Lecture 4 -2 Bipolar Disorders and suicide

1/60

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

61 Terms

Bipolar disorder Symptoms

Unlike those experiencing depression, people in a state of mania typically experience dramatic and inappropriate rises in mood

Emotional symptoms in bipolar disorder

Motivational symptoms in bipolar disorder

Behavioral symptoms in bipolar disorder

Cognitive symptoms in bipolar disorder

Physical symptoms in bipolar disorder

Diagnosing bipolar disorders

Two kinds of bipolar disorder (DSM-5)

Bipolar I disorder

Bipolar II disorder

Worldwide, 1 to 2.6 percent of all adults have bipolar disorder at any given time: 4 percent have it at some point in life

No gender differences, but higher rates in low-income populations

Manic episode

For 1 week or more, person displays a continually abnormal, inflated, unrestrained, or irritable mood as well as continually heightened energy or activity, for most of every day

Person also experiences at least three of the following symptoms for Manic episode

Grandiosity or overblown self-esteem

Reduced sleep need

Rapidly shifting ideas or the sense that one’s thoughts are moving very fast

Attention pulled in many directions

Heightened activity or agitated movements

Excessive pursuit of risky and potentially problematic activities

Bipolar I disorder

Occurrence of a manic episode

Hypomanic or major depressive episodes may precede or follow the manic episode

Bipolar II disorder

Presence or history of major depressive episode(s)

Presence or history of hypomanic episode(s)

No history of a manic episode

Cyclothymic disorder (DSM-5)

Numerous periods of hypomanic symptoms and mild depression symptoms

Symptoms continue for two or more years, with normal moods for days or weeks in between

No gender differences

May evolve into bipolar I or bipolar II

What Causes Bipolar Disorders?

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the search for the cause of bipolar disorders made little progress.

More recently, biological research has produced some promising clues

These insights have come from research into neurotransmitter activity, ion activity, brain structure, and genetic factors

Biological research and perspectives - Neurotransmitter activity

Mania may be related to high norepinephrine activity along with a low level of serotonin activity (“permissive theory”)

Biological research and perspectives - Ion activity

Improper transport of ions back and forth between the outside and the inside of a neuron’s membrane

Biological research and perspectives -Brain structure

Brain imaging and postmortem studies have identified a number of abnormal brain structures in people with bipolar disorder —in particular, the basal ganglia and cerebellum

Not clear what role such structural abnormalities play

Genetic factors

Many theorists believe that people inherit a biological predisposition to develop bipolar disorders

Family pedigree studies

Molecular biology techniques

Treatments for Bipolar Disorders

Before 1970, treatments for people with bipolar disorders were largely ineffective

In 1970, FDA approved the use of lithium

Mood-stabilizing (antibipolar) drugs were later developed

Lithium

Very effective in treating bipolar disorders and mania

Determining the correct dosage for a given patient is a delicate process

Too low = no effect

Too high = lithium intoxication (poisoning)

Other mood stabilizers

Some patients respond better to other drugs or to combinations of drugs

Effectiveness of lithium and other mood stabilizers

More than 60 percent of patients with mania improve on these medications

Most individuals experience fewer new episodes while on the drugs

These drugs may help prevent symptoms from developing

Mood stabilizers also help those with bipolar disorder overcome their depressive episodes, albeit to a lesser degree

Adjunctive psychotherapy

Psychotherapy or mood stabilizing alone is rarely helpful for persons with bipolar disorder

Individual, group, or family therapy is often used as an adjunct to lithium (or other medication-based) therapy

Adjunctive therapy improves a variety of client behaviors, especially in those persons with a cyclothymic disorder

Unipolar depression factors

Biological abnormalities

Positive reinforcement reduction • Negative thinking

Perception of helplessness

Life stress

Sociocultural influences

Bipolar depression factors

• Biological abnormalities

Inherited

Stress triggered

What are

the one-year prevalence

female-to-male ratio

typical age at onset

prevalence among first-degree relatives

percentage receiving treatment for Major Depressive Disorder?

