Dementia (Alzheimer's disease)

1/39

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

40 Terms

Dementia – a public health crisis

One of the major causes of disability and dependency among older people.

In Singapore, 1 in 10 seniors above the age of 60 years old has dementia according to the WiSE study reported in 2015.

About 28,000 people aged 60 years and above live with dementia.

By 2030, there will be over 150,000 persons with dementia

AD - Pathophysiology

AD is associated with brain shrinkage and loss of neurons in many brain regions, but especially in the hippocampus and basal forebrain

Main pathological features of AD comprise

1) Amyloid plaques

2) Neurofibrillary tangles

3) Loss of neurons (particularly cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain) → thought to underlie the cognitive deficit and loss of short -term memory

AD - Amyloid plaques & neurofibrillary tangles

Amyloid plaques : Aggregates of the Aβ fragment of amyloid precursor protein (APP), a normal neuronal membrane protein, produced by the action of secretases α, β and γ

Neurofibrillary tangles : Comprise intracellular aggregates of a highly phosphorylated form of Tau, a normal constituent of neurons associated with the intracellular microtubules that serve as tracks for transporting materials along nerve axons

Hyperphosphorylated Tau and Aβ act synergistically to cause neurodegeneration

Mechanisms may include direct impairment of synaptic transmission and plasticity, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation

AD - loss of neurons

Discovery in 1976 from post-mortem of AD brain tissues saw a relatively selective loss of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain nuclei

The “cholinergic hypothesis” was formulated based on observation of deficiency of ACh in AD and that centrally-acting cholinergic antagonist (atropine) induced confusional-state resembling dementia

Implied that pharmacological approaches to restoring cholinergic function might be feasible

AD, however, is complex and also involves multiple neurotransmitter systems, including glutamate, 5-HT, and neuropeptides

There is destruction not only of cholinergic neurons but also of cortical and hippocampal targets that receive cholinergic input

AD - diagnosis

DSM-5: Neurocognitive Disorders

Diagnosis is made in two steps:

1. Syndrome:

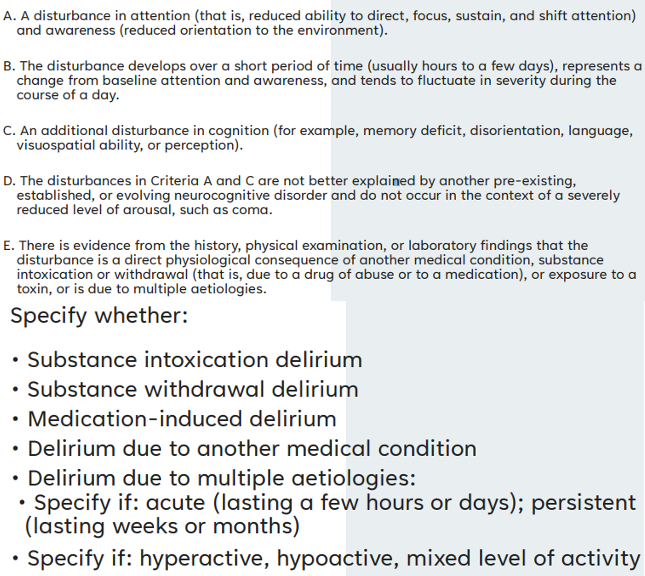

Delirium

Minor cognitive impairment

Major cognitive impairment (dementia)

2. Etiology

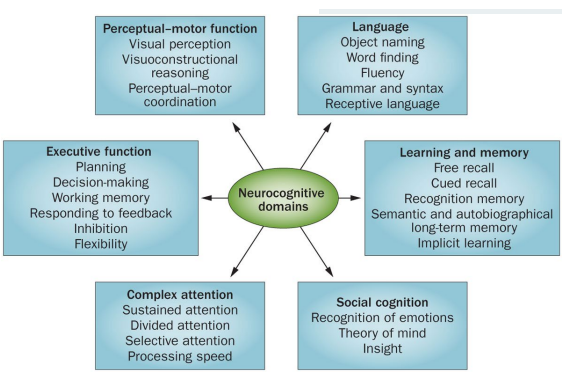

DSM-5 - neurocognitive domains

DSM-5 - delirium

DSM-5 - Minor Neurocognitive Disorder (MCI)

