Materials Science I

1/305

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Hell on earth.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

306 Terms

The evolution of engineering materials

Engineering materials evolved from naturally occurring materials such as stone, wood, and clay to metals, polymers, ceramics, composites, electronic materials, biomaterials, and nanomaterials as human needs, technology, and processing methods advanced.

Why new classes of materials were developed

New materials were developed to meet increasing demands for higher strength, lower weight, better thermal and electrical performance, corrosion resistance, durability, and functionality.

Key stages in the evolution of materials

Stone Age (natural materials), Bronze and Iron Ages (metals), Industrial Age (steels and alloys), Polymer Age (synthetic polymers), and Modern Age (composites, semiconductors, biomaterials, nanomaterials).

Material properties

Material properties describe how a material responds to mechanical, thermal, electrical, magnetic, optical, and chemical influences.

Design-limiting properties

Design-limiting properties are material properties that must meet minimum required values for a component to function safely and effectively.

Examples of design-limiting properties

Stiffness, strength, toughness, electrical resistivity, thermal conductivity, and optical quality.

Why design-limiting properties are important

If any design-limiting property is inadequate, the component will fail regardless of how good other properties are.

Mechanical properties

Mechanical properties describe a material’s response to applied forces or loads.

Key mechanical properties

Stiffness, strength, hardness, ductility, toughness, and resistance to fracture.

Why mechanical properties matter in design

They determine whether a material can support loads, deform safely, and resist failure during service.

Thermal properties

Thermal properties describe how materials respond to temperature changes and heat flow.

Thermal conductivity

Thermal conductivity is the ability of a material to conduct heat.

Thermal diffusivity

Thermal diffusivity measures how quickly heat spreads through a material and is proportional to thermal conductivity divided by heat capacity.

Importance of thermal diffusivity

It determines how fast a material heats up or cools down for a given thickness.

Electrical conductivity

Electrical conductivity describes how easily electric current flows through a material.

Electrical resistivity

Electrical resistivity is the inverse of electrical conductivity and measures resistance to current flow.

Magnetic properties

Magnetic properties describe how materials respond to magnetic fields.

Hard magnetic materials

Hard magnetic materials retain magnetization and are used as permanent magnets.

Soft magnetic materials

Soft magnetic materials are easily magnetized and demagnetized and are used in transformers and electric motors.

Chemical properties

Chemical properties describe a material’s resistance to chemical attack and corrosion.

Common aggressive environments

Water, salt water, acids, alkalis, organic solvents, oxidizing flames, and ultraviolet radiation.

Optical properties

Optical properties describe how materials interact with light through reflection, refraction, absorption, or transmission.

Examples of optical behavior

Opaque materials reflect light, transparent materials refract light, and some materials selectively absorb wavelengths.

Density

Density is the mass per unit volume of a material.

Density trends among materials

Metals generally have high densities, polymers have low densities, and ceramics have intermediate densities.

Why density matters

Density affects weight, structural efficiency, and suitability for lightweight or load-bearing applications.

Stiffness

Stiffness is the resistance of a material to elastic deformation and is measured by the elastic modulus.

Stiffness comparison

Ceramics and metals are generally stiffer than polymers.

Why stiffness is important

High stiffness is required when dimensional stability under load is critical.

Strength

Strength is the ability of a material to withstand applied stress without failure.

Strength comparison

Metals and ceramics generally have higher strengths than polymers.

Role of temperature

Strength values are usually specified at room temperature unless otherwise stated.

Resistance to fracture

Resistance to fracture describes a material’s ability to resist crack initiation and propagation.

Brittle vs ductile behavior

Ceramics are typically brittle with low fracture resistance, while metals are more ductile with higher fracture resistance.

Importance of temperature resistance to fracture in design

Low fracture resistance can lead to sudden and catastrophic failure.

Conductivity comparison

Metals have high electrical conductivity, polymers and ceramics usually have very low conductivity, and semiconductors have intermediate conductivity.

Importance of electrical conductivity

Electrical conductivity is a design-limiting property in electrical and electronic applications.

Metallic materials

Metallic materials are characterized by metallic bonding, high electrical and thermal conductivity, and good ductility.

Typical properties of metals

High strength, good toughness, high density, and good formability.

Examples of metallic materials

Steel, aluminum, copper, titanium, and their alloys.

Polymeric materials

Polymeric materials are composed of long-chain molecules made of repeating units called mers.

Typical properties of polymers

Low density, low stiffness and strength, good corrosion resistance, and low thermal and electrical conductivity.

Examples of polymers

Polyethylene, polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride, polystyrene, and nylon.

Ceramic materials

Ceramics are inorganic, non-metallic materials composed of metallic and non-metallic elements.

Mechanical behavior of ceramics

Ceramics are stiff and hard, strong in compression, weak in tension, and brittle.

Other properties of ceramics

Low electrical and thermal conductivity, high temperature resistance, and good chemical stability.

Examples of ceramic materials

Glass, porcelain, bricks, concrete, alumina, and silicon carbide.

Composite materials

Composites are materials composed of two or more distinct phases combined to achieve superior properties.

Matrix and reinforcement

One phase acts as a matrix and the other as a reinforcing phase.

Types of composites

Metal-matrix, ceramic-matrix, and polymer-matrix composites.

Purpose of composites

To combine the best properties of different materials and achieve synergistic effects.

Electronic materials

Electronic materials are materials used for their electrical or electronic functionality, especially semiconducting behavior.

Key electronic materials

Silicon, germanium, gallium arsenide.

Examples of use of electronic materials

Integrated circuits, optical fibers, interconnects, and dielectric layers.

Biomaterials

Biomaterials are natural or synthetic materials designed to interact with biological systems.

