infection and the immune system

1/31

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

32 Terms

Pathogens

microorganisms / infectious agents that cause disease

different forms of microorganisms / infectious agents

viruses

bacteria

fungi/yeast

protozoa

helminths

prions

how do we acquire infections?

transmission can be by physical contact, ingestion, inhalation, via vectors or breaching skin defences

microorganisms exploit mucosal sites (respiratory, gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts) for transmission

the skin acts as a barrier. breaches (abrasions, cuts) can make the host vulnerable to infection. biting insects can acts as vectors for disease transmission by bypassing the skin defence barrier.

mucosal immunity is highly specialised and very important for protection against infection, developing mucosal vaccines has been challenging

what makes microorganisms harmful?

a combination of factors, some of which are microbe-specific (virulence factors), others are host-specific (inflammation)

microorganisms evolve and adapt to their hosts and vice-versa. such adaptations can be site-specific and/or host specific (intra-host or inter-host)

intra-host

the immune system might ‘ignore’ microorganisms at one anatomical site, but react to them at another.

e.g. commensals ignored in the gut, but stimulate very strong inflammatory immune responses if they spread to other anatomical locations (ruptures of the gut wall)

inter-host

microorganisms that cross species barriers may not produce disease in one host but can in another and even be lethal

inter-species transmission: zoonotic infections

humans and animals share common ecosystems hence their health is intrinsically linked (One health). this provides opportunities for infections to spread from animals to humans (zoonoses) and vice-versa (reverse zoonoses).

this can occur via ingestion, physical contact, aerosols, environmental contamination.

when pathogens jump species barriers to establish infections in different hosts, the outcome is unpredictable

evolutionary host-pathogen adaptations

bats have constitutive interferon activity that suppresses viral infections (innate immunity)

bats also have unusually large naive antibody repertoires which dont require rapid affinity maturation for limiting viral replication (adaptive immunity)

selective pressures and transmission opportunities determine the survival and expansions of virus mutations. mutations selected for in one host species can have implications for disease pathogenesis in a different species

host adaptation of viruses

virus mutations are randome and can enhance transmission, virulence or immune evasion, depending on selective pressures and opportunities (including human behaviours). effective surveillance is key to protecting public health in a globalised society

CFRs - case fatality ratio

most CFRs are estimates. they depend on methods used to record deaths and the strategies for diagnosing infection rates within the population

CFRs can influence perceptions of risk versus hazard

individual human behaviours then impact on disease transmission and uptake of control strategies such as vaccination which subsequently affect populations

lessons from smallpox vaccine

success with smallpox vaccination was due in part to the efficacy of the vaccine at inducing herd immunity and to the fact that variola virus can only infect humans (there is no animal reservoir) - pathogen dependence on a single host is a potential achilles heel

using microorganisms for vaccination - benefits and risks

live-attenuated vaccines usually work well because they induce strong immunity, but they carry the risk due to their live nature, particularly for immuno-compromised individuals

dead or subunit vaccines (using part of the microorganism) are usually safer, but often dont work as well as live-attenuated vaccines, require effective adjuvants to stimulate strong protective immunity

we can genetically engineer ‘benign’ microorganisms to deliver a component of a disease-causing microorganism for vaccine-induced protection: viral vectors

co-evolution with microorganisms

our immune system expects to be challenged and may become dysregulated if not exposed to microorganisms

it might not be the presence of microorganisms but their absence thats cause disease

microbial flora

antibiotics have saved countess lives but need to be used carefully (antimicrobial resistance)

disrupting the natural microbial flora with antibiotics can lead to opportunistic yeast and fungal infections

roles of the immune system

controlling infections

killing tumours

immune pathology

graft rejection

metabolic diseases

what is the immune system?

a range of cells working together as a team

the immune challenges

detect a vast array of different pathogens

distinguish between harmful (pathogens) and harmless (food, pollen) exposures

respond rapidly and eliminate invading pathogens using the appropriate killing mechanism

