Forensic Chem Exam 3

1/107

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

108 Terms

Questioned Documents

Any object which contains handwritten or printed material, whose source or authenticity is in doubt

3 steps of analysis for a questioned document

Static V Dynamic Exam Approaches

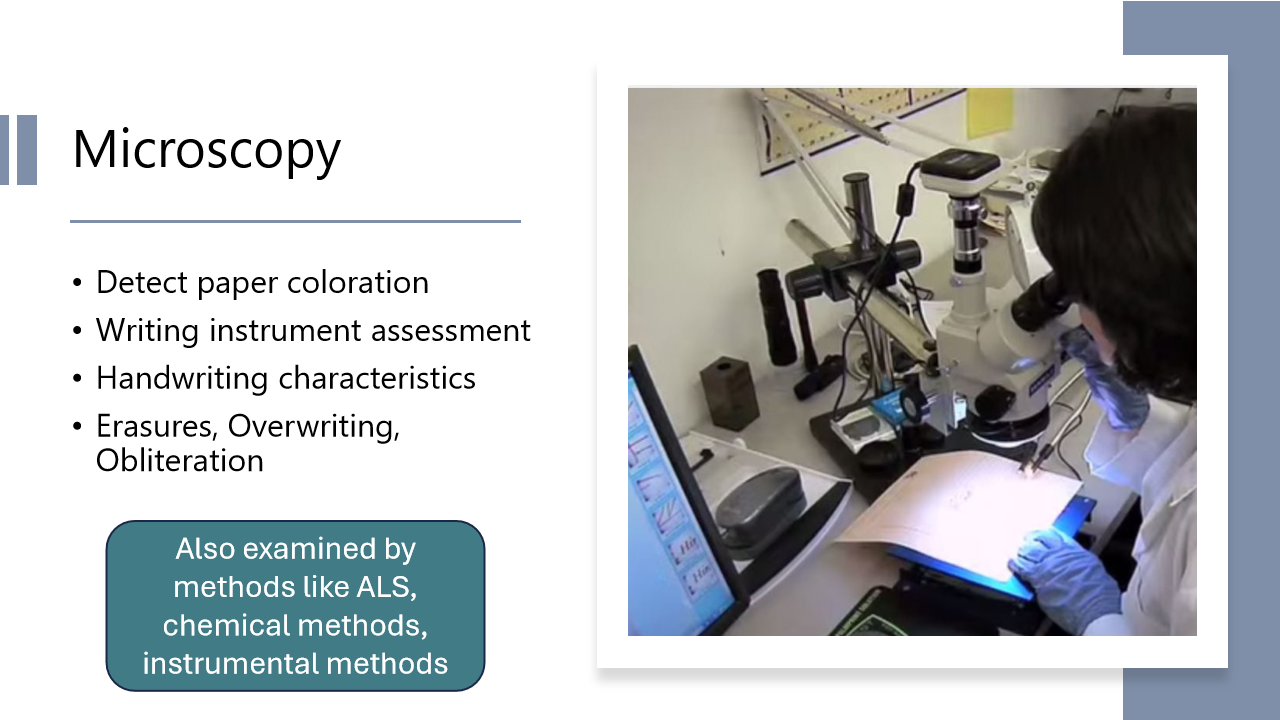

Microscopy of handwritten documents

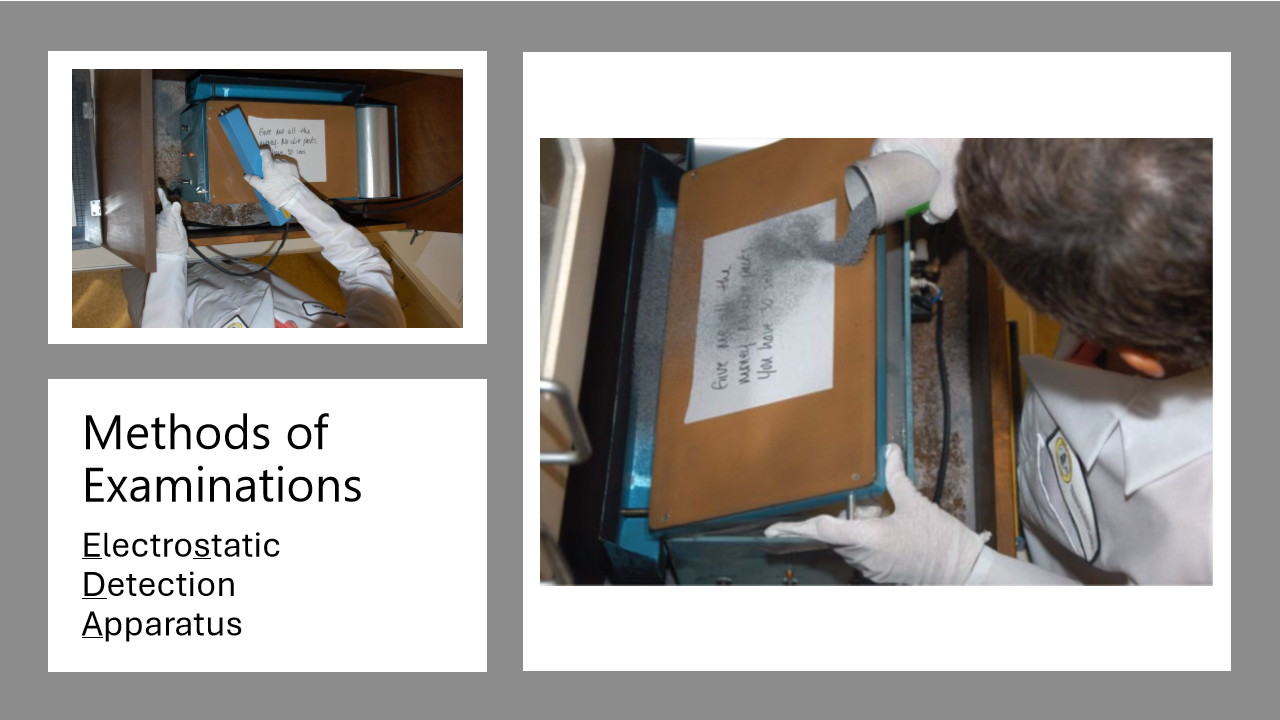

Exam methods for indented documents

Ink Composition: Colorants

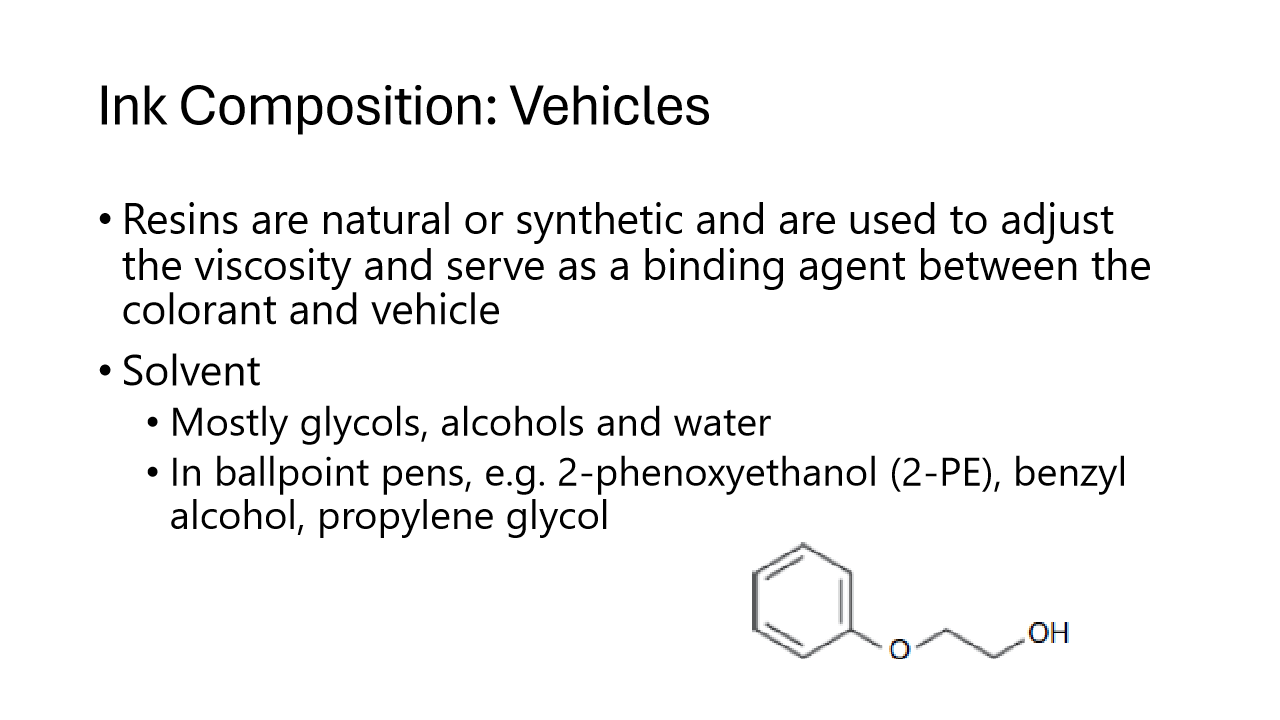

Ink Composition: Vehicles (Resins and Solvents)

