L7: Prosocial Behaviour

1/101

Earn XP

Description and Tags

Describe prosocial behaviour and critically evaluate social, evolutionary and biological perspectives on why we behave prosocially Explain and appraise the bystander effect and models of bystander behaviour: the bystander calculus model and Latané and Darley’s Cognitive Model Define and illustrate perceiver and recipient centred determinants of helping Describe the potential effects of receiving help

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

102 Terms

prosocial behaviour

accts that are positively viewed by society

Wispe, 1972: prosocial behaviour, consequences

positive social consequences

contributes to physical/psychological wellbeing of another

Eisenberg et al., 1996: what is prosocial behaviour

voluntary

intended to benefit others

types of prosocial behaviour

altruistic

helpful

helping behaviour

acts that intentionally benefit some else/group

altruism

acts that benefit another person rather than one’s self; performed w/o expectation of one’s own gain

difference between altruism and helping behaviour

helping- expect to receive smth in return for help given

altruism- do not expect to receive anything in return

what shld true altruism be?

selfless

issue w altruism

shld be selfless

difficult to prove selflessness

sometimes private rewards associated with acting prosocially e.g. feeling good

what marked the beginning of prosocial behaviour research

the murder of Kitty Genovese

The Kitty Genovese Murder

kitty was home when attacked

kitty tried to fight off her attacker and screamed and shouted for help

37 ppl openly admitted to hearing her screaming but failed to act

two perspectives on why and when people help

biological & evolutionary

social psychological

biological & evolutionary perspectives on why and when ppl help

mutualism

kin selection

social psychologicsl perspectives on why and when ppl help

social norms

social learning

biological & evolutionary perspective

• humans have an innate tendency to help others to pass our genes to the next generation

• helping kin improves their survival rates

• prosocial behaviour as a trait that potentially has evolutionary survival value

• animals also engage in prosocial behaviour

mutualism

prosocial behaviour benefits the co-operator as well as others; a defector will do worse than a co-operator

kin selection

prosocial behaviour is biased towards blood relatives because it helps their own genes

