Family Therapy - Chapter 2 Notes

1/93

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

94 Terms

Cybernetics

The study of feedback mechanisms in self-regulating systems.

feedback loop

the process by which a system gets the information necessary to maintain a steady course. This feedback includes information about the system’s performance and the relationship among the system’s parts.

Negative feedback

Negative feedback indicates that a system is straying off the mark and that corrections are needed to get it back on course. It signals the system to restore the status quo. Thus, negative feedback is not such a negative thing. Its error-correcting information gives order and self-control to automatic machines, to the body and the brain, and to people in their daily lives.

Positive feedback

reinforces the direction a system is taking.

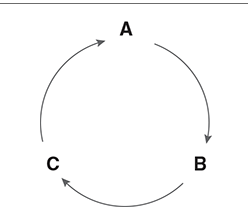

Circular Causality of a Feedback Loop

Thus A affects B, which in turn affects C, which feeds back to A, and so on.

runaway process

Like negative feedback, positive feedback can have desirable or undesirable consequences. If left unchecked, the reinforcing effects of positive feedback tend to compound a system’s errors, leading to a runaway process.

Cybernetics

was the brainchild of MIT mathematician Norbert Wiener (1948), who developed what was to become the first model of family dynamics in an unlikely setting. During World War II, Wiener was asked to design a better way to control the targeting of antiaircraft artillery (Conway & Siegelman, 2005).

As applied to families, cybernetics focused attention on:

(1) family rules, which govern the range of behavior a family system can tolerate (the family’s homeostatic range); (2) negative feedback mechanisms that families use to enforce those rules (guilt, punishment, symptoms); (3) sequences of interaction around a problem that characterize a system’s reaction to it (feedback loops); and (4) what happens when a system’s accustomed negative feedback is ineffective, triggering positive feedback loops.

self-fulfilling prophecy

is one such positive feedback loop; one’s apprehensions lead to actions that precipitate the feared situation, which in turn justifies one’s fears, and so on.

Another example of positive feedback is the bandwagon effect

the tendency of a cause to gain support simply because of its growing number of adherents.

One way out of an escalating feedback loop is disarmament.

Or one can simply refuse to compete. If one sibling pushes the other, the second sibling can simply refuse to push back—thereby stopping the process of escalation in its tracks. (But don’t hold your breath.)

Systems theory .

had its origins in the 1940s, when theoreticians began to construct models of the structure and functioning of mechanical and biological units

According to systems theory

the essential properties of a system arise from the relationship among its parts. These properties are lost when a system is reduced to isolated elements. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Thus, from a systems perspective, it would make little sense to try to understand a child’s behavior by interviewing him or her without the rest of the child’s family.

sequences of interaction

reveal how systems function

the “black box” metaphor:

A "black box" metaphor refers to a system where you can only observe the inputs and outputs, but the internal workings or processes happening within the system are completely unknown or hidden, like a literal black box where you can't see inside, making it impossible to understand how it produces its results; essentially, it's a system where you only know what goes in and what comes out, not how it transforms one into the other. “The impossibility of seeing the mind ‘at work’ has in recent years led to the adoption of the Black Box concept from telecommunication . . . applied to the fact that electronic hardware is by now so complex that it is sometimes more expedient to disregard the internal structure of a device and concentrate on the study of its specific input–output relations” (Watzlawick, Beavin, & Jackson, 1967, p. 43).

Among the features of systems seized on by early family therapists, few were more influential than homeostasis

the self-regulation that keeps systems stable. Don Jackson’s notion of family homeostasis emphasized that dysfunctional families’ tendency to resist change went a long way toward explaining why, despite heroic efforts to improve, so many patients remain stuck (Jackson, 1959).

general systems theory

In the 1940s, an Austrian biologist, Ludwig von Bertalanffy, attempted to combine concepts from systems thinking and biology into a universal theory of living systems—from the human mind to the global ecosphere. Starting with investigations of the endocrine system, he began extrapolating to more complex social systems and developed a model that came to be called general systems theory.

endocrine system

The endocrine system is a network of glands throughout the body that produce hormones, which are chemical messengers that travel through the bloodstream to regulate various bodily functions like growth, metabolism, reproduction, mood, and response to stress; essentially controlling many vital aspects of the body by sending hormonal signals to different organs and tissues.

