Vision

1/19

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

20 Terms

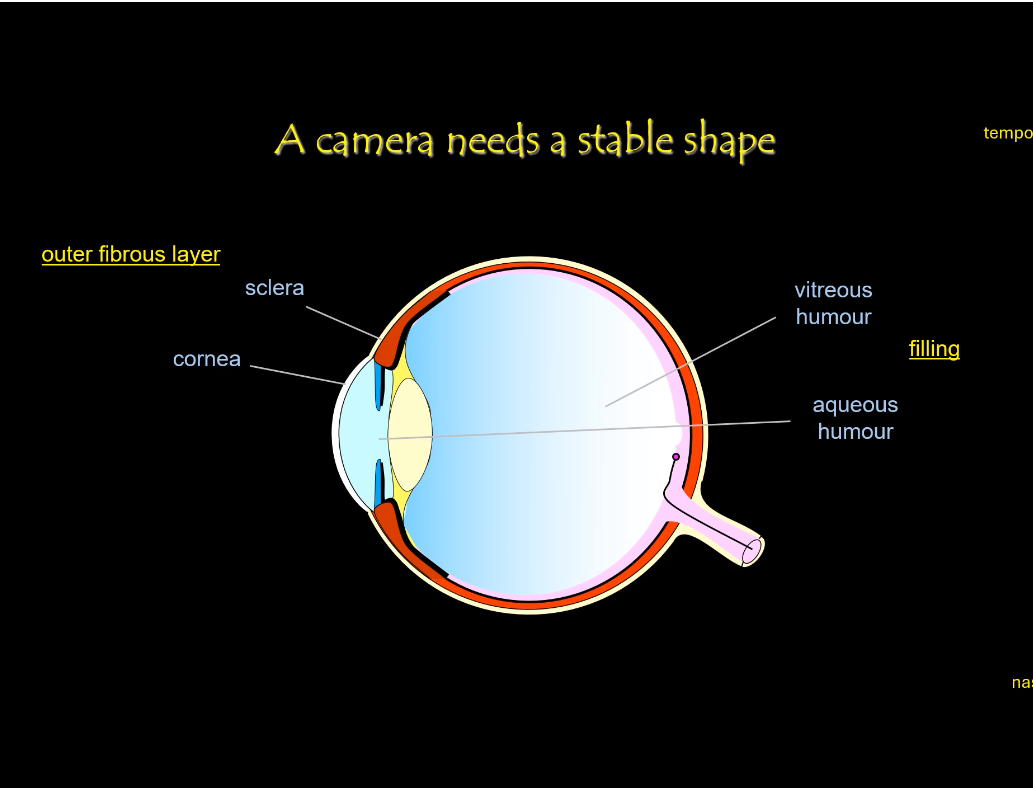

Eye Structure: Stability

The rigid shape of the eye is maintained mainly by:

• Sclera — tough outer coat that protects and maintains globe shape

• Cornea — transparent front surface, also contributes rigidity

• Vitreous humour — gel filling the posterior cavity keeping retina pressed against pigment epithelium

• Intraocular pressure — pressure from aqueous humour maintains the eyeball shape

A stable, round shape is essential so the focal distance stays constant.

The sclera forms a tough outer shell that resists deformation.

This rigidity ensures images remain sharply focused on the retina.

Role of the fluids

Aqueous humour fills the front chamber of the eye.

It maintains internal pressure and nourishes avascular tissues.

Vitreous humour fills the main cavity of the eye.

It supports the retina and preserves the spherical shape.

These ensure a stable optical system for forming images.

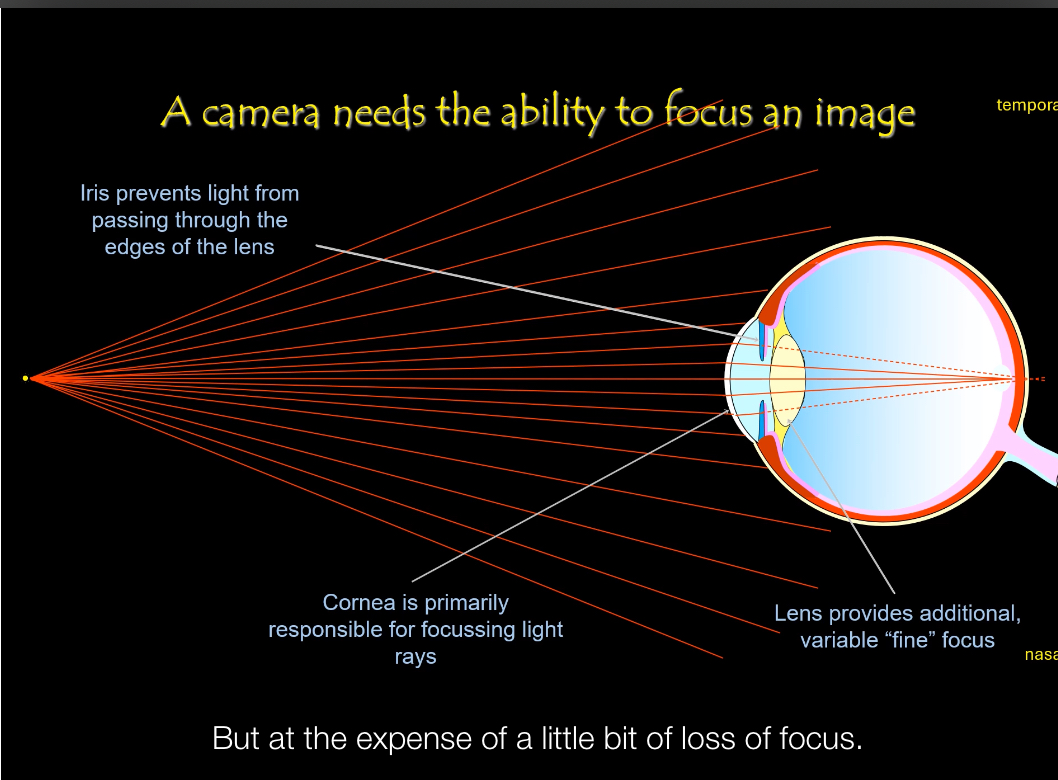

Eye structure: Optical elements

Lens (fine focus)

• Fine-tunes focus after the cornea.

• Changes shape to focus on near vs distant objects (accommodation).

• Acts like the adjustable lens in a camera that sharpens the image.

Ciliary body (focus control mechanism)

• Contains ciliary muscle that controls lens shape.

The ciliary muscle contracts → suspensory ligaments relax → lens becomes rounder → focuses near objects.

The opposite occurs for distant objects.

This dynamic change in shape is called accommodation.

• Contraction reduces tension on the lens, making it rounder for near vision.

• Relaxation increases tension, flattening the lens for distance vision.

• Comparable to the autofocus motor in a camera.

Suspensory ligaments (zonular fibres)

• Attach the lens to the ciliary body.

• Transmit tension changes from the ciliary muscle to the lens.

• Allow the lens to change shape without moving position.

Iris (aperture control)

• Regulates how much light enters the eye.

• Constricts in bright light, dilates in dim light.

• Equivalent to a camera aperture controlling light exposure.

Pupil (light entry point)

• The opening in the iris through which light enters.

• Does not focus light itself but determines light intensity.

• Equivalent to the aperture opening in a camera.

Vitreous humour (optical support & alignment)

• Transparent gel filling the main cavity of the eye.

• Maintains eye shape and keeps the retina in correct position.

• Allows light to pass to the retina with minimal scattering.

• Similar to the internal space of a camera that keeps optics aligned.

Retina (image sensor)

• Detects light at the back of the eye and converts it into electrical signals.

• Receives a focused, inverted image.

• Equivalent to camera film or a digital sensor.

Together they ensure light is sharply focused on the retina.