control the strength of the response to limit immune-mediated damage

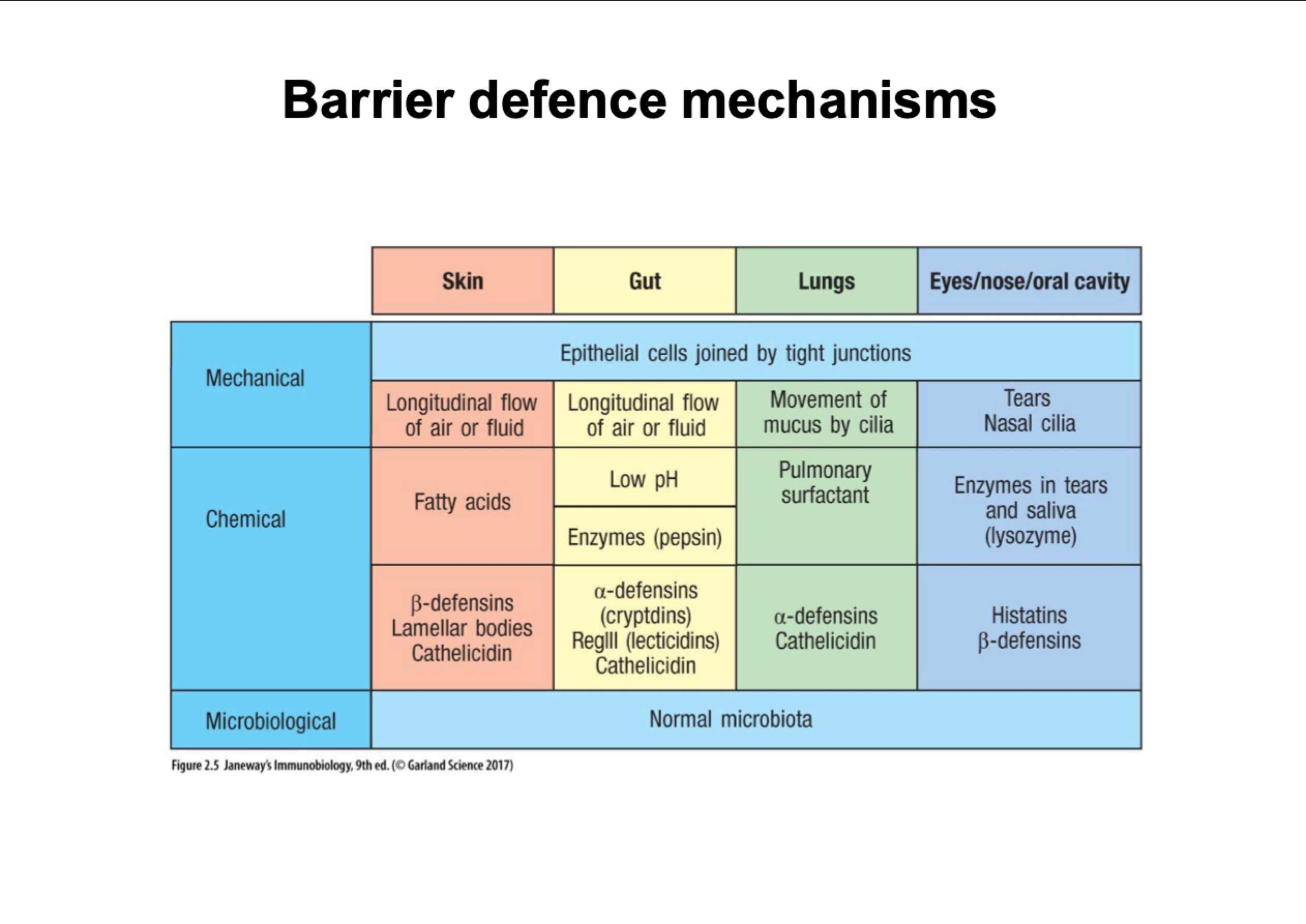

barrier defence mechanisms

tight junctions stop things getting between cells

cilia waft upwards, pushes anything that gets in lungs

stomach low ph, acid destroys bacteria

tears have lysozymes that break down bacterial cell walls

how do pathogens penetrates the barriers

skin breaks, wounds/burns

animal bites

insect bites

parasites burrow through skin

mucosal barriers

placenta

lungs

STDs

faecal-oral

food