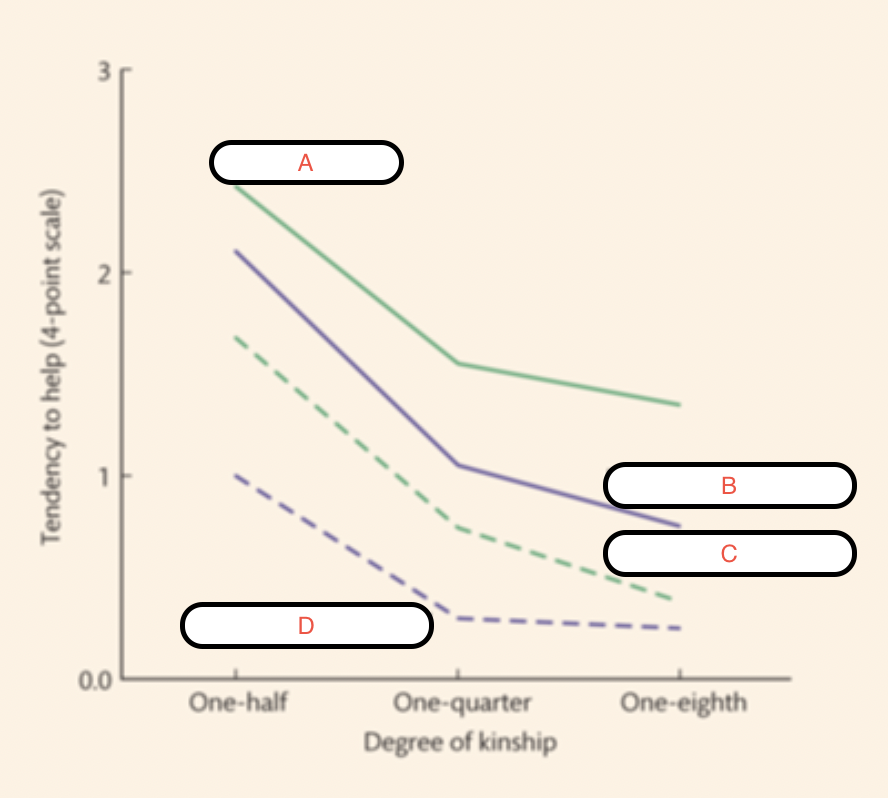

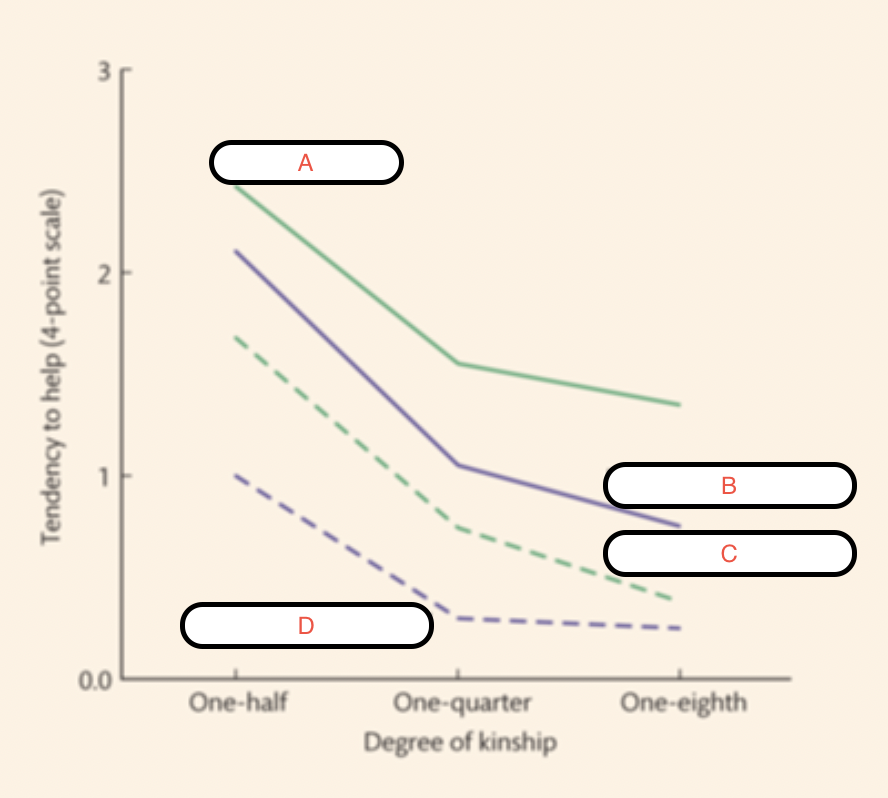

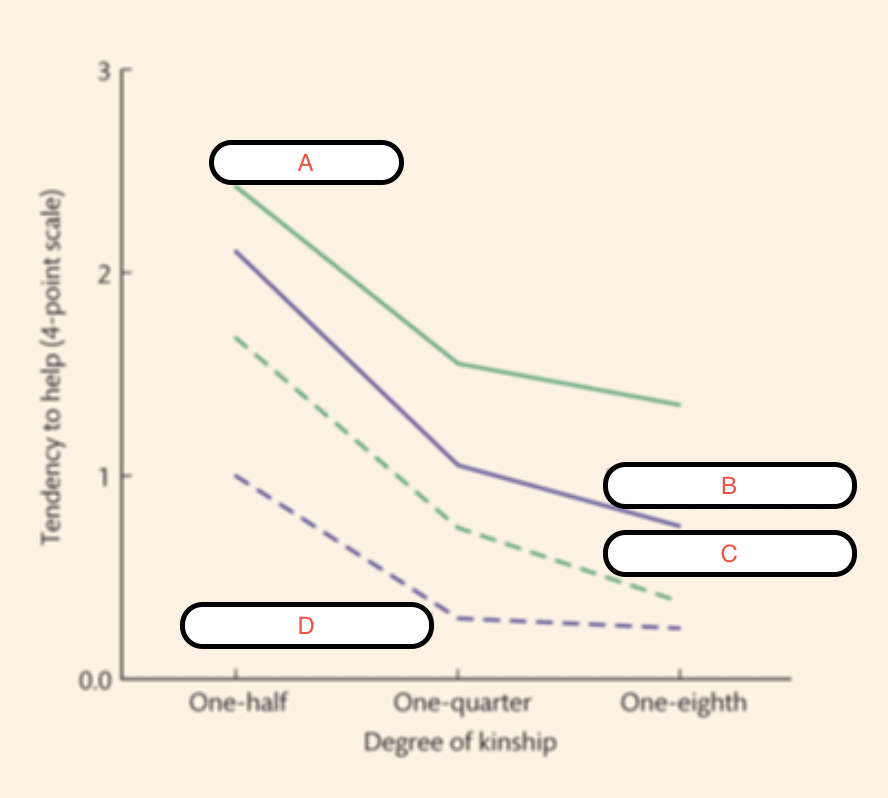

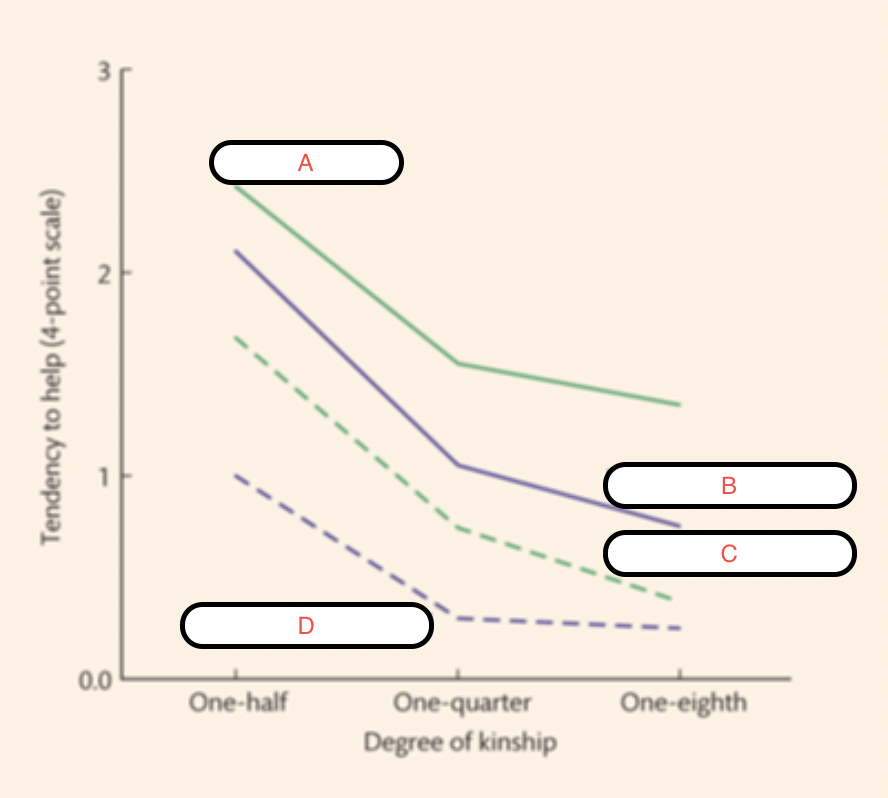

kin selection study procedure/measures

asked to rank how likely to help on a four point scale

degree of kinship measured

healthy or sick

everyday or life or death

kin selection: relatedness measure

degree of kinship, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8

kin selection study: asked how likely to help depending on…

degree of kinship

the person is healthy or sick

the situation is everyday or life or death

helping likeliness order for each condition (sick/healthy, everyday/life or death). in order of most to least likely to help.

sick x everyday

health x life or death

sick x life or death

healthy x everyday

kinship and helping likeliness in each condition (sick/healthy, everyday/ life or death)

closer kinship → more related → more likely to help

same in all conditions

label A

sick/ everyday

label B

healthy/ life or death

label C

sick/ life or death

label D

healthy / everyday

explain kin selection results in terms of evolutionary theory

consistent with it

closer to u → more likely to help bc improve success of genetic line

everyday → more likely to help the sick bc healthy can fend for themselves

life or death → more likely to help healthy bc they have better chance of survival and reproductive success → improve success of continuing genetic line

limitations of the biological and evolutionary perspective

does not explain why help non-relatives, like friends or even strangers

little empirical evidence- cannot assess evolutionary processes in lab, can’t manipulate how related etc, so all based on anecdotes/observation

does not explain why wld help in some circumstances but not others- e.g. familial violence, abuse

social learning theories ignored. Alternative accounts propose prosocial behaviour is learned, not innate (Eisenberg)

