Social Psychology - Lectures 9 & 10

1/21

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

22 Terms

Definition of an Attitude

An attitude is an evaluative orientation toward a specific object—favorable or unfavorable, positive or negative. It can be toward anything: a person, group, political system, or even a food.

Attitudes have three parts (the ‘ABCs’):

Affect – How you feel (emotional component)

Cognition – What you believe (thoughts, ideas)

Behavior – How you act (predisposition to act)

Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Components (guns)

Cognitive (beliefs, ideas): Someone in favor of strict gun control might believe that "gun owners end up shooting themselves more often than they shoot thieves."

Affective (feelings, emotions): They might say, "Guns frighten me.”

Behavioral (actions): They might vote for gun-control advocates or contribute money to candidates who support stricter laws.

Origins of Attitudes

Infants have few attitudes (e.g., they might show disgust to a taste)

Cognitively-based: Based on beliefs—like buying a car because it’s fuel-efficient or reliable. That’s not about feelings; it’s about the facts or features.

Affectively-based (via learning): Classical and operant conditioning shape emotional responses—for example, getting punished or rewarded for expressing certain views.

Linked to personal values

Behaviorally-based (self-perception): Sometimes our behavior tells us our attitude. If you repeatedly do something, you infer you like it.

Genetically-based: Genes predispose us, but experience disposes us. Genes don’t cause specific attitudes; they just make it easier or harder to acquire certain attitudes; your experience pushes you the rest of the way.

Example: There’s no gene for liking Chinese food or supporting a specific political party.

The Attitude-Behavior Link

Attitudes are not always good predictors of behavior.

Classic studies (LaPiere, Wicker) showed people say one thing but do another, often because of external pressures like economic pressure or social desireability

Strength/Accessibility: Strong, accessible attitudes predict behavior better. If I can say right away ‘I love it’ or ‘I hate it,’ that attitude is stronger. (quickness predicts strength).

Direct vs. Indirect Acquisition: Direct attitudes formed directly from personal experience (e.g., eating a food) are more predictive than those formed indirectly (e.g., getting opinion about food).

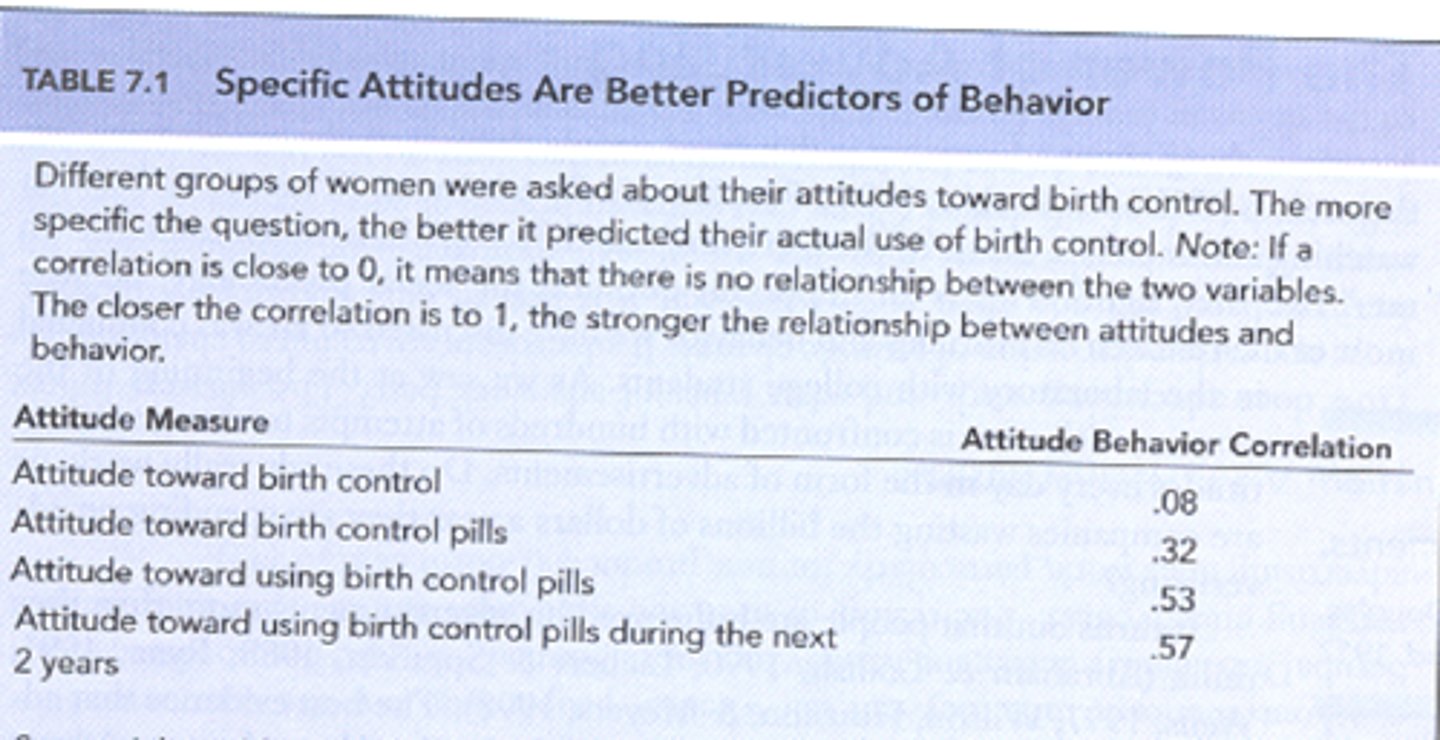

Congruent Specificity: Match the specificity of the attitude to the specific behavior. General attitudes predict broad behaviors, not narrowly defined ones.

Social Desirability: People may hide true attitudes to appear ‘politically correct,’ creating low attitude-behavior correlations. (except in anonymous situations).

Theory of Planned Behavior (Controlled Processes)

Specific Attitude toward the behavior (congruent specificity): Make sure your attitude matches exactly what you’re measuring—this is congruent specificity.

