15 - halogen compounds

1/24

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

25 Terms

halogenoalkanes

alkanes that have one or more halogens

They can be produced from:

Free-radical substitution of alkanes

Electrophilic addition of alkenes

Substitution of an alcohol

free radical substitution of alkenes to produce halogenoalkanes

A free-radical substitution reaction involves three main steps: initiation, propagation, and termination

This reaction occurs between an alkane and a halogen, such as chlorine (Cl2) or bromine (Br2), in the presence of ultraviolet (UV) light

Initiation:

UV light provides energy to break the Cl–Cl or Br–Br bond by homolytic fission, producing two identical halogen free radicals (Cl• or Br•)

Propagation:

The halogen radicals react with alkane molecules in a chain reaction, producing new radicals and continuing the substitution of hydrogen atoms with halogen atoms

Termination:

The reaction stops when two free radicals combine to form a stable molecule, ending the chain process

Free-radical substitution reactions of alkanes

electrophilic addition to produce halogenoalkanes

Halogenoalkanes can also be produced from the addition of hydrogen halides(HX) or halogens (X2) at room temperature to alkenes

In hydrogen halides, the hydrogen acts as the electrophile and accepts a pair of electrons from the C-C bond in the alkene

The major product is the one in which the halide is bonded to the most substituted carbon atom (Markovnikov’s rule)

In the addition of halogens to alkenes, one of the halogen atoms acts as an electrophile and the other as a nucleophile

Electrophilic addition to alkenes

substitution of alcohols to produce a halogenoalkane

In the substitution of alcohols an alcohol group is replaced by a halogen to form a halogenoalkane

The substitution of the alcohol group for a halogen can be achieved by reacting the alcohol with:

HX (or KBr with H2SO4 or H3PO4 to make HX)

PCl3 and heat

PCl5 at room temperature

SOCl2

Substitution of alcohols

Substitution of alcohols produces halogenoalkanesDifferent methods of forming halogenoalkanes

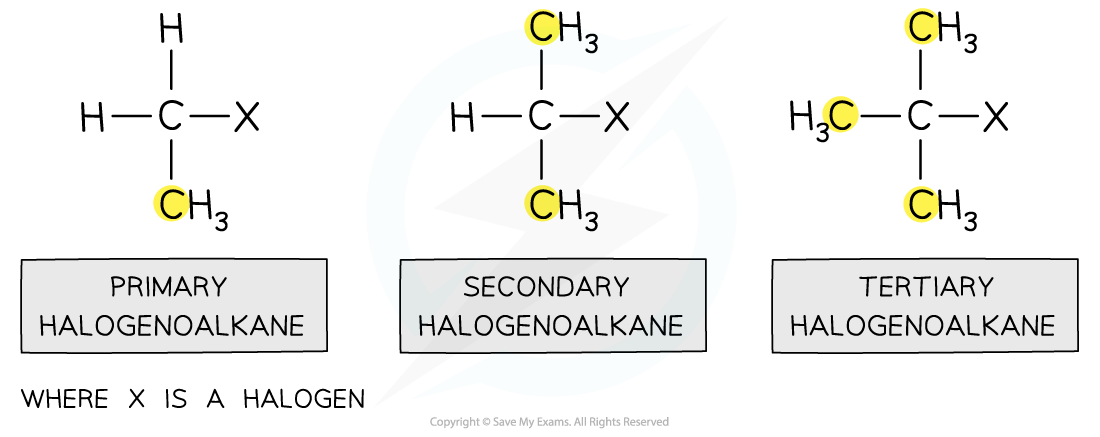

classifying halogenoalkanes

Depending on the carbon atom the halogen is attached to, halogenoalkanes can be classified as primary, secondary and tertiary

A primary halogenoalkane is when a halogen is attached to a carbon that itself is attached to one other alkyl group

A secondary halogenoalkane is when a halogen is attached to a carbon that itself is attached to two other alkyl groups

