Developmental: Week 8: Gender Identity & Sexuality in Neurodevelopmental conditions

Core reading-

Cooper, K., Mandy, W., Butler, C., & Russell, A. J. (2022). The lived experience of gender dysphoria in autistic adults: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Autism, 26, 963-974.

Historical view of gender, sexuality & neurodevelopmental conditions

Historical view: Individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions as "asexual" or "childlike"

Led to a lack of research and clinical attention

Ethical concerns limited research

Informed consent? Vulnerability? Exploitation?

Biases hindered early studies

Example: focus on victimisation

Moving forwards

focus on sexual education, consent and healthy relationships

studies on the impact of neurodevelopmental conditions on sexual development and expression

research on gender identity and sexual orientation within neurodivergent populations

emphasis on the need for tailored support

Most research focuses on autism- very little on ADHD and practically none on WS and DS

Sexuality

The basics: Sexuality

sexual attraction: refers to who a person is physically, romantically and/or emotionally attracted to

sexual identity: how a person identifies their sexual attraction and orientation

hetero, bi, asexual, pan, gay

sexuality is divers and can be fluid: meaning it may change over time

cultural and societal norms play a significant role in shaping how sexuality is understood and expressed

Sexual development

childhood (0-12)

body awareness, gender role exploration, early understanding or relationships

adolescence (13-19)

puberty, sexual identity formation, early romantic experiences

adulthood (20+)

continued exploration, intimacy & relationship development, lifelong learning about sexual health & expression

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation typically emerges between middle childhood and early adolescence

UK 2021 Census

89.4% of the general population identify as heterosexual

3.2% of the population aged 16 and over identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or another sexual orientation (LGB+).

1.5% identify as gay or lesbian

1.3% identify as bisexual

0.3% identify as another sexual orientation

Autism & sexuality- Weir et al, 2021

Anonymous, self-report survey

1,183 autistic and 1,203 non-autistic adolescents and adults (aged 16-90 years)

Eight times more likely to identify as asexual and ‘other’ sexuality than their non-autistic peers

Sex differences in sexual orientation:

autistic men are 3.5 times more likely to identify as bisexual than non-autistic men

autistic women are 3 times more likely to identify as homosexual than non-autistic women

ADHD & Sexuality

Research suggests that women with ADHD are more likely to have had homosexual experiences (Young & Cocallis, 2023)

However, generally, individuals with ADHD do not differ from neurotypical peers in their self-reported sexual orientation

BUT the potential to show more hypersexual behaviours (Hertz et al., 2023; Soldati et al., 2021

ADHD features and sexuality

impulsivity → risky sexual behaviour

dopamine → sensation seeking and reward seeking

inattention → distractibility and difficulty focussing

sensory sensitivities → discomfort and repelled

Gender: the basics

"sex" vs "gender"

"Sex" typically refers to biological attributes, such as chromosomes, hormones, and anatomy

"Gender" is largely understood as a social construct:

Involves the norms and expectations that societies create around what it means to be a "man," "woman," or other gender identities

These norms vary across cultures and change over time

Quick recap of PSY2004

Kohlberg's Stages:

Stage 1 (2-3 years): Gender Identity based on appearance.

Stage 2 (4-5 years): Gender Stability over time, still appearance-based.

Stage 3 (6-7 years): Gender Constancy across changes.

Nature vs Nurture

Biological Factors: Hormones (androgens) influence development. Intersex conditions and transgender/twin studies are relevant.

Social Cognitive Theory: Gender development involves personal, environmental, and behavioral factors.

Gender Similarity Hypothesis:

Genders are more alike than different in most variables

PSY1004: key terms

As children develop, they learn to perform behaviours associated with their gender.

Gender-typing and gender expression are the processes by which adopt observable behaviours in line with our construction of gender.

gender-typed preferences and behaviours result from the combined influence of biological, psychological and sociocultural processes (Leaper, 2013) i.e. biopsychosocial model

Gender identity

Gender is a complex interplay of social, cultural, and personal factors, distinct from the biological concept of sex

Gender identity is an individual’s sense of their own gender

it is a deeply personal experience that may or may not align with the sex they were assigned at birth

gender identity exists on a spectrum, and people may identify as male, female NB or other identities

gender diversity: experiencing of aspects of your gender as different from your assigned sex at birth

gender diversity can result in gender incongruency where a person’s gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth

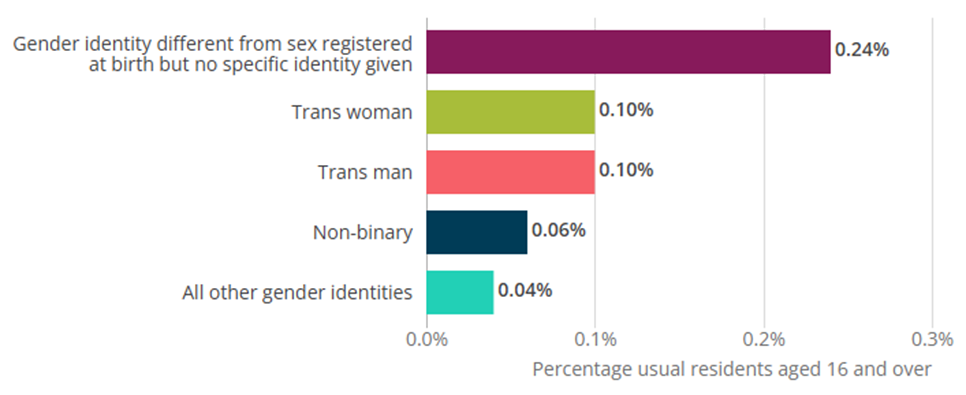

The general population

Survey-based research estimates that as many as 1% to 2% of adolescents identify as gender diverse (i.e. gender nonconforming or transgender; Rider et al., 2018)