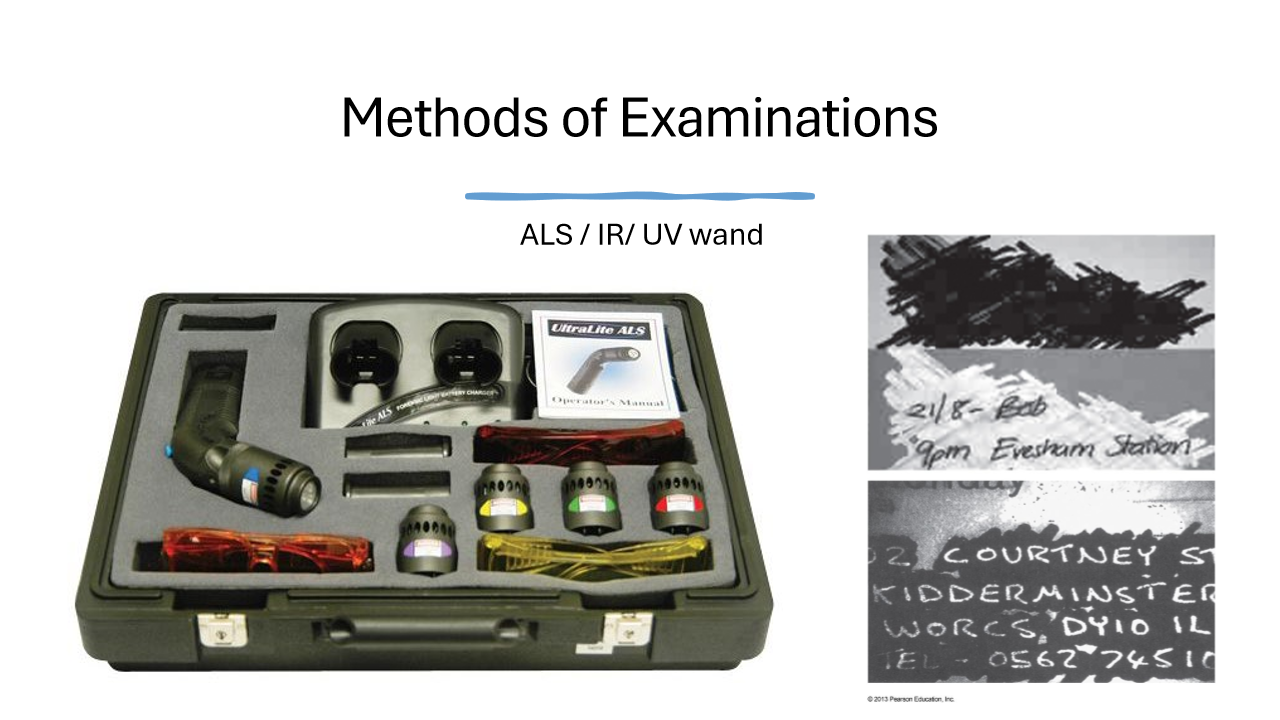

Exam methods for obliterations

Paint

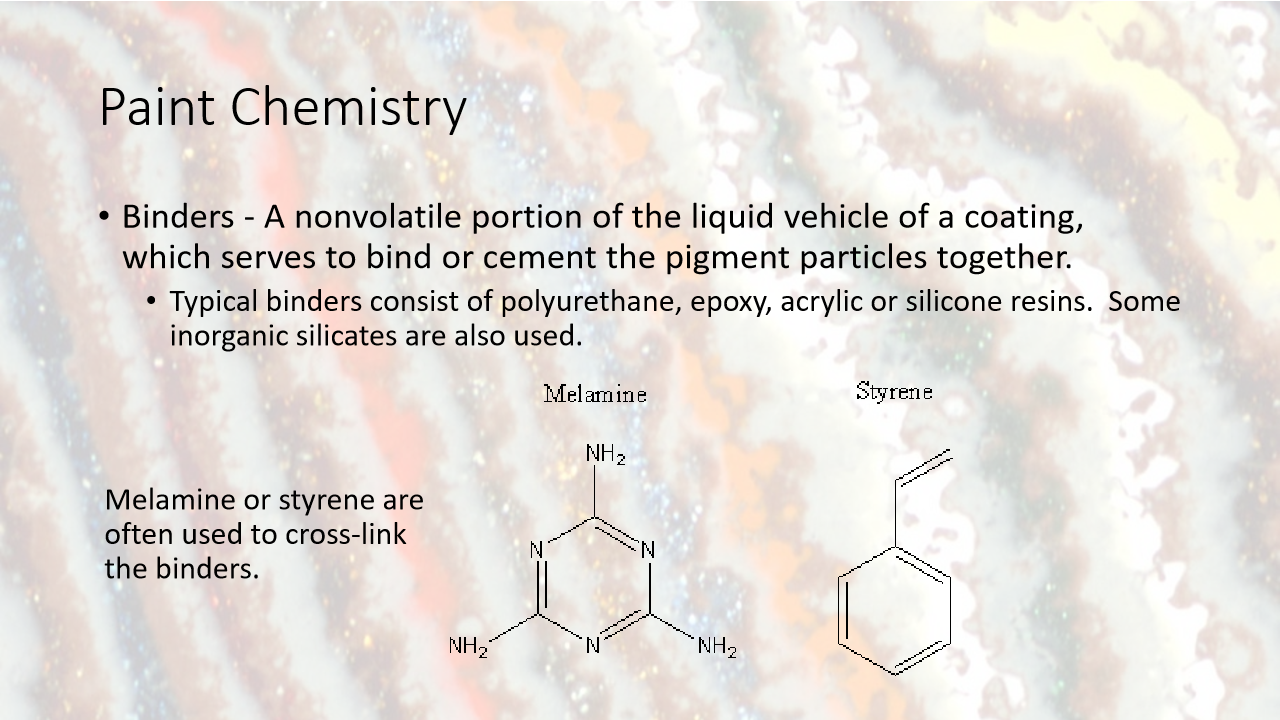

Binders

Dyes and Pigments

Additives

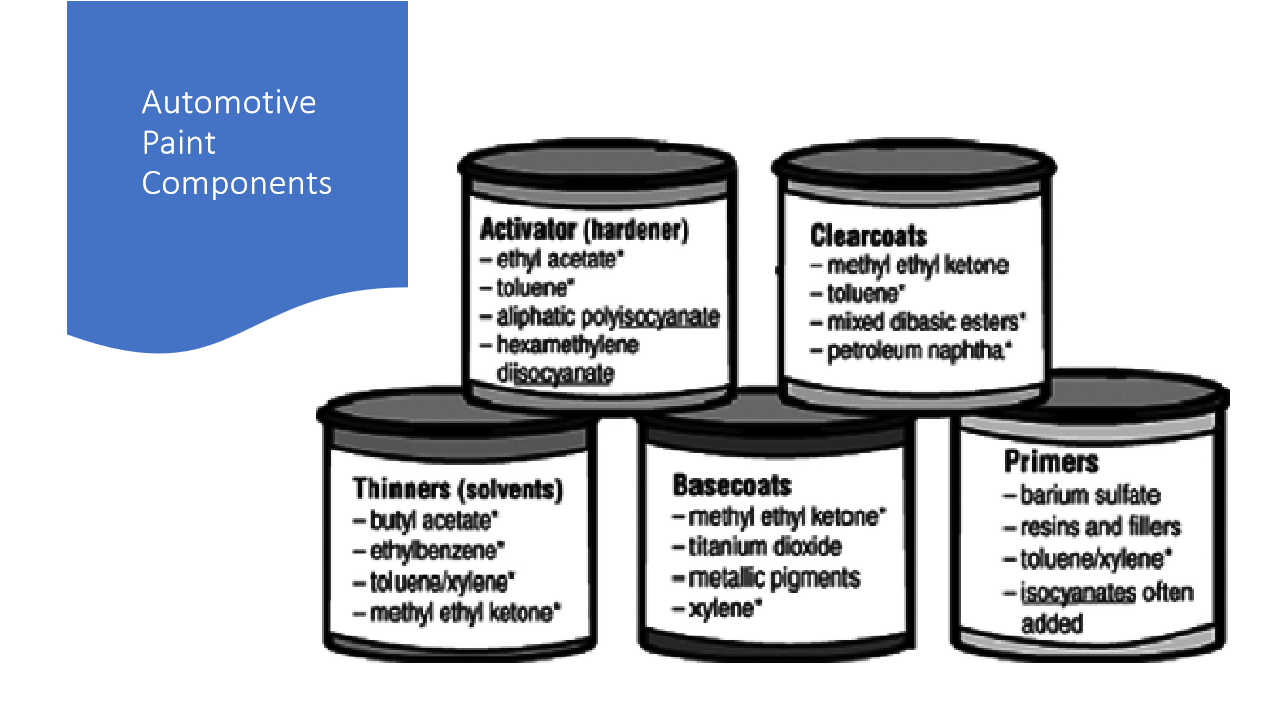

5 components of automotive paints

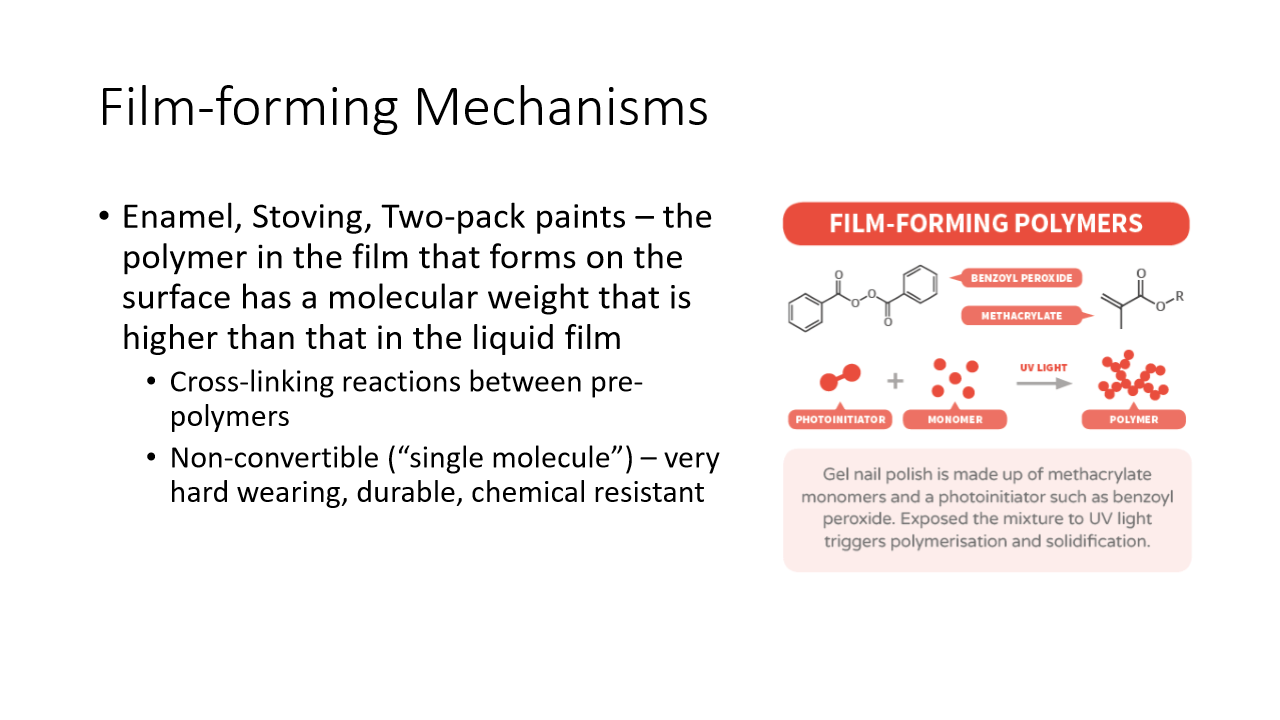

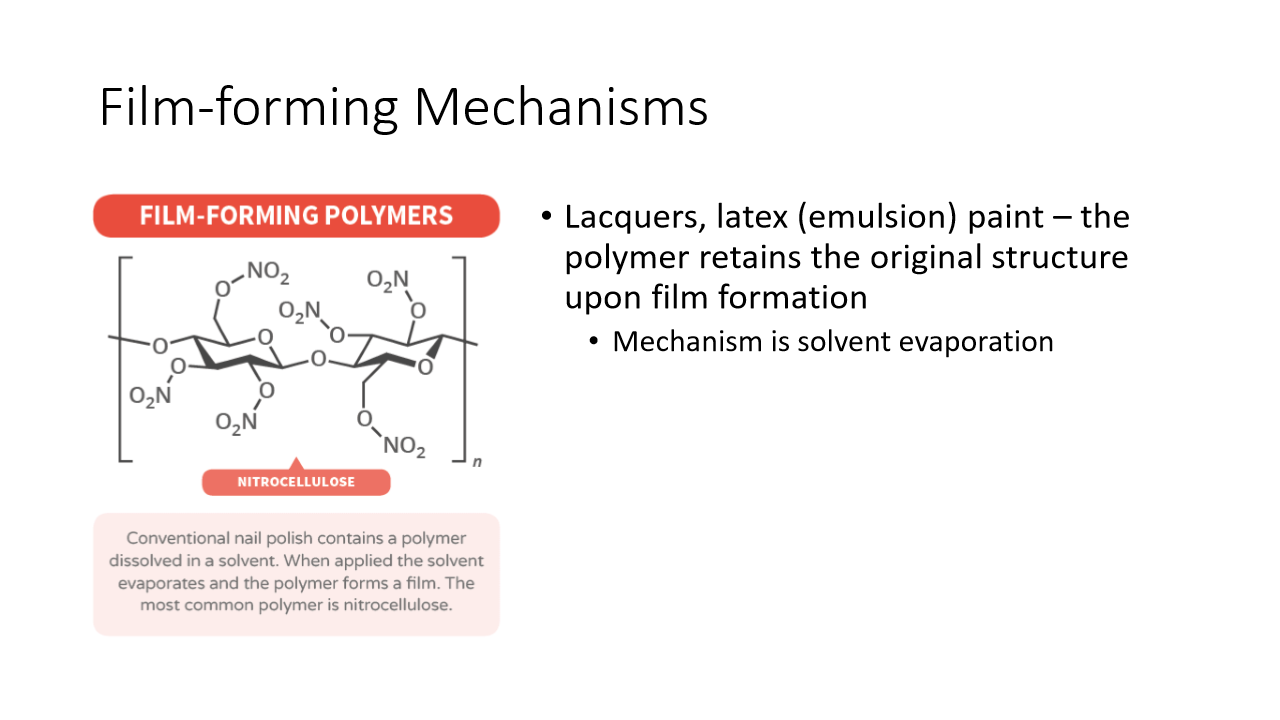

Film-forming mechanisms

Laquers

Automotive Paint Layers

Analytical Scheme of Paint

Automotive paint layers (order)