A tertiary halogenoalkane is when a halogen is attached to a carbon that itself is attached to three other alkyl groups

nucleophilic substituion of halogenoalkanes

Halogenoalkanes are much more reactive than alkanes due to the presence of the electronegative halogens

The halogen-carbon bond is polar causing the carbon to carry a partial positive and the halogen a partial negative charge

A nucleophilic substitution reaction is one in which a nucleophile attacks a carbon atom which carries a partial positive charge

An atom that has a partial negative charge is replaced by the nucleophile

Explaining the polarity of a carbon-halogen bond

halogenoalkane reaction with an aqueous alkali - NaOH

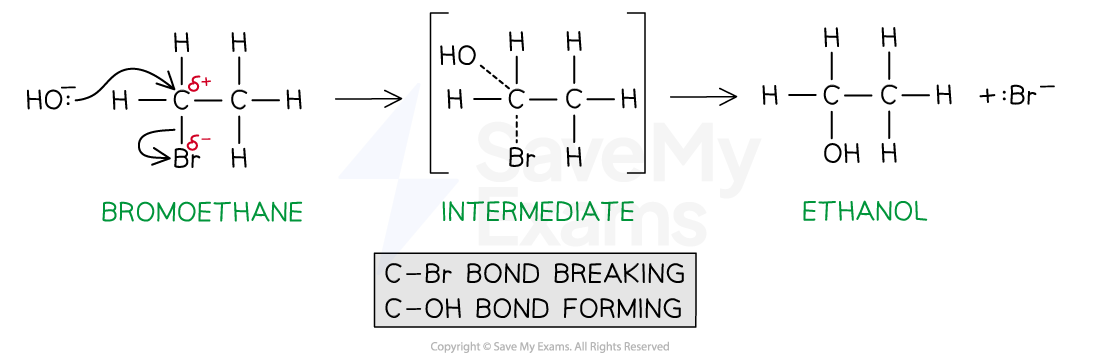

The reaction of a halogenoalkane with aqueous alkali results in the formation of an alcohol

The halogen is replaced by the OH-

The aqueous hydroxide (OH- ion) behaves as a nucleophile by donating a pair of electrons to the carbon atom bonded to the halogen

For example, bromoethane reacts with aqueous alkali when heated (under reflux (?)) to form ethanol

Hence, this reaction is a nucleophilic substitution

The halogen is replaced by a nucleophile, :OH–

CH3CH2Br + :OH– → CH3CH2OH + :Br–

reaction of a halogenoalkane with KCN

The nucleophile in this reaction is the cyanide, CN- ion

Ethanolic solution of potassium cyanide (KCN in ethanol) is heated under reflux with the halogenoalkane

The product is a nitrile

For example, bromoethane reacts with ethanolic potassium cyanide when heated under reflux to form propanenitrile

The halogen is replaced by a nucleophile, :CN–

CH3CH2Br + :CN– → CH3CH2CN + :Br–

The nucleophilic substitution of halogenoalkanes with KCN adds an extra carbon atom to the carbon chain

This reaction can therefore be used by chemists to make a compound with one more carbon atom than the best available organic starting material

reaction of a halogenoalkane with NH3

The nucleophile in this reaction is the ammonia, NH3 molecule

An ethanolic solution of excess ammonia (NH3 in ethanol) is heated under pressure with the halogenoalkane

⚙ Mechanism (Step-by-step explanation):🧪 Step 1: Nucleophilic attack

The lone pair on ammonia (NH₃) attacks the δ⁺ carbon of the haloalkane (e.g. bromoethane: CH₃CH₂Br), where the C-Br bond is polar.