A. Evidence of modest cognitive decline from prior level of performance in one or more cognitive domains (complex attention, executive function, learning & memory, language, perceptual-motor or social cognition

1. Concern of the individual, a knowledgeable informant or the clinician there has been mild decline in cognitive function

2. A modest impairment in cognitive performance preferably documented by standardized neuropsychological testing or in its absence other quantified clinical assessment

B. The cognitive deficits do not interfere with independence in everyday activities

C. The cognitive deficits do not occur exclusively in the context of delirium

D. The cognitive deficits are not better explained by another mental disorder

DSM-5 - Major Neurocognitive Disorder (Dementia)

A. Evidence of significant cognitive decline from prior level of performance in one or more cognitive domains (complex attention, executive function, learning & memory, language, perceptual-motor or social cognition

1. Concern of the individual, a knowledgeable informant or the clinician there has been significant decline in cognitive function

2. A substantial impairment in cognitive performance preferably documented by standardized neuropsychological testing or in its absence other quantified clinical assessment

B. The cognitive deficits interfere with independence in everyday activities

C. The cognitive deficits do not occur exclusively in the context of delirium

D. The cognitive deficits are not better explained by another mental disorder

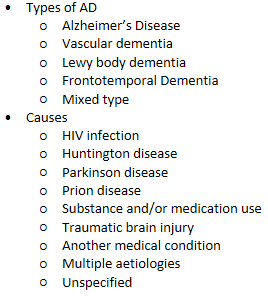

Dementia - etiology

