Developmental: Week 8: Gender Identity & Sexuality in Neurodevelopmental conditions

1/54

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

55 Terms

Historical view of gender, sexuality & neurodevelopmental conditions

Historical view: Individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions as "asexual" or "childlike"

Led to a lack of research and clinical attention

Ethical concerns limited research

Informed consent? Vulnerability? Exploitation?

Biases hindered early studies

Example: focus on victimisation

Moving forwards

focus on sexual education, consent and healthy relationships

studies on the impact of neurodevelopmental conditions on sexual development and expression

research on gender identity and sexual orientation within neurodivergent populations

emphasis on the need for tailored support

most research focuses on…

Most research focuses on autism- very little on ADHD and practically none on WS and DS

The basics: sexuality

sexual attraction: refers to who a person is physically, romantically and/or emotionally attracted to

sexual identity: how a person identifies their sexual attraction and orientation

hetero, bi, asexual, pan, gay

sexuality is divers and can be fluid: meaning it may change over time

cultural and societal norms play a significant role in shaping how sexuality is understood and expressed

sexual development

childhood (0-12)

body awareness, gender role exploration, early understanding or relationships

adolescence (13-19)

puberty, sexual identity formation, early romantic experiences

adulthood (20+)

continued exploration, intimacy & relationship development, lifelong learning about sexual health & expression

sexual orientation

Sexual orientation typically emerges between middle childhood and early adolescence

UK 2021 census

89.4% of the general population identify as heterosexual

3.2% aged 16 and over identified as LGB+.

1.5% identify as gay or lesbian

1.3% identify as bisexual

0.3% identify as another sexual orientation

Autism & sexuality- Weir et al, 2021

Anonymous, self-report survey

1,183 autistic and 1,203 non-autistic adolescents and adults (aged 16-90 years)

8 times more likely to identify as asexual and ‘other’ sexuality than their non-autistic peers

autistic men are 3.5 times more likely to identify as bisexual

autistic women are 3 times more likely to identify as homosexual

ADHD & Sexuality

Research suggests that women with ADHD are more likely to have had homosexual experiences (Young & Cocallis, 2023)

However, generally, individuals with ADHD do not differ from neurotypical peers in their self-reported sexual orientation

BUT the potential to show more hypersexual behaviours (Hertz et al., 2023; Soldati et al., 2021

ADHD features and sexuality

impulsivity → risky sexual behaviour

dopamine → sensation seeking and reward seeking

inattention → distractibility and difficulty focussing

sensory sensitivities → discomfort and repelled

Gender: the basics

"sex" vs "gender"

"Sex" typically refers to biological attributes, such as chromosomes, hormones, and anatomy

"Gender" is largely understood as a social construct:

Involves the norms and expectations that societies create around what it means to be a "man," "woman," or other gender identities

These norms vary across cultures and change over time

Quick recap of PSY2004

Kohlberg's Stages:

Stage 1 (2-3 years): Gender Identity based on appearance.

Stage 2 (4-5 years): Gender Stability over time, still appearance-based.

Stage 3 (6-7 years): Gender Constancy across changes.

Nature vs Nurture

Biological Factors: Hormones (androgens) influence development. Intersex conditions and transgender/twin studies are relevant.

Social Cognitive Theory: Gender development involves personal, environmental, and behavioral factors.

Gender Similarity Hypothesis:

Genders are more alike than different in most variables

PSY1004: key terms

As children develop, they learn to perform behaviours associated with their gender.

Gender-typing and gender expression are the processes by which adopt observable behaviours in line with our construction of gender.

gender-typed preferences and behaviours result from the combined influence of biological, psychological and sociocultural processes (Leaper, 2013) i.e. biopsychosocial model

Gender identity

Gender is a complex interplay of social, cultural, and personal factors, distinct from the biological concept of sex

Gender identity is an individual’s sense of their own gender

it may or may not align with the sex they were assigned at birth

gender identity exists on a spectrum, and people may identify as male, female NB or other identities

gender diversity: experiencing of aspects of your gender as different from your assigned sex at birth

gender diversity can result in gender incongruency where a person’s gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth