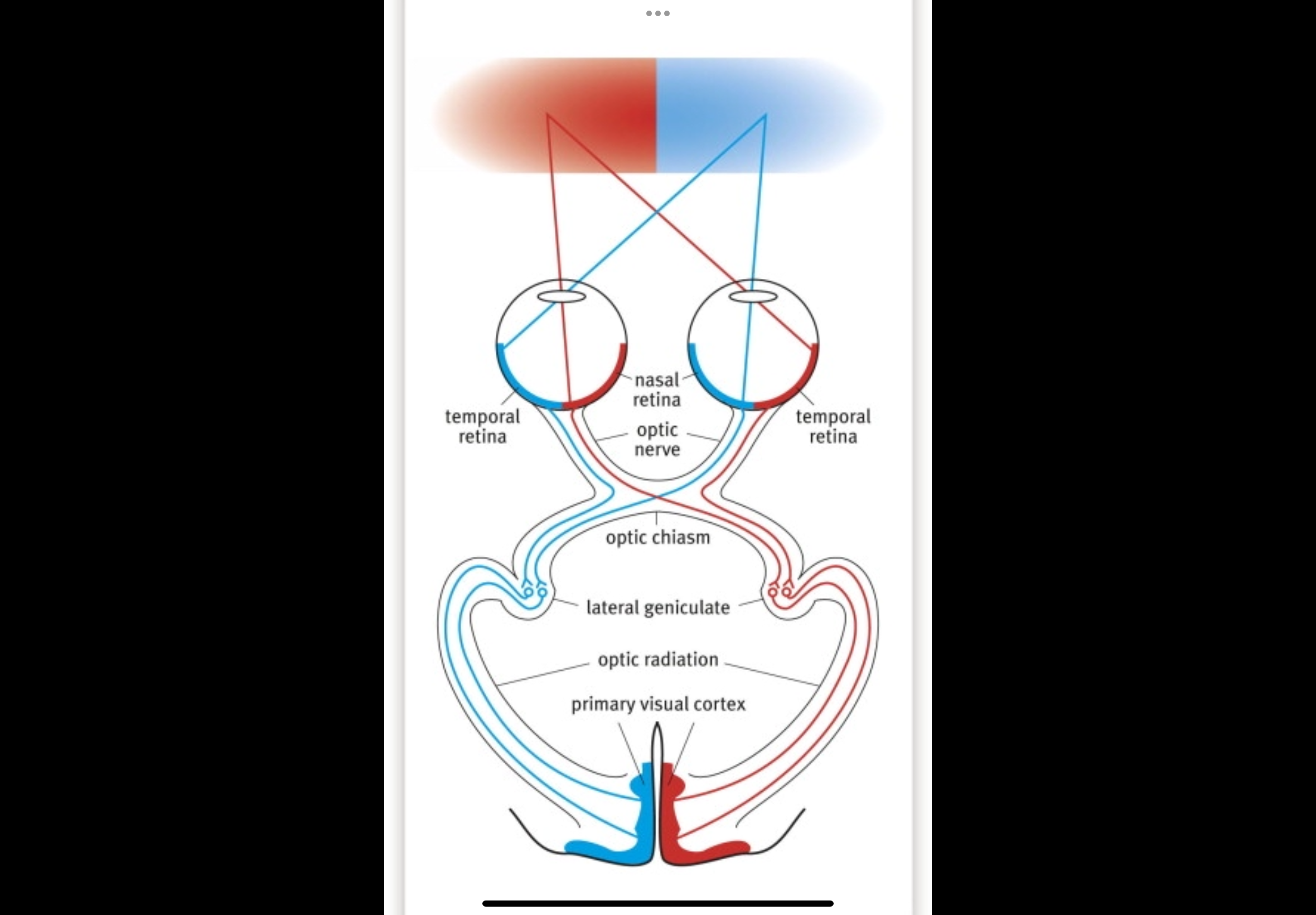

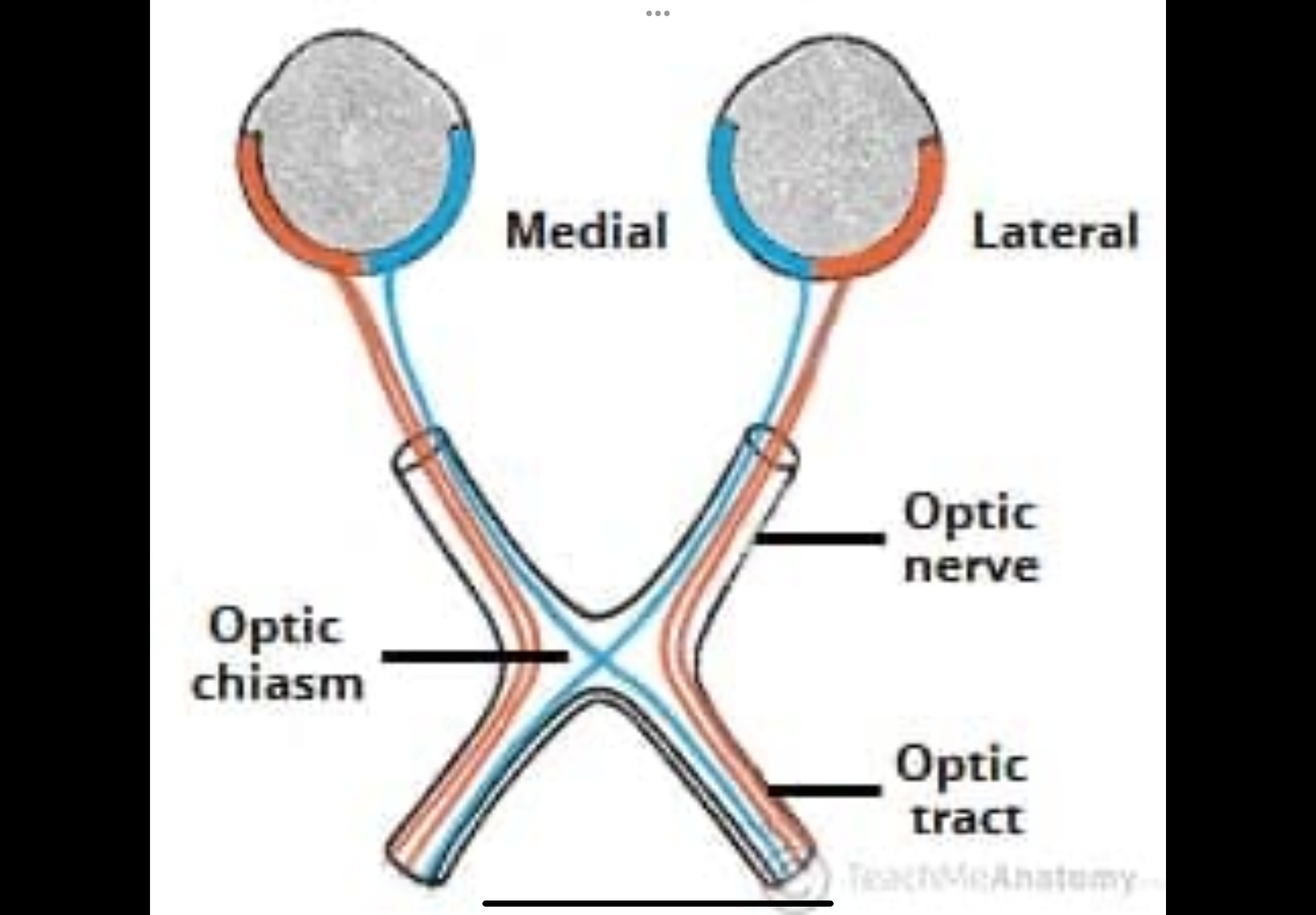

Describe the primary visual pathway

1. Retina

2. Optic nerve

3. Optic chiasm — nasal fibres cross; temporal do not

4. Optic tract

5. Lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN)

6. Optic radiations

7. Primary visual cortex (V1 / area 17)

• Branches to brainstem nuclei controlling eye movements

Retina (signal origin)

Photoreceptors (rods and cones) detect light.

Signals are processed locally by bipolar and ganglion cells.

Ganglion cell axons leave the eye as the optic nerve.

Each retina is divided into:

Nasal retina (medial half)

Temporal retina (lateral half)

Optic nerve

Made of nerve fibres from the retina of one eye.

Carries visual signals from that eye toward the brain.

Contains fibres from both halves of the retina:

Nasal retina fibres

Temporal retina fibres

No fibres have crossed yet at this stage.

Optic chiasm (where crossing happens)

Some nerve fibres physically switch sides here.

Nasal retinal fibres cross to the opposite side of the brain.

Temporal retinal fibres stay on the same side.

This sorting makes sure:

Information from the left side of the world goes to the right brain

Information from the right side of the world goes to the left brain

Optic tract

Forms after the optic chiasm.

Each optic tract now carries information from:

Both eyes

But only one side of the visual field

Right optic tract carries the left visual field.

Left optic tract carries the right visual field.

Fibres now represent both eyes, but only one visual field.

Lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN)

Located in the thalamus.

Major synaptic relay station.

Receives optic tract fibres and organises visual information.

Maintains precise retinotopic mapping.

Modulates signals before sending them to cortex.

Optic radiation

Axons leaving the LGN.

Fan out toward the occipital lobe.

Carry visual information to the cortex.

Upper and lower visual field information travel in different bundles.

