CELL CYCLE AND CELL DIVISON

1/52

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

53 Terms

HOW DO PROKARYOTIC AND EUKARYOTIC CELLS DIVIDE?

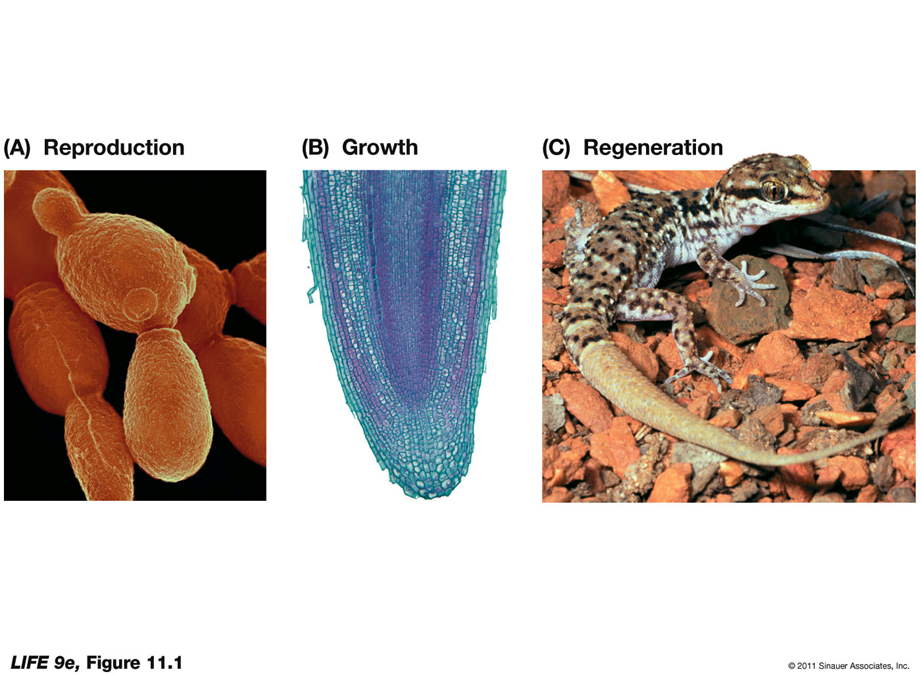

The life cycle of a organism is linked to cell division.

Unicellular organisms use cell division primarily for reproduction.

In multicellular organisms, cell division is also important in growth and repair of tissues (as well as reproduction)

Which four events must occur for cell division?

Reproductive signal: To initiate cell division

Replication: Of DNA

Segregation: Distribution of the DNA into the two new cells

Cytokinesis: Separation of the two new cells

HOW DO PROKARYOTIC CELLS DIVIDE?

Binary Fission in Prokaryotes

Prokaryotic cell division, primarily through binary fission, results in the formation of two genetically identical daughter cells. Here's how it works:

Reproductive Signals:

External Factors: The initiation of cell division in prokaryotes is influenced by external factors such as nutrient concentration and environmental conditions.

Nutrient Abundance: For many bacteria, an abundant supply of food speeds up the division cycle.

Chromosome Structure:

Single Chromosome: Most prokaryotes have a single, usually circular, DNA molecule.

Key Regions in Replication:

Ori (Origin of Replication): The site where DNA replication starts.

Ter (Termination Site): The site where DNA replication ends.

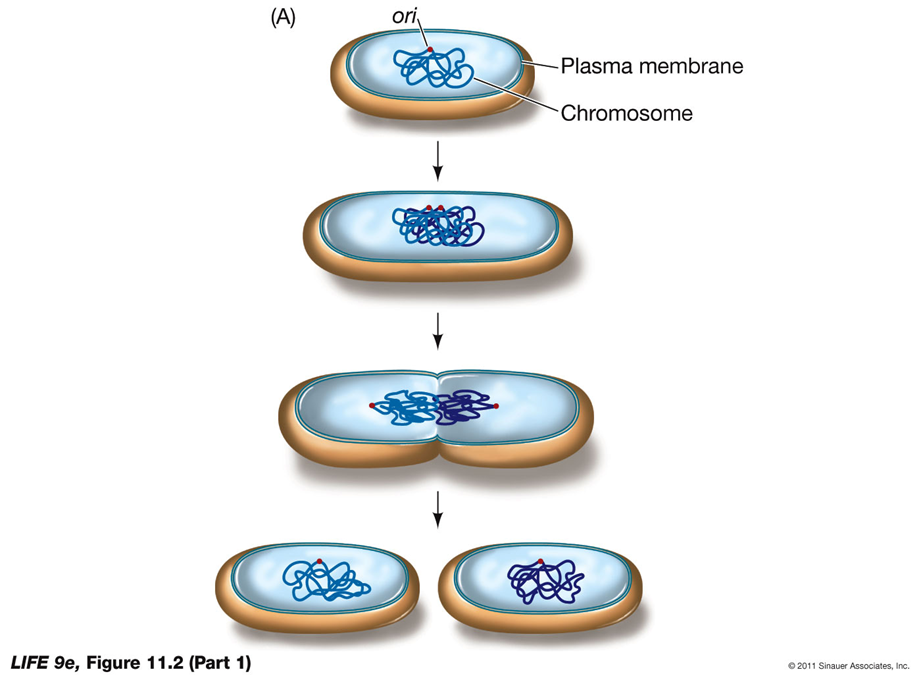

Process of Binary Fission:

Replication: The DNA molecule replicates from the origin (ori) to the termination site (ter).

Cell Growth: The cell grows, and the replicated DNA molecules move to opposite ends of the cell.

Cytokinesis: The cell membrane pinches inward, and a new cell wall forms, resulting in the separation of the two identical daughter cells.

Detailed Process of Cytokinesis:

In Prokaryotic Cells:

Membrane Pinching: After DNA replication, cytokinesis begins by pinching in of the plasma membrane.

Formation of a Ring: Protein fibers form a ring at the future division site.

Cell Wall Synthesis: As the membrane continues to pinch in, new cell wall materials are synthesized, resulting in the separation of the two cells.

HOW DO EUKARYOTIC CELLS DIVIDE?

In eukaryotes, signals for cell division are related to the needs of the entire organism.

Eukaryotes usually have many chromosomes; the processes of replication and segregation are more intricate.

HOW IS EUKARYOTIC CELL DIVISION CONTROLLED?

Eukaryotic cell division is regulated through various mechanisms to ensure proper growth, repair, and maintenance of tissues. Here are the key points:

Division Frequency: Some cells no longer divide or divide infrequently and need specific signals to initiate division.

Growth Factors: These are external chemical signals that stimulate cells to divide. Different types of growth factors play distinct roles in cell division.

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF): Released from platelets that initiate blood clotting, PDGF stimulates skin cells to divide and heal wounds.

Interleukins: Produced by some white blood cells, interleukins promote cell division in other white blood cells.

Erythropoietin: Produced in the kidneys, erythropoietin stimulates the division of bone marrow cells, leading to the production of red blood cells.

These mechanisms ensure that cells divide at the appropriate times, contributing to the overall health and function of the organism.

EUKARYOTIC CELL DIVISION:

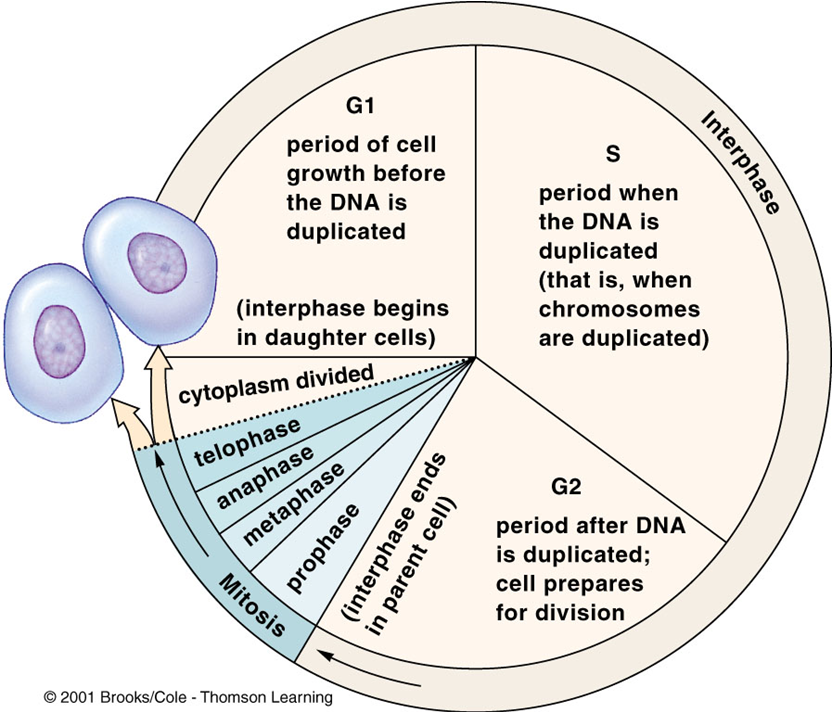

Interphase

Interphase is composed of three subphases:

G1 (Gap 1):

period of cell growth before the DNA is duplicated

Occurs between the end of cytokinesis and the onset of the S phase.

Chromosomes are single, unreplicated structures. (begin in daughter cells)

Many animal cells may enter a phase called G0, where they no longer divide or divide infrequently.

Restriction Point:

At the G1-to-S transition, a commitment is made to DNA replication and cell division.

S Phase (Synthesis Phase):

DNA replicates, resulting in each chromosome consisting of two sister chromatids.

During this time, nucleosomes begin to form around the newly synthesized DNA. The DNA wraps around histone proteins, organizing it into a more compact structure, but they don't fully condense into chromosomes just yet.

MORE INFO:

Histones: Proteins with positive charges that attract the negative phosphate groups of DNA, aiding in DNA packing.

Chromatin: Exists in an uncondensed form during interphase, but histones help DNA wrap around them to form nucleosomes down the line

Nucleosomes: Beadlike units formed by the interaction of DNA with histones.

Nucleosomes do not fully form until DNA begins condensing for cell division. (PROPHASE)

G2 (Gap 2):

Occurs at the end of the S phase.

The cell prepares for mitosis by undergoing checks to ensure the accuracy of DNA synthesis, preventing errors from being passed to new cells.

M Phase - PMATC

Mitosis and Cytokinesis:

Occur during this phase, leading to the division of the cell's nucleus and cytoplasm, respectively.

Control Mechanisms

Specific Signals:

Trigger the transition from one phase to another in the cell cycle.

Evidence from Experiments:

Cell fusion experiments provided evidence for the presence of substances that trigger these transitions.

When nuclei from cells at different stages were fused by polyethylene glycol, both nuclei entered the DNA replication phase (S phase).

WHAT HAPPENS DURING MITOSIS?

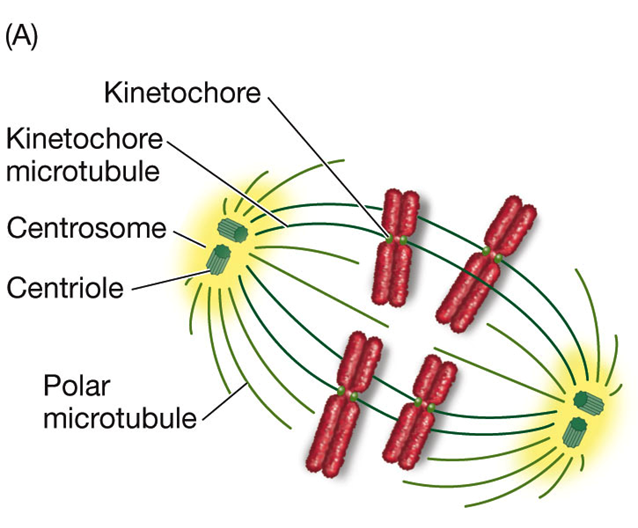

Segregation Aided by Other Structures:

Centrosome: Determines the plane of cell division.

Doubles during S phase and determines spindle orientation.

In animal cells, each centrosome consists of two centrioles—hollow tubes formed by microtubules—at right angles.

Centrioles: Stimulate the production of microtubules.

Movement of Centrosomes:

Move to opposite ends of the nuclear envelope during the G2-to-M transition.

Orientation determines the plane of cell division and the spatial relationship of the two new cells.

Microtubules and Spindle Apparatus:

High concentration of tubulin dimers (protien) surrounds the centrosomes.

These proteins initiate the formation of microtubules, leading to the formation of the spindle structure (spindle apparatus).

Plant cells lack centrosomes but have distinct microtubule organizing centers.

DNA Replication and Segregation:

After DNA replicates, its segregation occurs during mitosis.

Chromatin: The DNA molecule complexed with proteins.

Sister Chromatids: Held together by cohesin, which is removed during mitosis except at the centromere. ANAPHASE

Subphases of Mitosis:

Prophase

Prometaphase (term not always used)

Metaphase

Anaphase

Telophase

Prophase:

the nucleosomes undergo further compaction to form chromosomes

Cohesin disappears except at the centromere; chromatids become visible.

Kinetochores: Develop in the centromere regions for movement.

Spindle Formation:

Centrosomes serve as mitotic centers or poles; microtubules form between the poles to make the spindle.

The spindle has two types of microtubules:

Polar Microtubules: Extend from one centrosome to the other, overlapping in the center of the spindle. They provide structural support and a point to pull against during separation.

Kinetochore Microtubules: Attach specifically to the kinetochores on each chromatid. These microtubules are responsible for pulling the chromatids apart towards opposite poles of the cell.

THEY FULLY ATTACH IN METAPHASE NOT PROPHASE!

WHAT HAPPENS DURING MITOSIS PT 2?