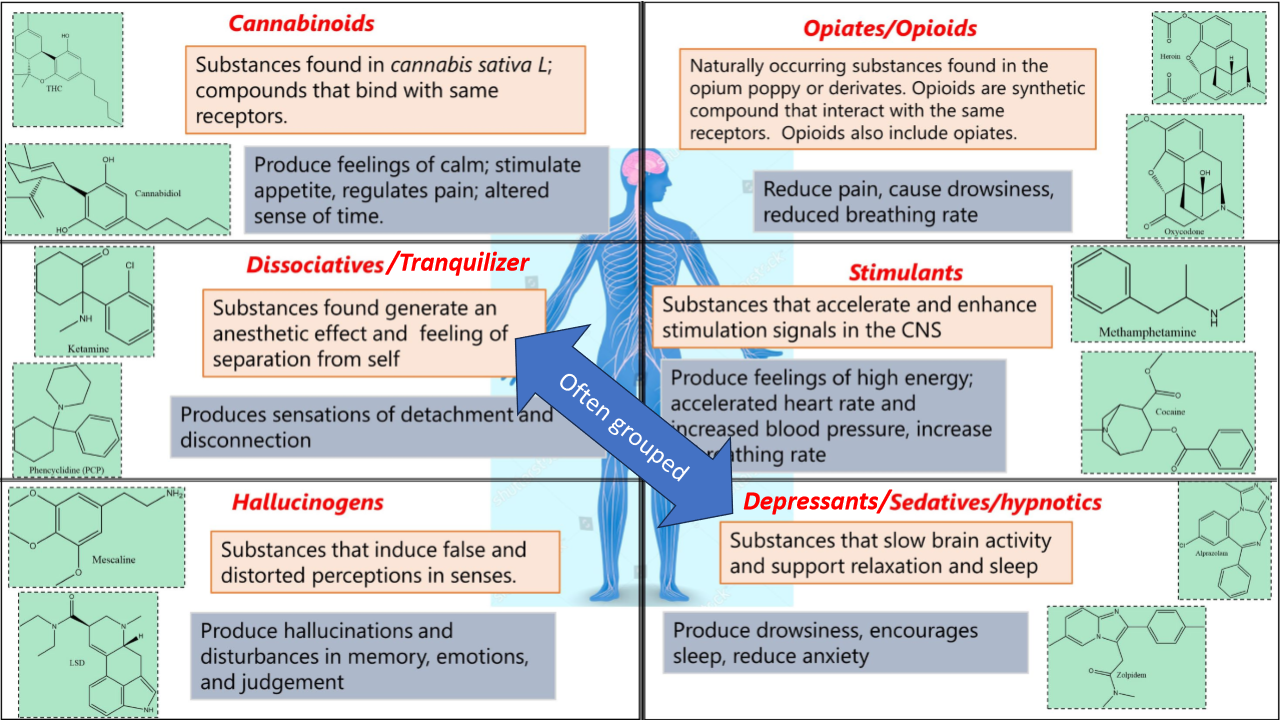

6 Classes of Drugs

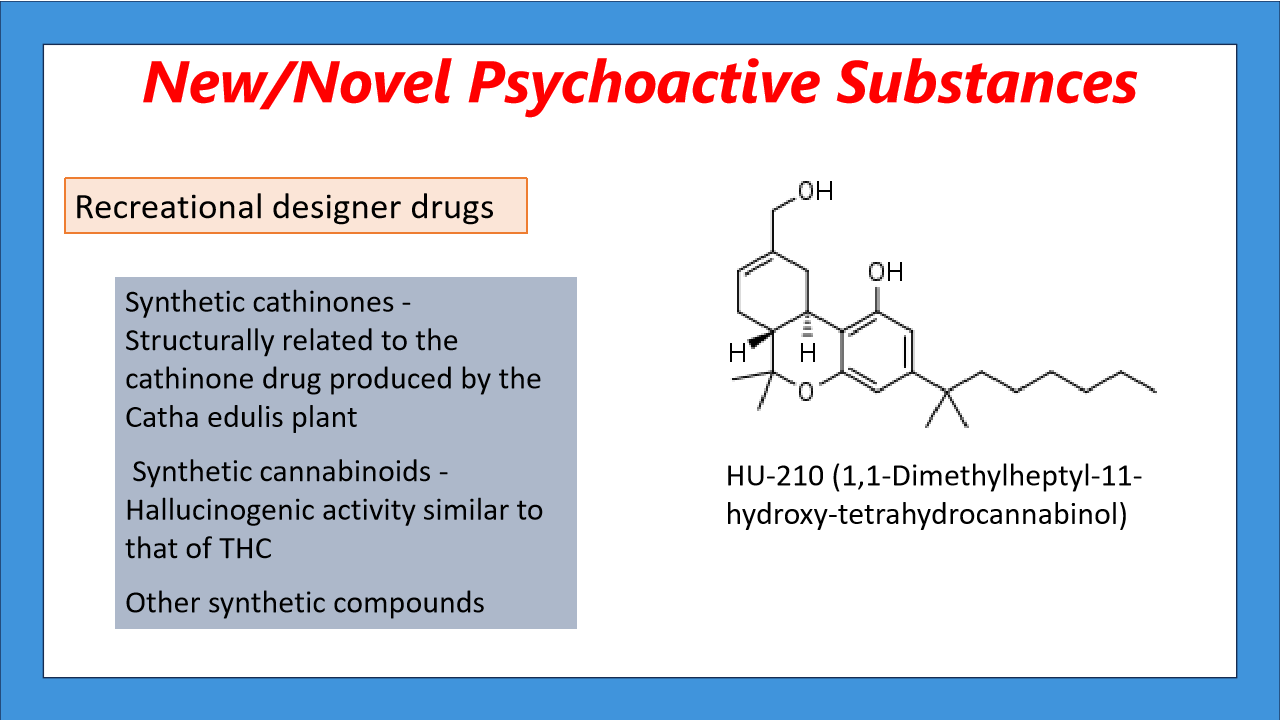

NPS

4 steps of seized drug analysis

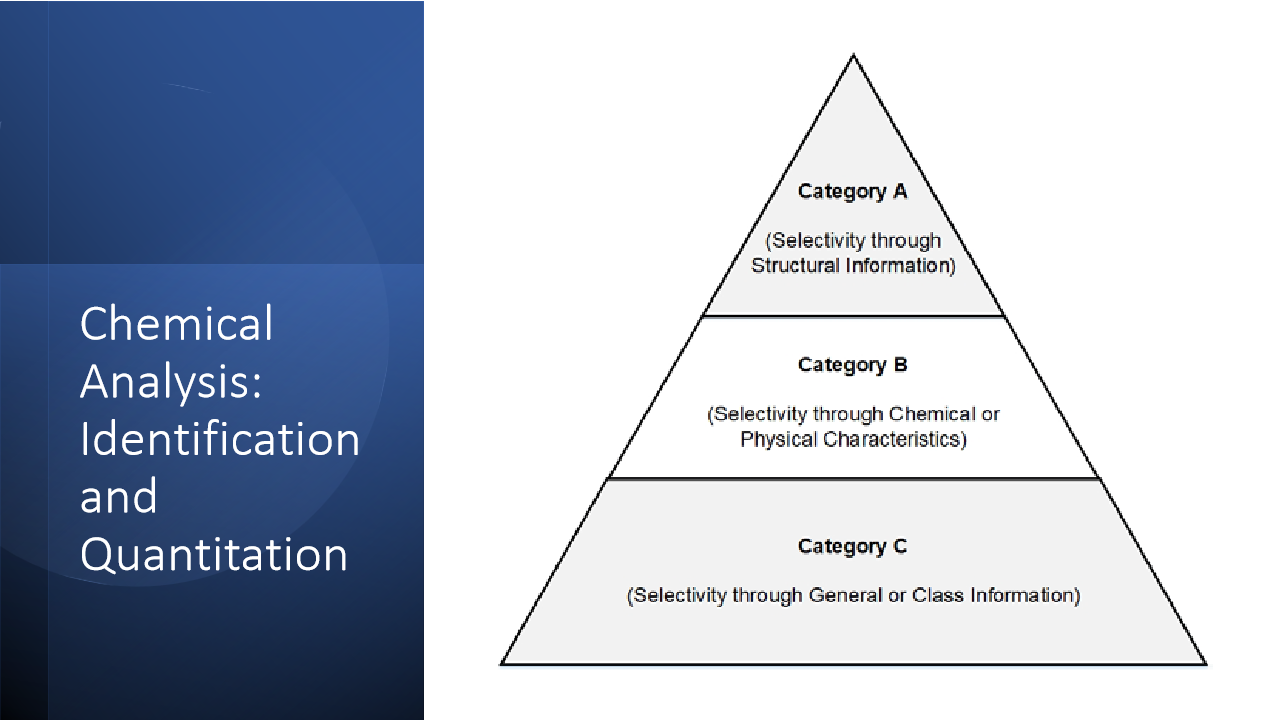

Chemical Analysis 3 Categories

Color Tests

Marquis Test

Marquis General Mechanism

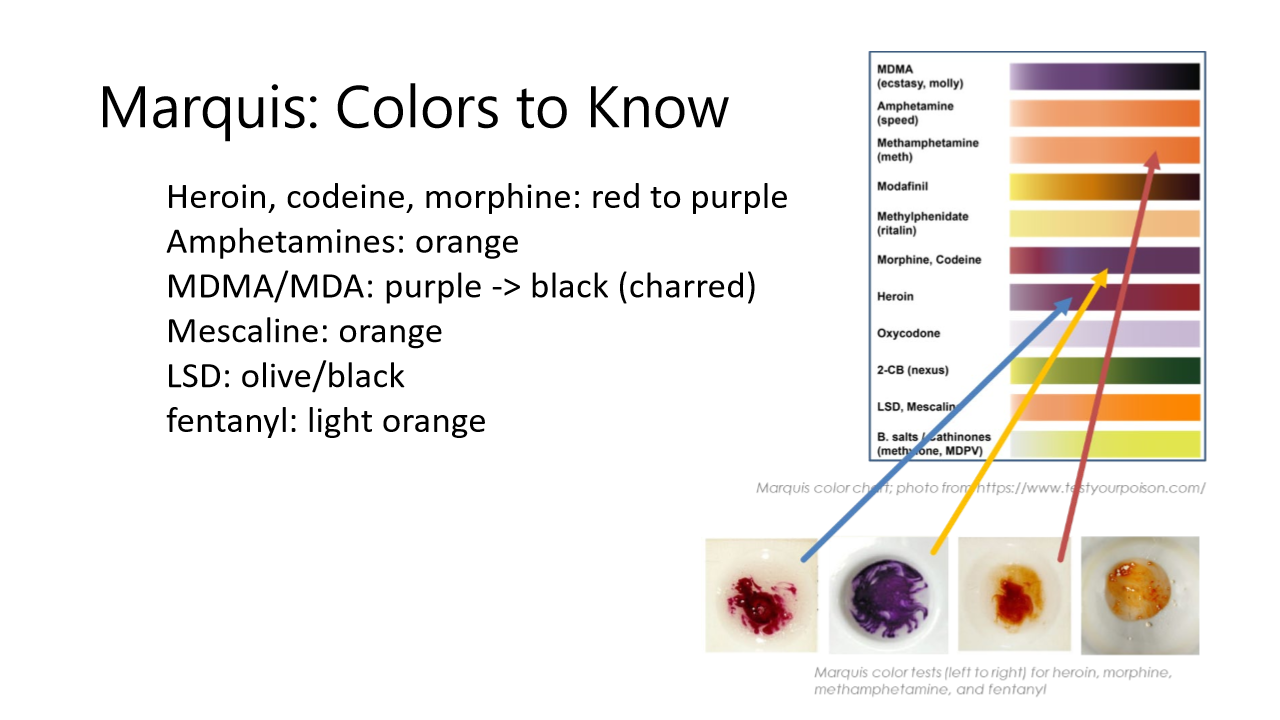

Marquis Colors to Know

Mecke Test

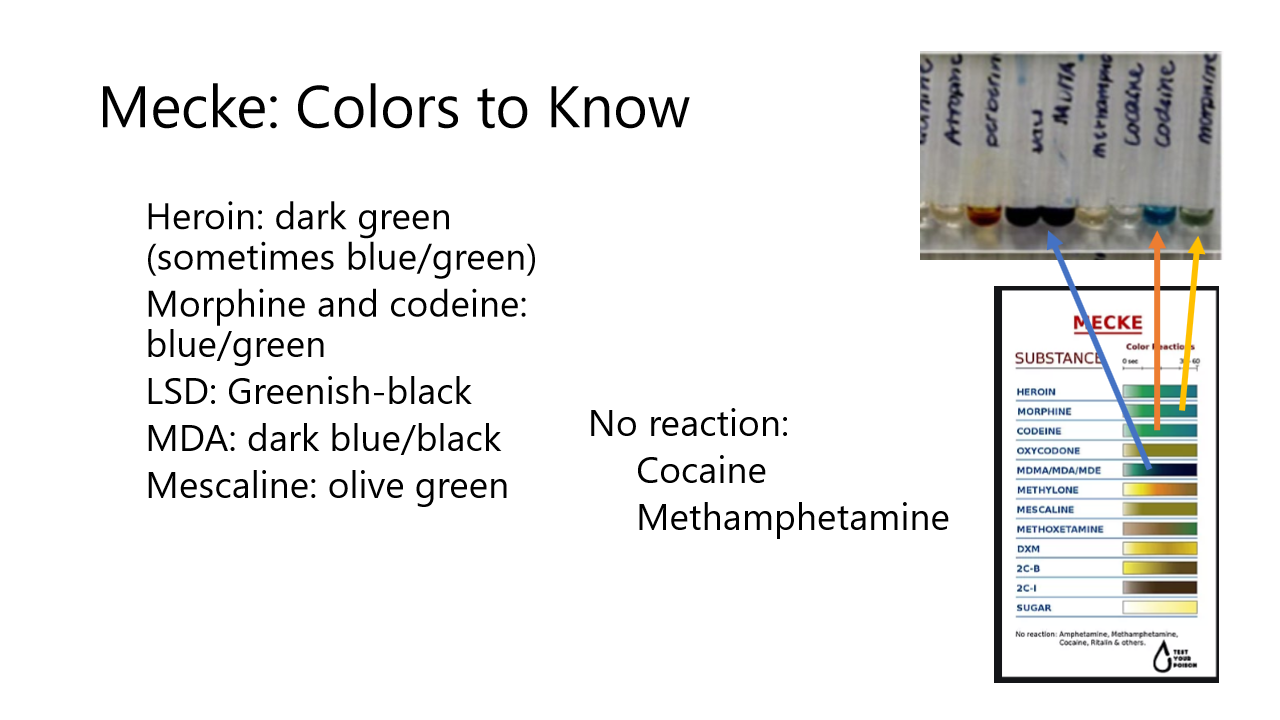

Mecke Colors to Know

Froehde Test

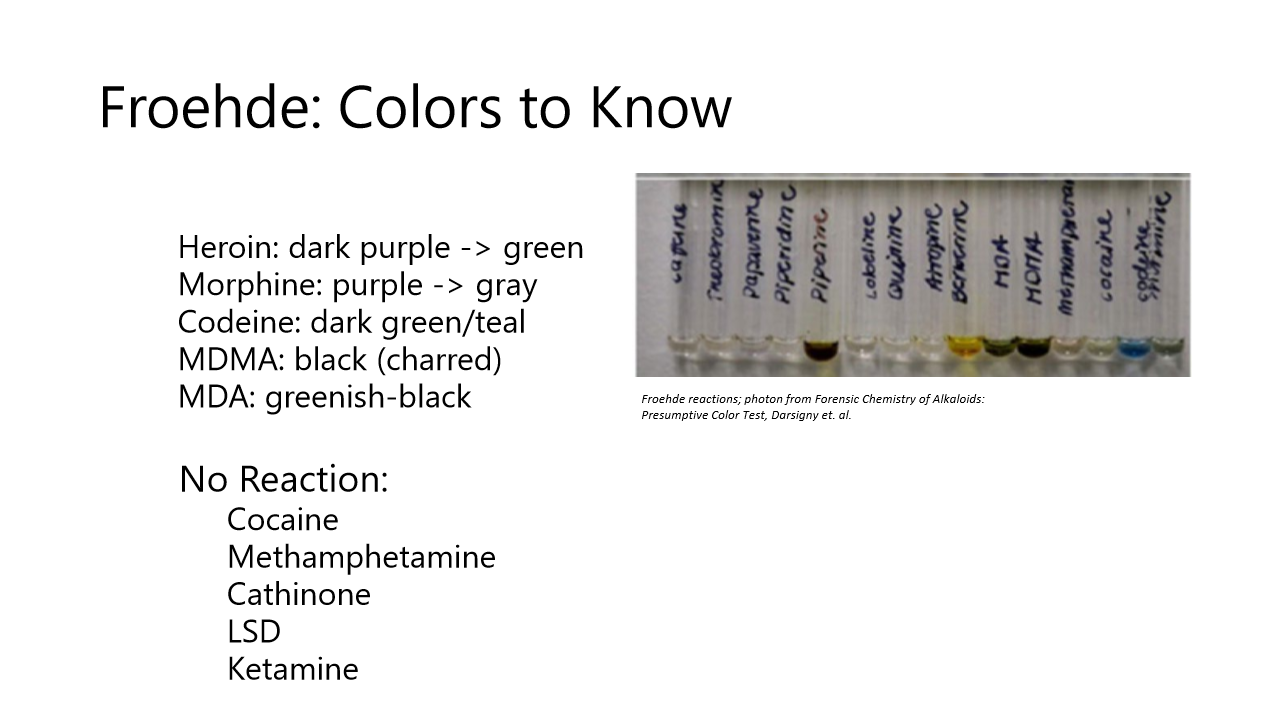

Froehde Colors to Know

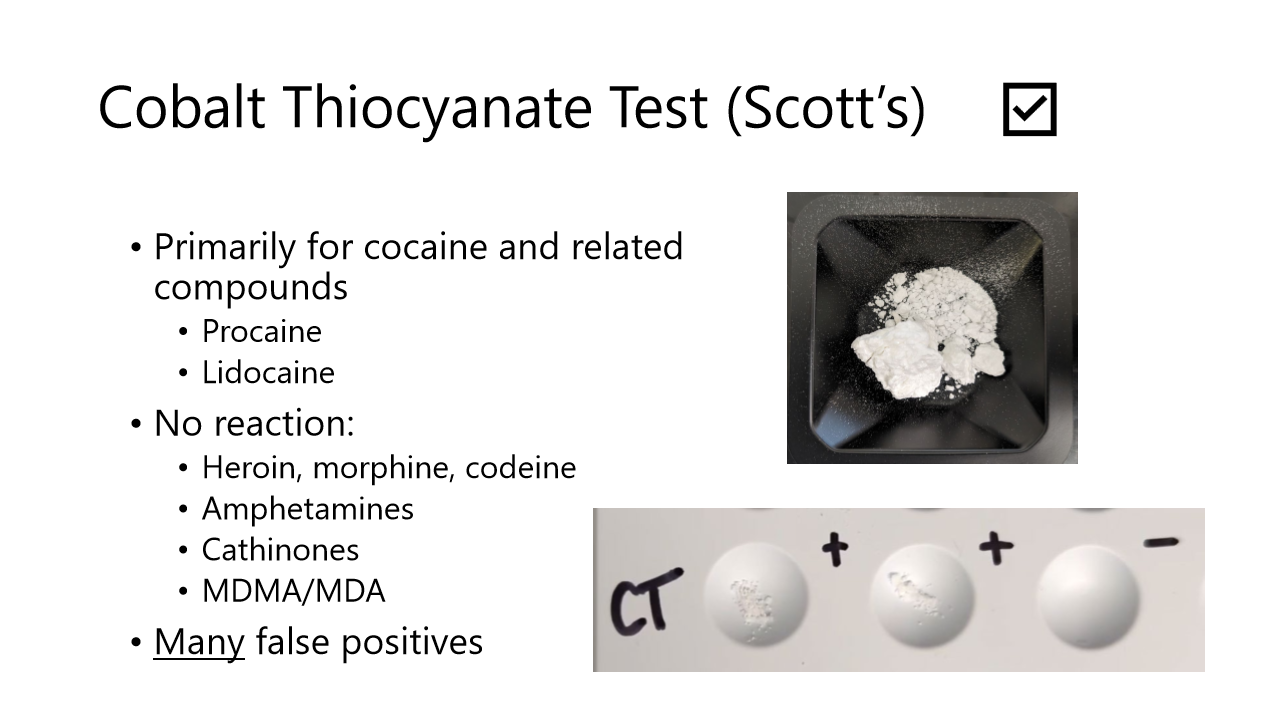

Scott’s Test

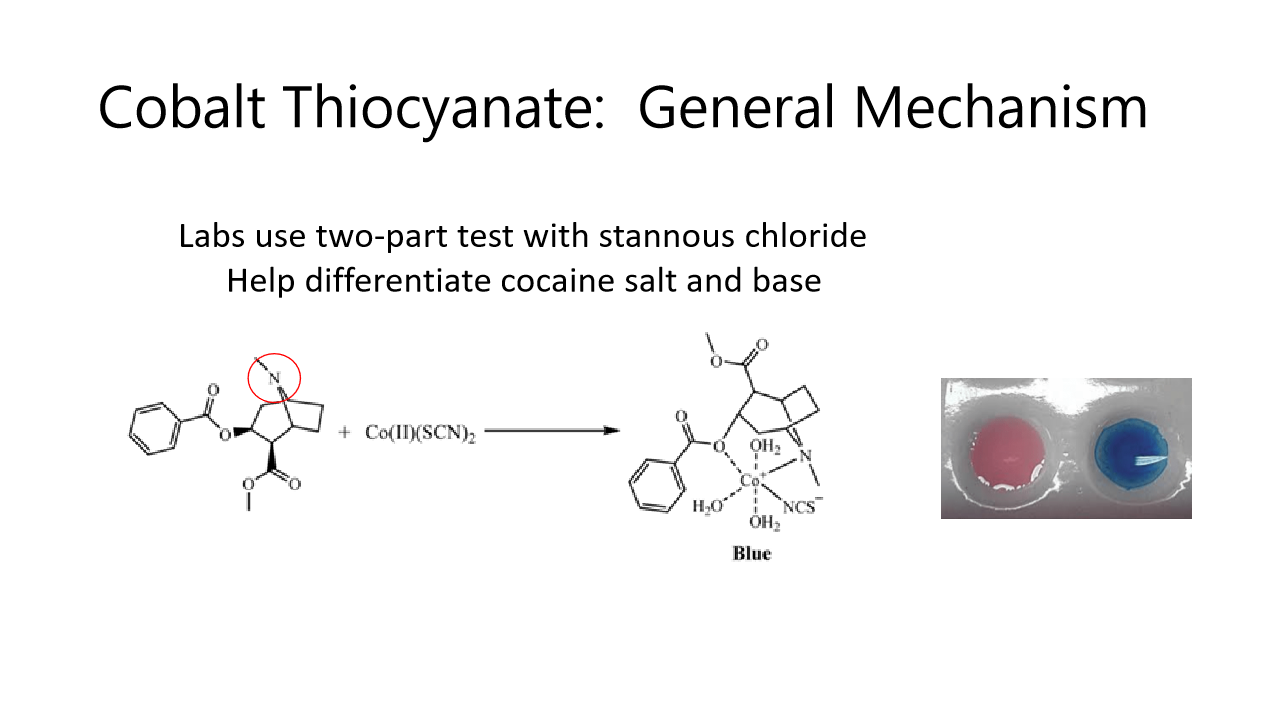

Cobalt Thiocyanate General Mechanism

Mandelin Test

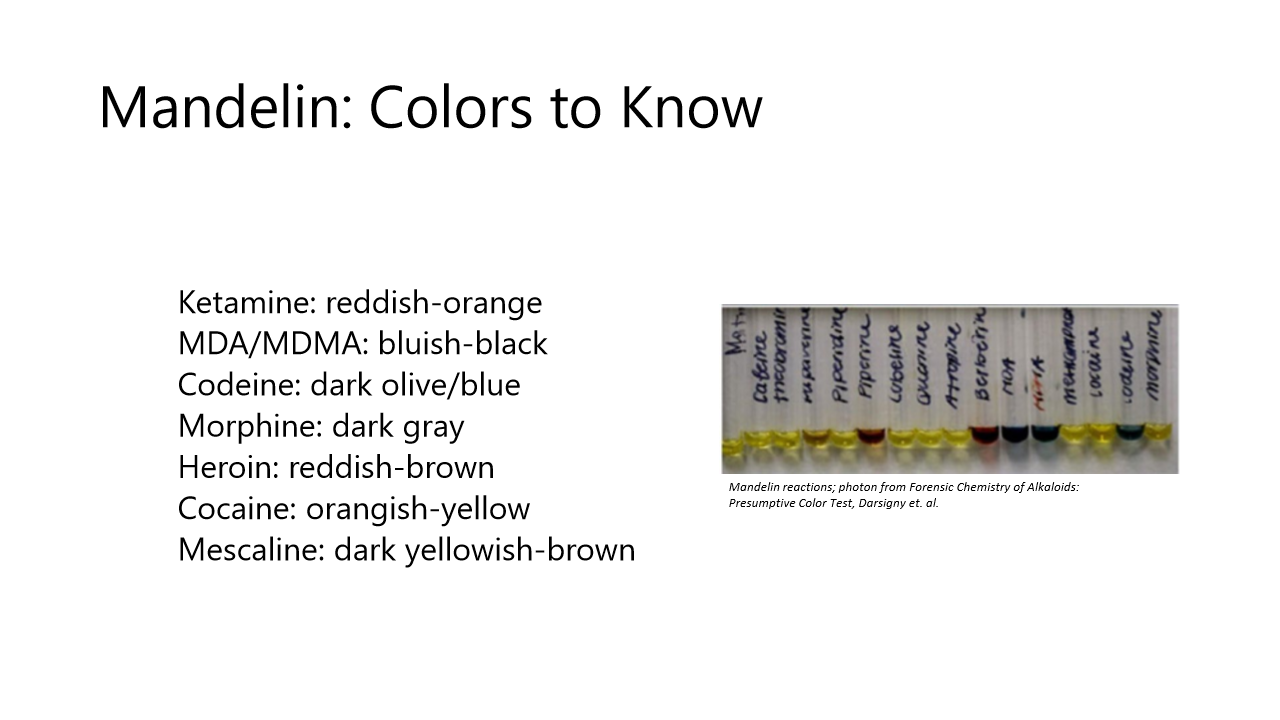

Mandelin Colors to Know

Sodium Nitroprusside Color Test

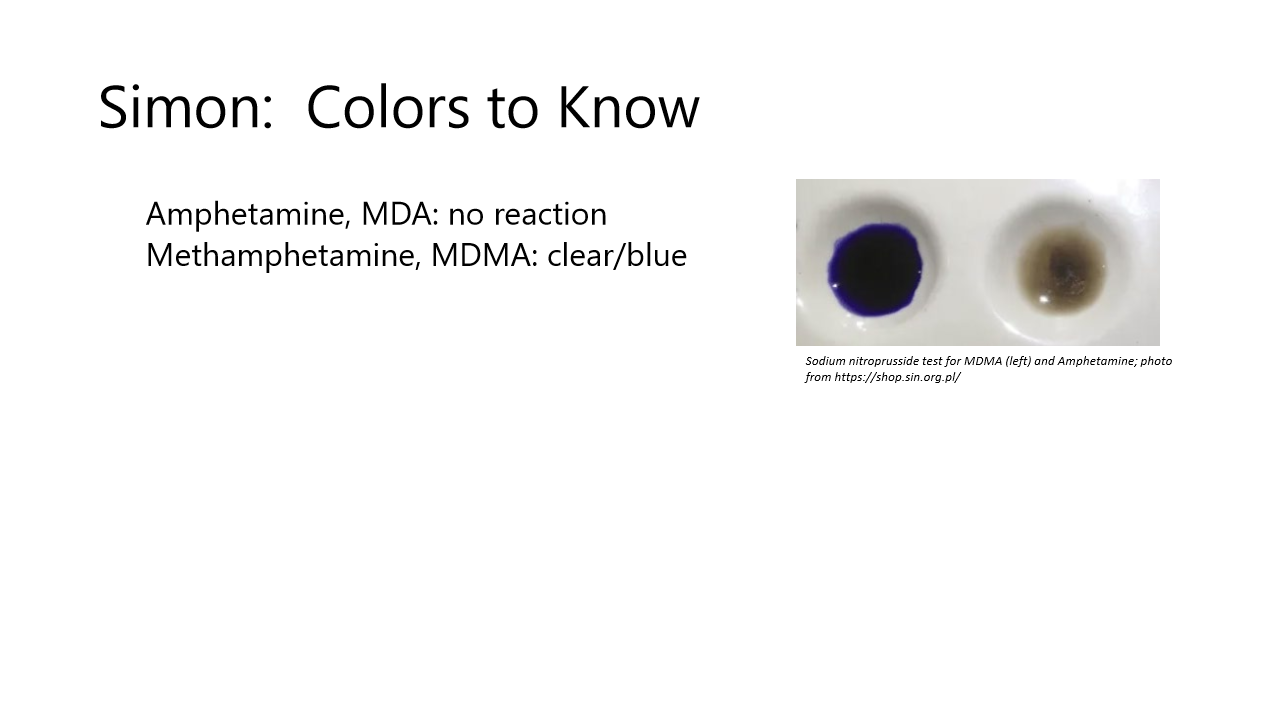

Simon Test Colors to Know

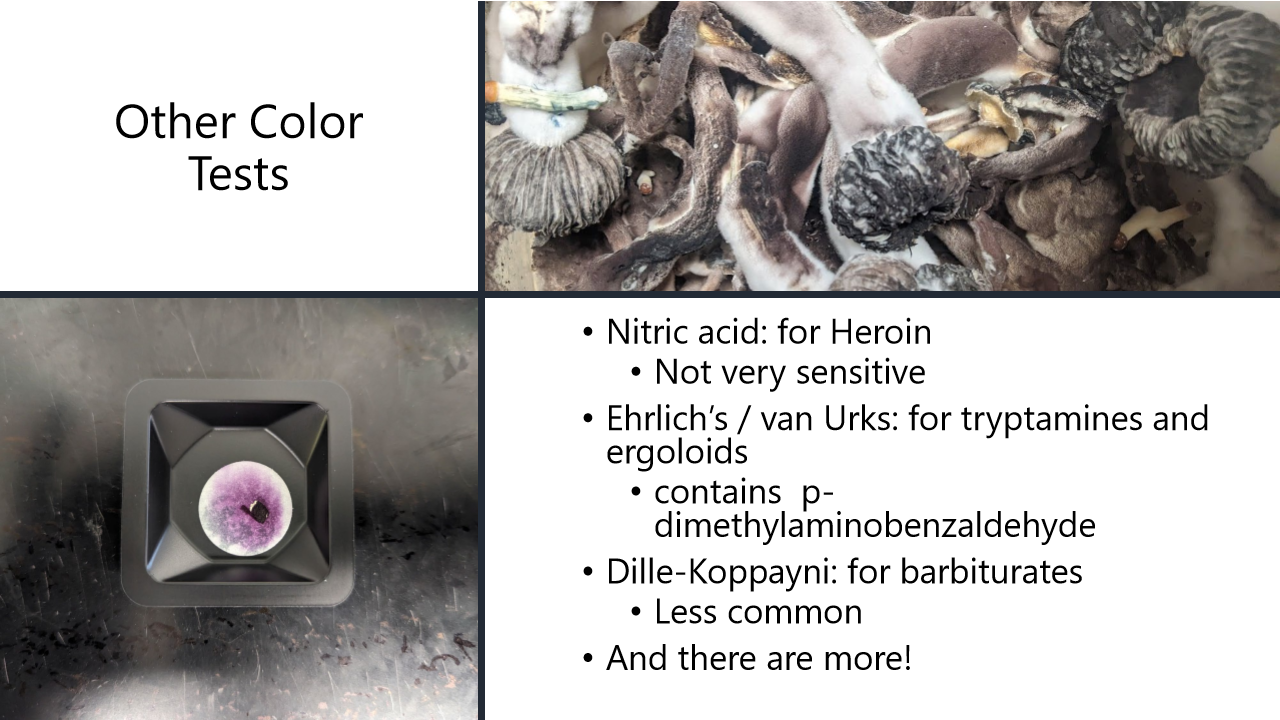

3 other color tests

Duquenois Levine Color Test

