Social Psychology - Lectures 11 & 12

1/14

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

15 Terms

The Commonsense View vs. Alternative Possibilities

Commonsense View: People act consistently with their beliefs/attitudes, so no deep justification is needed.

Alternative: People infer their feelings and beliefs or attitude from their behavior.

When behavior conflicts with our attitudes, we often bring our beliefs/feelings into line with what we’ve already done (i.e., we change our internal attitudes to match our actions).

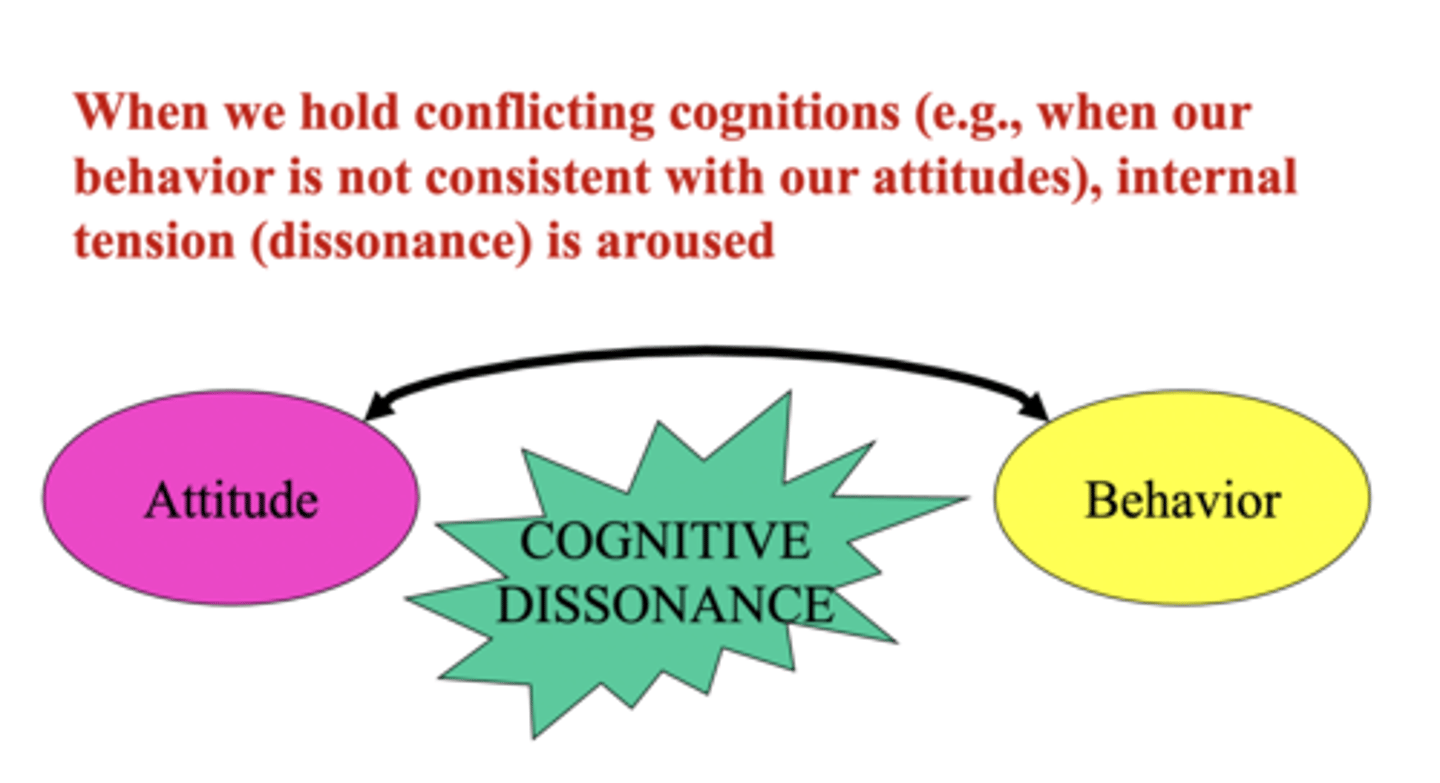

Festinger's Theory of Cognitive Dissonance

A distressing psychological tension occurring when our attitudes conflict with our behavior (or when two cognitions are inconsistent). We are motivated to reduce this tension—often by changing the attitude when we cannot alter the behavior (automatic; not conscious).

