MyEdSpace Module 1: Biological Monomers

1/124

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

125 Terms

Monomer

A small unit that can form larger molecules.

Polymer

A large molecule made of repeating monomer units.

Condensation reaction

A reaction where monomers join by making bonds and releasing water.

Hydrolysis reaction

A reaction where polymers break down with the addition of water.

Carbohydrates

Purpose: Provide energy, structural support, and aid cell recognition

Monomer: Monosaccharides like glucose, galactose, and fructose

Polymer: Polysaccharides or sugars

Condensation bond: glycosidic bonds

Hydrolysis enzymes: amylase, lactase, maltase

Contain the elements: carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen.

Monosaccharides

Definition: The monomer of carbohydrates, containing carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen in a ratio of (CH₂O)n.

Examples: Glucose, Galactose, Fructose

Function: Quick energy source.

Properties: Soluble

Hexoses

α-glucose (used in energy storage and respiration)

β-glucose (used in structural molecules like cellulose)

Fructose (found in fruits, an alternative energy source)

Galactose (part of lactose, important in milk digestion)

Pentoses

Ribose (used to make nucleic acids: RNA)Deoxyribose (used to make nucleic acids: DNA)

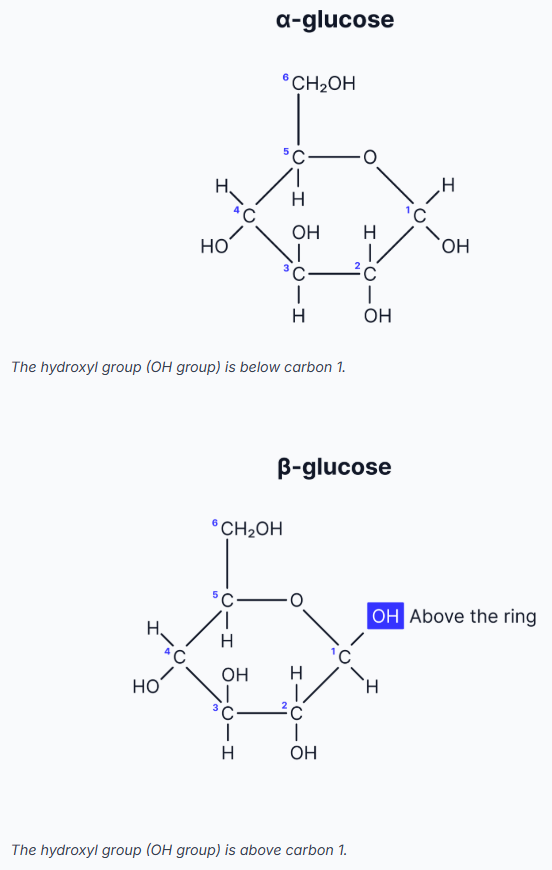

Structure of Glucose

Both α- and β-glucose have six carbon atoms (hexose sugars).

α- and β-glucose are isomers of each other.

The carbons are numbered starting clockwise from the O in the ring.

The difference between α- and β-glucose is the position of the hydroxyl (-OH) group on carbon 1.

Isomers

Molecules with the same formula but different structures (e.g., α- and β-glucose). These differences influence their biological roles.

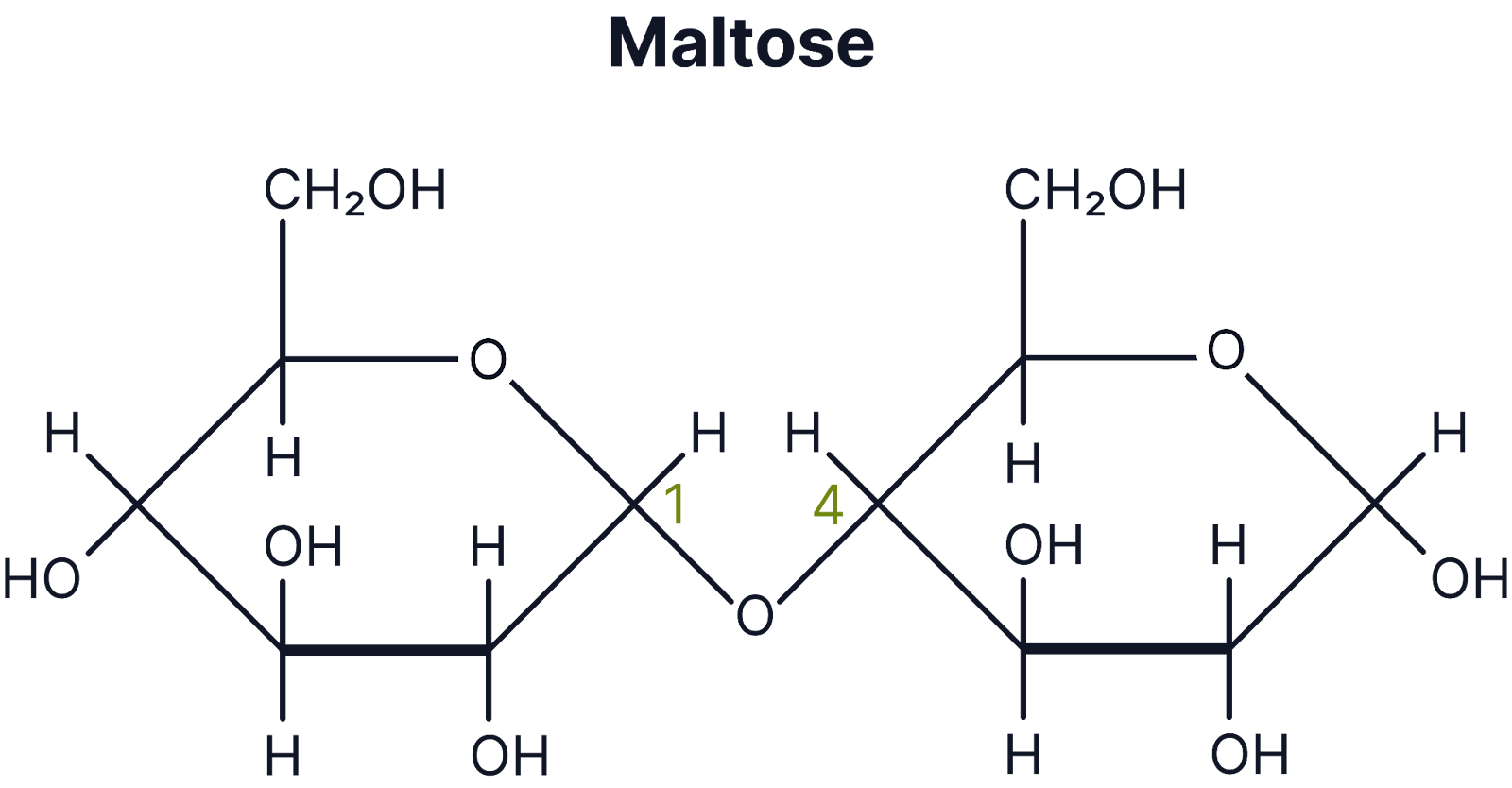

Disaccharides

Definition: Carbohydrates formed when two monosaccharides join via a glycosidic bond.

Examples: Maltose, Sucrose, Lactose

Function: Energy transport and storage.

Properties: Soluble

Maltose

α-glucose + α-glucose (important in digestion and germination)

Sucrose

glucose + fructose (common table sugar, transported in plants)

Lactose

glucose + galactose (found in milk, important for infant nutrition)

Polysaccharides

Definition: A complex carbohydrate formed from many, repeated monosaccharides joined by glycosidic bonds through condensation reactions.

Examples: Starch, Glycogen, Cellulose

Functions: Energy storage (starch in plants, glycogen in animals); structural support (cellulose in plants).

Properties: Insoluble

Glycosidic Bond

The covalent bond that links monosaccharides, crucial for carbohydrate formation.

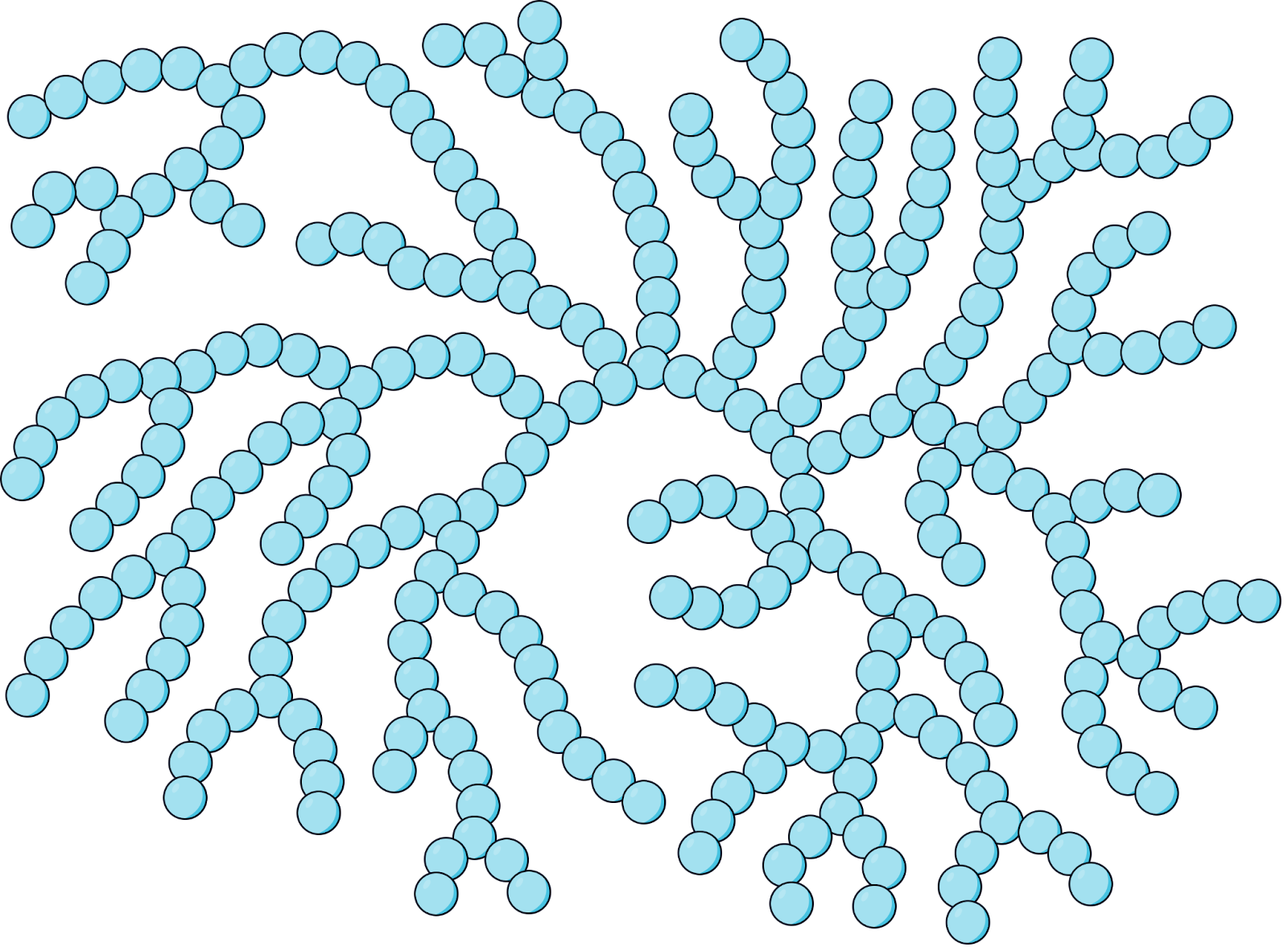

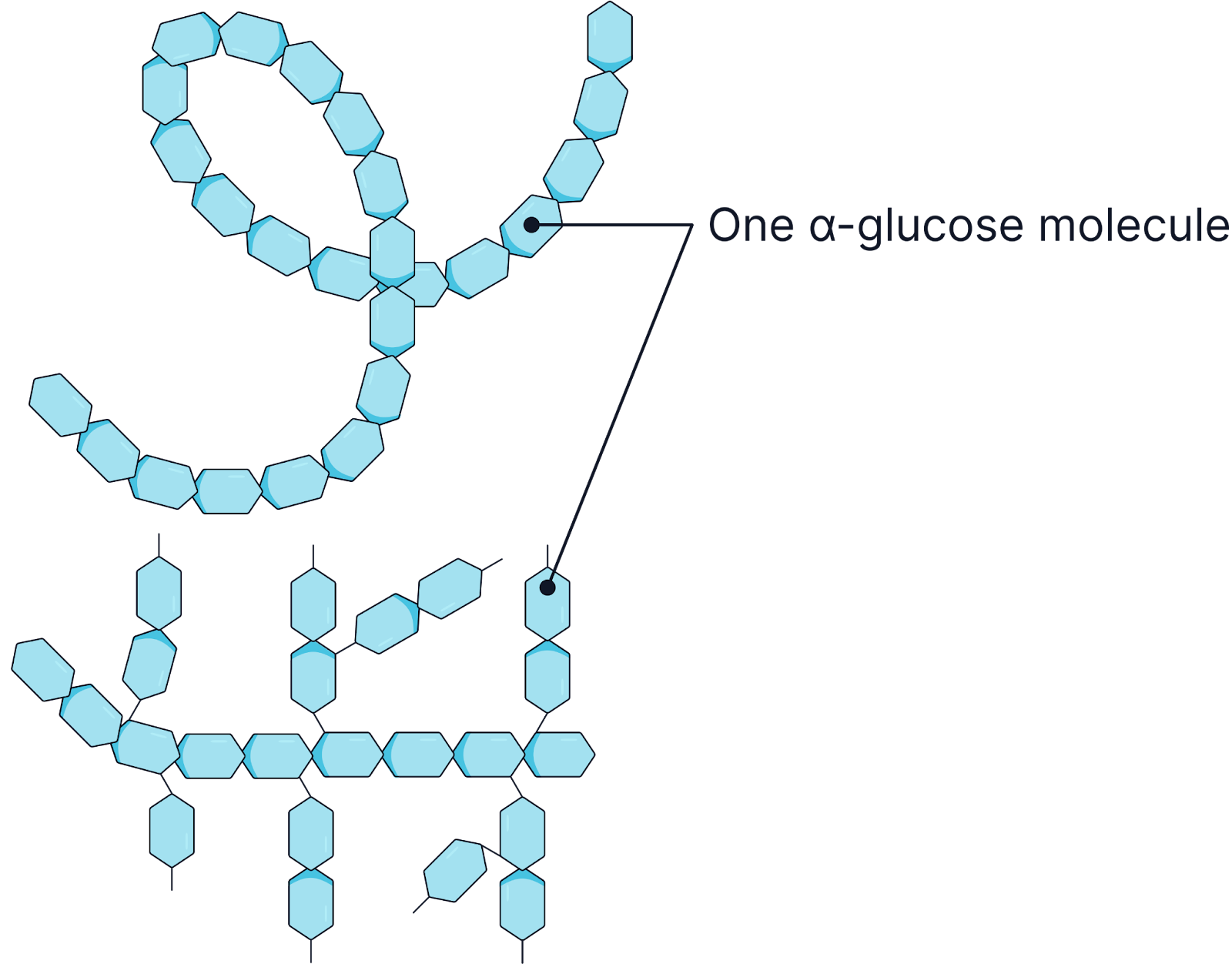

Glycogen (Storage in Animals)

Made of many α-glucose monomers.

Highly branched structure with 1,4 and 1,6 glycosidic bonds, allowing enzymes to rapidly hydrolyse glycogen into glucose (to be used in respiration)..

Found in animal cells, particularly in liver and muscle cells.

Insoluble, preventing osmotic effects in animal cells as it does not affect the water potential.

Large molecule meaning it cannot diffuse out of cells

Starch (Storage in Plants)

Made of many α-glucose molecules.

Exists in two forms:

Amylose: A helical, unbranched structure with 1,4 glycosidic bonds, making it compact. This means lots can be stored in a small space.

Amylopectin: Branched, with 1,4 and 1,6 glycosidic bonds, allowing rapid hydrolysis by enzymes to release glucose for respiration.

Insoluble, preventing osmotic effects in plant cells as it does not affect the water potential.

Large molecule meaning it cannot diffuse out of cells.