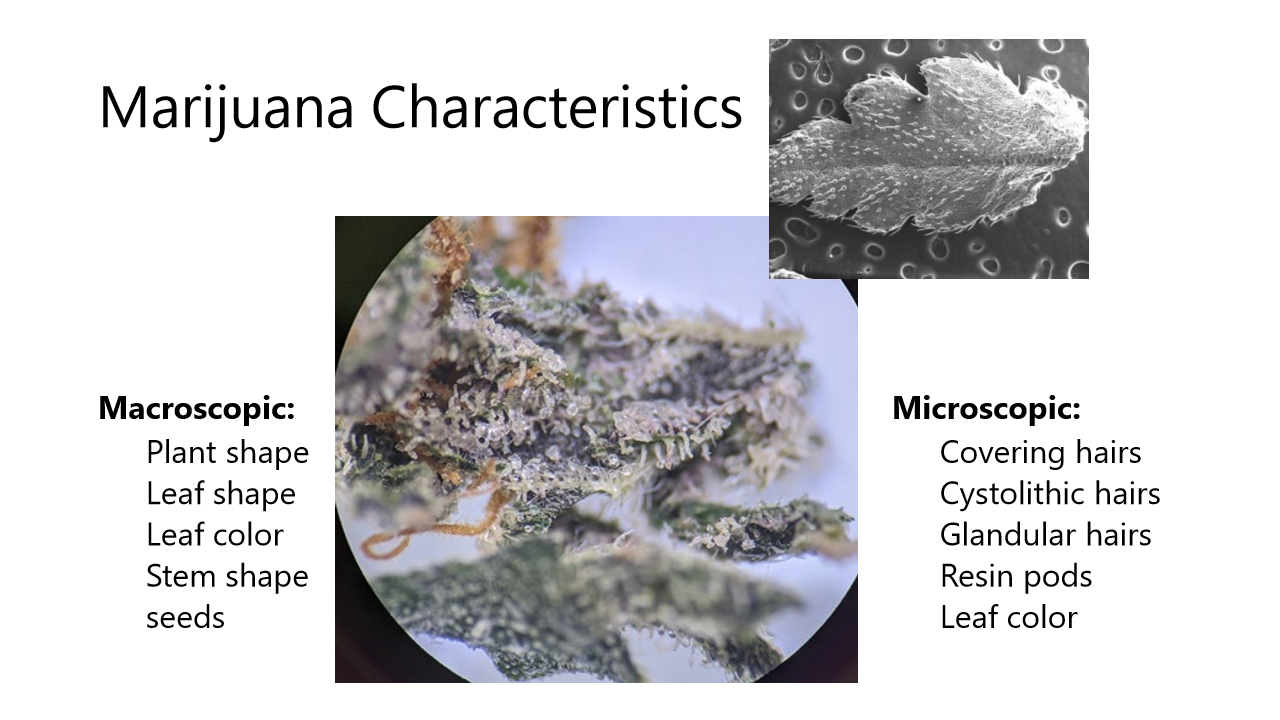

Marijuana Characteristics

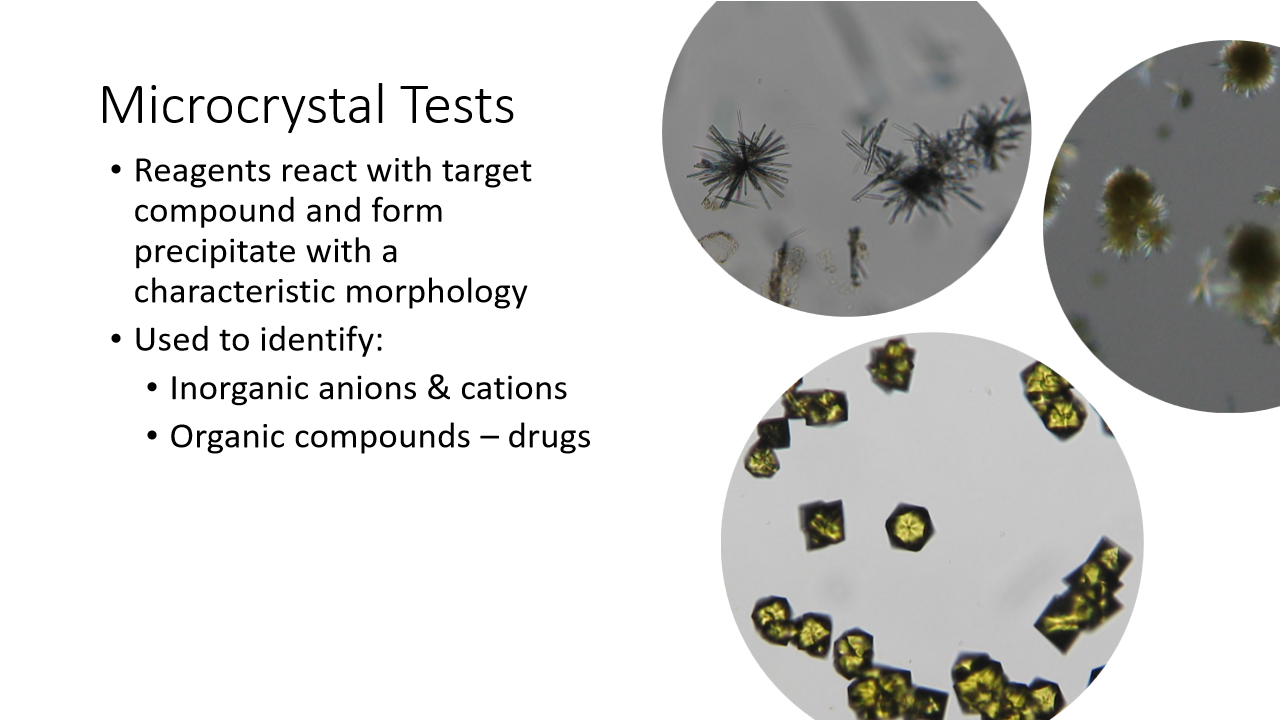

Microcrystal Tests

Forensic Toxicology

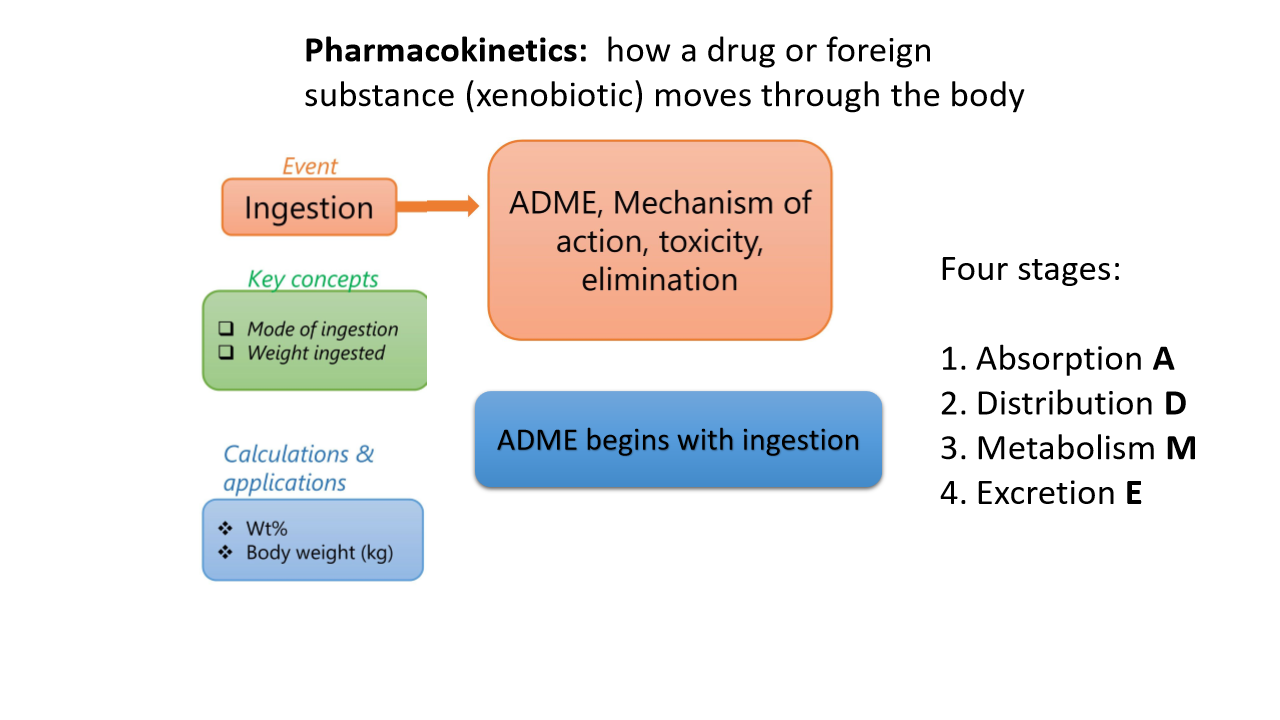

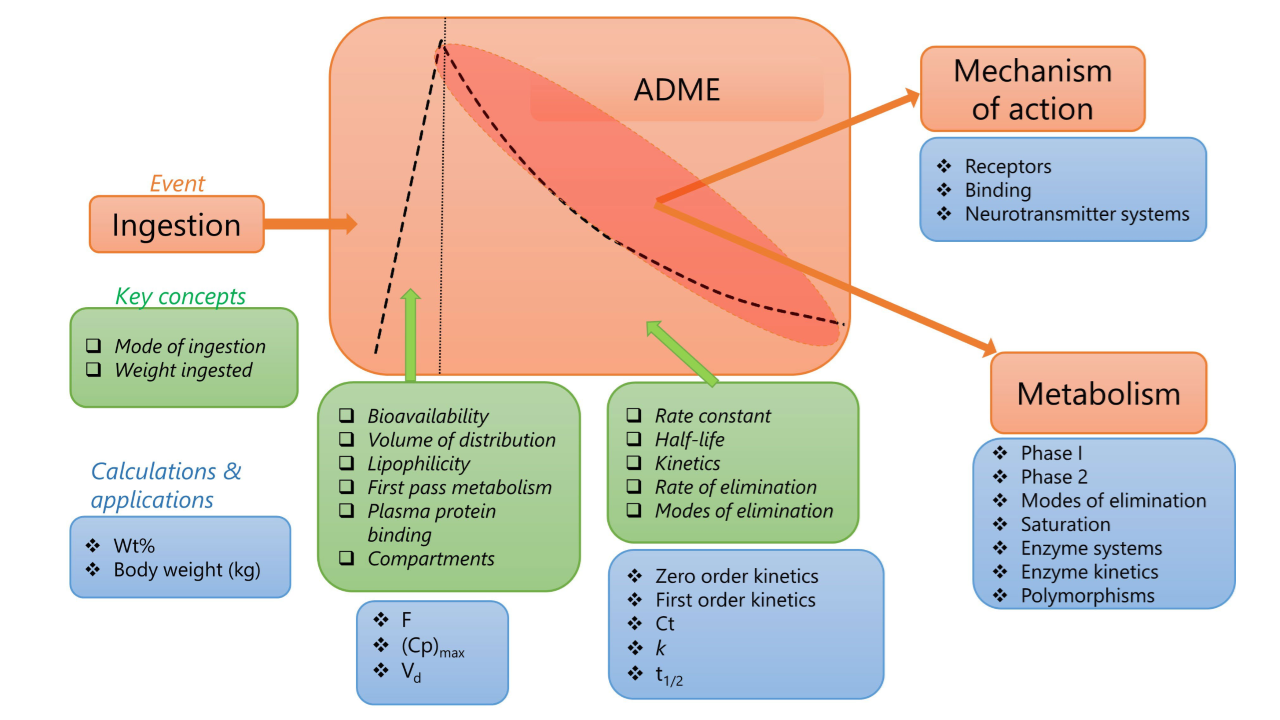

Pharmacokinetics and 4 stages

ADME

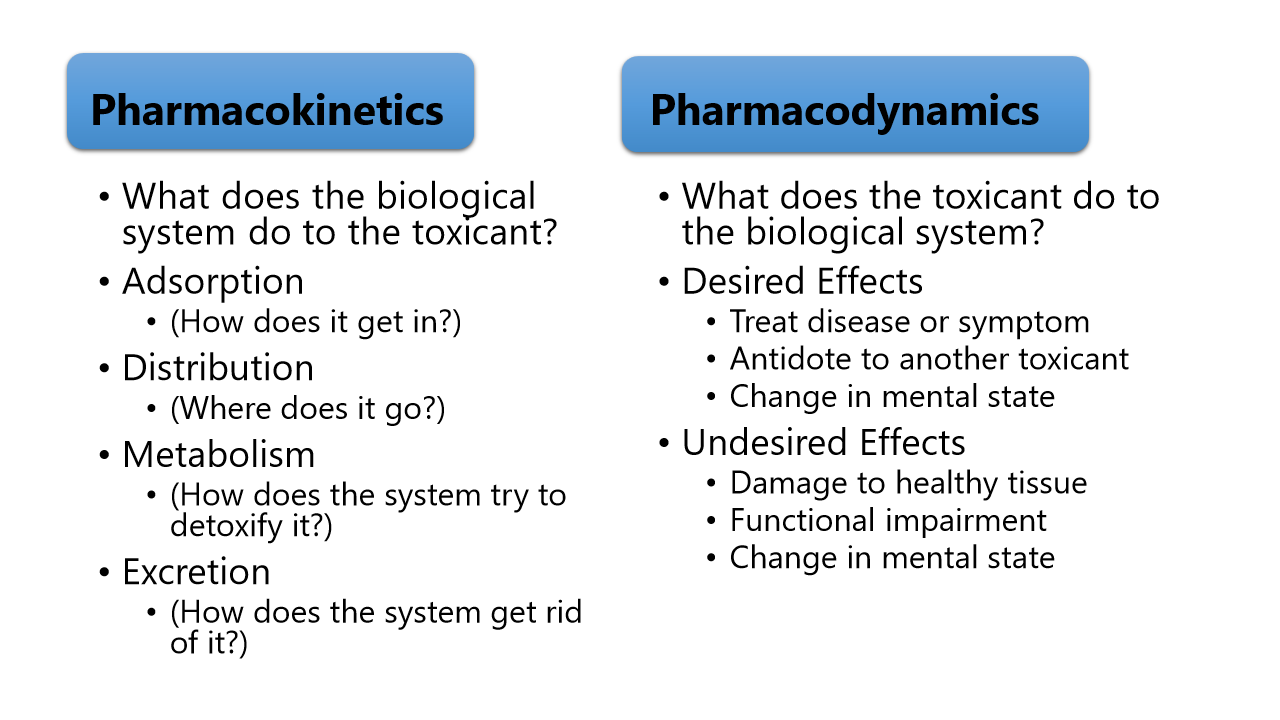

Pharmacokinetics V Pharmacodynamics

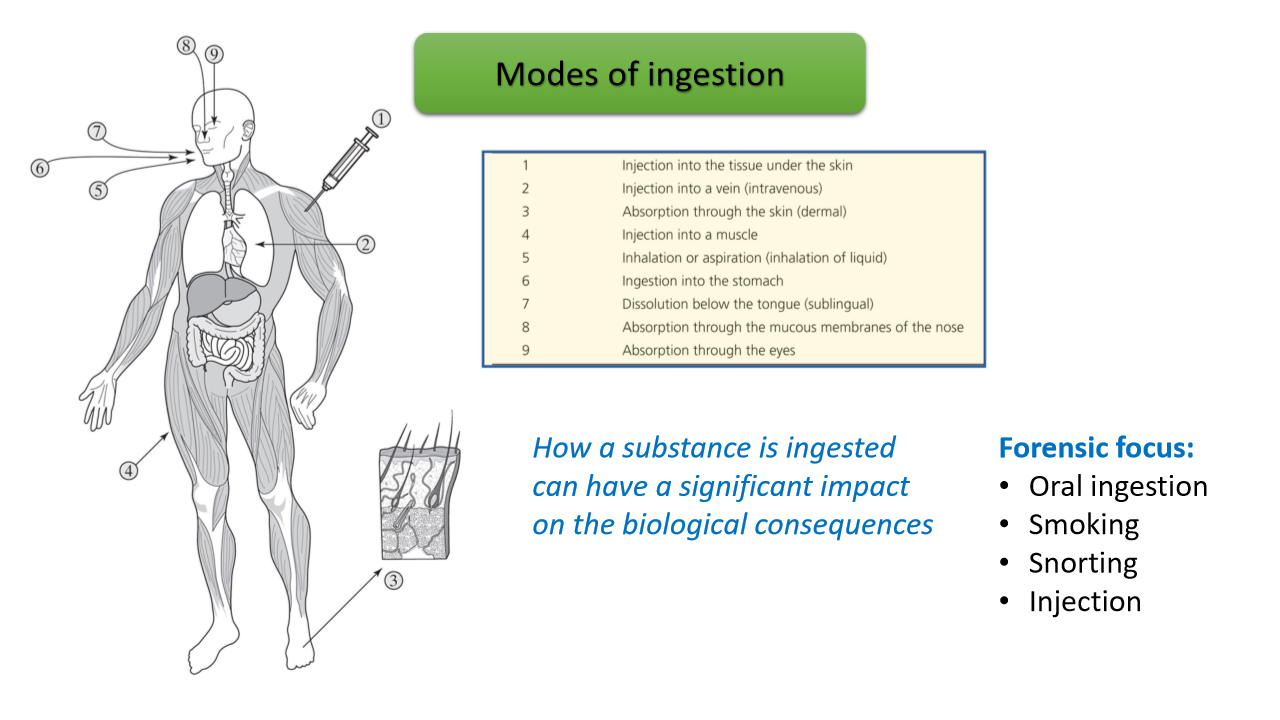

Modes of Ingestion

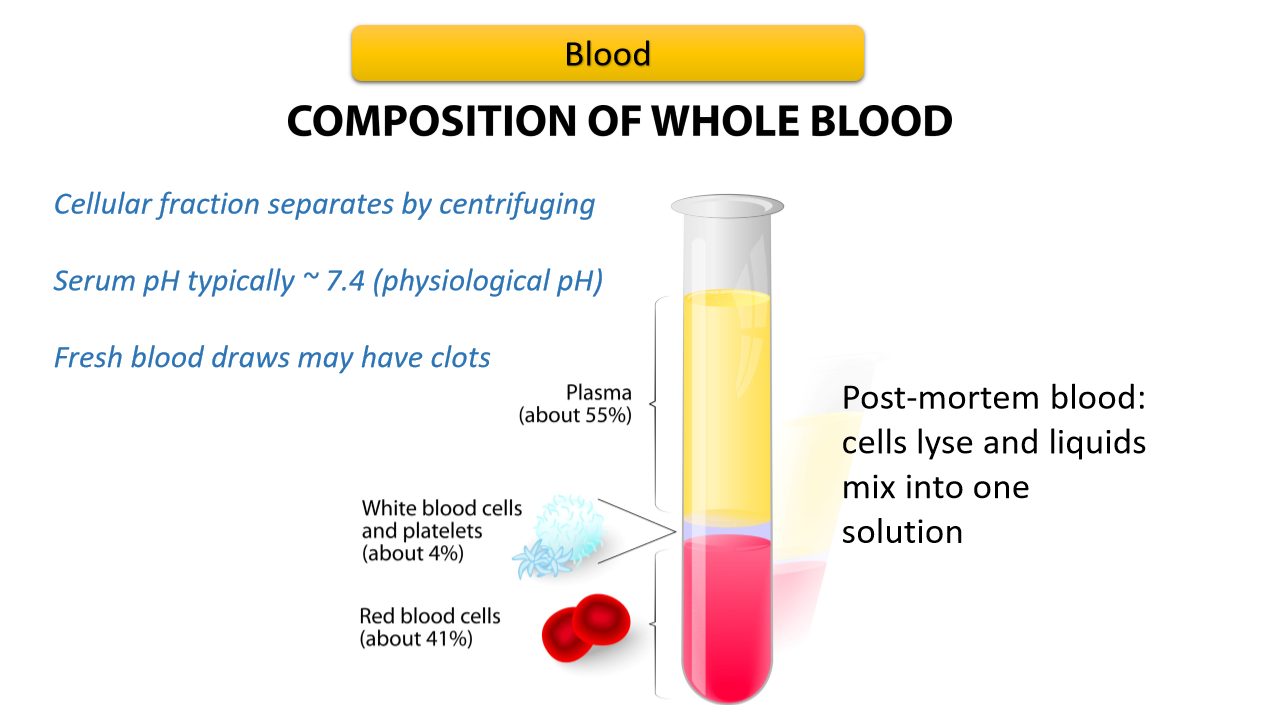

Whole Blood Composition

Urine

Hair

Oral Fluid

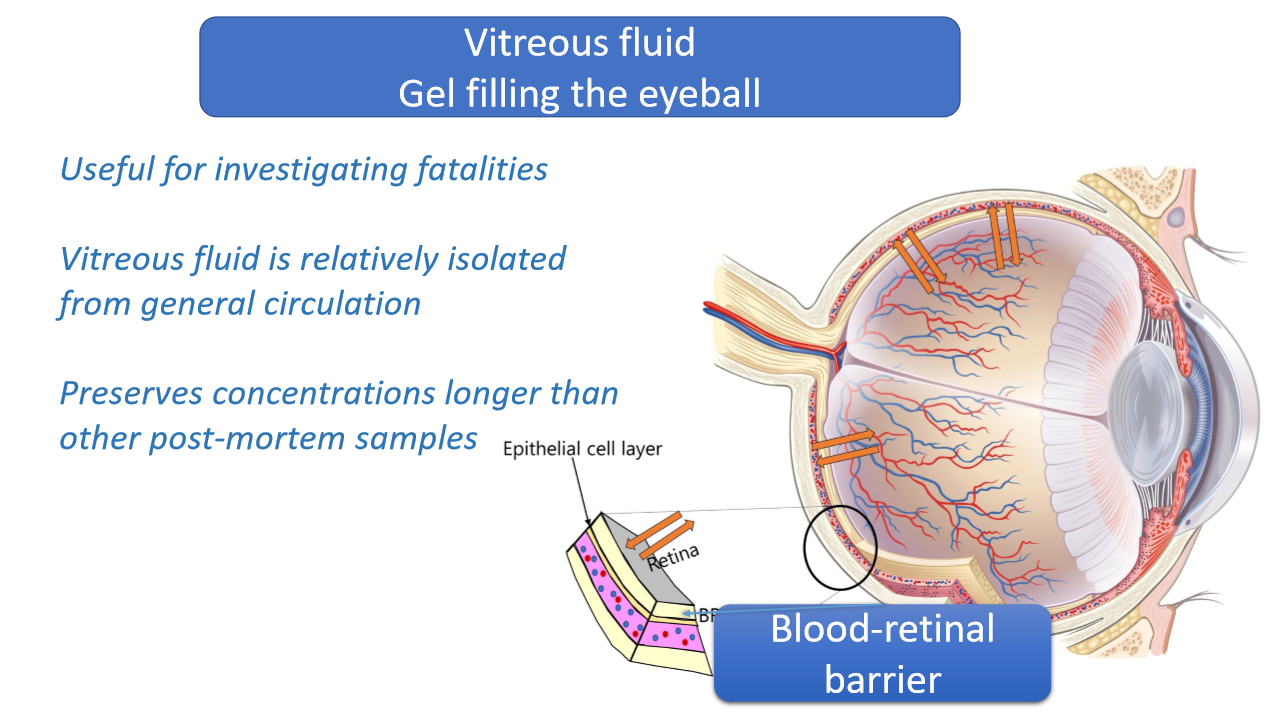

Vitreous

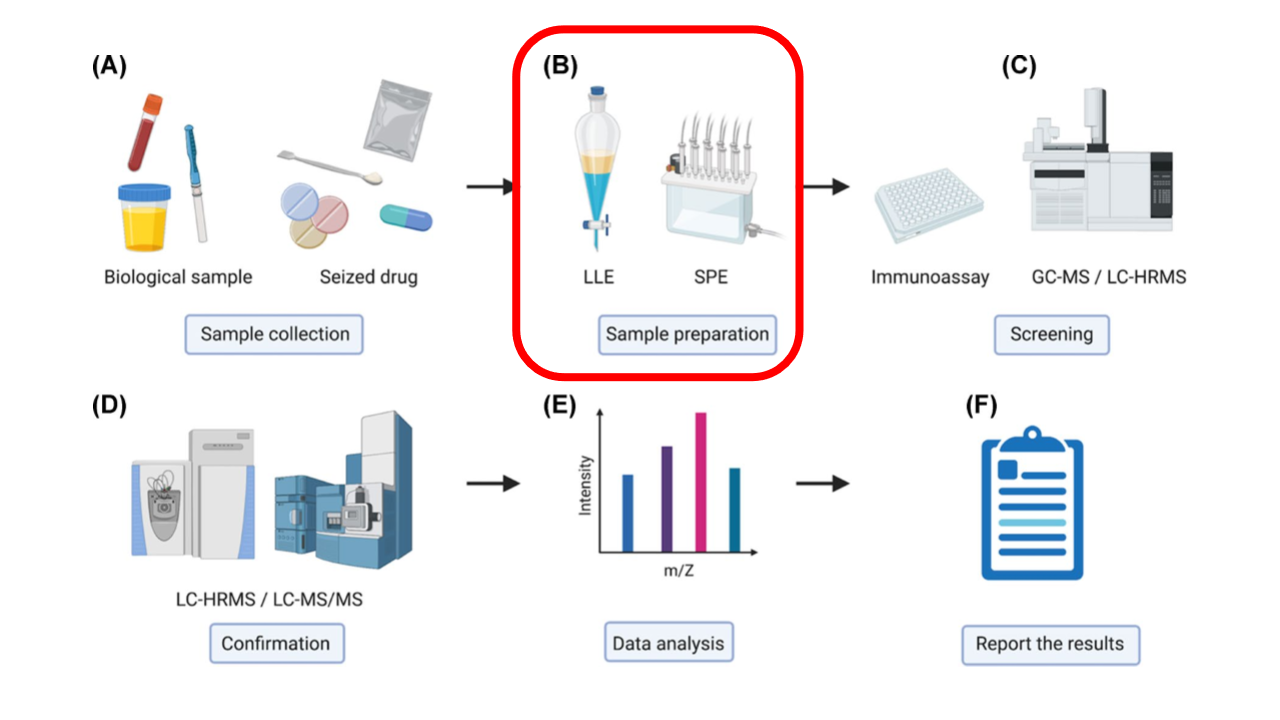

Toxicology 6 steps

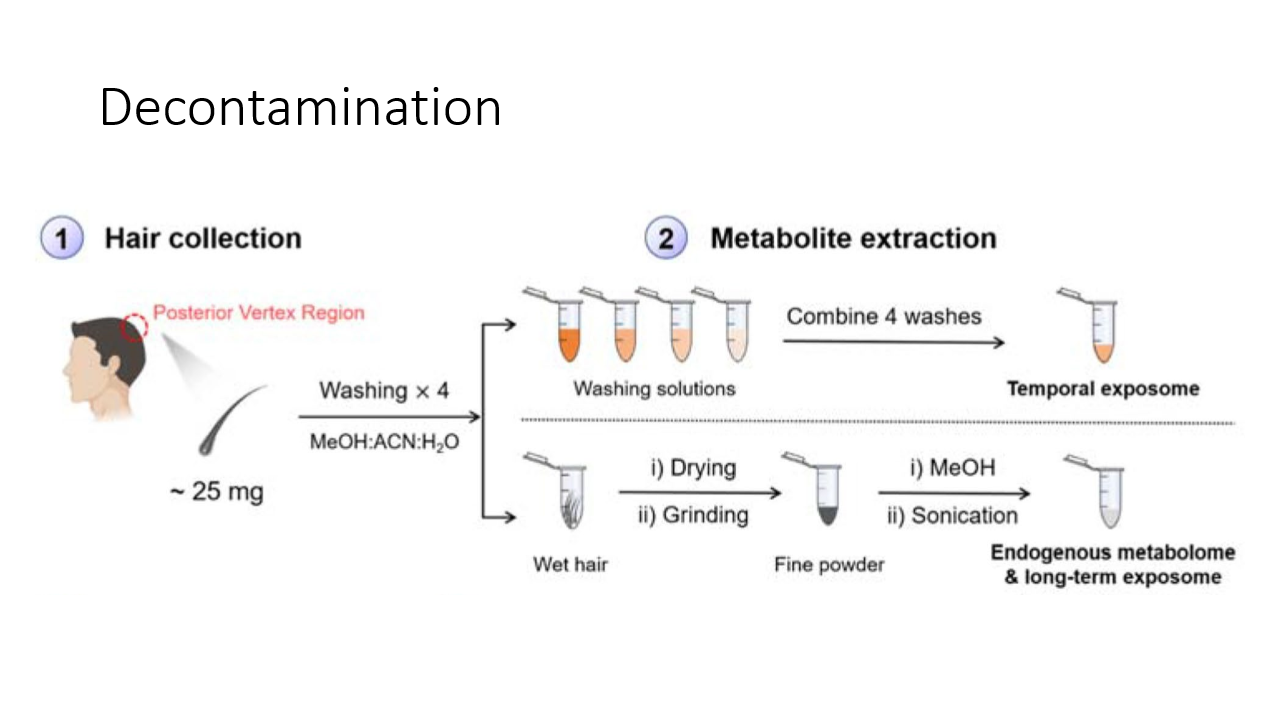

Decontamination

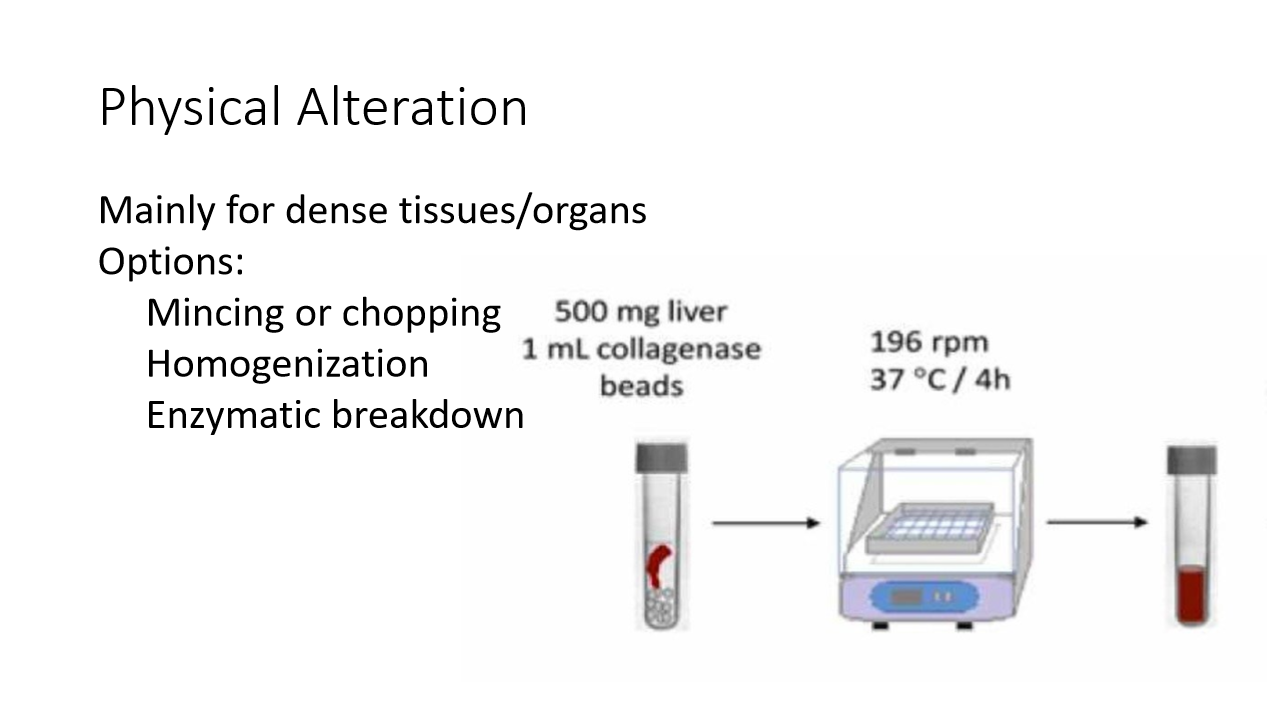

Physical Alteration

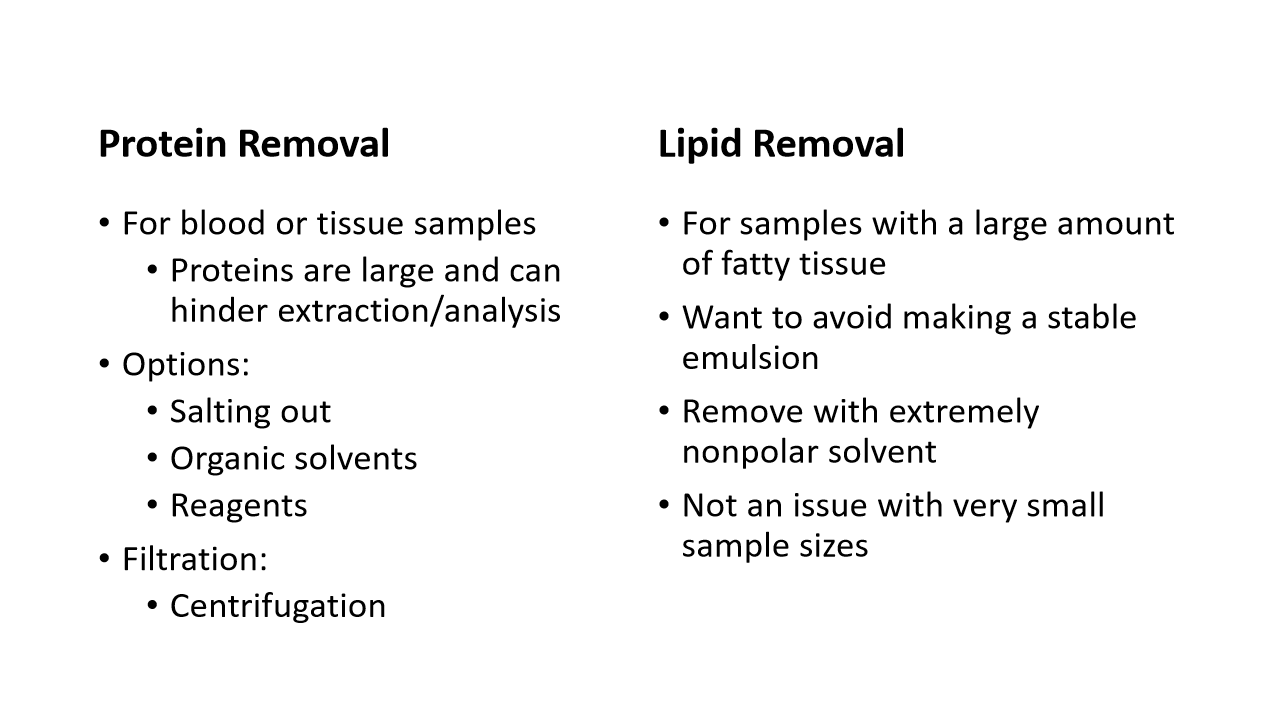

Protein V Lipid Removal

Drug Screening

Immunoassay

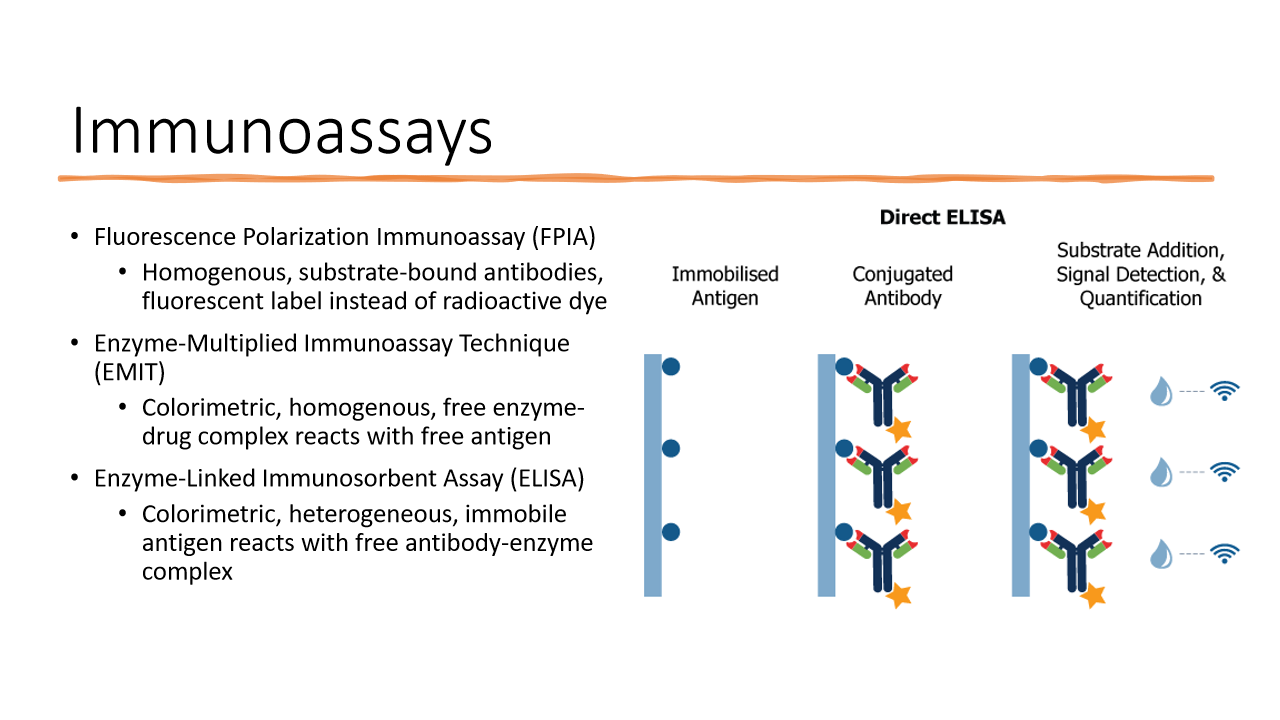

Immunoassay Types