Subjective Norms: You need support from others—like your family, friends, or doctor endorsing your plan.

Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC): You have to believe you can do it—think of it like self-efficacy for that specific task.

When all three are present, you form a Behavioral Intention (mental plan), which is the best predictor of controlled, conscious behavior—but remember, a lot of our behavior is actually automatic.

Implicit vs. Explicit Attitudes

Explicit Attitudes are what you’re aware of and can report—like when you fill out a questionnaire.

Implicit Attitudes are deeper, possibly conflicting feelings or beliefs you might not even know you have. They often guide behavior when you’re not actively, consciously thinking things through.

Persuasion - The Process of Attitude Change

Changing the attitude is a means-end process (plan/execute).

Source: Who or what is doing the persuading—an individual, organization, group, etc.

Target: The person or group at whom the persuasion attempt is directed.

Message: The content and nature of the persuasive appeal—often words, but could be images or music.

Discrepancy: How far the message is from the target’s current attitude (large, moderate, or small discrepancy).

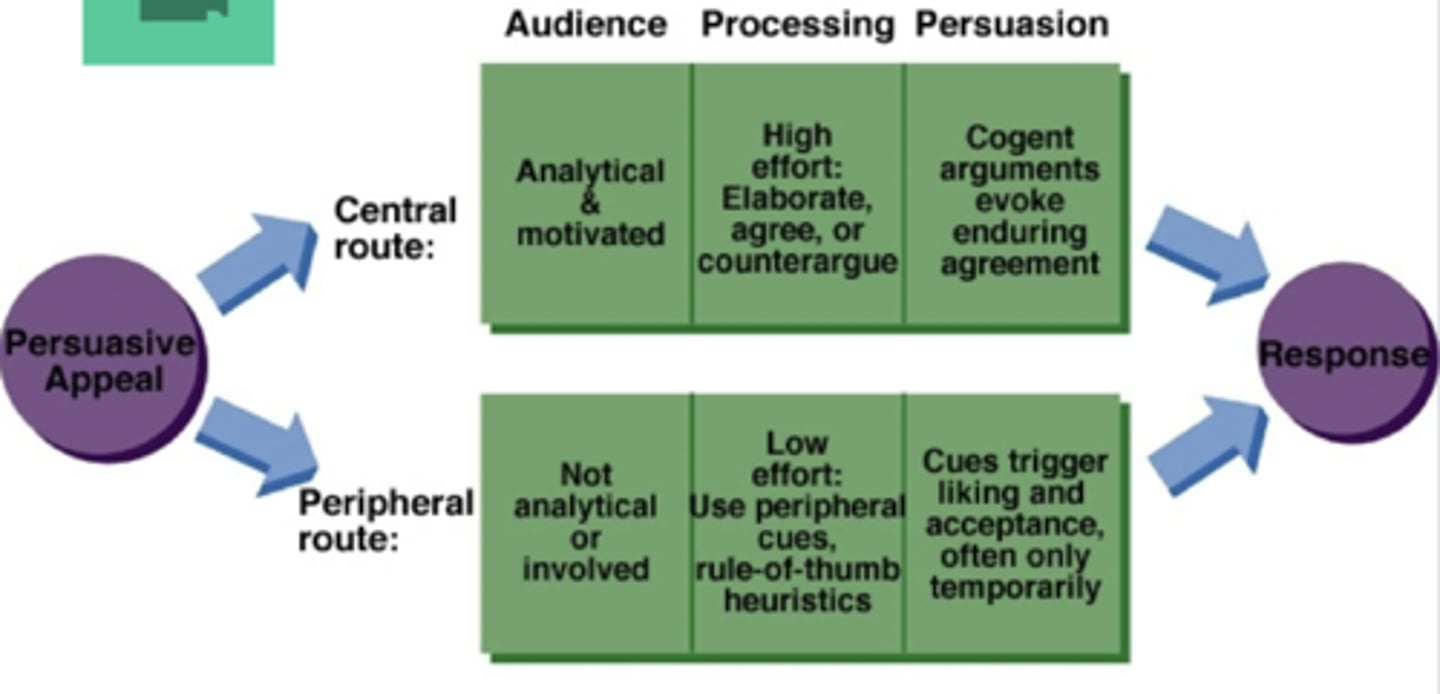

Central vs. Peripheral Routes to Persuasion

Peripheral Route (Automatic, Default)

Low-effort. We rely on quick cues: "This person looks confident," or "They made me laugh, so I believe them."

Leads to temporary attitude shifts—ephemeral liking that quickly fades.

This is most common in advertising: entertaining, simple messages with minimal info.

Central Route (Controlled)

High-effort. We’re motivated, have the time and mental resources to think carefully about arguments and evidence.

More enduring attitude change—long-lasting and more predictive of behavior change.

Harder to achieve because people need to be engaged and willing to process

Source Variable in Persuasion

Attractiveness: Can be physical or social “likable.” Attractive sources tend to be more persuasive via peripheral cues.

Credibility

Perceived Expertise: Based on credentials (e.g., diplomas, awards) and speech cues (fluent, confident delivery).

Perceived Trustworthiness: If the source argues against its own self-interest, we see them as more honest.

Perception of Persuasive Intent: If the source is obviously trying to change our minds for its own benefit or seems compensated, we’re less persuaded.

All of these are peripheral-route cues—if the audience is thinking centrally, source factors matter far less.

Target Variables in Persuasion

Expertise (Knowledge Level): If you don’t know anything about nuclear power, you can’t assess strong vs. weak arguments. Experts can process centrally more easily.”

Involvement / Self-Relevance: If it matters to you or you show you care, you’ll engage in central processing. If you’re indifferent, you’ll rely on peripheral cues.

Example: “When the university threatened your graduating class with a new final exam requirement, you got highly involved. Strong arguments worked best; weak arguments backfired.

Need for Cognition: People who love to think—puzzles, deep books—are more prone to go central. They’ll scrutinize arguments. Those low in need for cognition stick to peripheral cues.

Gender: Older studies found women were sometimes more easily persuaded, especially in political domains historically viewed as "male topics." But it likely depended on expertise and involvement. Modern data may differ.