Prevalence: 8.0%

Female-to-Male Ratio: 2:1

Typical Age at Onset: 18−29 years

Prevalence Among First-Degree Relatives: Elevated

Percentage Receiving Treatment: 50%

What are

the one-year prevalence

female-to-male ratio

typical age at onset

prevalence among first-degree relatives

percentage receiving treatment for Persistent Depressive Disorder (with dysthymic syndrome)?

Prevalence: 1.5−5.0%

Female-to-Male Ratio: Between 3:2 and 2:1

Typical Age at Onset: 10−25 years

Prevalence Among First-Degree Relatives: Elevated,

Percentage Receiving Treatment: 62%

What are

the one-year prevalence

female-to-male ratio

typical age at onset

prevalence among first-degree relatives

percentage receiving treatment for Bipolar I Disorder?

Prevalence: 1.6%

Female-to-Male Ratio: 1:1

Typical Age at Onset: 15−44 years

Prevalence Among First-Degree Relatives: Elevated

Percentage Receiving Treatment: 49%

What are

the one-year prevalence

female-to-male ratio

typical age at onset

prevalence among first-degree relatives

percentage receiving treatment for Bipolar II Disorder?

Prevalence: 1.0%

Female-to-Male Ratio: 1:1

Typical Age at Onset: 15−44 years

Prevalence Among First-Degree Relatives: Elevated

Percentage Receiving Treatment: 49%

What are

the one-year prevalence

female-to-male ratio

typical age at onset

prevalence among first-degree relatives

percentage receiving treatment for Cyclothymic Disorder?

Prevalence: 0.4%

Female-to-Male Ratio: 1:1

Typical Age at Onset: 15−25 years

Prevalence Among First-Degree Relatives: Elevated

Percentage Receiving Treatment: Unknown

Suicide

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death in the world

Approximately 1 million people die by suicide each year worldwide, including more than 42,000 in the United States

Classification

Not officially classified as a mental disorder in DSM-5

Suicidal behavior disorder has been proposed for the next revision

Definition of Suicide

Self-inflicted death in which one makes intentional, direct, and conscious effort to end one’s life

Intentional death

Death seeker

Death initiator

Death ignorer

Death darer

Non-suicidal self-injury

The deliberate, self-directed damage to body tissue without suicidal intent and for purposes not socially or culturally sanctioned.

Increases capability for suicide, which increases the risk later in life

Suicide rates vary

Country to country

Gender and marital status

Race and ethnicity

Social environment

Religious devoutness (not exclusively affiliation)

Underreporting may exist

Common triggers

Stressful events

Mood and thought changes

Alcohol and other drug use

Mental disorders

Modeling

Stressful events and situations for suicide = Immediate stressors

Loss of loved one through death, divorce, or rejection

Loss of job or significant financial loss

Natural disasters

Stressful events and situations for suicide = Long-term stressors

Social isolation

Serious illness

Abusive or repressive environment

Occupational stress

Mood and thought changes

Many suicide attempts are preceded by changes in mood and shifts in thinking patterns

Hopelessness

Sadness, anxiety, tension, frustration, shame

Psychache

Dichotomous thinking

Alcohol and other drug use

70 percent of suicide at tempters drink alcohol just before the act

One-fourth of these people are legally intoxicated

Use of other kinds of drugs may have similar ties to suicide, particularly in teens and young adults

Mental disorders

The majority of suicide attempters have a psychological disorder

Unipolar or bipolar depression (70 percent)

Chronic alcoholism (20 percent)

Schizophrenia (10 percent)

• Risk increases with multiple disorders

Other psychological disorders to triggers a suicide

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Panic disorder

Substance use disorder

Often in conjunction with schizophrenia or borderline personality disorder

Modeling: Contagion of suicide

A suicidal act appears to serve as a model for other such acts, especially among teens

Common models

Family members and friend

Celebrities

Highly publicized cases

Coworkers and colleagues

Interpersonal-psychological theory (Joiner et al.)