Subphases of Mitosis:

Prophase

Metaphase:

Nuclear envelope breaks down.

nucleosomes become chromosomes

Chromosomes consisting of two chromatids attach to the kinetochore microtubules.

Chromosomes line up at the midline of the cell, known as the metaphase plate (an imaginary line in the middle of the cell).

Anaphase:

Microtubules Shortening: The microtubules themselves shorten, drawing the chromatids towards the poles, facilitating their separation.

Cohesin is hydrolyzed by separase (gets rid of the cohesin everywhere besides the centromere)

Sister chromatids, now referred to as daughter chromosomes, move to opposite ends of the spindle. This separation is controlled by M phase cyclin-Cdk —> (explained in detail later)

Cytoplasmic Dynein: MOTOR PROTIEN

Role: A protein called cytoplasmic dynein at the kinetochores uses ATP to generate energy, helping pull the chromatids along the microtubules toward the poles of the spindle.

Key Difference:

Cdks: Use ATP for phosphorylation to regulate proteins and drive cell cycle transitions.

Cytoplasmic Dynein: Uses ATP to produce mechanical energy for movement along microtubules.

Telophase:

Spindle breaks down.

Chromosomes uncoil.

Nuclear envelope and nucleoli reappear.

Two daughter nuclei are formed with identical genetic information.

Cytokinesis:

Animal Cells:

Plasma membrane pinches between the nuclei due to a contractile ring of microfilaments of actin and myosin aka the Cleavage Furrow

Plant Cells:

Vesicles from the Golgi apparatus appear along the plane of cell division.

These vesicles fuse to form a new plasma membrane.

Contents of vesicles form the cell plate—the beginning of the new cell wall.

Chromosome Movement:

Cytoplasmic Dynein: A protein at the kinetochores that hydrolyzes ATP to move chromosomes along the microtubules toward the poles.

Microtubules: Shorten to draw chromosomes toward the poles.

CYTOKENISIS:

In Eukaryotic Cells:

Animal Cells:

Cleavage Furrow: The cell membrane pinches inward, creating a cleavage furrow.

Actin and Myosin: Protein filaments (actin and myosin) form a contractile ring that tightens to separate the cell into two daughter cells.

Plant Cells:

Cell Plate Formation: Vesicles from the Golgi apparatus coalesce at the center of the cell to form a cell plate.

New Cell Wall: The cell plate grows outward until it fuses with the existing cell wall, dividing the cell into two separate daughter cells.

REGULATION OF THE CELL CYCLE:

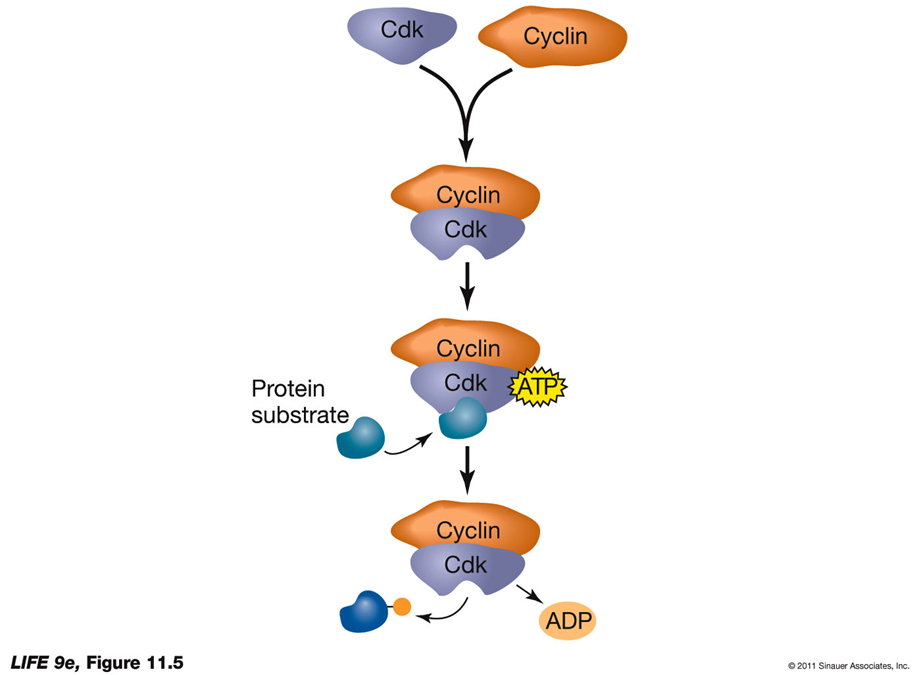

Transitions Depend on Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (Cdks):

Protein kinases are enzymes that transfer a phosphate group from ATP to a specific protein.

This process is called phosphorylation.

KINdly give a protien —> cdk’s are enzymes and NOT proteins

Why Phosphorylation Matters:

Phosphorylation changes the shape and function of the protein by altering its electrical charge.

This can activate or deactivate the protein, affecting its role in the cell.

What Are Cdks?

Cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) are a specific type of protein kinase.

Cdks are essential regulators of the cell cycle.

They are inactive on their own and need to bind to another protein called cyclin to become active.

How Do Cdks Control Cell Cycle Transitions?

Cdks regulate key steps of the cell cycle by phosphorylating target proteins.

This ensures the cell progresses from one phase to the next (e.g., G1 → S → G2 → M).

CYCLIN BINDING ACTIVATES CDK:

Cdk Activation:

Cdk undergoes a conformational change upon cyclin binding.

Knockout Mice:

In knockout mice, a specific protein is knocked out, leading to a mutation or the removal of a mutation.

Regulation of Cell Division:

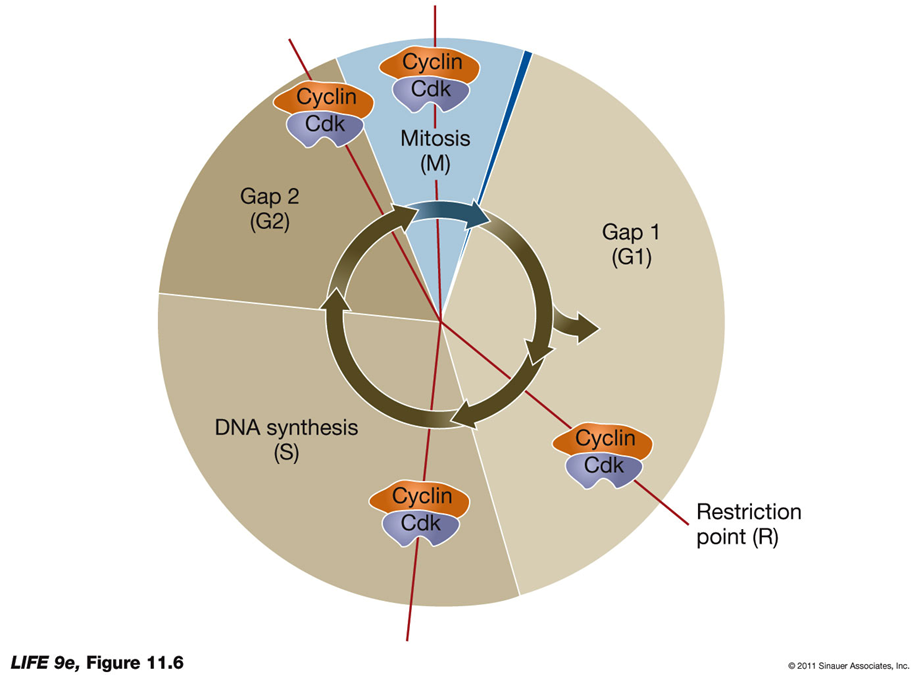

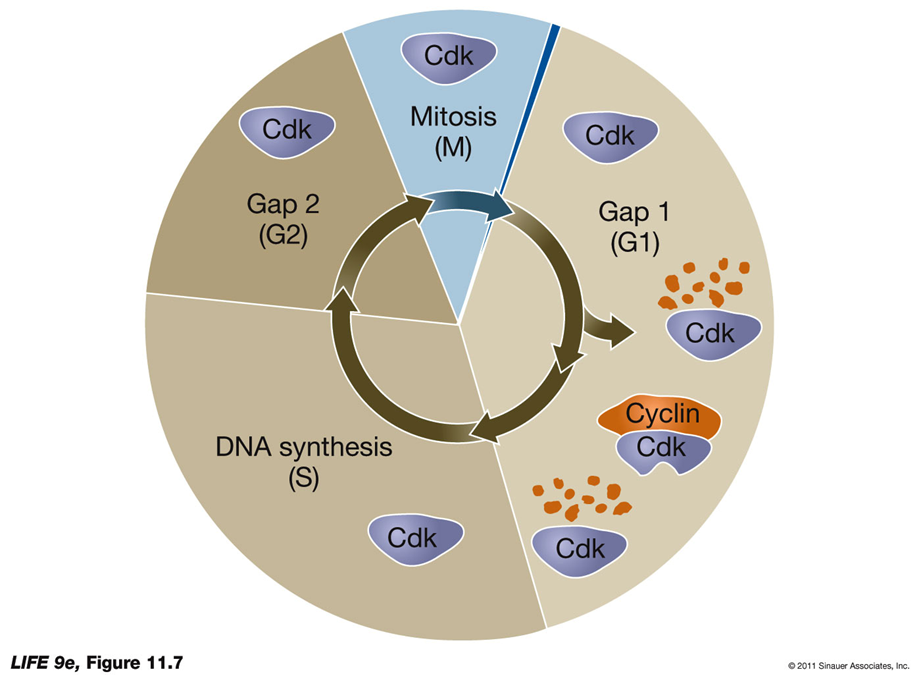

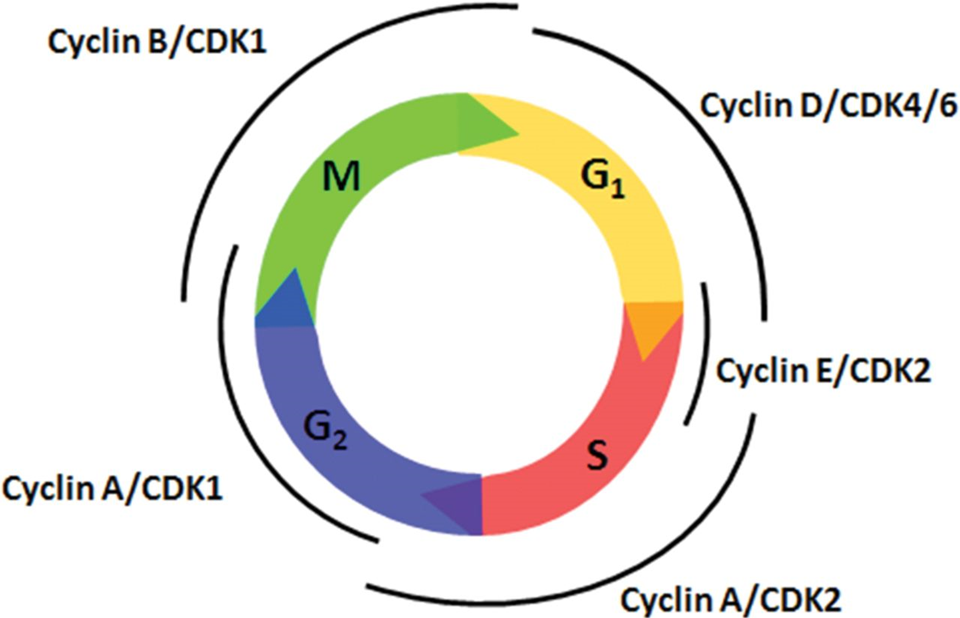

Different cyclin-Cdk complexes regulate various stages of the cell cycle, making the regulation of Cdks key to controlling cell division.

Cdks can be regulated by the presence or absence of cyclins (absence = they’re inactive)

Cyclins are degraded sequentially by proteases, ensuring timely progression through the cell cycle.

memory trick: cyclin is a PROtein and will be degraded by PROteases

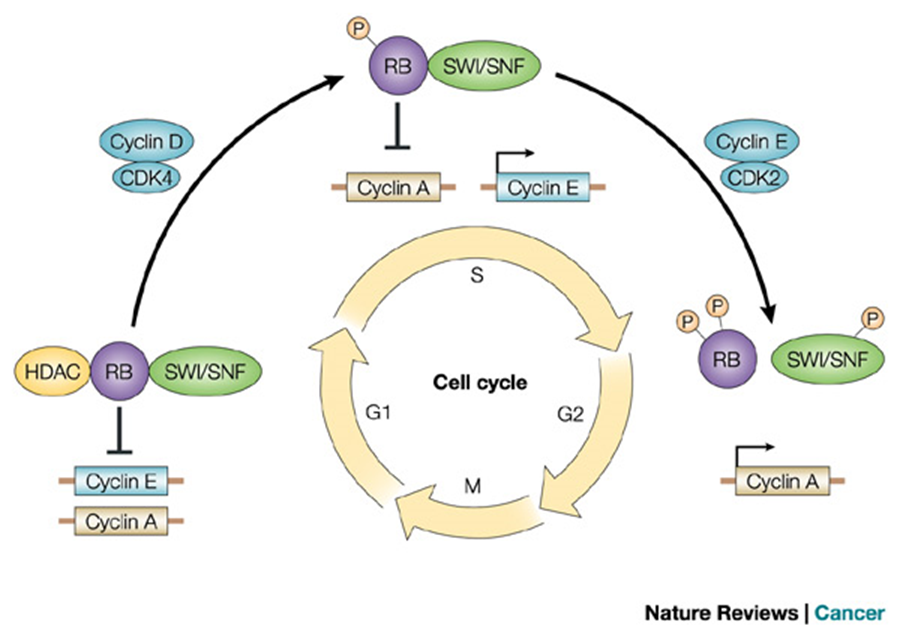

CYCLIN-DEPENDENT KINASES REGULATE PROGRESS THROUGH THE CELL CYCLE:

pic shows where CDKS are used and proteases degrade them after bc they are all TRANSITIONAL points

CELLS ARE TRANSIENT IN THE CELL CYCLE:

cyclins pull up when needed, proteases degrade them after to prevent a continuous cell cycle and other errors —> major cancer risk

CELLS ARE TRANSIENT IN THE CELL CYCLE:

Cyclin-Cdk Complexes and Checkpoints

Cyclin-Cdks: Act at cell cycle checkpoints to regulate progress.

