BM Topic 3.4: Final Accounts

1/37

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

38 Terms

What are ‘final accounts’ & the 2 examples?

the published accounts of an organisation, made available to and used by different stakeholders (e.g. managers, employees, shareholders, sponsors, financiers, investors)

the profit & loss account (aka income statement)

the balance sheet (aka statement of financial position)

Who uses ‘final accounts’ & why?

internal stakeholders - include managers, employees, shareholders. can use the final accounts to gauge the performance of the business, in order to negotiate pay deals or to judge the level of job security

external stakeholders - include banks, suppliers, customers & the government. they’re interested in an organisation’s final accounts in order to enable them to make sensible & coherent decisions.

- e.g. financiers such as commercial banks & other lenders use the final accounts to evaluate the organisation’s ability to afford its debts (or borrowing)

*different stakeholders can also use the final accounts of an organisation in order to calculate various profitability & liquidity ratios

Why shareholders are interested in ‘final accounts’

measure whether the business is more or less profitable & how this has changed over time

measure the value of the business & judge whether this has increased over time

calculate the return on their investment (refer to profitability ratios)

determine how much dividends (share of the organisation’s profits) they receive

decide whether the organisation has prospects for growth & expansion

compare the financial performance of different businesses in order to make rational investment decisions (whether to buy or sell any shares in the company)

Why financiers are interested in ‘final accounts’

Decide whether to lend money to the business, and how much to lend, by judging the degree of risk involved.

Check on the creditworthiness of the organization before overdrafts or loans are given.

Assess the extent to which the business is able to pay back its borrowing (with interest).

Why suppliers are interested in ‘final accounts’

Assess whether the business has sufficient liquidity to pay its debts (trade credit).

Determine the creditworthiness of the business in order to gauge the level of risk involved.

Negotiate improved credit terms, such as deciding whether to extend the trade credit period or to demand immediate cash payment.

Why customers are interested in ‘final accounts’

Gauge whether a business is financially secure, especially if there is a long working capital cycle (a lengthy delay between the customers paying and receiving the products).

Determine whether the business offers security and reliability in its services; otherwise, customers will go elsewhere and purchase by rival suppliers.

Determine whether there will be future supplies of the product they are purchasing – this is particular important for customers that rely on a particular supplier or business.

Why the government is interested in ‘final accounts’

To calculate and check (verify) the amount of tax that is due to be paid by the business.

To measure the extent to which the business is able to expand and create jobs in the economy.

To assess the liquidity position of the business, in case there is a threat of business closure, which could cause serious economic problems (depending on the size of the business and the market in which it operates).

To ensure the business operates within the law, by adhering to the country’s accounting rules and laws.

Why competitors are interested in ‘final accounts’

Being able to compare their own financial accounts with the business in question, in order to judge their own financial performances.

Benchmark best practise by examining what the business does well, and determine how they themselves can improve.

