Newton's first law of motion: Reading

1/25

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

26 Terms

Inertia

the property of things to resist changes in motion

newton’s first law of motion (the law of inertia

every object continues in a state of rest or of uniform speed in a straight line unless acted on by a nonzero net force

force

in teh simplest sense a push or pull

net force

the vector sum of forces that act on an object

vector

an arrow drawn to scale used to represent a vector quantity

vector quantity

a quantity that has both magnitude and direction, such as force

scalar quantity

a quantity that has magnitude but not direction such as mass and volume

resultant

theh net result of a combination of two or more vectors

mechanical equilibrium

the state of an object or system of objects for which no charges are in motion. According to Newton’s first law, if an object is at rest, the state of rest persists. if an object is moving its motion continues without charge

equilibrium rule

For any object or system of objects in

equilibrium, the sum of the forces acting equals zero. In

equation form, gF = 0.

Aristotle on Motion

Aristotle divided motion into two main classes: natural motion and violent motion.

Aristotle asserted that natural motion proceeds from the “nature” of an object, dependent on the combination of the four elements (earth, water, air, and fire) the object contains.

Aristotle stated that heavier objects would strive harder and argued that objects should fall at speeds proportional to their weights: The heavier the object, the faster it should fall.

Aristotle stated that heavier objects would strive harder and argued that objects should fall at speeds proportional to their weights: The heavier the object, the faster it should fall. Natural motion could be either straight up or straight down, as in the case of all

Aristotle believed that different rules apply to the heavens and asserted that celestial bodies are perfect spheres made of a perfect and unchanging substance, which he called quintessence.

Aristotle and violent motion

Violent motion, Aristotle’s other class of motion, resulted from pushing or pulling forces.

Violent motion was imposed motion. A person pushing a cart or lifting a heavy weight imposed motion, as did someone hurling a stone or winning a tug-of-war.

The concept of violent motion had its difficulties because the pushes and pulls responsible for it were not always evident.

For example, a bowstring moved an arrow until the arrow left the bow; after that, further explanation of the arrow's motion seemed to require some other pushing agent

The arrow was propelled through the air as a bar of soap is propelled in the bathtub when you squeeze one end of it.

In summary: Aristotle

Aristotle taught that all motions are due to the nature of the moving object or due to a sustained push or pull. Provided that an object is in its proper place, it will not move unless subjected to a force. Except for celestial objects, the normal state is one of rest. Aristotle’s statements about motion were a beginning in scientific thought, and, although he did not consider them to be the final words on the subject, his followers for nearly 2000 years regarded his views as beyond question. Implicit in the thinking of ancient, medieval, and early Renaissance times was the notion that the normal state of objects is one of rest. Since it was evident to most thinkers until the 16th century that Earth must be in its proper place, and since a force capable of moving Earth was inconceivable, it seemed quite clear to them that Earth does not move.

Copernicus and the moving earth

It was in this intellectual climate that the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) formulated his theory of the moving Earth.

Copernicus reasoned that the simplest way to account for the observed motions of the Sun, Moon, and planets through the sky was to assume that Earth (and other planets) circles around the Sun.

Most of us know about the reaction of the medieval Church to the idea that Earth travels around the Sun.

Aristotle’s views had become a formidable part of Church doctrine, so to contradict them was to question the Church itself.

For many Church leaders, the idea of a moving Earth threatened not only their authority but the very foundations of faith and civilization as well.

Galileo’s experiments: Leaning tower

It was Galileo, the foremost scientist of the early 17th century, who gave credence to the Copernican view of a moving Earth.

He accomplished this by discrediting the Aristotelian ideas about motion.

Galileo easily demolished Aristotle’s falling-body hypothesis.

Galileo is said to have dropped objects of various weights from the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa to compare their falls.

Contrary to Aristotle’s assertion, Galileo found that a stone twice as heavy as another did not fall twice as fast.

Except for the small effect of air resistance, he found that objects of various weights, when released at the same time, fell together and hit the ground at the same time.

On one occasion, Galileo allegedly attracted a large crowd to witness the dropping of two objects of different weight from the top of the tower.

Galileo’s experiments: Inclined planes

Galileo was concerned with how things move rather than why they move

He conducted expirements Based more on logic

Motion always involved a resistive medium such as air or water. He believed a vacuum to be impossible and therefore did not give serious consideration to motion in the absence of an interacting medium.