Example:

If DNA is damaged during G1, the p21 protein is produced.

p21 binds to G1 Cdks, preventing their activation. (Pause! to (2) g1!)

This stops the cell cycle, allowing time for DNA repair.

G1-S Cyclin-Cdk Regulation

Progress Past the Restriction Point in G1:

Dependent on retinoblastoma protein (RB).

RB normally inhibits the cell cycle.

When phosphorylated by G1-S cyclin-Cdk, RB becomes inactive.

Inactive RB no longer blocks the cell cycle, allowing progression.

REstriction - REtinoblastoma

Tumor Suppressor Proteins:

Proteins like RB that regulate the cell cycle and prevent uncontrolled division.

(cyclin) D E A A B - 4 2 2 1 1 (cdK)

^ starting from g1\

CYCLINS ARE TRANSIENT IN THE CELL CYCLE:

VOCAB

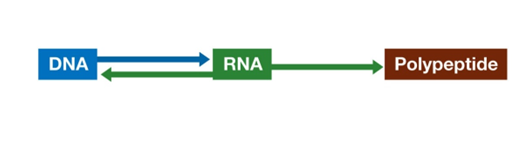

DOGMA OF MOLECULAR BIO:

The central dogma of molecular biology.” --> Biological information flows from DNA to RNA to protein

Exceptions to the central dogma:

Viruses: Non-cellular particles that reproduce inside cells; many have RNA instead of DNA.

Viruses can replicate by transcribing from RNA to RNA, and then making multiple copies by transcription.

Some viruses, such as HIV, are retroviruses.

After infecting a host cell a copy of the viral genome is incorporated into the host’s genome to make more RNA.

Synthesis of DNA from RNA is reverse transcription.

^^ DEFFF ON EXAM

Phenotype

The physical make-up and attributes of an organism.

Genotype

The genetic material (or blueprint) that determines phenotype. (genotype → phenotype)

Gene

The genetic material for one specific function (one gene = one protein).

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid, the genetic material of biological organisms.

Chromosomes

Enormous strings of DNA that possess thousands of individual genes.

VOCAB:

Mitosis

Produces daughter (progeny) cells identical in phenotype to parental cells. Genetic material is the same as the parental cell. Most tissue replication occurs through the process of mitosis.

Meiosis

Produces daughter (progeny) cells with a different phenotype than the parental cell. Genetic material is one half that of the parental cell. Meiotic replication usually results in the formation of gametes or cells involved in sexual reproduction. Allows for genetic variability and is responsible for complex patterns of inheritance.

CYCLINS ARE TRANSIENT IN THE CELL CYCLE:

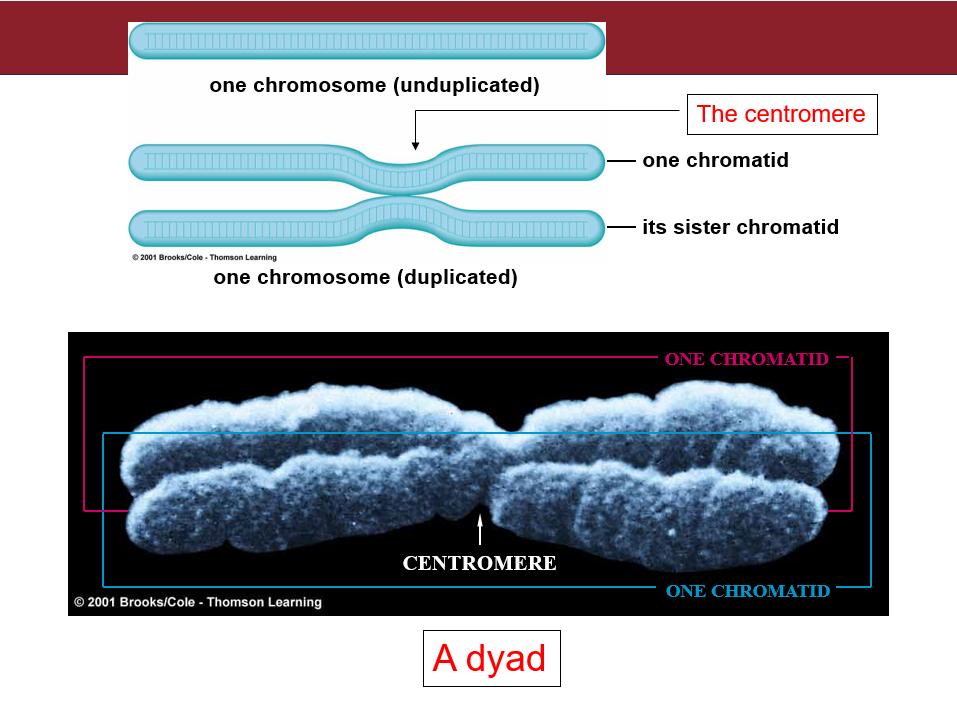

CHROMOSOMES AND CELL DIVISION:

Karyotype

Karyotype: The number, shapes, and sizes of the metaphase chromosomes in a eukaryotic cell.

Individual chromosomes can be recognized by:

Length

Position of centromere

Banding patterns

Cytogenetics: Uses karyotypes to aid in the diagnosis of certain diseases.

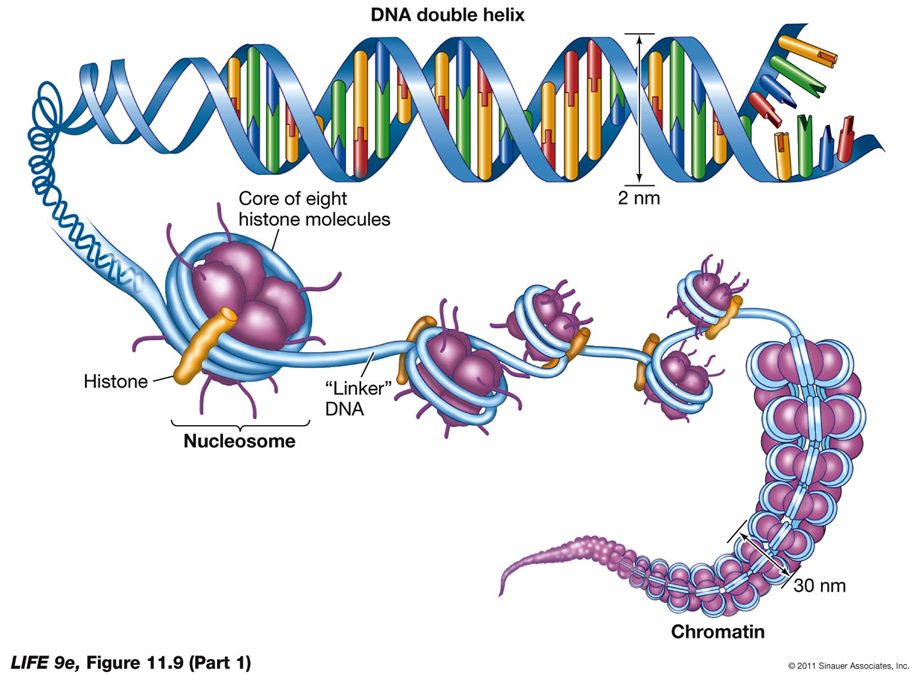

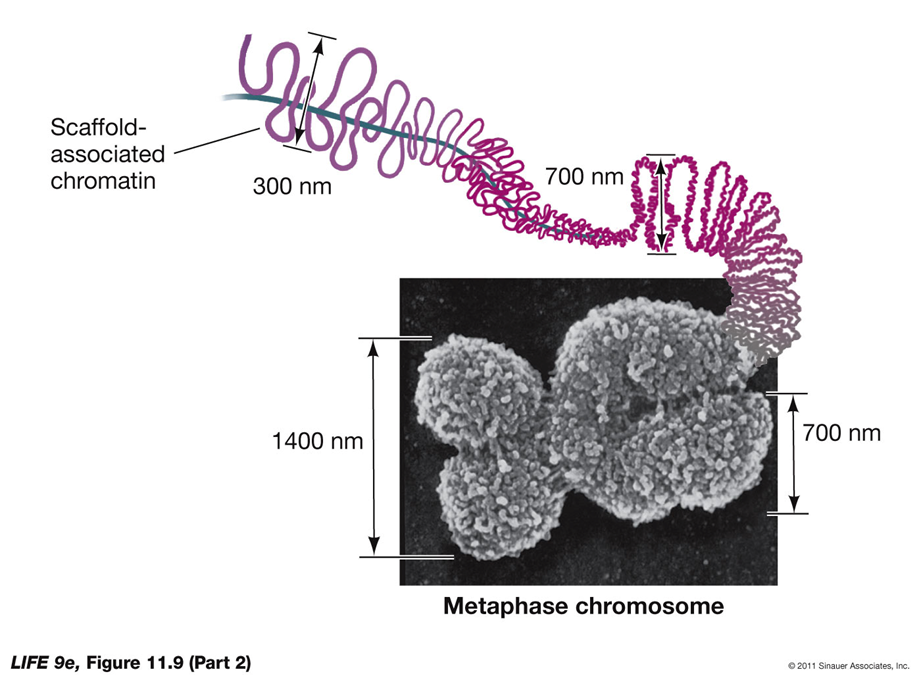

DNA Packing and Nucleosomes

Eukaryotic DNA: Extensively "packed" even during interphase.

Histones: Proteins with positive charges that attract the negative phosphate groups of DNA, aiding in DNA packing.

Chromatin: Exists in an uncondensed form during interphase, but histones help DNA wrap around them to form nucleosomes.

Nucleosomes: Beadlike units formed by the interaction of DNA with histones.

Nucleosomes do not fully form until DNA begins condensing for cell division.

DNA is Packed into a Mitotic Chromosome

DNA is Packed into a Mitotic Chromosome

WHAT ROLE DOES CELL DIVISION PLAY IN A SEXUAL LIFE CYCLE?

Asexual Reproduction:

Mitotic Division: Asexual reproduction relies on the mitotic division of the nucleus.

Unicellular Organisms: May reproduce themselves through mitosis.

Multicellular Organisms: Cells may break off to form a new individual.

Offspring: The result is genetically identical offspring, or clones, to the parent.

Sexual Reproduction:

Meiosis: Sexual reproduction involves meiosis, a different type of cell division, which reduces the chromosome number by half to form gametes (sperm and eggs).

Genetic Diversity: Meiosis introduces genetic variation through the processes of crossing over and independent assortment.

Fertilization: Fusion of gametes during fertilization restores the diploid chromosome number and creates a genetically unique organism. 23 per parent = 46 total

Summary:

Asexual Reproduction:

Based on mitotic division.

Results in clones identical to the parent.

Sexual Reproduction:

Involves meiosis.

Ensures genetic diversity and the creation of genetically unique offspring.

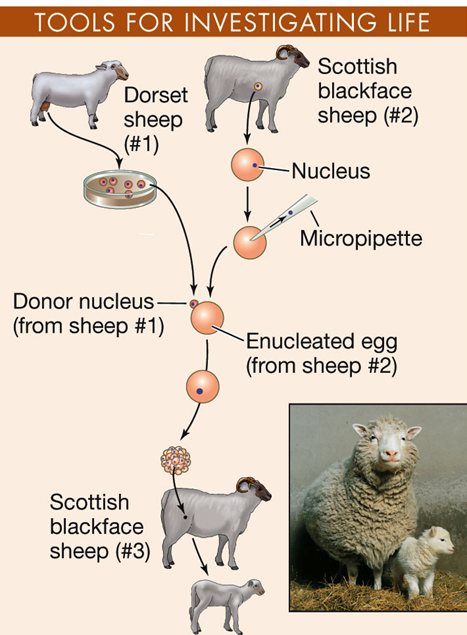

DOLLY THE SHEEP:

Dolly the sheep cloned from a single mammary cell in 1996

Changed all the rules but is a bioethical nightmare.

WHAT ROLE DOES CELL DIVISON PLAY IN A SEXUAL LIFE CYCLE?

Sexual reproduction: The offspring are not identical to the parents.