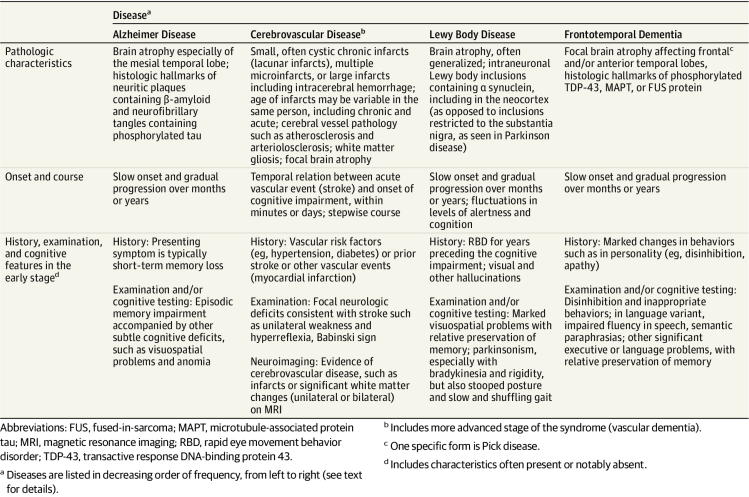

Dementia - Clinical and pathological characteristics of diff types of dementia

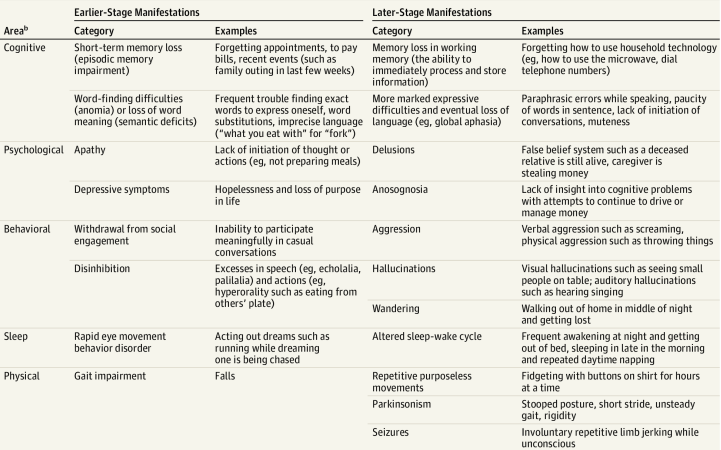

Dementia - manifestations

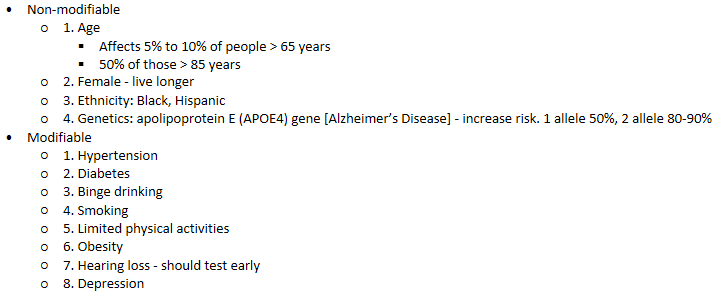

Dementia - Risk factors

Dementia - Anticholinergic use

Negatively impact cognition

Long term use may increase risk of dementia

Review and substitute whenever possible:

Antihistamines [first generation e.g. chlorpheniramine, hydroxyzine, promethazine]

Skeletal muscle relaxant [orphenadrine]

Antispasmodics [e.g. atropine – combi products]

Bladder antimuscarinics [e.g. oxybutynin, tolterodine]

Antidepressants [e.g. amitriptyline, imipramine, paroxetine]

Parkinson’s disease [benzhexol, benztropine]

Antipsychotics [e.g. chlorpromazine,

Assess anticholinergic load and weigh clinical need

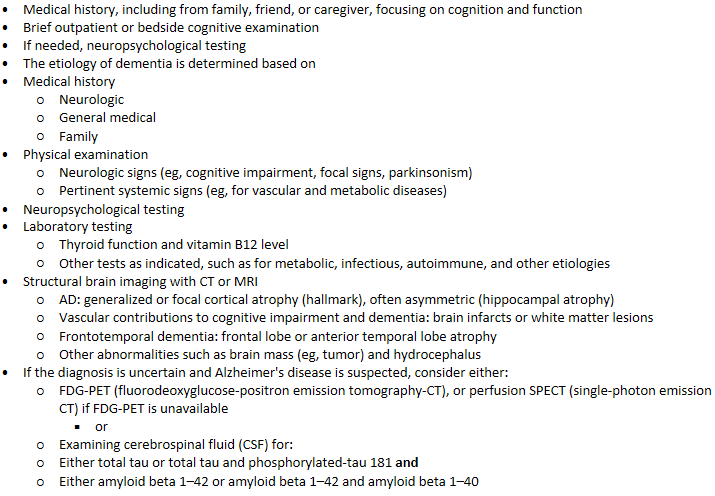

Dementia - Clinical Evaluation of suspected Dementia

Dementia - Brief Cognitive screening Tool

MMSE - pic

MoCA

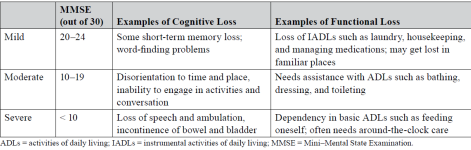

Mild cognitive impairment: 18–25 points

Moderate cognitive impairment: 10–17 points

Severe cognitive impairment: less than 10 points

AD - management

Pharmacologic treatment

Non-pharmacologic approaches

Goals: Reduce suffering caused by the cognitive and accompanying symptoms (eg, in mood and behavior), while delaying progressive cognitive decline

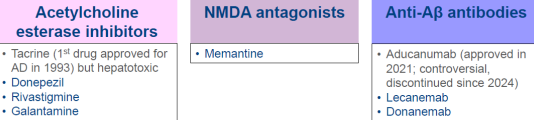

AD management - Anticholinesterase Inhibitors (AI)

MOA

Inhibit acetylcholinesterase enzyme - thereby promoting relative increases in acetylcholine abundance at the synaptic cleft for cholinergic neurotransmission

