Anticancer - oncogene specific therapies

1/48

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

49 Terms

Designing drugs to target cancer

Identify the difference between cancer cells and normal cells:

Molecular events

Phenotypic changes, as a consequence of molecular events

Current drugs we have target these 2 areas:

Cytotoxic drugs usually target the faster-growing nature/phenotypically different cells

Molecular target drug targets the changes that take place leading to cancer and tend to be more specific

Cancer cells rely on oncogenes and the production of their “surviving signals” —> known as oncogene addiction

if we remove these surviving signals, this is one of the methods to selectively treat cancer

But cancer cells will try and reestablish and use other surviving signals, known as resistance

For some patients, we don’t know the molecular mechanism that leads to their cancer, so treatment can be less specific and more challenging

Cell culture

Use 3D chromatogel culture to mimic the cell in vivo better compared to 2D culture

Breast epithelial cells in culture usually look round and symmetrical (top right); however, the cancerous cells are asymmetrical with lots of protrusions (bottom left)

The other two samples are not normal either: the one on the top right has a tumour suppressor gene knockout while the bottom left has an activation of an oncogene

Shows that there is more than one types of mutations needed to induce cancers and more than one type of cancer

For example: If you wanted to treat the bottom left sample you could simply knock out the oncogenes as they’re reliant on this

Oncogenes and Tumou supressor genes

Two types of cancerous genes

Oncogenes – genes which drive the tumour phenotype expression that the cells are reliant on

Tumour suppressor genes – prevent the formation of tumours

To fully transform into a cancerous cell, you need two events to fully transform cells from normal to cancer cells

This also allows for selective targeting of cancer cells

Selective Toxicity

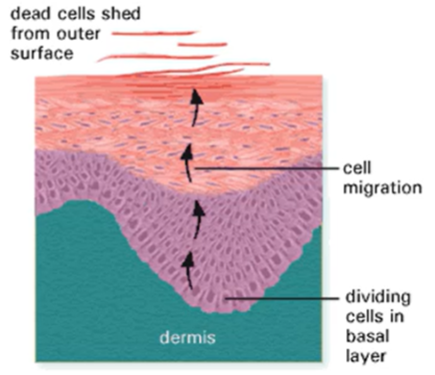

Diseased cells have similar properties to normal cells (especially those in bone marrow, hair, GI mucosa and skin)

If we target these fast-growing sites we will have consequences in the form of side effects:

If we target bone marrow cells will impact the immune system —> anaemia or susceptibility to infection

If we target hair cells will cause hair loss

We need to look for “windows of opportunity” where cancer cells are especially vulnerable to avoid damage to our cells

Precision medicine

Instead of grouping the patients by the organ of their cancer, can group patients by their molecular signature, indicative of the driving events leading to the cancer

Can create more efficacy and selective toxicity

Can also apply this to other diseases, such as diabetes

How can we selectively target cancer cells

PTEN tumour suppressor genes

PTEN+ cells normal cells with tumour suppressor, PTEN- cancerous cells with no tumour suppressor

Mixed in a 1:1 ratio and can knock down genes individually, can treat the cells with a drug or siRNA library and observe the outcome

The siRNA targets specific mRNA and degrades it creating a knockout of each gene

Can see if the specific gene knockout affects the cancer cells, the normal cells or both

Additionally, you can do this with a drug library instead of knocking out the genes with siRNA libraries

Through this technique was able to identify the gene WDHD1 if knocked out, it selectively inhibits or kills PTEN. Targeting these genes can selectively target this type of breast cancer

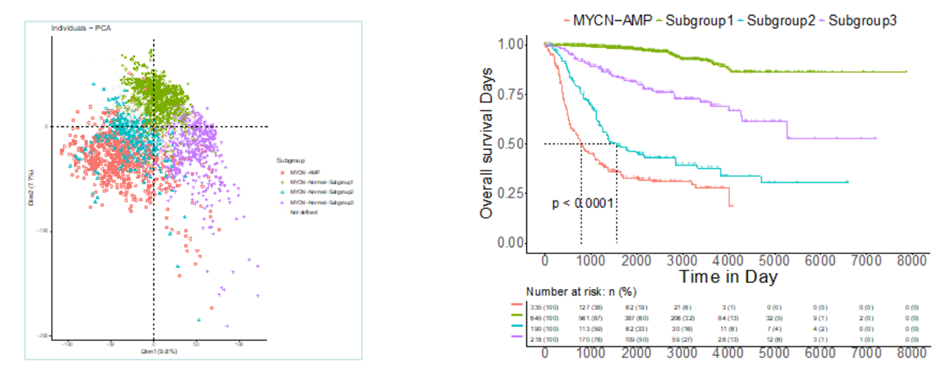

Transcriptomic Profiling

Another technique of categorising patients for selective treatment, but instead of wet lab can use bioinformatics

Can group cells from their molecular signatures

Examined neuroblastoma patients and examined the overall survival rate

Can help you categorise the molecular markers into high or low risk cancers

The green profile patients had a high overall survival rate without any treatment —> suggests that their cancer type is low risk

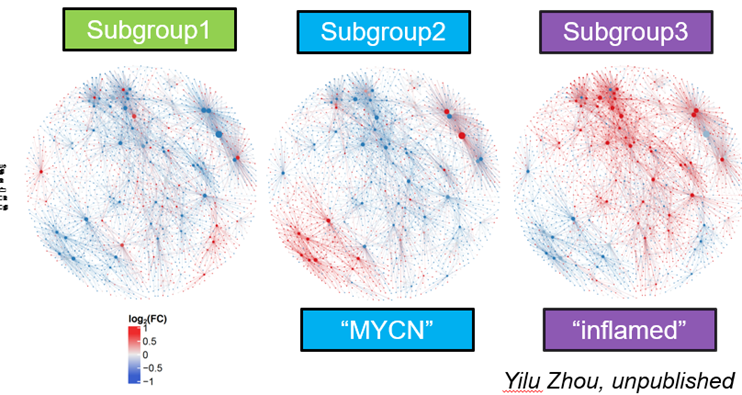

Can also create maps which hotspot the molecular events which occur, leading to that cancer.