This leads to the substitution of the bromine atom (Br⁻), and you get a positively charged intermediate (Usually, when a nitrogen atom forms an extra, 4th bond, it uses its lone pair of electrons to form a co-ordinate, dative covalent bond to the other atom it is bonding to. Now, once this co-ordinate bond forms, one of the electrons in the bond can now be thought of as 'belonging' to the new atom the nitrogen has bonded to, and one as belonging to the nitrogen. From this, the nitrogen atom would end up with a positive charge as it can be considered as having 'lost' an electron.):

CH3CH2Br + NH3→CH3CH2NH3+ + Br−

🧪 Step 2: Deprotonation

A second molecule of ammonia acts as a base. It removes a proton (H⁺) from the intermediate (CH₃CH₂NH₃⁺), giving:

CH3CH2NH3+ + NH3→CH3CH2NH2 + NH4

Final products:

Primary amine: CH₃CH₂NH₂ (ethylamine)

Ammonium ion: NH₄⁺. +. Halide ion: Br⁻ = ammonium halide salt (ionic)

❗ Why excess ammonia is needed:

The amine product (CH₃CH₂NH₂) has a lone pair on the nitrogen (during deprotonation, N accepts pair of e-) — it can also act as a nucleophile and attack another molecule of haloalkane, forming:

Secondary amine: CH₃CH₂NHCH₂CH₃ (diethylamine)

Then it can go further to tertiary and quaternary amines if more haloalkane is present.

➡ To reduce this happening and get mostly primary amine, we use excess ammonia so that ammonia outcompetes the amine as the nucleophile.

🔁 Overall balanced equation:CH3CH2Br+2NH3→CH3CH2NH2+NH4BrCH3CH2Br+2NH3→CH3CH2NH2+NH4Br

reaction of a halogenoalkane with aqueuous silver nitrate

Halogenoalkanes can be broken down under reflux by water to form alcohols

The breakdown of a substance by water is also called hydrolysis

The water in aqueous silver nitrate will hydrolyse the halogenoalkane

The fastest nucleophilic substitution reactions take place with the iodoalkanes as the C-I bond is the weakest (longest) - because iodine has the largest radius so poor atomic orbital overlap to form a strong bond

The slowest nucleophilic substitution reactions take place with the fluoroalkanes as the bond is the strongest (shortest)

For example, bromoethane reacts with aqueous silver nitrate solution to form ethanol and a Br- ion

The Br- ion will form a cream precipitate with Ag+

This reaction is classified as a nucleophilic substitution reaction with water molecules in aqueous silver nitrate solution acting as nucleophiles, replacing the halogen in the halogenoalkane

C2H5Br + OH- → (reflux) C2H5OH + Br-

Nucleophilic substitution with OH–

nucleophilic substitution of a halogenoalkane with OH-

This reaction is similar to the nucleophilic substitution reaction of halogenoalkanes with aqueous alkali, however, hydrolysis with water is much slower than with the OH- ion in alkalis

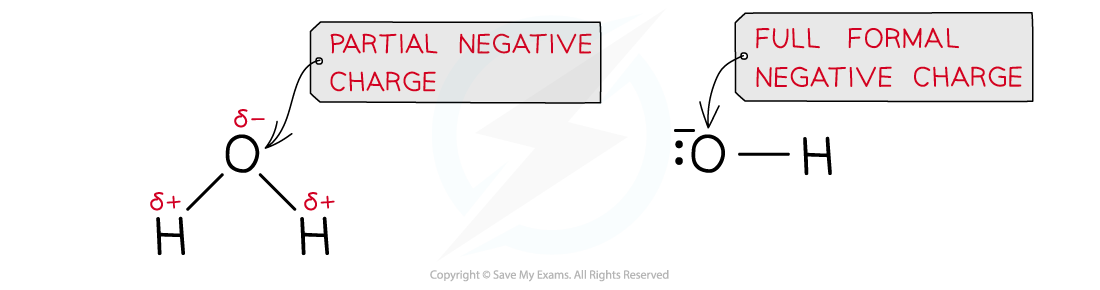

The hydroxide ion is a better nucleophile than water as it carries a full formal negative charge

In water, the oxygen atom only carries a partial negative charge

Step-by-step (SN2 mechanism for primary halogenoalkanes):

The lone pair on the hydroxide ion (OH⁻) acts as a nucleophile (electron-pair donor).