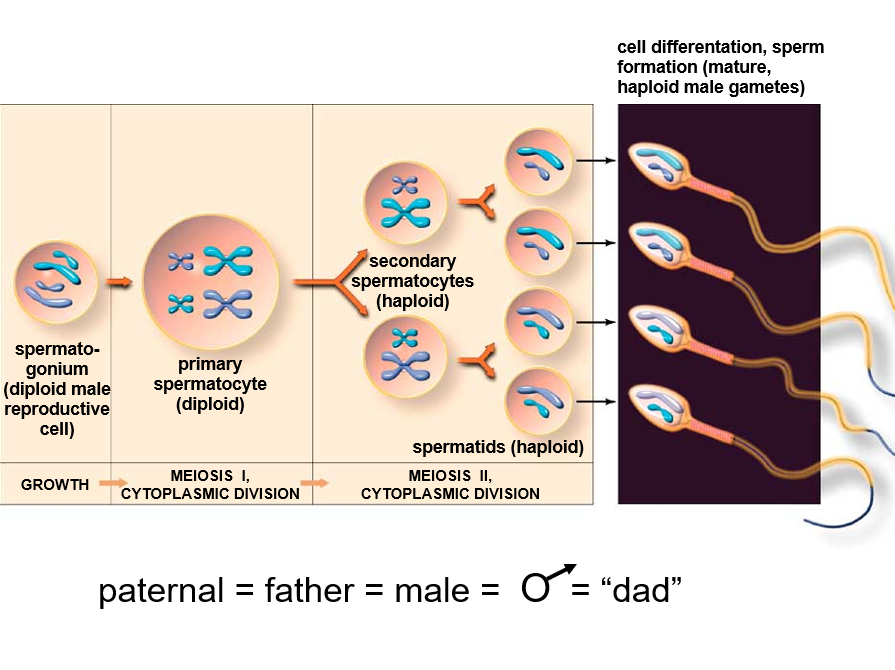

It requires gametes (specialized reproductive cells) created by meiosis; two parents each contribute one gamete to an offspring.

Gametes—and offspring—differ genetically from each other and from the parents.

Somatic cells—body cells not specialized for reproduction.

Germ cells—body cells specialized for reproduction and meiosis (diploid). Produce gametes

Diploid cells contain homologous pairs of chromosomes with corresponding genes. Each gamete contributes one homolog.

Gametes contain only one set of chromosomes.

Haploid: Number of chromosomes = n

Fertilization: Two haploid gametes (female egg and male sperm) fuse to form a diploid zygote; chromosome number = 2n

SO BASICALLY diploids are the set of chromosomes you always have and then the germ ones are the ones specifically making haploid gametes to be used for reproduction and meiosis. all germ cells are diploid, but not all diploid cells are germ cells

Germ cells undergo meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half.

Result: Produces haploid gametes (sperm and egg cells), each with one set of chromosomes (23 in humans).

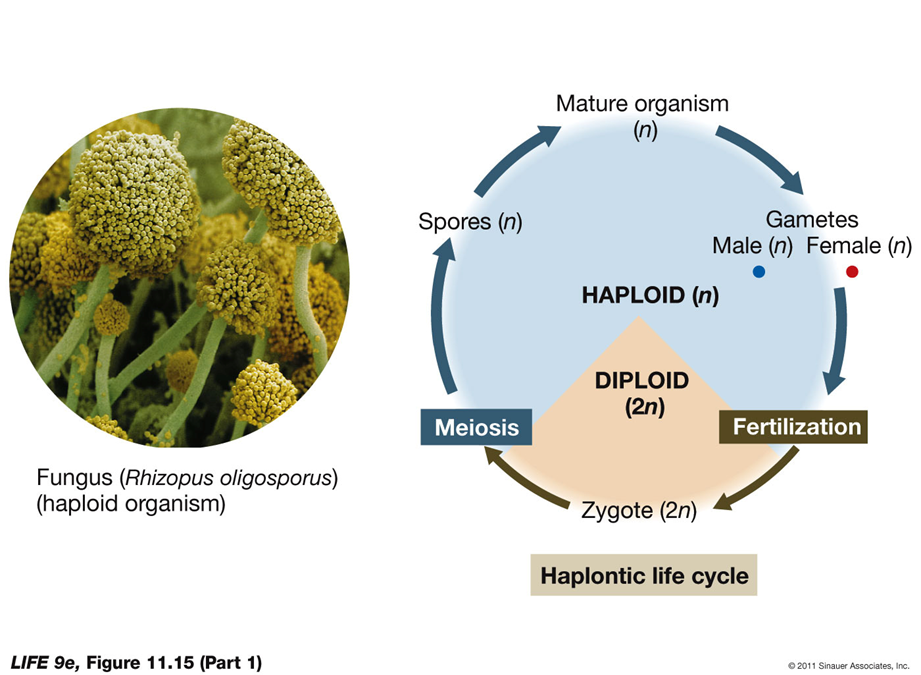

Several kinds of sexual life cycles

Haplontic life cycle: In protists, fungi, and some algae—zygote is only diploid stage

After zygote forms it undergoes meiosis to form haploid spores, which germinate to form a new organism

Organism is haploid, produces gametes by mitosis—cells fuse to form zygote

Role of Cell Division in Sexual Life Cycles

Alternation of Generations

Definition: Seen in most plants and some protists, alternation of generations involves two distinct life stages—haploid and diploid.

Process:

Meiosis: Gives rise to haploid spores.

Haploid Generation (Gametophyte): Spores divide by mitosis to form the gametophyte.

Gamete Formation: The gametophyte forms gametes by mitosis.

Fertilization: Gametes fuse to form a diploid zygote (sporophyte).

Diploid Generation (Sporophyte): The sporophyte grows by mitosis.

Diplontic Life Cycle

Definition: Observed in animals and some plants, the diplontic life cycle has gametes as the only haploid stage.

Process:

Diploid Mature Organism: The mature organism is diploid.

Meiosis: Produces haploid gametes.

Fertilization: Gametes fuse to form a diploid zygote.

Mitosis: The zygote divides by mitosis to form a mature diploid organism.

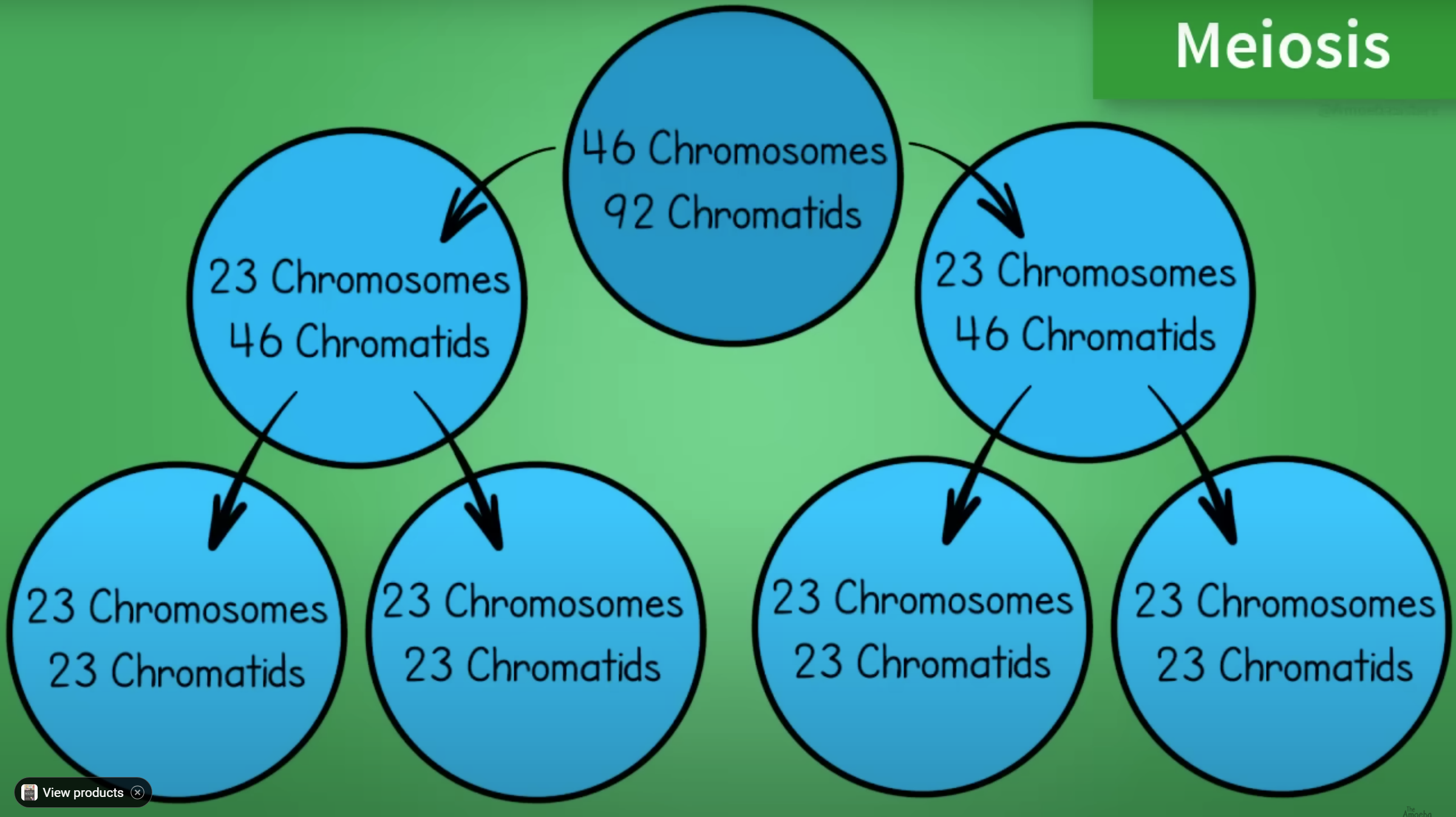

What Happens during Meiosis?

Meiosis is a specialized type of cell division that generates genetic diversity in sexually reproducing organisms. It involves two nuclear divisions, but the DNA is replicated only once. The primary functions of meiosis are to reduce the chromosome number from diploid to haploid, ensure that each haploid cell has a complete set of chromosomes, and generate diversity among the products.

Key Features of Meiosis:

Sexual Reproduction: Generates diversity among individual organisms by allowing the random selection of half the diploid chromosome set to form a haploid gamete, which then fuses with another to form a diploid cell.

No Genetic Replication: DNA replication occurs only once during meiosis, although there are two nuclear divisions.

Stages of Meiosis:

Meiosis I:

S Phase: Preceded by an S phase during which DNA is replicated, resulting in chromosomes consisting of two sister chromatids held together by cohesin proteins.

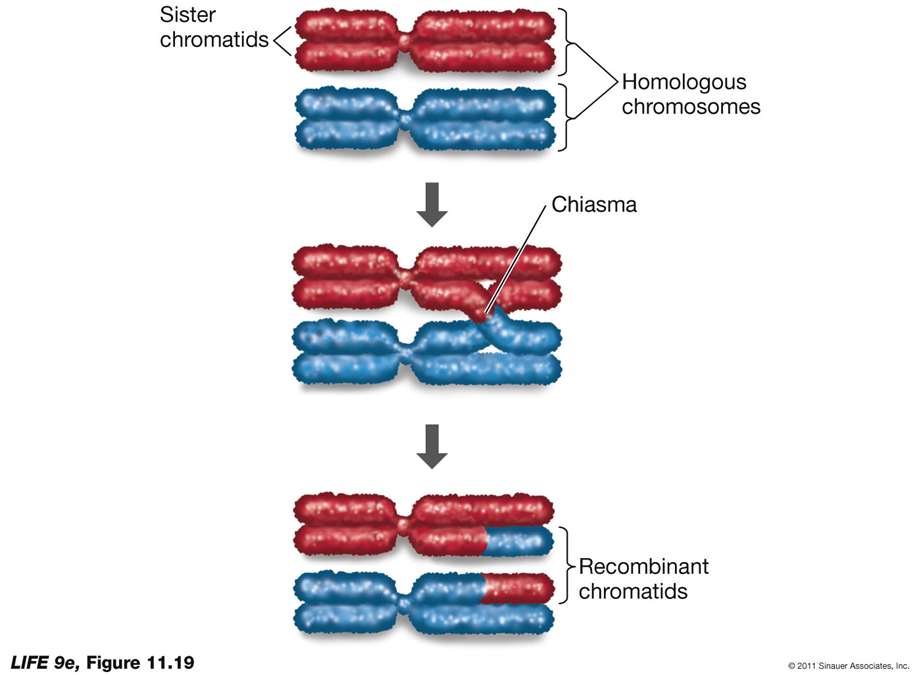

Prophase I: Homologous chromosomes pair up (synapsis) to form a tetrad or bivalent. Chromatin continues to coil and compact, and homologs are held together by chiasmata where crossing over occurs, leading to genetic recombination.

Metaphase I: Chromosomes line up at the equatorial plate, with homologous pairs held together by chiasmata.

Anaphase I: Homologous chromosomes separate, resulting in daughter nuclei containing only one set of chromosomes, each consisting of two chromatids.

Telophase I: Occurs in some organisms with the nuclear envelope reaggregating, followed by an interphase called interkinesis. In other organisms, meiosis II begins immediately.

Unique Features of Meiosis I:

Synapsis: Homologous pairs of chromosomes come together and pair along their entire lengths.

Separation: After metaphase I, homologous pairs separate, but sister chromatids remain together.

Crossing Over: Exchange of genetic material at the chiasmata results in recombinant chromatids, increasing genetic variability.

Prophase I Duration:

Human Males: Prophase I lasts about 1 week, and the entire meiotic cycle takes about 1 month.

Human Females: Prophase I begins before birth and can last decades, ending during the monthly ovarian cycle.

Meiosis II:

Continuation: In organisms where Telophase I does not result in complete interphase, meiosis II proceeds immediately.

Similar to Mitosis: Sister chromatids separate in a manner similar to mitotic division, resulting in four haploid daughter cells.