In the 2021 UK Census 0.5% of the general population indicated that their gender identity differed to their sex registered at birth

Gender dysphoria

People may experience discomfort or distress when their assigned sex is different from the gender they identify with

This is known as gender dysphoria

In the UK, transgender people must be assessed for gender dysphoria before physical interventions such as gender affirming hormones and surgery can be accessed on the NHS

NB. Not all trans people have dysphoria

While many transgender individuals do experience gender dysphoria, it's not a universal experience, and some transgender individuals may not experience it at all. Cisgender people can also experience dysphoria.

DSM-5-TR: children

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least six of the following (one of which must be the first criterion):

A strong desire to be of the other gender or an insistence that one is the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

In boys (assigned gender), a strong preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong preference for wearing only typical masculine clothing and a strong resistance to the wearing of typical feminine clothing

A strong preference for cross-gender roles in make-believe play or fantasy play

A strong preference for the toys, games or activities stereotypically used or engaged in by the other gender

A strong preference for playmates of the other gender

In boys (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically masculine toys, games, and activities and a strong avoidance of rough-and-tumble play; or in girls (assigned gender), a strong rejection of typically feminine toys, games, and activities

A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy

A strong desire for the physical sex characteristics that match one’s experienced gender

DSM-5-TR: adolescents & Adults

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and their assigned gender, lasting at least 6 months, as manifested by at least two of the following:

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and primary and/or secondary sex characteristics (or in young adolescents, the anticipated secondary sex characteristics)

A strong desire to be rid of one’s primary and/or secondary sex characteristics because of a marked incongruence with one’s experienced/expressed gender (or in young adolescents, a desire to prevent the development of the anticipated secondary sex characteristics)

A strong desire for the primary and/or secondary sex characteristics of the other gender

A strong desire to be of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

A strong desire to be treated as the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

A strong conviction that one has the typical feelings and reactions of the other gender (or some alternative gender different from one’s assigned gender)

Gender Diversity in autism

the first systematic study was led by de Vries et al (2010): investigated the incidence of autism in children and adolescents referred for gender diversity services

7.8% of the sample met strict diagnostic criteria for autism - 10 x higher than the prevalence of autism in the general population at that time

Strang et al, (2018): identified studies of gender diverse and transgender youth that included only clinical autism diagnoses or autism diagnosed through comprehensive methods

in all 7 available studies rates of clinical diagnoses were significantly greater compared to the general population