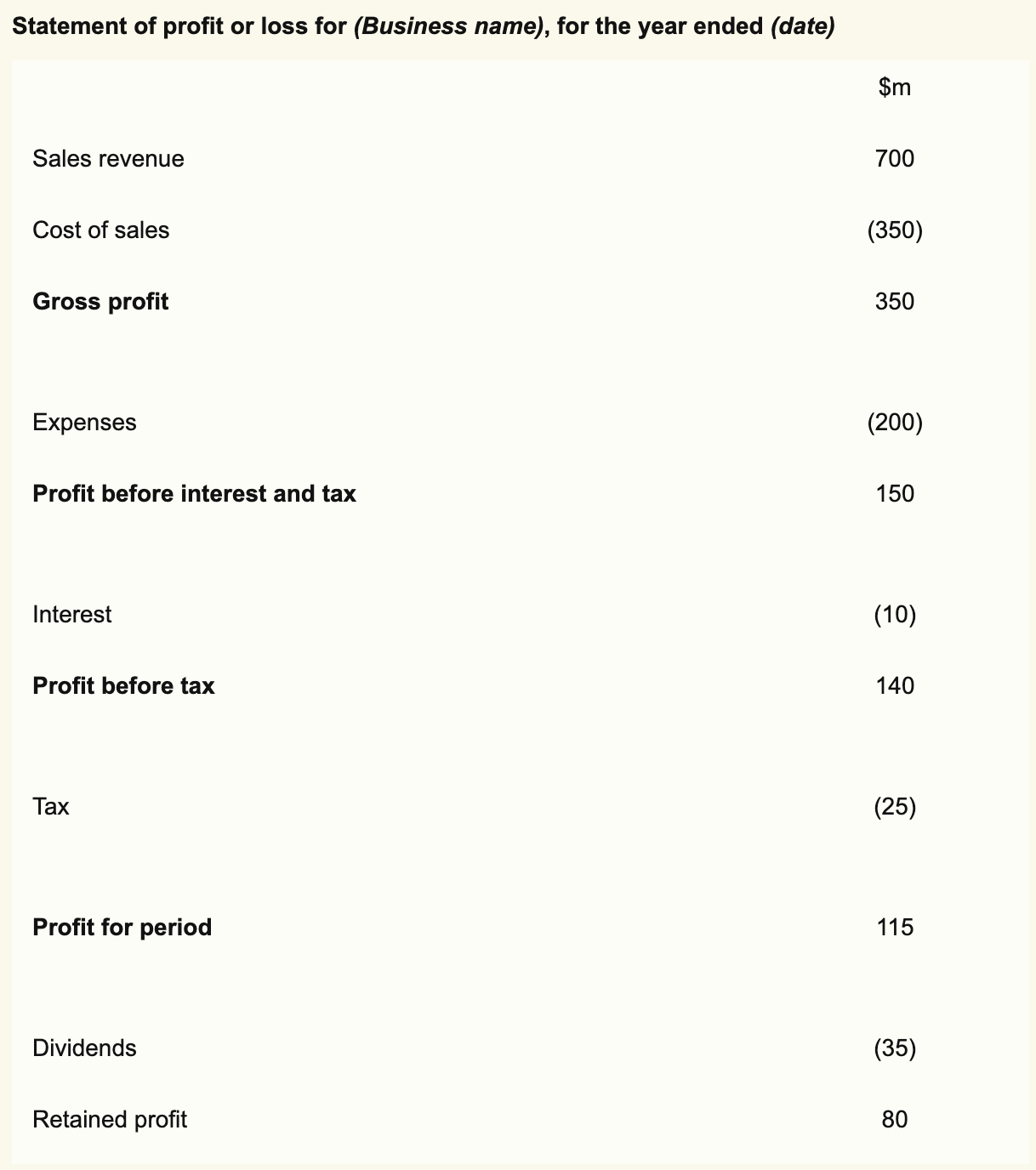

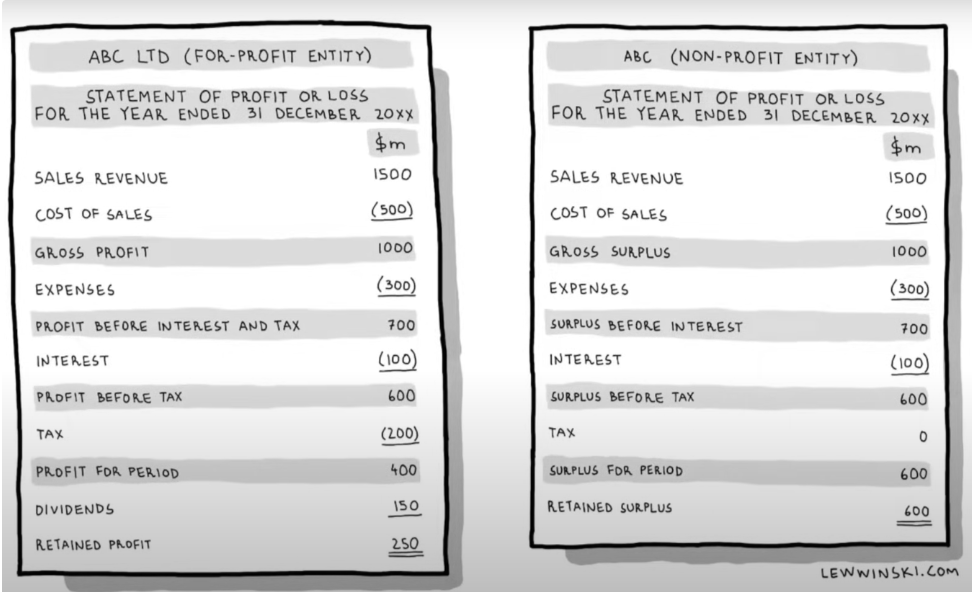

What is a ‘profit & loss statement (aka income statement)’?

shows a firm’s profit (or loss) after all production costs have been subtracted from the organisation’s revenues each year