Open systems

as opposed to closed systems (e.g., machines), sustain themselves by exchanging resources with their environment—for example, taking in oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide.

To summarize, Bertalanffy brought up many of the issues that have shaped family therapy:

• A system as more than the sum of its parts

• Emphasis on interaction within and among systems versus reductionism

• Human systems as ecological organisms versus mechanism

• Concept of equifinality

• Homeostatic reactivity versus spontaneous activity

Equifinality

is the idea that a given outcome can be achieved in multiple ways

morphogenesis

Walter Buckley (1968) coined the term morphogenesis to describe this plastic quality of adaptive systems.

Social Constructionism

Systems theory taught us to see how people’s lives are shaped by their interactions with those around them. But in focusing on behavior, systems theory left something out—actually, two things: how family members’ beliefs affect their actions, and how cultural forces shape those beliefs.

Constructivism

Constructivism captured the imagination of family therapists in the 1980s, when studies of brain function showed that we can never really know the world as it exists out there; all we can know is our subjective experience of it. Research on neural nets (von Foerster, 1981) and the vision of frogs (Maturana & Varela, 1980) indicated that the brain doesn’t process images literally, like a camera, but rather registers experience in patterns organized by the nervous system.1 Nothing is perceived directly. Everything is filtered through the mind of the observer.

Constructivism

Constructivism is the modern expression of a philosophical tradition that goes back as far as the eighteenth century. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) regarded knowledge as a product of the way our imaginations are organized. The outside world doesn’t simply impress itself onto the tabula rasa (blank slate) of our minds, as British Empiricist John Locke (1632–1704) believed. In fact, as Kant argued, our minds are anything but blank. They are active filters through which we process and interpret the world

Constructivism found its way into psychotherapy in the personal construct theory of George Kelly (1955).

According to Kelly, we make sense of the world by creating our own constructs of the environment. We interpret and organize events, and we make predictions that guide our actions on the basis of these constructs. You might compare this to seeing the world through a pair of eyeglasses. Because we may need to adjust constructs, therapy became a matter of revising old constructs and developing new ones—trying on different lenses to see which ones enable us to navigate the world in more satisfying ways.

reframing

The first application of constructivism in family therapy was the technique of reframing—relabeling behavior to shift how family members respond to it.

Systems metaphors focused on behavior; constructivism shifted the focus to the assumptions people have about their problems.

The goal of therapy changed from interrupting problematic patterns of interaction to helping clients find new perspectives on their lives.

Constructivism teaches us

to look beyond behavior to the ways we interpret our experience. In a world where all truth is relative, the perspective of the therapist has no more claim to objectivity than that of the clients. Thus constructivism undermined the status of the therapist as an impartial authority with privileged knowledge of cause and cure. It’s probably well to remember that even our most cherished metaphors of family life—system, enmeshment, dirty games, triangles, and so on—are just that: metaphors. They don’t exist in some objective reality; they are constructions, some more useful than others.

Dirty Games

The concept of "dirty games" (or "games" in transactional analysis) refers to manipulative, indirect, or covert behavior that people use to meet their psychological needs without being open and honest. These are often unconscious and can be damaging to relationships. In the context of family or interpersonal relationships, dirty games might involve playing one person against another, guilt-tripping, passive-aggressive behavior, or using manipulation to avoid direct communication. People involved in dirty games are often trying to achieve a goal (like control or validation) but do so in ways that are deceptive, harmful, or underhanded.

Enmeshment

Enmeshment refers to a relationship dynamic where boundaries between individuals (often within a family) are overly blurred, leading to an excessive emotional involvement or over-dependence. In an enmeshed system, family members (or individuals) may lack clear personal boundaries, and there can be an unhealthy level of emotional entanglement. This often prevents members from developing healthy, independent identities. Enmeshment can limit emotional autonomy and may lead to difficulties in establishing appropriate distance or boundaries in relationships.