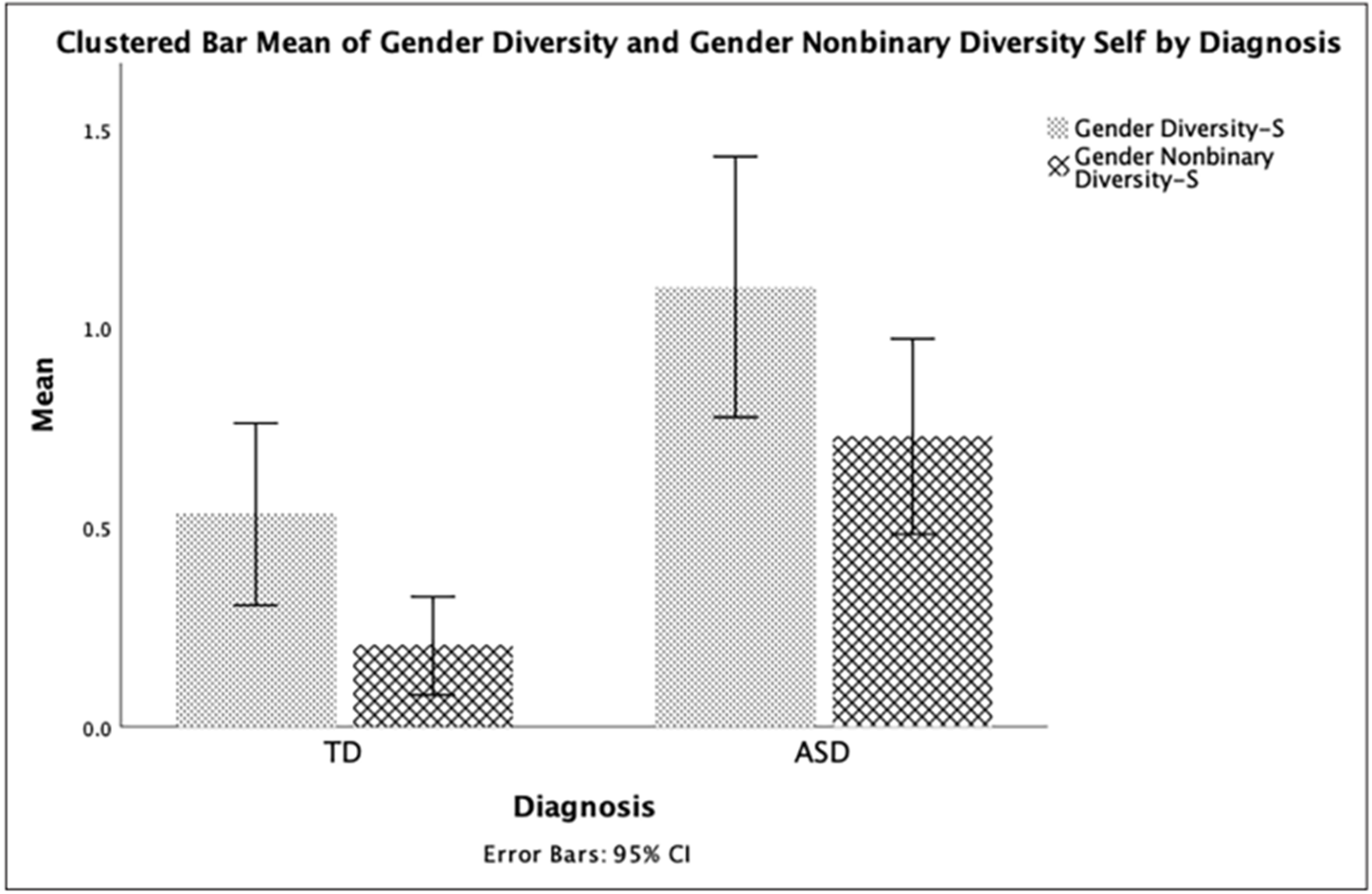

Corbet et al., 2023

gender diversity research with autistic children has typically relied on parent-report based on a single question

used the gender diversity screening questionnaire (self report and parent report)

two domains: binary Gender Diversity and NB Gender diversity

244 children (140 autism and 140 neurotypical)

self-report: autistic children showed higher gender diversity (both NB and binary) than neurotypical children

parent-report: a significant difference in gender diversity between the groups on body incongruence

underscores “the need to better understand and support the unique and complex needs of autistic children who experience gender diversity”

Gender diversity & ADHD

Very limited, few studies specifically look at ADHD

Warrier et al., 2020 – Transgender & Gender diverse individuals had elevated rates of ADHD

Prevalence rate of 8.3% in children and adolescents referred for gender care (Holt et al., 2016)

Prevalence rate of 4.3% in TGD adults (Cheung et al., 2018).

Ignatova et al., 2025:

10,277 ADHD & Transgender early adolescents (12-13 years)

Data taken from the longitudinal Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study (based in the US)

Methods: “Are you transgender?” Yes (TG), no (CG) or maybe (GQ)

Gender diverse individuals showed higher levels of ADHD traits

Results reduced when controlling for stress

Authors linked to current climate in the US

Lived experience: autistic and transgender- Cooper et al., 2022

21 autistic adults took part in semi-structured interviews

All participants identified as transgender and/or non-binary

Main Findings:

Distress due to their bodies not matching their gender identities, while managing complex intersecting needs

Societal acceptance of gender and neurodiversity

Barriers in accessing healthcare for their gender needs

Tension between need to undergo a physical gender transition versus a need for sameness and routine

Cooper et al., (2022): Positive experiences

“We see the world differently” (Participant 22), referring to the idea that being autistic allows one to step outside of societal norms and follow your own path

“I have never tried to fit in with people, or very rarely. So whilst now my gender presentation is very stereotypically male, there are some things that I do are intentionally more feminine, but I don't care” (Participant 12)

“Then after having a [autism] diagnosis a lot more of my experiences have come to light again and there's things that I do actually make me really uncomfortable or things that really don't suit me that I have edited to ignore a long time ago.” (Participant 17), found the diagnosis comforting and this allowed new coping strategies to be implemented

DSM-V-TR Autism

“Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment (e.g., apparent indifference to pain/temperature, adverse response to specific sounds or textures, excessive smelling or touching of objects, visual fascination with lights or movement)”

Dysphoria & Sensory sensitivities

Cooper et al., 2022:

Some participants described ‘sensory dysphoria’ - distress linked to sensory experiences

Wearing uncomfortable fabrics and shapes associated with girls’ clothes

Sensory challenges of puberty including periods, and growing facial hair

‘I was stuck between having really bad gender dysphoria not wearing a binder or feeling really uncomfortable sensory wise.’

Biological theories

Prenatal Hormone Exposure:

Variations in prenatal hormone exposure could contribute to differences in how individuals perceive and experience gender

not a simple cause-and-effect relationship

Brain Structure and Function:

Differences in structure and function could influence how individuals process and internalise social constructs like gender

Differences in brain regions involved in social cognition and self-perception might play a role

Increased self-identification

Autistic individuals may be less influenced by societal norms and expectations surrounding gender & sexuality

Leading to a greater likelihood of expressing their authentic gender or sexual identities, even if it deviates from societal norms

In other words, they may be less likely to suppress or conform to traditional gender roles or sexual identities due to social pressures

Differences in social cognition & sensory processing

Systemising and Pattern Recognition:

a more analytical approach to gender, breaking down its components and questioning traditional norms

Intense Focus and Special Interests:

Increased depth, leading to a more profound understanding of their own identity & less influence from outside sources

Sensory sensitivities/sensation seeking:

Certain clothing textures or social environments associated with specific genders might be intensely uncomfortable

Preference for certain gendered presentations due to the sensory input it provides

Sex education in Down Syndrome

Gender Identity, Sexuality & Down Syndrome

Limited to no studies investigating gender diversity in Down Syndrome

Parent-report regarding more general views of sexuality in DS

No studies directly speaking to individuals with DS

Instead, studies focus on the need for and improvement of sexual education for individuals with DS

Sexual education in DS

The World Health Organization advocates for SE as a human right

BUT adolescents and young adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities are frequently excluded

Often focuses on safety and abuse prevention rather than a holistic approach

healthy relationships, consent, and sexual fulfilment

Need to work with these individuals to develop implement more accessible and effective SE programs

Schmidt et al., 2021

Improving the accessibility of sexuality education (SE) for individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities.