Dissonance = holding two conflicting cognitions, such as “I believe X” vs. “I just acted against X”

According to the tenets of cognitive dissonance theory, people are most likely to change their attitudes when they have insufficient external justification for an attitude-discrepant behavior.

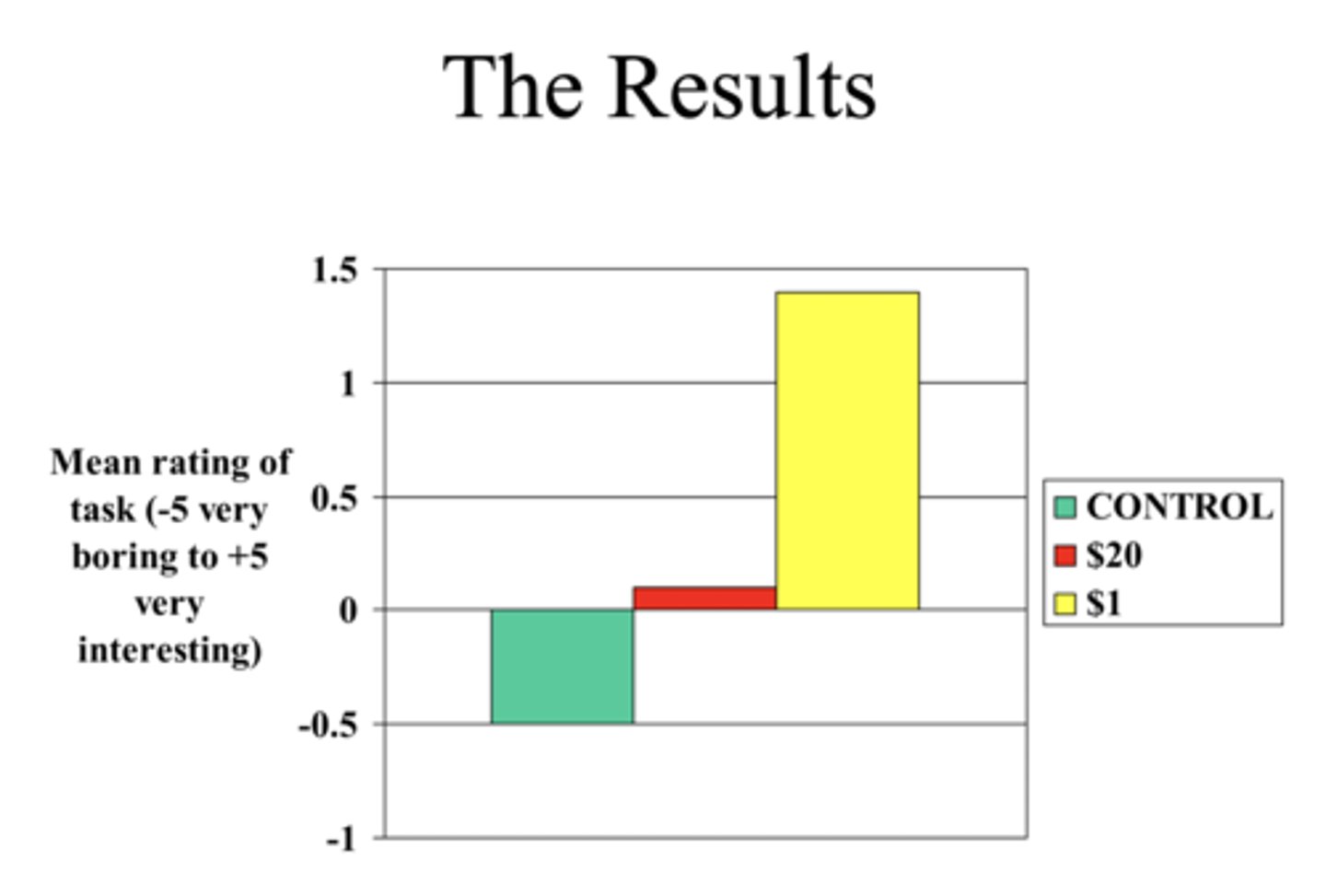

Festinger & Carlsmith (1959): The Boring Knob-Turning Task

Procedure: Participants did a tedious task for 1 hour, then were paid $1 or $20 to tell another person it was fun.