Triangles

In family systems theory, a triangle refers to a three-person relationship dynamic that often arises when two people in a system (like a family) have unresolved issues, and one of them brings in a third person to stabilize or distract from the conflict. Triangles are typically seen as an unhealthy way to manage tension, as they avoid directly addressing the problem between the two main individuals. For example, in a family, a parent may involve a child in their marital conflict, thus creating a triangle where the child may feel forced to take sides, or they may act as a "buffer" between the two parents. These triangles can perpetuate dysfunctional patterns and prevent the core issues from being resolved.

System

In psychology, especially within systems theory, the term system refers to an interconnected group of elements that influence each other and function together as a whole. This can apply to families, organizations, or any network of relationships. A system is not just a collection of individuals, but rather a dynamic whole where changes in one part of the system affect the entire system. For example, in family systems theory, the family unit is seen as a system where each member’s behavior influences and is influenced by others in the family.

idiosyncratic perspective

refers to a way of thinking or viewing the world that is unique or specific to an individual.

solipsistic streak

A solipsistic streak refers to a tendency or inclination to view the world primarily from one's own perspective, often to the exclusion or disregard of others' viewpoints or experiences. Solipsism is a philosophical concept that suggests that only one's own mind and experiences can be known to exist with certainty, and everything else, including other people and the external world, might be perceived as projections or constructs of the self.

Once that solipsistic streak was pointed out

leading constructivists clarified their position: When they said that reality was constructed, they meant socially constructed.

Social constructionism

Social constructionism expanded constructivism much as family therapy expanded individual psychology. Constructivism says that we relate to the world on the basis of our own interpretations. Social constructionism points out that those interpretations are shaped by our context.

communications scholar Joshua Meyrowitz (1985) said more than 30 years ago in No Sense of Place is even more true now:

Today’s children are exposed to the “back stage” of the adult world, to otherwise hidden doubts and conflicts, foolishness and failures of adult types they see on TV. This demystification undermines adolescent trust in traditional authority structures. It’s hard to respect adult wisdom when your image of a parent is Homer Simpson.

Both constructivism and social constructionism

focus on interpretation of experience as a mediator of behavior. But while constructivists emphasized the subjective mind of the individual, social constructionists place more emphasis on the intersubjective influence of language and culture (Lock & Strong, 2010). According to constructivism, people have problems not merely because of the objective conditions of their lives but also because of their interpretation of those conditions. What social constructionism adds is a recognition of how such assumptions emerge in the process of talking with other people.

Deconstruction

freeing clients from the tyranny of entrenched beliefs. How this plays out in practice is illustrated in two of the most influential new versions of family therapy: solution-focused therapy and narrative therapy.

Solution-focused therapy

Inherent in most forms of therapy is the idea that before you can solve a problem, you must figure out what’s wrong. This notion seems self-evident, but it’s a construction—one way of looking at things. Solution-focused therapy turns this assumption on its head, using a totally different construction—namely, that the best way to solve problems is to discover what people do when they’re not having the problem.

Like their solution-focused colleagues, narrative therapists create a shift in their clients’ experience by

helping them reexamine how they look at things. But whereas solution-focused therapy shifts attention from current failures to past successes in order to mobilize behavioral solutions, narrative therapy’s aim is broader and more attitudinal. The decisive technique in this approach—externalization—involves the truly radical reconstruction of defining problems not as properties of the individuals who suffer them but as alien oppressors. Thus, for example, while the parents of a boy who doesn’t keep up with his homework might define him as lazy or a procrastinator, a narrative therapist would talk instead about times when “Procrastination” gets the better of him—and times when “It” doesn’t.

Externalization

Externalization is a psychological concept that involves attributing one's thoughts, feelings, or problems to external factors, forces, or entities, rather than seeing them as originating from within oneself. It can be a defense mechanism, a way for individuals to avoid personal responsibility, or a way to cope with difficult emotions or situations.