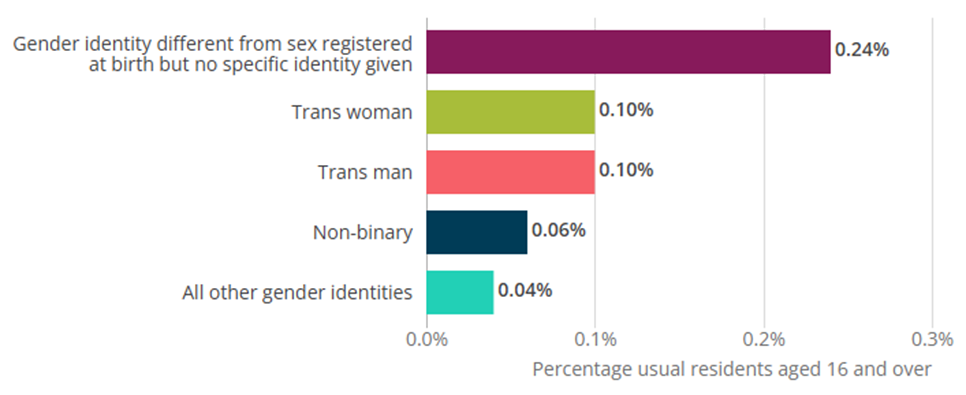

The general population

Survey-based research estimates that as many as 1% to 2% of adolescents identify as gender diverse (i.e. gender nonconforming or transgender; Rider et al., 2018)

In the 2021 UK Census 0.5% of the general population indicated that their gender identity differed to their sex registered at birth

Gender dysphoria

People may experience discomfort or distress when their assigned sex is different from the gender they identify with

This is known as gender dysphoria

In the UK, transgender people must be assessed for gender dysphoria before physical interventions such as gender affirming hormones and surgery can be accessed on the NHS

NB. Not all trans people have dysphoria

While many transgender individuals do experience gender dysphoria, it's not a universal experience, and some transgender individuals may not experience it at all. Cisgender people can also experience dysphoria.

DSM-5-TR: children

An incongruence between experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, lasting 6m +, with 6+ of the following (must have first criterion):

A strong desire to be or an insistence that they are the other gender

In boys (assigned gender), a strong preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong preference for wearing masculine clothing and a strong resistance to feminine clothing

A strong preference for cross-gender roles in make-believe play

A strong preference for toys, games or activities stereotypically used by the other gender

A strong preference for playmates of the other gender

In boys (assigned gender), a strong rejection of masculine toys, games, and activities and a strong avoidance of rough-and-tumble play; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong rejection of feminine toys, games, and activities

A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy

A strong desire for the physical sex characteristics that match one’s experienced gender

DSM-5-TR: adolescents & Adults

A marked incongruence between experienced/ expressed gender and assigned gender, lasting 6m+, at least 2 of the following:

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and primary and/or secondary sex characteristics (or in young adolescents, the anticipated secondary sex characteristics)

A strong desire to be rid of one’s primary and/or secondary sex characteristics because of a marked incongruence with one’s experienced/expressed gender (or in young adolescents, a desire to prevent the development of the anticipated secondary sex characteristics)

A strong desire for the primary and/or secondary sex characteristics of the other gender

A strong desire to be of the other gender (or alternative gender different from assigned)

A strong desire to be treated as the other gender (or alternative gender different from one assigned)

A strong conviction that one has the typical feelings and reactions of the other gender (or alternative gender)

Gender Diversity in autism

the first systematic study was led by de Vries et al (2010): investigated the incidence of autism in children and adolescents referred for gender diversity services

7.8% of the sample met strict diagnostic criteria for autism - 10 x higher than the prevalence of autism in the general population at that time

Strang et al, (2018): identified studies of gender diverse and transgender youth that included only clinical autism diagnoses or autism diagnosed through comprehensive methods

in all 7 available studies rates of clinical diagnoses were significantly greater compared to the general population

