6.0 Acute respiratory distress syndrome

1/24

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

25 Terms

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

a type of respiratory failure characterized by rapid onset of widespread inflammation in the lungs.

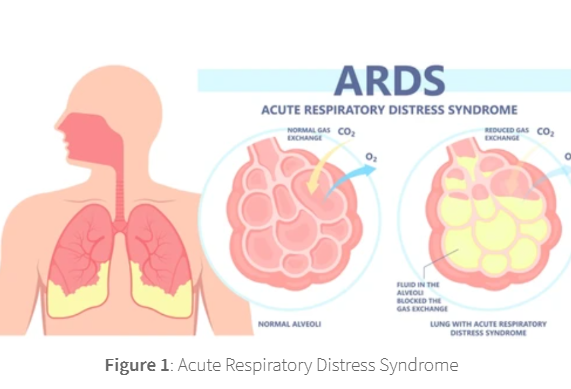

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening lung injury

that develops following injury to the capillary endothelium of the alveolar space.

This injury results in diffuse alveolar damage, where extracellular fluid seeps into the alveolar space

thereby restricting the ability of air to reach the alveolar membrane and for gaseous exchange to occur.

ARDS usually occurs in people who are already critically ill or have major injuries,

many of which will already be inpatients in hospital with related disease.

The severity of ARDS means that most patients will not survive,

with an increased mortality rate observed in the elderly.

Of the people who survive ARDS, some fully recover,

but others have chromic resulting lung damage.

ARDS has many risk factors which induce the inflammation to trigger the cascade that induces the syndrome.

People are especially at risk if they have an pulmonary infection, such as pneumonia or pulmonary aspiration.

pulmonary aspiration

the entry of solid or liquid material like pharyngeal secretion, food, drink or stomach contents from the oropharynx/ GI tract INTO the trachea + lungs → infection

In addition to pulmonary infection or aspiration, extra-pulmonary sources include:

Sepsis.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Head, chest or other major injury.

Breathing in harmful substances. .

Other conditions and treatments.

Advanced age,

smoking,

alcohol use

being female.

Drugs.

Sepsis.

The most common cause of ARDS is sepsis, a serious and widespread infection of the bloodstream.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

People who have severe COVID-19 may get ARDS. Because COVID-19 mainly affects the respiratory system, it can cause lung injury and swelling that can lead to COVID-19-related ARDS.

Head, chest or other major injury.

Accidents, such as falls or car crashes, can damage the lungs or the portion of the brain that controls breathing.

Breathing in harmful substances.

Breathing in a lot of smoke or chemical fumes can lead to ARDS, as can breathing in vomit. Breathing in water in cases of near-drownings also can cause ARDS.

Other conditions and treatments.

Swelling of the pancreas (pancreatitis),

massive blood transfusions

and severe burns can lead to ARDS.

Advanced age, smoking, alcohol use and being female.

Drugs.

Including radiation, chemotherapeutic agents and amiodarone

These extra-thoracic illnesses/injuries trigger an inflammatory cascade,

culminating in pulmonary injury

The seriousness of Acute respritory disease syndrome symptoms can vary depending

on the underlying aetiology + whether there is underlying heart or lung disease.

Symptoms of acute respiratory disease syndrome include:

Severe shortness of breath.

Laboured and rapid breathing that is not usual.

Cough.

Chest discomfort.

Fast heart rate.

Confusion and extreme tiredness.

ARDS can cause other medical problems while in the hospital, including:

Blood clots.

Collapsed lung, also called pneumothorax.

Infections.

Scarred and damaged lungs, known as pulmonary fibrosis.

Stress ulcers.

Blood clots.

Lying still in the hospital while you're on a ventilator can make it more likely that you'll get blood clots, particularly DVT

If a clot forms in your leg, a portion of it can break off and travel to one or both of your lungs, where it can block blood flow → pulmonary embolism.

Collapsed lung, also called pneumothorax.

In most people with ARDS, a breathing machine called a ventilator brings more oxygen into the body and forces fluid out of the lungs.

But the pressure and air volume of the ventilator can force gas to go through a small hole in the very outside of a lung and cause that lung to collapse.

Infections.

A ventilator attaches to a tube inserted in your windpipe. This makes it much easier for germs to infect and injure your lungs.

Scarred and damaged lungs, known as pulmonary fibrosis.

Scarring and thickening of the tissue between the air sacs in the lungs can occur within a few weeks of the start of ARDS.

This makes your lungs stiffer, and it's even harder for oxygen to flow from the air sacs into your bloodstream.

Stress ulcers.

Extra acid that your stomach makes because of serious illness or injury can irritate the stomach lining and lead to ulcers.