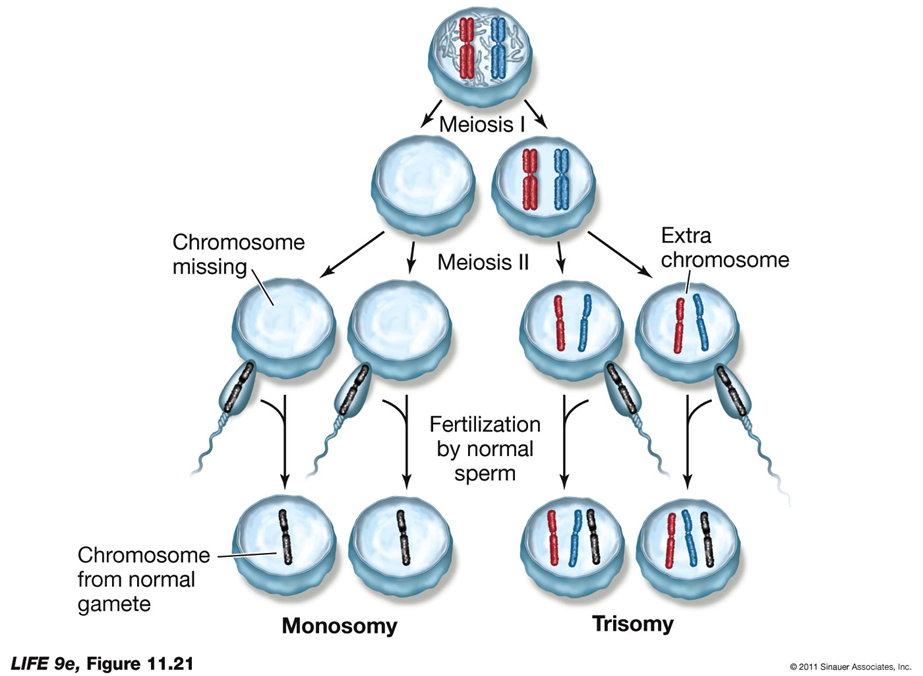

Meiotic Errors

Nondisjunction:

Definition: Occurs when homologous pairs fail to separate at anaphase I, sister chromatids fail to separate, or homologous chromosomes may not remain together.

Result: Leads to aneuploidy, where chromosomes are either lacking or present in excess.

Cause: May be due to a lack of cohesins that hold the homologous pairs together.

Outcome: Without cohesins, both homologs may go to the same pole, resulting in gametes with two of the same chromosome or none.

Aneuploidy in Humans:

Trisomy 21:

If both chromosome 21 homologs go to the same pole and the resulting egg is fertilized, the zygote will be trisomic for chromosome 21, leading to Down syndrome.

Monosomy: A fertilized egg that did not receive a copy of chromosome 21 will be monosomic, which is lethal.

Translocation:

A piece of chromosome may break away and attach to another chromosome.

Individuals with a translocated piece of chromosome 21 plus two normal copies will have Familial Down syndrome.

Common Occurrences:

Trisomies and Monosomies:

Common in human zygotes, but most embryos with these conditions do not survive.

Trisomies and monosomies for chromosomes other than 21 are typically lethal and cause many miscarriages.

Polyploidy:

Definition: Organisms with complete extra sets of chromosomes.

Types:

Triploid (3n), tetraploid (4n), and even higher ploidy levels.

Mitosis and Meiosis:

Mitosis can occur because each chromosome behaves independently.

Polyploidy can prevent meiosis as not all chromosomes will have a homolog, preventing anaphase I.

Applications:

Polyploidy can enhance crop plants.

Triploidy is used to produce sterile trout for stocking rivers.

IN A LIVING ORGANISM, HOW DO CELLS DIE?

Types of Cell Death:

Necrosis:

Occurs when a cell is damaged or starved for oxygen or nutrients.

The cell swells and bursts, releasing its contents to the extracellular environment, which can cause inflammation.

Apoptosis:

Genetically programmed cell death. Occurs for several reasons:

Cell is no longer needed: For example, the connective tissue between the fingers of a fetus.

Old cells prone to genetic damage: Such as blood cells and epithelial cells that die after days or weeks.

Infection: Viral and bacterial infections can induce apoptosis.

Events of Apoptosis:

Cell detaches from its neighbors.

Cuts up its chromatin into nucleosome-sized pieces.

Forms membranous lobes called “blebs” that break into fragments.

Surrounding living cells ingest the remains of the dead cell.

Control of Cell Death Cycle:

Signals:

Lack of a mitotic signal (growth factor).

Recognition of damaged DNA.

External signals cause membrane proteins to change shape and activate enzymes called caspases, which hydrolyze proteins of membranes.

HOW DOES UNREGULATED CELL DIVISION LEAD TO CANCER?

Differences in Cancer Cells:

Loss of Control:

Cancer cells lose control over cell division and apoptosis.

They can migrate to other parts of the body.

Response to Signals:

Normal cells divide in response to extracellular signals like growth factors.

Cancer cells don’t respond to these signals and grow almost continuously.

Tumors:

Benign Tumors:

Resemble the tissue they grow from.

Grow slowly and remain localized.

Not cancerous but can obstruct an organ or function.

Malignant Tumors:

Do not resemble the tissue they grow from and may have irregular structures.

Can invade surrounding tissue and travel through the bloodstream or lymph system (metastasis).

Regulation of Cell Division:

Positive Regulators:

Normal regulators stimulate the cell cycle, like growth factors.

Oncogene proteins are positive regulators in cancer cells, often derived from normal regulators that are overactive or in excess.

Negative Regulators:

Normal regulators inhibit the cell cycle, like RB (retinoblastoma protein).

Tumor suppressors, such as p21, p53, and RB, are normally active but may be blocked in cancer cells.

Cancer Treatments:

Cell Cycle Inhibition:

Taxol interferes with the mitotic spindle.

Herceptin targets the HER2 growth factor receptor in some breast cancers.

Most treatments rely on the rapid division of cancer cells and cause DNA damage.

Nucleoside analogs like 5-fluorouracil block thymine, a base of DNA.

Radiation therapy can also damage DNA and kill tumor cells.

HOW IS THE INFORMATION CONTENT IN DNA TRANSCRIBED TO PRODUCE DNA?

Initiation

Elongation

Termination

Transcription Components and RNA vs. DNA Transcription Components:

DNA Template:

One of the two strands of DNA serves as the template for base pairing.

Nucleoside Triphosphates:

ATP (adenosine triphosphate)

GTP (guanosine triphosphate)

CTP (cytidine triphosphate)

UTP (uridine triphosphate) are used as substrates.

RNA Polymerase:

The enzyme responsible for synthesizing RNA from the DNA template.

Differences between RNA and DNA:

Strands:

RNA: Usually consists of one polynucleotide strand.

DNA: Typically consists of two polynucleotide strands.

Sugar:

RNA: Contains ribose.

DNA: Contains deoxyribose.

Bases:

RNA: Contains uracil (U) instead of thymine (T).

DNA: Contains thymine (T).

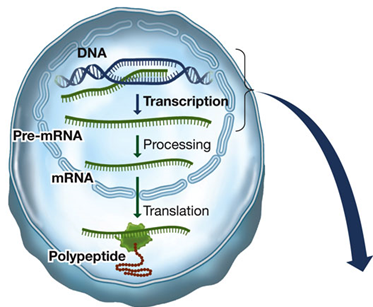

How Does Information Flow from Genes to Proteins?

Overview:

The flow of genetic information from DNA to proteins involves several key steps, each facilitated by different molecules and processes. This journey is known as the central dogma of molecular biology and includes transcription and translation.

Transcription—copies information from a DNA sequence (a gene) to a complementary RNA sequence

Translation—converts RNA sequence to amino acid sequence of a polypeptide

Transcription:

DNA Template:

One of the two strands of DNA serves as a template for RNA synthesis.

Bases in RNA can pair with the DNA template strand, with adenine pairing with uracil (instead of thymine).

Nucleoside Triphosphates:

The substrates for RNA synthesis are ATP, GTP, CTP, and UTP.

RNA Polymerase:

Catalyzes the synthesis of RNA.

RNA polymerases are processive, meaning a single enzyme-template binding results in the polymerization of hundreds of RNA bases.

Unlike DNA polymerases, RNA polymerases do not require primers and lack a proofreading function.

Initiation:

Requires a promoter, a special DNA sequence where RNA polymerase binds.

The promoter indicates where to start transcription and which DNA strand to transcribe.

Part of each promoter is the initiation site where transcription begins.

TATA-Binding Protein (TBP) and other transcription factors help RNA polymerase find the promoter and bind correctly.

Types of RNA Polymerase in Eukaryotes:

RNA Polymerase I: Synthesizes rRNA (ribosomal RNA).

RNA Polymerase II: Synthesizes mRNA (messenger RNA).

RNA Polymerase III: Synthesizes rRNA and tRNA (transfer RNA).

R.M.R-T

RNA vs. DNA:

Strands:

RNA is usually single-stranded.

DNA is typically double-stranded.

Sugar:

RNA contains ribose.

DNA contains deoxyribose.

Bases:

RNA contains uracil (U) instead of thymine (T).

Translation:

After transcription, the mRNA is used as a template for protein synthesis during translation. This process involves:

mRNA: Carries the genetic code from DNA.

Ribosomes: Facilitate the decoding of mRNA into a polypeptide chain. Ribosomes Read

tRNA: Transports amino acids to the ribosome and matches them with the mRNA codon through its anticodon.

Transcription: Elongation

Elongation:

Process: RNA polymerase unwinds DNA about ten base pairs at a time.

Direction: Reads the template strand in the 3′ to 5′ direction.

RNA Transcript: Antiparallel to the DNA template strand, adding nucleotides to its 3′ end.

Proofreading: RNA polymerases do not proofread and correct mistakes.

Speed: Transcription occurs at a rate of approximately 40 bases per second.

Transcription: Termination

Termination:

Specified by DNA Sequence: Termination occurs at specific DNA base sequences.

RNA Polymerase I: Termination factor (protein) binds to pre-RNA.

RNA Polymerase II: Polymerization continues, but pre-mRNA is cleaved at the poly-A signal sequence.

RNA Polymerase III: Transcription is terminated at a “pause” site (a string of uracils).

MEMORY TRICK:

"I Terminate Fast":

RNA Polymerase I: Uses a termination factor (protein) to stop transcription.

"II Cuts Ahead":

RNA Polymerase II: Keeps going but stops when the pre-mRNA is cleaved at the poly-A signal sequence (like cutting the transcript to finish).

"III Pauses to Stop":

RNA Polymerase III: Stops at a pause site—a sequence of uracils (U) that acts as a signal to end transcription.

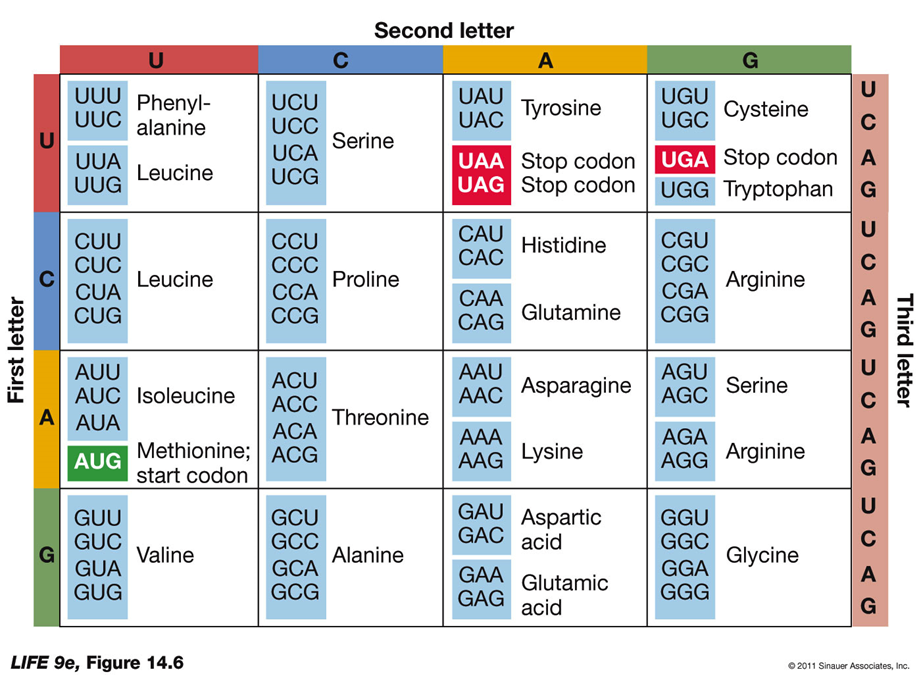

The Genetic Code

PROCESS TO GET HERE: Translation:

After transcription, the mRNA is used as a template for protein synthesis during translation. This process involves:

mRNA: Carries the genetic code from DNA.

Ribosomes: Facilitate the decoding of mRNA into a polypeptide chain. Ribosomes Read

tRNA: Transports amino acids to the ribosome and matches them with the mRNA codon through its anticodon.

Definition:

Genetic Code: Specifies which amino acids will be used to build a protein.

Codon: A sequence of three bases, each specifying a particular amino acid.

Start and Stop Codons:

Start Codon (AUG): The initiation signal for translation.

Stop Codons (UAA, UAG, UGA): Signals to stop translation and release the polypeptide.

Characteristics:

Redundancy: Most amino acids are specified by more than one codon, making the genetic code redundant (degenerate).

Specificity: The genetic code is not ambiguous; each codon specifies only one amino acid.

Universality: The genetic code is nearly universal across all living organisms, with minor variations. This commonality provides a shared language for evolution.

Evolution: The genetic code is ancient and has remained intact throughout evolutionary history.

Genetic Engineering: The common genetic code facilitates genetic engineering, allowing genes to be transferred between different organisms.