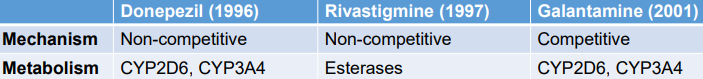

All 3 (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine) are reversible antagonists of cholinesterase

Their effect in slowing progression of AD is modest. ACh is not the only cause

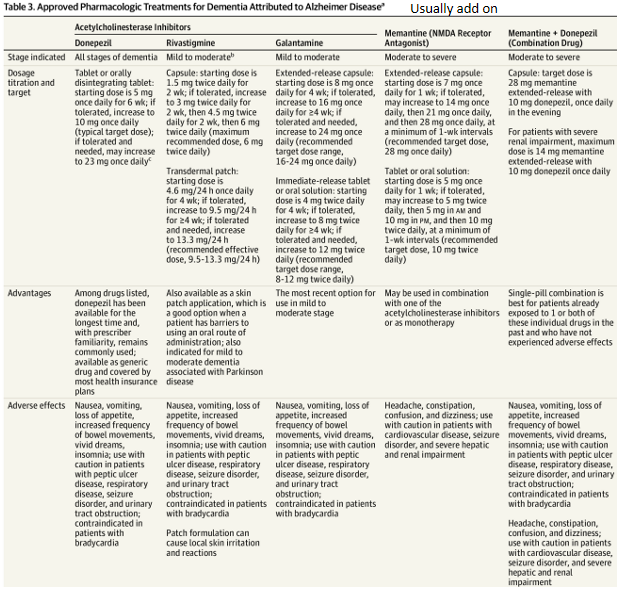

Recommendation for use

A slow-titration dosing regimen over 4 to 8 weeks is recommended to reach the target dose and minimize adverse effects

If adverse effects encountered, lower dosage temporarily (eg, days to weeks) before reescalating more slowly and monitoring for recurrence of adverse effects

Alternatively, the drug can be discontinued and a different AI

Monitoring:

A good response would result in the caregiver noticing a slight improvement in day-to-day life (eg, improved ability to function at home)

Routine cognitive tests (e.g. such as the MoCA)

Adverse effects: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and other cholinomimetic adverse effects, Related to increased GI motility

AD management - NMDA receptor antagonist

MOA

Memantine is an uncompetitive antagonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) type of glutamate receptors, located ubiquitously throughout the brain.

Memantine is a weak NMDA-antagonist which purportedly selectively inhibits excessive, pathological NMDA-receptor activation while preserves more physiological activation

Glutamate, the primary excitatory amino acid in the CNS, may contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD) by overstimulating various glutamate receptors leading to excitotoxicity and neuronal cell death.

Memantine may be considered :

For patients with moderate to severe dementia (switch therapy or first-line in new diagnosis)

Patients who cannot tolerate AI

Monitoring:

Caregiver feedback: improvement in day-to-day life activities (eg, improved ability to function at home)

Routine cognitive tests (e.g. such as the MoCA)

Adverse effects: confusion, dizziness, drowsiness, and headache

PK

Predominantly excreted unchanged in the urine

Long t1/2 of ~60-80 hrs

Better tolerated than cholinesterase inhibitors i.e. A/E uncommon but dizziness and confusion reported

AD management - treatment selection

The three acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine as monotherapies are recommended as options for managing mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease

Memantine monotherapy is recommended as an option for managing Alzheimer's disease for people with:

Moderate Alzheimer's disease who are intolerant of or have a contraindication to AChE inhibitors or

Severe Alzheimer's disease.