Qualitative data collection through interviews and focus groups

Individuals, parents, healthcare providers, and educators.

Modalities

Educational guides

Visuals

Videos

Universal Design for Learning

Direct, explicit instructions

Additional:

Role-playing & modelling

Open communication

Importance of parental support and education

Settings:

one-to-one

small groups

combination

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

UDL adapts education to fit diverse learner needs

The 3 UDL Principles

Representation (the "what"): Offer information in varied formats (e.g., visual, auditory).

Action/Expression (the "how"): Provide different ways for learners to interact and express themselves.

Engagement (the "why"): Increase motivation through choice, relevance, and collaboration.

UDL in Sexuality Education

UDL makes SE accessible and engaging for all

Summary

Sexuality in autism and ADHD

Gender Identity in autism and ADHD

Increased gender diversity in autism

Little research, but suggestion of increased gender diversity in ADHD

Theories underlying increases in gender diversity/sexual identities

Biological

Self Identity

Differences in cognition & sensory processing

Sex education in Down Syndrome

Reading- cooper et al

Abstract

Autistic people are more likely to be transgender, which means having a gender identity different to one’s sex assigned at birth.

Some transgender people experience gender dysphoria.

In this study, 21 autistic adults were interviewed about their experience of incongruence between their gender identity and sex assigned at birth, and any associated distress.

The interviews were transcribed and analysed using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis.

Participants experienced distress due to living in a world which is not always accepting of gender- and neuro-diversity.

Participants described barriers in accessing healthcare for their gender needs.

Some participants felt being autistic had facilitated their understanding of their gender identity.

Other participants described challenges such as a tension between their need to undergo a physical gender transition versus a need for sameness and routine.

In conclusion, there can be both positive experiences and additional challenges for autistic transgender people.

Lay abstract

Warrier et al. (2020) found that that transgender adults were 3.03–6.36 times more likely to be autistic than cisgender people (i.e. people with congruence between their gender identity and sex assigned at birth).

Other research has explored the relationship between autism and transgender identities, ranging from case-studies of transgender autistic individuals, to measuring autism traits and diagnoses of Autism Spectrum Disorder in transgender people and individuals accessing gender clinics, and rates of transgender identities in autistic individuals across the lifespan.

This may not be unique to autism; systematic reviews and large-scale studies have indicated that ADHD may also be more common in transgender individuals compared to cisgender individuals

Gender dysphoria diagnoses:

Some transgender individuals experience gender dysphoria, which is defined in the DSM-5 as a significant incongruence between an individual’s gender identity and assigned gender leading to distress or impairment.

The ICD-11 diagnostic criteria have been amended to focus less on distress, broadening the criteria and labelling this as gender incongruence.

The criteria for gender incongruence involve a marked and persistent mismatch between an individual’s assigned sex and gender, frequently leading to a desire to transition gender. Nonetheless, in the United Kingdom, and in line with the Worldwide Professional Association for Transgender Health standards of care, an assessment of gender dysphoria must be made before physical interventions such as gender affirming hormones and surgery can be accessed, and so the experience of distress linked to this incongruence is key to accessing healthcare.

Therefore, in this study, we focus on experiences of dysphoria linked to gender incongruence.

Support for gender dysphoria:

In the UK, individuals can access NHS gender clinics for psychological support and physical treatments including hormone treatment and gender confirmation surgery.

A systematic review found evidence that in adults with gender dysphoria, undergoing physical interventions improves psychological well-being and quality of life, but concluded that higher quality evidence is needed.

Furthermore, the rates of autism of participants in these studies are not known, and so research investigating the well being of autistic people following physical gender transition is needed.

A recent systematic review and meta-synthesis indicated that a wider range of experiences than those in DSM-5 gender dysphoria criteria also contribute to distress in transgender adults.

These included being socially isolated due to being transgender, being misgendered, and cognitive and emotional processes linked to experiences of transphobia and harassment.

These experiences can be understood in the context of gender minority stress theory, which refers to experiences of stigma and discrimination due to being transgender which contribute to mental health difficulties.

Stress due to autistic identity

Given that autistic people also experience minority stress due to their autism identity, it is likely that the experiences of being autistic and being transgender intersect in clinically meaningful ways.

Mental health problems are more common in autistic people and in transgender individuals.

There is emerging evidence that being both transgender and autistic is associated with yet higher rates of mental health problems.

Autistic and transgender individuals

Strang et al. (2020) call for research focusing on the lived experience of gender identity in autistic people, and towards an understanding of the intersection of autism and transgender identities.

To date there have been two qualitative studies published on the lived experience of gender diversity and autism.

There have been a further two community-based participatory design papers describing the development of a clinical intervention for young autistic people who are transgender.

Coleman-Smith et al. (2020) investigated the lived experience of gender dysphoria in 10 autistic adults in the UK.

This study used Grounded Theory and found one overarching theme, named ‘conflict versus congruence’.

This theme described the participants’ experience of conflict between their gender identities and bodies, and also to inter- and intra-personal conflict which was linked to being autistic as well as transgender.

Some participants spoke of autism allowing the freedom of expression to embrace their gender identity while others saw autism as a barrier to accessing gender transition.