Red signals indicate oncogenic signals, and were associated with the aggressive, high mortality rate cancers, supporting the idea that we can group patients based off their gene expression profiles

Can then create therapeutic targets which help to specifically target these molecular events that lead to cancer

Success of current treatments

Surgery is not likely a viable treatment method for melanoma as it spreads all over the body in many tumours

Can understand the oncogene activation and block the oncogene pathway to target the cancer cells using a drug

However, after a few rounds of treatment, the cancer returns due to their ability to reestablish surviving treatments (called drug resistance)

Molecular basis of cancer

Normal cell growth and cancer

Cancer cells have altered genomes

Mutations

Oncogenes and Tumour supressing genes

Hallmarks of cancer

sustaining proliferative signals

evading growth supressors

avoiding autoimmune destruction

enabling replicative immortality

tumour promoting inflammation (enabling characteristric)

activating invasion and metastasis

inducing or accessing vasculature

genome instability and mutation (enabling characteristic)

resisting cell death

degrading cellular metabolism

these are some of the commonly observed features of cancer cells which give them the enabling characteristics that enable their development and survival

plasticity of cancer cells

unlocking phenotypic plasticity is a crucial component for the cancer pathogenesis and allows cells to escape normal differentiation programmes —> which gives cancer cells the ability to initiate, metastasise, develop therapy resistance

ways which this occurs:

loss of transcription factors such as HOXA5 allow cells to dedifferentiate

Blocking differentiation, for example, through the expression of SOX10

trans differentitaion where the cell is able to transform into an entirely different lineage

epigentic changes

mutations in gnes which organise chomatin architecture can drive epigentic changes known as “nonmutational programming”

these epigentic changes can drive the cancer to enter drug tolerant states where they reduce proliferation, alter their surviving signals and increase their stress tolerance —> resistance

Can also drive them to reduce drug penetration, drive them to undergo plasticity mechanisms or gneerate intratumoural heterogeneity which is a bet hedging technique which allows cancer cells to adapt rapidly in the prescence of a stressor

Normal cell growth and cancer

Usually, there's a fine balance between apoptosis and proliferation for normal cell growth

In cancer the events of oncogene activation result in more proliferation or less apoptosis

The removal of the tumour suppressor genes prevent these cells from being targeted

Classification of cancers

Neoplasia – excess proliferation without relation to normal growth or repair. Growth may be fast but rarely exceeds that in the fastest growing tissues

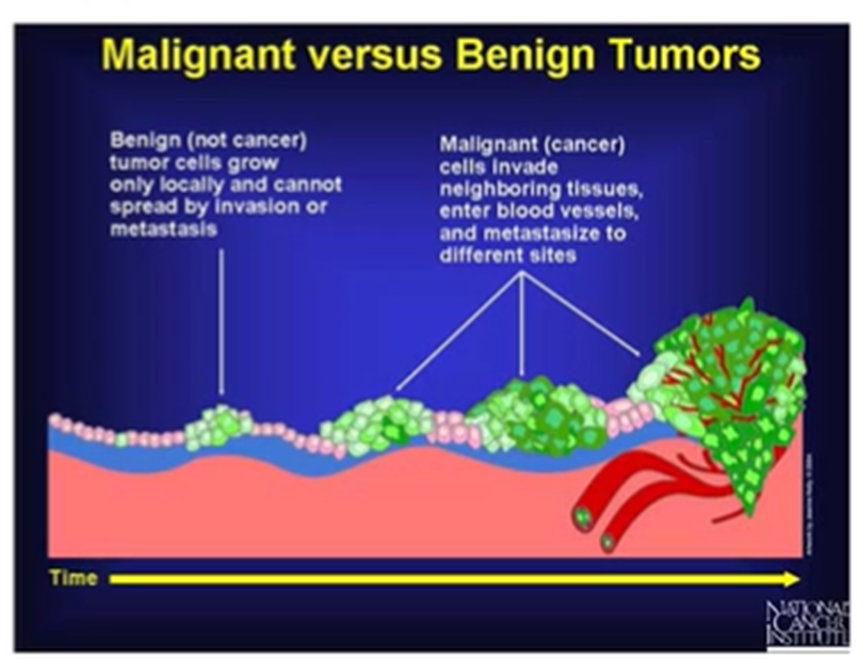

Benign – called a tumour rather than cancer. Proliferate locally and retain characteristics, have a defined boundary.

Malignant – Not encapsulated, ill defined edge, projections extend into surrounding tissues, less well differentiated than the cells of origin. Spread to other sites by invading surrounding tissues

Can also develop from benign to malignant:

Altered genome of cancer cells

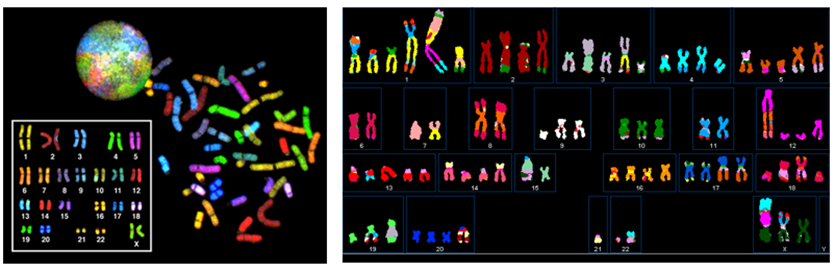

Karyotypes can detect the changes in genomes that occur in cancer

Karyotypes of cancer genome have:

Different number of chromosomes —> more or less copies

Translocated DNA across the chromosomes causing mutated chromosome shape

Lost DNA

Chromosomes might start with small chromosome altering events but as the cancer develops accumulate changes leading to chromosome instability

Mutations

Germline mutations

A change in the DNA sequence that can be inherited from either parent

Occurs in all the cells

Somatic mutation

A change in the DNA sequence in cells other than sperm or egg

The mutation is present in the cancer cells and its offspring but not in the patient's healthy cells

Occurs only in the tumour cells

Most mutations causing oncogene activation will be point mutations, while in tumour supressor genes will be frameshift

Hereditary Predisposition

If generations before you in your family had cancer doesn’t mean you’ll inherit it —> some familial mutations that you will inherit, but only 5% of cancers are hereditary

Loss of tumour suppressor genes will result in a higher chance of cancer —> For cancer to occur you need multiple events and this is one of them

Don’t necessarily have cancer, but they have a higher chance of having cancer later in life as we have 2 tumour suppressor genes, it's likely that you’ll have at least one healthy copy.

Transformation of cells to cancer cells

For normal cells to transform into cancer cells 2 events need to happen (hallmarks of cancer cells)

Activation of oncogene

Inactivation of tumour suppressor gene

This offers the cancer growth advantages compared to other cells

Also creates therapeutic targets —> once we understand these therapeutic events we can target these mechanisms

We won’t target normal cells because they’re not addicted to the oncogenes

Events leading to transformation of cells BRCA

Somatic or germline mutations in the tumour suppressor genes

BRCA important for damage repair in the DNA, therefore loss of BRCA results in high chance of breast or ovarian cancer

Once the tumour cells have lost BRCA they can rely on POP to repair the damages —> we can target POP with AntiPOP inhibitors

In most cases those with BRCA mutations have no family history —> developed over their lifetime.

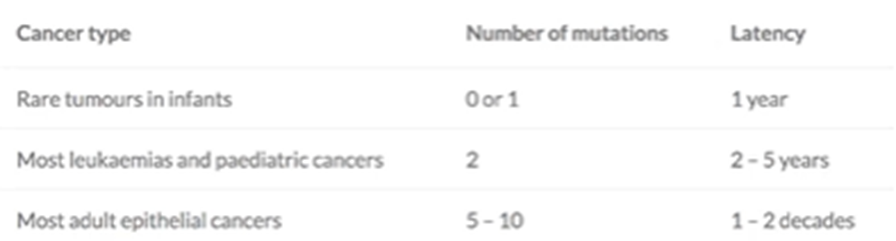

Origins of cancer

Most tumours require multiple mutations, but this can vary

E.g: white blood cell cancers only need one mutation whereas epithelial cell cancers need multiple —> this is because for an epithelial cell they need multiple mutations to develop the properties to proliferate, then grow out of the space etc. however, white blood cells don’t need many events as they’re already highly proliferative and are already circulated around the body

Car Crash Theory

Oncogenes are like the engines which drive the cell cycle (the car)

Tumour suppressor genes are like brakes that prevent the crash – in the absence, these mutations are not repaired and allow them to be passed onto other cells and accumulate

For cancer you need both events

Events causing colon cancer (adenocarcinoma)

Loss of APC (tumour suppressor) involved in Wnt signalling activates the oncogenic pathway

At this point is not a cancer, only a tumour as its not yet invasive

Next is the activation of KRAS is the activation of the oncogene and drives the progression from an early adenoma to a late adenoma

Next is the loss of p53 which allows the tumour cell to acquire multiple mutations to drive the cancer.

Progression of late adenoma to adenocarcinoma which has invasive properties

We need the loss of the tumour suppressor early on to allow the mutations to accumulate

p53

Can decide whether damage can be reversed or repaired —> whether the cell survives or dies

Most cancers actually have increased rates of apoptosis but due to the sheer amount of proliferation the net result is growth

Loss of function p53 results in more cell survival, whereas overactive p53 results in unnecessary cell death, resulting in ageing, neurodegenerative disease or radiation sickness

Elephants have 40 copies of p53 while we only have 2, so despite having more cells can better control the progression of cancer

p53 is only activated under severe stress which is why the mutations have been allowed to accumulate up to this point. Additionally, p53 favours DNA repair and cell cycle arrest over apoptosis —> when it’s lost the cell cycle no longer arrested and mutations passed onto daughter cells