Primary visual cortex (V1 / area 17)

Located in the occipital lobe.

First cortical site of visual processing.

Receives a complete, mapped representation of the visual field.

Begins processing of orientation, edges, and spatial detail.

Brainstem branch (non-conscious pathways)

Some optic tract fibres diverge before the LGN.

Project to brainstem nuclei.

Involved in:

Eye movements

Pupillary light reflex

Visual attention and coordination

These pathways do not produce conscious vision.

Retina → optic nerve → optic chiasm (nasal fibres cross) → optic tract → LGN → optic radiation → primary visual cortex, with side branches to brainstem for reflexes.

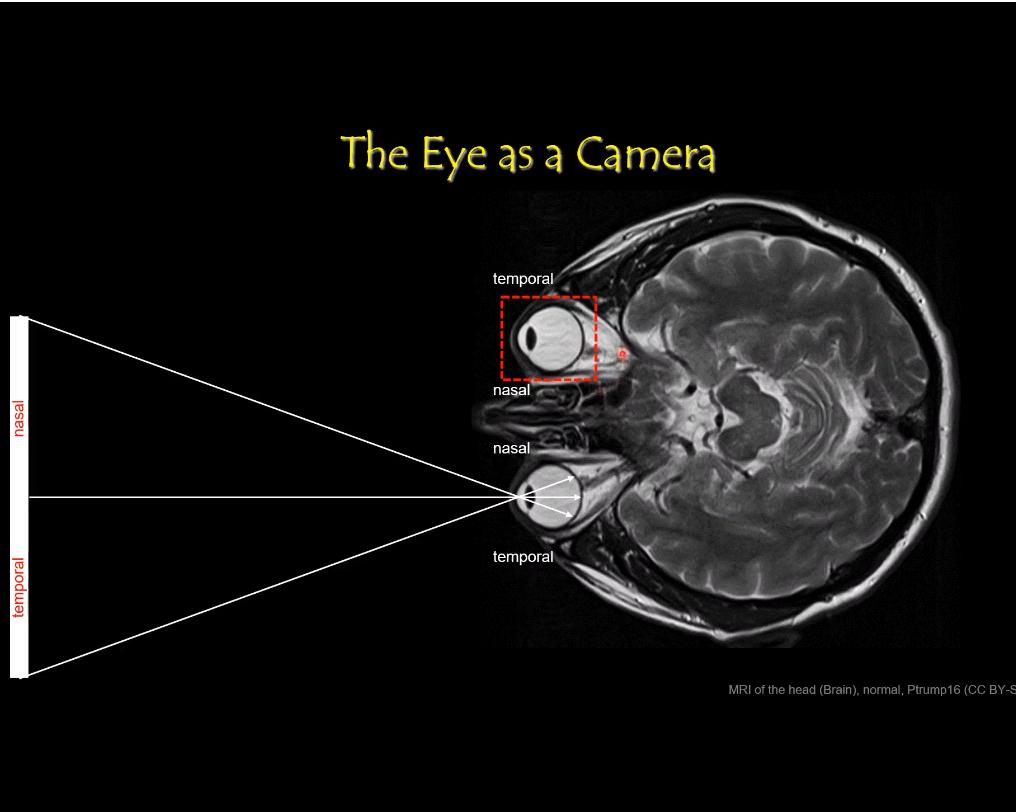

Nasal and Temporal

Visual world = everything you can see in front of you

Split it straight down the middle:

Left visual world = everything left of where you’re looking

Right visual world = everything right of where you’re looking

This has nothing to do with eyes yet. It’s just space.

Second: what “left/right side of the retina” means

Each retina is a curved sheet inside each eye.

For each eye separately:

Nasal retina = side of the retina closer to the nose

Temporal retina = side closer to the temple/ear

So:

Right eye:

Nasal retina = left side of that eye

Temporal retina = right side of that eye

Left eye:

Nasal retina = right side of that eye

Temporal retina = left side of that eye

The ONLY optical rule you need

Images flip on the retina.

So:

Left visual world → right half of each retina

Right visual world → left half of each retina

Now translate that into nasal/temporal.

Left visual world → which retina parts?

Left side of space hits:

Right eye → nasal retina

Left eye → temporal retina

So:

Left visual world = nasal retina (right eye) + temporal retina (left eye)

Right visual world → which retina parts?

Right side of space hits:

Left eye → nasal retina

Right eye → temporal retina

So:

Right visual world = nasal retina (left eye) + temporal retina (right eye)

Why nasal fibres cross (this is the “why”)

The brain wants all left visual world information together

And all right visual world information together

So at the optic chiasm:

Nasal retinal fibres cross

Temporal retinal fibres stay

This brings:

Left visual world → right brain

Right visual world → left brain

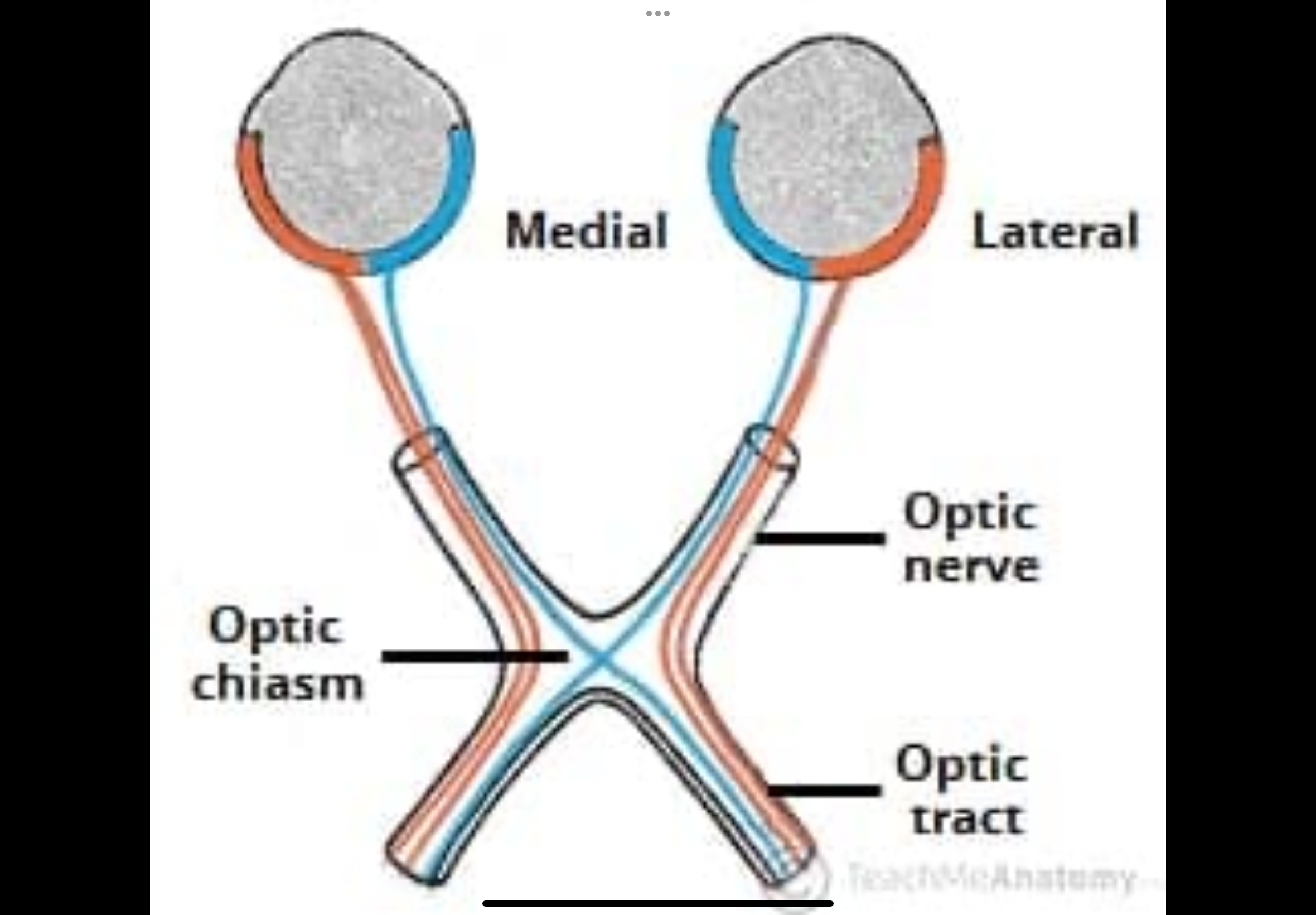

Structure of Photoreceptors (Rods and Cones)

Structure of a photoreceptor (rod or cone)

Overall organisation

Photoreceptors are elongated cells specialised for light detection.