This is in line with research showing that autistic people experience barriers to accessing health care more broadly.

A qualitative study which used framework analysis with 22 transgender autistic youth in the US found that participants reported a strong need to live in their affirmed gender.

Participants emphasised that their gender identity would persist, and that they experienced significant gender dysphoria, but did not feel the need to conform to gender stereotypes.

Participants felt that being gender and neurodiverse brought challenges, and that their gender identity had been questioned due to their autism. These two important studies demonstrate that autism may affect the phenomenology of gender dysphoria and impact access to gender transition services. It is important to build on this research to provide an evidence base informing healthcare services provided to this group.

To achieve this, researchers need to develop a nuanced understanding of how the experiences of being autistic and experiencing gender dysphoria influence and interact with each other. In this study, we aimed to answer the question: what is the phenomenology of gender dysphoria in transgender autistic adults?

Method- methodological approach

IPA is a qualitative research method which focuses on a specific phenomenon, such as gender dysphoria, and aims to distil the essence of this experience.

IPA emphasises the individual lived experiences of participants, and focuses on how each participant understands and makes sense of their experiences of a particular phenomenon.

This approach acknowledges that the researcher will bring their own experiences and expertise to the analysis, and this must be reflected upon by keeping a reflexive attitude and maintaining a keen awareness of any researcher biases within the analytic process.

IPA has been identified as an important tool in autism research due to its focus on the lived experience and meaning to autistic individuals, and in this study, we aimed to stay close to the meaning-making of the individual in order to offer insights into participant experiences, while remaining aware of our identities as non-autistic researchers.

IPA achieves this through careful analysis of themes in each individual transcript, before moving on to develop themes in the next transcript.

This process continues until each individual set of themes has been collated, and then themes are developed across the data set.

participants

21 adults who had a clinical diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder.

We verified by viewing individual diagnostic reports confirming receipt of an autism diagnosis from a qualified health professional.

All participants identified as transgender and/or non-binary and had experienced distress in relation to the incongruence between their gender identity and sex assigned at birth, which they discussed with a health professional.

Participants therefore may or may not have met DSM-5 criteria for Gender Dysphoria.

This was to ensure that a range of autistic experiences of distress linked to gender incongruence were included.

The sample was relatively homogeneous, in that all participants had an autism diagnosis and experience of gender dysphoria.

A larger number of participants were invited to take part to ensure a range of gen der identities, ages, stages of transition and geographical location in participants, following advice from the patient and public involvement group who were all autistic transgender adults.

Participants were recruited from NHS adult autism services (n = 10), NHS gender clinics (n = 3) and through community groups (n = 8) including transgender and autism support groups.

Some of the community group sample invited other group members, (snowball sampling).

All participants who identified as male were AFAB, all participants who identified as female were AMAB and of those who identified as non-binary/genderqueer; five were AFAB and one was AMAB.

Of those with complete data, seven (44%) requested support for gender dysphoria and then received an autism diagnosis, and nine (56%) had an autism diagnosis before requesting support for gender dysphoria.

Procedure

In the NHS context, clinicians within each recruitment site spoke to potentially eligible participants about the research project during routine clinical appointments.

This clinician assessed participant eligibility for the study, including checking for a confirmed autism diagnosis and experiences of gender dysphoria, before gaining consent from the potential participant to give their contact details to the research team.

Participants who were recruited via other members of community groups made direct contact with the study team.

The research team assessed community group participants for their eligibility to participate, including confirmation of autism diagnosis by clinic letter from a qualified medical professional, before inviting eligible participants to take part.

Participants were invited to meet with a researcher either in-person or online to give fully informed consent.

After, participants completed a questionnaire collecting information about age, gender identity, current sexual orientation and journey through the health service for support around autism and gender dysphoria.

Next, participants were interviewed by the first author about their experience of distress linked to gender incongruence and of seeking help for this in the NHS.

Interviews took place Dec 2019- October 2020 and lasted around 66 min (range = 39–104 min).

The topic guide covered:

earliest experiences of gender dysphoria;

experience of being autistic and having gender dysphoria;

interaction of gender dysphoria, autism and mental health;

seeking help for gender dysphoria and autism adaptations in services.

open questions were used as much as possible.

However, some needed autism adaptations to fully respond to questions, including writing down responses (n = 3), having someone else in the room to support them (n = 1), and for all participants, the interviewer used a flexible interview style including closed prompt questions.

Some participants took more prompting and were less able to describe their feelings; however, this formed part of the analysis in itself.

Interviews were audio recorded using a digital recorder and the audio recording was sent to a professional transcription company and transcribed using an intelligent verbatim method.

Participants were reimbursed with a £25 shopping voucher and sent a debrief form following participation

Analysis

Analysis involved in-depth noting or coding of each individual transcript focused on capturing descriptive, linguistic and conceptual aspects of the data, followed by the development of themes capturing important aspects of the individual’s experience of gender dysphoria.

Themes were developed using processes of grouping together related themes, themes with oppositional relationships, those which shed light on contextual elements and themes which shared a similar function within the transcript.

Once transcripts were analysed, themes were developed for the whole data set using similar strategies.

Due to the large sample size for an IPA study, the number of participants for whom each theme was relevant was taken into account.

Where more than half of the participants (n ⩾ 10) had experienced a theme, it was categorised as recurrent and considered for the final analysis.

To ensure the credibility of the analysis, the authors discussed their positionality and prior assumptions about the topic before and throughout data collection.

The first author kept a reflexive diary during the research process, as well as attending an IPA peer supervision group with other IPA researchers.