Examples of key oncogenes - Ras

Mutations in Ras responsible for a majority of cancers

3 isoforms of ras – k,h,m Ras

Ras activity is controlled by GDP or GTP bound

When GTP bound it will be able to bind to Raf or PI3K

PI3K causes activation of AKT

While activation of Raf causes activation of ERC signalling pathways

Ras can also be activated by upstream factors like EGFR

Very regularly mutated pathway in cancer

EGFR highly mutated in lung cancer

Raf oncogene for melanoma

K Ras oncogene in pancreatic cancer

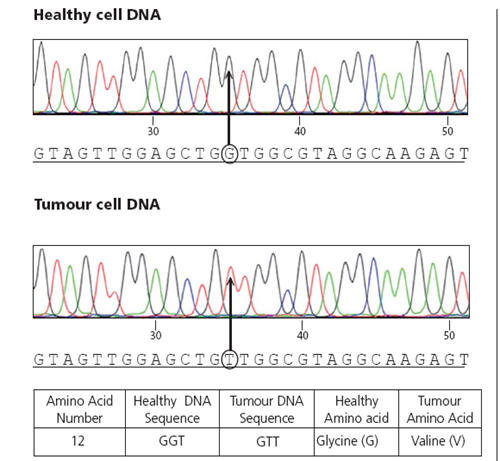

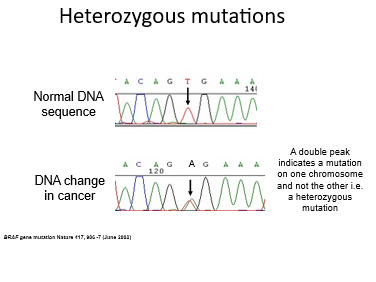

Identifying mutations using sequencing

Each colour represents a nucleotide, can compare healthy DNA to mutated DNA

Can then figure out which amino acids in the proteins will be changed

For example at position 12 a glycine is changed to a valine, which will lock the Ras into the GTP format due to a higher affinity –L> doesn’t require upstream signalling for activation

Called a G12V mutation as its G—>V at position 12

Heterozyous muations

As we have two copies of the genes, we can have a mutated gene and a normal one which looks like this: representing a normal and mutated allele

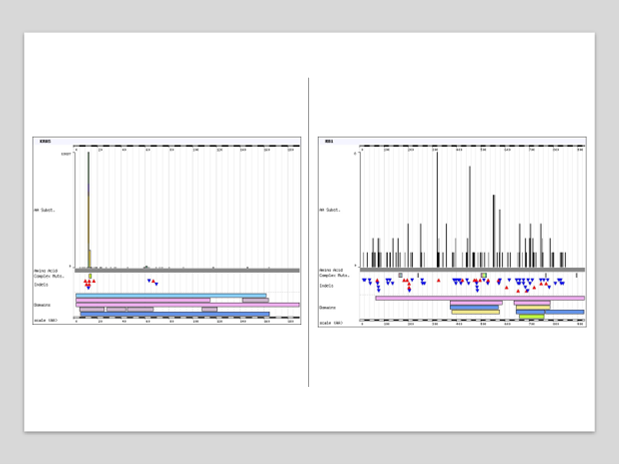

How common are Kras mutations

There are specific hotspot mutations which are more common

These are in position 12, 13 and 61

The particular mutations will create a unique binding site in the tumour KRAS which we can target

Therefore, the wild-type Ras will be unaffected —>selectivity

Impact of Kras mutations

Growth signals, released when cells are damaged stimulate Kras

Kras activity is important for the proliferation of cells when they’re damaged

Ras has GAP, an enzyme which can inactivate it by exchanging GTP for GDP

Comparison of Kras and RB1 tumour supressor gene

Mutations in the RB1 (tumour supressor) are a lot more evenly dispersed, don’t necessarily have specific hotspots

Also deletion mutations a lot more common in the tumour suppressor genes

On the right is RB1 and left is Kras mutations

For the tumour suppressor genes, as long as there is a loss of function of the tumour suppressor gene, it will be inactive. However, mutations in the oncogene must be more specific as it must affect the GTP binding site.

Carcinogens

Introduce mutations to key genes

Can activate oncogenes

Herb treatments

Some can be carcinogens

Unique mutation patterns in Asian cohorts linked to carcinogens in herbal medicines

UV light

Linked to malignant melanoma

Signature C—>T or G—>A mutations

If these DNA changes occur in critical genes like BRAF this can lead to inappropriate cell growth and melanoma

Tobacco smoke

Tobacco smoke carcinogens such as PAH (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons)

Signature G—>T mutations

HPV

Linked to cervical cancer

The most high risk (HPV16) the viral protein can activate oncogenes and cause inactivation of tumour suppressor genes

Eg: E6 viral protein produced by HPV virus can promote degradation of p53

Oncoproteins integrated into the cells

Now a vaccine to reduce cases of cervical cancer

Diet and obesity

Linked to bowel and stomach cancer

Inflammation from the diet linked to damage to the cells lining the stomach/bowel

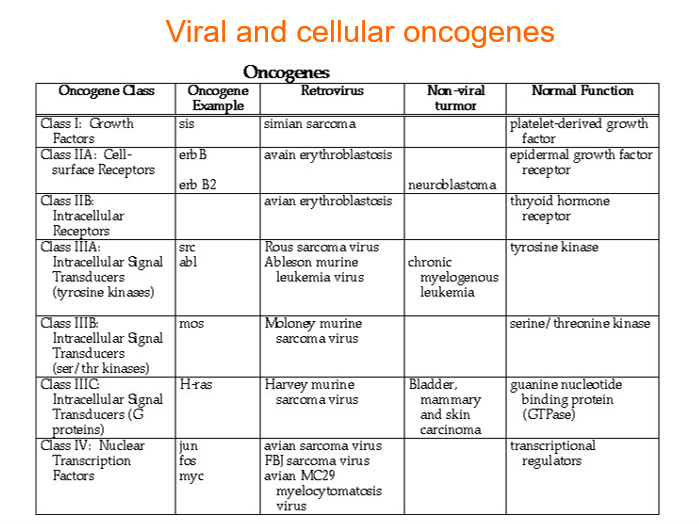

Viral and cellular oncogenes

Viral and cellular oncogenes

Some cancers linked to viruses, were previously thought that it was caused by the oncoproteins from the virus causing cancer

Cellular oncogene will only be activated when necessary but when infected with viral infection the virus controls the expression of oncogene —> may cause loss of function of overexpression

some viruses can also cause cancer due to the chronic inflammation which leads to increased ROS which damages cells and induces mutations