They are divided into distinct regions, each with a specific role in phototransduction and signalling.

Outer segment

Contains stacks of membrane discs.

Discs are packed with photopigment (rhodopsin in rods, opsins in cones).

This is where light is absorbed.

Site of the phototransduction cascade.

Inner segment

Contains mitochondria, ribosomes, and the nucleus.

Provides energy (ATP) and synthesises proteins needed for the outer segment.

Maintains ionic gradients.

Cell body

Contains the nucleus.

Connects metabolic activity to signal transmission.

Axon (connecting fibre)

Thin extension leading toward the synaptic terminal.

Conducts graded electrical changes (not action potentials).

Synaptic terminal

Releases glutamate onto bipolar cells.

Uses graded neurotransmitter release rather than spikes.

Amount of glutamate released depends on membrane potential.

Resting Membrane Potential of Photoreceptors: Dark

Resting membrane potential of a photoreceptor (in the dark)

Key idea

Photoreceptors are unusual because they are depolarised in the dark, not at rest like most neurons.

What sets the resting potential

In darkness, intracellular cGMP levels are high.

cGMP keeps cation channels open in the outer segment membrane.

Sodium (and some calcium) continuously enters the cell.

This inward current is called the dark current.

Ion movements

Na⁺ enters at the outer segment.

K⁺ exits from the inner segment.

The balance of Na⁺ influx and K⁺ efflux keeps the cell depolarised.

Membrane potential

Resting (dark) membrane potential is about –40 mV.

This is much less negative than typical neurons (≈ –70 mV).

Neurotransmitter release

Because the cell is depolarised:

Voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels at the synaptic terminal stay open.

Glutamate is continuously released onto bipolar cells.

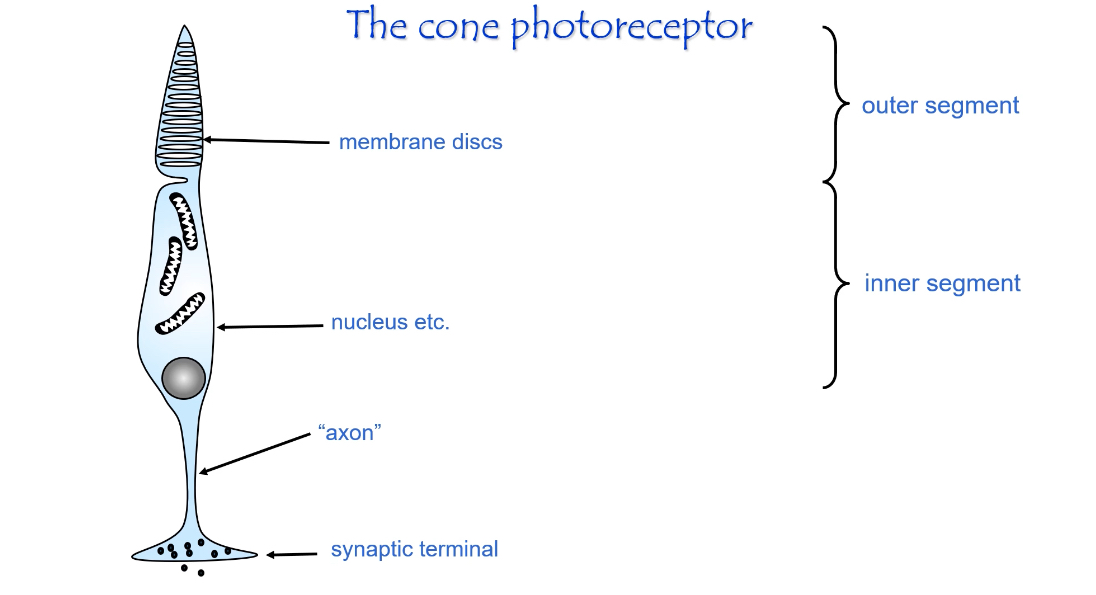

Light and Photoreceptors

Starting state (just before light)

cGMP levels are high.

cGMP-gated Na⁺ channels are open.

Na⁺ enters the outer segment (dark current).

The cell is depolarised and releasing glutamate.

Light hits the photopigment

A photon is absorbed by rhodopsin (opsin + retinal) in the membrane discs.

Retinal changes shape from cis to trans.

Rhodopsin becomes activated photopigment.

G-protein activation

Activated rhodopsin activates the G-protein transducin.

One activated rhodopsin activates many transducin molecules.

This is the first amplification step.

Enzyme activation

Activated transducin activates phosphodiesterase (PDE).

PDE rapidly breaks down cGMP → GMP.

cGMP concentration falls sharply.

Ion channel effect

cGMP-gated Na⁺ channels close because cGMP is low.

Na⁺ influx into the outer segment stops.

K⁺ efflux from the inner segment continues.

Electrical consequence

Net effect is hyperpolarisation of the photoreceptor membrane.

Membrane potential becomes more negative (towards ~ –60 mV).

Synaptic consequence

Voltage-gated Ca²⁺ channels at the synaptic terminal close.

Less glutamate is released onto bipolar cells.

Light is signalled by a decrease in neurotransmitter release.

How is the phototransduction response terminated?

• All-trans retinal removed

• Opsin phosphorylated and inactivated

• Transducin deactivated

• cGMP restored → Na+ channels reopen → membrane returns to resting potential

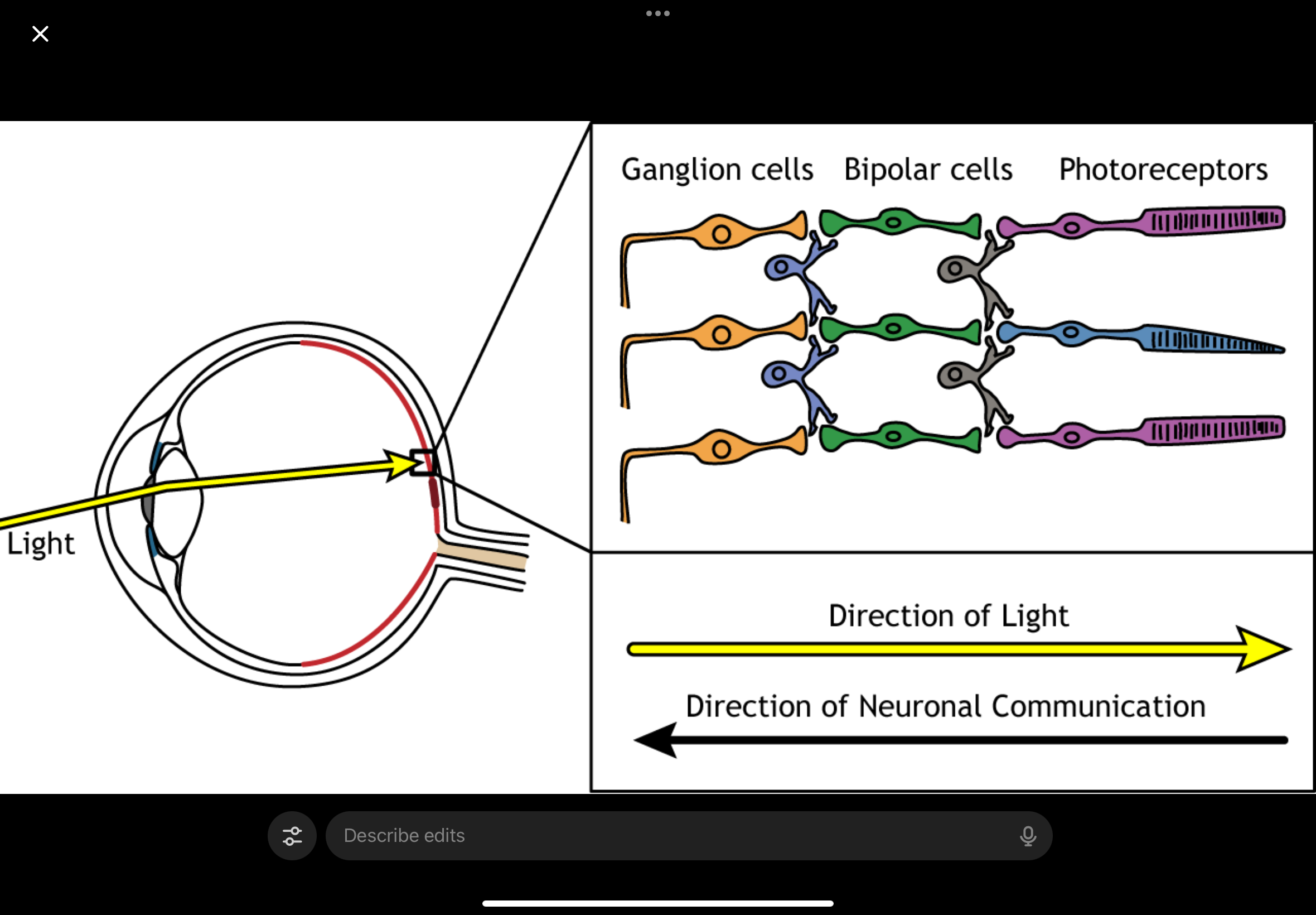

Ganglion cells, Bipolar Cell and Photoreceptor layout

Ganglion cells (closest to where light enters)