Lay et al., 2020: social psychological accounts

social guidelines that establish what most people do in a certain context and what is socially acceptable

what do social norms do

play a key role in developing and sustaining prosocial behaviour (e.g. not littering); these are learned rather than innate

how are norms enforced

conforming → social acceptance → rewarded

violate → social rejection → punished

how many social norms explain why people engage in prosocial behaviour

3

three social norms that may explain why people engage in prosocial behaviour

reciprocity principle

social responsibility

just-world hypothesis

reciprocity principle

Gouldner, 1960

we should help people who help us

if sm1 helps us, we feel we need to return favour and help them if they need

social responsibility norm

Berkowitz, 1972

we should help those in need independent of their ability to help us

just-world hypothesis

Lerner and Miller, 1978

world is just and fair place

if come across anyone undeservedly suffering we help them to restore our belief in a just world

Zahn- Waxler et al., 1992

childhood is a critical period during which we learn prosocial behaviour

how do children learn prosocial behaviour

giving instructions

using reinforcement- rewarding behaviour

exposure to models

giving instructions (Grusec et al., 1978): children learning prosocial behaviour

telling children to be helpful works

telling children what is appropriate establishes an expectation and guide for later life

tho if a child is told to be good but preacher is inconsistent then is pointless

how we respond to distress in others is…

related to how we learn to share, and how we learn to provide comfort etc

reinforcement: children learning prosocial behaviour

when young children are rewarded → more likely to help again

if not rewarded or are punished → less likely to offer help

Rushton and Teachman (1978) study

Rushton and Teachman (1978)

reinforcement and rewarding for learning to be helpful

children aged 8-11 observed adult playing game

adult seen to donate tokens won in the game to a worse off child

conditions of positive reinforcement, no consequences and punishment

vicarious reinforcement

children donated higher tokens when positive than no or punish

effect seen immediately and 2 weeks later

exposure to models: children learning prosocial behaviour

Rushton (1976)

concluded from review modelling is more effective in shaping behaviour than reinforcement

Gentile et al., (2009) study

what did Rushton (1976) conclude

modelling more effective in shaping behaviour than reinforcement

Gentile et al., 2009: study

children aged 9-14 assigned to play prosocial, neutral, or violent video games

playing video games w prosocial content increased short term helping behaviour and decreased hurtful behaviour in puzzle game

SLT

bandura 1973

if a person observes a person and models behaviour, not just mechanical imitation

it is knowledge of what happens to model that determines whether observer will help or not

Hornstein (1970): what was study investigating

SLT of prosocial/helping behaviour

Hornstein (1970)

conducted experiment where people observed model returning lost wallet

model appeared either pleased to be able to help, displeased at helping, or no strong reaction

later p came across lost wallet

those who observed pleasant condition helped most, those who observed negative helped least

modelling is not just imitation

observing outcomes → learning thru vicarious experience

bystander effect

apathy

people less likely to help in an emergency when they are with others than when they are alone

study on bystander effect

Latane and Darley 1968

Latane and Datane, 1968: bystander effect: procedure

emergency situations whilst completing questionnaire

- presence of smoke in the room

- or another p suffering a medical emergency

presence of others: confederates who do not intervene, other naiive ps, or alone

Latane and Datane, 1968: bystander effect: findings

very few intervened in presence of others

esp when others did not intervene

what did Latane and Darley’s study lead them to do

develop cognitive model, explaining deciding whether or not to help

Latane and Darley’s cognitive model

deciding whether or not to help

attend to what is happening + define event as emergency + assume responsibility + decide what can be done = give help