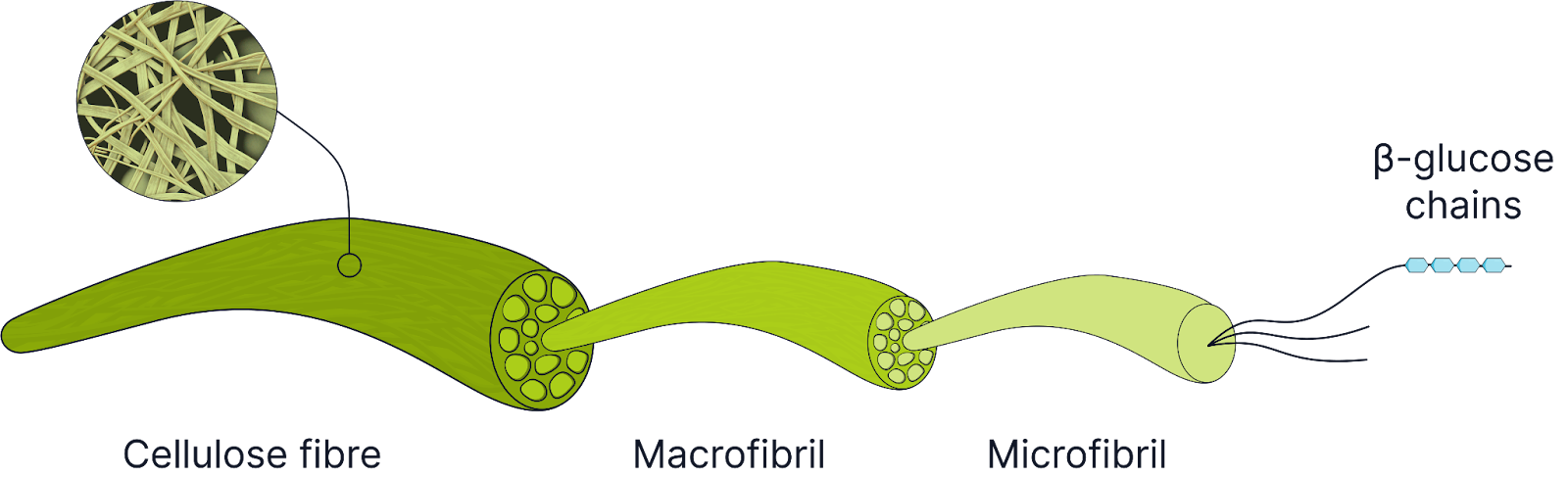

Cellulose (Structural in Plants)

Made of many β-glucose molecules.

Long, straight, unbranched chains with 1,4 glycosidic bonds.

Straight chains are held together by many hydrogen bonds to form microfibrils.

Microfibrils are joined together to make macrofibrils.

Many hydrogen bonds help give structural strength to cellulose and plant cell walls, preventing plant cells from bursting under osmotic pressure

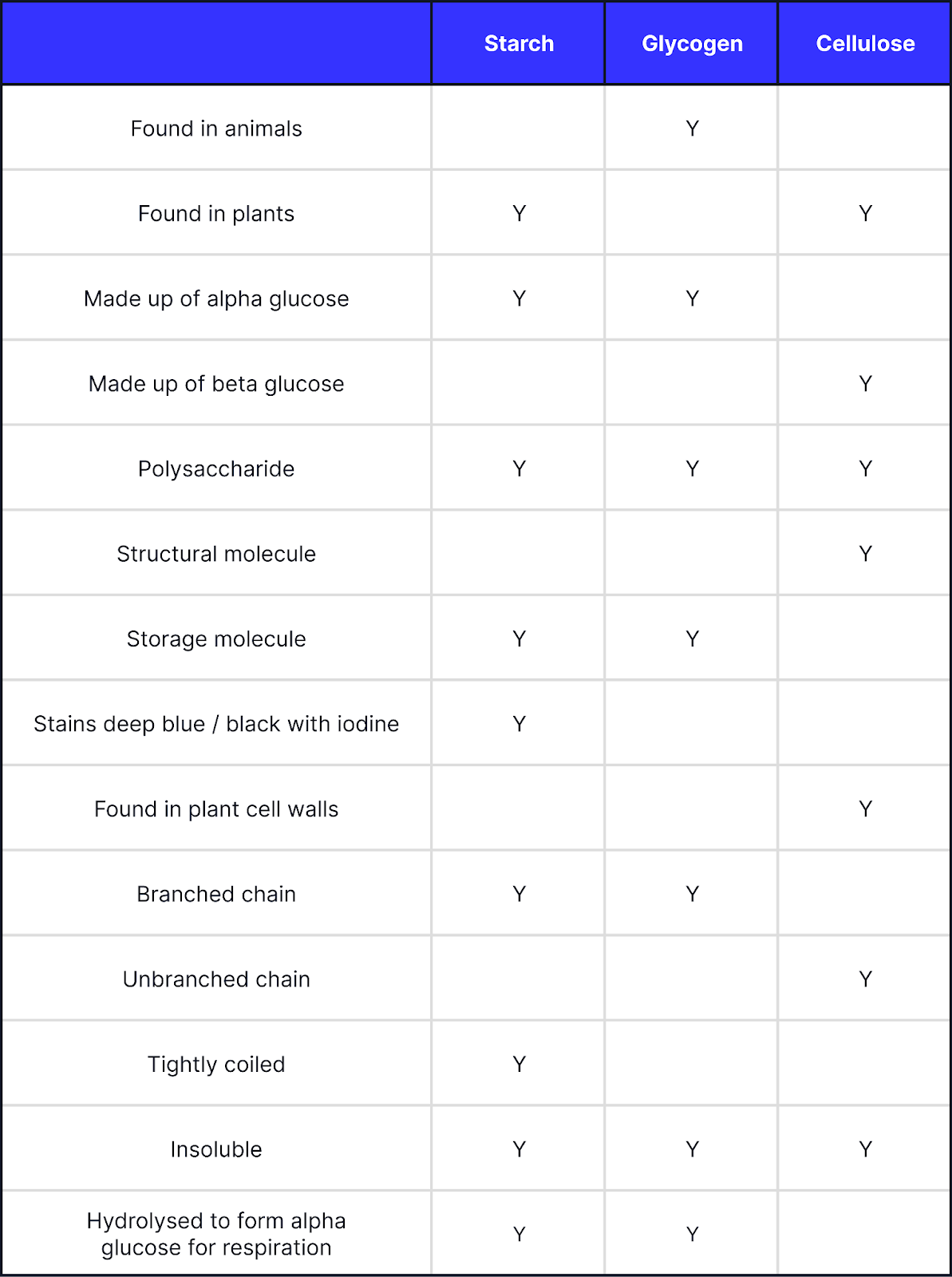

Starch vs Glycogen vs Cellulose

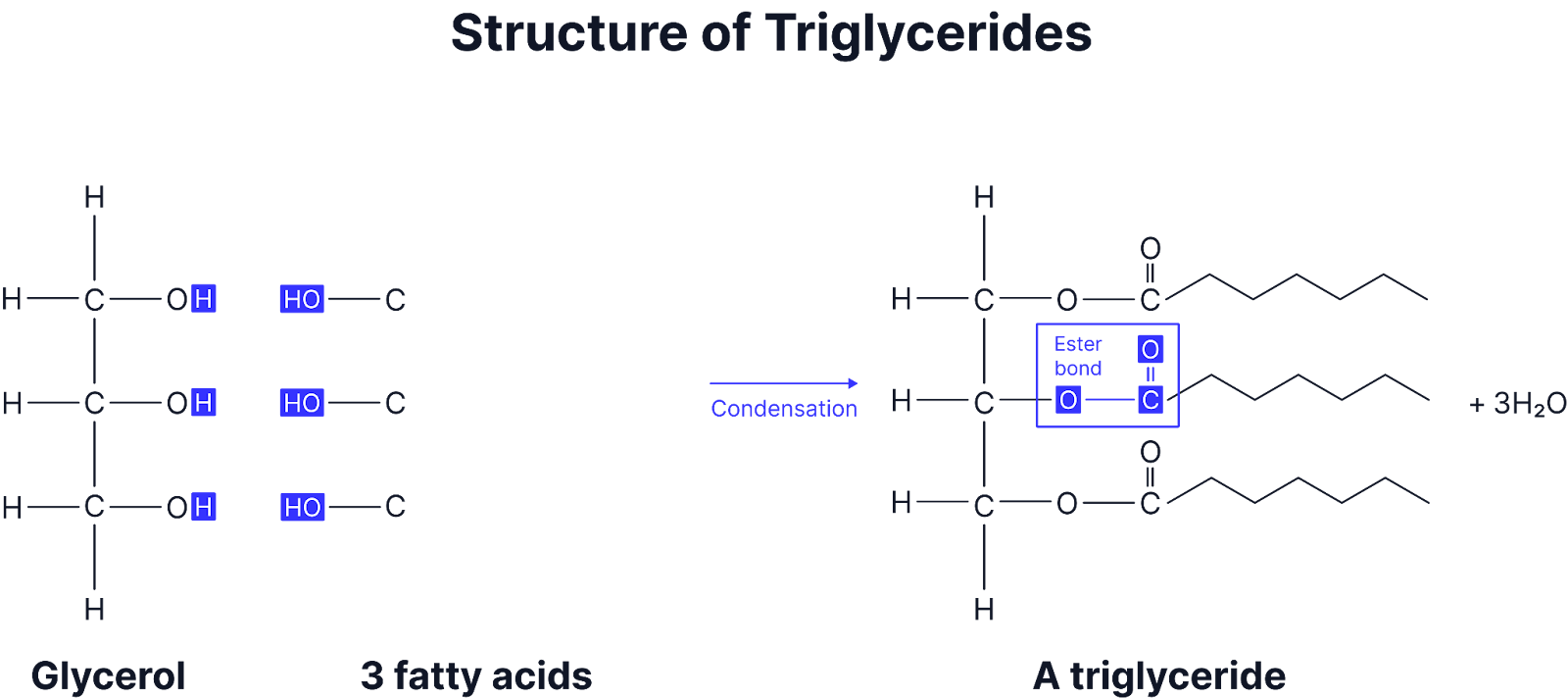

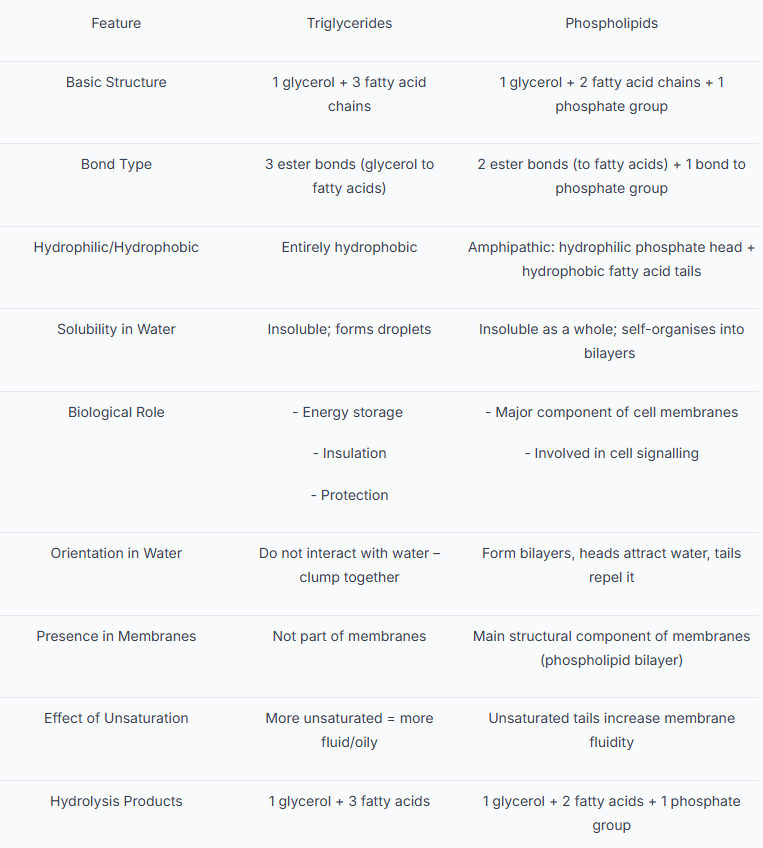

Lipids

Purpose: energy stores, insulation, protection, Waterproofing, membrane structure

Biological molecules: triglycerides and phospholipids

Condensation bond: ester bonds

Hydrolysis enzymes: lipases, phospholipases

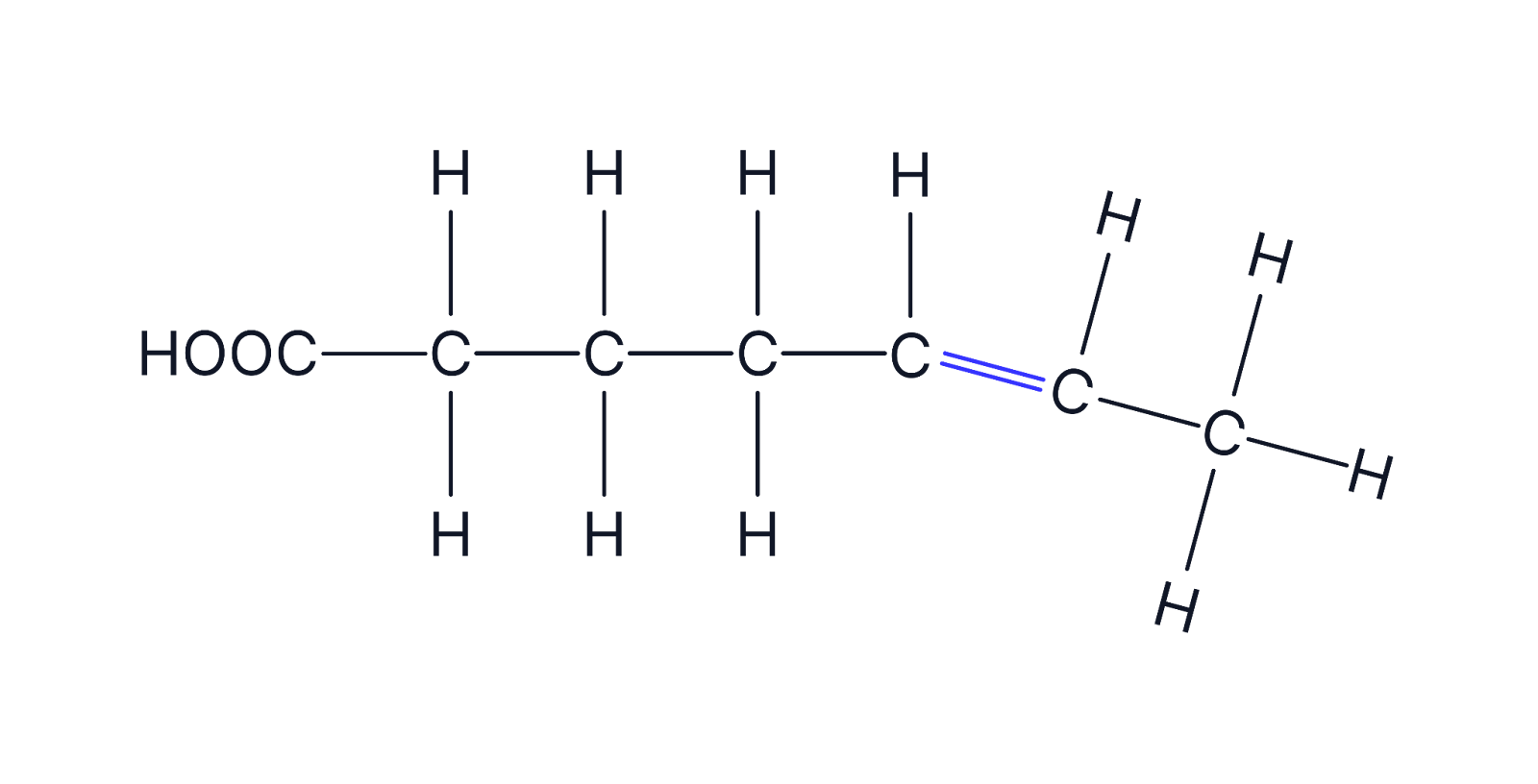

Contain the elements: carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. Always a fatty acid present, which has a carboxyl group (COOH) and carbon chain.

Saturated fatty acids

Only single bonds (No C=C double bonds) between carbon atoms in the hydrocarbon chain; straight chains

Found in animal fats (e.g., butter, lard).

Solid at room temperature due to closely packed molecules

Unsaturated fatty acids

Contain one (monounsaturated) or multiple (polyunsaturated) double C=C bonds the hydrocarbon chain; bent chains

Found in plant oils (e.g., olive oil, sunflower oil).

Liquid at room temperature because double bonds create kinks, preventing tight packing between the phospholipids.