For people with an established diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease who are already taking an AChE inhibitor:

Consider memantine in addition to an AChE inhibitor if they have moderate disease

Offer memantine in addition to an AChE inhibitor if they have severe disease

AD management - Pharm treatment for dementia due to AD

AD management - Anti-amyloid therapy

Lecanemab (Leqembi®)

Anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody: Monoclonal antibody that binds to Aβ aggregates

FDA approved for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to be initiated in early AD (mild cognitive impairment [MCI] due to AD or mild AD dementia) with confirmed brain amyloid pathology

Landmark CLARITY-AD trial

First drug to demonstrate reduction of amyloid load and reduced (modest) cognitive decline

After ~20 years, new AD treatment was approved by FDA in 2021 (aducanumab) → controversial as it reduced Aβ levels but did not ameliorate clinical symptoms, discontinued since 2024

More recently, lecanemab and donanemab appears promising

Lecanemab - Criteria for consideration of use

Clinical diagnosis of MCI or mild AD dementia - DSF criteria

Positive amyloid PET or CSF studies indicative of AD

Age range 50–90 years, physician judgement for patients outside the age range

MMSE 22–30 or other cognitive screening instrument with a score compatible with early AD

BMI 18-34, physician judgement used for patients at the extremes of BMI

Patients may be on cognitive enhancing agents (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, or memantine) for AD

Patients may be on standard of care for other medical illnesses

Have a care partner or family member(s) who can ensure that the patient has the support needed to be treated with lecanemab

Patients, care partners, and appropriate family members should understand the requirements for lecanemab therapy and the potential benefit and potential harm of treatment

Lecanemab - Exclusion criteria

Any medical, neurologic, or psychiatric condition that may be contributing to the cognitive impairment or any non-AD MCI or dementia

More than 4 microhemorrhages (defined as 10 millimeter [mm] or less at the greatest diameter); a single macrohemorrhage >10 mm at greatest diameter; an area of superficial siderosis; evidence of vasogenic edema; multiple lacunar infarcts or stroke involving a major vascular territory; severe small vessel; or other major intracranial pathology

MRI evidence of a non-AD dementia

Recent history (within 12 months) of stroke or transient ischemic attacks or any history of seizures

Mental illness (e.g, psychosis) that interferes with comprehension of the requirements, potential benefit, and potential harms of treatment and are considered by the physician to render the patient unable to comply with management requirements

Major depression that will interfere with comprehension of the requirements, potential benefit, and potential harms of treatment; patients for whom disclosure of a positive biomarker may trigger suicidal ideation. Patients with less severe depression or whose depression resolves may be treatment candidates

Any history of immunologic disease (e.g., lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease) or systemic treatment with immunosuppressants, immunoglobulins, or monoclonal antibodies or their derivatives

Patients with a bleeding disorder that is not under adequate control (including a platelet count <50,000 or international normalized ratio [INR] >1.5 for participants who are not on anticoagulant)

Patients on anticoagulants (coumadin, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban, apixaban, betrixaban, or heparin) should not receive lecanemab; tPA should not be administered to individuals on lecanemab - higher risk of brain bleed

Unstable medical conditions that may affect or be affected by lecanemab therapy

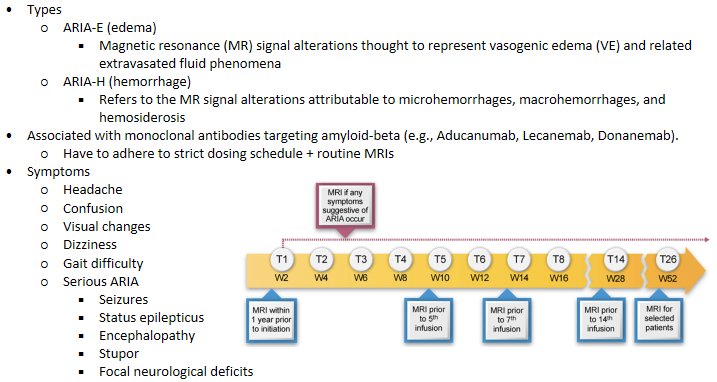

Lecanemab - Amyloid‐related imaging abnormalities (ARIA)

Lecanemab - APOE Genotyping When Considering Lecanemab Treatment

APOE in humans has three alleles:

APOE ε3 (APOE3) is most common

APOE ε2 (APOE2) is least common and reduces the risk of AD

APOE ε4 (APOE4), present in ~20–25% of the population,

APOE4 genotype increases the risk of clinical AD

APOE4 carriers (especially homozygotes) are at increased risk for ARIA, symptomatic ARIA, and recurrent ARIA

APOE genotyping of all treatment candidates is recommended before initiating lecanemab therapy.