Components of the profit & loss account

Sales revenue - money an organisation earns from selling goods or services. can also include other revenue streams

Costs of goods sold (COS/COGS): direct costs of productions AKA cost of goods sold (COGS) e.g. raw materials, component parts, direct labour

COGS = opening stock + purchases - closing stock

Gross profit - the profit from a firm’s everyday trading activities. the profit earned after subtracting the costs of producing goods & services from sales revenue by using the formula

gross profit = sales revenue - cost of goods sold

Expenses - firm’s indirect costs of production (e.g rent, management salaries, marketing campaigns, travel expenses, repairs & maintenance, etc)

** interest & tax not included in this section of P&LProfit before interest & tax - shows the value of a firm’s profit (or loss) before deducting interest payments on loans & taxes on corporate profits

Interest

Profit before tax

Tax

Profit for period - actual value of profit earned by the business after all costs have been accounted for (i.e. profit after interest & tax)

Dividends - payments from a company’s profit (after interest & tax) paid to shareholders (owners) of the company

Retained profit - any funds left over from profits (after interest & tax) that is not paid to shareholders & is kept within the business for its own use

***NOTE: for-profit entities → profit | non-profit entities → surplus instead of profit

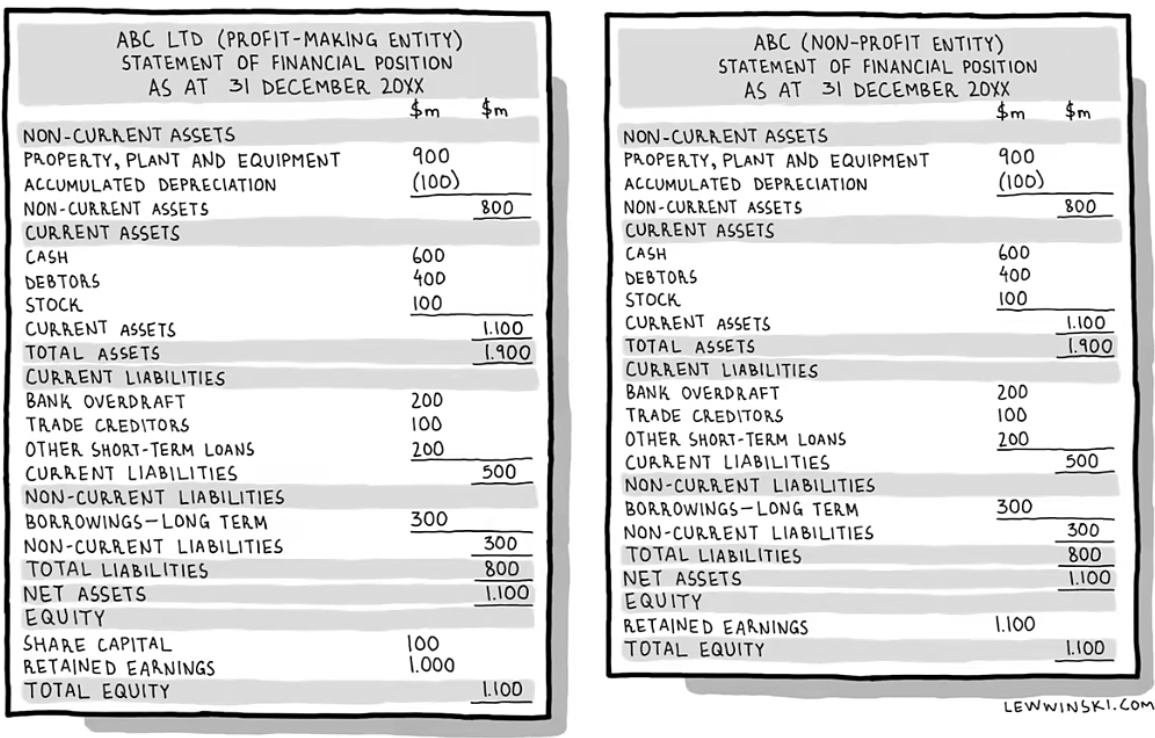

What is a ‘balance sheet (aka statement of financial position)’?

an essential set of final accounts that shows the value of an organisation’s assets, liabilities, and capital at a particular point in time.