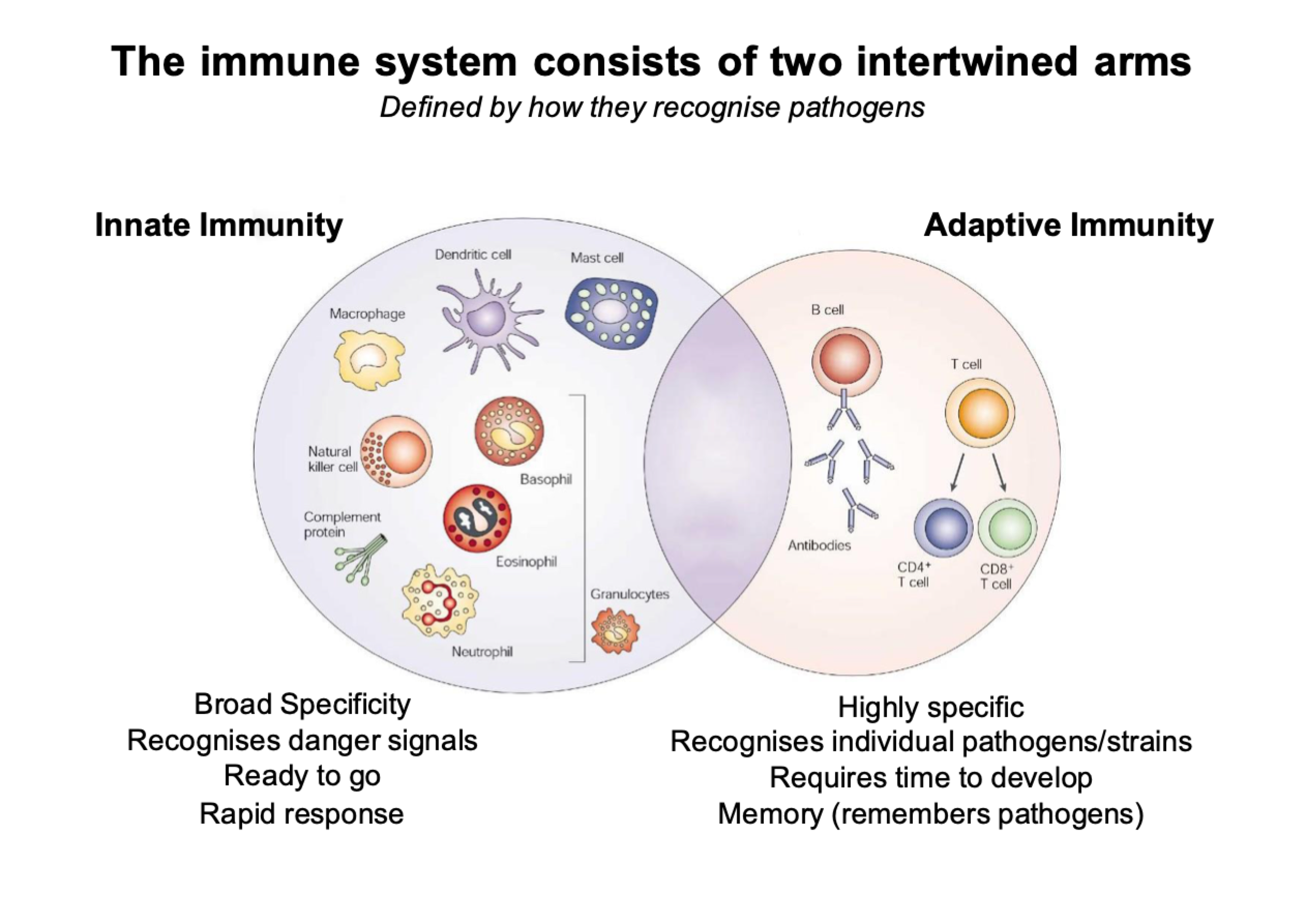

innate and adaptive immunity

the immune system consists of two intertwined arms

innate immunity is our first line of defence:

broad specificity

receptor recognise danger signals

rapids responses

can tell the class or type of virus

buys time until adaptive response kicks in

innate cells kick in first then works in partnership with adaptive cells

Adaptive immunity:

highly specific

recognises individual pathogens/strains

requires time to develop

memory (remembers pathogens)