Genetic Counselling recommended for APOE4 carriers and their biological family members

AD management - medication management

usually for older pt

Reduce polypharmacy

Review medications that may contribute to cognitive impairment

Assist caregiver on medication management issues e.g. simplify medication regimen, arrangement for medication refill

Evaluate risk/benefit of existing medications (e.g. antithrombotics)

AD management - Non-pharmacologic approaches

Cognitively stimulating activities (eg, reading, games)

Physical exercise (eg, aerobic and anaerobic)

Social interactions with others (eg intentional abt building community)

Healthy diet such as the Mediterranean diet (eg, high in green leafy vegetables)

Adequate sleep (eg, uninterrupted sleep and with sufficient number of hours)

Proper personal hygiene (eg, regular bathing)

Safety, including inside the home (eg, using kitchen appliances) and outside (eg, driving)

Medical and advanced care directives (eg, designation of power of attorney)

Long-term health care planning (eg, for living arrangements in the late stage of dementia)

Financial planning (eg, for allocation of assets)

Effective communication (eg, for expressing needs and desires, such as with visual aids)

Psychological health (eg, participating in personally meaningful activities, such as playing music)

AD management - Behavioural and psychological symptoms (BPSD)

“Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)” refers to the spectrum of non-cognitive and non-neurological symptoms of dementia, such as agitation, aggression, psychosis, depression and apathy.

Often an attempt by the patient to communicate - therefore understanding why the behaviour or symptom is occurring is the key to management

At least 80% of people with dementia experience BPSD.

Depression and anxiety can be among the first symptoms of dementia, while agitation and aggression more commonly occur later, especially as the person’s ability to communicate and influence their environment diminishes.

BPSD can be extremely stressful for the person and their family and carers

Appropriate treatment of BPSD can significantly improve the quality of life of the patient and their families.