Externalization allows a person to distance themselves from difficult emotions, conflicts, or behaviors by externalizing them, making them feel like something "out there" rather than an intrinsic part of themselves. This can sometimes provide temporary relief or a sense of control, but it can also lead to unhealthy coping patterns or avoidant behavior.

In emotionally focused couples therapy

Susan Johnson uses attachment theory to deconstruct the familiar dynamic in which one partner criticizes and complains while the other gets defensive and withdraws. What attachment theory suggests is that the criticism and complaining are protests against disruption of the attachment bond—in other words, the nagging partner may be more insecure than angry.

In the 1940s and 1950s, a number of studies found that young children who were separated from their mothers go through a series of reactions that can be described

As protest, despair, and finally detachment — In attempting to understand these reactions, Bowlby (1958) concluded that the bond between infants and their parents was based on a biological drive for proximity that evolved through the process of natural selection. When danger threatens, infants who stay close to their parents are less likely to be killed by predators. Bowlby called this bond “attachment.”

Attachment means

seeking closeness in the face of stress. Attachment can be seen in cuddling up to Mother’s warm body and being cuddled in return, looking into her eyes and being looked at fondly, and holding on to her and being held. These experiences are profoundly comforting.

secure attachment

The child who has secure attachment experiences will develop a sense of basic security and will not be subject to morbid fears of being helpless, abandoned, and alone in the world. When threats arise, infants in secure relationships are able to direct attachment behavior (approaching, crying, reaching out) to their caregivers and take comfort in their reassurance (Bowlby, 1988). Infants with secure attachments are confident in the availability of their caregivers and, consequently, confident in their interactions in the world.

Insecure attachment

poisons a child’s self-confidence. that child develops a sense of shame around those needs; such children doubt the validity of their needs and feel bad for having them. They also come to believe that others cannot be depended on. They develop an insecure attachment (Bowlby, 1988). Insecure attachment generally falls into two categories: anxious and avoidant.

If a child’s caregivers are generally unavailable or unresponsive to the child’s needs

that child develops a sense of shame around those needs; such children doubt the validity of their needs and feel bad for having them. They also come to believe that others cannot be depended on. They develop an insecure attachment (Bowlby, 1988). Insecure attachment generally falls into two categories: anxious and avoidant.

Anxiously attached children

tend to have overprotective and intrusive parents. These children learn that the validity of their needs must be approved by their caregivers. As a result, over time, these children find it increasingly difficult to identify what they truly feel. Anxiously attached children cling to their caregivers; the message from the caregivers’ intrusiveness is that the world is a dangerous place—you need me to manage it (Ainsworth, 1967). As an adult, anxiously attached individuals often suffer from depression and anxiety as they habitually give in to others’ demands and work hard to please people. When their emotional security is threatened in adult romantic relationships, anxiously attached individuals will disregard their own needs as they try to restore a comfortable level of emotional closeness by frantically pulling their partner closer out of fear of losing them (Bowlby, 1973). Fear of abandonment—“terror” might be the better term in order to convey how all-consuming it is—haunts some people like nothing else.

Avoidantly attached children

tend to have emotionally unavailable parents. The child will make initial attempts at seeking comfort from his or her caregiver, but when it becomes apparent that the caregiver will not respond, the child eventually gives up. A similar pattern happens with exploring—the child may start to venture out but often gives up when faced with challenges (Ainsworth, 1967). These children learn that others will not be responsive to their needs, and in an attempt to avoid the pain of rejection, they try to cut off or otherwise not feel those unmet needs. When faced with insecurity in their intimate attachment relationships, avoidantly attached adults will often become distant and aloof in an effort to not need their partners and therefore not feel hurt by their rejection (Bowlby, 1973).

