Mod 5 (Ch 4) - Coping with Environmental Variation: Temperature and Water

1/70

Earn XP

Description and Tags

included on exam 1

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

71 Terms

examples of abiotic (physical) factors that constrain the geographic range of species

climate

water

disturbance (e.g. fire, temperature, water)

examples of biotic (biological) factors that constrain the geographic range of species

interactions with other organisms

food availability

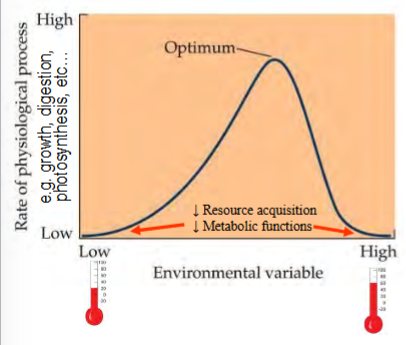

results of suboptimal conditions

suboptimal conditions → physiological stress → suboptimal physiological performance → reduced survival, growth, or reproduction

physiological stress

suboptimal physiological performance that results from suboptimal conditions

decreased resource acquisition, decreased metabolic functions

(not the same as psychological stress)

i.e. you might have to divert extra energy to adjusting for suboptimal conditions, you might be uncomfortable, etc.

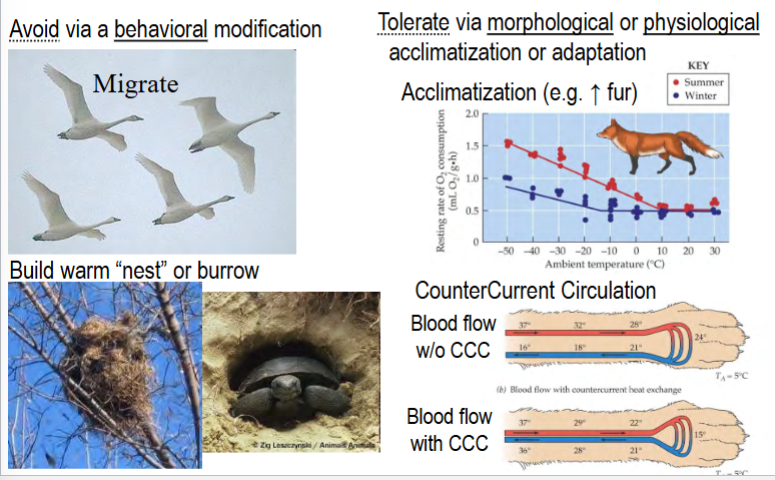

3 options for reaction to physiological stress

avoidance

tolerance

death

avoidance

one option in response to physiological stress

lessens effects of stress via behavioral/physiological activity that minimizes exposure to the stress

typically a behavioral response (e.g. basking in the sun, adjusting activity times, migrating, seeking shelter)

tolerance

one option in response to physiological stress

the ability to survive physiologically stressful abiotic conditions

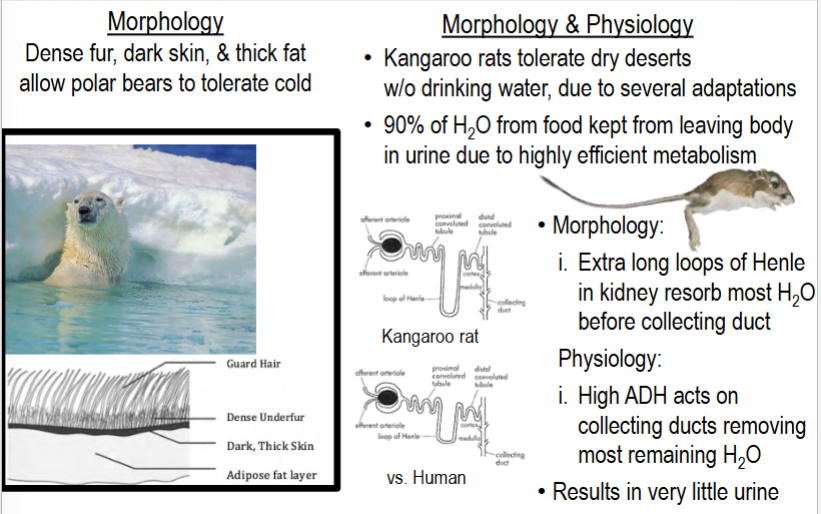

typically via morphological or physiological adaptation (e.g. skin and fur of polar bears, nephrons of kangaroo rats; understand these examples)