B and T cells

slow

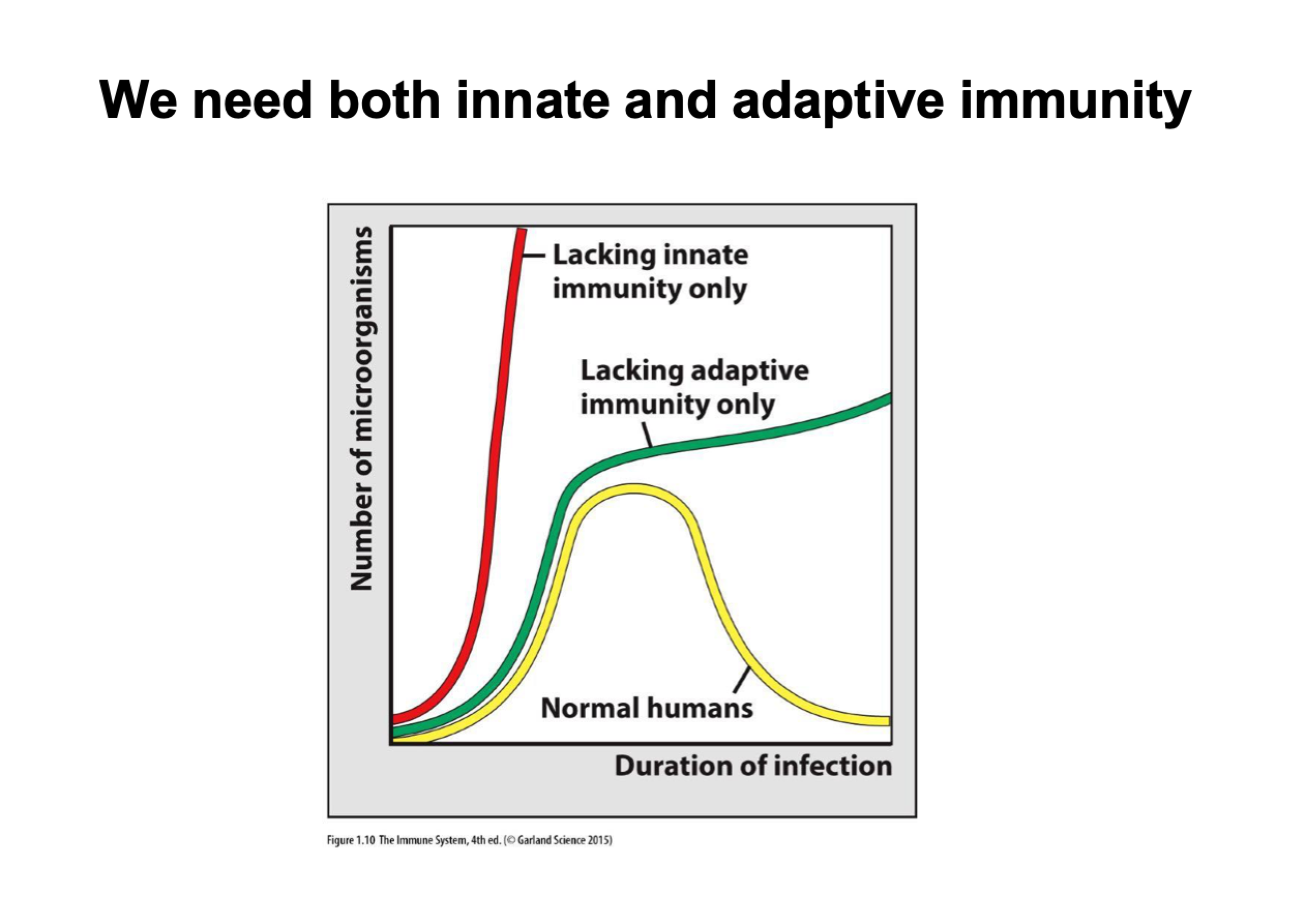

necessity of innate and adaptive immunity

we need both innate and adaptive immunity

absence of innate immunity - die quickly as theres nothing to respond to infection

absence of adaptive immunity - might be fine if infection dose is low, higher dosage of infection will result in death

functions if innate immunity

senses and responds to danger signals (infection & damage)

always on, always ready to respond instantly

communicates danger to other cells of innate and adaptive immunity

recruits immune cells to infection site (inflammation)

tells adaptive immune cells when to respond

cellular and biochemical killing mechanisms

innate killing mechanisms

phagocytosis - engulf bacteria and digest

killing of infected cells - NK cells identify infector or tumour, cells tell them to commit apoptosis

secretion of cytotoxic granules - fired out to microbes and kills them

complement proteins - punches holes causing them to explode

adaptive immunity

adaptive immunity consists of T cells and B cells

T and B cells can recognise a huge range of proteins and molecules (called antigens) with a high degree of specificity

their specificity for the pathogen makes the immune response more effective

identifying and expanding the T and B cells that recognise the pathogen takes time, which is why adaptive immunity is slow

T and B cells can remember previous encounters with pathogens (immune memory)