The analysis was critically evaluated in the IPA group, in supervision and with the patient and public involvement group to ensure that the analysis was credible and grounded in the transcripts and participants’ reported experience

Community involvement

A group of transgender autistic adults (n = 6) were consulted and formed an involvement group for the research project.

These individuals were identified through an NHS run peer support group for autistic transgender adults, and could contribute by giving their opinions on the suggested research question and methods.

They also helped to ensure study materials were adapted for autistic adults, reviewing the information sheet and topic guide for the interview.

Finally, they reviewed the final analysis and theme names, and com mented on how the theme names and descriptions could be made accessible to the autistic community

results

In the last paragraph of the results, we present themes which were endorsed by fewer participants but which are relevant to the research question.

Making sense of distress and finding my identities

The first superordinate theme describes the discomfort and distress that all participants experienced, and had three sub themes. This discomfort was experienced in participants’ bodies and in their sense of self, linked to their multiple identities and life experiences.

Experiencing and describing body distress.

This subordinate theme referred to the distress participants felt having a body that did not match their gender identity

all participants described this to some extent, but many struggled to articulate it.

Participants spoke of a range of negative emotional responses to their bodies including depression, anxiety, anger and disgust, with some referencing dissociation from their bodies.

Participant 6 described this: I was resigned to the fact that I’m stuck being a girl . . . I felt fairly numb and empty, and really not connected with my body. And I used to feel physically awkward and always tense. I could never relax in my body and that in itself would bring discomfort.

A non-binary participant described experiencing ‘an estrangement’ from their body; I feel most comfortable and at my best with broader shoulders, and more body muscle . . . with an androgynous, strong shape to me. I go to some effort to hide if I want others to treat me a certain way, which is tedious, but I am more comfortable in my skin.

Some participants described puberty as being particularly distressing as their body developed in an unwanted way.

For example, a trans male participant: ‘I kind of almost grew up like a boy and then puberty happened and it was very distressing, like in my brain I wasn’t expecting it to happen’.

For many participants, these experiences of embodied distress were difficult to articulate verbally.

For example, participant 22 said ‘I may over-estimate or under-estimate’ gender dysphoria, and stated ‘It’s hard to explain. I find it hard identifying which emotion I’m feeling. Everything just feels like stress’.

Some participants used concrete, behavioural markers when describing their experience of gender-related distress: ‘. . . it’s quite unpleasant. There were situations where I was going to cause harm to my family’, while others described their gender dysphoria in more abstract terms: ‘I’m sort of nowhere. Sort of disappeared . . . I don’t know. It makes me feel sad’ (5), showing challenges in communicating this bodily experience.

Making sense of who I am.

This subordinate theme described the importance most participants placed on understanding their identities, and the sense of unease when they did not have this understanding.

This led to feelings of discomfort and frustration linked to the person’s broader sense of self, going beyond the bodily experiences of the first subordinate theme.

Most participants spent significant time trying to understand themselves.

This was centred on gender identity and autism identity:

‘I was only diagnosed as autistic two years ago and that made me really re-evaluate stuff because instead of being awkward and difficult and not making sense it was actually this makes sense’.

Participant 13 felt a pressure to find a gender label and wondered: Am I female? Am I another thing? . . . I felt I had to fully label myself and fully figure out why it was. It was like – it’s hard to explain, but it’s the lowest I’ve ever felt.

Some described experiencing feelings of discomfort that they needed an explanation for and realising they were transgender and autistic was important in gaining an understanding.

For example, participant 19 said ‘It’s been such a relief to accept that there is something different about me and do things in a way that works for me’.

These realisations were comforting and allowed new strategies to be implemented to alleviate distress, such as participant 17 who stopped masking after a diagnosis

While some described the utility of labels and diagnoses for understanding the self, a few used different labels before settling on a transgender identity: ‘Yeah I went through a phase, “Well, if I can’t be a boy, then I’ll just be a butch lesbian”.

Intersecting and competing needs.

This subordinate theme described the overlapping difficulties that participants experienced which sometimes required competing solutions.

These complex experiences of distress contributed to being uncomfortable in oneself.

Some participants described these multiple needs as amplifying dysphoria, such as participant 17: ‘I think how intensely I process it [dysphoria] is autism related’,

some felt they were entangled and could not be separated, while others conceptualised these struggles as separate to their gender dysphoria.

Many participants described multiple challenges that they faced which caused significant psychological distress. These included mental health needs, traumatic experiences and autism-specific difficulties such as being overwhelmed by sensory experiences, and this contributed to distress

Many described a clash between their autism and gender needs, causing additional distress. Some described ‘sensory dysphoria’; experiences of distress in their bodies linked to sensory experiences including wearing uncomfortable fabrics and shapes associated with girls’ clothes, and the sensory challenges of puberty including periods, such as dealing with the smell of blood, and growing facial hair.

Many reported finding change stressful, alongside a strong need to undertake a social and/or physical gender transition, and that this caused tension.

Some expressed a desire for their transition to be precise and predictable, such as participant 16 who wished for ‘nice little tick boxes’ for transition.

Some participants felt a need to be certain about their gender, and reaching a sense of certainty brought a sense of relief.

Concrete thinking linked to autism made it harder for some participants to understand their gender, such as a nonbinary participant 19 ‘I hate trying to be a girl but I have to try and force myself to be a man because there’s only two options’.

While the intersecting needs at times contributed to dis tress, others felt that autism helped with understanding their gender such as the idea that being autistic allows one to step outside of societal norms and follow one’s own path.