One of the things that distinguishes attachment theory

is that it has been extensively studied. What is clear is that it is a stable and influential trait throughout childhood. The type of attachment shown at 12 months predicts: (1) type of attachment at 18 months (Main & Weston, 1981; Waters, 1978); (2) frustratability, persistence, cooperativeness, and task enthusiasm at 18 months (Main, 1977; Matas, Arend, & Sroufe, 1978); (3) social competence of preschoolers (Lieberman, 1977; Waters, Wippman, & Sroufe, 1979); and (4) self-esteem, empathy, and classroom deportment (Sroufe, 1979). The quality of relationship at one year is an excellent predictor of quality of relating up through five years, with the advantage to the securely attached infant.

What is less clearly supported by research is the proposition that styles of attachment in childhood

are correlated with attachment styles in adult relationships. Nevertheless, the idea that romantic love can be conceptualized as an attachment process (Hazan & Shaver, 1987) remains a compelling if as yet unproven proposition. What the research has established is that individuals who are anxious over relationships report more relationship conflict, suggesting that some of this conflict is driven by basic insecurities over love, loss, and abandonment. Those who are anxious about their relationships often engage in coercive and distrusting ways of dealing with conflict, which are likely to bring about the very outcomes they fear most (Feeney, 1995).

attachment theory offers a deeper understanding of

the dynamics of familiar interactional problems. For example, a common pursue/withdraw pattern emerges when an anxiously attached partner pursues closeness while an avoidantly attached partner withdraws emotionally. Even though the underlying motivation for each partner is to establish emotional safety and closeness, their attachment fears of rejection lead them to act in a way that pushes their partner away, thus giving each of them less of what they long for (Johnson, 2002). Their solution has become the problem.

The fundamental premise of family therapy is

that people are products of their context. Because few people are closer to us than our parents and partners, this notion can be translated into saying that a person’s behavior is powerfully influenced by interactions with other family members. Thus the importance of context can be reduced to the importance of family. It can, but it shouldn’t be.

Although the family is often the most relevant context for understanding behavior, it isn’t always.

A depressed college student, for example, might be more unhappy about what’s going on in the dormitory than about what’s happening at home.

The clinical significance of context is

that attempts to treat individuals by talking to them once a week may have less influence than their interactions during the remaining 167 hours of the week. Or to put this positively, often the most effective way to help people resolve their problems is to meet with them together with important others in their lives.

Complementarity refers to

the reciprocity that is the defining feature of every relationship. In any relationship one person’s behavior is yoked to the other’s. Remember the symbol for yin and yang, the masculine and feminine forces in the universe.

Complementarity doesn’t mean

that people in relationships control each other; it means that they influence each other.

Before the advent of family therapy, explanations of psychopathology were based on linear models:

medical, psychodynamic, or behavioral. Etiology was conceived in terms of prior events—disease, emotional conflict, or learning history. With the concept of circularity, Bateson helped change the way we think about psychopathology, from something caused by events in the past to something that is part of ongoing, circular feedback loops.

Linear models

refer to frameworks that seek to explain phenomena through straightforward, cause-and-effect relationships, typically assuming that one factor leads directly to another in a predictable sequence.

Medical Model (Linear Causality in Medicine)

The medical model is grounded in the assumption that physical and psychological problems are caused by identifiable, biological or physiological factors. In a linear sense, this model tends to view mental health or physical issues as resulting from a specific cause (e.g., an infection, injury, or chemical imbalance) that can be identified, diagnosed, and treated.

Psychodynamic Model (Linear Causality in Psychoanalysis)

The psychodynamic model (rooted in Freudian psychoanalysis and later developments) views mental health issues as stemming from unconscious conflicts, early life experiences, and unresolved psychological issues. While more complex than the medical model, it still follows a linear approach in the sense that specific unconscious factors (such as repressed memories, conflicts, or early trauma) are seen as causing present psychological symptoms or disorders.

Behavioral Model (Linear Causality in Behavioral Psychology)

The behavioral model focuses on observable behaviors and the environmental factors that shape them. According to this model, problematic behaviors are learned through conditioning (classical or operant) and can be unlearned or modified by changing the environmental stimuli that reinforce or trigger them. This approach operates on a more concrete, linear cause-and-effect basis.