Results: Those paid $1 (insufficient external justification) later reported liking the task more than those paid $20.

Conclusion: Minimal external justification created high dissonance, so participants adjusted attitudes (“It wasn’t that bad!”) to reduce tension.

Counter-attitudinal advocacy: Contradicting one's current beliefs.

Reason:

$20 = Sufficient external justification → “I did it for the money.” Low dissonance, no big attitude shift.

$1 = Insufficient external justification → “Why did I lie for so little?” High dissonance, thus they convince themselves the task was actually fun.

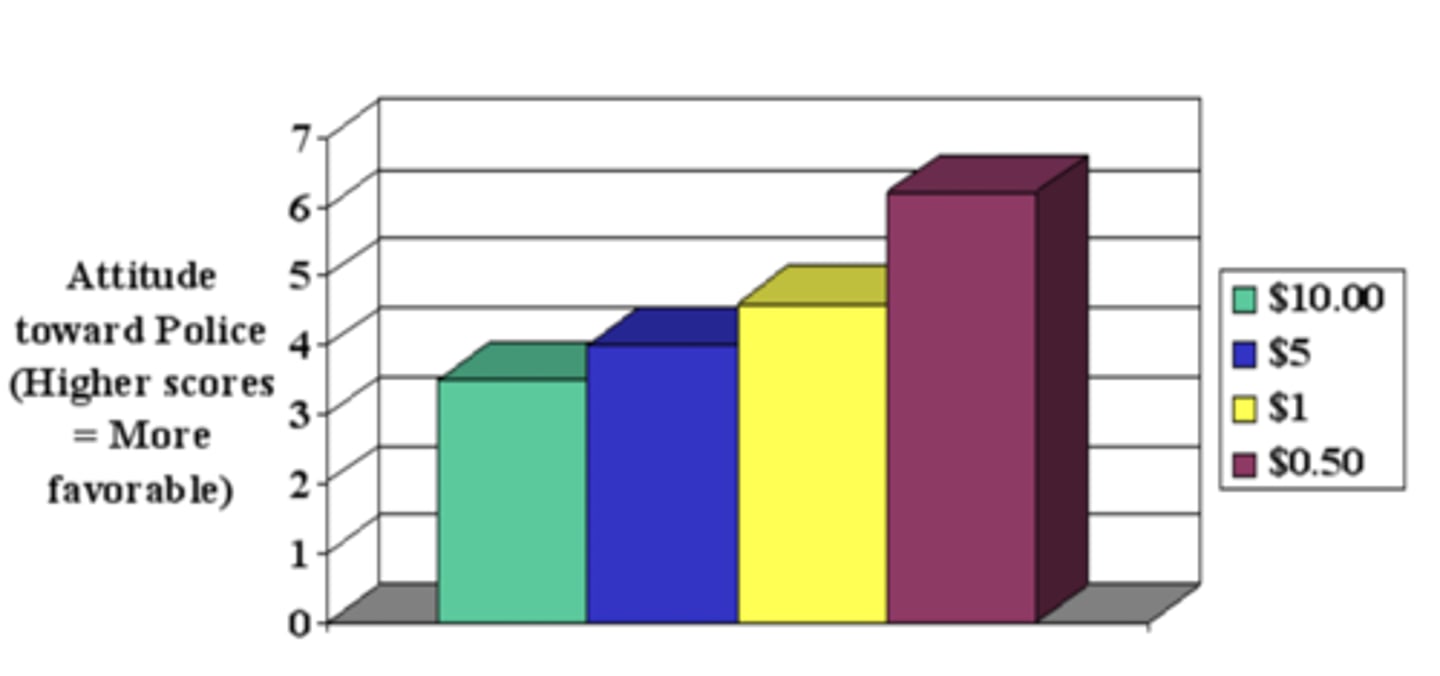

Cohen et al. (1962) and Counterattitudinal Advocacy

Procedure: Students wrote essays supporting police action against their personal beliefs (even though they were sometimes beaten).

Payment ranged from $0.50 to $10.

Results: Lower pay led to more positive post-essay attitudes, confirming that insufficient external justification triggers greater attitude change.

Key Takeaway: The larger the external reward, the less the cognitive dissonance.

Post-Decisional Dissonance (Brehm's Appliances & Knox's Racetrack Bettors)

After a difficult and permanent choice, we increase liking of the chosen option and decrease liking of the rejected (even though we rated them initially similar).