It attacks the δ⁺ carbon that's bonded to the halogen (Br, Cl, or I) in the halogenoalkane.

At the same time, the C–Br bond breaks heterolytically, and the Br⁻ leaves (as a leaving group).

This forms a new C–OH bond, creating an alcohol.

🌀 This is a one-step reaction (for primary halogenoalkanes) called SN2:

water vs hydroxide ions as nucleophiles

A hydroxide ion is a better nucleophile as it has a full formal negative charge whereas the oxygen atom in water only carries a partial negative charge; this causes the nucleophilic substitution reaction with water to be much slower than with aqueous alkali

The halogenoalkanes have different rates of hydrolysis

This reaction can be used as a test to identify halogens in a halogenoalkane by measuring how long it takes for the test tubes containing the halogenoalkane and aqueous silver nitrate solutions to become opaque

🔹 1. Nucleophilicity (how strong they are as nucleophiles)

Species | Nucleophilicity | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

OH⁻ | Strong nucleophile | It has a full negative charge and a lone pair on oxygen → more electron-rich, so it's more reactive. |

H₂O | Weak nucleophile | It’s neutral and has lone pairs on oxygen, but less reactive because there’s no negative charge pushing it to donate electrons. |

🔹 2. Mechanism and Reactivity

OH⁻ reacts faster in nucleophilic substitution reactions than H₂O.

H₂O can still act as a nucleophile, especially with more reactive substrates like tertiary halogenoalkanes, but the reaction is slower.

🔹 4. Conditions

Reagent | Typical Conditions |

|---|---|

OH⁻ | Aqueous NaOH or KOH, warm/reflux |

H₂O | Excess water or moist conditions, often with heating |

both heated under reflux

elimination reactions of halogenoalkanes

An elimination reaction involves the loss of a small molecule from a larger organic molecule

In halogenoalkanes, this small molecule is usually a hydrogen halide (e.g. HBr or HCl)

The product is typically an alkene

The elimination reaction of bromoethane with ethanolic sodium hydroxide

OH⁻ acts as a base mainly in elimination reactions, where it removes a proton (H⁺) from a molecule instead of attacking the carbon directly.

For example, in an elimination reaction of a halogenoalkane to form an alkene, OH⁻ abstracts a hydrogen atom from the carbon adjacent (the beta carbon) to the carbon bonded to the halogen.

Additionally, when OH⁻ reacts with an alcohol, it can remove the acidic hydrogen (H⁺) from the –OH group of the alcohol, forming an alkoxide ion.

The alkoxide ion is a stronger base than OH⁻ itself, due to the electron-donating inductive effect of the alkyl group, and it is also sterically bulkier.

Because of this, the alkoxide ion is less likely to act as a nucleophile and more likely to act as a base, removing β-hydrogens and promoting elimination reactions.

reaction conditions for elimination

Halogenoalkanes are heated with ethanolic sodium hydroxide (NaOH dissolved in ethanol)

Under these anhydrous conditions, elimination occurs:

The C–X bond (where X = halogen) breaks heterolytically

A halide ion (X⁻) is released

A double bond forms, producing an alkene

E.g. Elimination of bromoethane:

bromoethane + sodium hydroxide (ethanol) → ethene + sodium bromide + water

C2H5Br + NaOH (ethanol) → C2H4 + NaBr + H2O

One hydrogen atom and the bromine atom are eliminated

The carbon chain forms a C=C double bond to make ethene

examiner tips and tricks - elimination vs substitution

Reaction conditions are crucial in determining the product.

Elimination = hot, ethanolic NaOH

Substitution = warm, aqueous NaOH

+ in elimination, OH- acts as a base and in nucleophilic substitution it acts as a nucleophile.