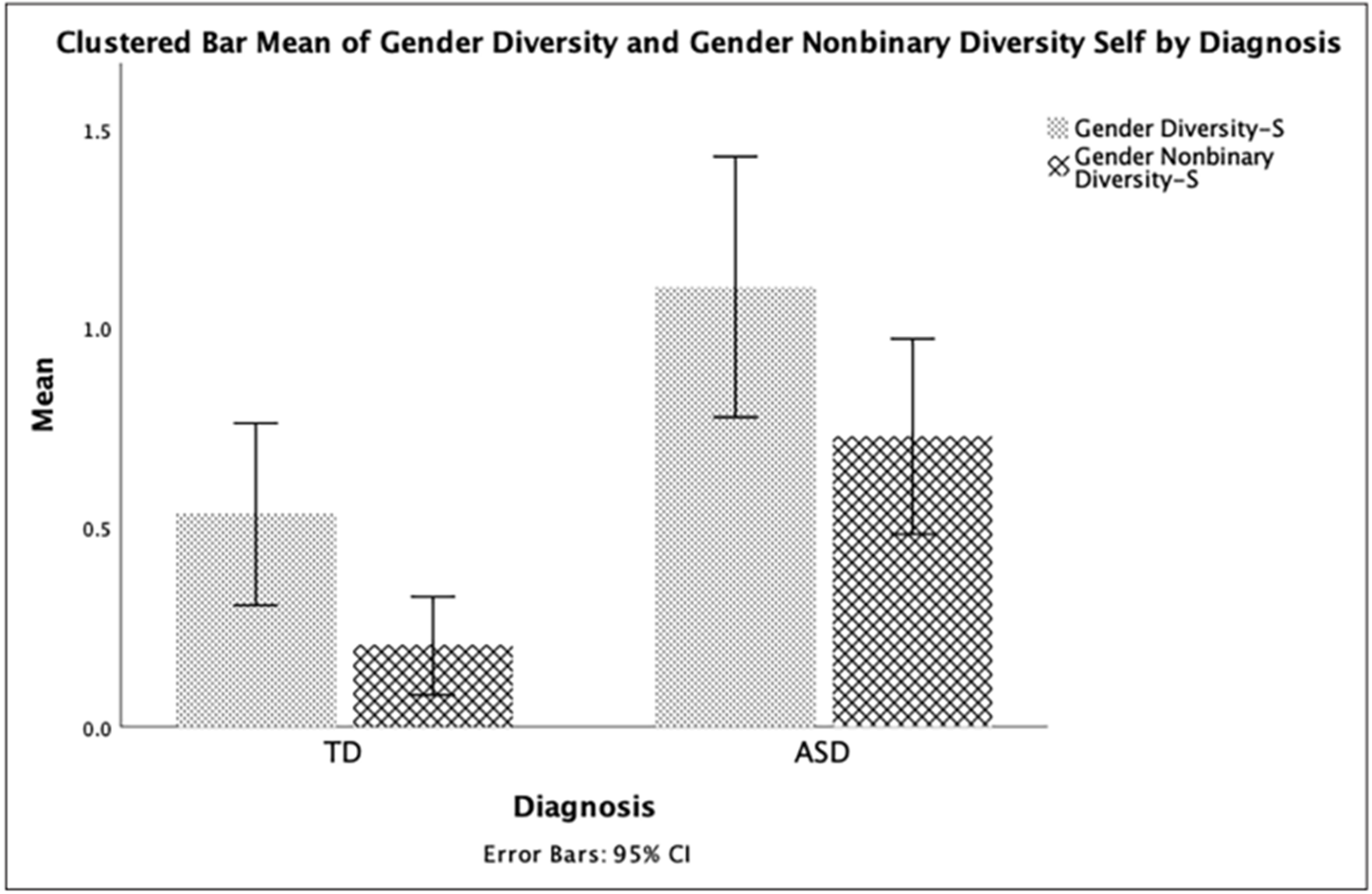

Corbet et al., 2023

used the gender diversity screening questionnaire (self report and parent report)

244 children (140 autism and 104 neurotypical)

self-report: autistic children showed higher gender diversity (both NB and binary) than neurotypical children

parent-report: a significant difference in gender diversity between the groups on body incongruence

underscores “the need to better understand and support the unique and complex needs of autistic children who experience gender diversity”

Gender diversity & ADHD

Very limited studies look at ADHD

Warrier et al., 2020 – Transgender & Gender diverse individuals had elevated rates of ADHD

Prevalence rate of 8.3% in children and adolescents referred for gender care (Holt et al., 2016)

Prevalence rate of 4.3% in TGD adults (Cheung et al., 2018).