- often referred to as a “snapshot” of a firm’s financial position, indicating its financial health

- the reporting date of the balance sheet for an organisation is the same each year

- legal requirement for all companies

- 3 parts: assets, liabilities, equity

- for the balance sheet to balance, value of net assets must equal value of its equity

- this is to ensure the firm’s total value of its sources of finance matches its uses of finance

2 important things a balance sheet must show

the organisation’s sources of finance, including borrowed funds (part of its liabilities) & equity (internal finance invested by shareholders, and any accumulated retained earnings)

the organisation’s uses of finance i.e. how it has used its sources of finance (e.g. purchase of non-current assets & current assets for trading)

Define ‘assets’

possessions of a business that have a monetary value & owned by the business.

e.g. buildings, land, machinery, equipment, stock (inventory), and cash.

Define ‘liabilities’

debts of a business i.e. money owed to others

e.g. money owed to financiers, trade creditors, government (corporation tax)

Define ‘non-current assets (fixed assets)’

long-term assets or possessions of an organisation with a monetary value, but are not intended for resale within the next twelve months of the balance sheet date.used over and over again as part of the organisation’s operations.

- generally highly illiquid assets → items of value owned by the business that cannot be sold quickly, are difficult to sell, and/or cannot be sold easily without incurring a significant loss in value

e.g. buildings, production facilities, equipment, machinery, vehicles

Define ‘current assets’

possessions of an organisation with monetary value but intended to be liquidated (turned into cash) within twelve months of the balance sheet date. this includes:

cash - the money an organisation has either “in hand” (at its premises) and/or “at bank” (in its bank account). cash is the most liquid of current assets & is easily accessible to the business

debtors - individual or business customers that owe money to the organisation because they have bought goods or services on trade credit

stocks (aka inventories) - goods a business has available for sale, per time period, intended to be sold as quickly as possible, thereby generating cash for the business. stocks can be categorized in 3 ways:

raw materials: natural resources used in the production process to create goods & provide services to customers

work-in-progess (aka semi-finished goods): parts & components of a final product in the production process. items in the process of being produced in order to sell to customers

finished goods: final products, ready for sale to customers. these products are of most value to customers

Define ‘total assets’

the sum of non-current assets & current-assets

Define ‘current liabilities’

short-term debts of a business, which need to be repaid within twelve months

bank overdrafts

trade creditors

short-term loans

Define ‘non-current liabilities’

long-term debts of a business, falling due after 12 months of the balance sheet date. refers to the long-term borrowings of the business (such as long-term loans & mortgages) aka long-term liabilities

Define ‘total liabilities’

sum of current liabilities & non-current liabilities (i.e. sum of all the money owed by the business)

Define ‘net assets’ & how to calculate

overall value of an organisation’s assets after all its liabilities are deducted

net assets = total assets - total liabilities

Define ‘equity’

the value of the owner’s stake in the business, i.e. what the business is worth at the time of reporting the balance sheet. comprised of both:

share capital: value of equity in a business that is funded by shareholders, either through an IPO or via a share issue

retained earnings: value of equity in a business that is funded by the accumulated profit after tax that has not been distributed as dividends to shareholders. instead, it’s kept as an internal source of finance for the business to use

retained earnings = opening retained earnings + profit after interest & tax for current period - dividends for current period

Define ‘intangible assets’ & 4 types of them

a type of fixed asset, except they are non-physical assets with monetary value to the business. these assets are protected by intellectual property rights

goodwill

patents

copyrights

trademarks

‘Goodwill’ as an ‘intangible asset’

the reputation & established networks (know-how) of an organisation, which adds significance above the market value of the firm’s physical assets

includes the willingness of employees to go above & beyond the call of duty as they are devoted to the organisation

can help entice workers to the organisation & to retain them

if included in a firm’s balance sheet, can help to attract investors

**however, value of goodwill is somewhat subjective (as the asset is intangible), so only truly materialises once the business is sold

‘Patents’ as an ‘intangible asset’

official rights given to a business to exploit an invention or process for commercial purposes. they give a registered patent holder the exclusive right to use the innovation for a limited time period.

having a patent creates incentives to invest in R&D, otherwise rivals could simply copy the innovations

add value to the business, especially as they gain from having a USP for the duration of the patent

‘Copyrights’ as an ‘intangible asset’

give the registered owner the legal rights to creative pieces of work. copyrights cover the work of authors, musicians, conductors, playwrights, directors. gives the copyright holder of the intellectual property exclusive rights to the commercial use of the product

enable owner to prevent competitors from using their published works

‘Trademarks’ as an ‘intangible asset’

form of intellectual property, the value of which may be reported on the balance sheet. give the listed owner the legal & exclusive commercial use of the registered brands, logos, and/or slogans (catchphrases)