3 types of T cell

helper T cells (Th cell):

coordinate immune responses

amplifies innate immunity

talks to other cells

regulatory T cells (Treg cells):

turn-off immune responses

counter part to helper cells, turns off immune responses when not needed

cytotoxic T cells (CTL):

kill infected cells

B cells

B cells produce antibodies that:

are highly specific to individual pathogens

neutralise pathogen molecules e.g. toxins

mark pathogens for destruction by other immune cells

link innate and adaptive killing mechanisms

immune memory

adaptive memory is specific to the original pathogen

adaptive memory responses are faster and bigger

adaptive memory combines specificity with speed

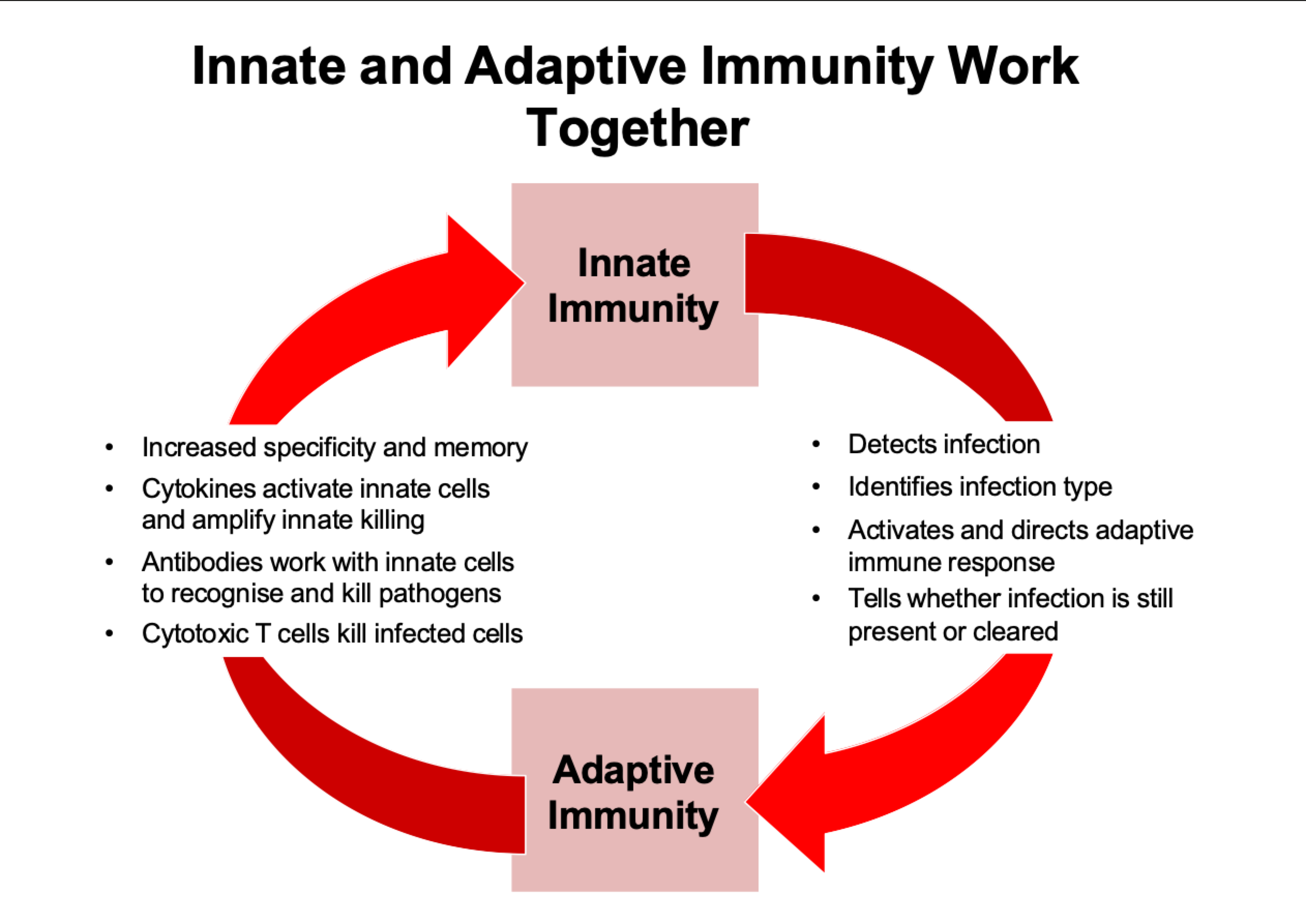

innate and adaptive immunity work together

cytokines

cytokines are chemical messengers (like hormones)

many different cytokines with different functions

target any cells with relevant receptor

allow one cell to signal to many cells

cells dont need to be in contact

can act locally or systematically

cell to cell communication

use receptor/ligand pairs on cell surface

many different receptors and ligands with different functions

cells have to be in contact and have correct receptor/ligand pairs

allows very precise communication between individual cells

lymph nodes and spleen

specialised sites where immune responses are coordinated

focal points for immune cell communication

play a very important role in initiating adaptive immune responses