Brehm: Women who picked an appliance among close options rated the chosen one higher afterward.

They reduced dissonance by overestimating differences between chosen and rejected alternatives.

Knox: Bettors were more confident in their horse’s chances after placing the bet. When you placed the bet, dissonance Decreases.

Takeaway: When choices create conflicting cognitions, people upgrade the chosen option and downgrade the rejected one.

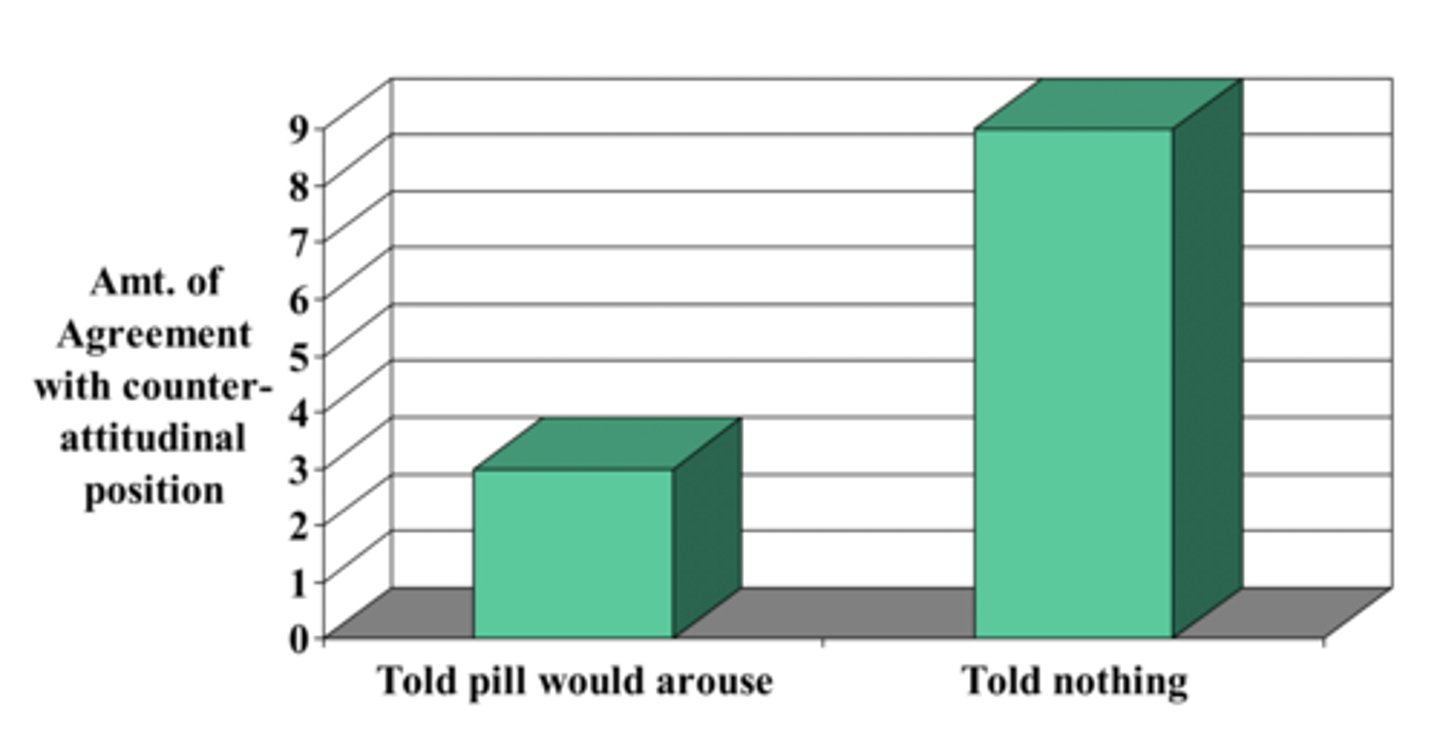

Arousal and the Zanna & Cooper (1974) Placebo Study

Dissonance isn’t just logical contradiction—It’s an unpleasant mental state with a neurophysiological basis.

Zanna & Cooper: Gave participants a “pill” (placebo), telling some it would make them tense (side effects).

If they expected tension from the pill, they blamed discomfort on it instead of their counterattitudinal essay, so less attitude change.