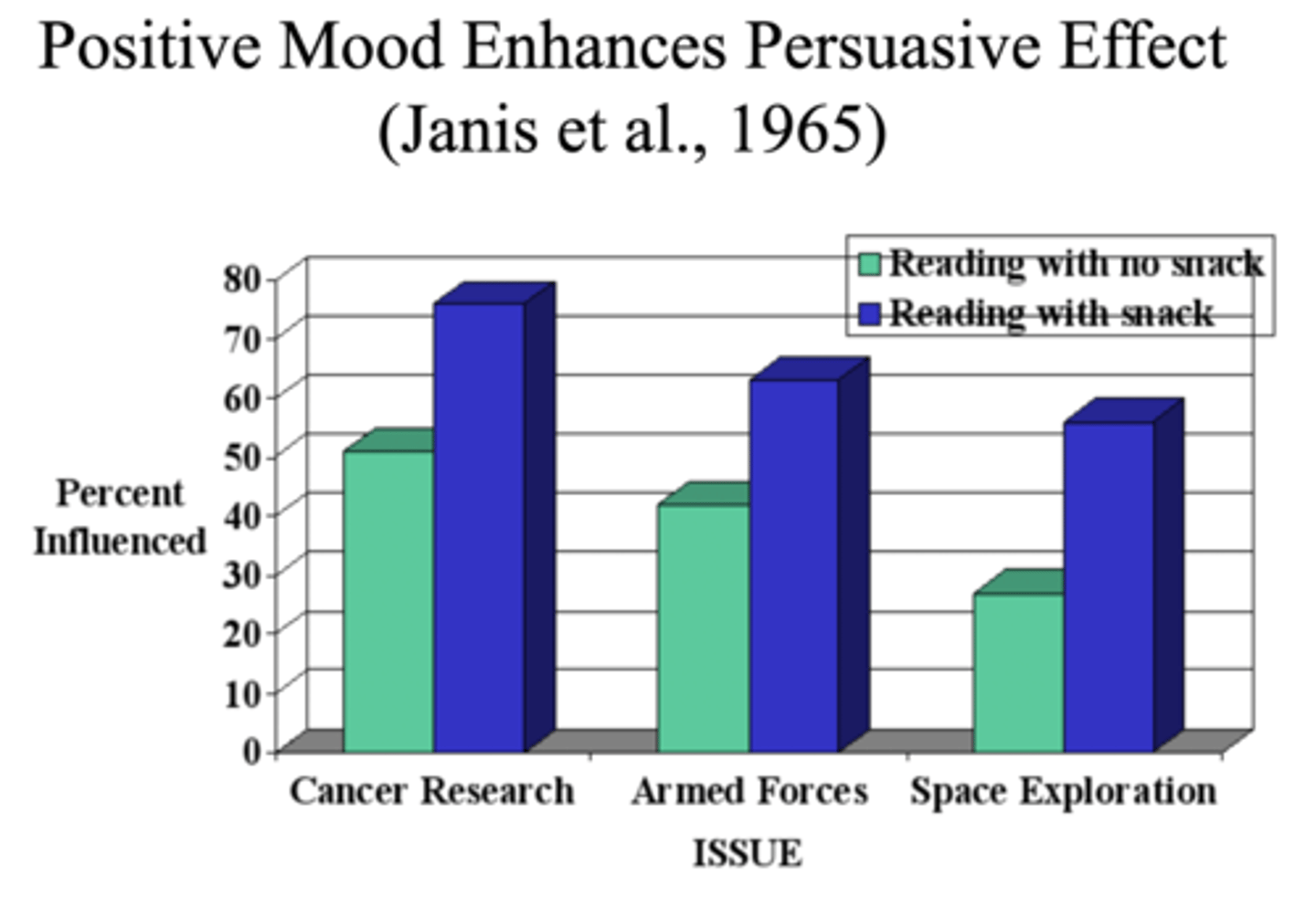

Mood Effects: Mildly Positive (Peanuts & Pepsi Study)

Does putting people in a good mood make them more persuadable or in a bad mood? It depends...

When people got a mildly pleasant snack (peanuts & Pepsi) while reading persuasive messages, they were more likely to agree with the content—positive mood made them more agreeable (peripheral). Those who read the same messages without the snack were less influenced.

Good moods don't pay attention to the quality of the persuasive message because they don't want to be distracted from their mood (i.e., they don't want to interrupt the good mood).