range of tolerances

the extremes to which a species can tolerate varying abiotic factors (e.g. how hot and how cold, or how wet and how dry)

influences potential distribution and abundance of that species

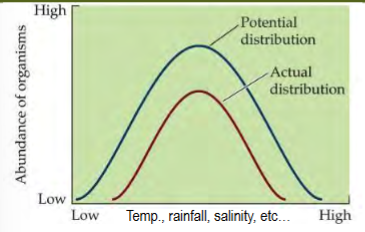

actual species distribution vs potential distribution

actual distribution is usually narrow than potential distribution

due to extreme climatic conditions, disturbance, species interactions

(e.g. most individuals might not be able to handle the extremes, thus species distribution will not extend into those extreme potential areas)

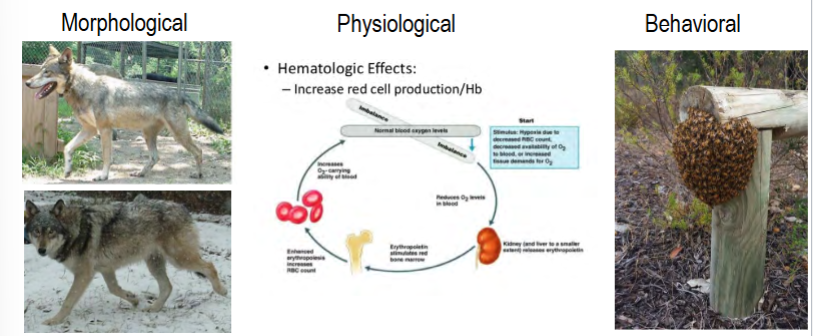

how adaptations are produced

natural selection acts on individual phenotypes → chooses traits that allow avoidance or tolerance of suboptimal conditions (reduce physiological stress)

adaptations can be behavioral, morphological, or physiological, because natural selection acts on those three things

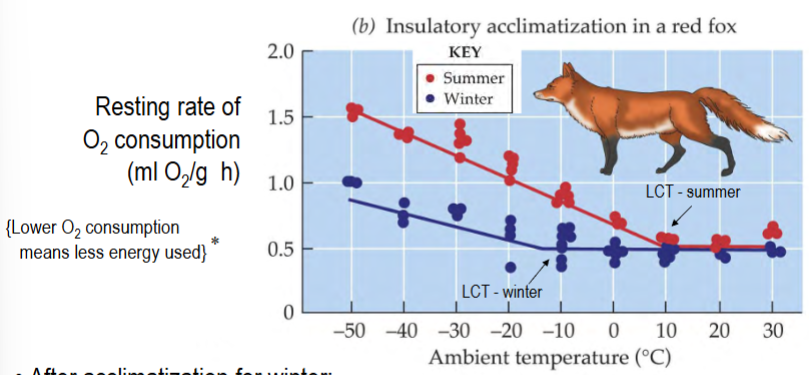

acclimatization

relatively rapid, temporary phenotypic change in individuals to reduce effects of physiological stress

individual (NOT entire species) response to abiotic variation

occurs over a relatively short time period

can and will reverse if the stress is eliminated

can be morphological, physiological, or behavioral adjustment

does not eliminate physiological stress

amount is limited by the level of phenotypic plasticity

e.g. growing thicker fur in winter, increasing erythrocyte production, bees forming a ball to keep warm

adaptation

genetic change in the entire population

population (NOT individual) response to abiotic variation

natural selection for particular phenotypes that increase survival/reproduction

may be morphological, physiological, and/or behavioral

can allow later generations of a population to return to pre-stress levels (even if the stress does not go away, adaptation makes the population better able to handle the stressor with a lower level of physiological stress)

sometimes irreversible, sometimes reversible (but takes several generations)

e.g. over time, in colder environment, population size increases and shows more countercurrent circulation and tendency to bask in the sun

e.g. the ability to acclimatize (not the act of acclimatization itself)