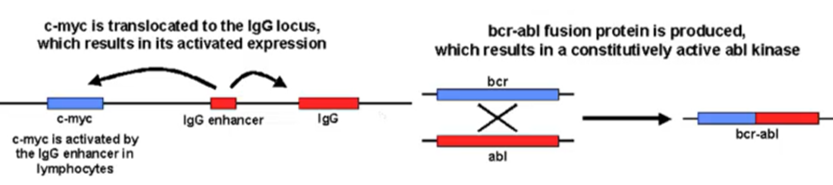

Translocation - Example C-Myc

CMyc an important oncogene which is controlled by its own promoter

Will only be expressed when it needs to proliferate

A single translocation event can cause Myc to be under control of IgG promoter rather than its own promoter

IgG more regularly produced than Myc

Targeting cancers

Loss of tumour suppressors gives cancer cells growth advantages:

Sustaining proliferative signals

Evading growth suppressors

Depending on which molecules provide these advantageous signals, we can create selective targets

Very challenging for us to restore tumour suppressor functions, as there are often more mutations in the tumour suppressor gene and you don’t know which mutation is causing loss of function

Oncogenes are good targets as they often have mutation hotspots —> relatively easy to design a drug to stop oncogene signalling

These targets can be applied for different types of cancer —> targeting based off the driving mutation not location

Specific examples of gene mutations

BCR-ABL

EGFR

BRAF

PD-1/PDPL-1

VEGF

Precision medicine

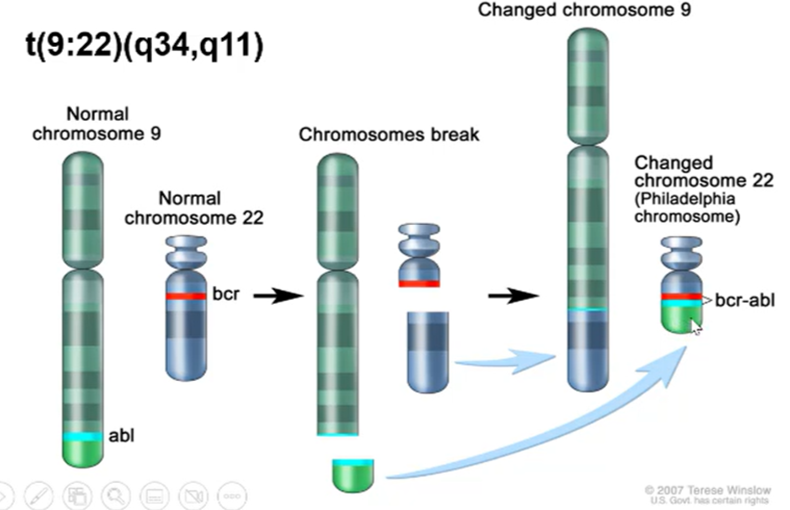

BCR-ABL oncogene

Results in a Philadelphia chromosome eliciting a fused protein

BCR gene is usually present in the q11 region of chromosome 22, ABL gene usually present on q34 region of chromosome 9

This translocation is written as t(9:22)(q34,q11)

T before brackets indicates a translocation

Q indicated that the mutation is on the long arm, p indicated the short arm

forms a fused protein which drives chronic myeloid leukaemia in all cases and acute lymphocytic leukaemia in 10% of cases

When you have the fused protein present there’s a coiled-coil domain which is always dimerised, leading to constant activation of the cell cycle

The wild type proteins are essential for the normal function in the cell but the difference is that signalling is only activated when required.

Most effective drugs against this mutation is the tyrosine kinase inhibitors —> this inhibits the ABL protein allowing for selective destruction of the cancer cell

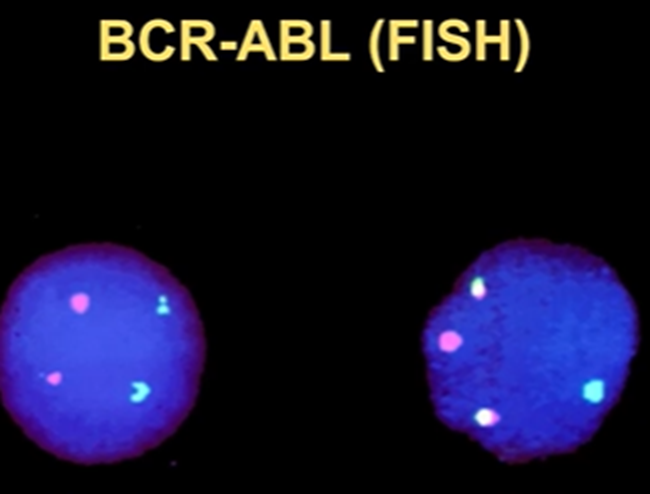

Visualisation of fused proteins using FISH

These fused proteins can be visualised by FISH (fluorescent in situ hybridisation)

The green tag indicated the ABL protein, and the red indicates the BCR

In the normal situation, the two colours are distinct, but when there’s a translocation, the colours are mixed

Useful for diagnosis/ identifying mutation occurring in the cancer

Targeting these proteins

Imatinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Any drugs which end in -ib means it’s a small molecule inhibitor

Holds the activation loop in the inactive conformation which stops signalling of both w/t and cancerous ABL

Kinases are relatively easy to inhibit so tend to be most successful anticancer agents

Mutations and persistence of cancer

However, cancer cells have an unstable genome so can relatively easily acquire mutations

If a mutation occurs in the binding site for the imatinib, then this drug is no longer effective, and the cancer will persist

After a few rounds of treatment around 1/3 of patients will develop a mutation. Common mutations which change the structure include: T315I (most common), E255K, H396P

