sbarra - technology and relationships

1/31

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

32 Terms

sbarra purpose

Proposes an evolutionary mismatch between humans’ evolved intimacy mechanisms (self-disclosure, responsiveness) and the affordances of smartphones and social media.

Argues that smartphones activate social instincts in maladaptive ways, leading to technoference—interference of technology in social interactions.

evolutionary mismatch

When modern environments trigger ancient adaptive behaviors in ways that are no longer beneficial.

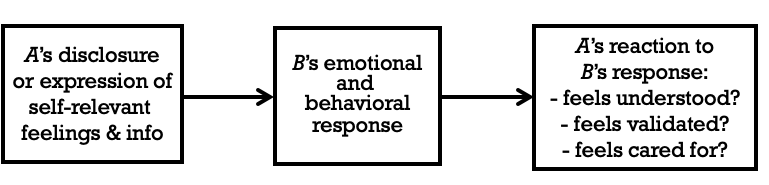

Self-disclosure & responsiveness

Core intimacy processes evolved to build trust and cooperation in small, face-to-face groups.

Technoference

Everyday disruptions in relationships due to technology use (e.g., partner phubbing, divided attention).

sbarra main argument

Smartphones cue ancestral drives for social bonding, but across vast virtual networks rather than small, intimate groups.

These cues draw attention away from real-time interactions, impairing responsiveness and intimacy.

Over time, this can undermine relationship quality, emotional well-being, and even health.

sbarra theoretical framework

Rooted in attachment theory and evolutionary psychology.

Attachment behaviors (trust, responsiveness) evolved to solve survival problems in small kin groups.

Modern technology “hijacks” these mechanisms, offering superficial connection instead of deep intimacy.

cognitive disruption - path 1

Smartphone presence reduces attention, working memory, and task performance (e.g., Ward et al., 2017).

Notifications alone can impair focus and sustained attention (Stothart et al., 2015)

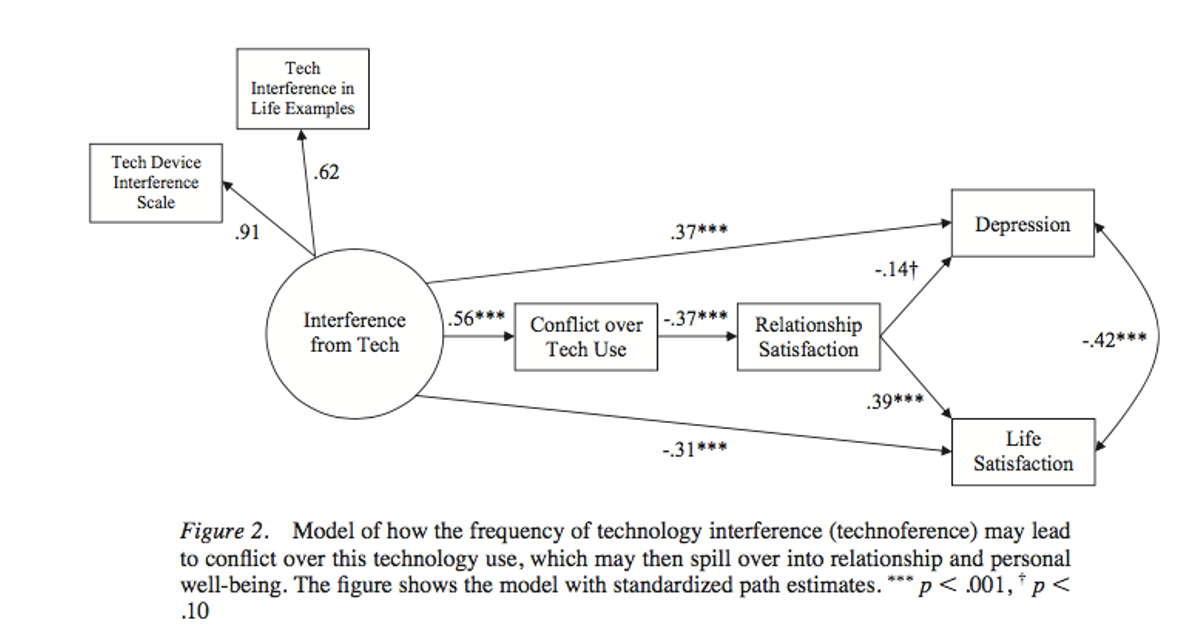

relational disruption (path 2-3)

Mere presence of a phone reduces perceived empathy and connection in conversations (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2013; Misra et al., 2016).