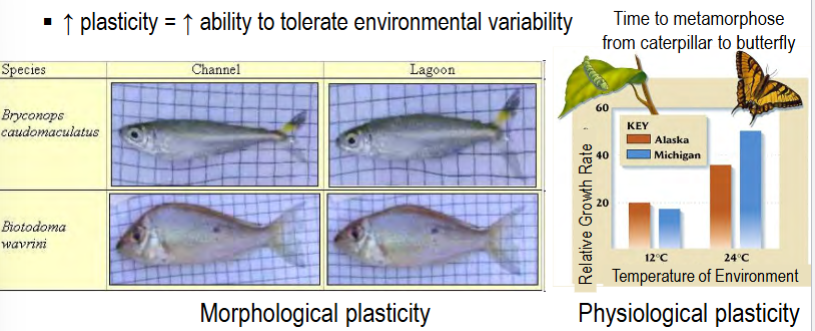

phenotypic plasticity

the range of phenotypes that can be displayed by a genotype in response to environmental variation

i.e. flexibility in response to environmental change

varies between individuals, populations, and species

direct correlation with ability to tolerate environmental variability

e.g. ability to change body shape based on living conditions when young, time to metamorphose

similarities between acclimatization and adaptation

reduce stress; morphological, physiological, and/or behavioral

increase survival probability and/or reproductive output

relatively long-term/permanent in contrast to an acute response

differences between acclimatization and adaptation

type of change (phenotypic vs genotypic)

scale of change (individual vs population)

speed of response (rapid vs over generations)

reversibility

(see the chart on slide 13, know specifics of differences)

trade-off between acclimatization and growth

energy used for acclimatization means less energy available for growth/survival/reproduction

only populations in variable environments (who would need to acclimatize) evolve the ability to acclimatize

populations in constant environments do not evolve the ability to acclimatize

correlation between phenotypic plasticity and environmental conditions

ability to acclimatize and level of phenotypic plasticity reflects range of conditions naturally experienced

(greater variation between conditions results in greater plasticity and ability to acclimatize)

^due to the energy trade-off of acclimatization and growth

distinction between acute response, acclimatization, and adaptation

acute response is a response, immediate and short-term

acclimatization is the adjustment of a response within an individual, i.e. an acute response happens differently

adaptation is the long-term adjustment of an acclimatized trait; e.g. the ability to acclimatize or show an acute response

(see the sweat example on slide 20)

how temperature affects physiological activity

changes the rate or occurrence of chemical reactions

affects cell membranes

increases water loss

how temperature affects rate or occurrence of chemical areactions

directly

indirectly: altering enzyme activity or denaturing enzymes

how temperature affects cell membranes

cell membranes lose function at lower temperatures

membranes leak → lose their filtering function

transport proteins lose function → affect mitochondrial, chloroplast, and other processes

