cp)

P_{proton}=\left(m_{proton}c^{},0,0,0\right)

(remember E² = c²p² + m²c4 and proton is stationary in this frame before collision, so p = 0)As invariant mass is.. invariant:

\frac{P_{\gamma}\cdot P_{proton}}{c^2}=\frac{\left(P_{\gamma}+P_{proton}\right)^2}{c^2}=\left(m_{\pi}+m_{proton}\right)^2

Solving this, we can find E, which, as we calculated assuming ALL photon energy creates the pion, i.e no photon after the collision, will be the min energy required.

Quantum: The wave function

The wave function describes the state of a particle and is denoted as

\psi\left(x,t\right)

At every point in space, \psi\left(x,t\right) has a (complex) value known as the amplitude. The modulus square of this amplitude is proportional to the probability to find the particle at that point, i.e \left|\psi\right|^2 is a probability distribution.

Therefore, \left|\psi\left(x,t\right)\right|^2dx is the probability to find a particle at position x to x+dx at time t. Note the modulus signs - rember that \psi\left(x,t\right) gives imaginary answers so when squaring it, we actually want to do \psi^{\ast}\psi

This means this expression must be normalised, i.e:

\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\left|\psi\left(x,t\right)\right|^2dx=1

Normalising the wave function is often the first step in solving many quantum questions, i.e it can be used to find unknowns in your original wave function.

Quantum: Expectation values and standard deviation of wave function

Expectation values are the values of something that we most expect to find, i.e mean values!

When we have any probability distribution, i.e \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}f\left(x\right)dx=1, we can find mean (expected) values of things by multiplying f(x) by them before we integrate, for example the mean value of x would be given by <x>=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}xf\left(x\right)dx.

Remember that \left|\psi\left(x,t\right)\right|^2 is a probability distribution! Therefore finding expected values is as simple as using this method.

i.e, expecation value of…

Position x (i.e mean position):

<x>=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}x\left|\psi\left(x,t\right)\right|^2dx

Position x² (i.e square mean):

<x^2>=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}x^2\left|\psi\left(x,t\right)^{}\right|^2dx

Remember with probability, the standard deviation can be found from

square mean - mean squared

Hence, this can be done here too! For our wave function,

\left(\Delta x\right)^2=<x^2>-<x>^2

Quantum: What is h bar equal to?

\hbar=\frac{h}{2\pi}

Quantum: The momentum operator

p=\frac{h}{\lambda}, so we would therefore like our wave function to take form of a… well, wave.

\psi\left(x\right)=e^{i\frac{2\pi x}{\lambda}}=\cos\left(\frac{2\pi x}{\lambda}\right)+i\sin\left(\frac{2\pi x}{\lambda}\right)

Let’s use the exponential form and sub in the equation written above:

\psi\left(x\right)=e^{i\frac{2\pi px}{h}}=e^{i\frac{p}{\hbar}x}

(remember \hbar=\frac{h}{2\pi} )

2 key things to note:

\left|\psi\left(x\right)\right|^2=e^{i\frac{p}{\hbar}x}\cdot e^{-i\frac{p}{\hbar}x}= constant!!*

\frac{d\psi}{dx}=\frac{ip}{\hbar}e^{i\frac{p}{\hbar}x} , i.e

-i\hbar\frac{d\psi}{dx}=p\psi\left(x\right)

This gives the momentum operator!!

-i\hbar\frac{d}{dx} is the momentum operator, p^.

It ‘extracts’ the momentum from the wave function. For the case where the particle has definite momentum (case we did above*) then <p> = p (-i\hbar\frac{d}{dx}\psi=p\psi)

In general:

<p> =\int\psi^{\ast}\^{p}\psi

Note how p^ is multiplied to the NORMAL wave function, which is then afterwards multiplied by the conjugate wave function. This order IS important, because the function includes d/dx !! (This is also same for all operators in QM - they always ‘operate’ on the second part of the integral)

The operator for finding <p²> is simply p^², i.e -\hbar^2\frac{d^2}{dx^2} . Therefore, we can find the uncertainty in momentum,

\left(\Delta p\right)^2=<p^2>-<p>^2

Quantum: States of definite momentum

States of definite momentum satisfy -i\hbar\frac{d}{dx}\psi=p\psi

Quantum: Heisenburg’s Uncertainty Principle

States that there is a limit on how well we can simultaneously determine the position and momentum of a particle.

Recall \Delta x is the uncertainty in the position of a particle represented by a wave function at a given time, and \Delta p is the uncertainty in the momentum. The principle states:

\Delta x\Delta p\ge\frac{\hbar}{2} (often in questions we use ~ \hbar instead)

Note that for a system of definite momentum (i.e like the one in flashcard for momentum operator), the uncertainty in it’s position is infinite (position cannot be determined)

Quantum: The energy-time uncertainty relation

States \Delta E\Delta t\ge\hbar (often we write as ~ \hbar when doing questions)

Note that time is not an observable thing in quantum mechanics! Instead, Delta t is the timescale for a change in the observable property of a system. If the timescale is short, we are considering a system with a large uncertainty in it’s energy. If it is infinite, the system is in a state of definite energy (known as a stationary state)

Quantum: The Hamiltonian operator

Is the operator for total energy:

recall the momentum operator is -i\hbar\frac{d}{dx}, square momentum operator is -\hbar^2\frac{d^2}{dx^2}

Kinetic energy can be written as p²/2m, and total energy is kinetic energy + potential energy (V).

Therefore we might guess the energy operator is given a similar way. This is true, and gives:

H^ =-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2}{dx^2}+V

Just like the momentum operator for a system of definite momentum, for a particle of definite energy, E:

\left(-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2}{dx^2}+V\right)\psi=E\psi

This operator is used just like every other operator, i.e

<E> = =\int\psi^{\ast}Ĥ\psi

Quantum: States of definite total energy

States of definite total energy satisfy \left(-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2}{dx^2}+V\right)\psi=E\psi

Quantum: The time independent Schrodinger Equation

Is the equation for a particle of definite energy:

\left(-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2}{dx^2}+V\right)\psi=E\psi

To solve for a given potential, V, we need a wave function that satisfies the equation. Think back to the infinite square well - we stated that inside the well, V = 0. We also showed that for a well of length L, \psi\left(x\right)=\sqrt{\frac{2}{L}}\sin\frac{n\pi x}{L} (n is any integer from 1)

Therefore, we can write:

H\psi=-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2}{dx^2}\left(\sqrt{\frac{2}{L}}\sin\frac{n\pi x}{L}\right)

=-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{n^2\pi^2}{L^2}\sqrt{\frac{2}{L}}\sin\frac{n\pi x}{L}=-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{n^2\pi^2}{L^2}\psi

Recall \hbar=\frac{h}{2\pi}, hence this can be written as

H\psi=\frac{n^2h^2}{8mL^2}\psi

H\psi=E\psi where E=\frac{n^2h^2}{8mL^2}

What is this useful for?? - Atom energy levels!!

Imagine we set L to be size of an atom and m to be the mass of an electron - we can find the energy difference between ground state (n = 1) and the first excited state (n = 2), i.e:

E_{n}=\frac{n^2h^2}{8mL^2}

E_2-E_1=\frac{2^2h^2}{8mL^2}-\frac{h^2}{8mL^2}=\frac{h^2}{mL^2}\left(\frac12-\frac18\right) (for this case)