Hydrophobic

Repels water, like the fatty acid tails of lipids.

Ester Bond

The bond formed between glycerol and fatty acids in a condensation

Hydrophilic

Attracts water, like the phosphate head of phospholipids

Triglycerides

Formed: A lipid with 3 fatty acid chains and glycerol

Condensation bond: Ester bond

Hydrolysis enzymes : lipases

Function and uses:

Energy Storage:

Triglycerides have a high ratio of carbon-hydrogen bonds, making them excellent energy stores.

They provide more energy per gram than carbohydrates.

Waterproofing:

They are insoluble in water (hydrophobic) so do not affect water potential and do not affect osmosis in cells.

Used for waterproofing in waxy cuticles of plants and insect exoskeletons.

Insulation:

Act as thermal insulators in mammals (e.g., blubber in whales)

Provide electrical insulation around nerve cells.

Protection:

Stored around vital organs to provide mechanical protection (e.g., kidneys).

Buoyancy: Triglycerides are less dense than water, helping aquatic animals such as seals and whales to stay afloat.

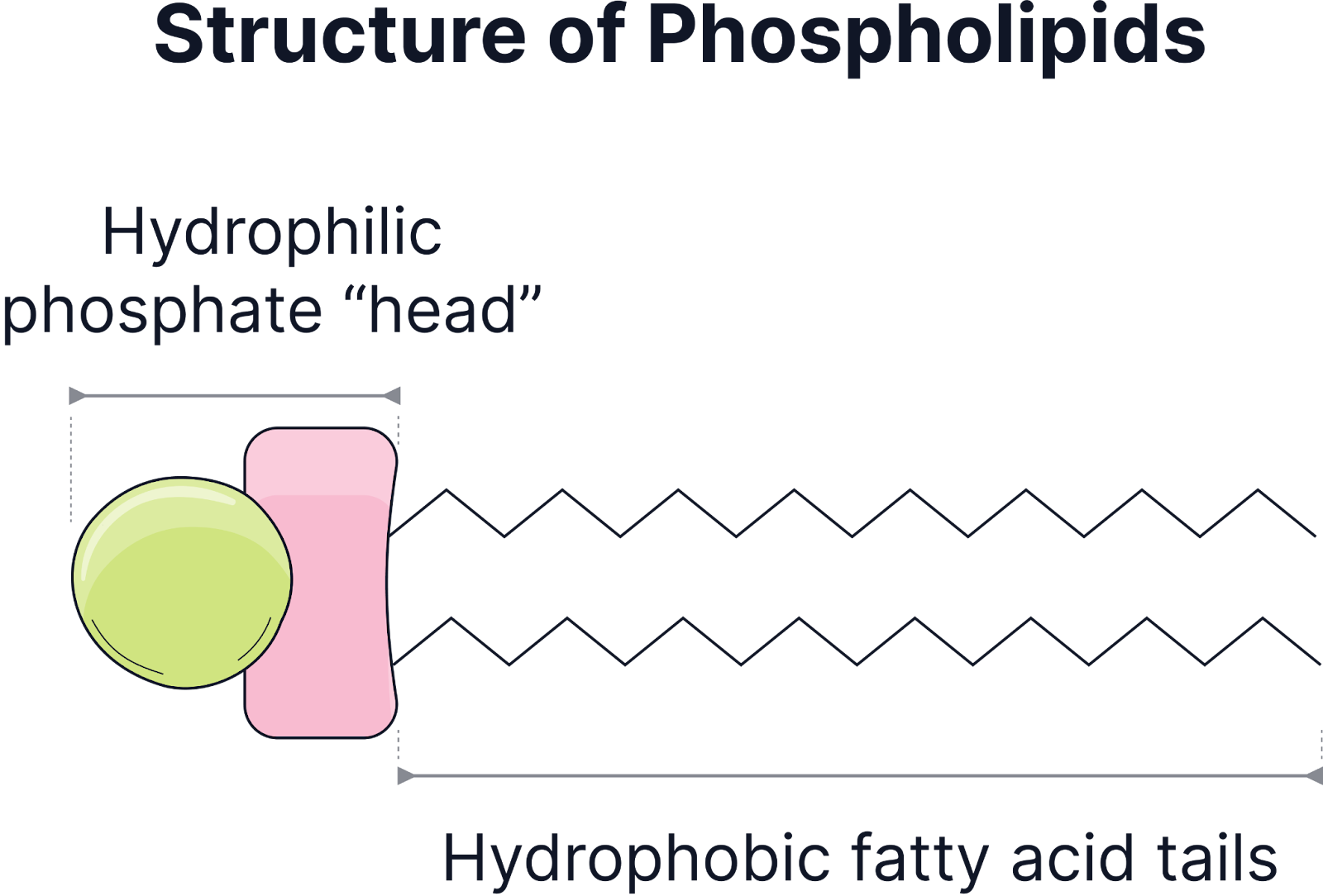

Phospholipids

Structure: A lipid with one glycerol molecule and a phosphate group (hydrophilic head) attracted to water and two fatty acid molecules (hydrophobic tails) which repel water. This dual nature allows phospholipids to arrange into a bilayer in cell membranes.

Condensation reaction bond: ester bond.

Hydrolysis enzymes: phospholipases

Properties:

Amphipathic nature

Hydrophilic phosphate head interacts with water.

Hydrophobic fatty acid tails avoid water and face inward in a bilayer.

Forms a bilayer in aqueous solutions

This is crucial for the structure of the plasma membrane.

Partially permeability

Small, non-polar molecules (e.g., oxygen, carbon dioxide) can diffuse through easily.

Large, polar molecules require transport proteins to cross the membrane.

Water is polar but is small enough that it can diffuse through the phospholipid bilayer.

Function:

Major component of cell membranes (phospholipid bilayer).

Provides fluidity to the membrane, allowing flexibility and movement. This is because the phospholipids can move laterally.

Acts as a barrier to large, water-soluble molecules, helping regulate entry and exit from the cell.

Bilayer

A double layer of phospholipids that forms the structure of the cell membrane.

Amphipathic

A molecule that has both hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions.

Selective Permeability

The ability of the cell membrane to allow certain molecules to pass while blocking others.

Triglycerides vs Phospholipids

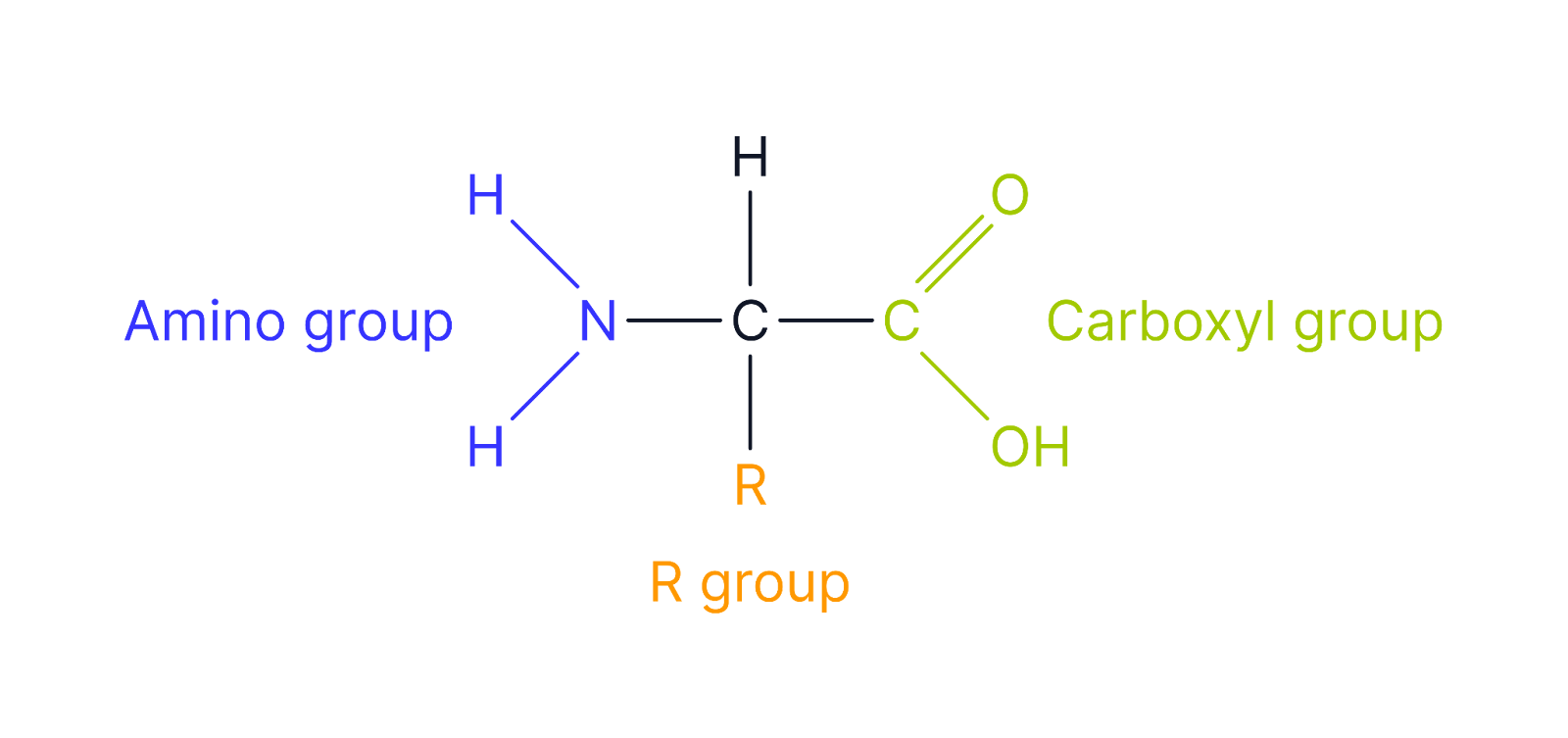

Proteins

The structure of a protein is critical to its function as proteins rely on their specific 3D shape as determined by their primary structure.

Monomer: amino acids

Polymer: polypeptides

Condensation bond: peptide bonds

Hydrolysis enzyme:

Contain the elements: carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and 2 contain sulfur

Properties:

Diverse Functions – Structural, enzymatic, transport, and signalling roles.

Solubility – Some proteins (e.g., enzymes) are soluble, while others (e.g., structural proteins like collagen) are insoluble.

Denaturation – High temperature or extreme pH can alter protein structure, affecting function.

Functions:

Enzymes – Biological catalysts (e.g., amylase, DNA polymerase).

Structural Proteins – Provide support (e.g., collagen in connective tissues, keratin in hair and nails).

Transport Proteins – Move substances across membranes (e.g., channel and carrier proteins). Haemoglobin transports oxygen in the blood,

Hormones – Chemical messengers (e.g., insulin, glucagon)

Antibodies – Part of the immune response, recognizing and neutralizing pathogens.

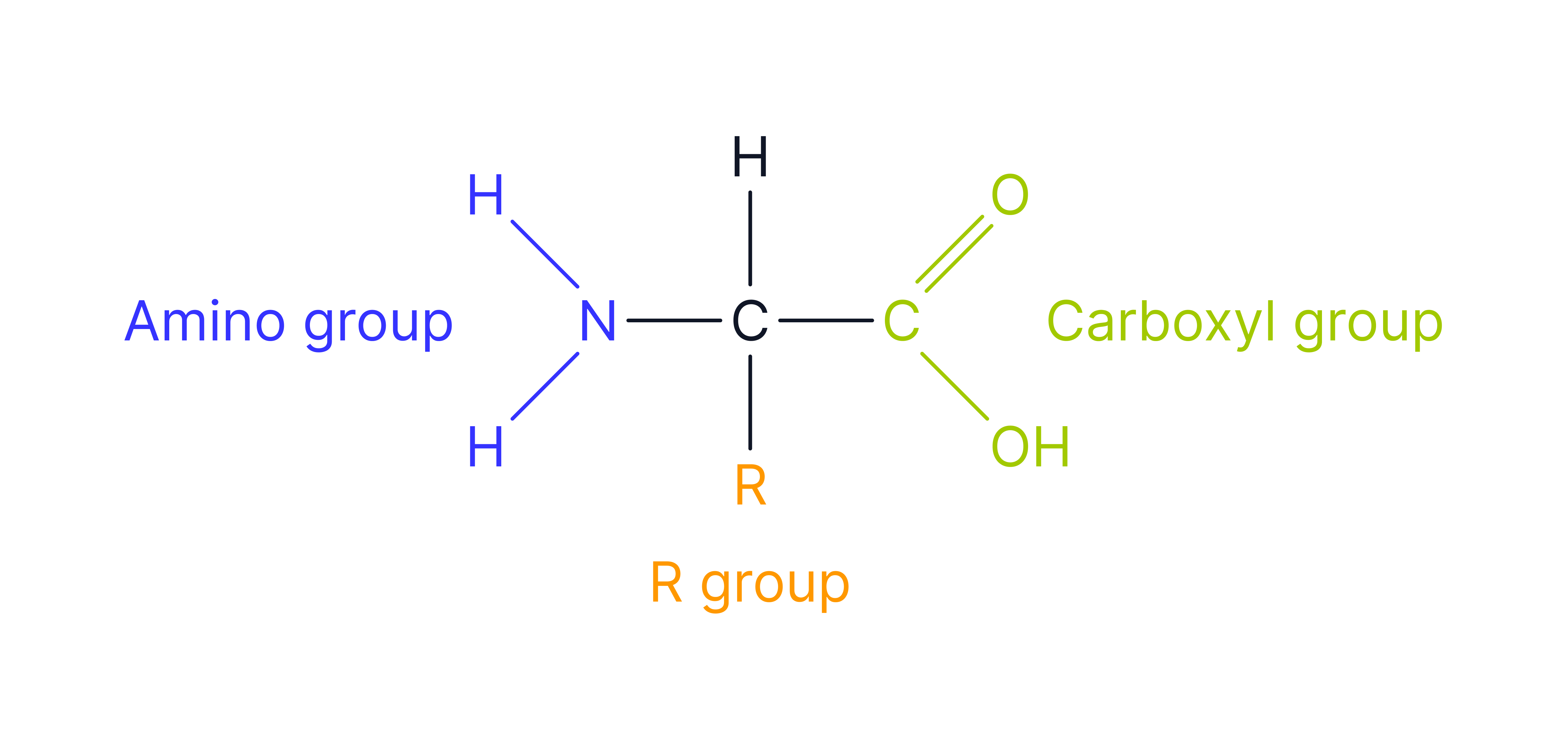

Amino Acid

The monomer unit of proteins. The central carbon (C) atom bonded to an amine group (-NH₂), carboxyl group (-COOH), hydrogen atom (H) and a variable R group (different in each amino acid).

Peptide Bond

A covalent bond that links amino acids together in a protein.

Enzyme

A biological catalyst that speeds up chemical reactions.

Denaturation

A permanent change in the bonds holding the enzyme/ protein’s tertiary structure structure due to high temperature or extreme pH.

Globular Proteins

Soluble proteins with metabolic roles (e.g., enzymes).

Fibrous Proteins

Structural proteins (e.g., collagen, keratin).