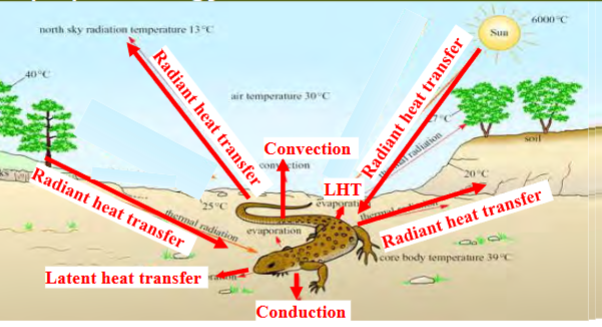

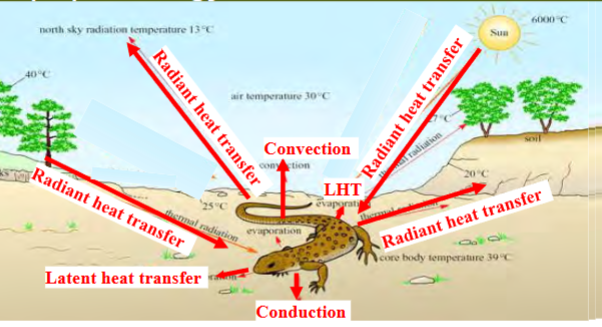

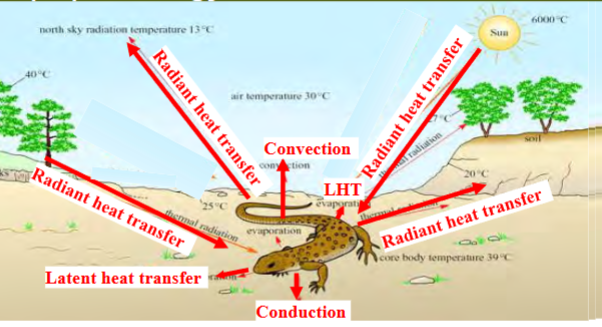

how temperature of an organism is determined

by exchanges of energy with the external environment (gain or loss)

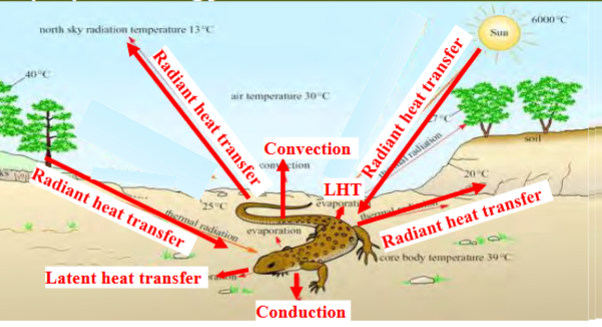

4 mechanisms of heat transfer

conduction

convection

latent heat transfer

radiant heat transfer

conduction

one mechanism of heat transfer

transfer of heat via direct contact of molecules

e.g. between a warm hand and a cold table

convection

one mechanism of heat transfer

conduction + fluid/gas flow

e.g. baking within an oven

latent heat transfer

one mechanism of heat transfer

heat loss from evaporation or evapotranspiration (liquid → gas)

e.g. sweating

radiant heat transfer

one mechanism of heat transfer

movement of heat via electromagnetic waves (solar + thermal)

e.g. warming beside a fire or the sun, infrared cameras detecting an animal’s body heat

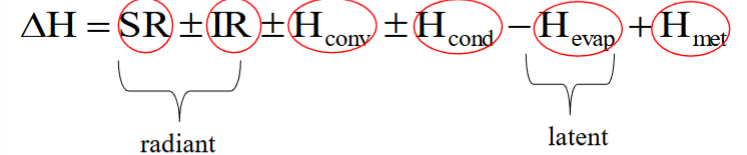

overall temperature change

heat from solar radiation is always gained

heat from infrared radiation can be gained or lost

heat from convection can be gained or lost

heat from conduction can be gained or lost

latent heat from evaporation is always lost

heat from metabolism is always gained

(see the picture for equation)

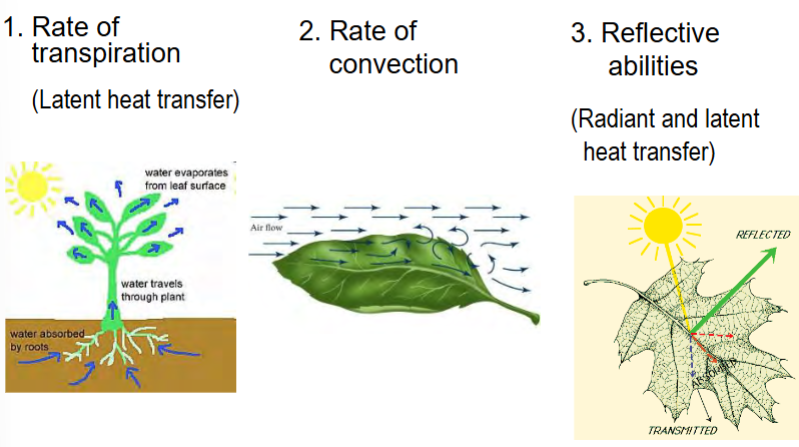

rates at which plants lose/gain heat

depends on morphological physiological attributes that affect their rate of transpiration, rate of convection, and reflective abilities