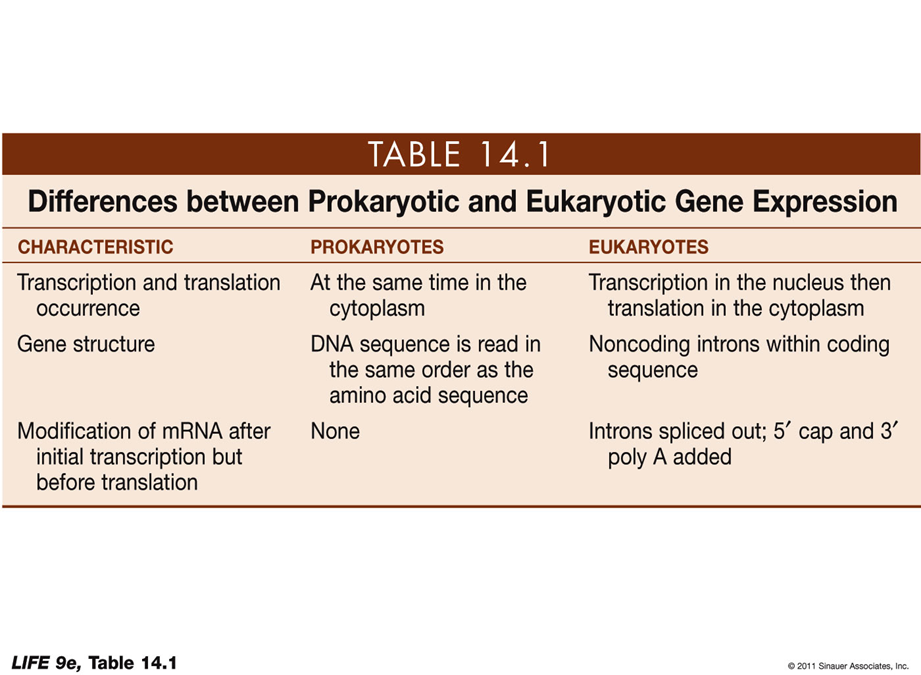

PROKARYOTIC VS EUKARYOTIC GENE EXPRESSION

CHARACTERISTIC: Transcription and translation occurrence

Prokaryotes: At the same time in the cytoplasm

Eukaryotes: Transcription in the nucleus then translation in the cytoplasm

CHARACTERISTIC: Gene structure

Prokaryotes: DNA sequence is read in the same order as the amino acid sequence

Eukaryotes: Noncoding introns within coding sequence

CHARACTERISTIC: Modification of mRNA after initial transcription but before translation

Prokaryotes: None

Eukaryotes: Introns spliced out; 5' cap and 3' poly A added

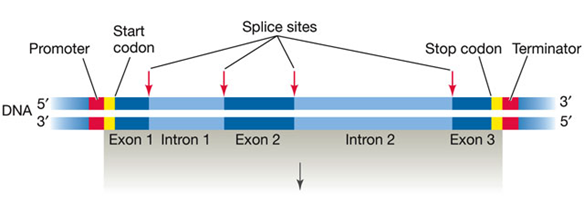

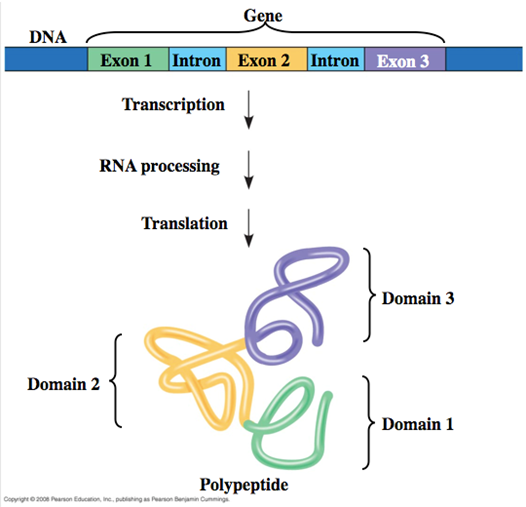

HOW IS EUKARYOTIC DNA TRANSCRIBED AND THE RNA PROCESSED?

Transcription:

DNA Template:

Eukaryotic genes contain both noncoding sequences (introns) and coding sequences (exons).

RNA Synthesis:

The process begins with the synthesis of a primary mRNA transcript (pre-mRNA) that includes both introns and exons.

RNA Processing:

Introns and Exons:

Introns: Noncoding sequences that are removed from the final mRNA.

Exons: Coding sequences that are retained in the final mRNA.

Splicing:

The primary mRNA transcript undergoes splicing to remove introns and join exons together.

The result is a mature mRNA that only contains exons.

HOW IS EUKARYOTIC DNA TRANSCRIBED AND THE RNA PROCESSED?

HOW IS EUKARYOTIC DNA TRANSCRIBED AND THE RNA PROCESSED?

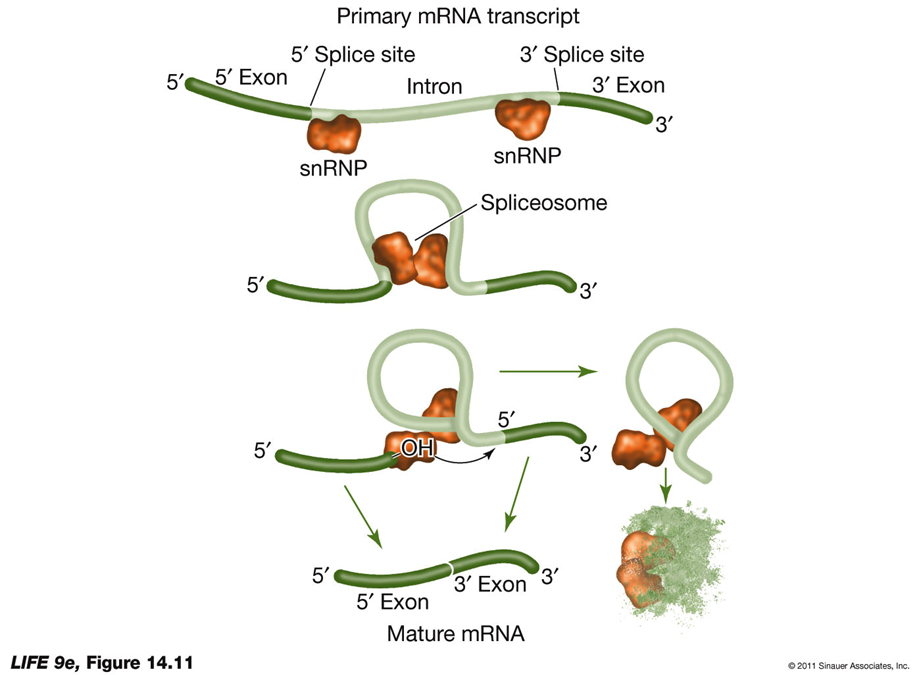

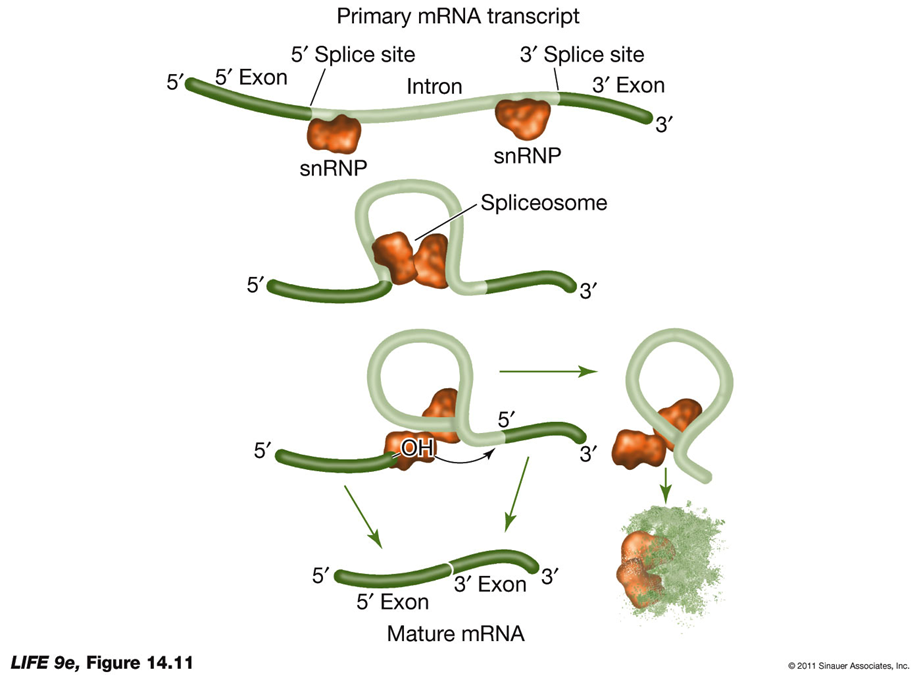

RNA Splicing and Alternative RNA SplicingRNA Splicing:

Process: RNA splicing removes introns and splices exons together to produce mature mRNA.

snRNPs: Newly transcribed pre-mRNA is bound at both ends by small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs).

Consensus Sequences: These are short sequences between exons and introns where snRNPs bind, including near the 3′ end of the intron.

Spliceosome Formation: With energy from ATP, proteins are added to form an RNA-protein complex known as the spliceosome.

Splicing Mechanism: The spliceosome cuts the pre-mRNA, releases introns, and splices exons together.

Function: Introns interrupt but do not scramble the DNA sequence that encodes a polypeptide. Sometimes, separated exons code for different domains (functional regions) of the protein.

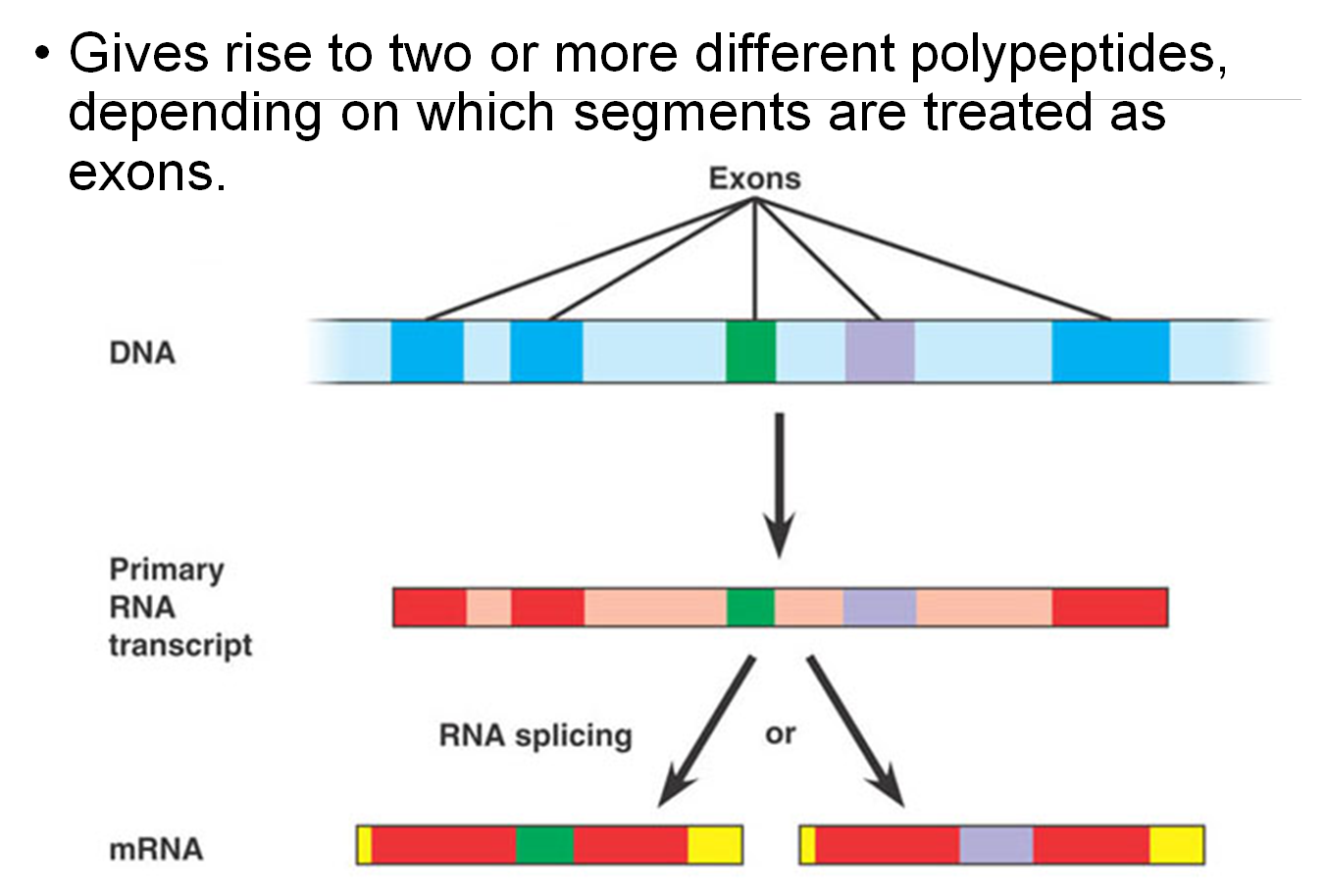

Alternative RNA Splicing:

Definition: Alternative RNA splicing allows for the production of multiple proteins from a single gene by including or excluding different sets of exons during RNA processing.

Exons and Protein Domains

Domains in Proteins:

Proteins are composed of discrete structural and functional regions known as domains.

Encoding by Exons:

These domains are often encoded by distinct exons within a gene.

Facilitating Evolution:

Exon Shuffling: The recombination between exons can facilitate evolution. This process allows for the creation of new proteins by mixing and matching different exons, leading to new functional properties in proteins.

example just to understand:

Antibodies:

Antibodies are proteins with domains that bind specific pathogens.