If they couldn’t blame the pill, they felt the tension from lying and changed their attitude more.

Results:

Group A (the “pill causes tension” group)

Blames any uneasy feeling on the pill → doesn’t feel pressure to fix the conflict → doesn’t change their attitude much.

Group B (the “neutral pill” group)

Can’t blame the feeling on the pill → realizes the discomfort is from going against their beliefs → tries to remove the discomfort by changing their attitude.

Why It Matters: Suggests that attributing arousal to the attitude-behavior inconsistency is an important component of the cognitive dissonance phenomenon

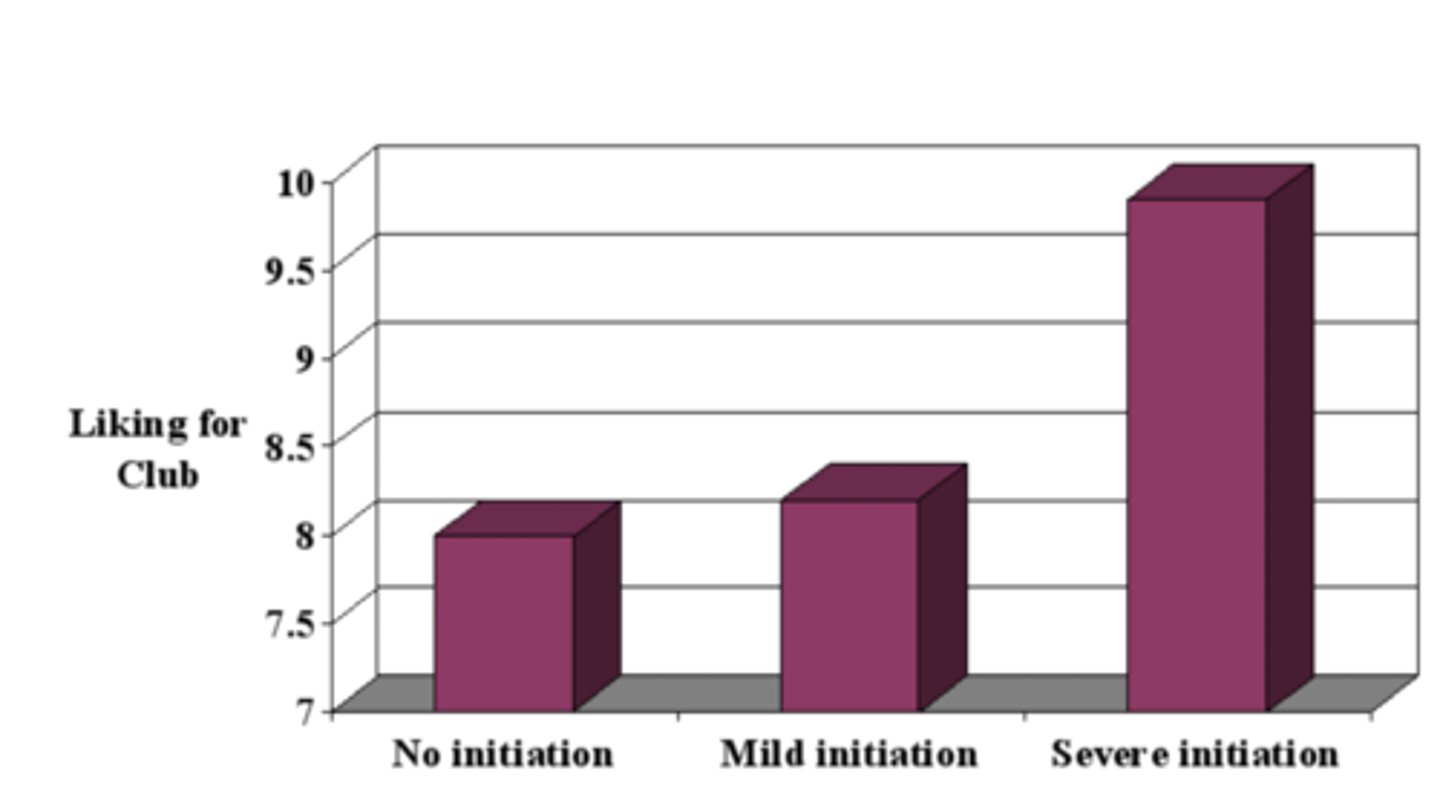

Justification of Effort (Aronson & Mills, 1959)

Core Idea: People who work hard or endure stress to join a group (ONLY VOLUNTARILY) often overvalue it afterward to justify the effort.