morphological/physiological attributes affecting rate of transpiration

number of stomata

degree of stomatal opening

cuticle thickness

leaf orientation

leaf closure

transpiration

water uptake + evaporation

can be used to lower temperature

not good in dry areas, where new water is not readily available to replenish lost water

some plants drop their leaves to avoid excess transpiration → use other methods to control body temperature

boundary layer

nonmoving air around a leaf

thicker boundary layer = less air movement = convective heat loss

affected by size, shape, texture, orientation leaves toward/away from wind or sun

how some plants reduce convective heat loss in cold weather

some plants grow low to the ground

some plants develop pubescence

light reflective properties affecting rate of radiant and latent heat transfer

pubescence increases reflected sunlight → lowers heat gain due to radiant heat transfer (keeps the plant cooler)

positive and negative effects of pubescence

benefit: can keep plant warmer or cooler, depending

solar radiation for photosynthesis is lost

convective cooling is less effective

resuls:

summer-acclimatized plants have increased pubescence

pubescence is less common in climates/seasons that are wet or have less sunlight

temperature regulation in animals

regulation depends on where heat comes from (ectotherm vs endotherm) and how body temperature varies (poikilotherm vs homeotherm)

ectotherm

an animal in which body heat is derived from the environment

can augment costs behaviorally or via morphological/physiological changes (i.e. can keep animal warm without needing to use energy) (e.g. basking, turning dark during the day and light at night)

e.g. most reptiles

cost of being ectothermic

activity is limited when cold

many enzymes and physiological adaptations are needed to function at varying temps (these enzymes and adaptations require energy to produce)

endotherm

an animal in which body heat is derived from its own metabolism

e.g. birds, mammals

poikilotherm

an animal in which body heat varies with ambient temperature

homeotherm

an animal in which body heat remains constant

e.g. humans

animals that are poikilothermic ectotherms

most microorganisms, invertebrates, cartilaginous and bony fish, amphibians, reptiles

(if outside temp gets hot, the animal gets hot)

(most '“cold-blooded” animals)

animals that are poikilothermic endotherms

many subterranean rodents (have limited O2 and heat, maintain low BMR and body temperature near ambient)

animals that are homeothermic ectotherms

many smaller oceanic fish in stable temperatures (functionally homeothermic)

animals that are homeothermic endotherms

most birds and mammals

heterotherm

an animal that is poikilothermic and homeothermic

usually these animals are most often homeothermic and sometimes poikilothermic

animals that are heterothermic ectotherms

many bees, moths, some reptiles (they shiver sometimes)

some large fish use countercurrent circulation in some muscles

some plants increase respiration (thus heat) in late winter

animals that are heterothermic endotherms

mammals and birds (poikilothermic during torper or hibernation)