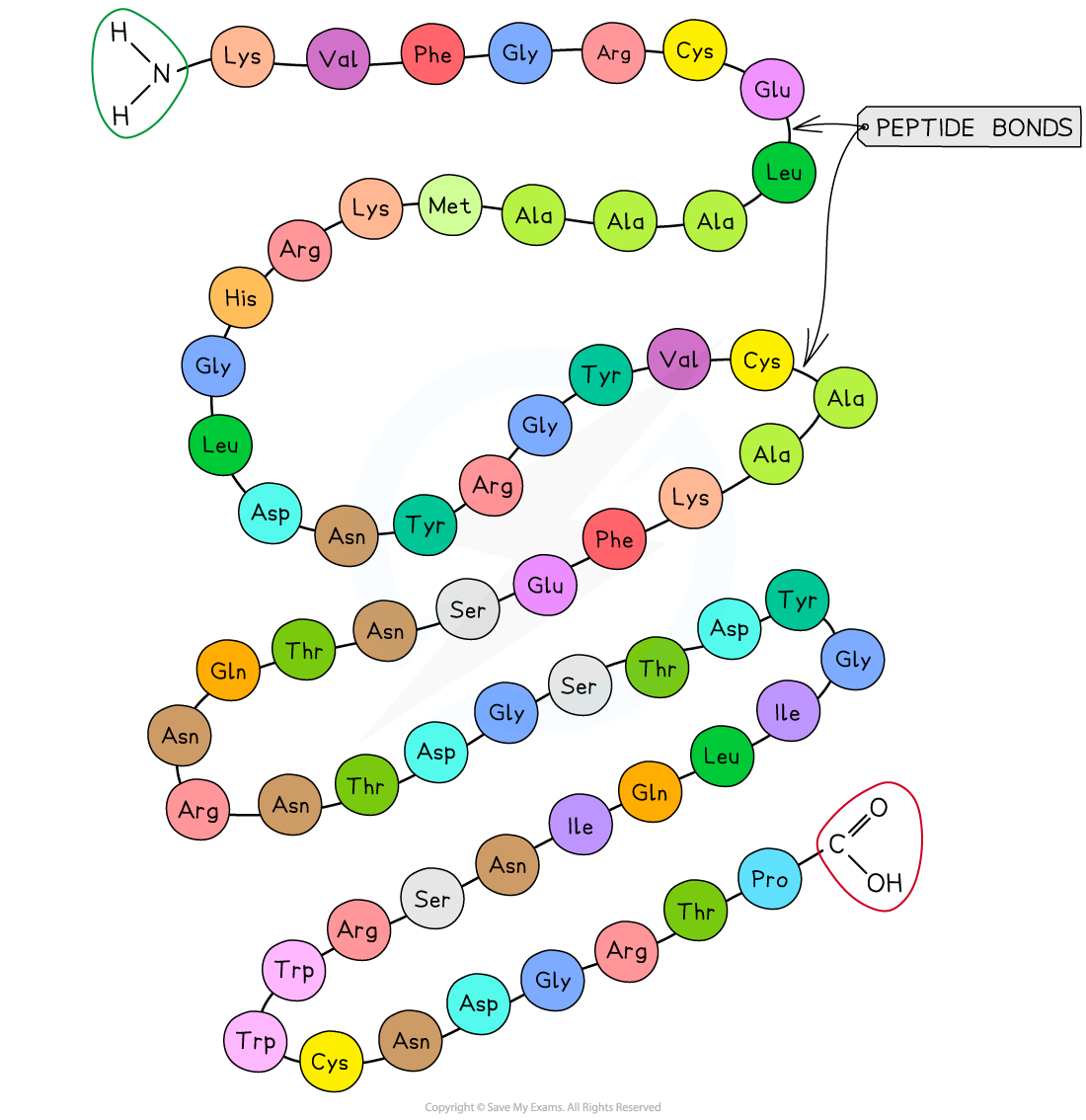

Primary Structure

The specific sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain.

Joined by peptide bonds formed in condensation reactions.

Peptide bonds form between the carboxyl group of one amino acid and the amine group of the next

Determines the protein’s ultimate shape and function as the primary structure will determine the position of the bonds that hold the tertiary structure together.

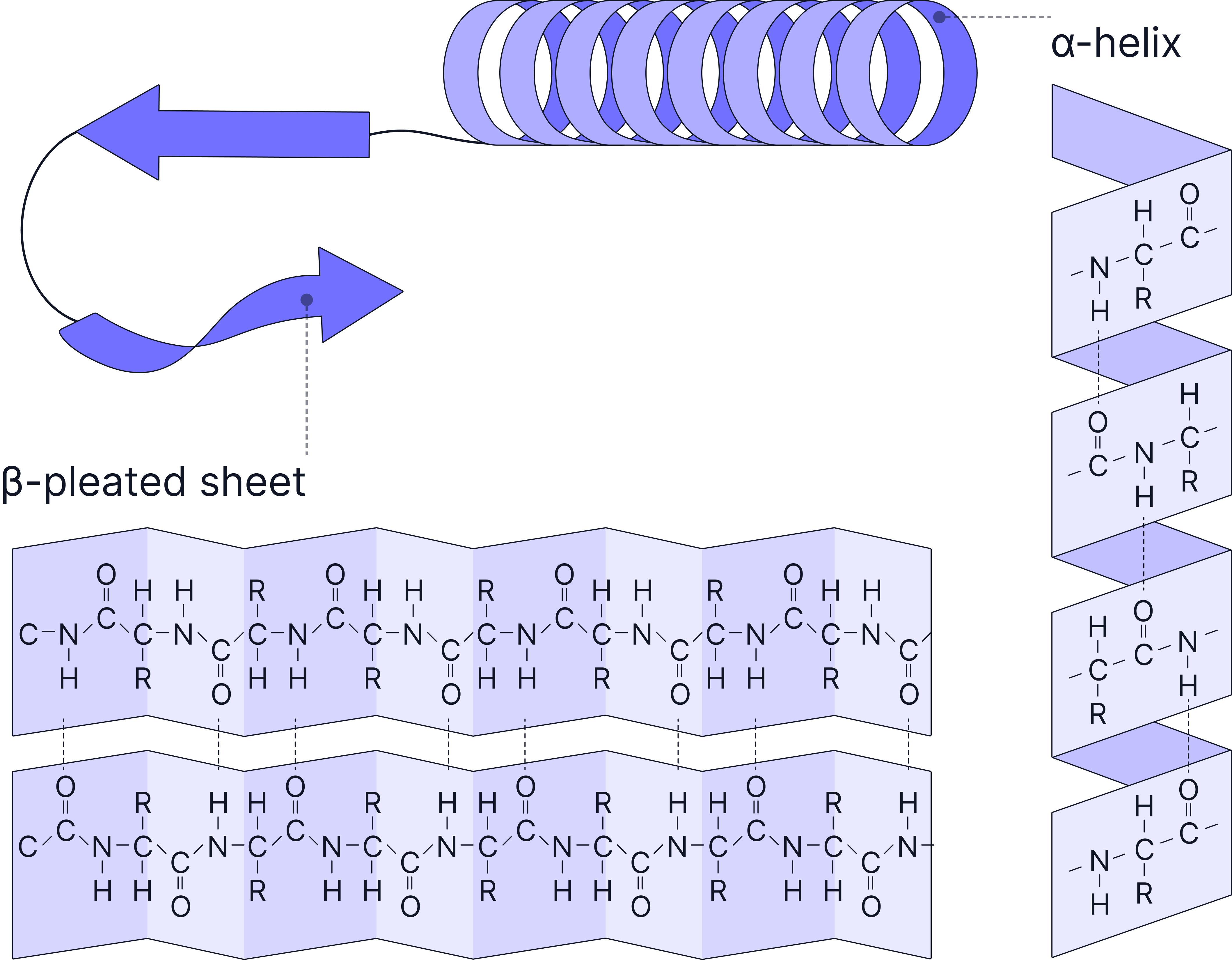

Secondary Structure

Folding or coiling of the polypeptide chain due to hydrogen bonding.

Hydrogen bonds form between the C=O and N-H groups within the polypeptide backbone.

Common structures include the alpha helix (α-helix) and beta pleated sheet (β-sheet).

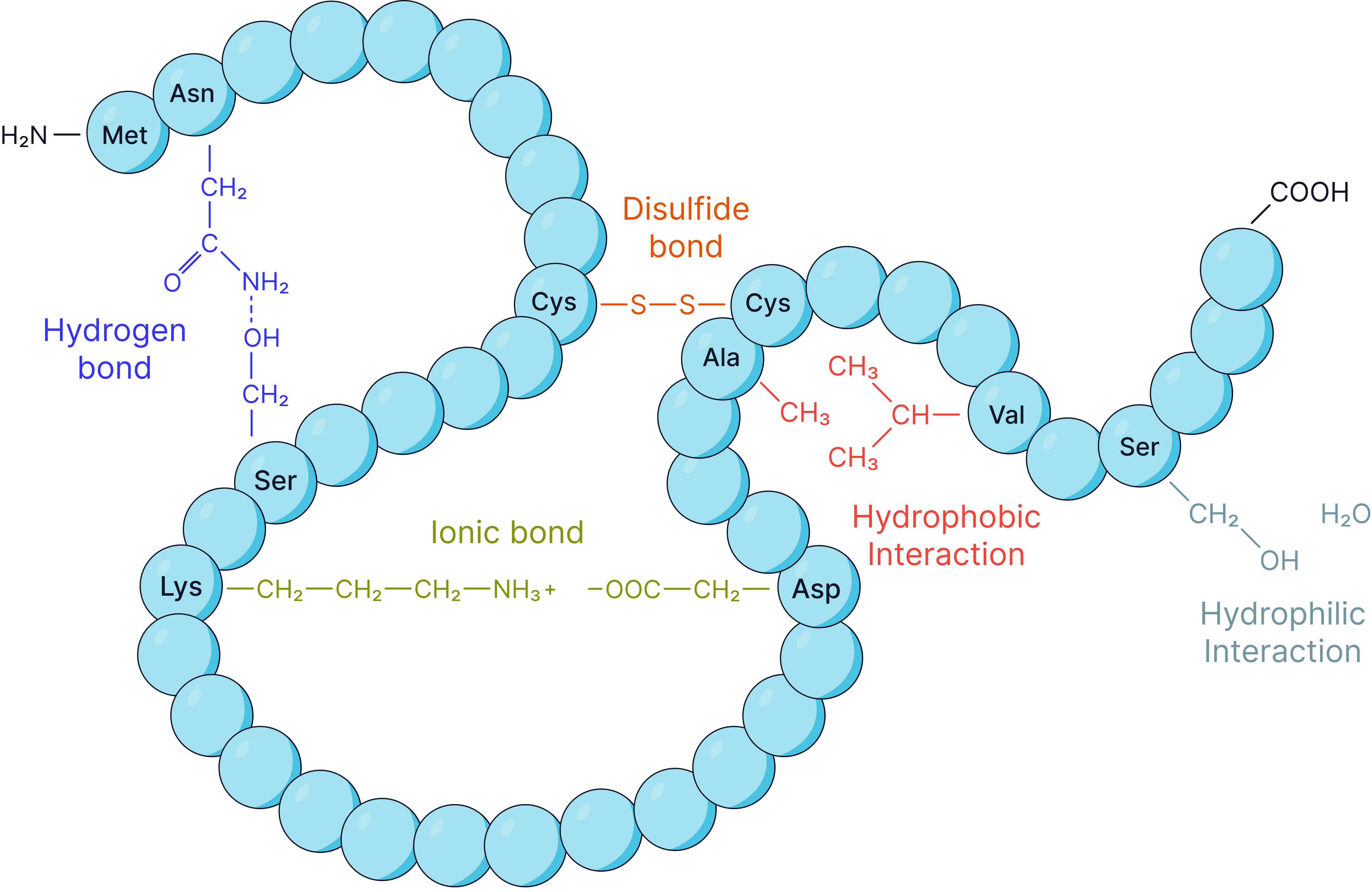

Tertiary Structure

Further folding and coiling due to interactions between R groups, including hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds and disulphide bonds (strong, covalent bonds between cysteine residues) that typically do not break when a protein is denatured.

This structure determines the protein’s specific 3D shape and specific functional properties.

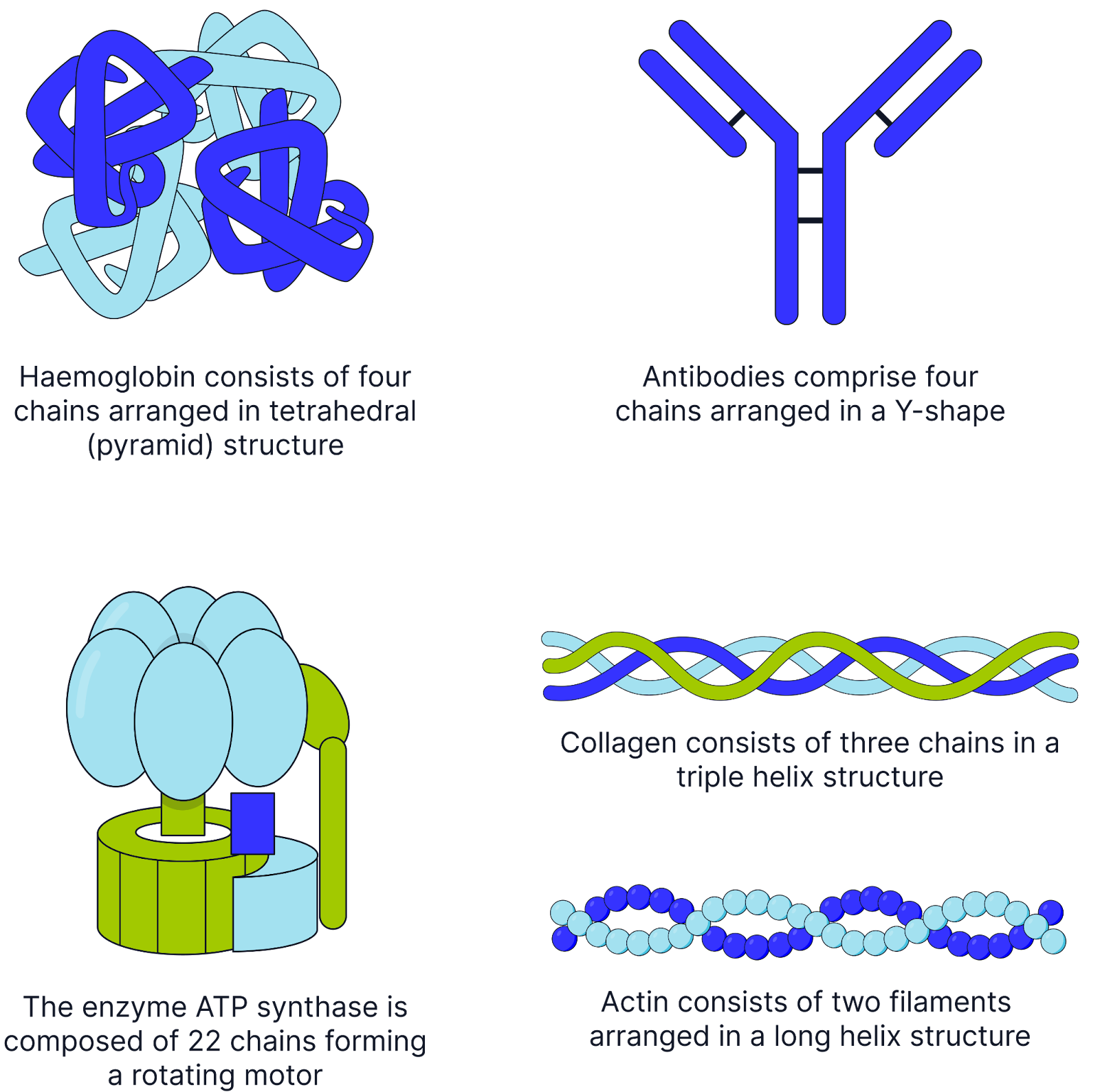

Quaternary Structure

A Protein structure consisting of two or more polypeptide chains

It may also include non-protein groups.

Examples include haemoglobin, which consists of four polypeptide chains and the non-protein haem groups.

Enzymes

Structure:

They are globular proteins with a specific 3D tertiary structure determined by their amino acid sequence.