Ignatova et al., 2025:

10,277 ADHD & Transgender early adolescents (12-13 years)

Data from the longitudinal Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study

Methods: “Are you transgender?” Yes (TG), no (CG) or maybe (GQ)

Gender diverse individuals showed higher levels of ADHD traits

Results reduced when controlling for stress

Lived experience: autistic and transgender- Cooper et al., 2022

21 autistic adults took part in semi-structured interviews

All participants identified as transgender and/or non-binary

Main Findings:

Distress due to their bodies not matching their gender identities, while managing complex intersecting needs

Societal acceptance of gender and neurodiversity

Barriers in accessing healthcare for their gender needs

Tension between need to undergo a physical gender transition versus a need for sameness and routine

Cooper et al., (2022): Positive experiences

“We see the world differently” (Participant 22), referring to the idea that being autistic allows one to step outside of societal norms and follow your own path

“I have never tried to fit in with people, or very rarely. So whilst now my gender presentation is very stereotypically male, there are some things that I do are intentionally more feminine, but I don't care” (Participant 12)

“Then after having a [autism] diagnosis a lot more of my experiences have come to light again and there's things that I do actually make me really uncomfortable or things that really don't suit me that I have edited to ignore a long time ago.” (Participant 17), found the diagnosis comforting and this allowed new coping strategies to be implemented

DSM-V-TR Autism

“Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement)”

Dysphoria & Sensory sensitivities

Cooper et al., 2022:

Some participants described ‘sensory dysphoria’ - distress linked to sensory experiences

Wearing uncomfortable fabrics and shapes associated with girls’ clothes

Sensory challenges of puberty including periods, and growing facial hair

‘I was stuck between having really bad gender dysphoria not wearing a binder or feeling really uncomfortable sensory wise.’

Biological theories

Prenatal Hormone Exposure:

Variations in prenatal hormone exposure could contribute to differences in how individuals perceive and experience gender

Brain Structure and Function:

Differences in structure and function could influence how individuals process and internalise social constructs like gender

Differences in brain regions involved in social cognition and self-perception might play a role

Increased self-identification

Autistic individuals may be less influenced by societal norms and expectations surrounding gender & sexuality

Leading to a greater likelihood of expressing their authentic gender or sexual identities, even if it deviates from societal norms

In other words, they may be less likely to suppress or conform to traditional gender roles or sexual identities due to social pressures

Differences in social cognition & sensory processing

Systemising and Pattern Recognition:

a more analytical approach to gender, breaking down its components and questioning traditional norms

Intense Focus and Special Interests:

Increased depth, leading to a more profound understanding of their own identity & less influence from outside sources

Sensory sensitivities/sensation seeking:

Certain clothing textures or social environments associated with specific genders might be intensely uncomfortable

Preference for certain gendered presentations due to the sensory input it provides

Gender Identity, Sexuality & Down Syndrome

Limited to no studies investigating gender diversity in Down Syndrome

Parent-report regarding more general views of sexuality in DS

No studies directly speaking to individuals with DS

Instead, studies focus on the need for and improvement of sexual education for individuals with DS

Sexual education in DS

The World Health Organization advocates for SE as a human right

BUT adolescents and young adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities are frequently excluded

Often focuses on safety and abuse prevention rather than a holistic approach

healthy relationships, consent, and sexual fulfilment

Need to work with these individuals to develop more accessible and effective SE programs

Schmidt et al., 2021

Improving the accessibility of sexuality education (SE) for individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities.

Qualitative data collection through interviews and focus groups

Individuals, parents, healthcare providers, and educators.

Modalities

Educational guides

Visuals

Videos

Universal Design for Learning

Direct, explicit instructions

Additional:

Role-playing & modelling

Open communication

Importance of parental support and education

Settings:

one-to-one

small groups

combination

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

UDL adapts education to fit diverse learner needs

The 3 UDL Principles

Representation (the "what"): Offer information in varied formats (e.g., visual, auditory).

Action/Expression (the "how"): Provide different ways for learners to interact and express themselves.

Engagement (the "why"): Increase motivation through choice, relevance, and collaboration.

UDL in Sexuality Education

UDL makes SE accessible and engaging for all

Cooper et al, abstract

Autistic people are more likely to be transgender.

Some transgender people experience gender dysphoria.

In this study, 21 autistic adults were interviewed about their experience of incongruence between their gender identity and sex assigned at birth, and any associated distress.

Participants experienced distress due to living in a world which is not always accepting of gender- and neuro-diversity.

Participants described barriers in accessing healthcare for their gender needs.

Some participants felt being autistic had facilitated their understanding of their gender identity.

Other participants described challenges such as a tension between their need to undergo a physical gender transition versus a need for sameness and routine.