Classical conditioning and operant conditioning are

both types of learning processes that are central to behavioral psychology. While they both involve learning through association and experience, they differ in terms of how behaviors are acquired and the mechanisms that drive this learning.

Classical Conditioning (Pavlovian Conditioning)

Classical conditioning was first described by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov. It involves learning through association, where a natural, reflexive response to one stimulus becomes triggered by a different, initially neutral stimulus after the two stimuli are repeatedly paired together.This process is exemplified by Pavlov's experiments with dogs, where the sound of a bell became associated with food, causing the dogs to salivate at the sound alone.

Operant Conditioning (Instrumental Conditioning)

Operant conditioning, a concept developed by B.F. Skinner, involves learning through consequences (reinforcements or punishments) following voluntary behaviors. It’s a form of associative learning, but instead of associating two stimuli, the organism learns to associate a behavior with its consequences.

Etiology

the cause, set of causes, or manner of causation of a disease or condition.

The notion of linear causality is based on

the Newtonian model in which the universe is like a billiard table where the balls act unidirectionally on each other. Bateson believed that while linear causality is useful for describing the world of objects, it’s a poor model for the world of living things because it neglects to account for communication and mutual influence.

This idea of mutual or circular causality is

enormously useful for therapists because so many families come in looking to find the cause of their problems and determine who is responsible. Instead of joining the family in a logical but unproductive search for who started what, circular causality suggests that problems are sustained by an ongoing series of actions and reactions.

Process/Content

Focusing on the process of communication (how people talk), rather than its content (what they talk about), may be the single most productive shift a family therapist can make.

structure

defines the organization within which those interactions take place. Initially, interactions shape structure; but once established, structure shapes interactions.

Families are structured in subsystems

determined by generation, gender, and function—which are demarcated by interpersonal boundaries, invisible barriers that regulate the amount of contact with others (Minuchin, 1974).

boundaries safeguard

the integrity of the family and its subsystems. By spending time alone together and excluding friends and family from some of their activities, a couple establishes a boundary that protects their relationship from intrusion.

Psychoanalytic theory

emphasizes the need for interpersonal boundaries. Beginning with “the psychological birth of the human infant” (Mahler, Pine, & Bergman, 1975), psychoanalysts describe the progressive separation and individuation that culminates in the resolution of oedipal attachments and eventually in leaving home.

oedipal attachments

Oedipal attachment is a child's emotional attachment to their opposite-sex parent, along with feelings of rivalry and hostility towards their same-sex parent.This complex typically emerges during the phallic stage of development, as described by Freud, and plays a crucial role in the child's psychological development.

the Oedipus complex

In classical psychoanalytic theory, the Oedipus complex (also spelled Œdipus complex) refers to a son's sexual attitude towards his mother and concomitant hostility toward his father

family therapists discovered that problems result when boundaries

are either too rigid or too diffuse. Rigid boundaries permit little contact with outside systems, resulting in disengagement. Disengagement leaves people independent but isolated; it fosters autonomy but limits affection and nurture. Enmeshed subsystems have diffuse boundaries: They offer access to support but at the expense of independence. Enmeshed parents are loving and attentive; however, their children tend to be dependent and may have trouble relating to people outside their family. Enmeshed parents respond too quickly to their children; disengaged parents respond too slowly.

Interest in family narrative has become identified with one particular school

Michael White’s narrative therapy, which emphasizes the fact that families with problems come to therapy with defeatist narratives that tend to keep them from acting effectively. But a sensitivity to the importance of personal narrative is a useful part of any therapist’s work. However much a therapist may be interested in the process of interaction or the structure of family relationships, she or he must also learn to respect the influence of how family members experience events—including the therapist’s input.

the reproduction of mothering

As long as society expects the primary parenting to be done by mothers, girls will shape their identities in relation to someone they expect to be like, while boys will respond to their difference as a motive for separating from their mothers. The result is what Nancy Chodorow (1978) called “the reproduction of mothering.”