Latane and Darley’s cognitive model: steps

attend to what is happening- notice event and register that help may be required

define event as emergency- more likely to define if ppl beenn hurt, r in serious condition, or condition quickly deteriorating

assume responsibility- do we accept personal responsibility, may depend on how competent/ confident feel, may worry make things worse and so less likely to help

decide what can be done- do we call 999, intervene, actively help etc if safe to do so. if end up deciding nothing can be done, less likely to help

once all, in order, been fulfilled → help

various processes in these steps can lead to bystander effect

processes contributing to bystander effect

diffusion of responsibility

audience inhibition

social influence

diffusion of responsibility

tendency of an individual to assume that others will take responsibility

if everyone thinks someone else will help, then noone does

audience inhibition

other onlookers may make individual feel self-conscious about taking action

people do not want to appear foolish by overreacting

social influence (bystander effect)

other people provide a model for action

if they are unworried, the situation may seem less serious

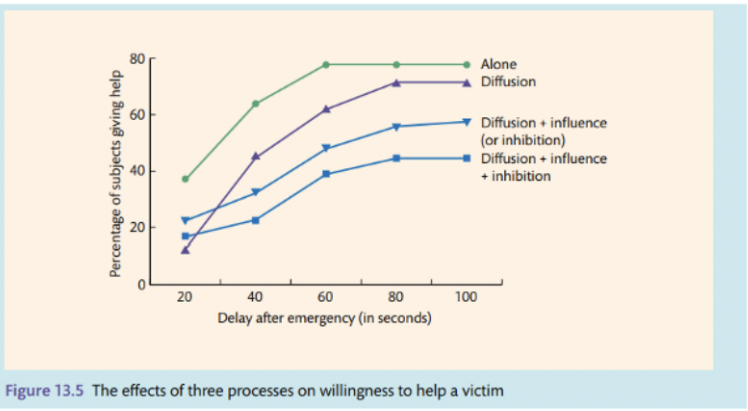

testing the processes underlying bystander apathy effect- study

Latane and Darley, 1976

Latane and Darley 1976: conditions

testing processes underlying bystander apathy effect

five conditions:

control: alone, cannot be seen by or see others

diffusion of responsibility: aware of another p but cannot see them

diffusion of responsibility + social influence: aware of another p, can see the p in monitor, cannot be seen themselves

diffusion of responsibility + audience inhibition: aware of another p but cannot see them, but can be seen themselves

diffusion of responsibility + social influence + audience inhibition: aware of other p, can see other p, aware other p can see them

Latane and Darley 1976: findings

help most when alone, control

help most when alone and most at 60s then plateu

less likely to help the more processes are at play

bystander calculus model

Piliavin et al., 1981

physiological processes- empathetic response

labelling the arousal- cognitive processes

evaluating consequences of helping

bystander calculus model: stage 1

physiological processes

in order to help, must have empathetic response to someone in distress/needing help

emotional arousal

greater arousal → more likely to help (Gaertner & Dovidio, 1977)

emphatic concern is triggered when we believe we are similiar to victim and can relate to them, we are more likely to help person (Batson & Coke, 1981)

three stages of bystander calculus model

physiological processes; 2. labelling the arousal; 3. evaluating the consequences of helping

bystander calculus model: stage 2

labelling the arousal

label this arousal as an emotion (e.g. distress, anger, fear)

personal distress at seeing someone else suffer- helping behaviour motivated by desire to reduce own negative emotional experience

involves cognitive processes

label arousal as emotion → reduce own negative emotional experience by helping

bystander calculus model: stage 3

evaluating consequences of helping

cost benefit analysis

costs of helping:

time and effort (Darley and Batson, 1973)

personal risk

costs of not helping:

empathy costs → not helping can cause distress to a bystander who empathises with the victim

personal costs of not helping victim can cause distress (e.g. feeling guilt or blame)