Cooper et al, lay abstract, Warrier et al

Warrier et al. (2020) found that that transgender adults were 3.03–6.36 times more likely to be autistic than cisgender people.

This may not be unique to autism; systematic reviews and large-scale studies have indicated that ADHD may also be more common in transgender individuals compared to cisgender individuals

Reading- Gender dysphoria diagnoses:

Some transgender individuals experience gender dysphoria: DSM-5: a significant incongruence between an individual’s gender identity and assigned gender leading to distress or impairment.

The ICD-11 diagnostic criteria amended it to focus less on distress, broadening the criteria and labelling it gender incongruence.

The criteria for gender incongruence involve a marked and persistent mismatch between an individual’s assigned sex and gender, frequently leading to a desire to transition gender.

In the UK, an assessment of gender dysphoria must be made before physical interventions can be accessed, and so the experience of distress linked to this incongruence is key to accessing healthcare.

Reading- Support for gender dysphoria and contributors to distress beyond gender dysphoria itself

In the UK, individuals can access NHS gender clinics for psychological support and physical treatments including hormone treatment and gender confirmation surgery.

Adults with gender dysphoria undergoing physical interventions improves psychological well-being and quality of life, but higher quality evidence is needed.

Furthermore, the rates of autism of participants in these studies are not known, and so research investigating the well being of autistic people following physical gender transition is needed.

Experiences not in DSM-5 gender dysphoria criteria can contribute to distress in transgender adults.

These include social isolation due to being transgender, being misgendered, and cognitive and emotional processes linked to experiences of transphobia.

These experiences can be understood in the context of gender minority stress theory, which refers to experiences of stigma and discrimination due to being transgender contributes to mental health difficulties.

Reading- stress due to autistic identity

Given that autistic people also experience minority stress due to their autism identity, it is likely that the experiences of being autistic and being transgender intersect in clinically meaningful ways.

Mental health problems are more common in autistic people and in transgender individuals.

There is emerging evidence that being both transgender and autistic is associated with yet higher rates of mental health problems.

Reading- autistic and transgender individuals past research

There have been 2 qualitative studies on the lived experience of gender diversity & autism and 2 community-based participatory design papers describing a clinical intervention for young autistic people who are transgender.

Coleman-Smith et al. (2020) investigated the lived experience of gender dysphoria in 10 autistic adults in the UK

used Grounded Theory

found an overarching theme ‘conflict Vs congruence’.

A study with 22 transgender autistic youth found that participants reported a strong need to live in their affirmed gender.

Participants emphasised that their gender identity would persist, and they experienced gender dysphoria, but felt no need to conform to gender stereotypes.

Participants felt that being gender and neurodiverse brought challenges. Their gender identity was questioned due to their autism.

These studies demonstrate that autism may affect the phenomenology of gender dysphoria and impact access to gender transition services.

Reading - method: methodological approach

IPA is a qualitative research method which focuses on a specific phenomenon, such as gender dysphoria, and aims to distil the essence of this experience.

IPA emphasises the individual lived experiences of participants, and focuses on how each participant understands and makes sense of their experiences of a particular phenomenon.

This approach acknowledges that the researcher will bring their own experiences and expertise to the analysis, and this must be reflected upon by keeping a reflexive attitude and maintaining a keen awareness of any researcher biases within the analytic process.

IPA has been identified as an important tool in autism research due to its focus on the lived experience and meaning to autistic individuals, and in this study, we aimed to stay close to the meaning-making of the individual in order to offer insights into participant experiences, while remaining aware of our identities as non-autistic researchers.

IPA achieves this through careful analysis of themes in each individual transcript, before moving on to develop themes in the next transcript.

This process continues until each individual set of themes has been collated, and then themes are developed across the data set.

Reading: participants

21 adults who had a clinical diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder.

All participants identified as transgender and/or non-binary and had experienced distress in relation to the incongruence between their gender identity and sex assigned at birth, which they discussed with a health professional.

Participants therefore may or may not have met DSM-5 criteria for Gender Dysphoria.

The sample was relatively homogeneous, in that all participants had an autism diagnosis and experience of gender dysphoria.

A larger number of participants were invited to take part to ensure a range of gen der identities, ages, stages of transition and geographical location in participants, following advice from the patient and public involvement group who were all autistic transgender adults.

Some of the community group sample invited other group members, (snowball sampling).

Of those who identified as non-binary/genderqueer; five were AFAB and one was AMAB.