Phubbing (phone snubbing) predicts more conflict and lower relationship satisfaction (Roberts & David, 2016).

Texting frequency predicts decreased satisfaction one year later (Halpern & Katz, 2017).

Parent technoference linked to children’s internalizing/externalizing behavior problems (McDaniel & Radesky, 2018).

well-being outcomes (path 4-5)

Facebook and SNS use associated with decreased life satisfaction and well-being over time (Kross et al., 2013; Shakya & Christakis, 2017).

Partner phubbing linked to higher depression, mediated by lower relationship satisfaction (Wang et al., 2017).

Smartphone dependence predicts relational uncertainty and reduced trust (Lapierre & Lewis, 2018).

mechanisms sbarra

Smartphones create competition for attentional resources, undermining responsiveness.

They blur boundaries between intimate networks and extended social networks, spreading intimacy processes too thin.

Frequent shallow interactions (“social snacking”) substitute for deeper in-person bonds.

health and attachment links sbarra

High-quality relationships promote health, stress regulation, and longevity.

Disruptions to intimacy processes may therefore have indirect health costs.

implications sbarra

Smartphones are not inherently harmful; their timing and context of use determine their effects.

Relationship interventions should emphasize mindful technology use and presence during interactions.

Calls for a multilevel research agenda linking cognition, intimacy, and technology.

limitations sbarra

Evidence mostly correlational or cross-sectional.

Cultural variation and longitudinal impacts underexplored.

Overlaps between positive and negative uses of technology need clearer boundaries.

sbarra conclusion

Smartphones reshape social behavior by exploiting ancient social instincts.

The resulting evolutionary mismatch may erode real-world intimacy and satisfaction.

Understanding technoference is essential for promoting healthy relationships in a digital world.

our evolved need for intimacy

Human beings have a fundamental and evolved need to form close attachments with others

In ancestral environments, the capacity to form intimate, trusting relationships was highly beneficial to one’s survival

It is clear from archaeological records and cross-species comparison is that human brains not only evolved to deal with the immense complexities of social relationships, but that they were especially well designed for navigating close and intimate relationships with non-kin.

the interpersonal process model of intimacy

intimate relationships

functioned as a security network that provided the individual with unspoken and unquestioning support. On average, people have between 3 and 7 people with whom they interact at high levels of intimacy, about half of whom are usually non-kin

are characterized by a deep sense of emotional closeness toward another person and usually are characterized by frequent, strong and diverse contact

depended on face-to-face contact and frequent reaffirmation, and it is from their intensity that individuals derived security—security that one could trust that those in their intimate network would be there in times of trouble and that they would not be excluded from the group

effective networks

include friends and relatives (around 20 people). Provided emotional and material assistance in daily life—not as emotionally deep as intimate network members but still people with whom one would spend substantial face-to-face time on a regular basis. Size of effective network depended on the necessities of maintaining face-to-face relationships.

extended networks

(around 150 people) included acquaintances and friends of friends. Required little face-to-face contact. Would have included entire tribes of people, including those one barely knew and distant kin.

The size of this in ancestral times is mirrored today in the typical size of one’s online social network

recent usage stats

Over 77% of all Americans own a smartphone, including 92% of those aged 18-29. They use them for 5 hours per day on average

Much of that time is spent on social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Worldwide, people spent an average of 135 minutes per day on social media in 2017

Online time is negatively correlated with time spent going to parties, attending cultural events, and socializing with people in a variety of offline contexts

smartphones hijack evolutionary needs for self disclosure and responsiveness

The main function of social media is to share facts and one’s thoughts and feelings (or photos or links to articles) to a large number of people and, in turn, for those in one’s online social network to respond.

Social networks are self-disclosure vehicles: 80% of social media activity involves simply announcing one’s immediate experiences

People can also be responded to (or ignored) by an infinite number. All of the social media platforms are designed to produce easy and frequent responsiveness via ”likes”, tiny hearts, stars, etc.