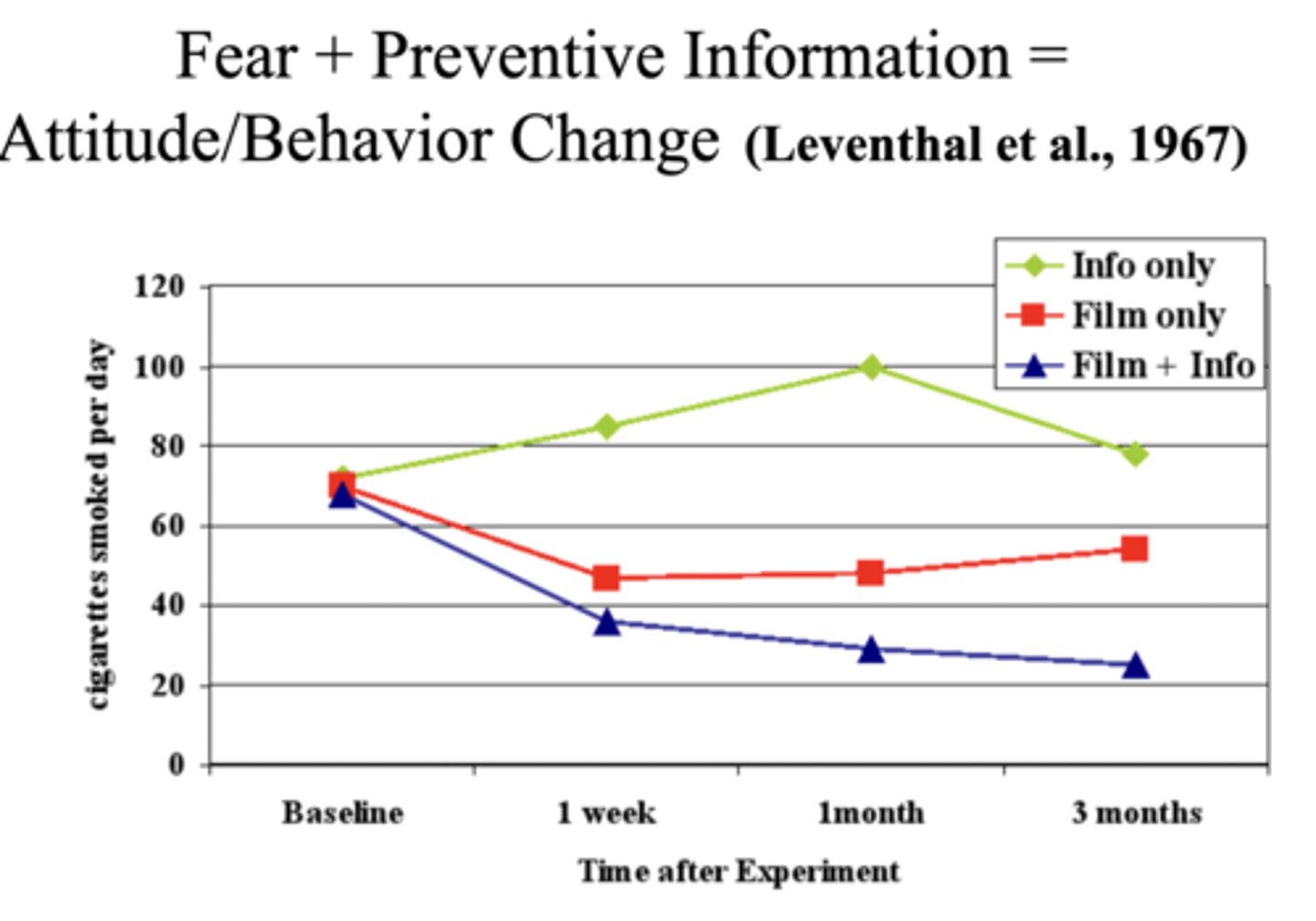

Mood Effects: Fear + Information (Leventhal et al.)

Information only (“Here’s how to quit”) did not reduce smoking (instead, smoking increased then start returning to baseline).

Film only (grotesque film of smoker’s autopsy) produced an initial drop but did not hold over time.

Film + Quitting Instructions had the strongest long-term impact.

Key Takeaway: A strong emotional reaction (fear/disgust) plus giving people a way to avoid the feared outcome produced lasting behavior change.

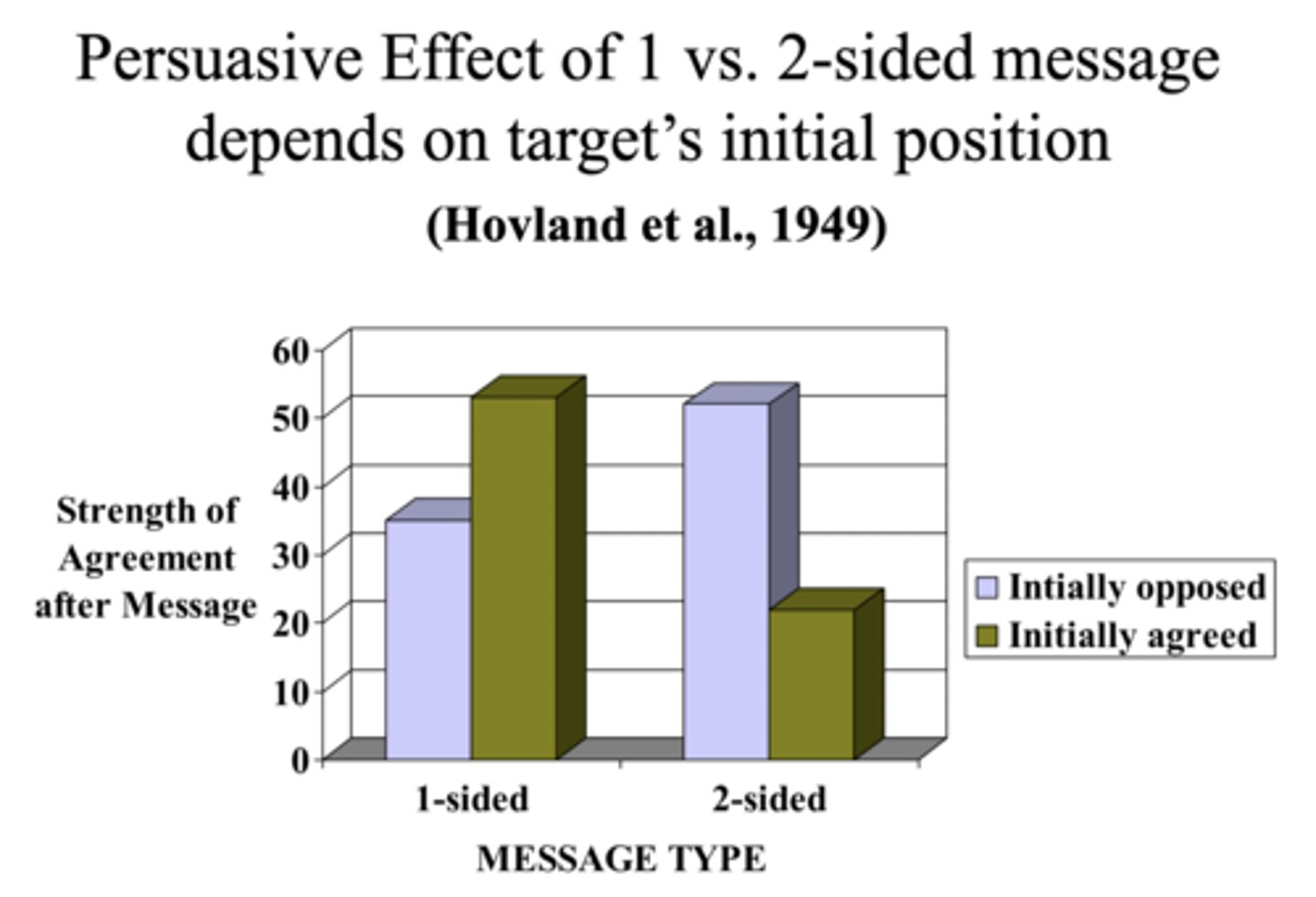

One-Sided vs. Two-Sided Messages

It depends on the target’s initial position:

If they already agree, a one-sided message (only the pros of your position and cons of opposing position) reinforces their view—greater persuasion.