Other mechanisms of resistance include

Use of an alternative pathway to create the survival signals

Use a different mechanism to activate downstream events

Amplify the ABL to overcome the inhibition

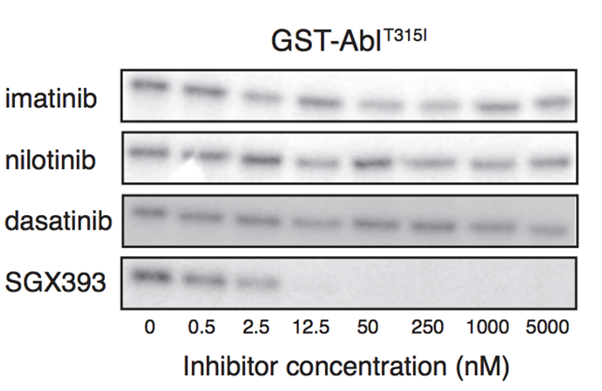

2nd generation drugs

Bind more tightly to the binding site

Can't cope with the T315I mutation —> both 1st and 2nd generation are not successful at all

All of them successfully bind to wild-type ABL

Examples: Dasatinib, nilotinib

3rd generation

SGX393 a 3rd Gen BRC-ABL inhibitor

We can see from Western blots that this is the only drug which can inhibit mutant T315I

Since this is the only drug which works against this specific mutation, it’s essential to know which kind of mutation is causing the patients cancer.

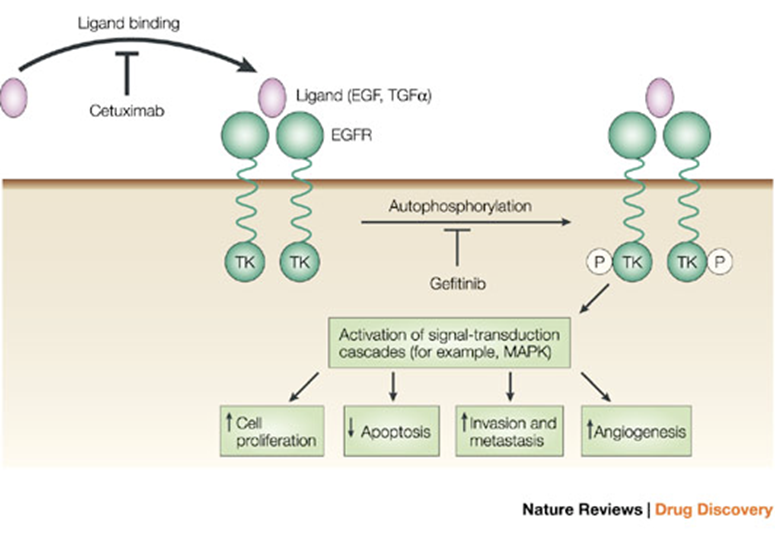

EGFR as target

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

Important signal for tissue repair and wound healing

Controlled by ligand binding to the receptor, causing a dimerisation which activates the Ras signalling pathway (which goes onto activate Raf and Erg)

Unlike BCR-ABL, EGFR mutation is mainly driven by point mutations

Illicits lung cancer

Cetuximab prevents the ligand from binding to EGFR, however, this will not work in cancer types where the mutation is in the EGFR causing it to be constantly dimerised

Useful in cancers which are caused by amplification of ligand (EGF) or overexpression of the receptor

Gefitinib is another drug which binds to the centre of EGFR to prevent the signalling —> successful in cancers which are caused by mutations in EGFR which result in constant dimerisation

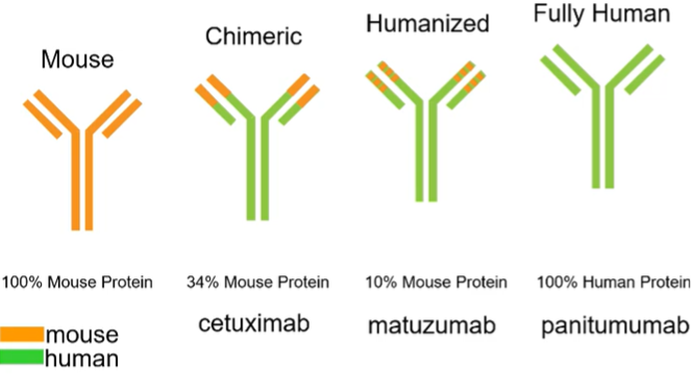

Monoclonal antibodies as targeted therapy

Can be used in some cases E.g: EGFR

Need to humanise the antibodies so they’re more stable

However, again, when we tray and treat the mutation the cancer will try to develop other mechanisms to overcome this

T790M mutation accounts for 55% of mutations resulting in the re-establishment of this pathway.

Other mechanisms to re-establish this pathway

BRAF: Overexpression of Raf (downstream)

MAPK1: downstream of the Ras

PI3K: downstream of EGFR

MET: upstream of the Ras pathway

HER2: mechanism to activate Ras signalling pathway (upstream)

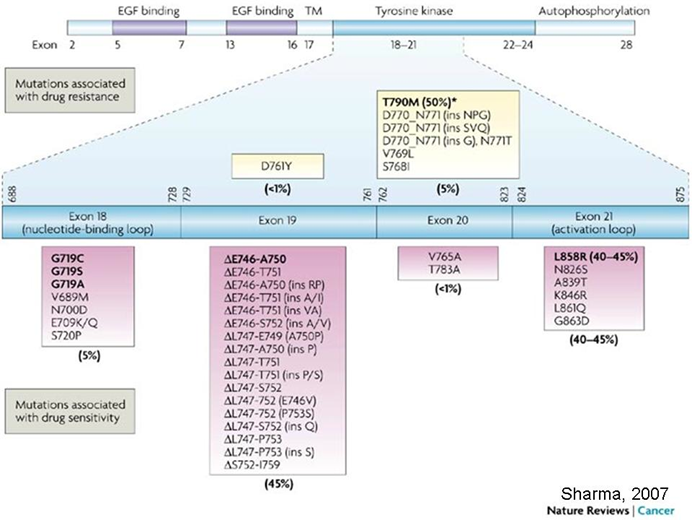

EGFR mutations

Big protein, mutations frequently occurring in exons 18,19, 20,21

examining where the mutation lies is important for determination of treatment —> sequencing of EGFR necessary for this

Below the diagram is the index of mutations associated with drug sensitivity so can give anti-EGFR treatment

L858R mutation In exon 21 is an activation mutation

Above the diagram is the index of drug resistance mutations, which usually happens after several cycles of treatment.