Perceptions related to desire for suicide

Perceived burdensomeness

Thwarted belongingness

Psychological ability to carry out suicide (capability for suicide)

Important to examine variables collectively

Biological view of Suicide

Genetics

Early twin studies port to genetic links to suicide

Brain development

Low serotonin activity and abnormalities in depression-related brain circuits contribute to suicide

Both aid in the production of aggressive feelings and impulsive behavior

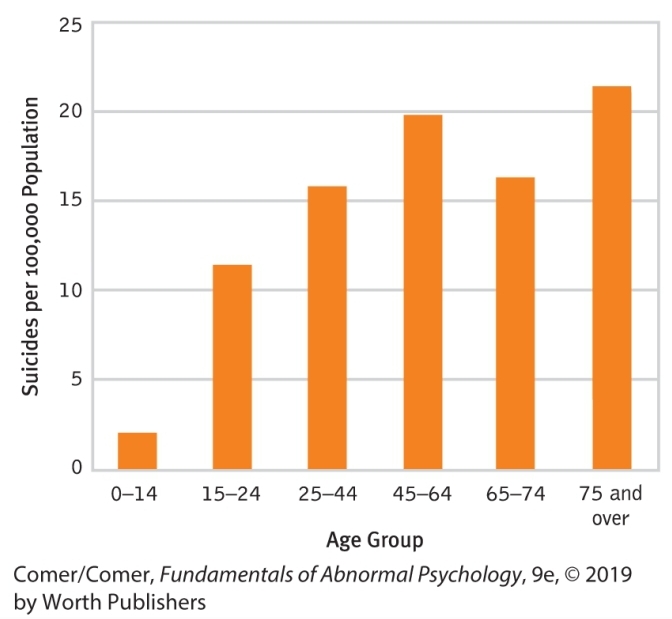

Is Suicide Linked to Age?

Children - Suicide

Suicide is infrequent among children

Suicide by very young is often preceded by behavioral struggles

Many child suicides appear to be based on a clear understanding of death and a clear wish to die

Adolescents - Suicide

Suicidal actions become much more common after the age of 13

About 8 of every 100,000 U.S. teenagers commit suicide yearly

12 percent have persistent suicidal thoughts

4 to 8 percent make suicide attempts

Teenage suicide links

Developmental stress of adolescence

Long- and short-term stressors, especially among LGBTQ teens

Clinical depression, low self-esteem, hopelessness

Anger, impulsiveness, alcohol or drug problems

Internet and in-person modeling

Factors linked to suicide attempts for Adolescents

Competition for jobs, college position, academic and athletic honors

Weakening family ties

Availability of alcohol/drugs

Mass media

Far more teens attempt suicide than succeed

Ratio may be as high as 200:1

The Elderly - suicide

U.S. elderly are most likely to commit suicide and most successful

Contributory factors of suicide in Elderly

Illness

Loss of close friends and relatives

Loss of control over one's life

Loss of social status

Treatments after suicide attempts

Medical care

Appropriate follow-up with psychotherapy or drug therapy

Therapies for Suicide.

Psychodynamic

Drug therapy

Group and family therapies

Cognitive - behavioural therapy

Mindfulness - based

Dialectical Behaviour

Therapy goals after suicide attempts

Keep the patient alive

Reduce psychological pain

Achievement of nonsuicidal state of mind and a sense of hope

Development of better ways of stress management

Suicide prevention

Prevention programs and crisis hotlines

Staffed by professionals or paraprofessionals

Offered through various modalities

Suicide prevention goals for initial contact

Establishing a positive relationship

Understanding and clarifying the problem

Assessing suicide potential

Assessing and mobilizing the caller's resources

Formulating a plan

Longer-term prevention of Surcide

Referral

Therapy

Reduction of access to common suicide means

Do suicide prevention programs work?

Assessment of program effectiveness is difficult

Variety of program types, variables, and confounds

Mixed results

• Accurate suicide risk assessment is elusive

Newer assessment approaches for suicide prevention programs

Nonverbal behaviors

Psychophysiological measures

Brain scans

Self-Injury Implicit Association Test

Following the break-up with his girlfriend, Eduard (27) has been feeling down for the past week, complaining that he has difficulties concentrating, is unable to sleep but feels nonetheless tired, feels agitated, and has been gaining some weight. He does not, however, have a history of mania. According to the DSM-5, Eduard would classify for the following diagnosis:

No disorder