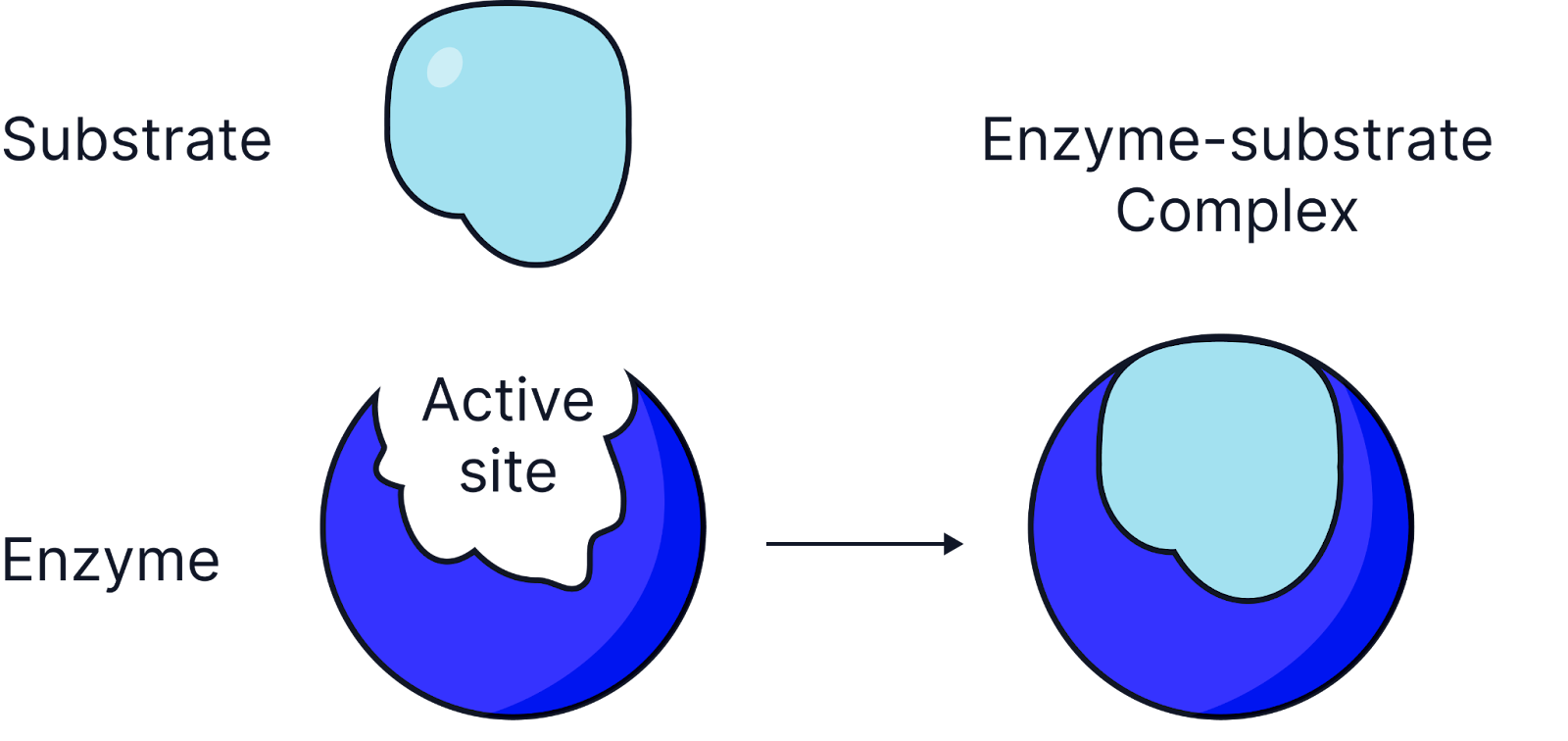

Formation of Enzyme-Substrate Complex:

The specific substrate binds to the enzyme’s complementary active site.

Lowering of Activation Energy:

Enzymes strain bonds in the substrate, lowering the activation energy making the reaction more likely to occur. This allows biochemical reactions to take place at much lower temperatures and therefore increase the rate of reaction.

Product Formation:

The substrate is converted into the product, which then leaves the active site.

Enzyme Reusability:

Enzymes are biological catalysts that speed up metabolic reactions, remaining unchanged, catalysing more reactions.

Active site

The specific region where the substrate binds.

Enzyme-substrate complex

A temporary structure formed when the enzyme binds to the substrate.

Activation energy

The minimum energy required for a reaction to occur.

Lock and Key Model

The active site is complementary to one substrate

The substrate fits into the enzyme's active site exactly, like a key in a lock.

The enzyme remains unchanged after the reaction.

This model is now considered too simplistic as it does not explain flexibility in the active site or how the activation energy of the reaction is reduced.

Induced Fit Model

The active site is not a perfect fit initially but changes shape slightly when the substrate binds.

This leads to tighter binding and strains the bonds in the substrate, lowering activation energy. (alternatively reactants are held closer together overcoming any repulsive forces, lowering the activation energy)

This model better explains how enzymes work in real biological systems.

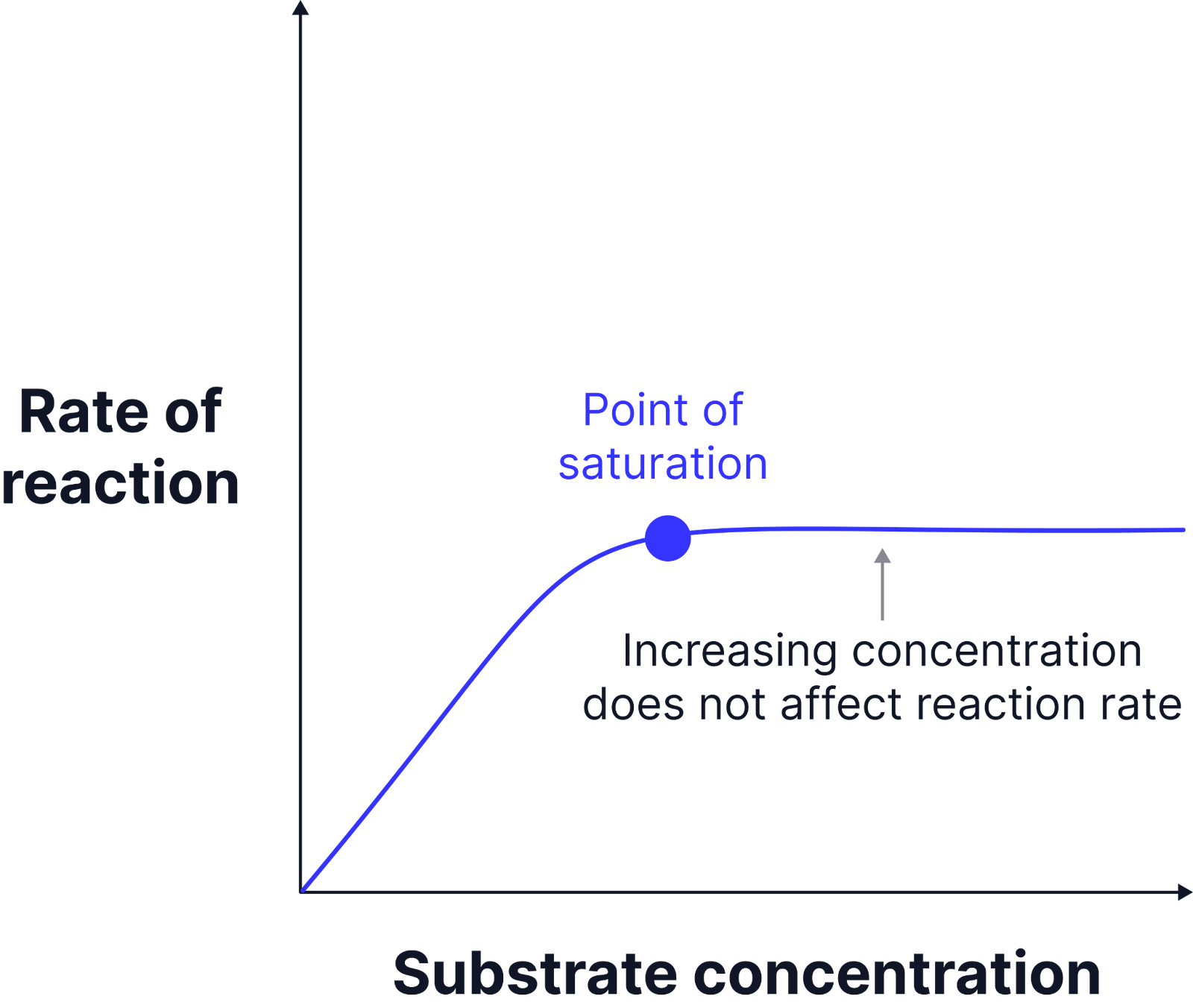

Saturation Point

When all active sites are occupied; increasing substrate further does not increase the reaction rate.

Vmax

Maximum rate of reaction when an enzyme is fully saturated with substrate/ all active sites are occupied.

Limiting Factor - Substrate Concentration

Increasing substrate concentration has a linear increase of initial reaction rate as more enzyme-substrate complexes form.

When the saturation point is reached, the line plateaus and the enzyme is operating at the maximum rate of reaction, know as Vmax. All active sites are occupied, no more enzyme substrate complexes form.

If no substrate is added to a reaction mixture, amount of substrate decreases, converting into products. Rate of reaction will decrease over time as less substrate is available to form enzyme-substrate complexes.

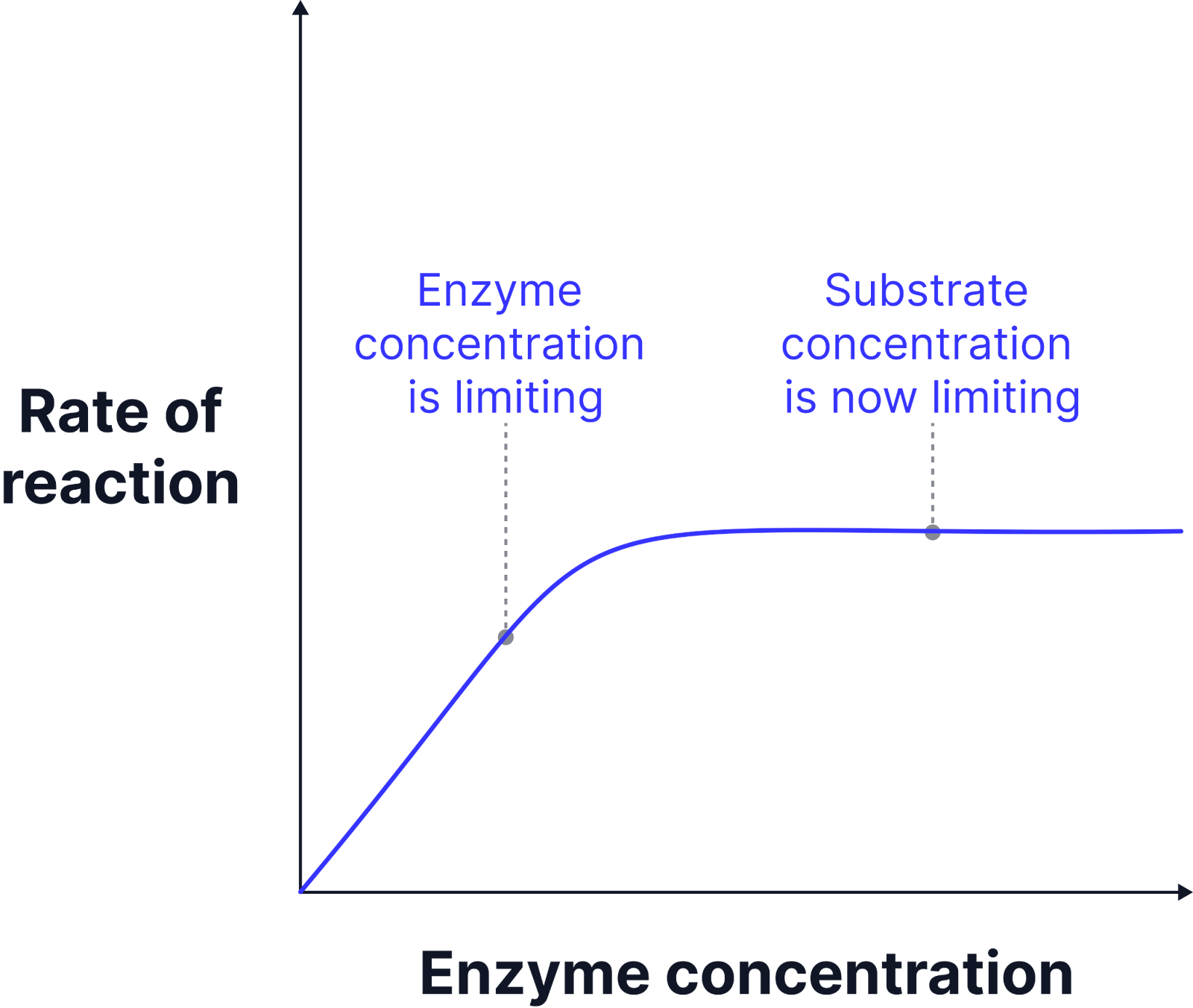

Limiting Factor - Enzyme Concentration

Higher enzyme concentration provides more active sites, increasing the chances of enzyme-substrate complex formation.

When sufficient substrate is available, the initial reaction rate rises linearly with increasing enzyme concentration.

If substrate is limited, increasing enzyme concentration beyond a certain point will not increase the reaction rate, as substrate availability becomes the limiting factor.

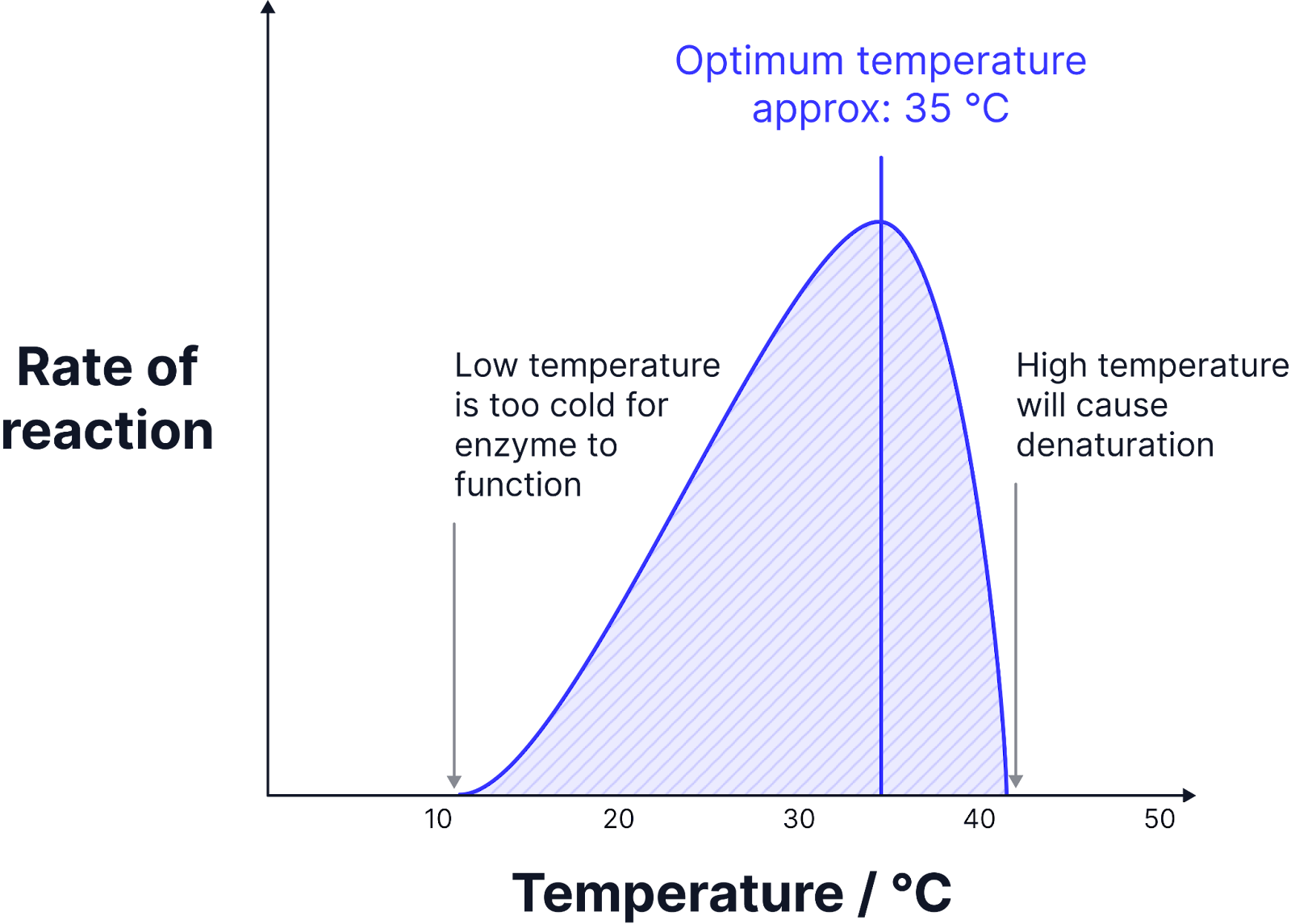

Limiting Factor - Temperature

As temperature increases the rate of reaction increases. The substrate particles and enzymes gain more kinetic energy, so move faster, and collide more frequently.

This results in more enzymes substrate complexes forming and a faster reaction rate, up to the optimum temperature.

The optimum temperature is the temperature at which the enzyme rate of reaction is at its maximum.

Above the optimum temperature the rate of reaction decreases. The bonds that hold the tertiary structure of the enzyme start to vibrate more and break, changing it.

The active site will have changed shape and is no longer complementary to the substrate.

The enzyme has denatured and enzyme-substrate complexes cannot form.