If they initially oppose, a two-sided message (pros and cons on both sides) looks fair and balanced, increasing persuasion. But, it backfires for those who initially agreed (increasing doubt & uncertainty).

This is an interaction: the effect of message type depends on the audience’s initial attitude (or the effect of 1st IV depends on the level of the 2nd IV).

Message Discrepancy & Latitudes of Acceptance

Message Discrepancy is how far the message is from the target's current attitude.

Large Discrepancy → Falls in latitude of rejection; the target dismisses it, so no attitude change (e.g., if someone opposes nuclear power and you tell them how wonderful it is).

Small Discrepancy → Falls in latitude of acceptance; easily accepted, but little attitude change (e.g., if someone opposes nuclear power and you tell them that's true).

Moderate Discrepancy → Falls in latitude of non-commitment; yields maximal potential change if the arguments are strong or the source is credible.

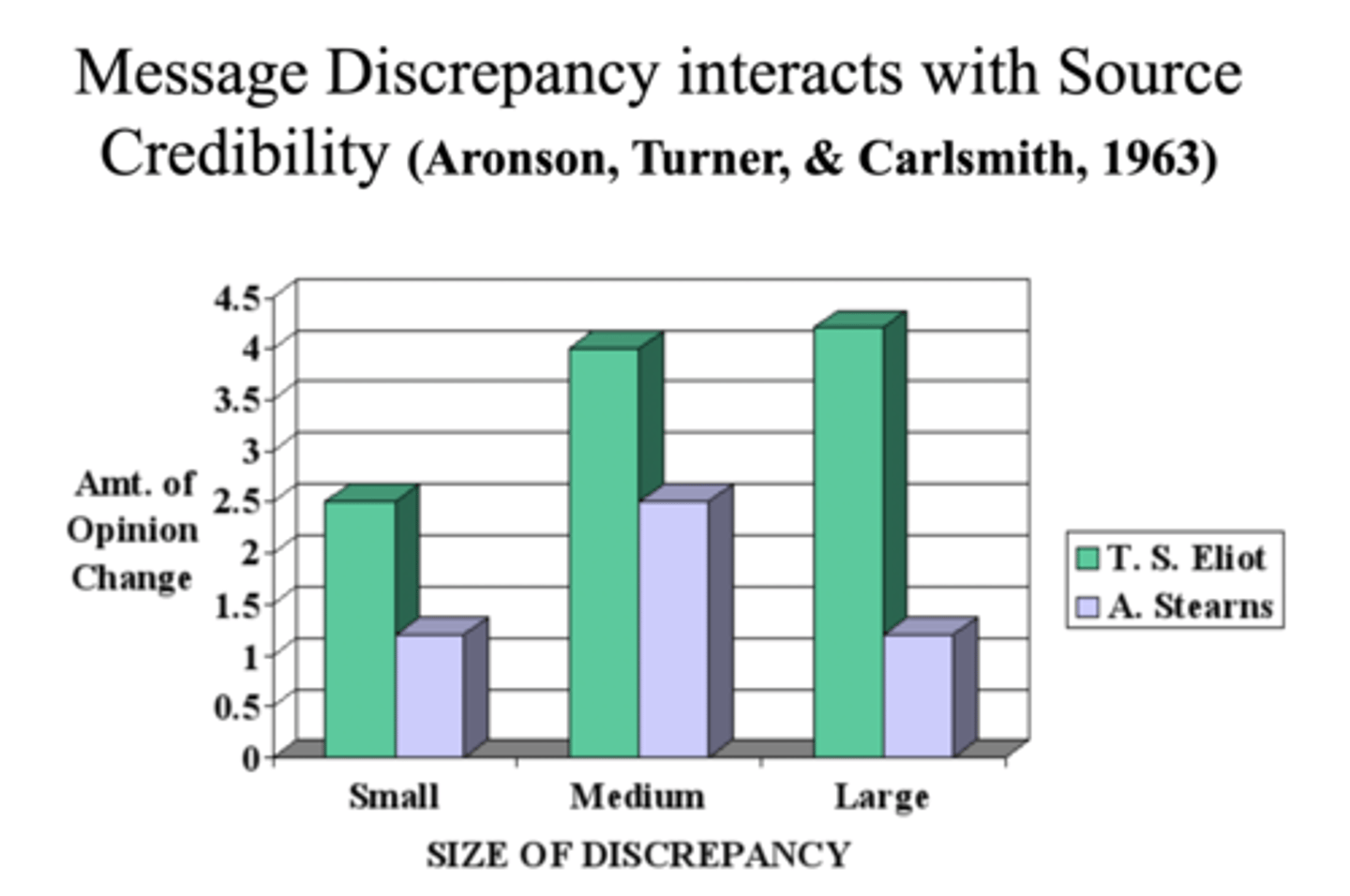

Source Credibility & Message Discrepancy (Aronson et al.)

The poems given to subjects were poor quality

Small Discrepancy: “Yes, the poem is mostly bad, but there might be a little potential—maybe with some practice, the writer could improve."

Medium Discrepancy: “It isn’t great in its current form, but it does show promise; with effort and polishing, it could be publishable.”

Large Discrepancy: “This poem is already a brilliant work of art—it should be published immediately with no changes.”

High-credibility T.S. Eliot persuaded people even with a large discrepancy message (because his expertise made the “leap” more acceptable).