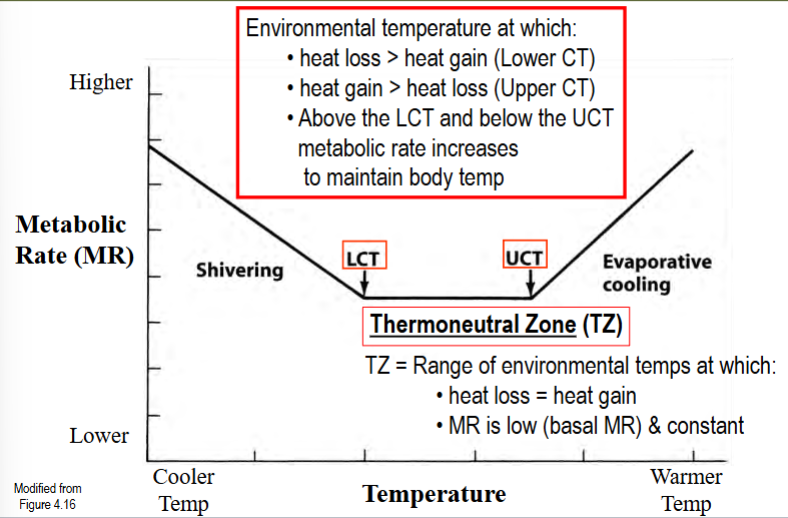

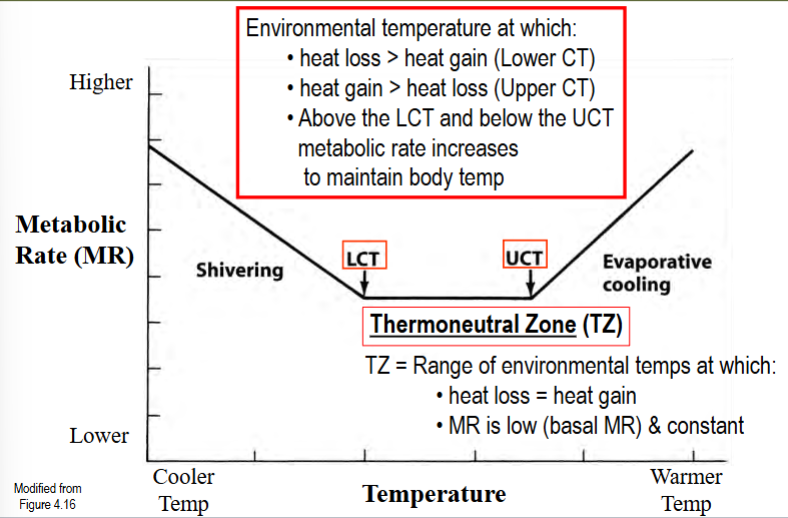

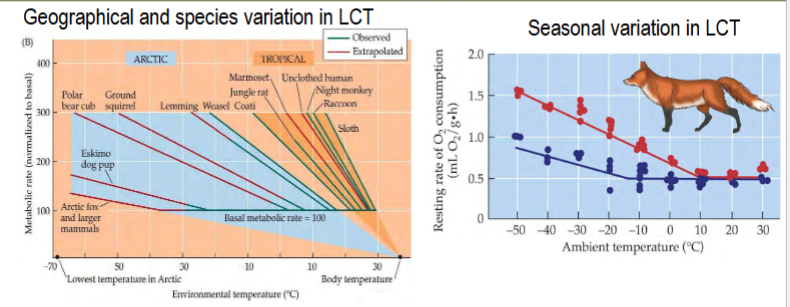

critical temperatures (lower and upper)

environmental temperatures at which an endotherm’s metabolic rate has to increase to maintain body temperature

heat loss =/= heat gain

in between these temperatures is the thermoneutral zone

for lower CT: heat loss > heat gain (shivering occurs)

for upper CT: heat gain > heat loss (sweating occurs)

thermoneutral zone

the range of environmental temps at which an endotherm’s metabolic rate is low (basal) and constant

heat loss = heat gain

in between the upper and lower critical temps

how acclimatization changes acute response

by lowering upper or critical temperature → less energy consumption

e.g. by growing thicker fur or bulking for winter, energy consumption is reduced and increased energy isn’t needed until colder temperatures

how lower critical temp for animals varies

varies geographically, seasonally, and among species, depending on energy needs and food availability

lower LCT → wider TNZ → less energy used

lower in animals with higher energy demands or less access to food (to conserve energy)

what happens to animals that can’t sufficiently augment heat loss?

if animals can’t increase their metabolic rate to augment heat loss: they must avoid or tolerate conditions, or die

i.e. by behavioral modification or morphological/physiological acclimatization/adaptation