Mismatch between needs as an autistic trans person and society

The next superordinate theme had three sub-themes:

doing gender

struggle of being different

battle for support.

This theme centred on participant experiences of living in their bodies, gender identities and with their autism features within the social world not always accepting of differences.

Most had needs not easily met in society. It was important that their gender identity and autism identity was affirmed by others, and they were able to undergo a gender transition despite the barriers they experienced.

Gender as social behaviour.

The first subordinate theme centred on the participants’ experience of their gender in the social world.

Individuals experienced their gender identity through the eyes of others, which meant learning how others thought about gender, how their experience fit with these gender norms, and ensuring their individual gender expression would stop others from misgendering them.

Some felt that gender was one of many social expectations to not make sense to them, through being unaware of gender as a concept or being confused by it.

Participant 20 explained how they felt this linked to their autism identity: ‘Being autistic is like everybody else has got the rulebook and you didn’t, so you can understand why gender would come into it because it was in the rulebook you do not get’.

Others felt comfortable in their non-conformity: ‘I have never tried to fit in with people, or very rarely. So whilst now my gender presentation is very stereotypically male, there are some things that I do are intentionally more feminine, but I don’t care’.

Many stated their rejection of gender norms, while many also felt a pull towards stereotypical gender expression.

Participants described feeling oppressed by gender norms that do not apply to them, such as participant 22 ‘if other people force gender roles on me I’m not considering them as a person’.

Some felt affected by gender stereotypes linked to autism: ‘people who see me as female may not necessarily pick up on my autistic traits as much’, referring to the way in which autistic traits can be perceived as being stereotypically male.

Some described feeling negative emotions when misgendered: ‘It was traumatic. Really painful and frustrating that they weren’t seeing what I wanted’.

For some, it is difficult to know what others thought about their gender- ‘I’d get too aware of how other people were perceiving me, to the point where I’d almost lose myself because I’m imagining being in their perceptive so much’ (5).

Struggle of being different.

This described the challenges of autistic people living in a world which is cisnormative, the expectation that gender identity aligns with sex assigned at birth, and where the differences associated with autism and being transgender can be perceived negatively.

Participants struggled against this, sometimes experiencing a desire to fit in to mitigate these negative social experiences, which could be challenging given their differences in gender and social expression.

Many described periods of their lives where they were ostracised and socially isolated due to their identities.

Most described being bullied, othered and socially isolated.

Some described having difficulties in social situations both as a result of autism and their different gender expression.

Many described autism as being the main cause of social difficulties: ‘being autistic, people were too preoccupied to think about my gender so I never really faced any problems regarding that’.

Resulting from this, some referred to a sense of shame, such as participant 16: ‘You feel that you’re not very good at this, you’re kind of failing as a person that you just don’t fit anywhere and you just want to retreat’. Some participants spent significant time worrying about how they were perceived by others, while some said that they did not worry what others thought.

Some described attempts to conform to norms around gender and social behaviour

Battle for support.

This subordinate theme summarised the struggle by almost all participants to be acknowledged in their identities by people in positions of power, primarily professionals in health, education and social care settings.

This theme also refers to most participants’ desire to communicate about gender and to undergo a transition, but that features of autism could create barriers to this.

The positions of authority held by clinicians made their affirmation of the person’s identity (as both trans and autistic) hold meaning and power.

Participant 10 said ‘the first appointment was a complete disaster and I don’t think the doctor even believed me. After that I didn’t go back for a long time’, demonstrating the power of a clinician’s initial response to a request for support around gender dysphoria, and that the clinician’s affirmation was needed to continue to get support.

Sometimes, interactions at a gender clinic, or with mental health professionals, were described as a battle to get the support the individual wanted. Participant 6 described arriving at general practitioner (GP) and gender clinic appointments ‘armed’ with the necessary information to ensure they got a referral or the support they requested.

Many spoke of significant barriers to accessing a gender clinic due to their autism.

Where participants did access a gender clinic, they did not always feel that their autism was considered, and participant 3 felt she ‘had to appear as neurotypical as possible’ to gender clinicians.

Others felt that adaptations were made: ‘once I had a set clinician that I saw every time, it got a lot better’.

Many participants spoke about communication with professionals being challenging.

Participant 7 experienced helpful communication adaptations: ‘giving us, I wouldn’t say a prompt but did you feel like this, or did you feel this?’.

Participant 16 described difficulties with the uncertainty of processes around attending gender clinics: It was very difficult because there’s no set rules especially with transitioning there’s no kind of checklist . . . It would be far easier if there was nice little tick boxes and a list with a timescale.

Participant 2 struggled with the physical environment at the gender clinic: they had these awful, bright lights that buzz, and the clinician has their computer on so that’s humming away, and the clock’s ticking and the temperature’s always way too hot and it just . . . bombards you with all the sensory stuff.

Additional themes

Themes which were endorsed by less than half the participants, but were of relevance, included that five participants described their vulnerability to abuse by others, with two specifically linking this vulnerability to being both transgender and autistic.

For example, participant 1 described how before making any social transition, he thought of himself as a man, and did not consider that others would not see him that way, leaving him vulnerable to abuse:

‘this guy attacked me and I was in a very vulnerable place ‘cause I had no idea, I just saw myself as male’.

Two felt being autistic meant they spent more time researching gender identity, with participant 12 worrying that gender was a special interest, before concluding that it was not

Two non-binary participants felt that autism was a more central identity than gender: ‘I grew up autistic and that, actually, is the prevailing narrative of my life’.