Through exon shuffling, new combinations of binding domains can evolve, helping organisms fight off new diseases.

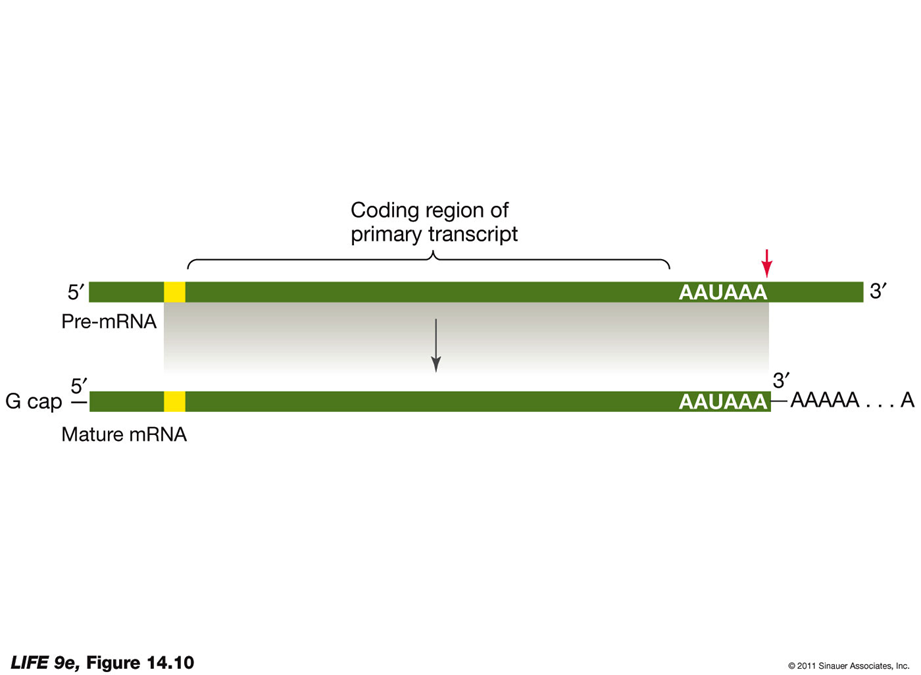

How Is Eukaryotic DNA Transcribed and the RNA Processed?

Modification of Pre-mRNA in the Nucleus5′ Cap Addition:

G Cap:

Added at the 5′ end of the pre-mRNA.

Composed of modified guanosine triphosphate.

Functions:

Facilitates the binding of mRNA to the ribosome.

Protects mRNA from being digested by ribonucleases.

3′ Poly-A Tail Addition:

Poly-A Tail:

Added at the 3′ end of the pre-mRNA.

Begins with an AAUAAA sequence after the last codon, signaling an enzyme to cut the pre-mRNA.

Another enzyme adds 100 to 300 adenine nucleotides, forming the poly-A tail.

Functions:

May assist in the export of mRNA from the nucleus.

Important for the stability of the mRNA.

Export of Mature mRNA from the Nucleus

Process Overview:

Mature mRNA molecules must leave the nucleus to be translated into proteins in the cytoplasm. This export process involves several key steps:

TAP Protein Binding:

A TAP protein binds to the 5′ end of the mature mRNA.

This TAP-mRNA complex binds to other proteins.

Recognition by Nuclear Pore Receptors:

The proteins bound to TAP-mRNA are recognized by receptors located at the nuclear pore complex.

Translocation through Nuclear Pores:

These receptor-protein interactions facilitate the translocation of the mRNA through the nuclear pore into the cytoplasm.

Unused pre-mRNAs remain in the nucleus and do not go through this export process.

HOW IS RNA TRANSLATED INTO PROTIENS?

Translation: From RNA to Proteins

Translation is the process by which the genetic code carried by mRNA is used to synthesize proteins. This process involves several key components and steps:

OVERVIEW: Translation:

After transcription, the mRNA is used as a template for protein synthesis during translation. This process involves:

mRNA: Carries the genetic code from DNA.

Ribosomes: Facilitate the decoding of mRNA into a polypeptide chain. Ribosomes Read

tRNA: Transports amino acids to the ribosome and matches them with the mRNA codon through its anticodon.

tRNA: The Adapter Molecule

Function: Links information in mRNA codons with specific amino acids.

Specificity: Each amino acid has a specific type or “species” of tRNA.

Key Events:

Reading mRNA Codons: tRNAs must read the mRNA codons correctly.

Delivering Amino Acids: tRNAs must deliver the amino acids corresponding to each codon.

Functions of tRNA:

Binding to Amino Acid: tRNA binds to an amino acid, becoming “charged”.

Associating with mRNA: tRNA associates with mRNA molecules through complementary base pairing.

Interacting with Ribosomes: tRNA interacts with ribosomes to add its amino acid to the growing polypeptide chain.

Structure: The three-dimensional shape of tRNA results from base pairing within the molecule.

3′ End: The amino acid attachment site that binds covalently to the amino acid.

Anticodon: Located at the midpoint of the tRNA sequence, this is the site of base pairing with mRNA and is unique for each species of tRNA.

Example:

DNA codon for arginine: 3′-GCC-5′

Complementary mRNA: 5′-CGG-3′

Anticodon on the tRNA: 3′-GCC-5′ (charged with arginine).

Wobble: The base at the 3′ end of the codon is not always observed with high specificity.

Example: Codons for alanine (GCA, GCC, and GCU) are recognized by the same tRNA.

Function: Wobble allows cells to produce fewer tRNA species while maintaining specificity of the genetic code.

Activating Enzymes: Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases

Function: Charge tRNA with the correct amino acids.

Specificity: Each enzyme is highly specific for one amino acid and its corresponding tRNA.

Process: Known as the second genetic code, involving three-part active sites that bind a specific amino acid, a specific tRNA, and ATP.

Ribosome: The Workbench for Protein Synthesis

Function: Holds mRNA and charged tRNAs in the correct positions for polypeptide chain assembly.

Structure:

Subunits: Ribosomes have two subunits—large and small.

Large Subunit: In eukaryotes, it has three rRNA molecules and 49 different proteins.

Small Subunit: Contains one rRNA and 33 proteins.

Binding Sites:

A (Amino Acid) Site: Binds with the anticodon of a charged tRNA.

P (Polypeptide) Site: Where tRNA adds its amino acid to the growing chain.

E (Exit) Site: Where tRNA sits before being released from the ribosome.

Fidelity Function: Ensures proper binding through temporary hydrogen bonds between the base pairs. Incorrect tRNAs are rejected if the match is not validated.

Steps of Translation:

Initiation: The small ribosomal subunit binds to the mRNA and initiates translation with the start codon (AUG).

Elongation: tRNAs bring amino acids to the ribosome, and the polypeptide chain is elongated.

Termination: Translation stops when a stop codon (UAA, UAG, UGA) is reached, and the polypeptide is released.

Small subunit rRNA validates the match—if hydrogen bonds have not formed between all three base pairs, the tRNA must be an incorrect match for that codon and the tRNA is rejected.

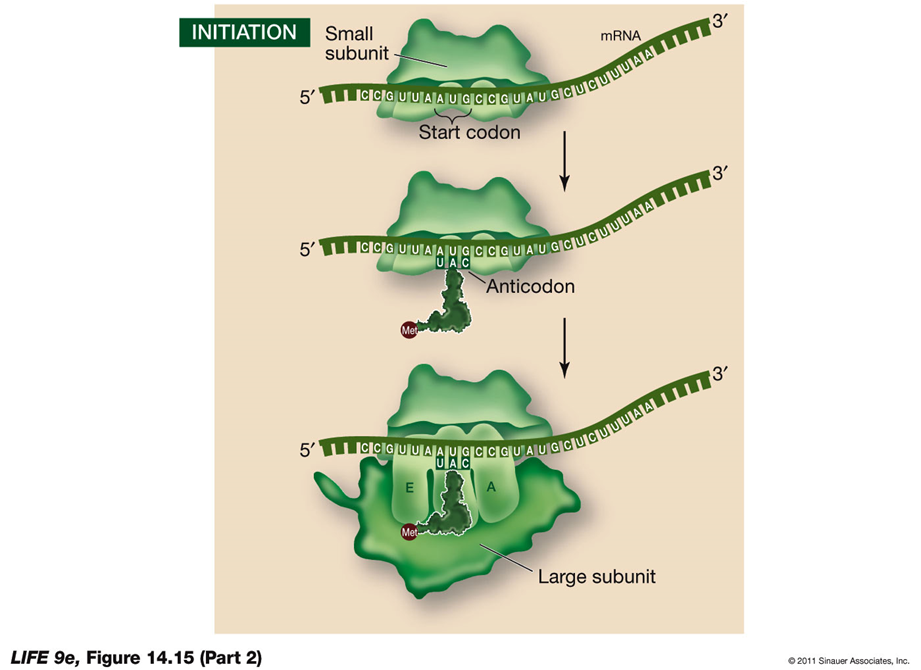

INITIATION:

Initiation of Translation

Initiation is the first step in the translation process, where the components necessary for protein synthesis come together to form the initiation complex.

Steps in Initiation:

Initiation Complex Formation:

A charged tRNA and the small ribosomal subunit bind to the mRNA.

Prokaryotes:

In prokaryotes, the rRNA of the small ribosomal subunit binds to an mRNA recognition site located "upstream" of the start codon.

Eukaryotes:

In eukaryotes, the small ribosomal subunit binds to the 5′ cap of the mRNA and moves along the mRNA until it reaches the start codon.

Start Codon (AUG):

The mRNA start codon is AUG, which codes for the amino acid methionine. Methionine is the first amino acid incorporated into the nascent protein and may be removed after translation is complete.

Large Ribosomal Subunit:

The large ribosomal subunit joins the initiation complex, positioning the charged tRNA in the P site.

Initiation Factors:

These proteins are responsible for the proper assembly of the initiation complex, ensuring that all components are correctly positioned to begin translation.

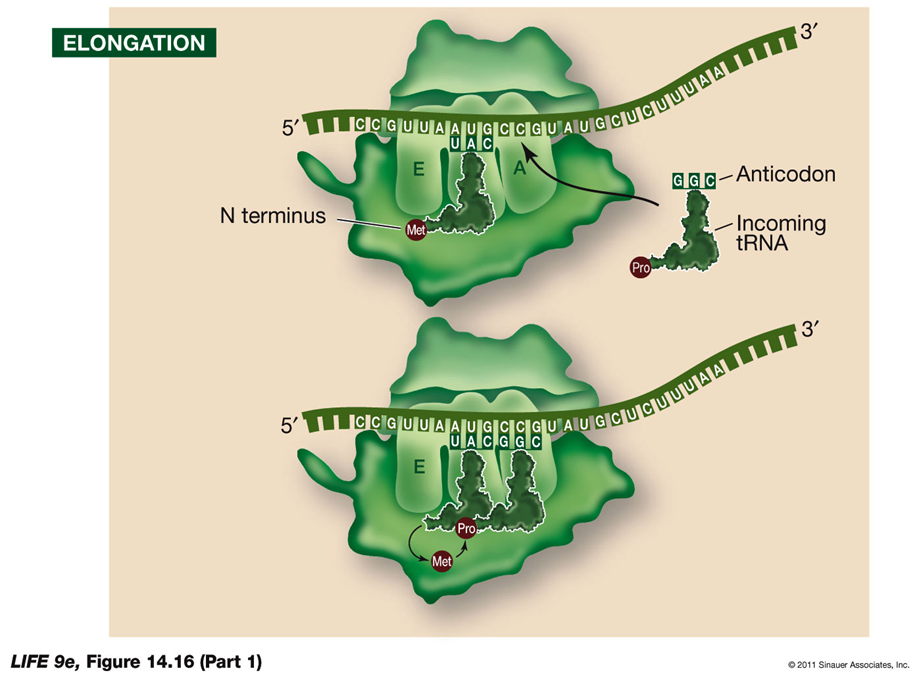

ELONGATION:

During elongation, the ribosome extends the polypeptide chain by sequentially adding amino acids.

Steps in Elongation:

Second tRNA Entry:

The second charged tRNA enters the A site of the ribosome.

Catalytic Reactions by the Large Subunit:

Breaking Bonds:

The large subunit catalyzes the breaking of the bond between the tRNA in the P site and its amino acid.

Forming Peptide Bonds:

It forms a peptide bond between that amino acid and the amino acid on the tRNA in the A site.

Peptidyl Transferase Activity:

The large subunit possesses peptidyl transferase activity, catalyzed by ribosomal RNA (rRNA).

If rRNA is destroyed, this activity stops, suggesting that rRNA is the catalyst, supporting the idea that catalytic RNA evolved before DNA.

tRNA Movement:

Once the first tRNA releases its methionine, it moves to the E site and dissociates from the ribosome, ready to be charged again.

Elongation Cycle:

Elongation continues with these steps, assisted by elongation factors. Each cycle adds a new amino acid to the growing polypeptide chain.

Release Factor:

Stop Codons:

Stop codons (UAA, UAG, UGA) do not code for a tRNA. Instead, they signal the release factor to bind.

The release factor transfers the growing polypeptide chain onto itself, causing the chain to be released.

This leads to the dissociation of the entire ribosomal complex, concluding translation.