Of those with complete data, 7 requested support for gender dysphoria and then received an autism diagnosis, and 9 had an autism diagnosis before requesting support for gender dysphoria.

Reading- methods: procedure

In the NHS context, clinicians within each recruitment site spoke to potentially eligible participants about the research project during routine clinical appointments.

This clinician assessed participant eligibility for the study, including checking for a confirmed autism diagnosis and experiences of gender dysphoria, before gaining consent from the potential participant to give their contact details to the research team.

Participants who were recruited via other members of community groups made direct contact with the study team.

The research team assessed community group participants for their eligibility to participate, including confirmation of autism diagnosis by clinic letter from a qualified medical professional, before inviting eligible participants to take part.

Participants were invited to meet with a researcher either in-person or online to give fully informed consent.

After, participants completed a questionnaire collecting information about age, gender identity, current sexual orientation and journey through the health service for support around autism and gender dysphoria.

Next, participants were interviewed by the first author about their experience of distress linked to gender incongruence and of seeking help for this in the NHS.

Interviews took place Dec 2019- October 2020 and lasted around 66 min (range = 39–104 min).

The topic guide covered:

earliest experiences of gender dysphoria;

experience of being autistic and having gender dysphoria;

interaction of gender dysphoria, autism and mental health;

seeking help for gender dysphoria and autism adaptations in services.

open questions were used as much as possible.

However, some needed autism adaptations to fully respond to questions, including writing down responses (n = 3), having someone else in the room to support them (n = 1), and for all participants, the interviewer used a flexible interview style including closed prompt questions.

Some participants took more prompting and were less able to describe their feelings; however, this formed part of the analysis in itself.

Interviews were audio recorded using a digital recorder and the audio recording was sent to a professional transcription company and transcribed using an intelligent verbatim method.

Participants were reimbursed with a £25 shopping voucher and sent a debrief form following participation

Reading- community involvement

A group of transgender autistic adults (n = 6) were consulted and formed an involvement group for the research project.

These individuals were identified through an NHS run peer support group for autistic transgender adults, and could contribute by giving their opinions on the suggested research question and methods.

They also helped to ensure study materials were adapted for autistic adults, reviewing the information sheet and topic guide for the interview.

Finally, they reviewed the final analysis and theme names, and com mented on how the theme names and descriptions could be made accessible to the autistic community

Reading- results: Making sense of distress and finding my identities

The first superordinate theme describes the discomfort and distress that all participants experienced, and had three sub themes. This discomfort was experienced in participants’ bodies and in their sense of self, linked to their multiple identities and life experiences.

Reading- results: Experiencing and describing body distress.

This theme referred to the distress participants felt having a body that did not match their gender identity

all participants described this, but many struggled to articulate it.

Participants spoke of a range of negative emotional responses to their bodies including depression, anxiety, anger and disgust, with some dissociating from their bodies.

A non-binary participant described experiencing ‘an estrangement’ from their body; I feel most comfortable with broader shoulders, and more body muscle . . . with an androgynous, strong shape to me. I go to some effort to hide if I want others to treat me a certain way, which is tedious.

Some participants described puberty as being particularly distressing as their body developed in an unwanted way.

For example, a trans male participant: ‘I kind of grew up like a boy so puberty was very distressing, like in my brain I wasn’t expecting it to happen’.

For many participants, these experiences of embodied distress were difficult to articulate verbally.

Some participants used concrete, behavioural markers when describing their experience of gender-related distress: ‘. . . it’s quite unpleasant. There were situations where I was going to cause harm to my family’, while others described their gender dysphoria in more abstract terms: ‘I’m sort of nowhere. Sort of disappeared . . . It makes me feel sad’ (5), showing challenges in communicating this bodily experience.

Reading: Results: Making sense of who I am

This theme described the importance participants placed on understanding their identities, and the sense of unease when they did not have this understanding.

This led to feelings of discomfort and frustration linked to the person’s broader sense of self, going beyond bodily experiences.

Some described feelings of discomfort that they needed an explanation for and realising they were transgender and autistic was important in gaining an understanding.

These realisations were comforting and allowed new strategies to be implemented to alleviate distress, such as participant 17 who stopped masking after a diagnosis

While some described the utility of labels and diagnoses for understanding the self, a few used different labels before settling on a transgender identity: ‘Yeah I went through a phase, “Well, if I can’t be a boy, then I’ll just be a butch lesbian”.