Procedure: College women join a discussion group.

Initiation Severity: Severe vs. Mild vs. None.

Severe required reading obscene words aloud (embarrassing/stressful).

Result: Those with the severe initiation ended up rating a dull, boring discussion more favorably—rationalizing their effort. None and Mild initiation wasn't much different!

Why It Matters: Shows how enduring something unpleasant leads us to convince ourselves it was “worth it,” changing attitudes to reduce dissonance.

They interpreted ambiguous aspects of the discussion in the most positive light possible.

Bem's Self-Perception Theory vs. Cognitive Dissonance

Self-Perception Theory (Bem): People infer their own attitudes by observing their behavior in a rational, non-arousal-based way (i.e., no internal tension or dissonance).

Make an attribution to our attitude from behavior

Example: “I keep ordering salad—maybe I really like salad.”

Cognitive Dissonance (Festinger): Attitude change results from psychological discomfort (arousal) when behavior and attitudes conflict.

Example: “I just lied for $1—I must actually like the task.”

Why It Matters: Both theories explain attitude shifts; dissonance often covers larger changes (tension-driven), while self-perception often explains how attitudes form initially or change under milder circumstances.

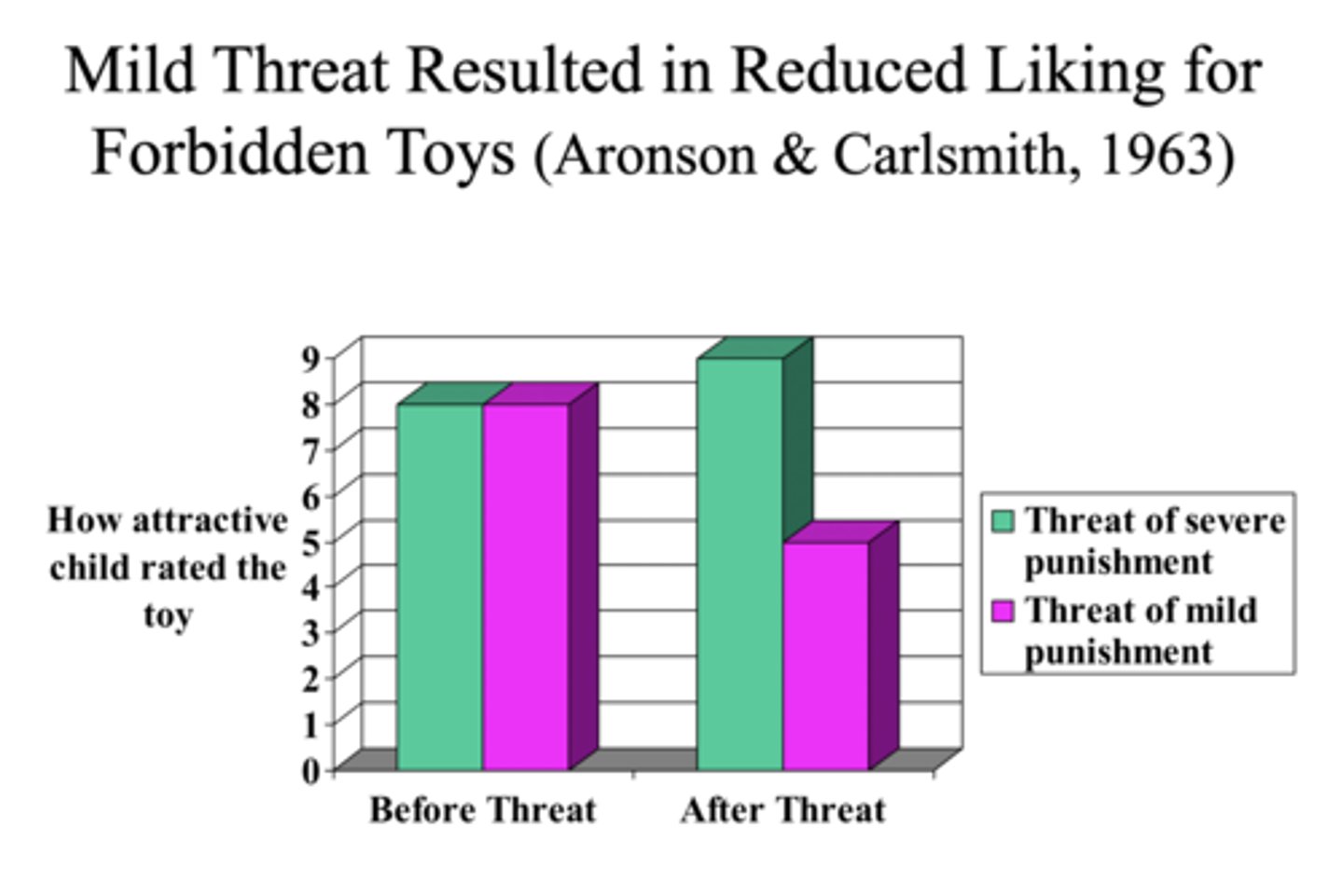

The Paradox of "Barely Sufficient" Punishment

Inadequate Justification: With a mild threat, people think “I’m not doing it, but the punishment isn’t scary—so maybe I just don’t want to do it.”

Leads to internal attitude change (“I guess that behavior isn’t so fun”) in the long-run.

Severe Threat: Provides an obvious external reason (“I’ll be severely punished!”).

People still like the forbidden behavior but avoid it from fear, not from any real change in preference.

Key Takeaway: Barely sufficient external pressure fosters true internal attitude shifts.

Mild Threat Studies: Aronson & Carlsmith (1963), Freedman (1965)