👀 Key Differences Summary

Feature | Substitution (SN1/SN2) | Elimination (E1/E2) |

|---|---|---|

Type of reagent | Nucleophile | Base |

Major product | Alcohol / nitrile / amine etc. | Alkene |

Preferred halogenoalkanes | SN1: tertiary | E1: tertiary |

Solvent | Aqueous | Ethanolic |

Temperature | Lower (20–50 °C) | Higher (>70 °C) |

OH⁻ role | Nucleophile | Base |

Stereochemistry (SN2) | Inversion of configuration | No stereochemistry |

Competition | Both can happen simultaneously | Products depend on exact conditions |

SN1 and SN2 brief overview

In nucleophilic substitution reactions involving halogenoalkanes, the halogen atom is replaced by a nucleophile

These reactions can occur in two different ways (known as SN2 and SN1 reactions) depending on the structure of the halogenoalkane involved

SN2 reactions

n primary halogenoalkanes, the carbon that is attached to the halogen is bonded to one alkyl group

These halogenoalkanes undergo nucleophilic substitution by an SN2 mechanism

‘S’ stands for ‘substitution’

‘N’ stands for ‘nucleophilic’

‘2’ means that the rate of the reaction (which is determined by the slowest step of the reaction) depends on the concentration of both the halogenoalkane and the nucleophile ions

Both the haloalkane (R–X) and the nucleophile (Nu⁻) take part in the same, single step, so the reaction is bimolecular(involves two molecules colliding at once).

Defining an SN2 mechanism

Each term in the SN2 expression has a specific meaning

The SN2 mechanism is a one-step reaction

The nucleophile donates a pair of electrons to the δ+ carbon atom to form a new bond

At the same time, the C-X bond is breaking and the halogen (X) takes both electrons in the bond (heterolytic fission)

The halogen leaves the halogenoalkane as an X- ion

For example, the nucleophilic substitution of bromoethane by hydroxide ions to form ethanol

SN1 reactions

In tertiary halogenoalkanes, the carbon that is attached to the halogen is bonded to three alkyl groups

These halogenoalkanes undergo nucleophilic substitution by an SN1 mechanism

‘S’ stands for ‘substitution’

‘N’ stands for ‘nucleophilic’

‘1’ means that the rate of the reaction (which is determined by the slowest step of the reaction) depends on the concentration of only one reagent, the halogenoalkane

Defining an SN1 mechanism

Each term in the SN1 expression has a specific meaning

The SN1 mechanism is a two-step reaction

In the first step, the C-X bond breaks heterolytically and the halogen leaves the halogenoalkane as an X- ion (this is the slow and rate-determining step)

This forms a tertiary carbocation (which is a tertiary carbon atom with a positive charge)

In the second step, the tertiary carbocation is attacked by the nucleophile

For example, the nucleophilic substitution of 2-bromo-2-methylpropane by hydroxide ions to form 2-methyl-2-propanol

The nucleophilic substitution of 2-bromo-2-methylpropane by hydroxide ions

In this mechanism, the 2-bromo-2-methylpropane is a tertiary halogenoalkane

which carbocations undergo which mechanism

tertiary undergo SN1

primary undergo SN2

Secondary halogenoalkanes undergo a mixture of both SN1 and SN2 reactions depending on their structure

explain the differences between SN1 and SN2 reactions

🔥 WHY STABILITY DETERMINES SN1 vs SN2🧪 In SN1, the reaction depends on the carbocation forming first:

Step 1: The C–Br bond breaks on its own, forming a carbocation (C⁺).

This step is slow and is the rate-determining step.

So — SN1 can only happen if that carbocation is stable enough to form and survive.

💡 What makes a carbocation stable?

Tertiary carbocations are the most stable, because:

The 3 alkyl groups around the positive carbon donate electrons (inductive effect).

They stabilise the charge by spreading it out.

Primary carbocations are very unstable, so they almost never form.