That’s why it was basic to Aristotle that an object requires a push or pull to keep it moving.

And it was this basic principle that Galileo rejected when he stated that, if there is no interference with a moving object, it will keep moving in a straight line forever; no push, pull, or force of any kind is necessary

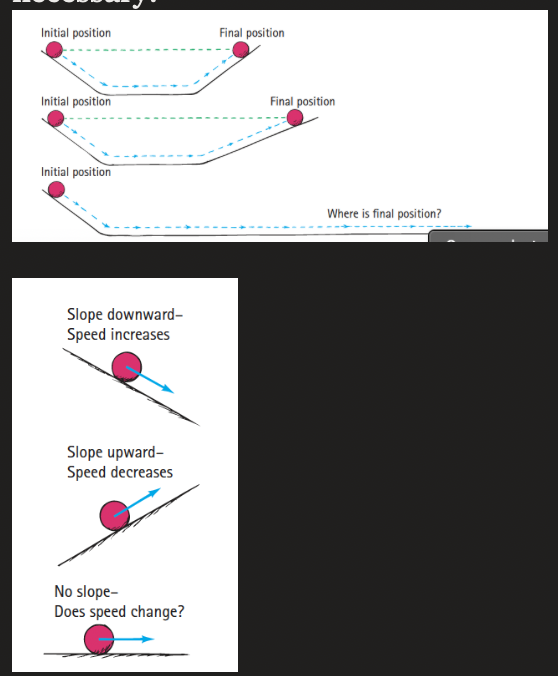

Galileo tested this hypothesis by experimenting with the motions of various objects on plane surfaces tilted at various angles.

He noted that balls rolling on downward-sloping planes picked up speed, while balls rolling on upward-sloping planes lost speed.

galileo’s experiments: inclined planes - final findings and reasoning

From this he reasoned that balls rolling along a horizontal plane would neither speed up nor slow down. The ball would finally come to rest not because of its “nature,” but because of friction.

This idea was supported by Galileo’s observation of motion along smoother surfaces: When there was less friction, the motion of objects persisted for a longer time; the less the friction, the more the motion approached constant speed.

He reasoned that only friction prevented it from rising to exactly the same height, for the smoother the planes, the closer the ball rose to the same height.

galileo’s experiments: inclined planes - adjustments to the experiments

Then he reduced the angle of the upward-sloping plane.

Again the ball rose to the same height, but it had to go farther.

Additional reductions of the angle yielded similar results; to reach the same height, the ball had to go farther each time.

He then asked the question, “If I have a long horizontal plane, how far must the ball go to reach the same height?” The obvious answer is “Forever—it will never reach its initial height.”2

If it moves up a steep slope, it loses its speed rapidly.

On a lesser slope, it loses its speed more slowly and rolls for a longer time.

The less the upward slope, the more slowly the ball loses its speed.

Galileo’s experiment: inclined planes findings

In the extreme case in which there is no slope at all—that is, when the plane is horizontal—the ball should not lose any speed.

Galileo’s concept of inertia discredited the Aristotelian theory of motion.

Aristotle did not recognize the idea of inertia because he failed to imagine what motion would be like without friction.

Newton’s first law of motion

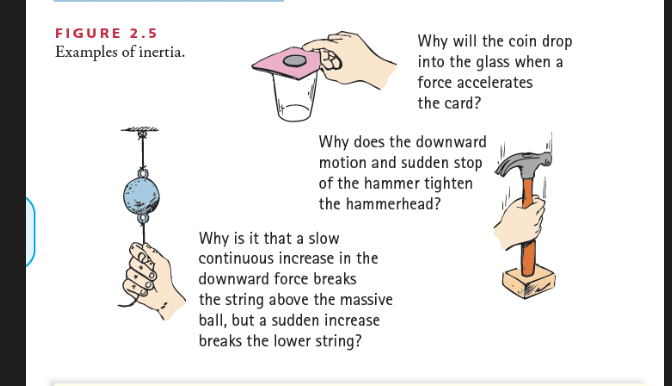

The tendency of things to resist changes in motion was what Galileo called inertia. Newton refined Galileo’s idea and made it his first law, appropriately called the law of inertia.

Every object continues in a state of rest or of uniform speed in a straight line unless acted on by a nonzero net force.

The key word in this law is continues: An object continues to do whatever it happens to be doing unless a force is exerted upon it. If it is at rest, it continues in a state of rest.

If an object is moving, it continues to move without turning or changing its speed.