Key requirement of biomaterials

Biocompatibility, meaning they do not cause adverse reactions in the human body.

Examples of biomaterials

Metals, ceramics, polymers, and composites used in implants, prostheses, and medical devices.

Nanomaterials

Nanomaterials are materials that have at least one structural dimension in the nanoscale range (1

Classification of materials by dimensionality

0D (nanoparticles), 1D (nanowires, nanotubes), 2D (nanofilms, nanocoatings), and 3D (bulk nanostructured materials).

Why nanomaterials are special

They often exhibit unique mechanical, electrical, optical, and chemical properties due to their small size.

Internal structure of materials

The internal structure refers to the arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules within a material.

Levels of structure

Atomic structure, crystal structure, microstructure, and macrostructure.

Why internal structure matters

Internal structure determines material properties and performance.

Atomic structure

Atomic structure describes the organization of protons and neutrons in the nucleus and electrons surrounding the nucleus.

Key atomic particles

Protons (positive), neutrons (neutral), and electrons (negative).

Importance of atomic structure

It determines chemical behavior and bonding characteristics.

Electrons in atoms

Electrons are negatively charged particles that occupy discrete energy levels or shells around the nucleus.

Role of electrons

Electrons determine chemical properties and bonding behavior of atoms.

Energy levels and shells

Electrons occupy shells labeled K, L, M, N…, corresponding to increasing energy and distance from the nucleus.

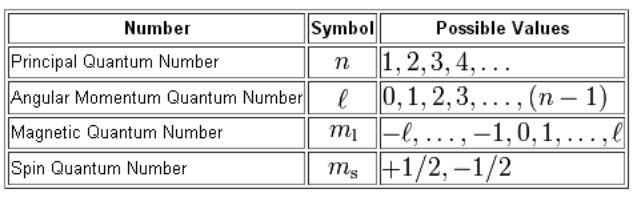

Quantum numbers

Quantum numbers describe the unique quantum state of an electron in an atom.

The four quantum numbers

Principal (n), azimuthal (l), magnetic (ml), and spin (ms).

Meaning of each quantum number

n (principal) defines the energy level or shell,

l (azimuthal) defines the subshell or orbital shape (s, p, d, f),

m_l (magnetic) defines the orientation of the orbital,

m_s (spin) defines the electron’s spin direction (+½ or −½).

Electron configuration

Electron configuration shows the arrangement of electrons in an atom’s shells and orbitals.

Rules for electron configuration

Aufbau principle (fill lowest energy orbitals first), Pauli exclusion principle (no two electrons have the same set of quantum numbers), Hund’s rule (maximize unpaired electrons in degenerate orbitals).

Periodic table

A tabular arrangement of elements ordered by atomic number, showing recurring (“periodic”) chemical properties.

Groups and periods

Groups (columns) share similar chemical behavior, periods (rows) represent increasing principal energy levels.

Why the periodic table is important

It allows prediction of element properties, reactivity, and trends such as atomic radius, ionization energy, and electronegativity.

Atomic bonding

Atomic bonding is the interaction that holds atoms together in a material.

Types of bonding

Ionic, covalent, metallic, and van der Waals (secondary) bonding.

Effect of bonding on material properties

Bond type determines mechanical, thermal, electrical, and chemical properties of solids.

Bonding forces

Forces that hold atoms together include electrostatic attraction (ionic), shared electron pairs (covalent), delocalized electrons (metallic), and weak dipole interactions (van der Waals).

Bonding energy

Energy required to break a bond; higher bonding energy usually results in higher melting and boiling points.

Primary bonds

Strong bonds that involve the transfer or sharing of electrons.

Types of interatomic bonds

Ionic bonds: electron transfer between atoms (e.g., NaCl),

Covalent bonds: electron sharing between atoms (e.g., diamond),

Metallic bonds: delocalized electrons shared across many atoms (e.g., copper).

Ionic bonding

Occurs between atoms with large differences in electronegativity (metal + nonmetal).

Covalent bonding

Occurs between atoms with similar electronegativities (usually nonmetals).

Bonding character

Most bonds are not purely ionic or covalent but have a degree of both.

Metallic bonding

Characterized by delocalized electrons moving freely among positive ion cores.

Properties of metallic bonding

High electrical and thermal conductivity, ductility, malleability, and shiny appearance.

Secondary bonding

Weak attractive forces between atoms or molecules that are not due to the sharing or transfer of electrons, unlike primary (ionic, covalent, metallic) bonds.

Types of secondary bonding

London dispersion forces (temporary dipoles), dipole-dipole interactions, and hydrogen bonding.

Effect of secondary bonding

Secondary bonds are weaker than primary bonds and influence properties such as melting point, boiling point, and solubility.

Quantum mechanics

Describes the behavior of electrons in atoms using wave functions.

Atomic orbitals

Regions of space where electrons are most likely to be found. Atomic orbitals explain the distribution of electrons, chemical bonding, and material properties.

Orbitals

Regions of space around an atom’s nucleus where there is a high probability of finding an electron. Defined by quantum numbers (n, l, ml, ms).

Shapes of orbitals

s: spherical,

p: dumbbell-shaped,

d and f: more complex shapes.

Each orbital can hold a maximum of two electrons with opposite spins.

Contour representation

Uses lines or surfaces to represent regions of constant electron probability. Visualizes orbital shapes and electron density distributions in space.

p orbitals

Three degenerate orbitals (px, py, pz) oriented along x, y, z axes. Dumbbell-shaped, each holds two electrons, important in covalent bonding.

d orbitals

Five orbitals with complex cloverleaf shapes, important in transition metals.

f orbitals

Seven orbitals with highly complex shapes, significant in lanthanides and actinides.