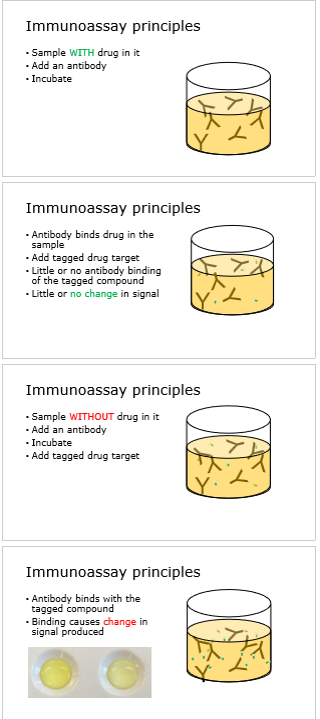

Immunoassay Principles

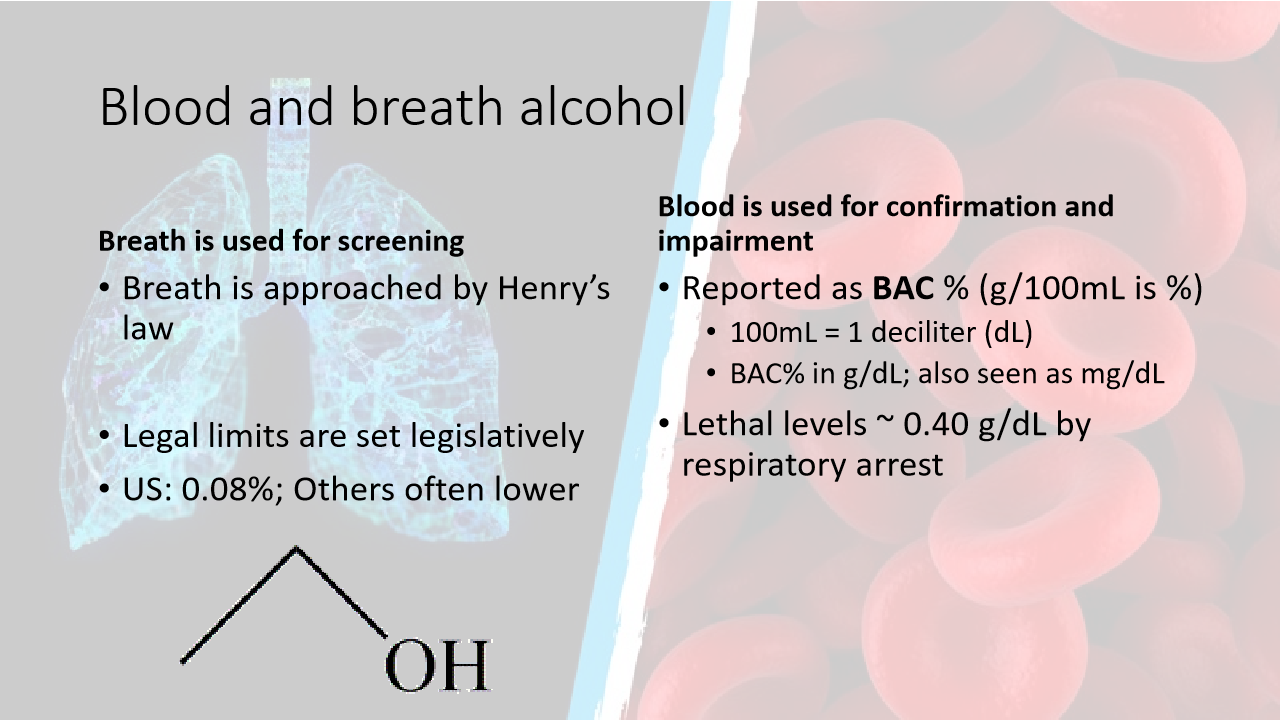

Blood and Breath Alcohol

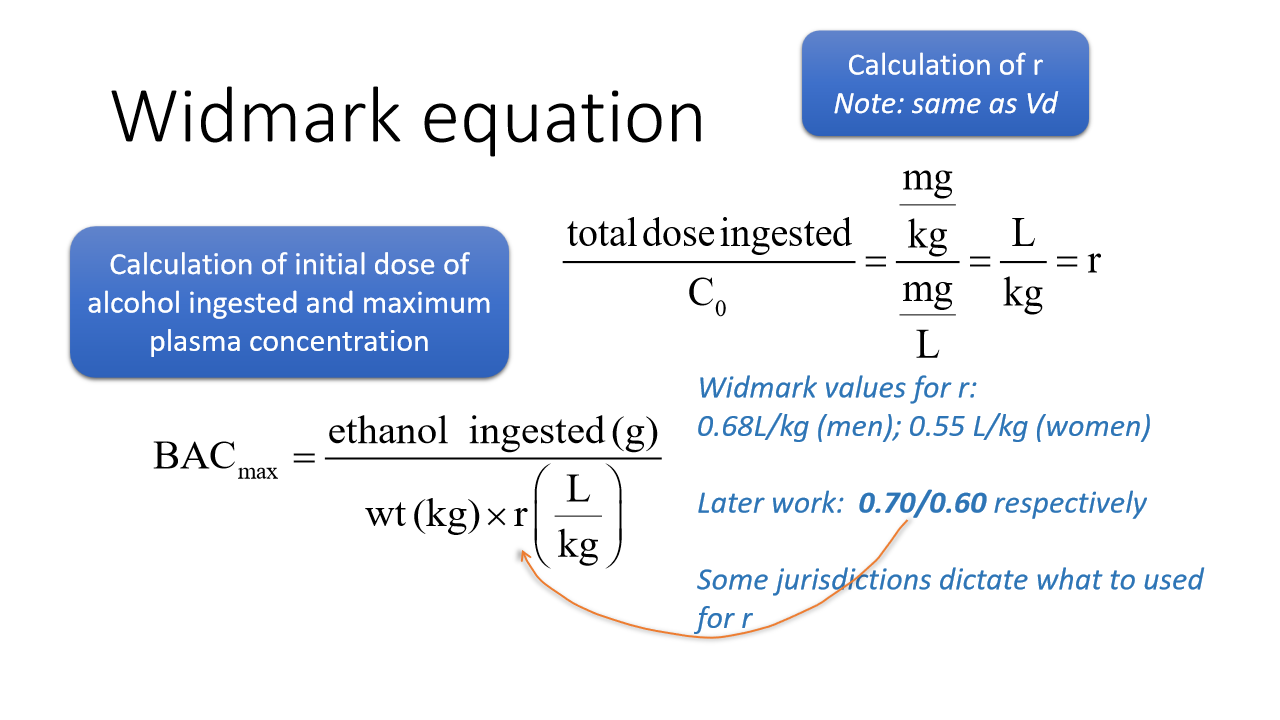

Widemark Equation

Breath Alcohol

Post-Mortem Tox

What you detect from tox depends on (6 things)

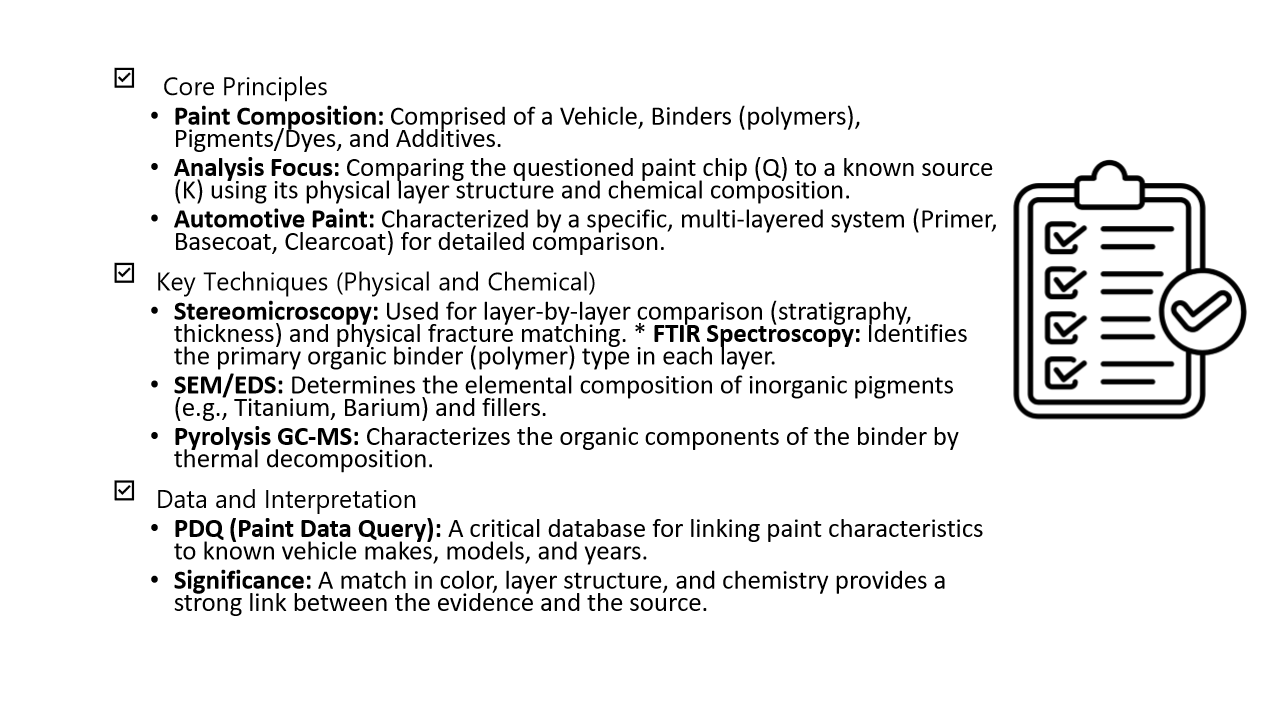

Forensic Paint Analysis

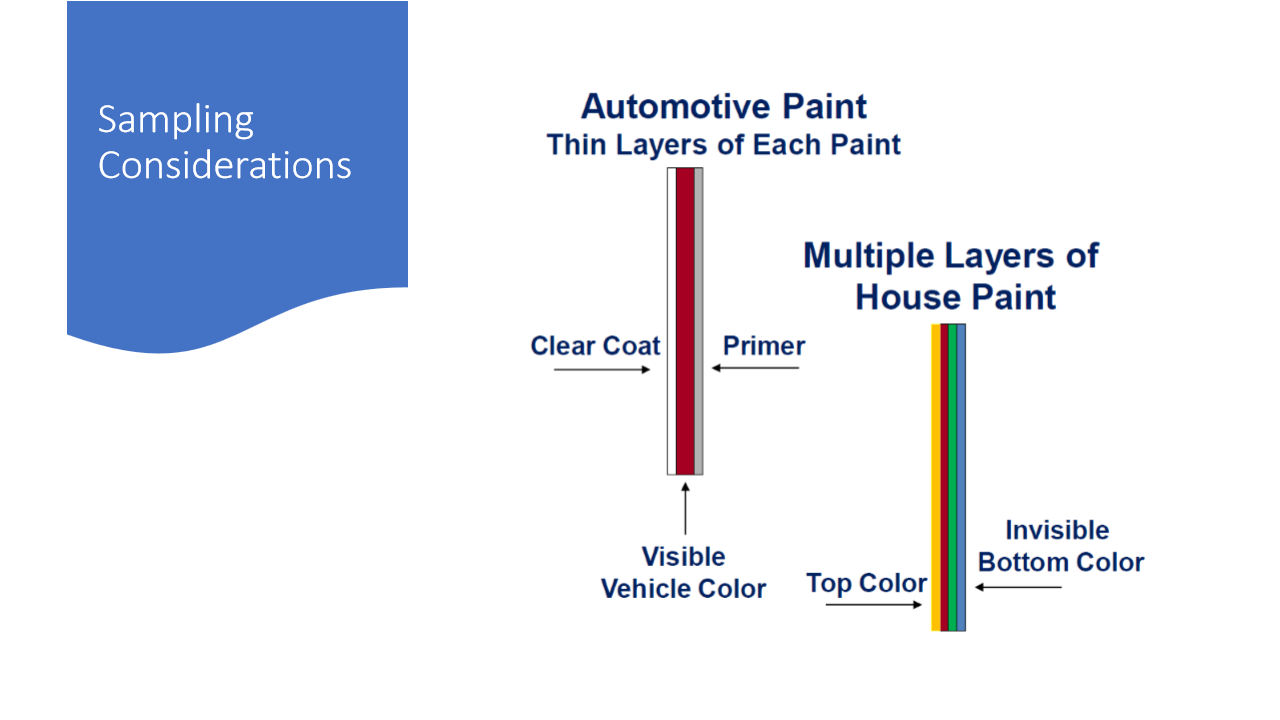

The forensic examination of paint evidence, common in hit-and-run and burglary cases, involves a meticulous comparison of a questioned sample (Q) to a known source (K). The analysis leverages both the physical structure and the chemical composition of the paint.

Vehicle Paint

The liquid portion of a surface coating, minus the pigment, which allows the pigment to be distributed.

Binder

The nonvolatile part of the vehicle that binds pigment particles together. Common binders include polyurethane, epoxy, acrylic, or silicone resins, often cross-linked with melamine or styrene.