👉 Therefore:

Tertiary halogenoalkanes → undergo SN1 (stable carbocation can form)

Primary halogenoalkanes → can’t form stable carbocations → so SN1 doesn’t happen

⚡ In SN2, no carbocation forms:

The nucleophile attacks at the same time the halide leaves.

This works best when the carbon isn’t crowded.

So SN2 happens with primary halogenoalkanes, where the carbon is easier to access.

Feature

SN1 (Unimolecular)

SN2 (Bimolecular)

Full name

Substitution Nucleophilic Unimolecular

Substitution Nucleophilic Bimolecular

Steps

Two-step mechanism

One-step mechanism

Mechanism overview

1. Halogenoalkane → carbocation

2. Nucleophile attacks carbocationNucleophile attacks carbon at the same time as halide leaves

Rate equation

Rate = k[halogenoalkane]

(reaction rate depends only on the conc of halogenoalkane)Rate = k[halogenoalkane][nucleophile] - (reaction rate depends on the concentrations of both the haloalkane and the nucleophile.)

Rate-determining step

Formation of carbocation (step 1)

Simultaneous attack (only step)

Type of halogenoalkane

Tertiary (or sometimes secondary)

Primary (or sometimes secondary)

Why?

Carbocation is more stable due to alkyl groups

Less steric hindrance for backside attack

Intermediate

Yes — carbocation

No — just a transition state

Transition state

Not applicable (intermediate forms fully)

Yes — partial bonds between carbon, nucleophile, and halide

Nucleophile strength

Can be weak (e.g. H₂O, alcohol)

Must be strong (e.g. OH⁻, CN⁻, NH₃)

Solvent

Polar protic solvents (e.g. water, alcohols)

Polar aprotic solvents (e.g. acetone, DMF)

Stereochemistry

Racemic mixture (equal attack from both sides)

Inversion of configuration (backside attack)

Carbocation stability

Crucial — tertiary most stable

Not needed — no carbocation forms

Reaction speed

Faster for tertiary compounds

Faster for primary compounds

Key Concepts to Remember💥 SN1:

Happens because the carbocation is stable.

Only depends on halogenoalkane concentration.

Produces a racemic mixture due to planar carbocation → equal chance of nucleophile attacking from either side.

Common for tertiary halogenoalkanes.

⚡ SN2:

Happens because the nucleophile can easily approach the carbon (less steric hindrance).

Involves simultaneous attack and leaving group departure.

Produces inversion of configuration.

Common for primary halogenoalkanes.

steric hindrance

What is steric hindrance?

It means how crowded or blocked the area around a particular atom or bond is by other atoms or groups.

Imagine trying to park a car in a tight space with lots of obstacles — that’s like a reaction site with high steric hindrance.

If there are fewer obstacles, it’s easier to “park” — meaning, easier for other molecules to approach and react.

🔹 What is backside attack?

In an SN2 reaction, the nucleophile attacks the carbon atom opposite the side where the leaving group is attached.

This is called a backside attack because the nucleophile comes from the opposite side of the halogen.

🔹 So, “less steric hindrance for backside attack” means:

If the carbon attached to the halogen is surrounded by small groups (like hydrogens in primary halogenoalkanes), there’s more space.

The nucleophile can easily get in from the opposite side and attack.

But if the carbon is surrounded by big bulky groups (like in tertiary halogenoalkanes), the nucleophile finds it hard to get in and attack from behind because it's “blocked” or crowded.

🧠 Simple analogy:

Primary halogenoalkane → The nucleophile has a clear path for attack (less steric hindrance).

Tertiary halogenoalkane → The nucleophile faces a crowded road and can’t easily attack (more steric hindrance).

reactivity of halogenoalkanes

When haloalkanes react, it is almost always the C-X bond that

breaks. There are two factors that determine how readily the

C-X bond reacts.