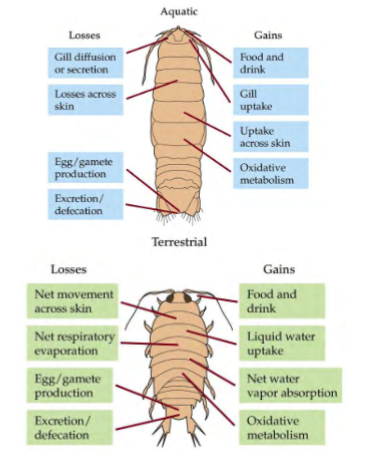

osmoregulation

balance of uptake and loss of water and solutes to regulate body fluid composition and pH

affected by exchanges with external environment

differences in water uptake/loss in aquatic vs terrestrial animals

aquatic animals gain water through: food and drink, gill uptake, uptake through skin, oxidative metabolism

terrestrial animals gain water through: food and drink, liquid water uptake, net water vapor absorption, oxidative metabolism

aquatic animals lose water through: gill diffusion/secretion, losses across skin, egg/gamete production, excretion/defecation

terrestrial animals lose water through: net movement across skin, net respiratory evaporation, egg/gamete production, excretion/defecation

(note: the main differences are in absorption/loss across skin and gills)

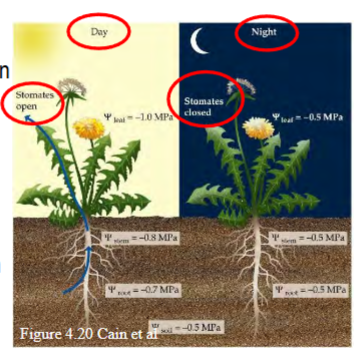

how plants osmoregulate in water-stressed environments

they regulate when their stomata are open (daytime) and closed (nighttime)

daytime: dehydration

stomata open to let CO2 in and O2 out

evaporative water loss > uptake through roots (except in very humid air)

nighttime: rehydration

stomata mostly close

evaporation slows → water loss < uptake through roots

acclimatizations for plants to minimize water loss and maximize water gains in dry environments

adjustment of cell wall and cuticle thickness (reduces water loss)

shedding of leaves in dry periods (reduces water loss, requires less nutrients)

adjustment of root biomass to optimize water uptake (maximize water gains; dryer environment → greater root mass)

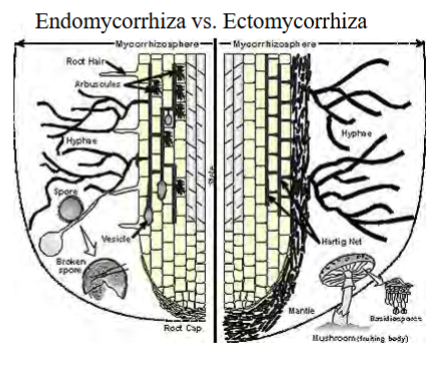

mycorrhizal fungi

symbiotic fungi that attach to plant roots (myco = mushroom/fungus, rhiz- = root/rhizome)

affect water balance in plants

large surface area of fungi increases water absorption for plants

fungi take some food from plants

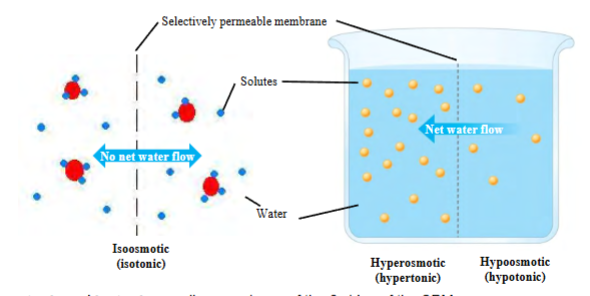

osmosis

the diffusion of water from areas of lower solute concentration to higher solute concentration