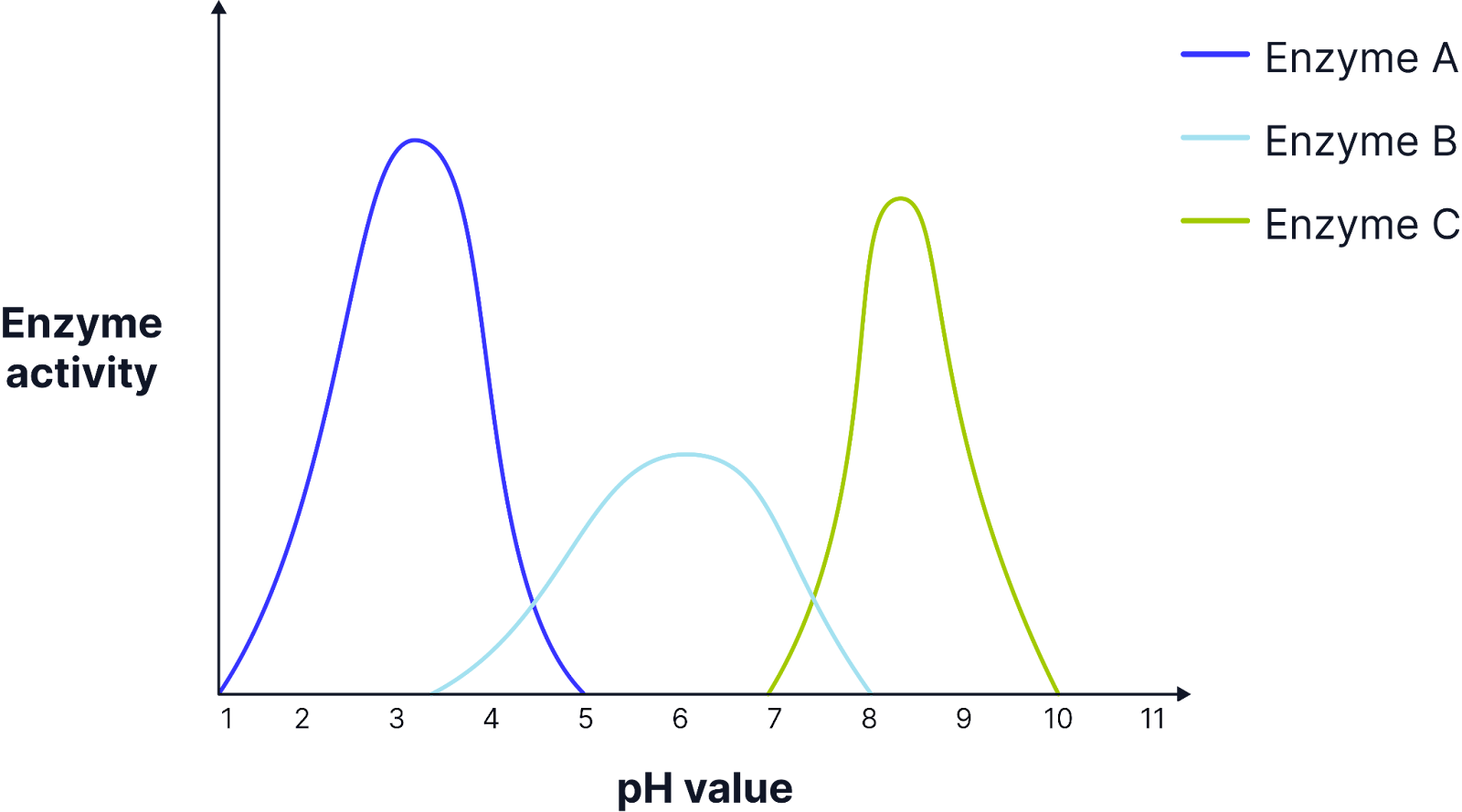

Limiting Factor - pH

Enzymes are denatured at anything higher or lower than the optimum pH.

The excess of H+ and OH- in solution disrupts and breaks hydrogen and ionic bonds in the tertiary structure of the enzymes and denatures the enzyme.

The active site is no longer complementary to the substrate and no enzyme substrate complexes form.

Different enzymes will have a different optimum pH. The optimum pH for a protease, pepsin, is a pH of 2 because it is secreted in the stomach.

Some enzymes may be adapted to function over a wider range of pH values. For example, in the case of bacteria this could mean that they are more tolerant to changes in the environment.

When investigating the effect of pH on the action of enzymes a buffer solution can be used. This is very important if the products of the enzyme controlled reaction would lead to a pH change.

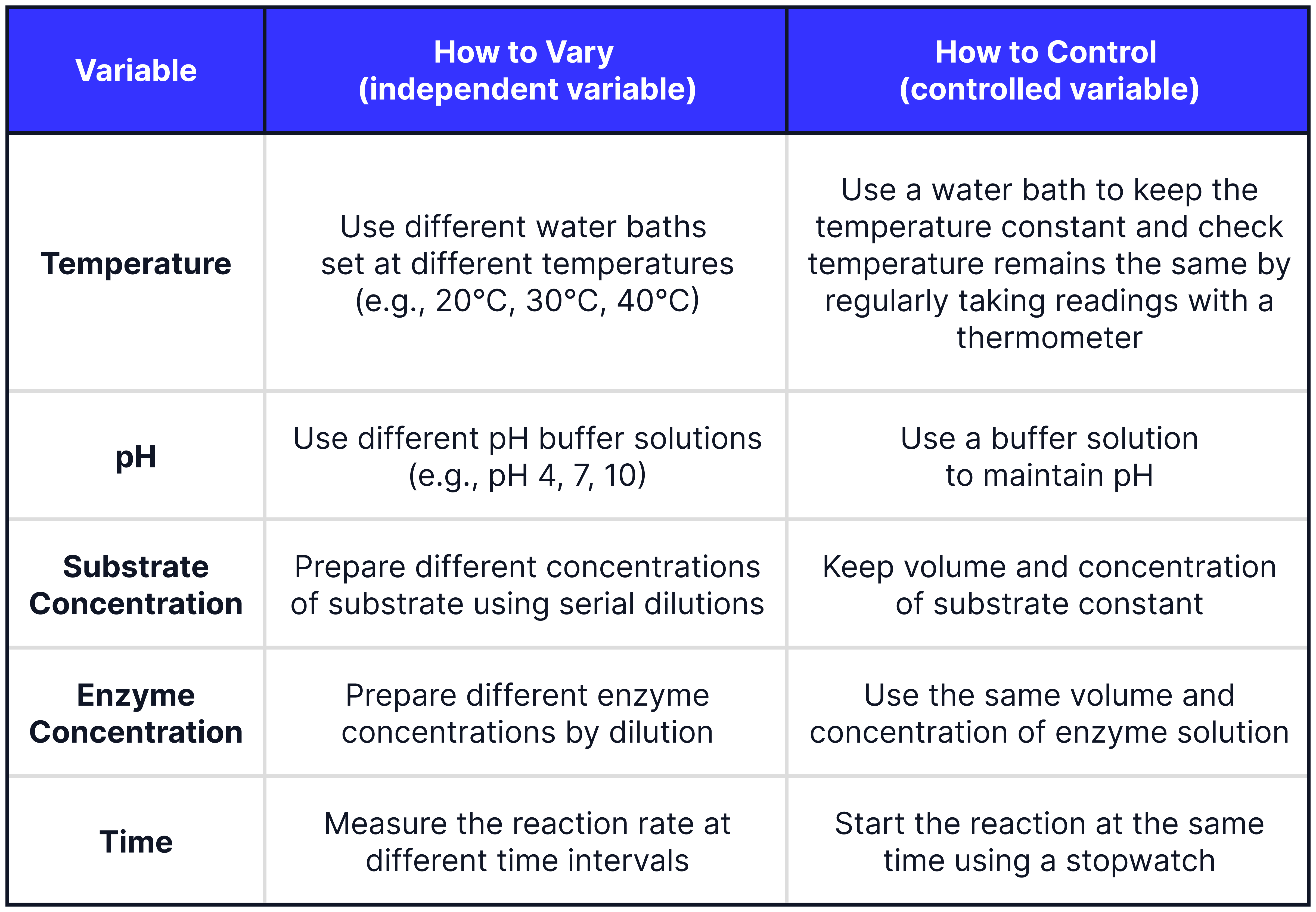

Controlling and Varying Variables

To plot a graph and observe a trend, you need at least 5 different values for your independent variable.

When investigating the effect of temperature make sure that the enzyme and substrate solutions are at the same temperature. Place them into the water bath for sufficient time to allow them to equilibrate before mixing.

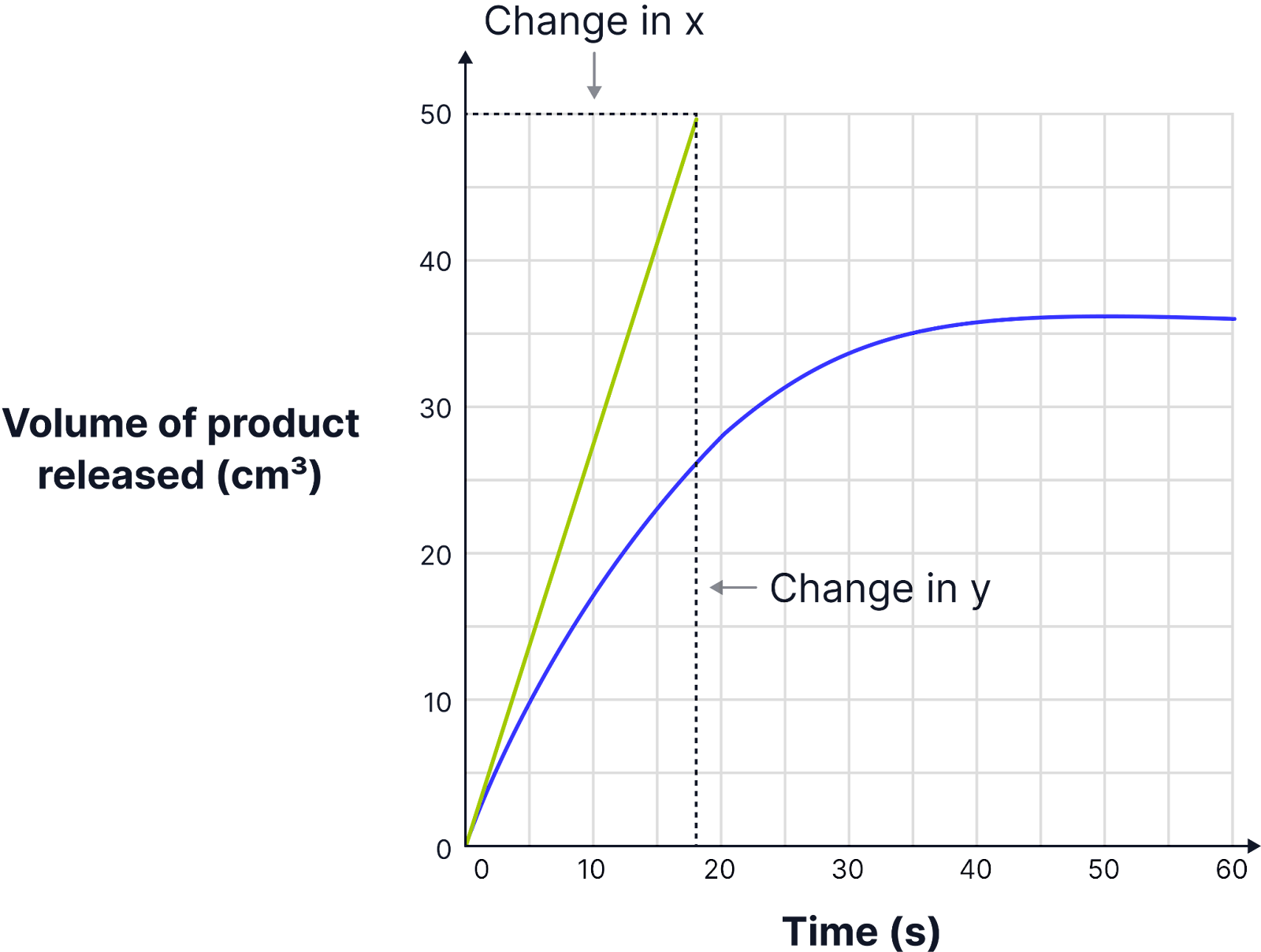

How to plot results on a graph for the Initial Rate of Reaction

X-axis: Time (seconds)

Y-axis: Volume of oxygen produced (cm³)

Plot the data points and draw a smooth curve (not a straight line).

How to Determine the Initial Rate of Reaction

The rate of reaction decreases over time as the substrate is used up so we need to find the initial rate of reaction to be able to compare.

The initial rate of reaction is the rate at the very start of the reaction when substrate concentration is highest.

To find this:

Draw a tangent at t = 0 on the curve.

Calculate the gradient of the tangent: Rate=change in y ÷ change in x

E.g. Rate = 50.0 ÷ 18.0 = 2.778 cm³s⁻¹

Active site

The region on the enzyme where the substrate binds.

Denaturation

Loss of enzyme structure due to high temperature or extreme pH.

Substrate concentration

The amount of substrate available for the enzyme to act upon.

Enzyme concentration

The number of enzyme molecules available for catalysis.

Tangent

A straight line touching the curve at one point, used to estimate initial rate.

Enzyme inhibitor

A substance that reduces or stops the rate of enzyme-controlled reactions by interfering with enzyme activity.

There are two main types, competitive inhibitors and non-competitive inhibitors

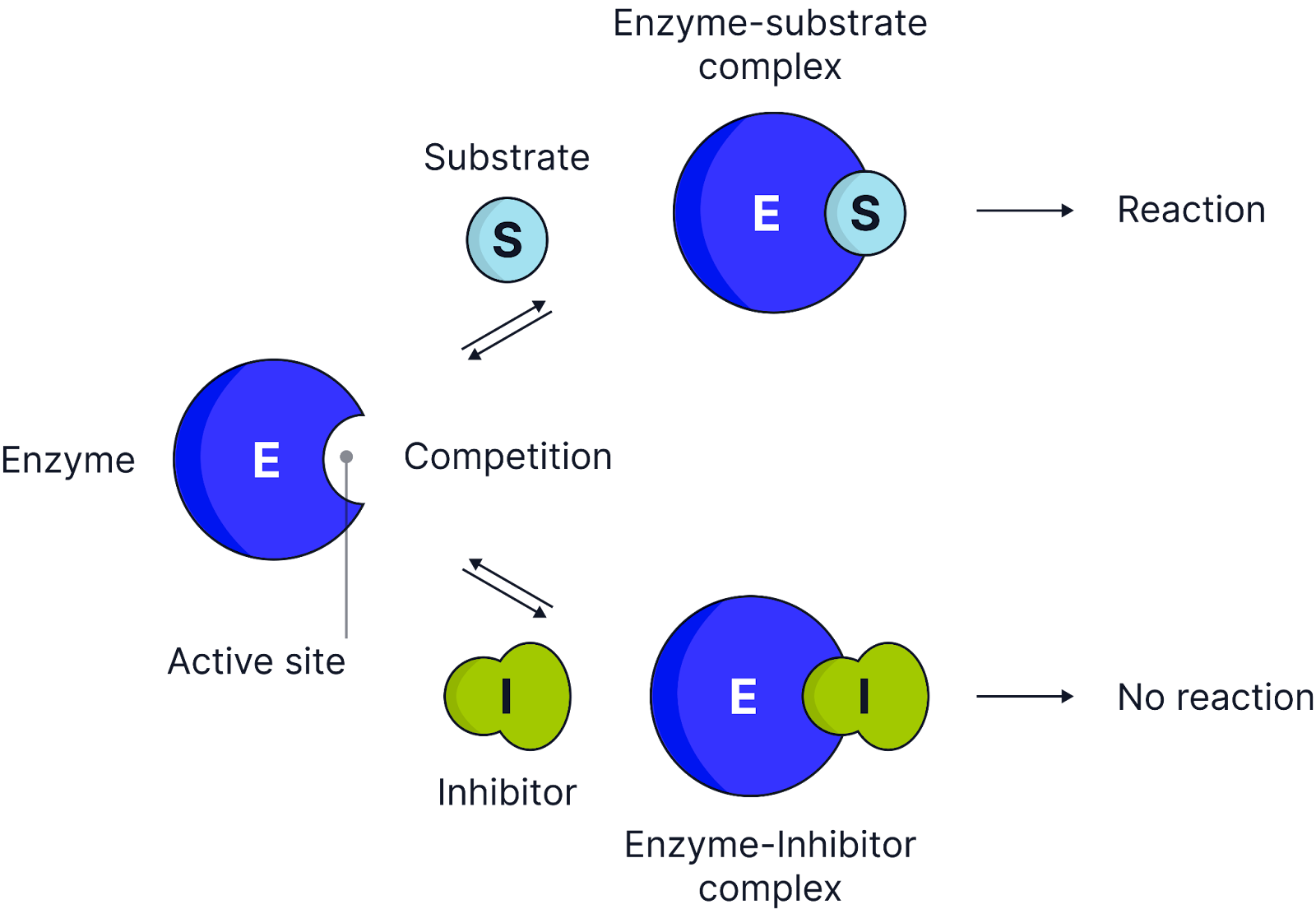

Competitive inhibitor

How they work:

Have a similar shape to the substrate and compete for the active site.