Smartphone notifications beckon us to respond to them.

evolutionary mismatch theory

1.Humans have an evolved need for intimacy and, therefore an evolved need for self-disclosure and responsiveness

2.Smartphones and their affordances (access to social networks, texting, etc.) exert a strong pull for self-disclosure and responsiveness

3.Smartphones and their affordances are at odds with our evolved needs for intimacy (i.e., a mismatch)

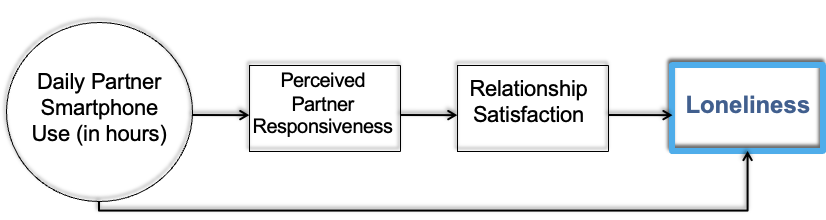

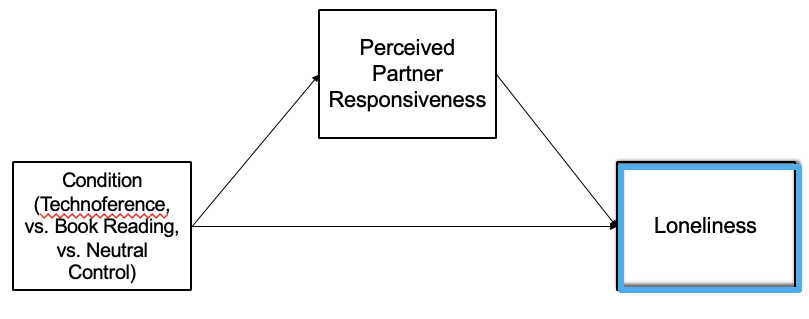

responsiveness as a mediator of the links of technoference: loneliness

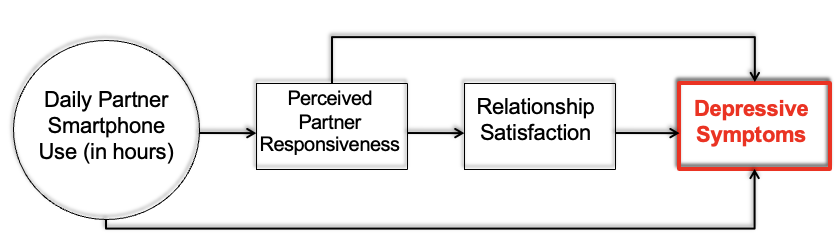

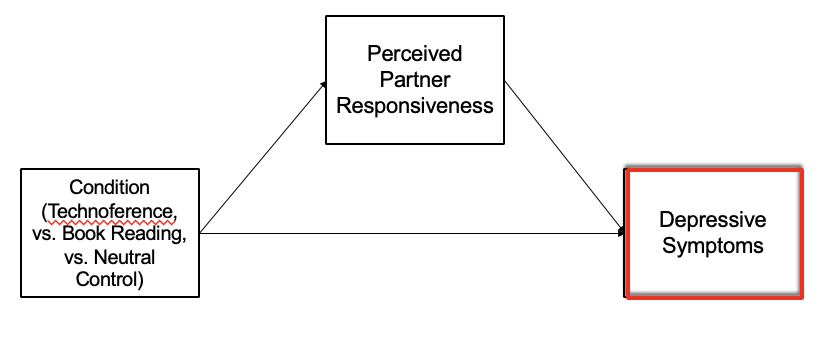

responsiveness as a mediator of the links of technoference: depression

experimental findings loneliness

experimental findings depression

dyadic daily diary study

no significant effects of smartphone use on responsiveness

no significant effects of technoference on responsiveness

takeaways of phone responsiveness findings

Correlational and experimental data show that perceptions of greater partner phone use are associated with lower levels of perceived partner responsiveness, satisfaction, etc.

People perceive that partners’ phone use makes them feel worse, but only slightly more so (if at all) than reading a book

NO effects of objective daily phone use on responsiveness, loneliness, well-being, etc.

concerned experts and parents

have been concerned about everything

radio, tv, books, telephones, video arcades

what you should know based on what researchers know

Anxiety about the negative effects of social media has risen to such an extreme that using a smartphone is sometimes equated to ingesting a gram of cocaine. The reality is much less alarming.

A close look at social media use shows that most texters and Instagrammers are fine. Many early studies and news headlines have overstated dangers and omitted context.

Researchers are now examining these diverging viewpoints, looking for nuance and developing better methods for measuring whether social media and related technologies have any meaningful impact on mental health.

why be aware?

Because simply using the phone or being on social media does not seem to be the problem, it’s how the phone use impacts other aspects of life that could (potentially) be problematic

signs to be aware of

You feel disconnected from your friends, especially if you feel depressed

Most recent data: people who are depressed seek out social media more and use their phone (slightly) more rather than vice versa

When the phone supplants rather than fosters in-person relationships

Not all screen time is the same

When the phone gets in the way of sleep

adults typically need 7-8 hours of sleep

When the phone gets in the way of schoolwork/grades