Aronson & Carlsmith (1963): Children are forbidden to play with a toy under either mild or severe threat.

Those in the mild-threat condition later rated the toy as less attractive than before (they convinced themselves they just didn’t like it).

Severe-threat children still liked the toy but avoided it only because of potential punishment; ample external justification for restraint.

Key Takeaway: mild threats reduced their dissonance by rating the forbidden toy as less attractive than before.

Freedman (1965): Showed the long-term effect. Even four weeks later, children under mild threat still avoided the toy, suggesting genuine attitude change.

Key Point: Mild threats create insufficient external justification, leading kids to devalue the forbidden object internally.

Why Mild Punishment is More Effective

Self-perception:

• Mild: I don’t do it because I don’t want to (e.g., "I'm not littering

• Severe: I don’t do it because of the threat (e.g., "I'm not littering because of the large fine)

Cognitive Dissonance:

• Mild: I want to do it; I’m not doing it, but the threat is insufficient justification (e.g., "I want to litter, but I'm not doing it, so I guess littering is bad" – High dissonance

• Severe: I want to do it; I’m not doing it because of the threat – Low dissonance

Self-Perception vs. Cognitive Dissonance

Self-Perception Theory: People observe their behavior (“I didn’t play with the toy under a mild threat”) and infer they don’t like it much.

Emphasizes a non-arousal, inference-based process (“I guess that’s who I am”)..

Cognitive Dissonance Theory: Inconsistency (“I want it but I’m not playing with it”) creates psychological discomfort (arousal), leading to attitude change (“maybe I don’t like the toy”).

Complementary, Not Exclusive: Self-perception often describes attitude formation (especially when stakes are low).

Cognitive dissonance is better at explaining larger, arousal-driven attitude changes (especially when the behavior is clearly inconsistent with strong prior attitudes).