Pigments + Dyes

Materials that provide color. Pigments, such as the common white pigment rutile (TiO2), retain a crystalline form, while dyes dissolve in the paint. Extender pigments like barium sulfate and calcite (CaCO3) are used in primers to enhance properties.

Additives

Substances added in small quantities to improve properties, such as driers, corrosion inhibitors, UV absorbers, plasticizers, silicone for scratch resistance, and stabilizers like phthalate.

Enamels V Lacquers

Paint evidence is typically found as chips, which preserve the layer structure, or smears. The film-forming mechanism also differs; enamels involve cross-linking reactions to form a hard, durable surface, while lacquers and latex paints form a film through simple solvent evaporation.

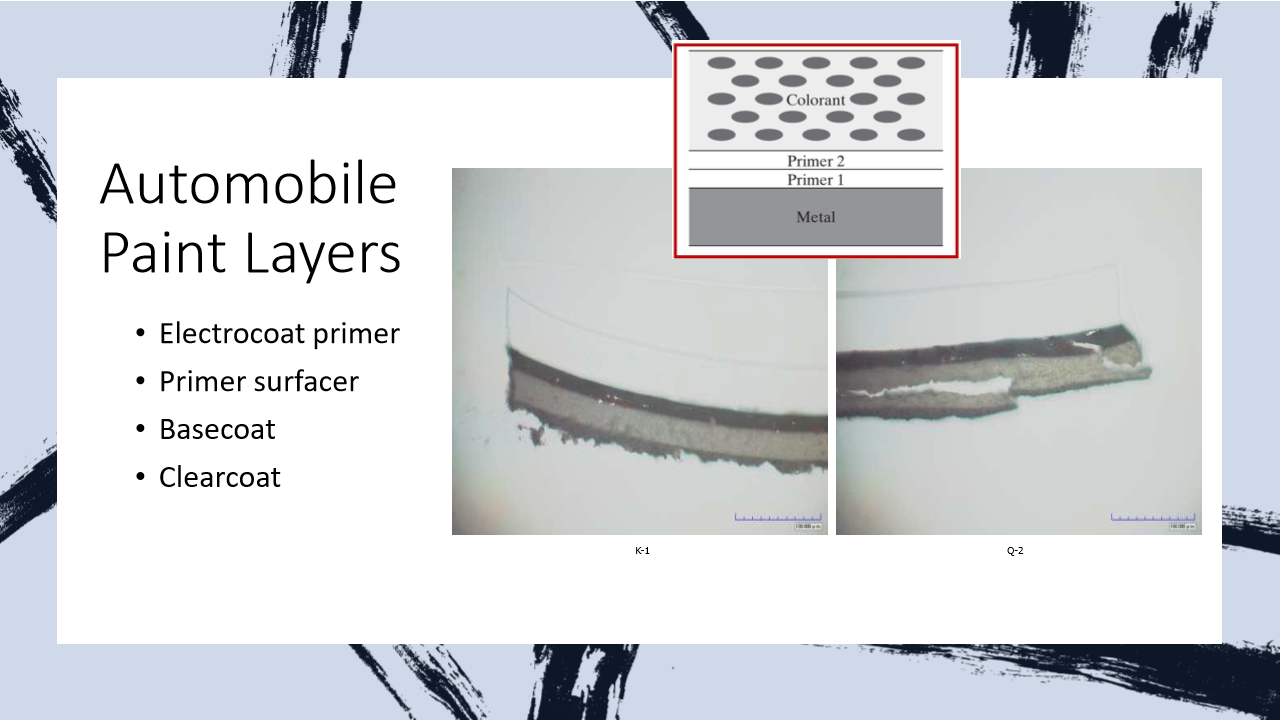

Automotive Paint System + Layers