Define ‘depreciation’ & how to measure it

refers to the fall in the value of a non-current asset. as a non-current asset is used over and over, its value drops due to wear and tear (usage & natural ageing or because they’re second hand), does not perform as well. in addition, newer & better models and/or improved technologies becomes available, further depreciating the value of older assets (may become obsolete) (e.g. computer equipment)

not materialised until the assets is actually sold, so there is no actual cash outflow when the value of a non-current asset declines over time

depreciation is recorded in the P&L account as a business expense & on the balance sheet to reflect the fall in the market value of the asset

failure to account for depreciation will result in the firm’s non-current assets being over-valued

the straight line method

the units of production method

Define ‘residual value (AKA scrap value AKA salvage value)’

the monetary value of a non-current asset at the end of its useful life, before it is replaced (essentially second hand value)

**in some cases, the degree of wear & tear or availability of newer technologies mean the residual value of the asset is zero

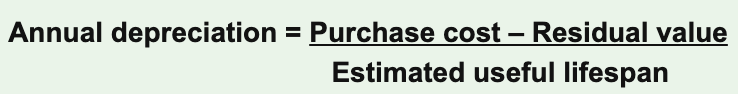

‘Straight line method’ to measure depreciation

spreads the depreciation evenly over the useful life of the non-current asset being depreciated. hence, value of the asset falls by equal amounts each year

the book value is the value of the asset that is recorded in the balance sheet. to calculate net book value (NBV):

net book value (NBV) = original cost of asset - accumulated depreciation

How to calculate ‘annual depreciation’

annual depreciation = (purchase cost - residual value) ÷ estimated useful lifespan

Advantages of using the ‘straight line method’ to measure ‘depreciation’

ease of calculating depreciation as the same amount is deducted each year. means that depreciation is treated as a fixed cost & does not change with the level of output or production

suitable for depreciating assets that have known useful shelf-life & can be estimated accurately

suitable for assets that have a consistent usage rate over the lifetime of the asset (e.g. furniture or automated machinery)

easier to depreciate value of assets until their scrap value is zero

same amount is charged to the profit & loss account each year, easier to make historical comparisons of the data

Disadvantages of using the ‘straight line method’ to measure ‘depreciation’

many non-currents assets (such as motor vehicles & computers) depreciate in value the most during the initial stages of their useful shelf life. hence, using a uniform depreciation value can be misleading & inaccurate

many assets do not depreciate consistently as they become less efficient over time. (e.g. machinery, computers & vehicles tend to have higher repair costs over time). this depreciation expense does account for (higher) maintenance costs over time

not suitable or useful if the functional life span of the asset cannot be estimated accurately

scrap values are only estimates of the future value of an asset. this makes the provisions for depreciation less accurate

‘Units of production method’ to measure depreciation & how to calculate (short overview)

calculates depreciation based on the units of usage rather than time (based on each physical unit of output)

- depreciation expense will be higher during years when there is a greater usage (due to favourable business activities) & lower during years when the asset is used less

- good to use for non-current assets such as delivery vehicles, photocopiers, coffee machines, etc

calculate the units of productions rate (AKA depreciation per unit)

calculate the depreciation expense

How to calculate ‘units of production method’ for ‘depreciation’

calculate the units of production rate (AKA depreciation per unit)

units of production rate = (cost of asset - salvage value) ÷ estimated units of production

calculate the depreciation expense

depreciation expense = units of production rate x actual units produced

Advantages of using the ‘units of production method’ to measure ‘depreciation’

for many businesses, more realistic & accurate to use this method to depreciate the value of an asset due to its usage than just the passage of time

in particular, works well for businesses that use machinery or capital equipment to manufacture a product

method is more accurate for non-current assets that depreciate directly due to wear and tear, rather than the passage of time which eventually makes the product obsolete

useful for manufacturers that experience fluctuations in production, based on changes in consumer demand over time. hence, depreciation is treated as a variable to direct cost that changes with the level of output or production

Disadvantages of using the ‘units of production method’ to measure ‘depreciation’

more complicated to calculate than the straight line method of depreciation

some degree of subjectivity as the salvage value is subject to change & the estimated units of production is also only an estimate. over or under-estimating the figures will make the depreciation expense less accurate

many tax authorities do not allow the units of depreciation method to be used for tax purposes. hence, this method is primarily used for internal accounting records