These are:

The C-X bond polarity

The C-X bond enthalpy

These factors compete during a reaction and deciding which isthe more important will depend on the substances reacting.

The halogenoalkanes have different rates of substitution reactions

Since substitution reactions involve breaking the carbon-halogen bond the bondenergies can be used to explain their different reactivities

Bond

Bond Energy / kJ mol–1

C–F

467 (strongest bond)

C–Cl

346

C–Br

290

C–I

228 (weakest bond)

The table above shows that the C-I bond requires the least energy to break, and is therefore the weakest carbon-halogen bond

During substitution reactions the C-I bond will therefore heterolytically break as follows:

R3C-I + OH–→R3C-OH + I–

halogenoalkane → alcohol

The C-F bond, on the other hand, requires the most energy to break and is, therefore, the strongest carbon-halogen bond

Fluoroalkanes will therefore be less likely to undergo substitution reactions while iodoalkanes will be the most reactive.

halogeonalkane + aqueous silver nitrate

Reacting halogenoalkanes with aqueous silver nitrate solution will result in the formation of a precipitate

The rate of formation of these precipitates can also be used to determine the reactivity of the halogenoalkanes

halogenoalkane precipitates

Chlorides

White (silver chloride) precipitate

Bromides

Cream (silver bromide)

Iodides

Yellow (silver iodide)

The formation of the pale yellow silver iodide is the fastest (fastest nucleophilic substitution reaction)

The formation of the silver fluoride is the slowest (slowest nucleophilic substitution reaction)

This confirms that fluoroalkanes are the least reactive and iodoalkanes are the most reactive halogenoalkanes

The trend in reactivity of halogenoalkanes

properties of haloalkanes

🧊 Physical Properties of Haloalkanes

Boiling Points

Higher than alkanes of similar molar mass due to polar C–X bonds (X = halogen).

Boiling point increases with:

Longer carbon chain

Heavier halogen (F < Cl < Br < I)

Example: CH₃Cl < CH₃Br < CH₃I

Solubility

Insoluble in water: They cannot form hydrogen bonds with water effectively.

Soluble in organic solvents (e.g. ethanol, ether, benzene).

Density

Heavier haloalkanes (especially iodoalkanes) are denser than water.

Generally, C–I > C–Br > C–Cl > C–F in density.

Polarity

The C–X bond is polar, especially for C–Cl and C–Br.

However, the overall molecule may be non-polar or only weakly polar depending on symmetry.

Volatility

Decreases as molar mass increases (heavier haloalkanes are less volatile).

⚗ Chemical Properties of Haloalkanes

Haloalkanes are quite reactive due to the polar and weak C–X bond. They undergo:

1. Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions

General form:

R–X + Nu⁻ → R–Nu + X⁻Nucleophiles include:

OH⁻ → alcohol

CN⁻ → nitrile

NH₃ → amine

H₂O → alcohol (slower)

Mechanisms:

SN1 (tertiary > secondary > primary)

SN2 (primary > secondary > tertiary)

2. Elimination Reactions (E1 or E2)

Reaction with strong base (e.g. OH⁻) → alkene

Competes with substitution

Follows Zaitsev’s Rule: more substituted alkene is major product.

3. Reaction with Metals

E.g., Grignard reagent formation:

R–X + Mg → R–MgX (in dry ether)

4. Reduction

Can be reduced to alkanes using reducing agents like:

Zn/HCl

LiAlH₄ (in organic synthesis)

5. Hydrolysis

With water or aqueous alkali:

R–X + H₂O → R–OH + HX

Summary Table

Property | Trend or Note |

|---|---|

Boiling Point | ↑ with molar mass and halogen size |

Solubility | Insoluble in water, soluble in organic solvents |

Density | ↑ with halogen size |

Reactivity | High due to polar C–X bond |

Main Reactions | Nucleophilic substitution, elimination, reduction, Grignard formation |

Mechanisms | SN1 (tertiary), SN2 (primary), E1/E2 for elimination |