Automotive paint is of particular forensic significance due to its complex and consistent multi-layer system, which provides numerous points for comparison.

Layers:

Electrocoat Primer

Primer Surfacer

Basecoat

Clearcoat

Electrocoat Primer

The first layer applied to the steel body, providing corrosion resistance.

Primer Surfacer

Applied over the electrocoat to smooth the surface and provide adhesion for the subsequent coats.

Basecoat

Provides the primary color and aesthetic appearance of the vehicle. May contain metallic or pearl pigments.

Clearcoat

An unpigmented top layer that protects the basecoat from UV radiation and environmental damage.

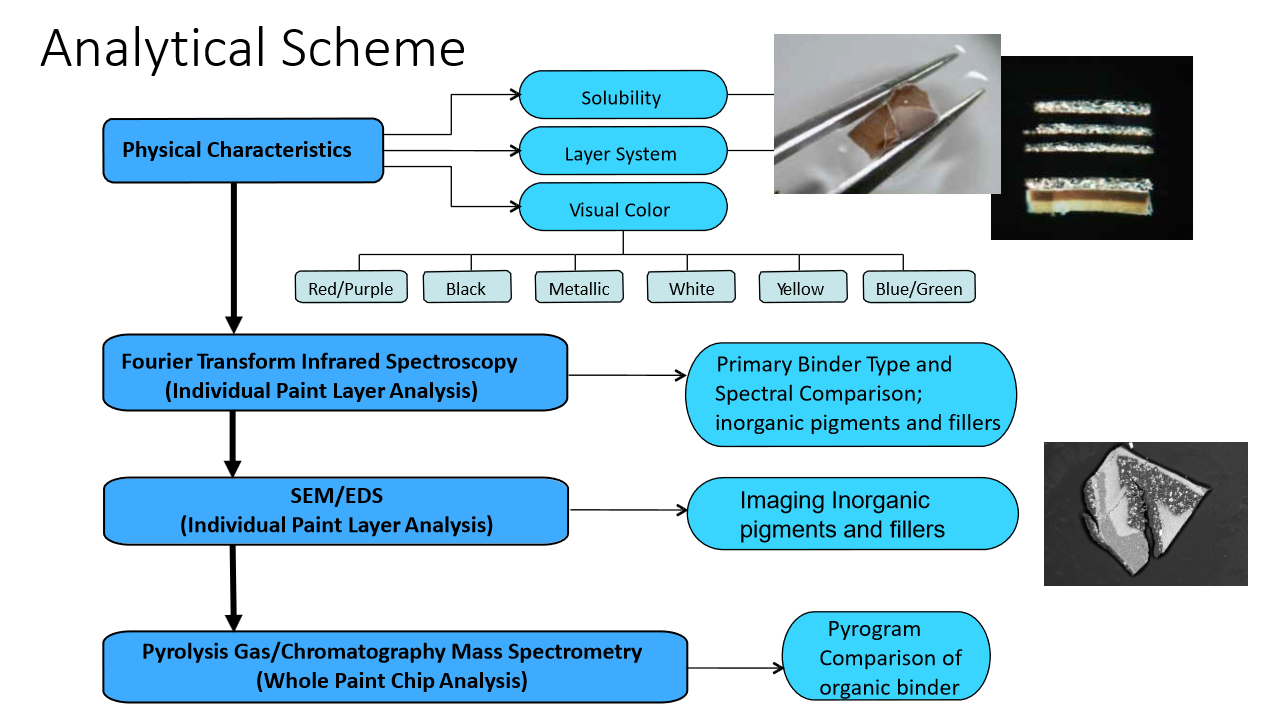

Analytical Scheme Paint Evidence

The analysis of paint evidence follows a structured sequence, moving from physical examination to detailed chemical analysis of each individual layer.