Low-credibility A. Stearns did best only with a moderate discrepancy; a large discrepancy was rejected outright.

Again, this is an interaction: The effect message discrepancy depends on the credibility of the source.

Message Variables

Strength/Quality of Argument: How compelling or rational (with empirical evidence) is the persuasive message?

Strong = A lot of data and info; Weak = no info and common sense

When does it make a difference: In central route, it makes all the difference. In peripheral route, not so much.

EXCEPTION: Logical, informative messages will not work well when values and feelings are the basis of the attitude in question.

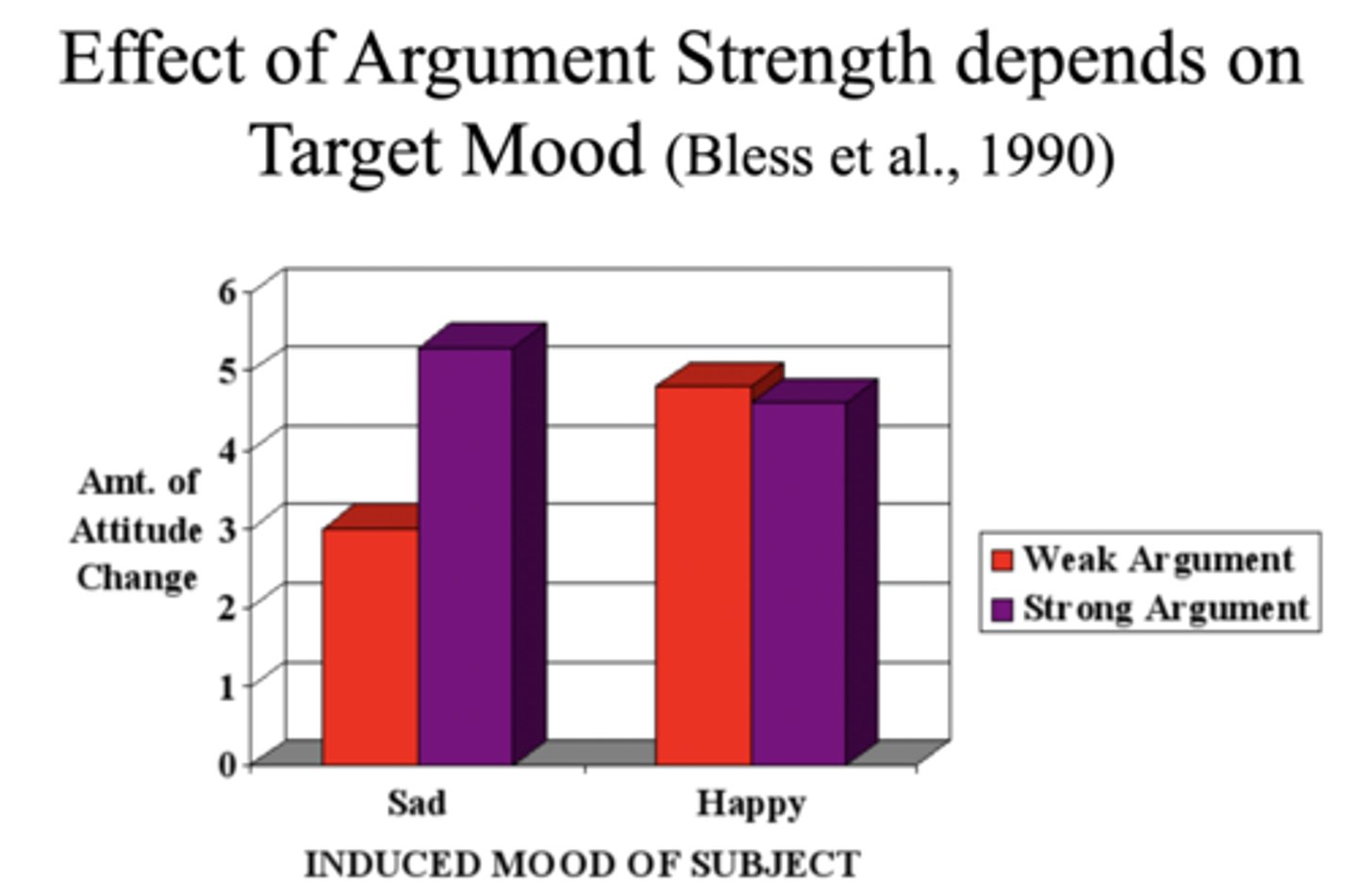

Target Mood, Bless et al. (1990)

A sad mood acts like a ‘caution light’—people think carefully (central route). They see a big difference between strong vs. weak arguments. A happy mood is a ‘green light’—peripheral route. They tend to be receptive no matter what, so argument quality matters less.