They bind temporarily to the active site, preventing the substrate from binding, reducing the number of enzyme-substrate complexes formed.

Effect on reaction rate:

Increasing substrate concentration reduces the effect of a competitive inhibitor.

At high substrate concentrations, the reaction reaches Vmax as more substrate molecules outcompete the inhibitor since enzyme substrate complexes form and fewer enzyme inhibitor complexes will form.

Malonate inhibits succinate dehydrogenase, an enzyme used during the Krebs cycle in aerobic respiration.

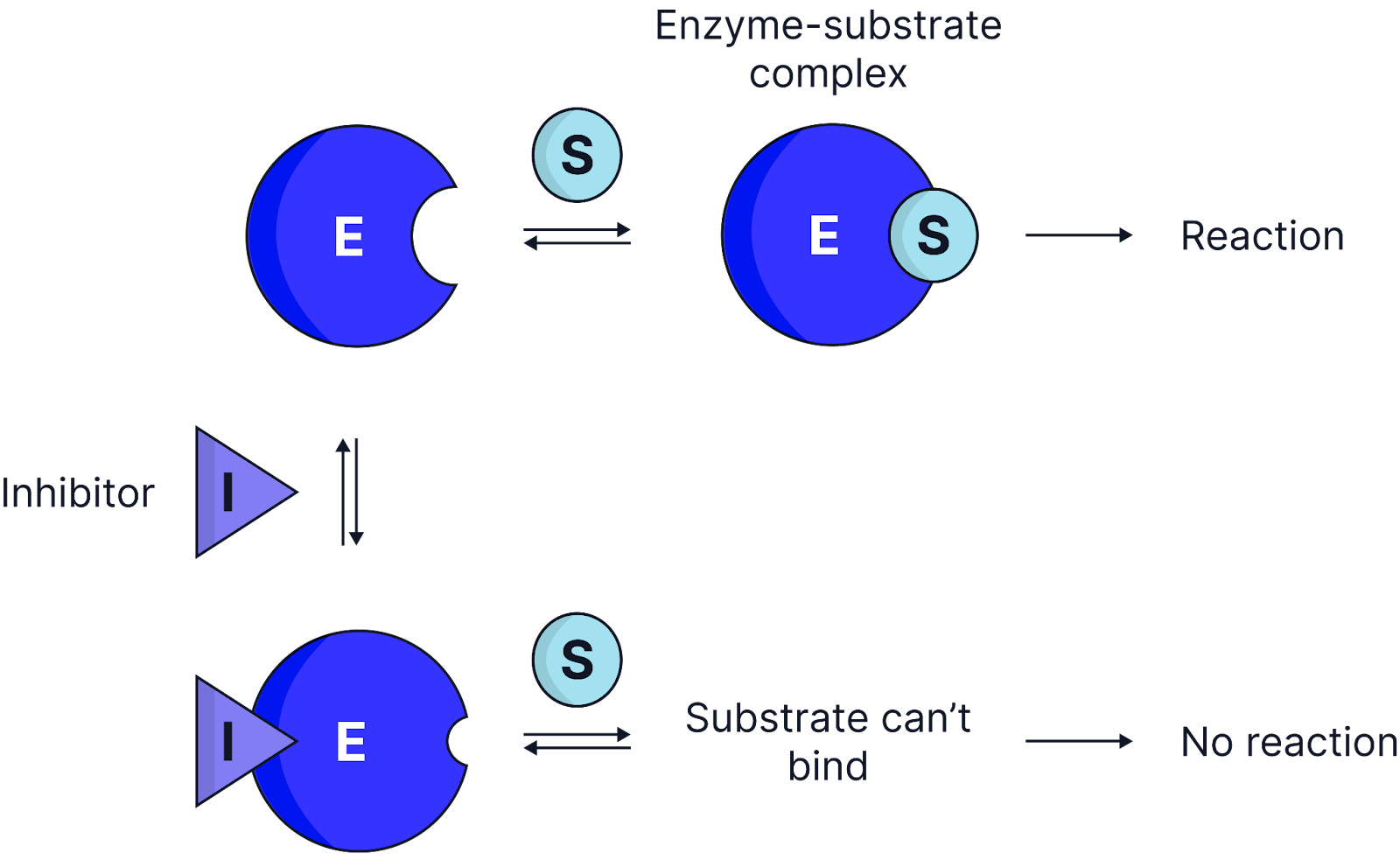

Non-competitive inhibitor

How they work:

Non-competitive inhibitors bind to an allosteric site (a site other than the active site) on an enzyme, altering the enzyme’s tertiary structure, changing the shape of the active site so the substrate can no longer bind to the active site, preventing enzyme-substrate complexes from forming.

Effect on reaction rate:

Increasing substrate concentration does not reduce the inhibitor’s effect because the substrate is not in competition with the inhibitor for the enzyme's active site.

No matter how high the concentration of substate, some enzymes will always be inhibited by the non-competitive inhibitor.

Example: Cyanide inhibits cytochrome c oxidase, an enzyme used in oxidative phosphorylation during aerobic respiration.

Recognising Inhibitor Type in a Rate vs. Substrate Concentration Experiment

Competitive inhibition:

As substrate concentration increases, Vmax is eventually reached because the inhibitor can be outcompeted.

Non-competitive inhibition:

Increasing substrate concentration does not allow Vmax to be reached because enzyme molecules are permanently altered.

Graph interpretation:

Competitive inhibitors: The reaction rate gradually increases, approaching Vmax at high substrate concentrations.

Non-competitive inhibitors: The reaction rate plateaus at a lower level, as fewer active sites are available.

Enzyme inhibitor

A substance that slows or stops an enzyme-controlled reaction.

Allosteric site

A secondary binding site on an enzyme where non-competitive inhibitors attach.

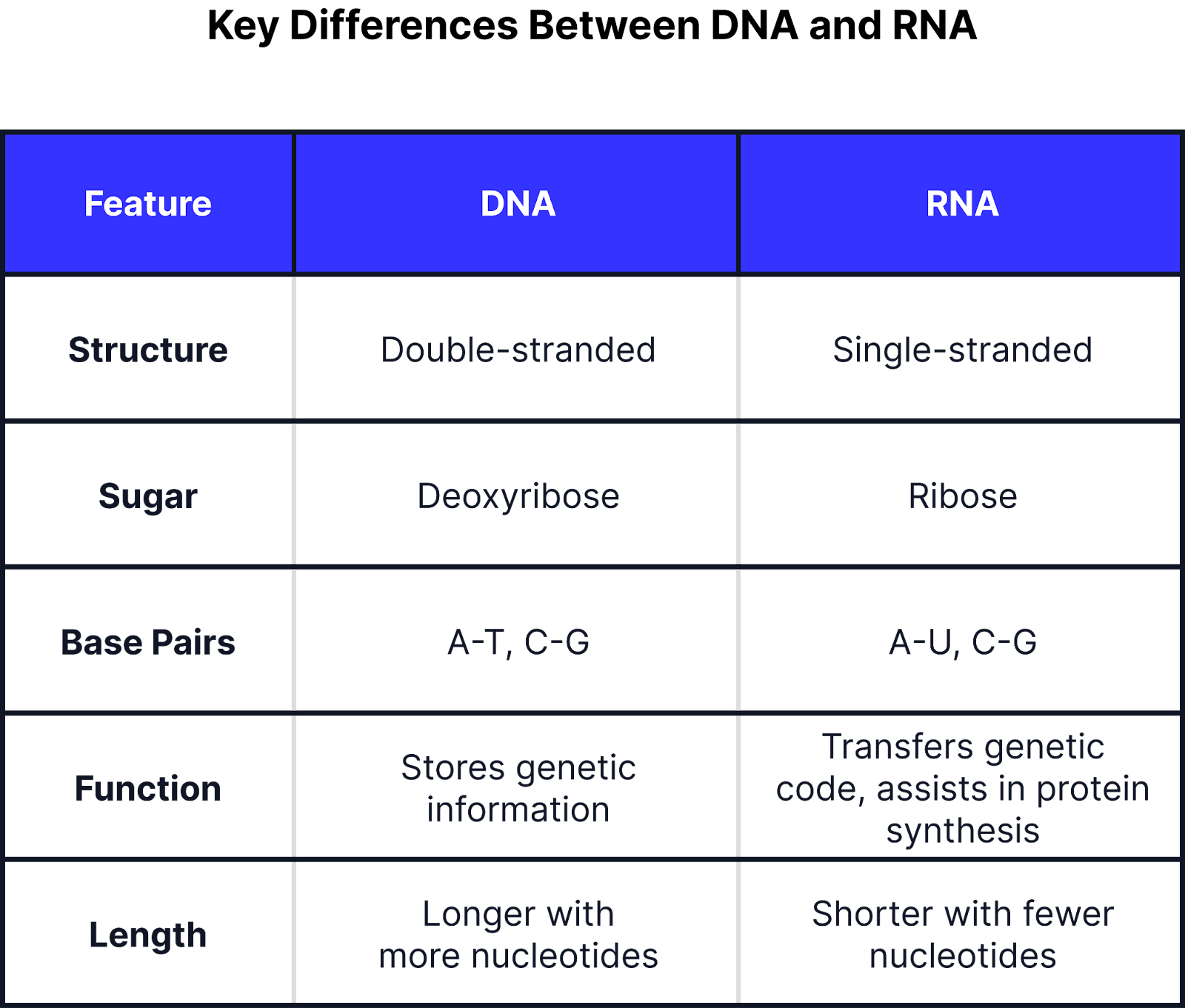

Nucleic acids

Encode the genetic instructions for protein synthesis. The universality of the genetic code among all living organisms, including viruses, further supports the theory of evolution.

Monomer: nucleotides

Polymer: DNA / RNA

Condensation bond: phosphodiester bonds

Hydrolysis enzyme:

Elements: carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and phosphorus

Key components: pentose sugar (deoxyribose and ribose), phosphate group and a nitrogenous base (A, T, C, G and U).

Nucleotide

The monomer of nucleic acids, consisting of a phosphate group, pentose sugar, and nitrogenous base.

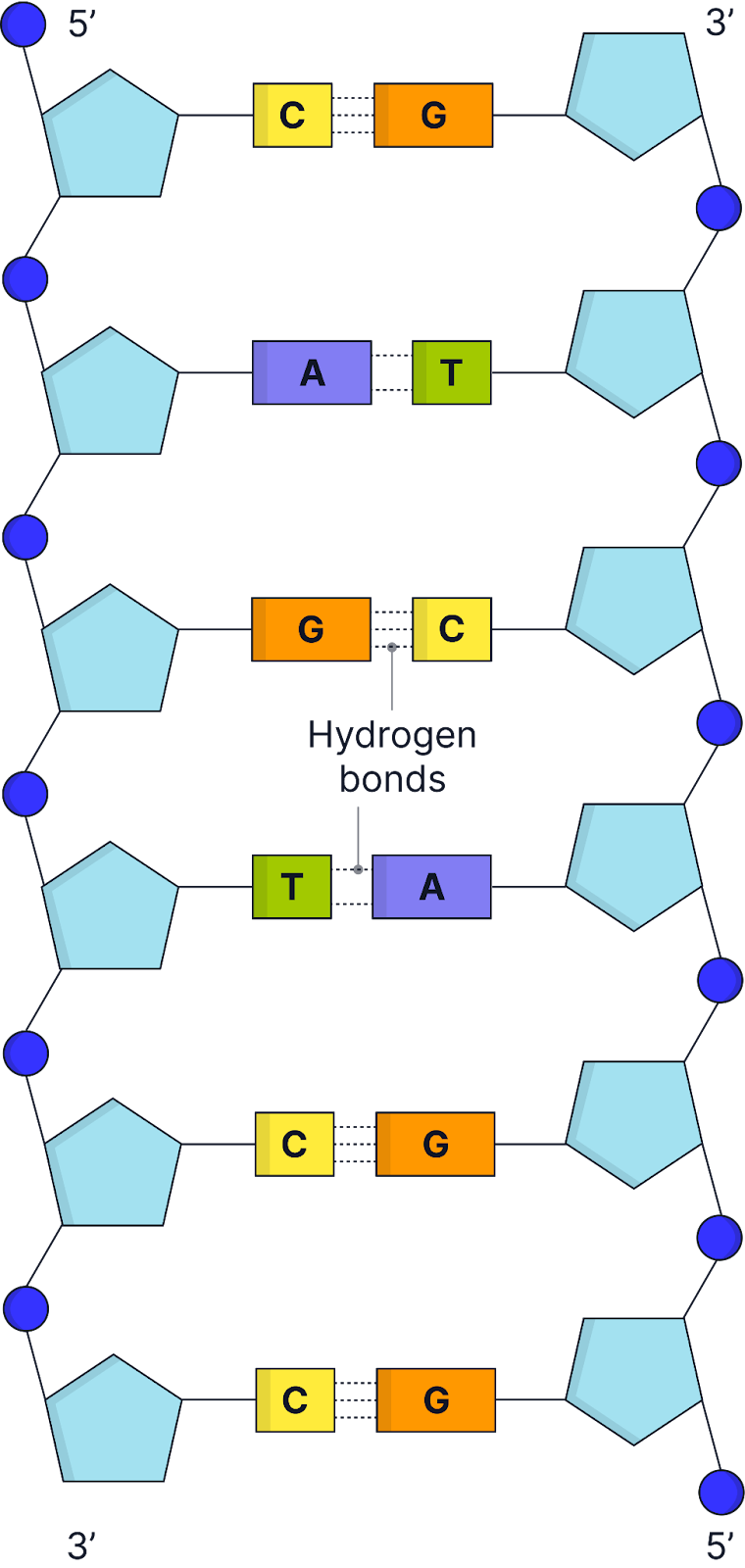

Complementary base pairing

A-T (DNA), A-U (RNA), C-G pairing with hydrogen bonds.

Antiparallel

DNA strands run in opposite directions (5' to 3' and 3' to 5'). This refers to the carbon number on the deoxyribose sugar.

Phosphodiester Bond

The bond linking nucleotides, forming the sugar-phosphate backbone.

Double Helix

The spiral structure of DNA, discovered by Watson and Crick.

DNA

DNA nucleotides contain a phosphate group, deoxyribose sugar and nitrogenous base (A+T with 2 H-bonds, G+C with 3 H-bonds)

Nucleotides join through phosphodiester bonds, formed by condensation reactions between phosphates and deoxyribose sugar of adjacent nucleotides, forming a sugar-phosphate backbone, which provides structural stability.

Has a double helix structure composed of 2 polynucleotide chains joined by hydrogen bonding between nitrogenous bases - pairing ensures accurate replication and stability of DNA

The two DNA strands run antiparallel (opposite directions). One strand is 5’ to 3’, and the other is 3’ to 5’

Stable due to the strong, covalent phosphodiester bonds in the sugar-phosphate backbone.

Complementary base pairing allows for accurate replication.

Hydrogen bonds between bases allow easy strand separation for replication and transcription.

Compact structure fits inside the nucleus while storing a vast amount of genetic information.