Physical Characteristics (Stereomicroscopy)

Chemical Analysis (Instrumental)

Physical Characteristics (Stereomicroscopy)

Fracture Matching: A physical match of the edges of a paint chip to a known source provides a conclusive link.

Layer Stratigraphy: The sequence, color, and thickness of each layer in the automotive system are compared.

Chemical Analysis (Instrumental)

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Identifies the primary organic binder type (e.g., acrylic, polyurethane) in each layer.

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDS): Provides imaging and determines the elemental composition of inorganic pigments and fillers (e.g., TiO2, BaSO4).

Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC/MS): Characterizes the organic components of the binder by thermally decomposing them and analyzing the resulting fragments.

PDQ Database

The data generated from these analyses is compared to the Paint Data Query (PDQ) database, which contains information on the paint systems used by vehicle manufacturers. A match in color, layer structure, and chemical composition provides a strong association between the evidence and the source.

Forensic Exam of Questioned Docs

A questioned document is any object containing handwritten or printed material whose source or authenticity is in doubt. The examination aims to detect alterations, determine origin, and verify the purported date of preparation through a combination of physical and chemical analyses.

Non-destructive physical analysis

Handwriting Analysis: Compares individual characteristics (e.g., slant, pen pressure, letter formation, loops, "t" crossings) against class characteristics learned from a specific writing system.

Microscopy: Used to assess writing instruments, detect paper coloration, and identify erasures, overwriting, or obliterations.

Indented Writings: Latent impressions on paper are visualized using an Electrostatic Detection Apparatus (ESDA).

Light-Based Methods: Alternate Light Sources (ALS), Infrared (IR), and Ultraviolet (UV) light, often used with a Video Spectral Comparator (VSC), can reveal alterations, differentiate inks, and visualize obliterated text.

Chemical analysis

Ink Composition: Inks consist of colorants (organic dyes or inorganic pigments) and a vehicle, which includes resins (for viscosity) and solvents (e.g., glycols, alcohols, 2-phenoxyethanol in ballpoint pens).

Paper Composition: The paper itself can be analyzed for its fiber composition, pigments, additives, and fillers.

Analytical methods for ink

When chemical analysis is required, a portion of the ink is subjected to a series of tests to create a "chemical fingerprint."

Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC): A primary technique used to separate the individual dye and pigment components of an ink, providing a characteristic pattern for comparison.

Spectroscopy (UV-Vis, FT-IR): These methods help identify the specific chemical compounds, including colorants and vehicle components, present in the ink.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): Provides highly specific identification of the dyes used in an ink formulation.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Can be used to differentiate inks and toners based on the particle size and morphology of their pigments.

Ink Dating and Aging (static V dynamic)

Determining the age of an ink entry is a critical but complex aspect of document examination.

Static Dating: Determines when the ink was manufactured by comparing its formulation to patent records, manufacturer data, and databases of ink tags (fluorescent compounds or rare earth elements added by manufacturers).

Dynamic Dating: Determines when the writing occurred by measuring chemical properties that change over time. A key method involves quantifying the loss of volatile solvents, such as 2-phenoxyethanol (2-PE), from the ink line as it dries on the paper over months and years.

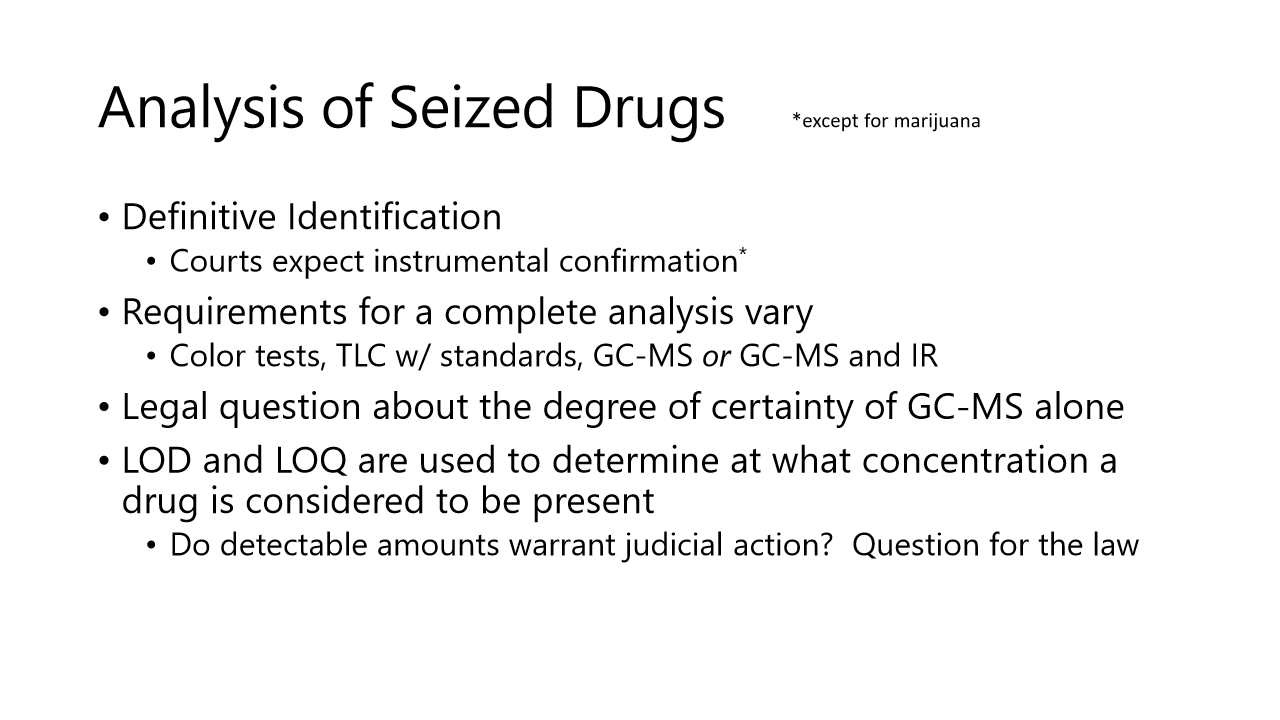

Forensic analysis of illicit drugs

The identification of seized drugs requires a rigorous, systematic analytical scheme to ensure definitive results that can withstand legal scrutiny. The process moves from general, presumptive tests to specific, instrumental confirmation.

Analytical scheme for drugs

The analysis of a suspected drug follows a hierarchical approach, with tests categorized by their specificity. Courts typically require instrumental confirmation (Category A) for a definitive identification, except in the case of marijuana.

Visual Inspection and Classification: The process begins with visual examination, quantity determination, and classification of the substance. Understanding the drug's chemical nature (acidic, basic, neutral) is crucial for selecting appropriate solvents for extraction.

Category C (Screening/Presumptive Tests): These are rapid, inexpensive tests that suggest the presence of a class of drugs but are not specific. They include color tests and immunoassays.

Category B (Selective Tests): These techniques provide more specific information. Examples include the microscopic examination of marijuana for characteristic cystolithic and glandular hairs, and Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) run against known reference standards.

Category A (Confirmatory Tests): These are highly specific instrumental techniques that conclusively identify a substance. Key methods include Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy.

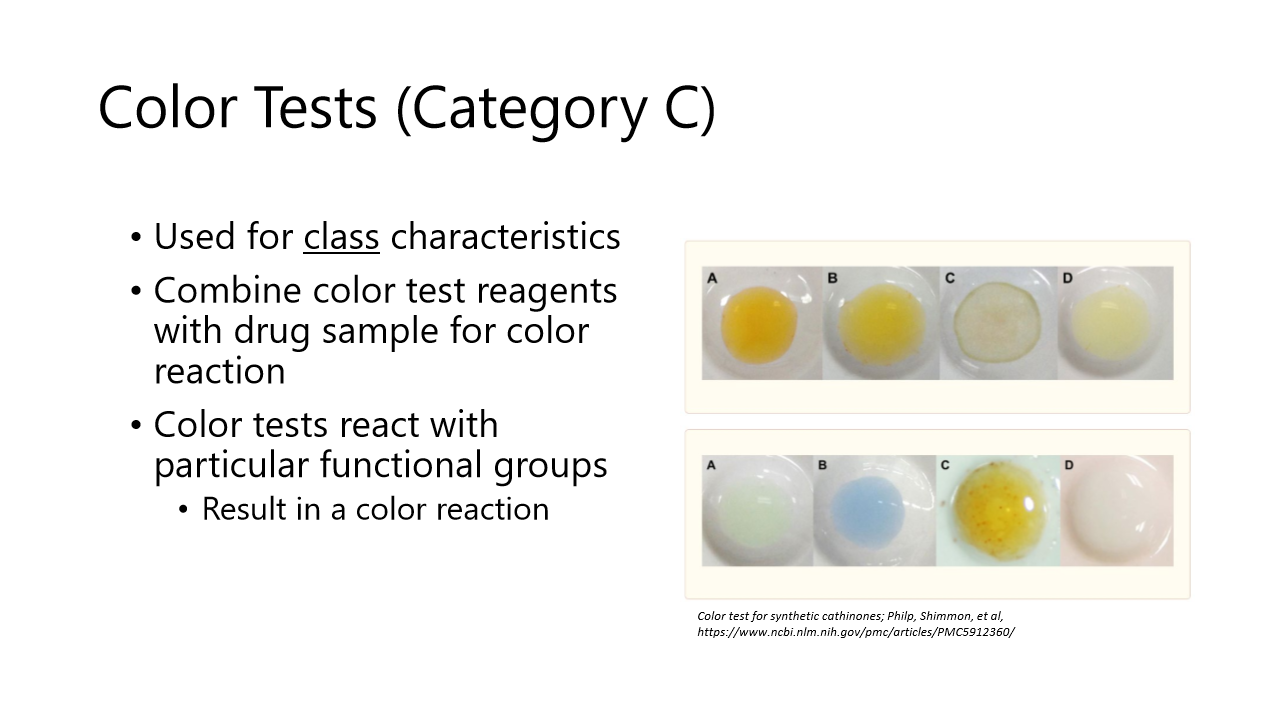

Color Tests

Color tests are a cornerstone of drug screening. They involve adding a specific chemical reagent to a sample, which produces a characteristic color change if certain chemical functional groups are present. While fast, they are prone to false positives.

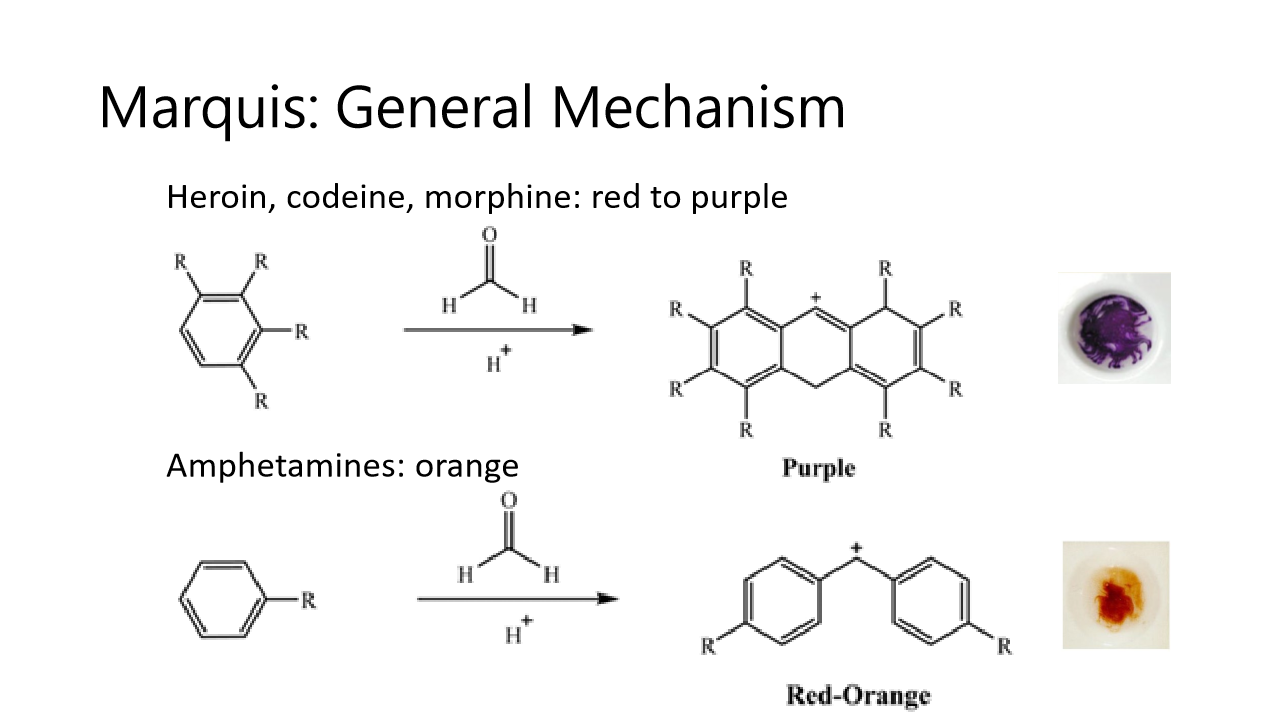

Marquis

General screening. Opiates (Heroin, Morphine): Red to Purple. Amphetamines: Orange.

Mecke

|

Cobalt Thiocyanate

Primarily for cocaine and related compounds (e.g., procaine, lidocaine). Turquoise bottom layer

Mandelin

Popular for identifying Ketamine (Reddish-Orange).

Duquenois Levine

Specific for THC in marijuana. A positive test results in a purple color in the final chloroform layer.

NPS Challenges

The emergence of NPS, such as synthetic cathinones ("bath salts") and synthetic cannabinoids, presents an ongoing challenge. These designer drugs are structurally related to controlled substances but are modified to evade existing laws, requiring forensic labs to constantly adapt and develop new analytical procedures for their detection and identification.

Principles of forensic tox

Forensic toxicology involves the identification and quantification of drugs, alcohol, and other foreign substances (xenobiotics) in biological samples to aid in legal investigations concerning criminal law violations or manner of death.

Pharmacokinetics V Pharmacodynamics

Interpreting toxicological results requires a fundamental understanding of how a substance moves through the body (pharmacokinetics) and its effect on the body (pharmacodynamics).

Pharmacokinetics ADME

Absorption: The process by which a substance enters the bloodstream. The route (oral, injection, smoking) significantly impacts the speed of onset and the amount of drug that reaches target tissues (bioavailability).

Distribution: The movement of the substance throughout the body's tissues and fluids.

Metabolism: The chemical transformation of the substance by the body, primarily in the liver, into metabolites that are easier to eliminate.

Excretion: The removal of the substance and its metabolites from the body, typically via urine.

Pharmacodynamics

Describes the effects of the toxicant on the biological system, which can be desired (therapeutic) or undesired (impairment, tissue damage).

Blood

The primary sample for determining impairment. Post-mortem collection distinguishes central (heart) from peripheral (femoral) blood.

Urine

Detects recent drug use; drug and metabolite concentrations are often higher than in blood but do not directly correlate with impairment.

Vitreous

The gel filling the eyeball. It is relatively isolated and can preserve substance concentrations longer in post-mortem cases.