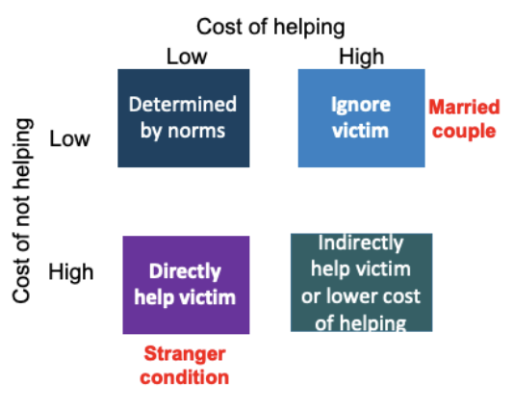

used to create cost benefit matrix of helping behaviour in an emergency

low cost of helping + high cost of not helping = most likely ot help directly

high cost of helping + low cost of not helping = most likely to ignore victim

Pilavin’s cost-benefit matrix of helping behaviour in an emergency

cost of helping = COH

cost of not helping = CONH

low CONH + low COH = determined by norms

low CONH + high COH = ignore victim

high CONH + low COH = directly help victim

high CONH + high COH = indirectly help victim or lower cost of helping

evidence for bystander calculus model

Shotland and Straw, 1976

Shotland & Straw (1976): procedure experiment 1

Ps witness a man and a woman fighting

condition: married couple vs strangers

measured intervention rate

Shotland & Straw (1976): findings experiment 1

65% intervention rate in strangers condiiton

19% in married couples condition

Shotland & Straw (1976): explain findings experiment 1

may be/feel higher costs of helping married couple bc may not want to impose in argument, couple may not want help

cost of not helping feels lower bc married and know each other so cld just be regular argument

stranger condition- cost of not helping feels a lot higher

if they know the strangers and do not help, may feel guilty

more likely to intervene therefore

contradicting bystander effect: study

recent Philpot et al., 2020 study

CCTV recordings

myth- when people observe ppl in need of help, have tendency not to help. research shows not the case.

90% of situations, 3-4 ppl intervened

Philpot et al., (2020): contradicting the bystander effect: study

CCTV recordings of 219 street disputes in three cities in diff countries- Lancaster, England; Amsterdam, Netherlands; Cape Town, SA

at least one bystander intervened in 90%

contrary to previous research, presence of others increased likelihood of helping- opposite of bystander effect

first large scale test of bystander effect in real life situations

in Capetown SA → violence, high risk of intervention

yet similar findings across all three locations, suggests universal phenomenon

Genovese’s murder

admittance that the story was exaggerated by media

reporting flawed and grossly exaggerated number of witnesses and what they had percieved

limitations of Philpot et al., 2020 study (comprehensive)

CCTV- if ppl know it is an area w cctv then might be more likely to help bc lower risk as being recorded

Areas w cctv are likely policed/ monitored more so again, potentially lower risk

Ethical issues- using ppl without their permission

CCTV- no audio, cannot tell relationship between ppl

CCTV- miss if ppl r texting/calling police etc

Do not know if variables in common informing why ppl help

Cannot see if ppl r discussing whether or not to help and then deciding too

Cannot see how many ppl in area

Likely areas that are well lit/ central- again, more supervision, ppl less likely to do super dangerous things

Contexts missed- helping ppl in non-conflict situations, e.g. medical emergencies, crossing roads, etc

Not done non-western cultures

Ps may know being observed by CCTV and therefore intervene

Contexts- demographic, P information, police trust in area, etc

Only 219 footage across 3 cities in diff countries, need larger data

Contexts- only cities. Cities often policed, street lights etc. what abt rural areas? Safety of diff city areas?

Public areas where social desirability/ compliance present as in public → what abt in less public areas or when cannot see who else is intervening?

Ambiguity?

Philpot 2020 study: strengths (comprehensive)

Real, external validity, very high ecological validity

Large amount of data in comparison to lab amounts

Harder to manipulate

Real life situations, video evidence, objective

Less demand characteristics, social desirability bias- do not know being observed for this study (although may know being observed)

Different countries

Philpot 2020 study: strengths

large scale test of bystander effect using real life scenarios- high ecological validity

effect consistent across three diff countries- one with slight diff context (Capetown)

Philpot 2020 study: limitations

only cities, mostly western

interventions defined broadly so cld capture range of diff things

lack of audio

perceiver centred determinants of helping

personality

mood

competence

recipient centred determinants of prosocial behaviour

group membership

responsibility for misfortune

personality

perceiver centred determinant of helping

is there such thing as an altruistic personality?