Reading: Results: intersecting and competing needs

This theme described the overlapping difficulties experienced which can required competing solutions.

Some participants described these needs as amplifying dysphoria, such as: ‘I think how intensely I process dysphoria is autism related’,

some felt they were entangled, while others conceptualised these struggles as separate to their gender dysphoria.

Many participants described multiple challenges that they faced which caused significant psychological distress. These included mental health needs, traumatic experiences and autism-specific difficulties such as being overwhelmed by sensory experiences.

Many described a clash between their autism and gender needs, causing additional distress. Some described ‘sensory dysphoria’; experiences of distress in their bodies linked to sensory experiences including the sensory challenges of puberty like periods, such as dealing with the smell of blood, and growing facial hair.

Many reported finding change stressful, alongside a strong need to undertake a social and/or physical gender transition, and that this caused tension.

Concrete thinking linked to autism made it harder for some participants to understand their gender, such as being NB ‘I hate trying to be a girl but I have to force myself to be a man because there’s only two options’.

Some felt that autism helped with understanding their gender such as being autistic allows one to step outside of societal norms to follow one’s own path.

Reading: Results: Mismatch between needs as an autistic trans person and society

The next superordinate theme had three sub-themes:

doing gender

struggle of being different

battle for support.

This theme centred on participant experiences of living in their bodies, gender identities and with their autism features within the social world not always accepting of differences.

Most had needs not easily met in society. It was important that their gender identity and autism identity was affirmed by others, and they were able to undergo a gender transition despite the barriers they experienced.

Reading: Results: Mismatch between needs as an autistic trans person and society: Gender as social behaviour.

Individuals experienced their gender identity through the eyes of others, which meant learning how others thought about gender, how their experience fit with these gender norms, and ensuring their individual gender expression would stop others from misgendering them.

Some felt that gender was a social expectation they didn’t get, through being unaware of gender as a concept or being confused by it.

Participant 20 explained how this linked to their autism: ‘Being autistic is like everybody else has got the rulebook and you didn’t, so gender would come into it because it was in the rulebook’.

Others felt comfortable in their non-conformity: ‘I have never tried to fit in with people, or very rarely. My gender presentation is very stereotypically male, but I do some things intentionally more feminine’.

Some felt affected by gender stereotypes linked to autism: ‘people who see me as female may not necessarily pick up on my autistic traits as much’, referring to the way in which autistic traits can be perceived as being stereotypically male.

For some, it is difficult to know what others thought about their gender- ‘I’d get too aware of how other people were perceiving me, to the point where I’d almost lose myself because I’m imagining their perceptive’

Reading: Results: Mismatch between needs as an autistic trans person and society: struggles of being different

This described the challenges of autistic people living in a cisnormative world and where the differences associated with autism and being transgender can be perceived negatively.

Participants struggled against this, sometimes experiencing a desire to fit in to mitigate these negative social experiences, which could be challenging given their differences in gender and social expression.

Many described periods where they were ostracised, bullied and socially isolated due to their identities.

Some described having difficulties in social situations as a result of autism and their different gender expression, but autism was typically the main cause of social difficulties:

‘being autistic, people were too preoccupied to think about my gender so I never really faced any problems regarding that’.

Resulting from this, some referred to a sense of shame: ‘You feel you’re kind of failing as a person that doesn’t fit anywhere and you just want to retreat’.

Some spent significant time worrying about how they were perceived by others.

Reading: Results: Mismatch between needs as an autistic trans person and society: battle for support

This theme summarised the struggle to be acknowledged in their identities by people in positions of power, primarily professionals in health, education and social care settings.

This theme also refers to most participants’ desire to communicate about gender and undergo a transition, but that features of autism could create barriers to this.

Sometimes, interactions at a gender clinic, or with mental health professionals, were a battle to get the support the individual wanted.

Many spoke of significant barriers to accessing a gender clinic due to their autism.

Where participants did access a gender clinic, they did not always feel that their autism was considered, and ‘had to appear as neurotypical as possible’ to gender clinicians.

Others felt that adaptations were made: ‘once I had a consistent clinician, it got a lot better’ or communication adaptations: ‘giving us, I wouldn’t say a prompt but did you feel like this, or did you feel this?’.

Participant 16 described difficulties with the uncertainty of processes around attending gender clinics: It was very difficult because there’s no set rules especially with transitioning there’s no checklist or timescale.