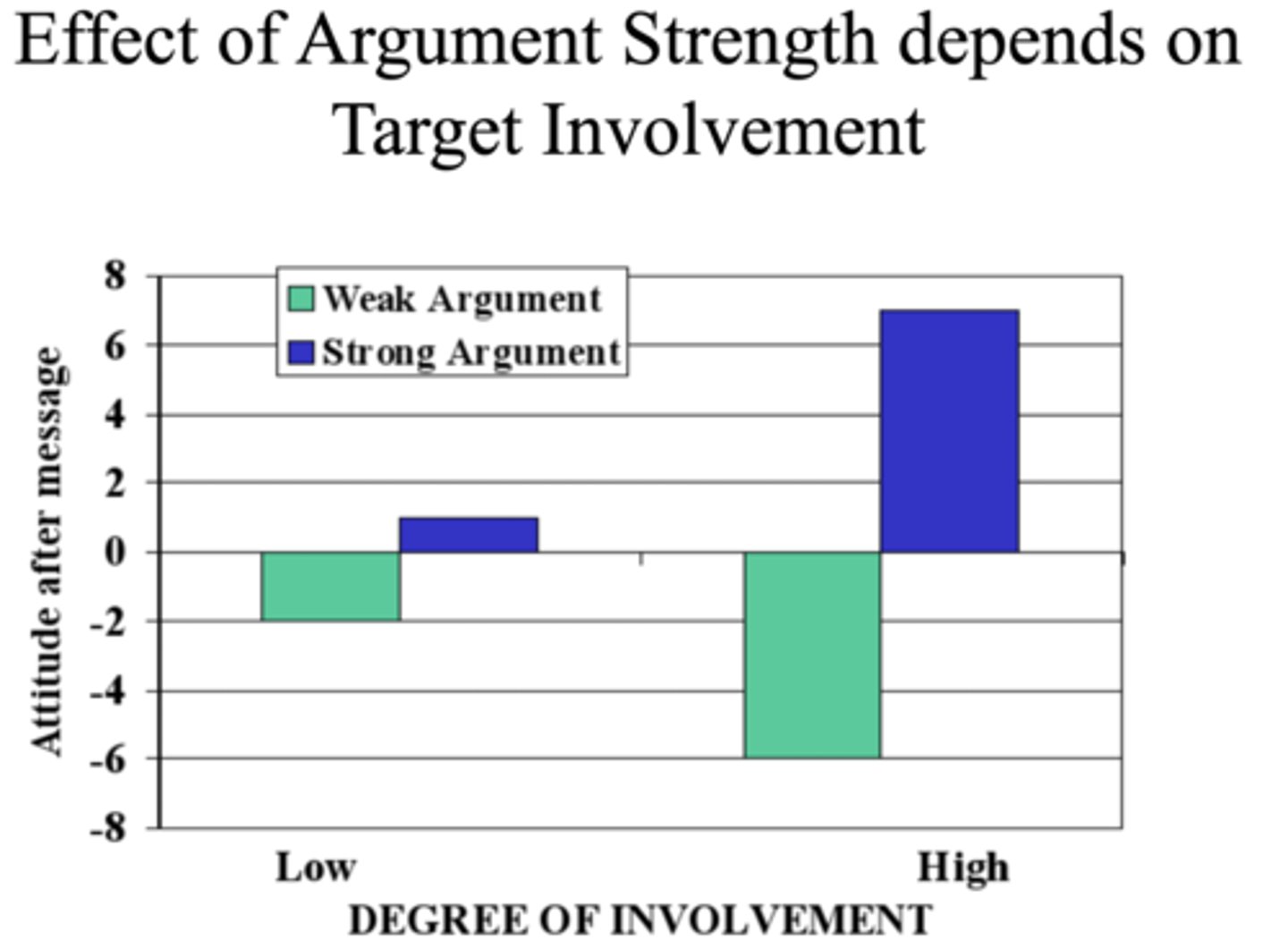

Argument Strength Depends on Target Involvement

Study: A policy about requiring a final exam (with a certain score) for the respective major before earning a degree.

Strong argument: Universities that require this exam have students that get into prestigious institutions and get higher salaries. The university gets promoted and students learn more.

Weak argument: Other universities do this, so let's do this too.

When people are highly involved—that is, the issue is personally relevant and important—they process the message via the central route.

Strong arguments greatly increase persuasion.

Weak arguments can backfire and produce strong resistance.

When people are low in involvement—it didn't make much of a difference—they rely on the peripheral route.