Bipolar cells

Photoreceptors (at the very back)

So when light enters the eye:

Light comes in

It passes through ganglion cells

Then passes through bipolar cells

Then finally reaches the photoreceptors

Light passing through a cell ≠ that cell responding to light

Ganglion and bipolar cells are transparent enough that light just passes through them

They do not detect light

Only photoreceptors:

Absorb the light

Convert it into an electrical signal

Then the signal goes the opposite way

Once photoreceptors respond:

Signal goes back up the layers:

Photoreceptors → bipolar cells → ganglion cells

Ganglion cells then send the signal out via the optic nerve

Light travels down to photoreceptors, but the signal travels back up to ganglion cells.

What is light adaptation?

Photoreceptors continuously adjust sensitivity based on background illumination.

This prevents saturation and allows the visual system to operate over a huge range of light intensities.

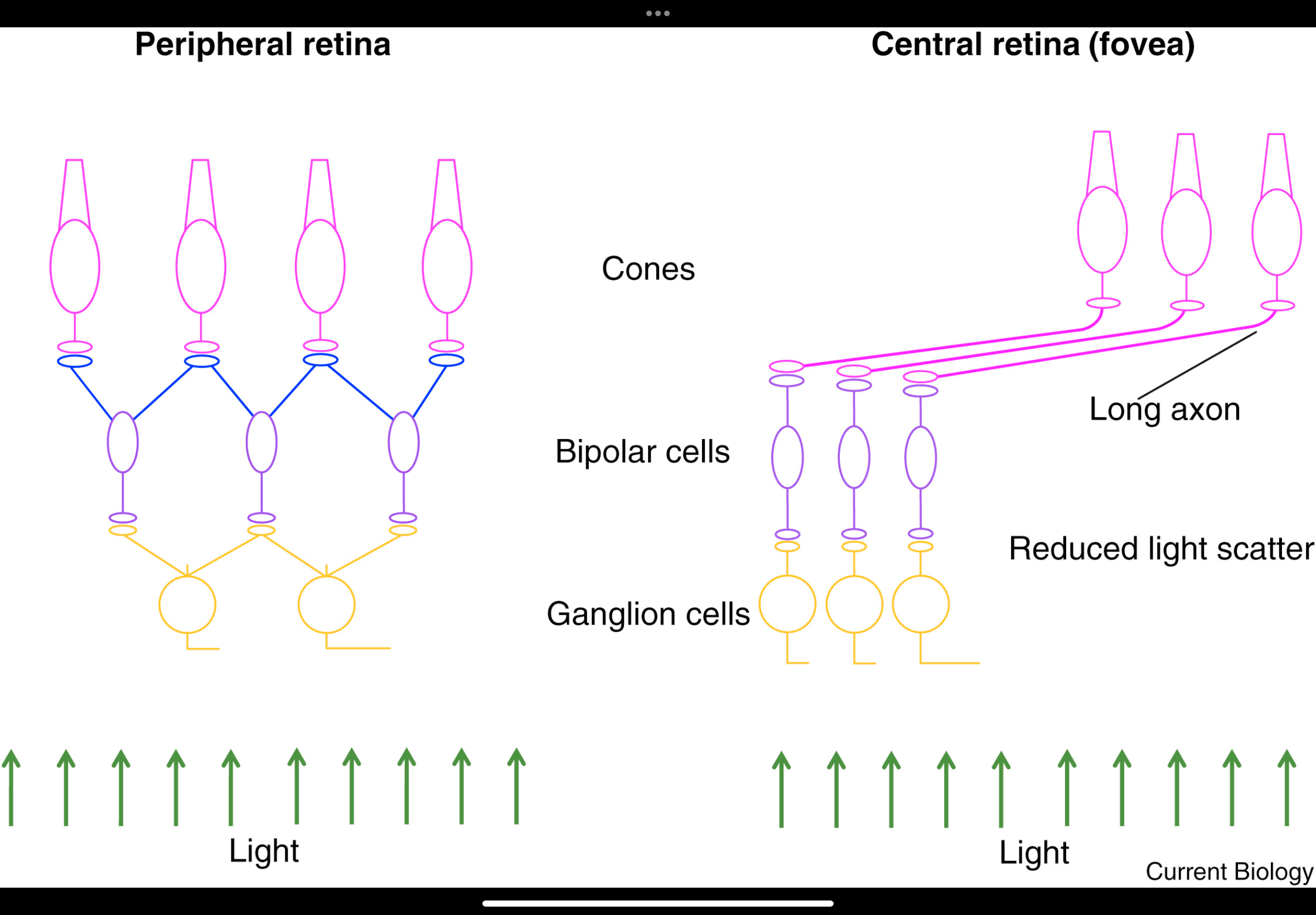

Peripheral Vision

The peripheral retina trades detail for sensitivity by pooling signals from many photoreceptors onto fewer ganglion cells, which creates large receptive fields and lower visual acuity.

Retinal layers (top to bottom)

Pigment epithelium

Absorbs stray light.

Supports photoreceptors metabolically.

Photoreceptors

Mostly rods in the peripheral retina.

Detect light but do not send signals directly to the brain.

Interneurons

Bipolar, horizontal, and amacrine cells.

Process and combine signals from multiple photoreceptors.

Ganglion cells

Final output neurons.

Their axons form the optic nerve.

Convergence

Many photoreceptors converge onto a single ganglion cell.

This pooling creates:

Large “pixels” (poor spatial resolution).

High sensitivity to dim light.

That’s why peripheral vision is good for detecting movement but bad for fine detail.

“Big gaps in sampling array”

Photoreceptors are more sparsely sampled for detailed spatial information.

Fine detail is lost because signals are averaged before reaching the brain.

Image blurring as light passes through

Light must pass through multiple retinal layers before reaching photoreceptors.

In the periphery, this contributes further to reduced image sharpness.

The system prioritises detection over precision.

Functional takeaway

Peripheral retina:

High rod density

High convergence

High sensitivity

Low acuity(detail)

This is ideal for:

Motion detection

Low-light vision

Awareness of surroundings

Peripheral vision = side vision

Low acuity = blurry / poor detail

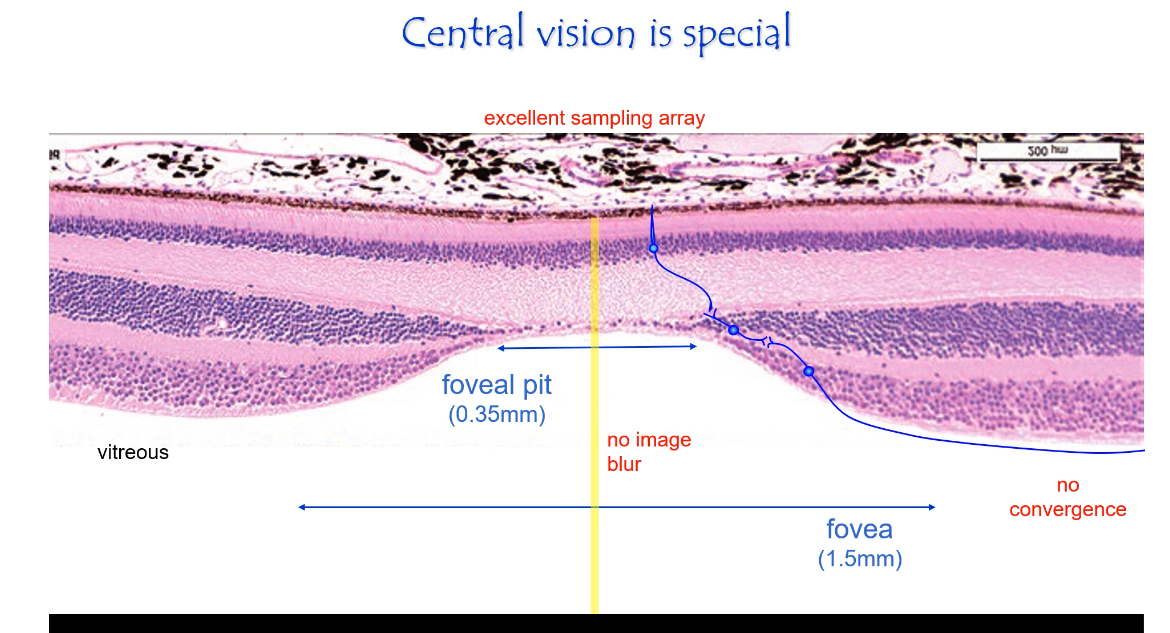

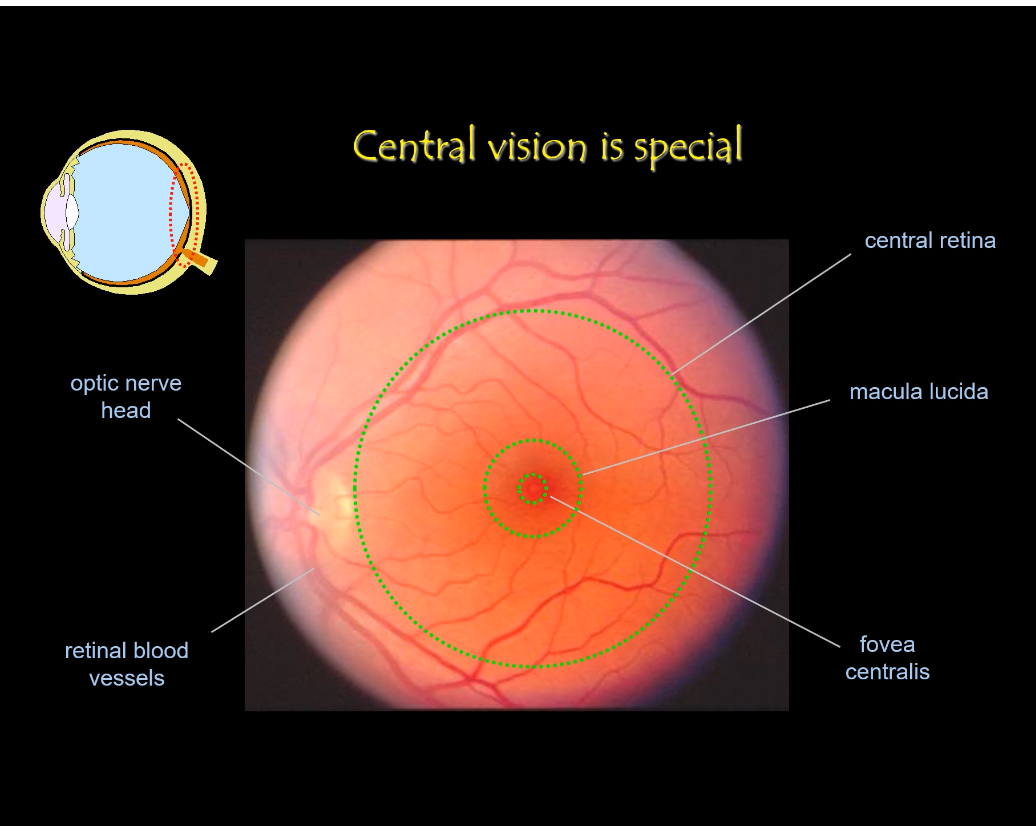

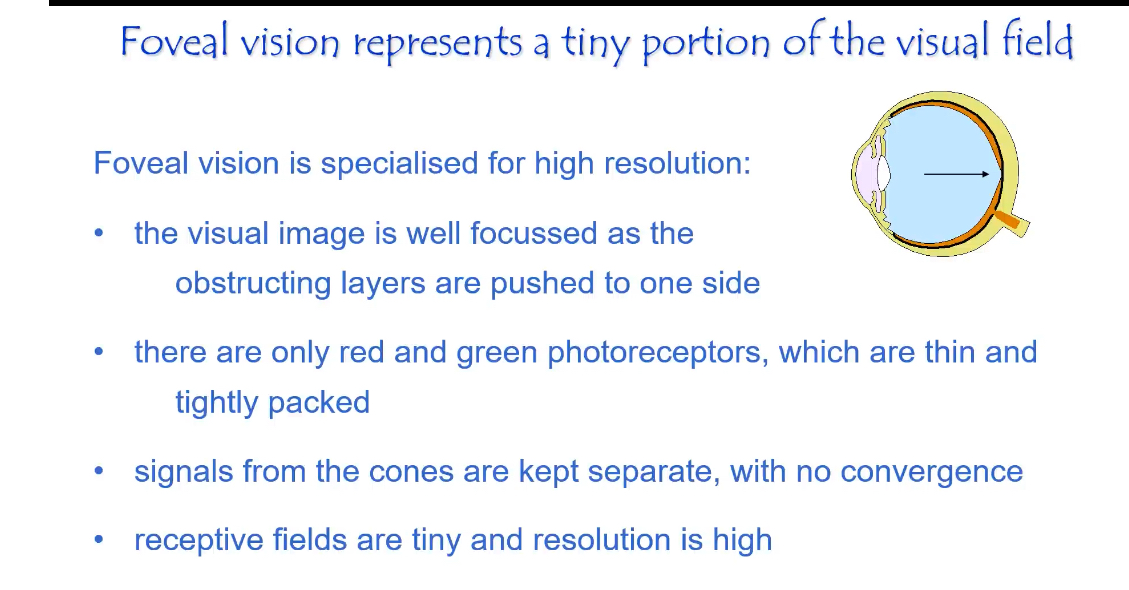

Central Retina

Location

Central retina includes the macula.

The very centre is the fovea centralis.

Excellent sampling array

Cones are small, densely packed, and regularly spaced.

Each cone samples a tiny part of the image.

Minimal convergence

Often 1 cone → 1 bipolar → 1 ganglion cell.

Signals stay separate instead of being pooled.

Reduced image blur

Inner retinal layers are pushed aside at the foveal pit.

Light reaches cones with minimal scattering.

Functional outcome

Very high acuity (sharp vision).

Essential for reading, recognising faces, colour vision.

Anatomical landmarks (fundus image)

Optic nerve head

Where ganglion cell axons leave the eye.

No photoreceptors here (blind spot).

Macula

Central retinal region specialised for detail.

Fovea

Centre of the macula.

Point of maximum visual acuity.

Retinal blood vessels

Sparse in the fovea to avoid blocking light.

Central vs Peripheral Retina

Central (fovea):

• Very high cone density

• No convergence — 1 cone → 1 bipolar → 1 ganglion cell

• Inner layers displaced → minimal optical blur

• Highest acuity

Central retina (fovea) = low sensitivity

Mostly cones

Cones need brighter light

Little/no convergence

Result:

Excellent detail and colour

Poor night vision

Peripheral:

• Mixed rods and cones; rods dominant

• Large spacing; low sampling density

• High convergence → many photoreceptors feed one ganglion cell

• Lower resolution, better sensitivity

Peripheral retina = high sensitivity

Many rods

Rods respond to very small amounts of light

Signals from many photoreceptors are added together (convergence)

Result:

Great night vision

Good at detecting movement

Poor detail

Photoreceptor layout

Cones are larger and more widely spaced.

Many rods sit between cones.

High convergence

Signals from many photoreceptors converge onto one ganglion cell.

This pooling averages information.

Effect of distance from fovea

The further from the fovea, the more convergence.

More convergence → lower resolution.

What clinical examples show importance of central vs peripheral vision?