Participant 2 struggled with the physical environment at the gender clinic: they had these bright lights that buzz, and the clock’s ticking and it bombards you with the sensory stuff.

Reading: Results: Additional themes

Themes which were endorsed by less than half the participants, but were of relevance, included that 5 participants’ vulnerability to abuse, with 2 linking this vulnerability to being both transgender and autistic.

For example, participant 1 described how before making any social transition, he thought of himself as a man, and did not consider that others would not see him that way, leaving him vulnerable to abuse:

‘this guy attacked me and I was in a very vulnerable place ‘cause I had no idea, I just saw myself as male’.

Two felt being autistic meant they spent more time researching gender identity, with participant 12 worrying that gender was a special interest, before concluding that it was not

Discussion

Autistic participants described their distress due to:

their gender identities not matching their bodies and struggle to articulate this experience

a need to understand their identities more broadly

manage complex and intersecting needs.

Participants faced difficulties in:

the social aspects of gender expression and societal norms around gender identity,

experienced distress when not treated as their gender by others

being autistic and living in a world not always accepting of gender- and neuro-diversity.

and experienced barriers in accessing healthcare for their gender needs.

It may be that the social communication differences characteristic of autism, and higher rates of alexithymia, increased the likelihood that their experiences were misinterpreted by clinicians. This may have led to the negative consultations with healthcare professionals.

Many spent time and energy trying to understand their identities. Uncertainty about identity was often linked to gender, but also extended to sense of self more broadly, and there was a need to make sense of their identity as an autistic person.

Discussion- stressors for those autistic and transgender

The experience of distress due to a mismatch between assigned and affirmed gender was concurrent with competing needs. Participants faced additional stressors, including:

a conflict between autism and gender needs,

other mental health needs and contextual stressors

such as abuse and trauma,

which contributed to increased distress and discomfort in the self.

The findings suggest that autistic people may be more likely to have multiple sources of distress which can increase the intensity of their existing gender dysphoria.

We identified some aspects of gender dysphoria which interacted with autism. Autism was seen as having a positive effect on the understanding of gender for some, facilitating awareness of gender identity. This is consistent with ideas of autistic people being resistant to social conditioning regarding gender and ‘gender defiance’ in autistic people.

There were also descriptions of increased challenges, such as distress due to competing needs for routine versus undergoing a gender transition.

Autistic people often have a preference for certainty, and some were distressed when they were uncertain about their identity.

Discussion- sensory sensitivities, social conventions, healthcare

Finally, sensory sensitivities characteristic of autism contributed to increased gender dysphoria.

For some, less intuitive understanding of social conventions led to not identifying with gender norms; this was freeing for some, frustrating for others expected to conform to gender stereotypes.

This fits with research with autistic women that found participants did not feel compelled to conform to gender norms.

Many participants felt let down by health services as they wanted their identities to be acknowledged, without them becoming barriers to autism, mental health or gender care.

Participants identified adaptations to improve their experience of healthcare. These ranged from differences in practicalities about organising appointments, changes to the clinic environment and changes in clinician communication.

These adaptations are similar to those recommended for psychological therapy with autistic people.

In line with recent findings that autistic transgender youth experience more executive functioning related barriers to accessing gender healthcare

Cooper et al- critical evaluation

A strength was the focus lived experience of participants who are frequently marginalised due to their identities as autistic and transgender.

Recruit participants from healthcare and community settings, with a range of gender journeys and stages of physical gender transition.

We ensured that the analysis stayed close to the meaning of gender dysphoria to participants, emphasising their individual experiences.

We carefully sampled adults who had a clinical autism diagnosis but who had broader experiences of distress around gender; as it is relevant to healthcare settings following WPATH (2012) standards of care, including in the UK, where a diagnosis of gender dysphoria is needed to access gender affirmation interventions.

A limitation was the larger sample size; the analysis had to move on more quickly from the individual analysis of each case to analysing themes across all cases.

Future research should investigate the inner experiences of transgender autistic people, with less focus on gender dysphoria, encapsulating a range of gender experiences, outside of diagnostic criteria.

Moreover, research with a focus on the development of a sense of gender identity and both gender conforming and non-conforming behaviours in autistic children and young people is needed to understand gender identity development more broadly in this population.

Clinicians working should be aware of the differences in the autistic experience of gender dysphoria and make adaptations so that this group can access appropriate healthcare and support