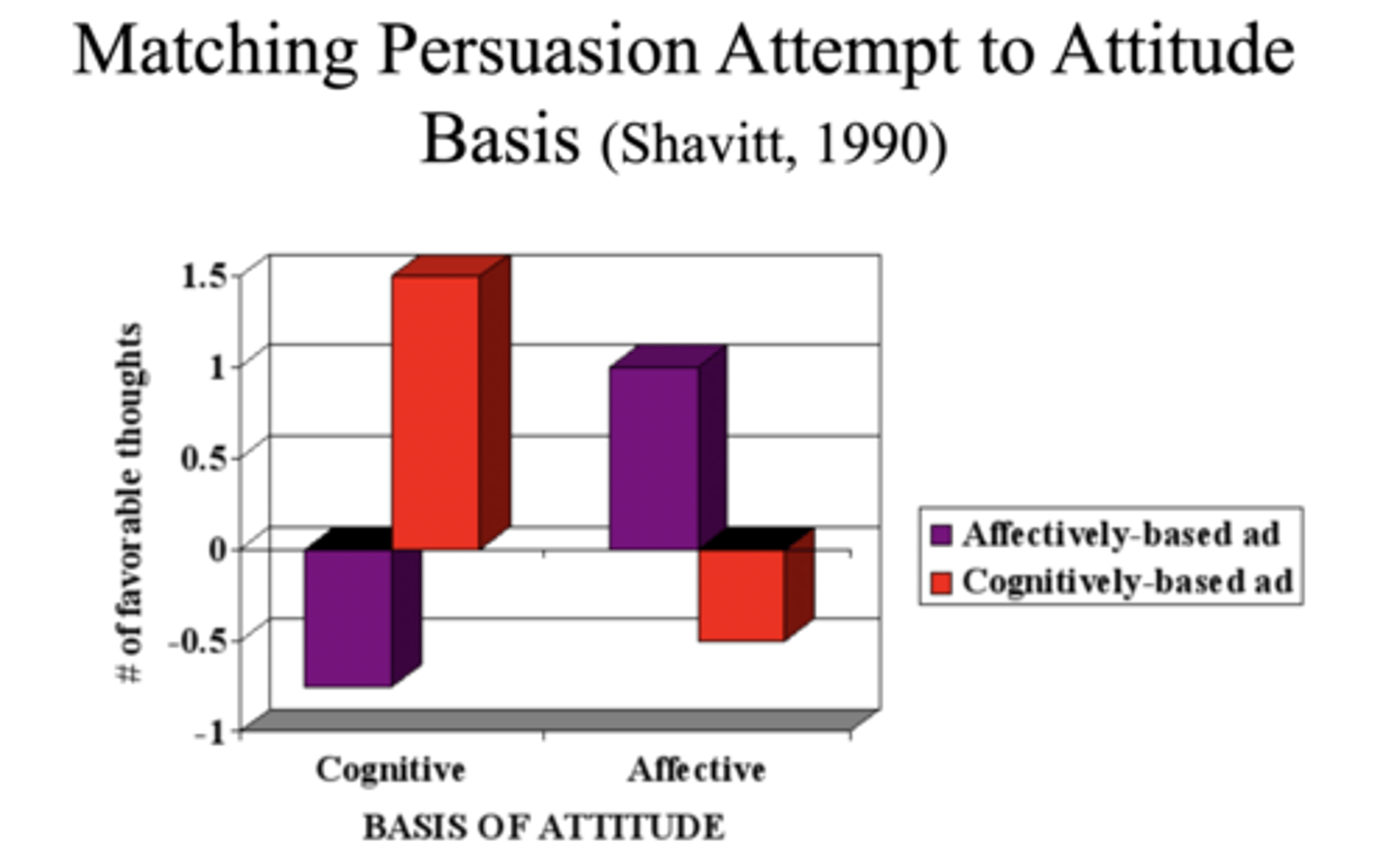

Effecting Attitude Change: Matching Persuasion Attempt to Attitude Basis

Cognitively-based attitudes need information—facts, data, quality arguments.

Affectively-based attitudes need emotional appeals—feelings, visuals, mood.

In Shavitt’s (1990) study, an affective ad worked for perfumes or fragrances but failed for a cognitively-based attitudes (chemicals of perfume), and vice versa.

Effecting Attitude Change: Psychological Reactance

Reactance is when people feel their freedom to choose is threatened, so they do the opposite of what’s demanded (rebellion).

The more heavy-handed the message (‘You must!’), the more reactance.

Pennebaker & Sanders (1978) found that a stern/serious demand sign (‘No writing, or else severe punishment!’) led to more graffiti than a polite request sign.

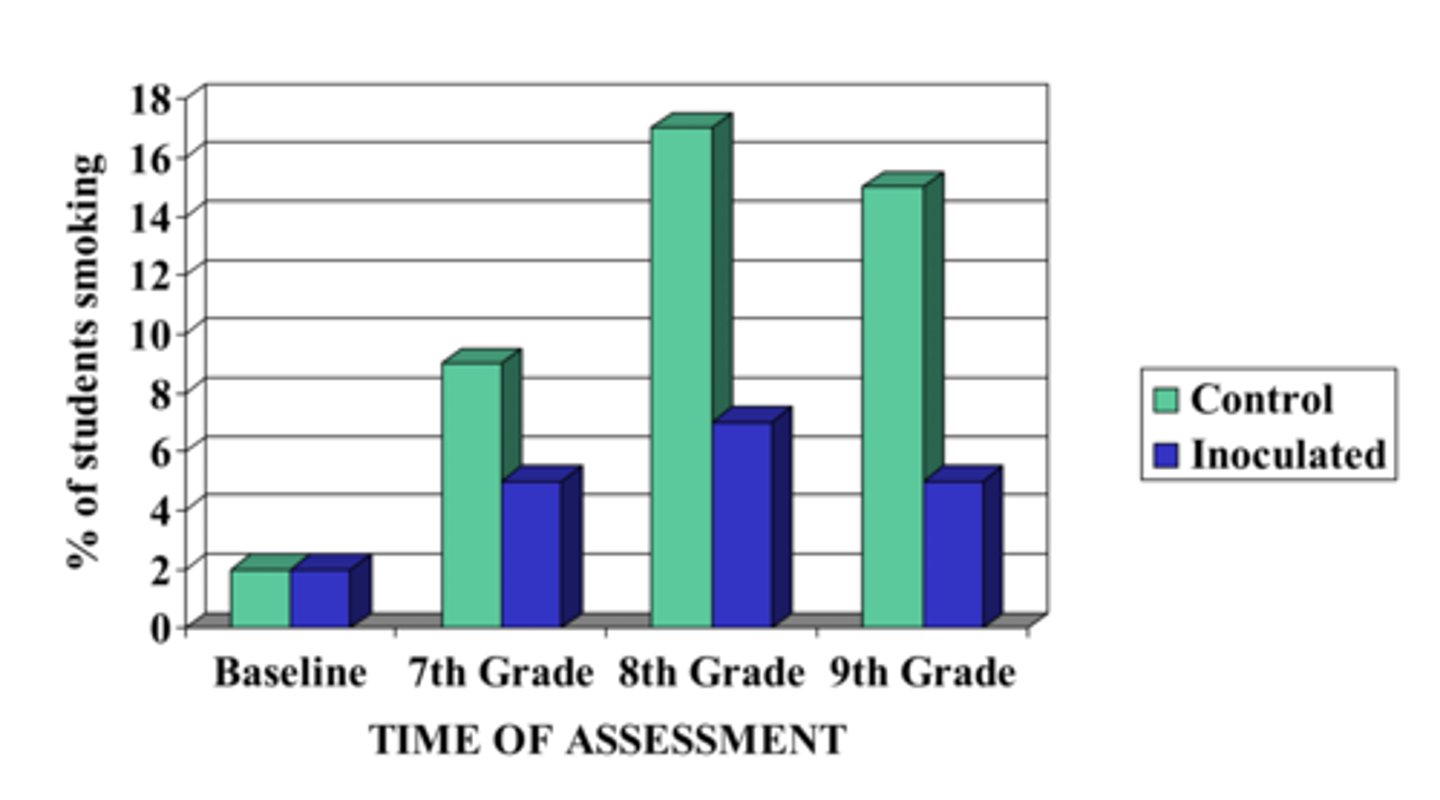

Effecting Attitude Change: Attitude Inoculation

Like a vaccine, you expose people to a weakened form of the opposing arguments, so they build up "counterargument antibodies."

In the smoking study:

Control group: Saw general anti-smoking info only.

Inoculated group: Practiced mock peer-pressure scenarios where kids tried to persuade them to smoke and learned how to refute it.

Inoculated students smoked less over time (7th–9th grade) because they were prepared to resist real peer pressure.

SUBLIMINAL PERSUASION: DOES IT WORK?

Only if it's immediately after.