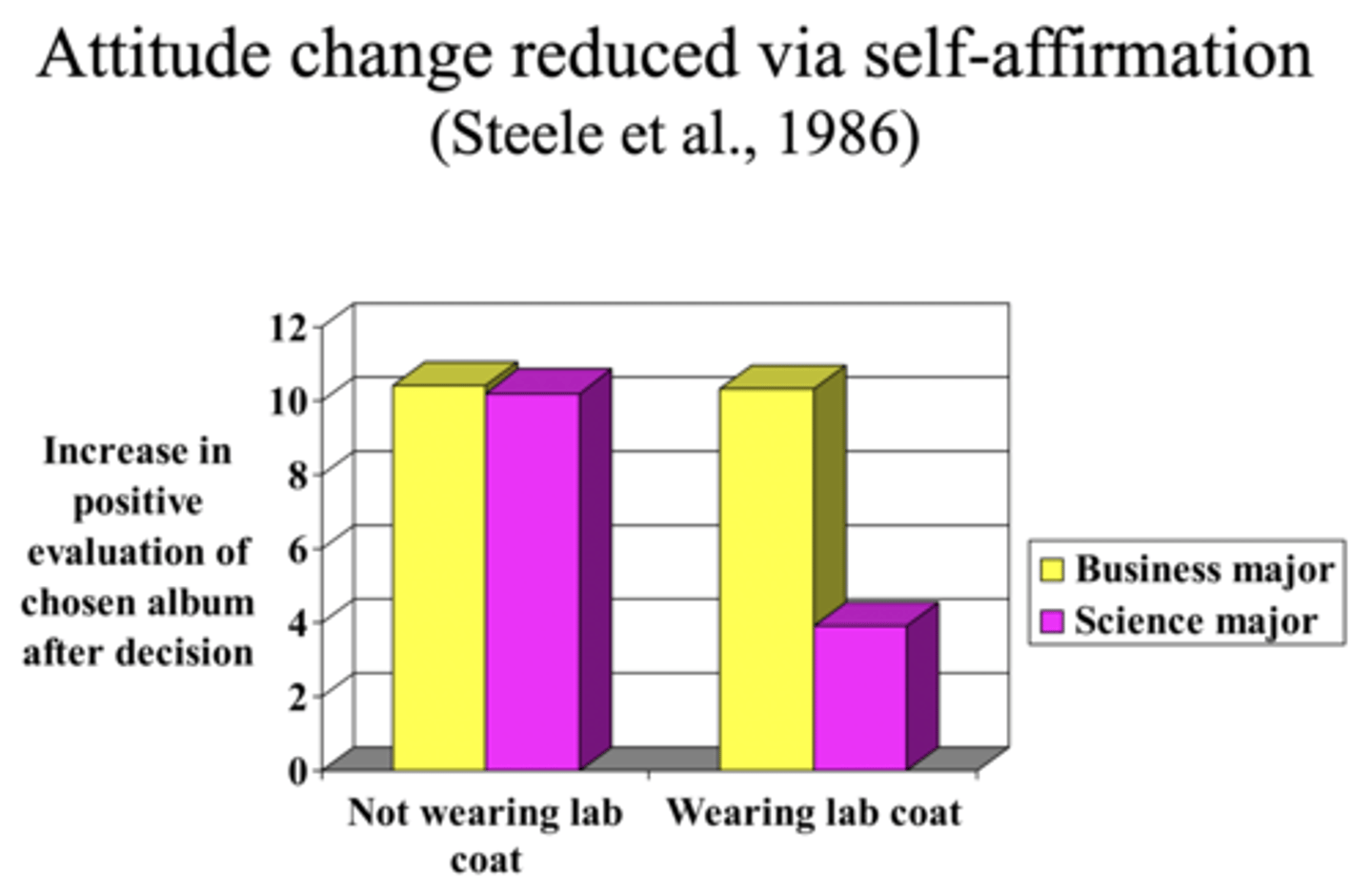

Self-Affirmation Theory

Core Concept: Attitude-Behavior inconsistency threatens our SE. We recover it by changing attitude to match behavior.

Unique Prediction: We can reduce the threat by affirming our competence or goodness on another, unrelated dimension –which will eliminate or reduce the attitude change.

Steele et al. (1986) - The Lab Coat Study

Design: Participants chose between two equally desirable music albums (normally triggers post-decisional dissonance).

Some participants (particularly science majors) donned a white lab coat, presumably symbolizing their competence or identity in science.

Finding: Those who self-affirmed by wearing the lab coat did less “spreading of alternatives” afterward (i.e., they didn’t inflate the chosen album or downgrade the rejected one as much).

The coat had no effect for non–science majors, indicating that the self-affirmation worked only if it meant something (e.g., revalidating their scientific identity).

Implication: By affirming their self-worth on an unrelated dimension, they felt less need to adjust their attitudes to resolve any dissonance from their choice.

This supports the self-affirmation explanation for why attitudes might change—or might not change—under certain conditions.

Cognitive Dissonance, Self-Perception, and Self-Affirmation

Similarities:

All three explain the attitude-behavior change or why attitudes change to match behavior.

Differences:

SP theory is better at explaining attitude formation from behavior.

CD theory is better at explaining attitude change by reducing discomfort/tension.

SA theory is better at explaining attitude stability by reducing the need to justify their actions.