T790M mutation is a drug resistance mutation

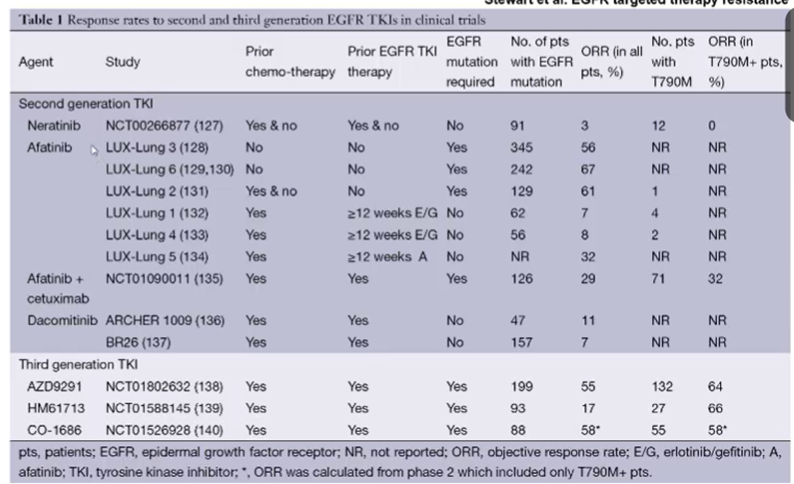

How can we treat patients with resistance induced by first gen treatments?

In EGFR mutations causing cancer L858R and E746-A750 mutations are oncogene activation mutations while T790M is a resistance mutations

First-generation treatment causes this mutation to arise, second generatuion drugs such as Afatinib and Neratinib are also ineffective against this type of cancer.

Typically second generation EGFR TKIs form irreversible covalent binds with the ATP binding site of EGFR as well as other members of the HER family of receptors

Third-generation drugs on the other hand, such as AZD99291, HM61713 and Co-1686 will be effective in approximately half of cases.

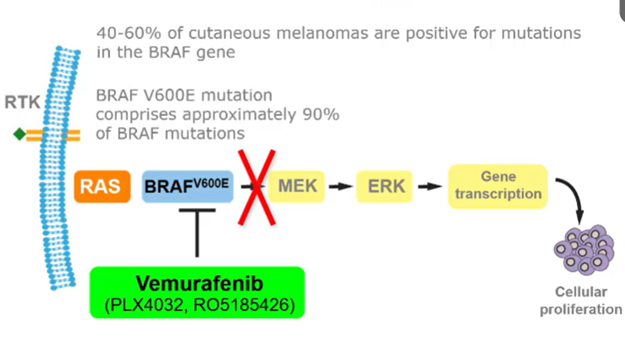

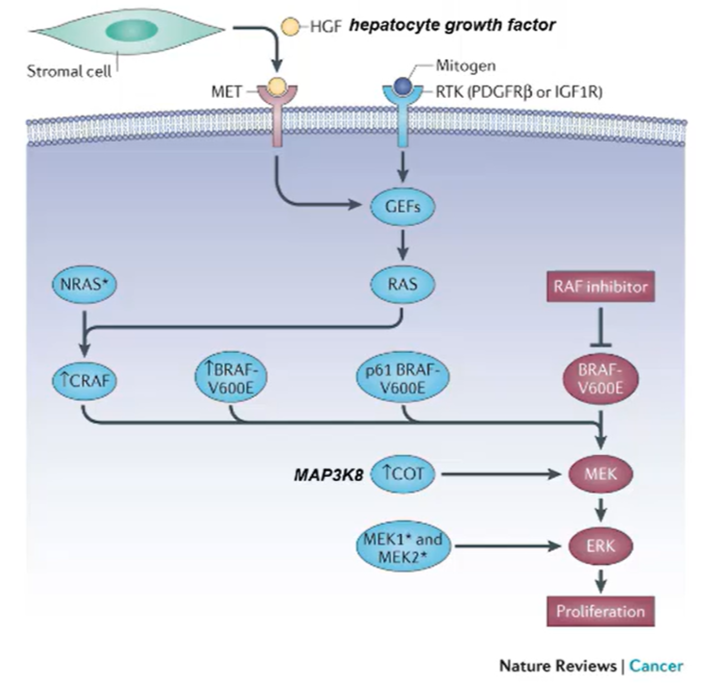

Vermurafenib

Small inhibitor targeting BRAF V600E mutation

Can no longer activate the MEK/ERK pathway

However, the cancer cells can reestablish the ERK surviving signals by:

mutations in MEK1 and MEK2

Upregulation of genes that can activate MEK

Overexpress another isoform of BRAF

Increase the expression of another RAF called CRAF

Introduce mutations in RAF genes/other upstream events

Once we understand these alternative mechanisms we can come up with another drug to treat them

Unlikely that we can treat the cancer completely but can keep the cancer at a low level, so is less of a burden to the patient —> cancer now considered a chronic disease

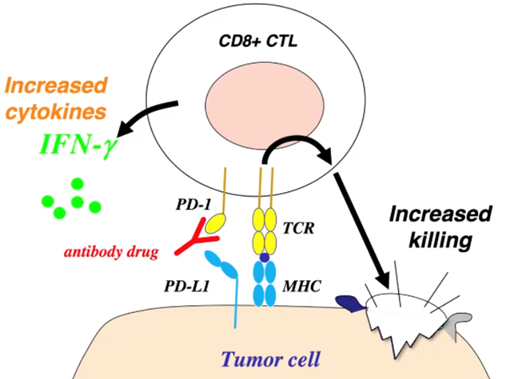

Immunotherapy

2 major checkpoints in our body

CTLA-4 in the lymph node

PD-1 in the tumour

These two signals act as surviving signals for cells and confer protection against the immune system

This interaction between PD-1 on the T cells and PDL-1 on the tumour cells dampens the immune response and protects the tumour against the immune system

However, we can create anti PD-1 antibodies to block this signal and selectively kill the tumour cells.