Bierhoff, Klein & Kramp, 1991

Bierhoff, Klein & Kramp, 1991: personality

ppl who helped in traffic accident vs those who did not help

helpers and non helpers distinguished on: (helpers scored higher on):

norm of social responsibility

internal locus of control

greater dispositional empathy

evidence correlational and not clear whether personality traits cause helping behaviour

mood

perceiver centred determinant of helping

individuals who feel good → more likely to help someone in need

Holloway et al., 1977: receiving good news → increased willingness to help

Isen (1970): teachers who were more successful on task → more likely to contribute later to fundraising event

those who did well donated 7x more than others

mood effects may be short lived

Isen, Clark, Schwartz 1976: increased willingness to help stranger only within first 7mins of positive mood induction

may be re how good positive mood induction technique is

moods change quickly and instantly

may only engage in helping behaviour for as long as moods are good

feeling competent

perceiver centred determinant of helping

feeling competent to deal with emergency → more likely that help will be given

shld take feeling competent into consideration, esp when looking at cognitive model and step of assuming responsibility

feel competent → more likely to assume responsibility → more likely to help

awareness that ‘i know what i am doing’ (Korte, 1971)

specific kinds of competence have increased helping in diff contexts

certain skills perceived as relevant to some emergencies (Shotland and Heinhold, 1985)

Midlarsky & Midlarsky, 1976: competence + helping

people more willing to help others move electrically charged objects if they were told they had a high tolerance for electric shocks

Schwartz & David: 1985

people more likely to help recapture dangerous lab rat if they were told they were good at handling rats

group membership

receiver centred determinant of prosocial behaviour

social identity theory applied to helping behaviour

same or similar social group to us → more likely to help

studies by Levine

Levine et al., 2005: study 1

group membership and prosocial behaviour

45 man u fans

ps directed to take short walk, witness emergency incident

group membership manipulated

confederate wears man u, liverpool fc, or plain sports top

rate of helping confed measured

man u fans more likely to help man u fans than liverpool or non supporter

helping behaviour increased for in group members

Levine et al., 2005: study 2

group membership and prosocial behaviour

same design as study 1

ps told taking part in study abt football fans

focusing on positives of being football fan

measured helping behaviour to confed wearing man u, liverpool fc, or plain top

equally likely to help confed wearing man u or liverpool fc top

those wearing plain top less likely to be helped

broadening boundaries of social categories may increase helping behaviour

responsibility for misfortune

recipient centred determinant of prosocial behaviour

ppl generally more likely to help ppl who are not responsible for their misfortune (e.g.- just-world hypothesis_

Turner DePalma et al., 1999: procedure

responsibility for misfortune

98 Ps read booklet abt fictional disease

disease either cause by genetic anomality or action of individual or no information given

measured Ps belief in just world

offered 12 helping options with differing commitment levels

Turner DePalma et al., 1999: findings

responsibility for misfortune

helping behaviour significantly increased when believe P not responsible for their illness

ppl w high belief in just world helped more only when patient believed to be not responsible for illness

potential effects of receiving help- what is being looked at

the recipient

do people always want help

Wakefield, Hopkins, Greenwood (2012): study

female students made aware that women stereotyped by men as dependant, and then placed in situation where need help

asked to solve set of anagrams

those made aware of dependency stereotype less willing to seek help than control

those that did seek help felt worse the more help they sought

receiving help can be interpreted negatively if it confirms a negative stereotype about the recipient

therefore help may be rejected if reinforces negative stereotype

receiving help: backfire

prosocial behaviour can backfire

on tiktok, random acts of kindness

people subject to kindness can feel patronised and dehumanised

prosocial behaviour

acts that are positively viewed by society, includes helping behaviour and altruism

bystander effect

people less likely to help in an emergency when they are surrounded by other people than when they are alone

models to explain bystander effect or situation centred determinants of helping

bystander calculus model

latane and darley’s cognitive model

percivver centred determinants of helping

personality

mood

competence