This is evident in space probes that continuously move in outer space.

Changes in motion must be imposed against the tendency of an object to retain its state of motion.

In the absence of net forces, a moving object tends to move along a straight-line path indefinitely.

Net Forces and Vectors

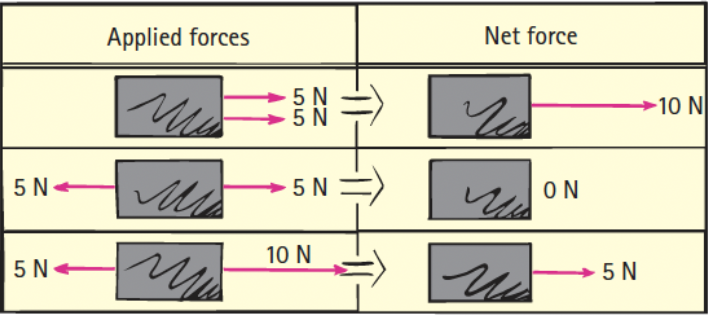

Changes in motion are produced by a force or combination of forces (in the next chapter we’ll refer to changes in motion as acceleration).

A force, in the simplest sense, is a push or a pull. Its source may be gravitational, electrical, magnetic, or simply muscular effort.

When more than a single force acts on an object, we consider the net force.

For example, if you and a friend pull in the same direction with equal forces on an object, the forces combine to produce a net force twice as great as your single force.

If you both pull with equal forces in opposite directions, the net force is zero.

The equal but oppositely directed forces cancel each other.

Net Forces and Vectors part 2

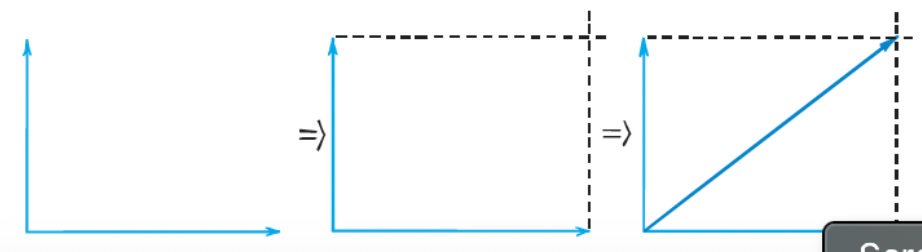

Any quantity that requires both magnitude and direction for a complete description is a vector quantity (Figure 2.7).

Examples of vector quantities include force, velocity, and acceleration.

By contrast, a quantity that can be described by magnitude only, not involving direction, is called a scalar quantity.

Mass, volume, and speed are scalar quantities

Adding vectors that act along parallel directions is simple enough: If they act in the same direction, they add; if they act in opposite directions, they subtract.

The sum of two or more vectors is called their resultant.

Force Vectors

The parallelogram rule shows that the tension in the right-hand rope is greater than the tension in the lefthand rope. If you measure the vectors, you’ll see that the tension in the right rope is about twice the tension in the left rope. Both rope tensions combine to support Nellie’s weight.

Equilibrium Rule

Note that there are two forces acting on the bag of flour—tension force acting upward and weight acting downward.

The two forces on the bag are equal and opposite, and they cancel to zero. Hence, the bag remains at rest.

In accord with Newton’s first law, no net force acts on the bag.

We can look at Newton’s first law in a different light—mechanical equilibrium.

Equilibrium force part 2

When the net force on something is zero, we When the net force on something is zero, we say that something is in mechanical equilibrium.5 In mathematical notation, the equilibrium rule is gF = 0 The symbol g stands for “the vector sum of” and F stands for “forces.

For a suspended object at rest, like the bag of flour, the rule says that the forces acting upward on the object must be balanced by other forces acting downward to make the vector sum equal to zero.

(Vector quantities take direction into account, so if upward forces are + , downward ones are - , and, when added, they actually subtract.)

Support force

Consider a book lying at rest on a table. It is in equilibrium. What forces act on the book?

One force is that due to gravity—the weight of the book. Since the book is in equilibrium, there must be another force acting on the book to produce a net force of zero—an upward force opposite to the force of Earth’s gravity.

The table exerts this upward force.

We call this the upward support force. This upward support force, often called the normal force, must equal the weight of the book.6 If we call the upward force positive, then the downward weight is negative, and the two add to zero.

The net force on the book is zero. Another way to say the same thing is gF = 0.