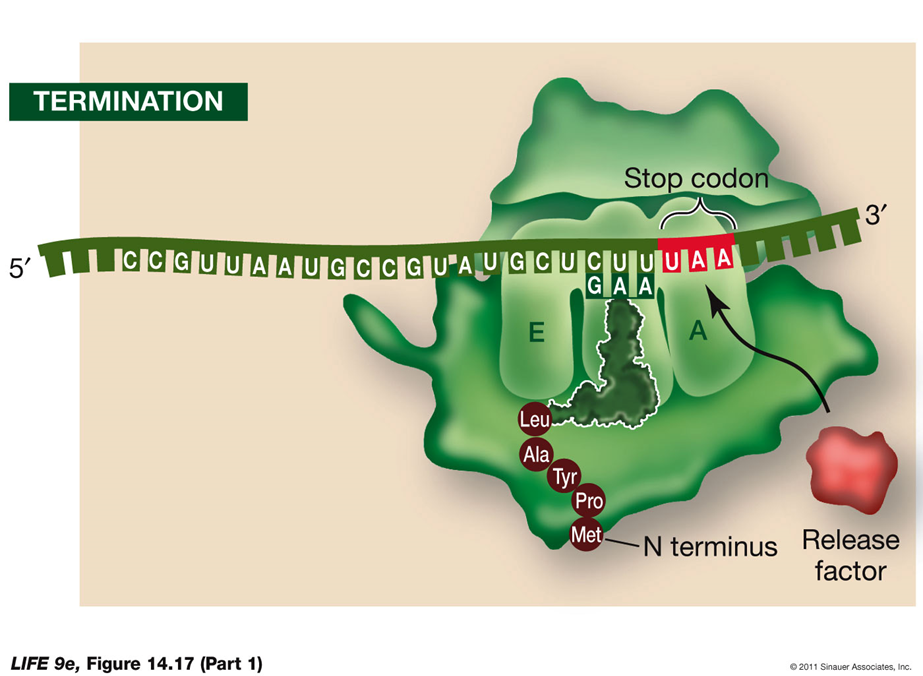

Termination of Translation

Termination Process:

Stop Codon:

Translation ends when a stop codon (UAA, UAG, UGA) enters the A site of the ribosome.

The stop codon binds a protein release factor.

Release Factor:

The release factor allows hydrolysis of the bond between the polypeptide chain and the tRNA in the P site.

This separates the polypeptide chain from the ribosome.

The last amino acid added to the polypeptide chain is at the C terminus.

Polyribosomes:

Multiple Ribosomes:

Several ribosomes can work simultaneously on a single mRNA strand, translating it into multiple copies of the polypeptide.

A strand of mRNA with associated ribosomes is called a polyribosome, or polysome.

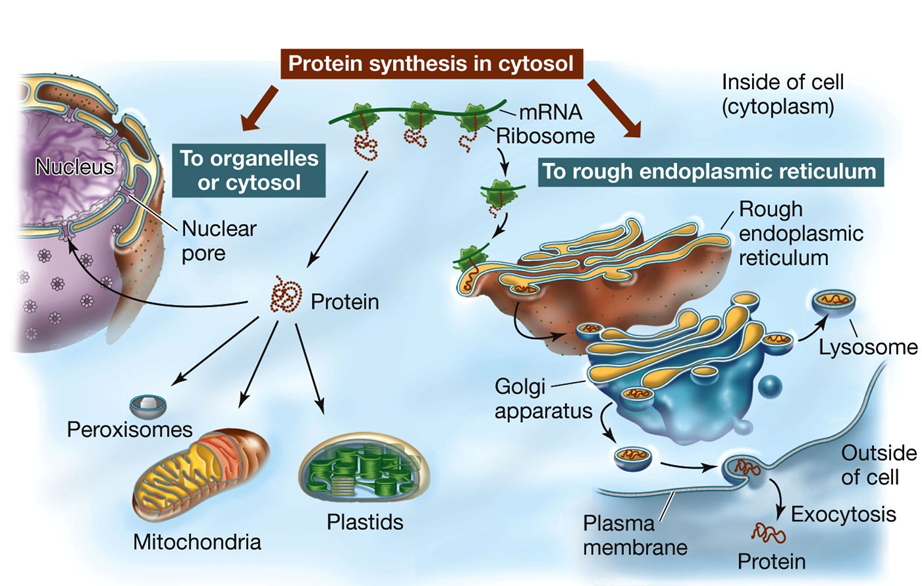

Posttranslational Aspects of Protein Synthesis Polypeptide Folding and Function:

Emerging Polypeptide:

The newly synthesized polypeptide emerges from the ribosome and begins to fold into its three-dimensional shape.

Proper folding is crucial for its function, allowing it to interact with other molecules.

Signal Sequence:

The polypeptide may contain a signal sequence indicating its destination within the cell.

The amino acid sequence provides instructions on whether the polypeptide should be sent to an organelle or remain in the cytosol.

These steps ensure that the polypeptide is correctly processed and directed to its appropriate location, enabling it to perform its intended functions within the cell.

Posttranslational Protein Targeting

Signal Sequences and Docking Proteins

Binding to Receptor Proteins:

The conformation of signal sequences allows them to bind to specific receptor proteins, known as docking proteins, on the outer membranes of organelles.

Channel Formation:

The receptor forms a channel through which the protein can pass into the organelle.

During this process, the protein may be unfolded by chaperonins to assist its passage.

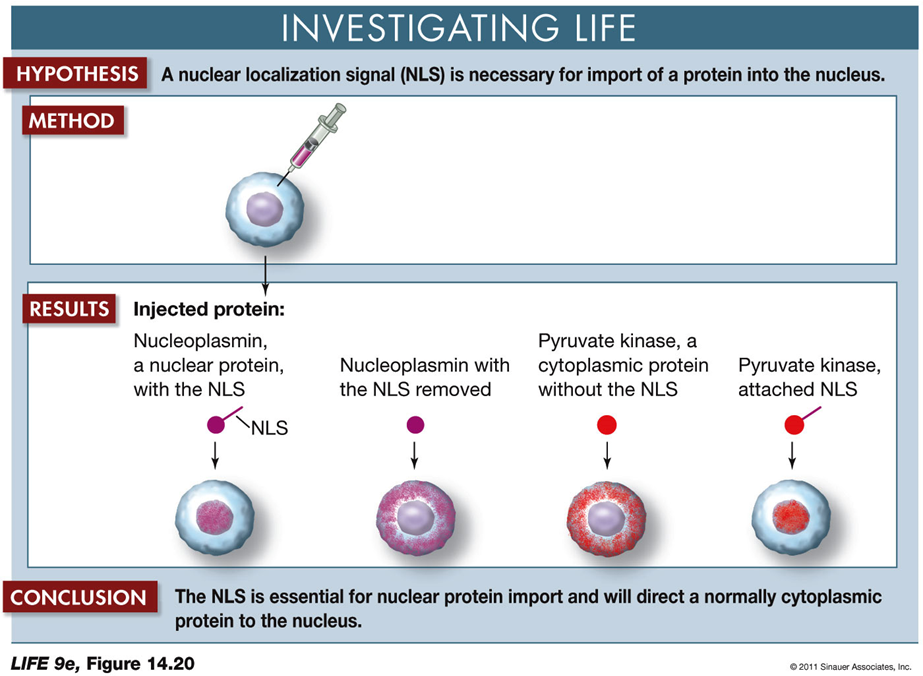

Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS)

Directing Polypeptides to the Nucleus:

A nuclear localization signal (NLS) directs the polypeptide to the nucleus.

Experimenters have shown that if the NLS is attached to a protein, the protein will enter the nucleus, even if it is normally found in the cytoplasm.

These mechanisms ensure that proteins are correctly targeted to their proper cellular locations, allowing them to function effectively. The ability to experimentally manipulate signal sequences provides insights into protein localization and function.

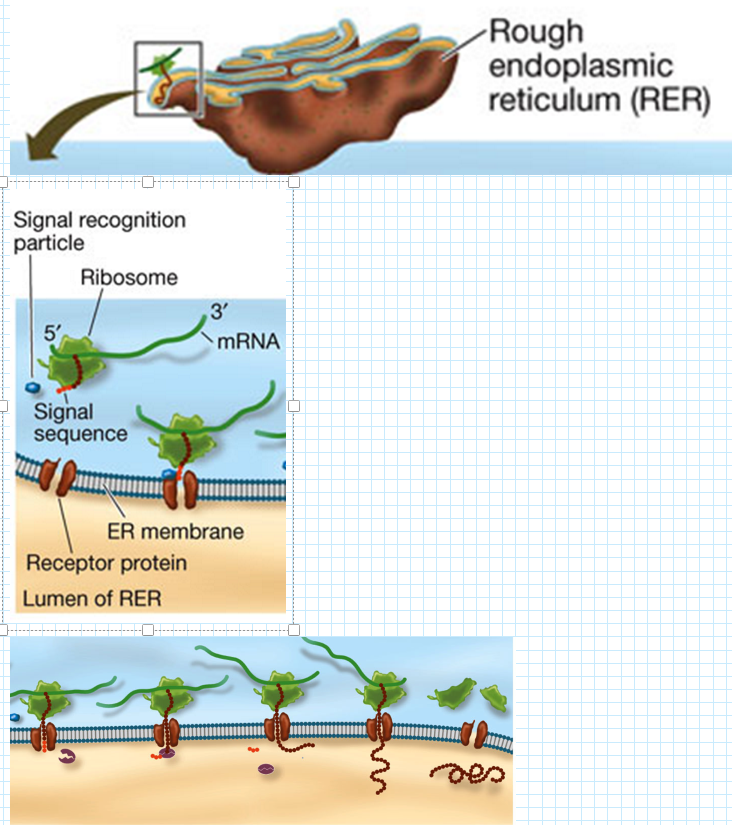

Posttranslational Targeting to the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER)

Steps for Proteins Sent to the ER: (Signal - Ribosome - Push)

Signal Sequence Binding:

The signal sequence binds to a signal recognition particle (SRP) before translation is complete.

Ribosome Attachment:

The ribosome, along with the SRP-bound signal sequence, attaches to a receptor on the ER membrane.

Polypeptide Translocation:

As translation continues, the growing polypeptide chain is either inserted into the ER membrane or passes through a channel into the ER lumen.

Signal Sequence Removal:

Once the polypeptide is inside the ER, an enzyme removes the signal sequence.

Nuclear localization signal (NLS) in protein import into the nucleus

Hypothesis:

A nuclear localization signal (NLS) is necessary for the import of a protein into the nucleus.

Method:

Different proteins are injected into cells to observe their localization.

Results:

Nucleoplasmin with NLS: The protein is found inside the nucleus.

Nucleoplasmin without NLS: The protein remains outside the nucleus.

Pyruvate Kinase (cytoplasmic protein) without NLS: The protein stays outside the nucleus.

Pyruvate Kinase with NLS attached: The protein is located inside the nucleus.

Conclusion:

The NLS is crucial for directing proteins to the nucleus. Proteins without this signal remain in the cytoplasm, while those with the NLS are imported into the nucleus.

Implications:

This experiment demonstrates the importance of the NLS in protein targeting and provides insights into how proteins are selectively transported within cells.

Posttranslational Targeting and Protein Modifications

If the Protein Enters the ER Lumen:

Signals for Protein Destination:

Amino Acid Sequences: These sequences allow the protein to stay in the ER.

Sugars Addition (Glycosylation):

Glycoproteins end up at the plasma membrane, lysosome, vacuole (in plants), or are secreted.

Protein Modifications:

Proteolysis:

The cutting of a long polypeptide chain into final products by enzymes known as proteases.

Glycosylation:

The addition of sugars to form glycoproteins, which is crucial for proper folding, stability, and cell signaling.

Phosphorylation:

The addition of phosphate groups catalyzed by protein kinases.

Charged phosphate groups can change the protein's conformation, affecting its activity and function.

These modifications and targeting mechanisms ensure that proteins are correctly processed and directed to their appropriate cellular locations, enabling them to perform their intended roles.

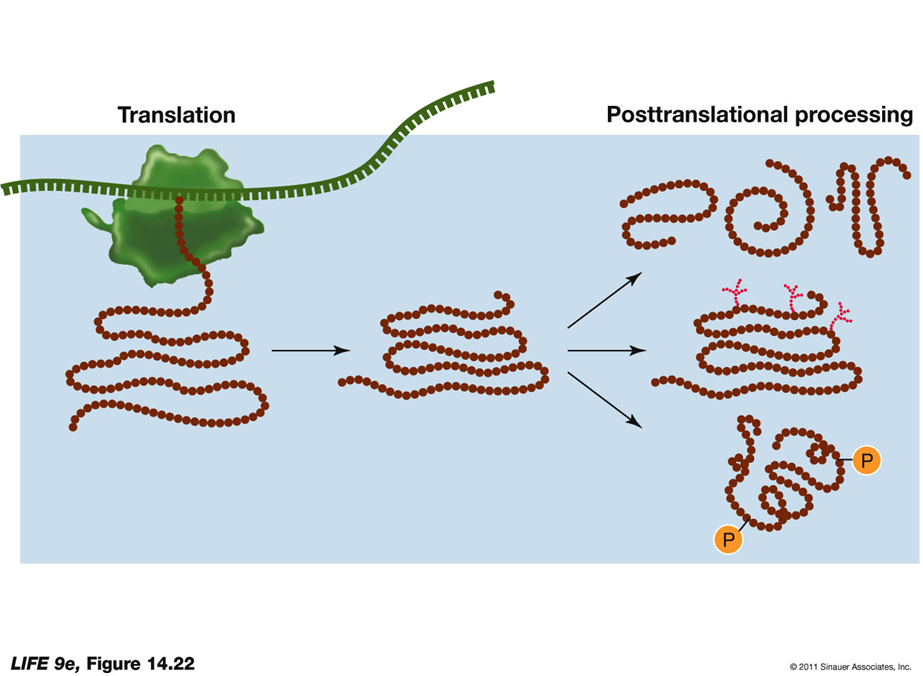

POST TRANSLATIONAL PROCESSING DIAGRAM:

DNA CLONING