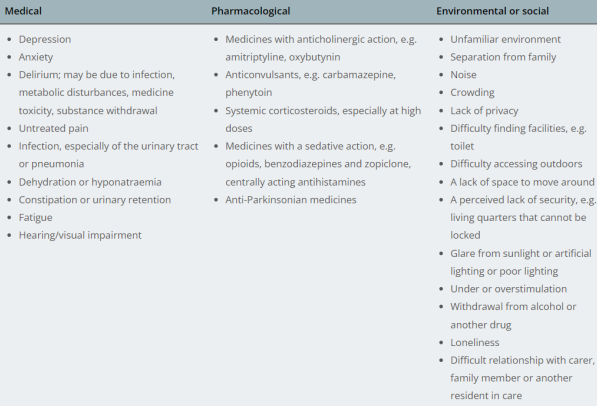

BPSD - Factors contributing to BPSD

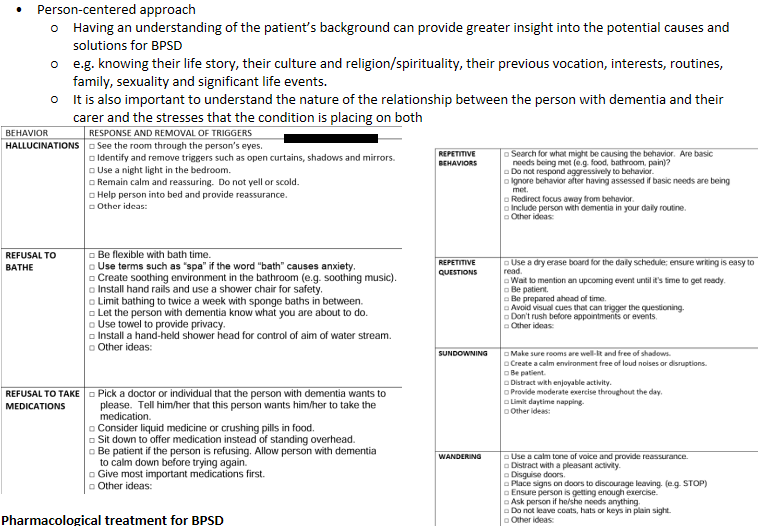

BPSD - Non-pharmacologic management

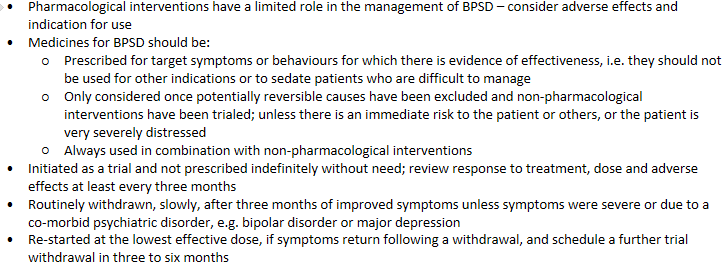

BPSD - pharm management

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): Should generally not be prescribed to patients with dementia as the anticholinergic effects may further disrupt cognition

BPSD management - Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Effective for the management of depression and anxiety in people with dementia that cannot be managed by non-pharmacological interventions alone.

Citalopram has been shown to reduce agitation in patients with AD, may improve other symptoms of BPSD, such as delusions

Consider dose-dependent risk of increased QT-prolongation and worsening cognition needs to be balanced against the benefit of treatment

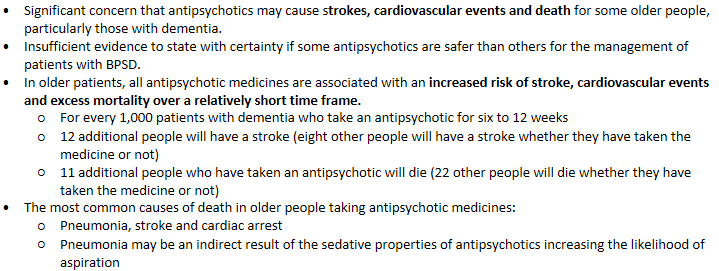

BPSD management - Antipsychotics

Are only appropriate for patients with BPSD if aggression, agitation or psychotic symptoms are causing severe distress or an immediate risk of harm to the patient or others or if the patient has a pre-existing, co-morbid mental illness where antipsychotics are indicated.

Only modestly effective in managing BPSD, and the level of effectiveness varies between patients

Unlikely to be beneficial for wandering, calling out, social withdrawal or inappropriate sexualised behaviour in people with dementia

Less likely to be effective for intermittent but challenging behaviours that are closely related to clear environmental triggers, e.g. aggression that only occurs during personal cares