(the water moves, not the solutes)

osmoregulation in freshwater vs saltwater fishes

osmosis creates imbalance

drinking, eating, excretion, and active transport compensate for these gains/losses

saltwater fish are hypotonic to their environment; gain water from food and drinking seawater; excrete salt from gills (active transport), lose water through gills and body surfaces, excrete excess salt and a little bit of water

freshwater fish are hypertonic to their environment; gain water and ions in food, uptake slat by gills, uptake water through gills and body surfaces; diffuse salt from gills, excrete lots of water and some ions

how amphibians avoid water loss through their thin skin

live in moist environment

increase skin thickness (must breath faster to compensate for reduced oxygen intake)

have highly vascularized and/or bumpy ventral (stomach) skin to increase water absorption

have thick and bumpy dorsal skin to reduce convective water loss (toads (terrestrial frogs))

how reptiles avoid water loss

shedding (increases thickness of all skin layers, especially the outermost)

have scales to provide protection and reduce water loss

excrete dry solid urine

shells are leathery/hard (resist drying) and have storage areas for wastes

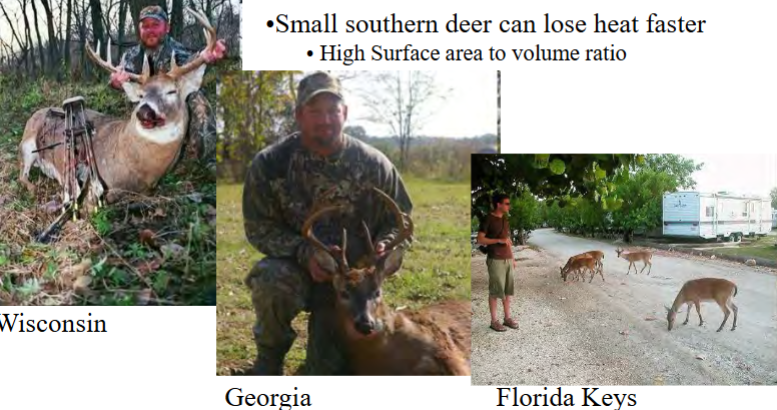

surface area:volume ratio and rate of heat/water gain/loss

small animals have a higher SA:V ratio than large animals → more prone to water loss and rapid temperature shifts

SA:V ratio also affected by body shape and appendages

elongated animals and elongated appendages → higher SA:V ratio

ectothermic dinosuars: probable or improbable?

improbable

because of low SA:V ratio

Bergmann’s rule

body mass increases with latitude and colder climate

larger animals retain heat better than small animals

e.g. deer; much larger in Wisconsin than Florida

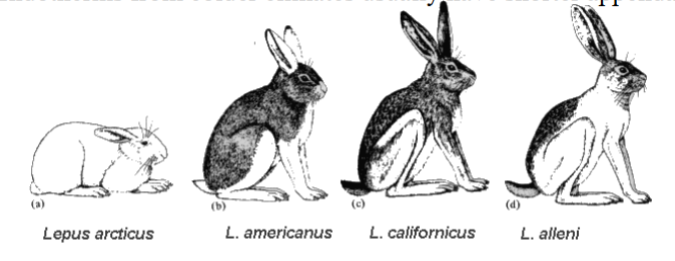

Allen’s rule

endotherms from colder climates usually have shorter appendages

e.g. jackrabbits vs arctic hares, see their leg lengths

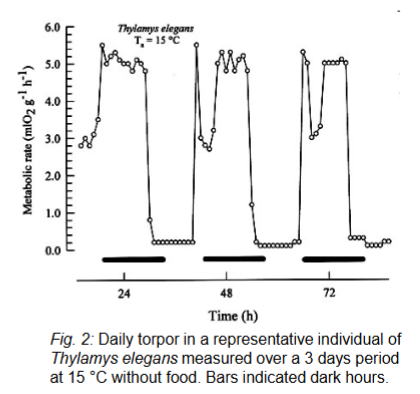

torpor

a reduced state of activity and metabolic rate, below basal metabolic rate (BMR)

may occur over short or long periods of time

daily torpor

a short-term torpor that occurs in many bats, small mammals, birds

small mammals can lower body temp to near freezing, but wake up every days to eat and excrete

hibernation

a type of long-term torpor

a response to cold and food scarcity

e.g. bears can hibernate for 7 ½ months without waking up

aestivation

a type of long-term torpor

response to heat and water scarcity

e.g. in lungfish, caiman, early proto-amphibians

some cold-tolerating acclimatizations/adaptations

frozen frogs

torpor