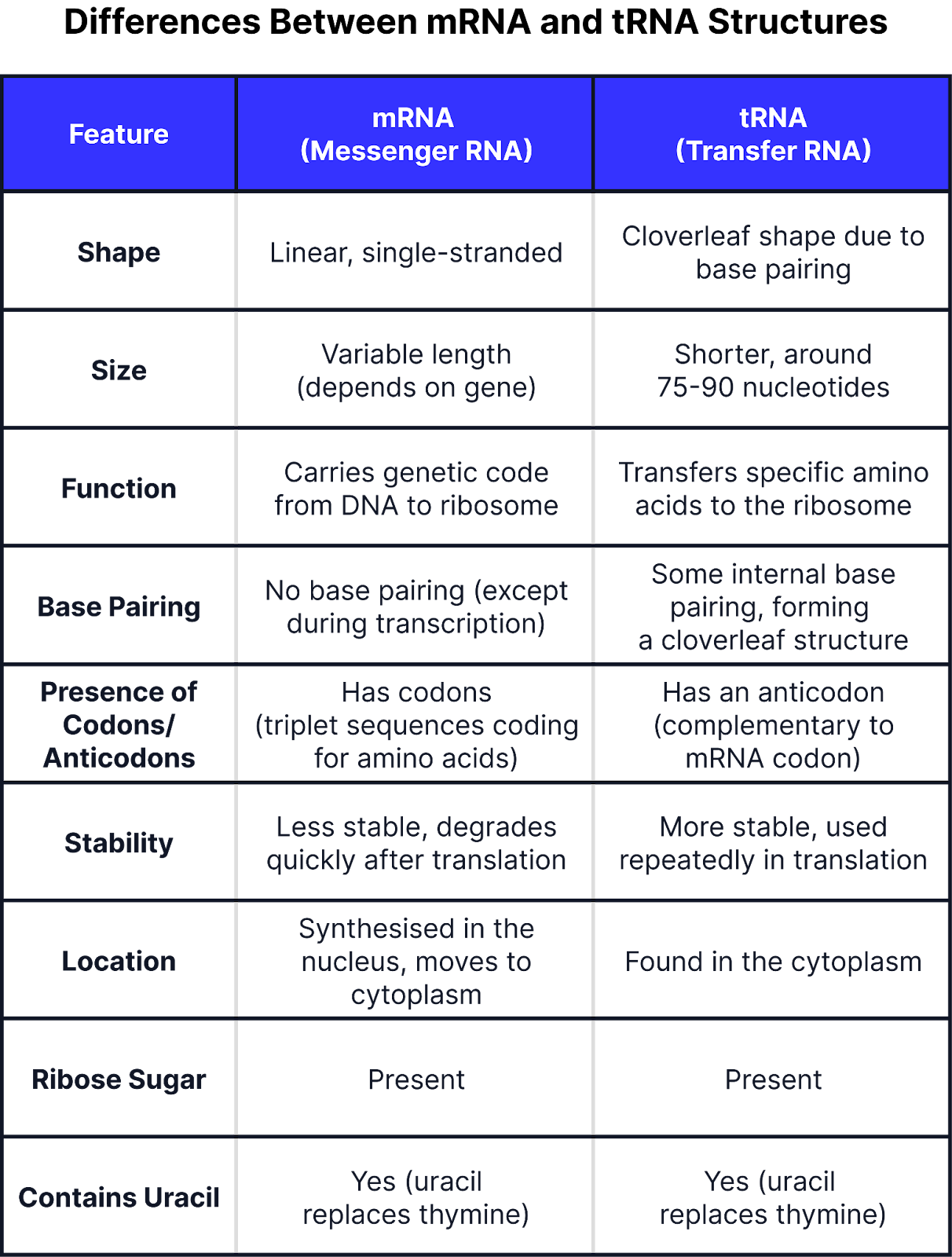

DNA vs RNA

messenger RNA

Carries the genetic code from DNA to the ribosome.

Single-stranded and varies in length depending on the gene being expressed.

mRNA is linear so there are no complementary base pairs or hydrogen bonds within the mRNA molecule itself.

Has codons (sets of 3 bases which code for a specific amino acid.

ribosomal RNA

Forms part of the ribosome structure (along with protein)

transfer RNA

Brings specific amino acids to the ribosome during translation.

Folded, cloverleaf shape held together by complementary base pairs and hydrogen bonds.

Has an anticodon that pairs with mRNA codons.

Has an amino acid binding site.

mRNA vs tRNA

Cell cycle

A series of stages a cell will go through in order to divide and produce two new cells.

DNA helicase

An enzyme used in DNA replication. It breaks the hydrogen bonds between complementary bases to separate the two strands.

DNA polymerase

An enzymes used in DNA replication. It joins adjacent nucleotides together by making phosphodiester bonds in condensation reactions. This requires ATP.

Semi-conservative replication

The DNA molecules made in DNA replication will contain one of the original, parent strands and one newly synthesised strand.

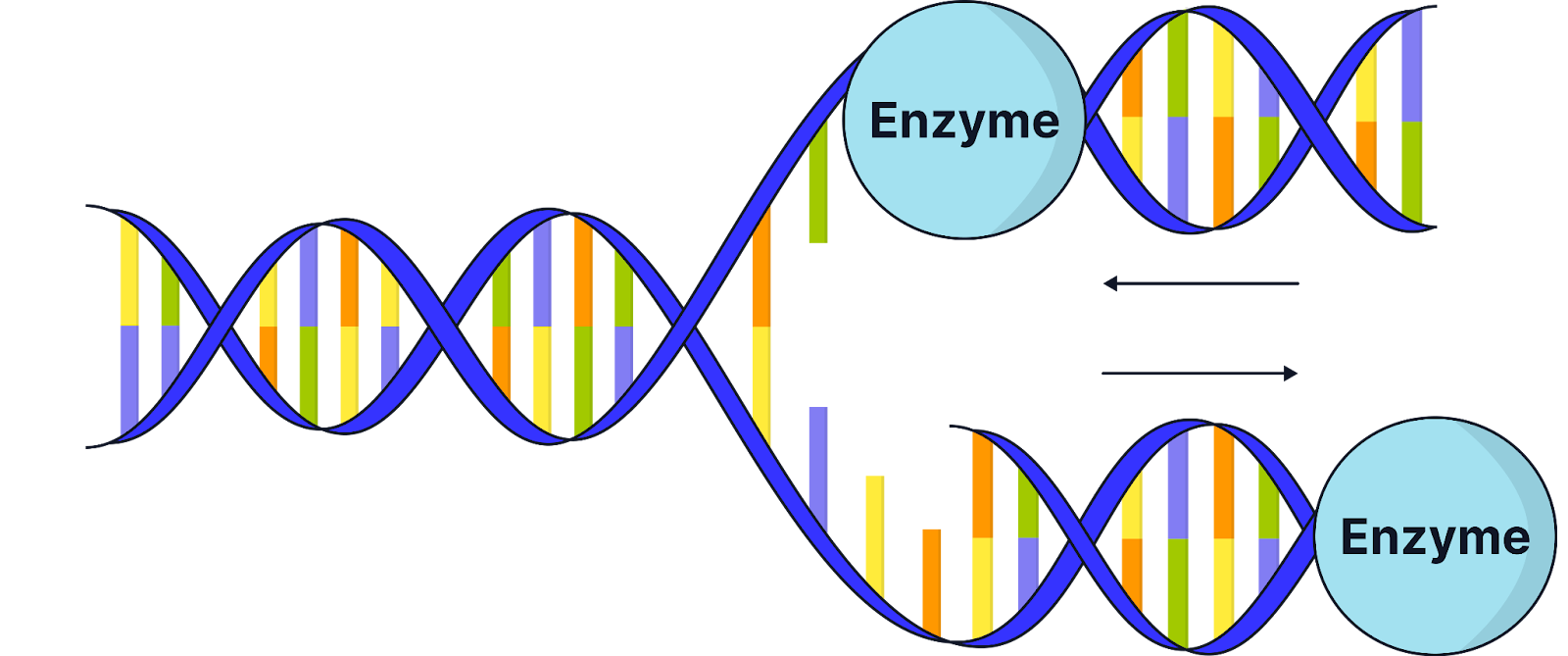

DNA replication

DNA is replicated during interphase of the cell cycle.

1. DNA helicase breaks hydrogen bonds between the complementary bases.

2. This separates the two strands.

3. Both strands then act as templates.

4. Free nucleotides line up with the template strands according to the base pair rule.

5. Adenine pairs with thymine and cytosine pairs with guanine.

6. DNA polymerase joins adjacent nucleotides together by making phosphodiester bonds in condensation reactions. This requires ATP.

7. DNA replication is described as semi-conservative replication. This is because the DNA molecules formed each contain 1 original strand and 1 new strand.

1. What is the job of DNA Helicase?

It breaks the hydrogen bonds between the bases to separate the two strands.

2. What is the job of DNA polymerase?

It joins adjacent nucleotides together by making phosphodiester bonds.

3. If an inhibitor of DNA polymerase were introduced into a cell, what would be the effect on cell division?

Cell division would stop as DNA replication cannot occur.

This is because DNA polymerase cannot join nucleotides together and the new DNA strands will not form.

4. Why does DNA polymerase move in opposite directions along the two strands?

The two strands in DNA are antiparallel (they run in opposite directions). DNA polymerase is an enzyme with a specific tertiary structure and a specifically shaped active site. It can only attach new nucleotides at the 3’ end of a DNA nucleotide. This means it can only move in the 5’ to 3’ direction.

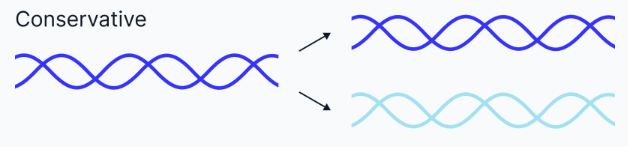

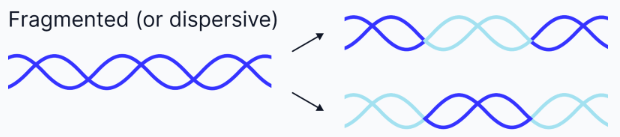

Conservative replication

One entirely new DNA molecule is made, and the original remains intact.

Semi-conservative replication

Each new DNA molecule consists of one old strand and one new strand.

Fragmented or Dispersive replication

DNA strands are mixtures of old and new DNA.

Isotope

Different forms of an element with the same number of protons but a different number of neutrons.

Nitrogen-15 (15N)

A heavy isotope of nitrogen used to label DNA in the experiment.

Nitrogen-14 (14N)

A lighter isotope of nitrogen used in the second stage of the experiment.

Centrifugation

A process that separates DNA by density using a high-speed spinning force.

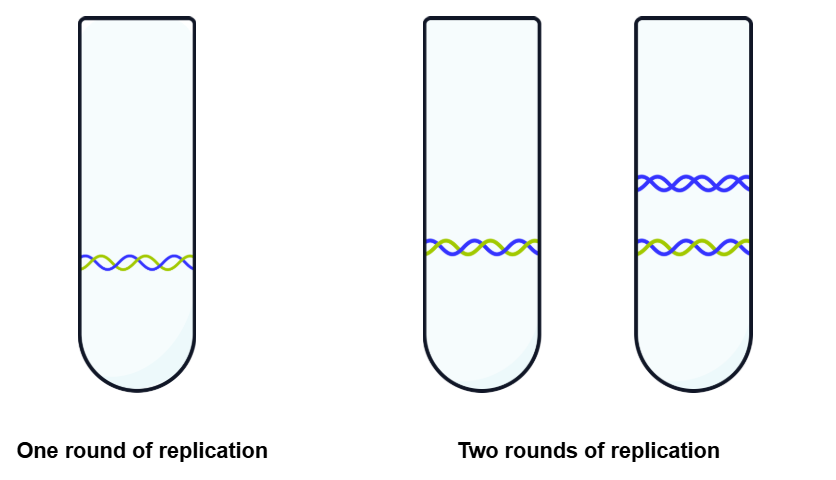

Meselson and Stahl (1958) Experiment Steps

Growing Bacteria in Heavy Nitrogen (15N):

E. coli was first grown in a medium containing only the heavy isotope of nitrogen (15N), which was incorporated into their DNA. This made the DNA denser.

Switching to Light Nitrogen (14N):

Bacteria were then transferred to a medium containing only the lighter isotope of nitrogen (14N) and allowed to replicate once.

Centrifugation to Analyse DNA Density:

DNA was extracted and centrifuged to observe its position in the test tube. It does this by spinning the extracted DNA at high speed. Causing the DNA to collect in different areas, depending on the density.

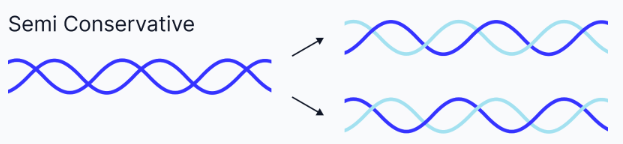

Meselson and Stahl (1958) Experiment Findings

After one round of replication in 14N:

DNA formed a single intermediate band in the centrifuge tube.

This disproved the conservative model, as there was no fully light (14N) or fully heavy (15N) DNA.

This supported the semi-conservative replication model, as the DNA consisted of one original (15N) strand and one newly synthesised (14N) strand.

After two rounds of replication in 14N:

Two distinct bands were observed

One intermediate density consisting of one original (15N) strand and one newly synthesised (14N) strand.

One less dense band that consisted of two strands containing 14N.

Final Conclusion:

The experiment provided strong evidence that DNA replication occurs via the semi-conservative model.

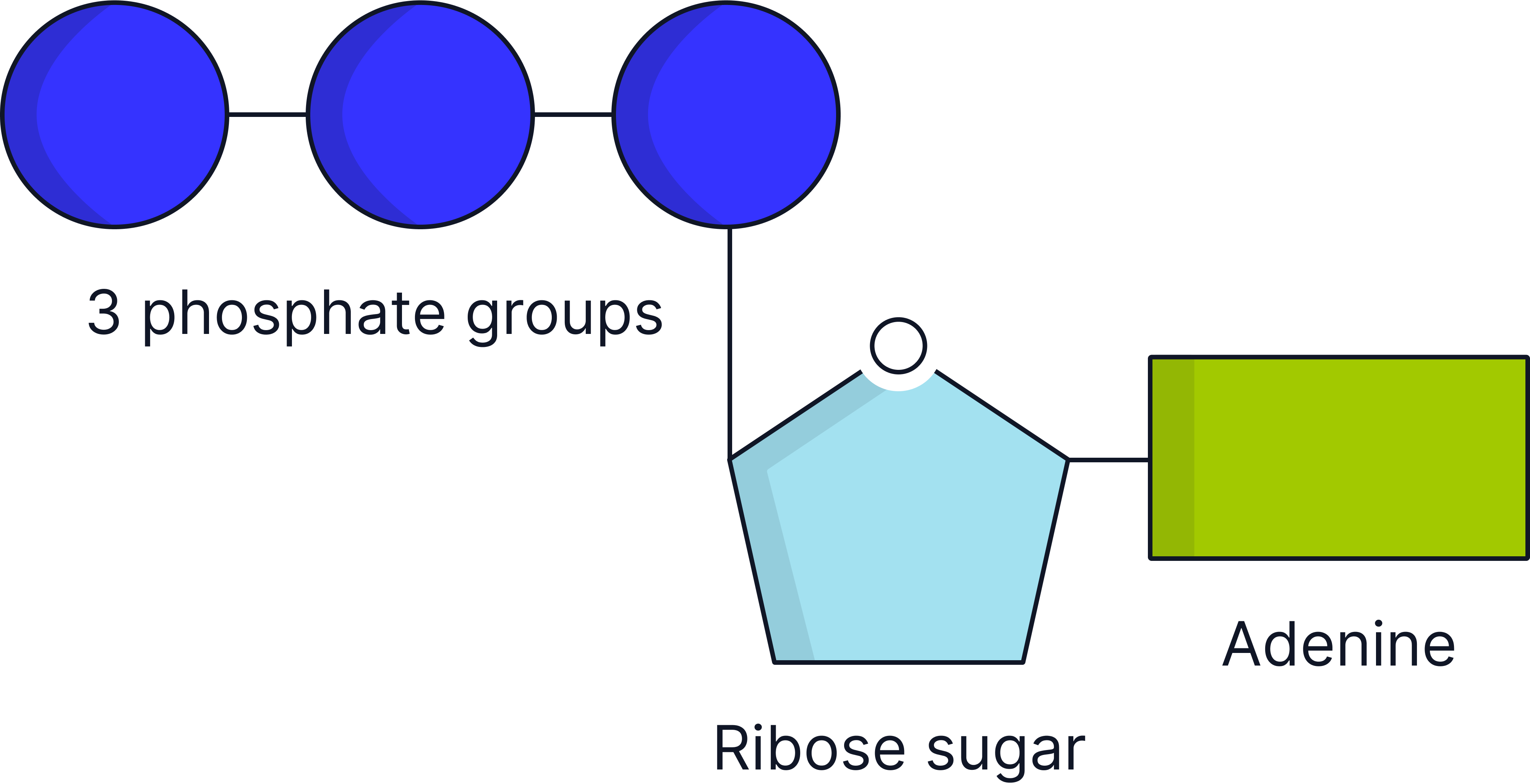

ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate)

A nucleotide derivative that transfers energy in cells.

ATP is a nucleotide derivative composed of Adenine (nitrogenous base), Ribose (a pentose sugar) and three Phosphate groups (key to energy storage and release).