Discussion

Autistic participants described their experience of distress due to:

their gender identities not matching their bodies and struggle to articulate this experience

a need to understand their identities more broadly

manage complex and intersecting needs.

For some , gender related distress was increased by being autistic, with some feeling autism increased the intensity of dysphoria, while others described how features of autism allowed more freedom of gender expression.

Participants faced difficulties in:

the social aspects of gender expression and societal norms around gender identity,

experienced distress when not treated as their gender by others

and due to being autistic and living in a world which is not always accepting of gender- and neuro-diversity.

and experienced barriers in accessing healthcare for their gender needs.

It may be that the social communication differences characteristic of autism, and higher rates of alexithymia, increased the likelihood that their experiences were misinterpreted by clinicians. This may have led to the negative consultations with healthcare professionals.

Many spent time and energy trying to understand their identities. Uncertainty about identity was often linked to gender, but also extended to sense of self more broadly, and there was a need to make sense of their identity as an autistic person.

For some, gender and autism identities were seen as essentialist, that is, a fixed internal trait to be discovered, whereas for others, these identities were seen as socially constructed, that is, malleable traits influenced by the social environment.

These findings suggest that some autistic people with gender dysphoria have longer and more complex journeys to understand their sense of self and identity, beyond gender identity alone.

The experience of distress due to a mismatch between assigned and affirmed gender was concurrent with a range of intersecting and competing needs. Participants interviewed faced a wide range of additional stressors. These include:

a conflict between autism and gender needs,

other mental health needs and contextual stressors

such as experiences of abuse and trauma,

which contributed to increased dis tress and discomfort in the self.

Some individuals said that experiencing multiple stressors served to exacerbate their gender dysphoria, while others saw these additional stressors as being separate to the intensity of their gender dysphoria.

The findings suggest that autistic people may be more likely to have complex and multiple sources of distress which can increase the intensity of their existing gender dysphoria.

We identified some aspects of gender dysphoria which interacted with autism. Autism was described as having a positive effect on the understanding of gender for some individuals, with being autistic facilitating awareness of gender identity. This is consistent with ideas of autistic people being resistant to social conditioning regarding gender and ‘gender defiance’ in autistic people.

There were also descriptions of increased challenges at the intersection of autism and transgender identity, such as distress due to competing needs for routine versus undergoing a gender transition.

Autistic people often have a preference for certainty, and some were distressed when they were uncertain about their identity. This fits with previous research which found confusion was a part of the experience of gender dysphoria in the general transgender population.

Finally, sensory sensitivities characteristic of autism contributed to increased gender dysphoria. The gender as social behaviour theme highlighted that gender was expressed and recognised by others as social behaviour and this could contribute to gender dysphoria for the autistic participants.

The social differences characteristic of autism affected some participants’ under standing of how other people interpreted their gender expression. For some participants, less intuitive understanding of social conventions led to not identifying with gender norms; this was freeing for some, while others felt frustration when others expected them to conform to gender stereotypes.

This fits with qualitative research with autistic women that found participants did not feel compelled to conform to gender norms.

The struggle of being different theme highlighted that many participants face minority stress due to not matching societal expectations because of both their autism and gender identities.

Participants experienced adversity due to these differences. This suggests that autistic transgender individuals can face more social adversity than non-autistic transgender people. Also feelings of shame about one’s identity was highlighted, likely linked to internalised stigma about their identities.

The final theme focused on the ways participants advocated for themselves and managed to access healthcare to meet their varied needs despite additional barriers. Many participants felt let down by health services. Participants wanted their autism and gender identities to be acknowledged by health providers, without these becoming barriers to autism, mental health or gender care.

Participants identified a range of autism adaptations which would improve their experience of healthcare. These ranged from differences in practicalities about organising appointments, changes to the clinic environment and changes in clinician communication.

These adaptations are similar to those recommended for psychological therapy with autistic people.

These are in line with recent findings that autistic transgender youth experience more executive functioning related barriers to accessing gender healthcare compared to non-autistic transgender young people

our findings suggest these difficulties are also experienced by autistic transgender adults.

Discussion- critical evaluation

A strength was the focus on the lived experience of a group of participants who are frequently marginalised due to their identities as autistic and transgender.

We were able to recruit a range of participants from healthcare and community settings, with a range of gender journeys and stages of physical gender transition.

We ensured that the analysis stayed close to the meaning of gender dysphoria to participants, emphasising their individual experiences.

We carefully sampled adults who had a clinical autism diagnosis but who had broader experiences of distress around gender; this was a strength as it is relevant to many healthcare settings following WPATH (2012) standards of care, including in the UK, where a diagnosis of gender dysphoria is needed to access gender affirmation interventions, but definitions of gender related diagnoses and services are rapidly changing.

A limitation was the larger sample size; while there are published IPA studies that include similar participant numbers, this meant that necessarily the analysis had to move on more quickly from the individual analysis of each case to analysing themes across all cases.

Future research should further investigate the inner experiences of transgender autistic people, with less focus on gender dysphoria, encapsulating a range of gender journeys and experiences, outside of diagnostic criteria.

Moreover, research with a focus on the development of a sense of gender identity and both gender conforming and non-conforming behaviours in autistic children and young people is needed to understand gender identity development more broadly in this population.

Clinicians working with this group should be aware of the differences in the autistic experience of gender dysphoria and make adaptations to their practice so that this group can access appropriate healthcare and support