Healthy cells are spared from this because their surface antigens are not recognised by the immune system, although this is not entirely selective

Anti-PD01 treatment shown better efficacy than the chemotherapeutics.

VEGFR

Tumour outgrowths creates a hypoxic environment which triggers the expression of VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) which will stimulate the creation of new blood vessels to supply nutrients and oxygen

VEGF antibodies removes the nutrient supply to the new cancer cells

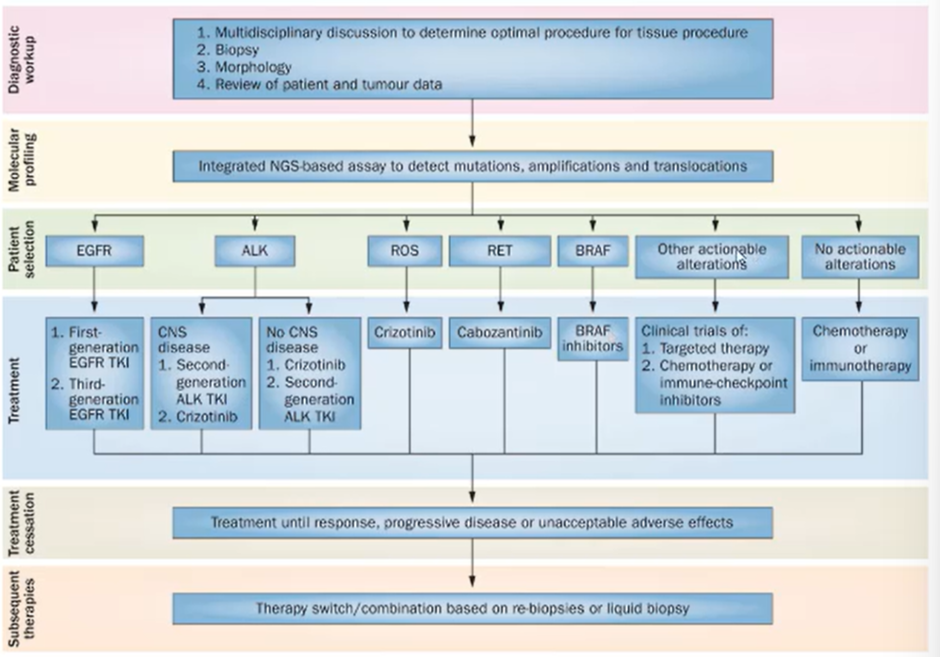

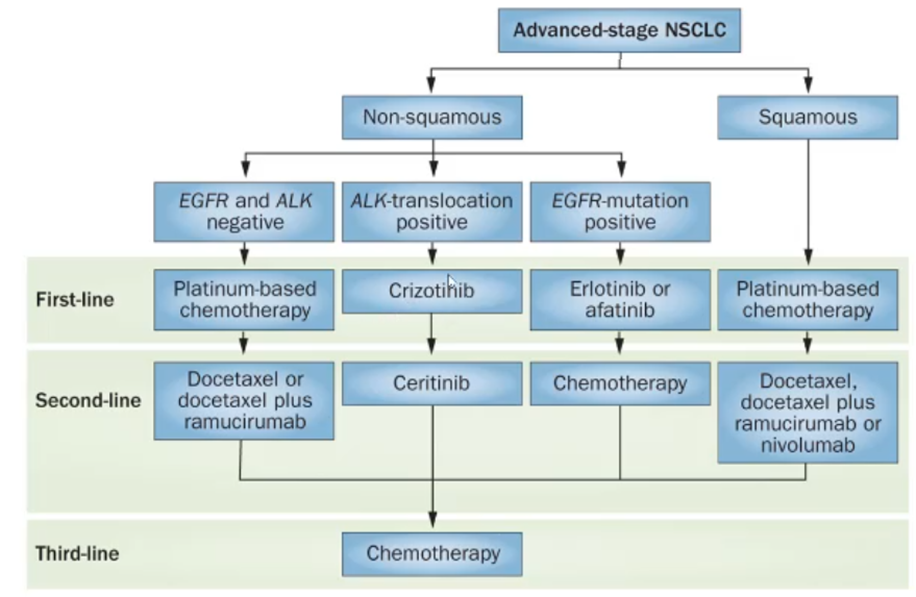

Precision medicine

Treating the patient based off the driving mutation

When we first diagnose the patient with cancer must decide if their cancer is squamous or non-squamous

In most cases squamous wont have a driving mutation and so will have to use traditional cytotoxic or chemotherapeutics

If the patient has a non-squamous cancer, such as EGFR mutation, can give erlotinib or afatinib —> if unsuccessful can use chemotherapy

If the patient has ALK translocation we give them crizotinib and if that doesn’t work certinib

If the patient is EGFR and ALK negative give them platinum based chemotherapeutics.

Potential algorithm for incorporating chemotherapies, immunotherapy and targeted therapies