BPSD management - older pt

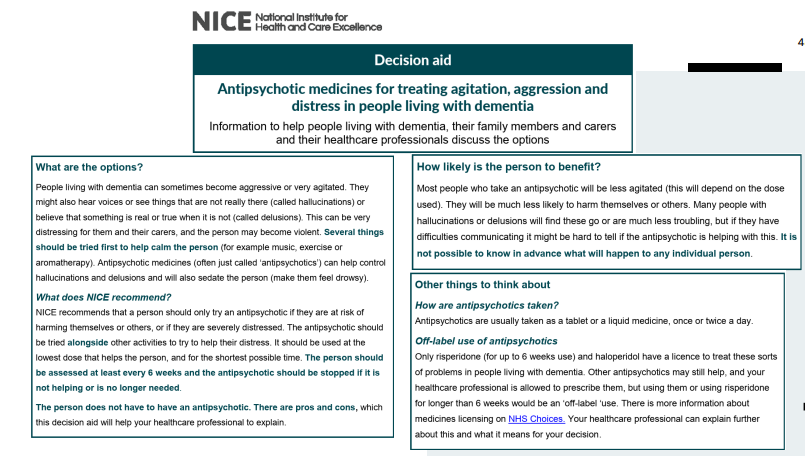

BPSD management - decision aid

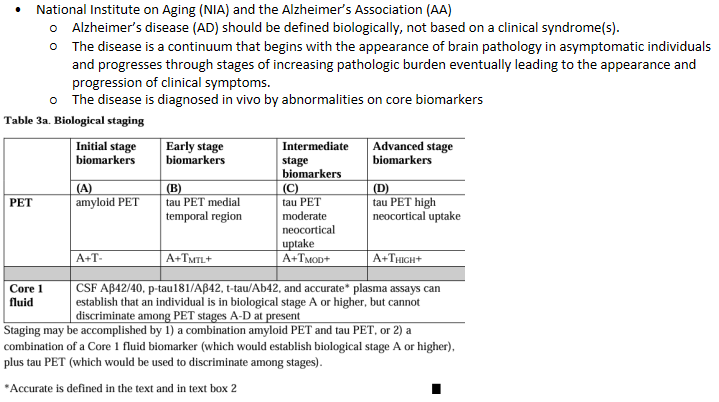

Revised criteria for diagnosis & staging of Alzheimer’s Disease (Draft)

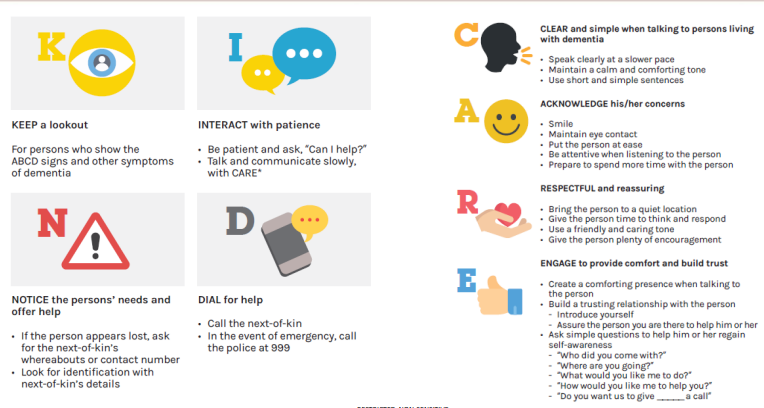

AD care coordination - Community Resources

AD care coordination - Non-verbal communication

Eye contact : Are you looking at the person you are talking to or looking somewhere else?

Facial expression: Do you frown or smile when you speak?

Hand & Body Gesture: Do you clench your fists and shrug your shoulders or are you relaxed?

Stand/seated face to face at same level

Don’t stand or sit too close

Give visual cues

If the person appears lost

Show your own identity card (IC) and ask: “Do you have this?”

Don’t ask: “Do you have IC?”

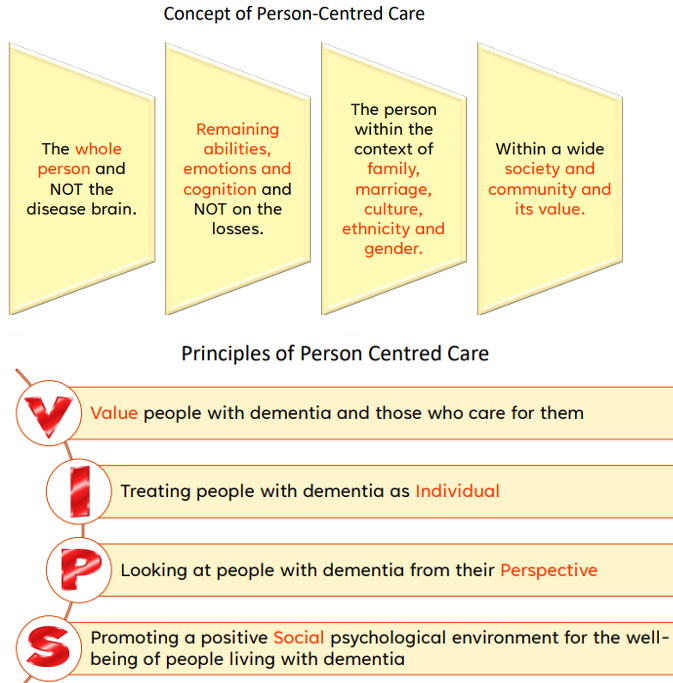

AD care coordination - Person-Centred Care