Age-related macular degeneration: Loss of central vision

• Glaucoma, retinitis pigmentosa: Loss of peripheral vision

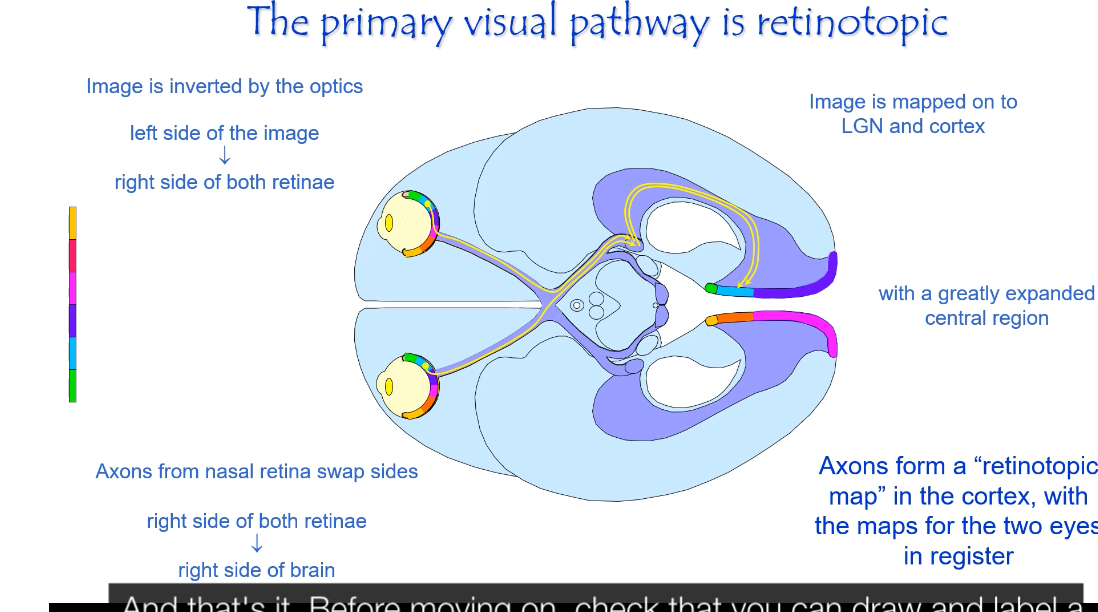

Retinotopic map

The primary visual pathway is retinotopic, meaning neighbouring points in the visual field stay neighbours all the way from the retina to the visual cortex.

Image inversion at the eye

The optics of the eye invert the image.

Left side of the visual world falls on the right side of each retina.

Right side of the visual world falls on the left side of each retina.

Top of the visual world falls on the bottom of the retina, and vice versa.

Sorting at the optic chiasm

Fibres from the nasal retina cross to the opposite side.

Fibres from the temporal retina do not cross.

Result:

Information from the right visual field goes to the left brain.

Information from the left visual field goes to the right brain.

Retinotropic mapping in LGN and cortex

After the optic chiasm, information is organised by visual field, not by eye.

The LGN preserves the spatial layout of the retina.

The primary visual cortex (V1) contains a detailed map of the visual field.

Points that are close together in the retina activate neurons close together in cortex.

Expanded central representation

The central retina (fovea) occupies a disproportionately large area in the visual cortex.

This is called cortical magnification.

Reason:

High cone density

Minimal convergence

High acuity

Peripheral retina occupies much less cortical space.

“Maps for the two eyes are in register”

Input from the left and right eyes is aligned.

Corresponding points from each eye activate the same cortical locations.

This allows binocular vision and depth perception.

Why is the cortical map distorted?

Cortical magnification (why maps look distorted)

Level: visual cortex

• The retina is mapped onto the visual cortex (retinotopy).

• But the map is not proportional.

Key fact:

• The fovea is tiny on the retina

• But it gets a huge amount of cortex

This is because:

Fovea has:

• High cone density

• Very small receptive fields

• Little convergence

• It carries much more detailed information.

This is called cortical magnification.

So when you see a “distorted” cortical map:

• It’s showing importance, not size.

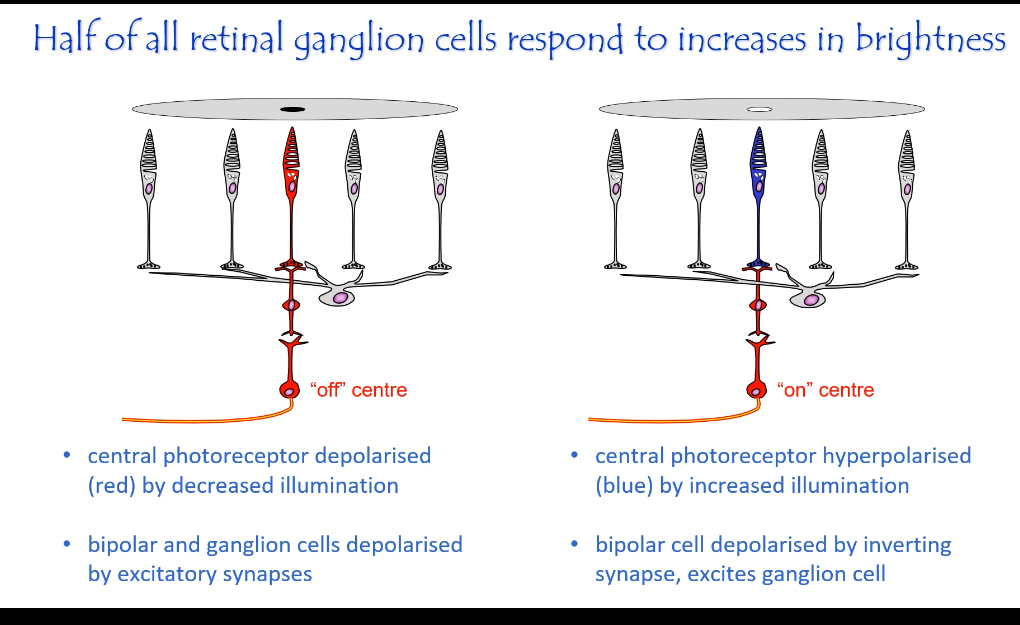

ON and OFF centre cells

1. Photoreceptors (rods and cones): where everything starts

Photoreceptors only control glutamate release.

Dark (no light):

Photoreceptor is depolarised

Releases a lot of glutamate

Light:

Photoreceptor is hyperpolarised

Releases less glutamate

Important:

Photoreceptors do not fire action potentials

They only signal by changing how much glutamate they release

Rule to memorise:

Dark → more glutamate

Light → less glutamate

2. Bipolar cells: why ON and OFF pathways exist

Bipolar cells do not detect light.

They read glutamate, and they differ because they express different glutamate receptors.

This is the only reason ON and OFF pathways exist.

ON bipolar cells — inhibitory glutamate receptor

Receptor:

mGluR6 (metabotropic, inhibitory)

Dark:

Lots of glutamate released

Glutamate activates mGluR6

Intracellular pathway closes cation channels

ON bipolar cell hyperpolarised

ON bipolar cell OFF

Light:

Less glutamate released

mGluR6 not activated

Cation channels open

ON bipolar cell depolarised

ON bipolar cell ON

Meaning:

ON bipolar cells respond when light increases

OFF bipolar cells — excitatory glutamate receptor

Receptors:

AMPA / kainate (ionotropic, excitatory)

Dark:

Lots of glutamate released

Glutamate activates AMPA/kainate receptors

Cation channels open

OFF bipolar cell depolarised

OFF bipolar cell ON

Light:

Less glutamate released

Fewer receptors activated

Cation channels close

OFF bipolar cell hyperpolarised

OFF bipolar cell OFF

Meaning:

OFF bipolar cells respond when light decreases

Important clarification:

ON and OFF bipolar cells are always present together

Light does not switch cells on or off

Light only changes their activity level

3. Ganglion cells: the output of the retina

Ganglion cells receive input from bipolar cells

They fire action potentials

Their axons form the optic nerve

This is the first place spikes occur.

ON-centre ganglion cell

Light in centre → firing rate increases

OFF-centre ganglion cell

Light in centre → firing rate decreases

Important definition:

Firing rate = action potentials in the optic nerve

It is not glutamate release

The firing pattern is generated at the ganglion cell and then carried unchanged through:

optic nerve

optic chiasm

optic tract

4. Horizontal cells: why the surround matters

Horizontal cells connect sideways between neighbouring photoreceptors

They provide lateral inhibition

They do not send signals to the brain

Inhibition here means:

Reducing the strength of the centre signal

Not shutting it off

Not killing the cell

Their job:

Allow photoreceptors in the surround to suppress the centre pathway

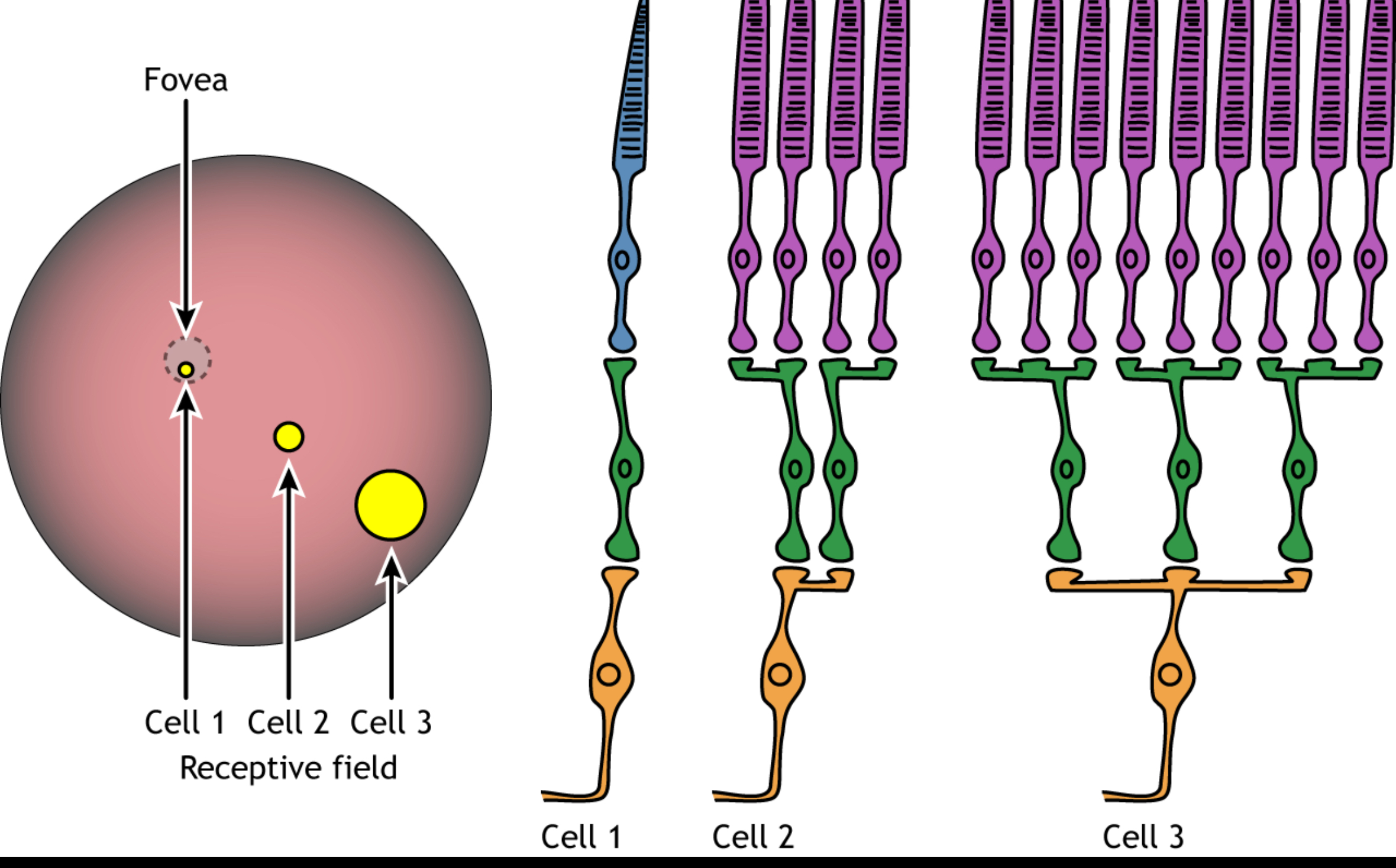

5. Centre–surround organisation

A ganglion cell does not judge the centre alone.

It compares:

a centre group of photoreceptors

a surround group of photoreceptors

Horizontal cells make the surround act opposite to the centre.

So:

Centre brighter than surround

→ centre signal dominates

→ ganglion cell fires stronglyCentre and surround equally bright

→ surround inhibition cancels centre

→ ganglion cell fires weaklySurround brighter than centre

→ opposite response

Key rule:

Ganglion cells fire strongly when the centre is different from the surround, not simply when the centre is bright.

This is how edges and contrast are detected.

6. Receptive field

A receptive field is:

A small patch of photoreceptors whose activity influences ONE ganglion cell

It is:

Not the whole retina

Not the whole visual world

A local group of rods/cones

Size depends on location:

Peripheral retina → large receptive fields (high convergence)

Fovea → tiny receptive fields (little or no convergence)

What are the main ganglion cell types and their features?

Parvocellular (P-cells):

• Small receptive fields

• High spatial resolution

• Slower

• Colour-sensitive (especially red–green comparisons)

• Important for fine detail and colour vision

Magnocellular (M-cells):

• Large receptive fields

• Fast conduction

• Sensitive to movement and luminance changes

How do ganglion cells compare cone outputs to signal colour?

• Red–Green cells: compare L cones vs M cones

• Blue–Yellow cells: compare S cones vs combination of L+M

This forms the basis of colour opponency.

Colour is encoded by comparing the outputs of different cone types, not by absolute activity in one cone.

That comparison is done by specialised ganglion cells using opponent wiring.

Step 1: Cone types (what is being compared)

You have three cone types:

L cones → long wavelengths (red-ish)

M cones → medium wavelengths (green-ish)

S cones → short wavelengths (blue-ish)

Each cone:

Signals light in the same ON/OFF way you already learned

Does not encode colour by itself

A single cone cannot tell colour — only brightness at that wavelength.

Step 2: What colour-opponent ganglion cells do

Some ganglion cells are wired so that:

Input from one cone type excites them

Input from another cone type inhibits them

So the ganglion cell is effectively asking:

“Which cone type is more active here?”

This is exactly the same logic as centre–surround, but applied to cone type instead of space.

Step 3: Red–Green opponent cells (L vs M)

These are usually parvocellular (P) ganglion cells.

Typical wiring:

Centre gets input from L cones

Surround gets input from M cones

(or vice versa)

So:

L > M → cell fires more → “red” (L-cone activity is stronger than M-cone activity in the surround)

M > L → cell fires less (or opposite cell fires) → “green”

Key point:

It is the difference between L and M activity that signals colour

Uniform stimulation of both → weak response

Step 4: Blue–Yellow opponent cells (S vs L+M)

These are a different set of ganglion cells.

Typical wiring:

S cone input opposed by

Combined L + M cone input

So:

S > (L+M) → “blue”

(L+M) > S → “yellow”

Again:

Colour = comparison, not absolute activation

Step 5: How ON/OFF fits into colour

Colour-opponent ganglion cells still:

Are either ON-centre or OFF-centre

Still fire action potentials

Still send signals via the optic nerve

ON/OFF encodes:

Light increments vs decrements

Opponent wiring encodes:

Which wavelength dominates

These two mechanisms run in parallel.

Step 6: Ganglion cell classes involved

Parvocellular ganglion (P-cells)

Small receptive fields

High spatial resolution

Slower

Colour sensitive (especially red–green)

Important for fine detail and colour vision

Magnocellular ganglion (M-cells)

Large receptive fields

Fast conduction

Sensitive to movement and luminance

Not colour sensitive

Visual Processing:

how visual information changes as it goes from retina → LGN → primary visual cortex → higher visual cortex, and what each stage is responsible for.

1. Retina → LGN: almost no transformation (faithful relay)

What LGN cells are like

• LGN neurons have centre–surround receptive fields

• They look almost identical to retinal ganglion cell receptive fields

• They respond best to:

• small spots of light

• contrast (light vs dark)

Meaning

• The LGN is not doing complex processing

• It mainly:

• relays retinal signals to cortex

• keeps ON/OFF, colour-opponent, M/P pathways separate

“LGN cells are a faithful relay”

2. Primary visual cortex (V1): first BIG change

What changes in V1

• Receptive fields are no longer circular

• Neurons respond best to:

• oriented edges

• specific angles

• specific locations

So instead of:

• “light in the centre of a circle”

V1 cells respond to:

• “a vertical edge here”

• “a diagonal line there”

How this happens

• A V1 neuron combines many LGN centre–surround inputs

• Lining them up creates edge selectivity

“Primary visual cortical fields are very different”

3. Retinotopy is preserved, but distorted

What “retinotopic” means

• Neighbouring points on the retina map to neighbouring points in cortex

Why the map is distorted

• The fovea takes up a huge amount of cortex

• Peripheral retina takes much less

This is called cortical magnification

• Not an error

• A design choice for high acuity vision

4. Higher visual cortex: specialised jobs

After V1, information splits into streams.

Ventral stream (temporal lobe) — “What is it?”

• Colour processing

• Shape

• Faces

• Object identity

This slide shows:

• colour-processing areas

• inferotemporal cortex

• the duck–rabbit illusion

The illusion shows:

• same visual input

• different object interpretation

→ object recognition is a cortical computation, not retinal.

Dorsal stream (parietal lobe) — “Where is it / how is it moving?”

• Motion

• Spatial location

• Visuomotor coordination

This pathway answers:

• where

• how fast

• in which direction