Pathophysiology Exam 4 Flashcards

1/74

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

75 Terms

What is pericarditis?

Pericardial inflammation, which is the area of the heart that envelops it; a sac filled with serous fluid (less than 50cc). This is the area between the parietal/outer, and visceral/inner pericardial walls. Most are acute, few can produce chronic reactions. This can cause pleural effusion, which causes excess fluid in this space (acute, emergency). It can also displace preload, stroke volume, lower QRS. Can be acute (confused with angina, friction of pericardial layers) or chronic (healing of acute forms). Used to happen after MI, but treatment makes it less likely.

Causes include: Infectious agents (virus, bacteria, fungi, parasites), immunology (rheumatic fever, lupus, hypersensitivity), and other causes (MI, uremia, neoplasia, trauma, radiation).

What is pericardial effusion?

The increase of serous fluid in the pericardial cavity of the heart (normal is 30-50m L), which can be filled with blood (hemopericardium) blood and serous fluid (serosanguinous) or pus (purulent pericardium). If fluid accumulation is rapid it can cause cardiac compression (200-300 mL), which is called cardiac tamponade; this displaces the load, restricting the filling of the heart (over 500 mL). If this happens over a gradual period of time, it doesn’t restrict cardiac function. May require drainage to correct.

What is valvular heart disease?

It can be congenital or acquired. Acquired happens due to inflammation (endocarditis), ischemia, trauma, degenerative or infectious agents. This results in abnormal flow, leading to heart murmurs, which are abnormal sounds. If those sounds are severe, you would be able to palpate it.

Stenosis or regurgitation can occur alone or in the same valve. There’s not enough opening and closing. It often involves only one valve (mitral most common) but can be more.

What is the diference btween stenosis and regurgitation?

Diseased valves may have stenosis and/or regurgitation:

Stenosis: The valve does not open completely, obstructing flow. This happens slowly over long periods of time. It’s narrow. The opening of the valve constricts and narrows, often because of calcification, scarring and a primary leaflet abnormality. Can lead to left or right sided heart failure.

Regurgitation: The valve doesn’t open completely, which allows the backflow of blood. This may also be called insufficiency or incompetence. This may lead to prolapse, where the valve fails to close completely and falls out of place. They go into the chamber, going backwards, instead of going up.

The abnormal flow of blood leads to heart murmurs, which are abnormal turbulence.

Artificial valves will be needed because this is permanent. Think about long-term anti-coagulation because of lack of adequate flow. If it’s not completely closed, then you can treat it. Prophylaxis is for endocarditis.

What are some disorders of the mitral valve?

The mitral valve is the bicuspid valve. Open during ventricular diastole, and closed during atrial systole on the left side of the heart.

Mitral Stenosis: Diastolic. Low-pitched rumble at the apex. The blood flow from the left atrium to the ventricle is impaired, like in rheumatic heart disease, leading to post inflammatory scarring, and increasing the pressure gradient over time. Seen in right sided heart failure. There’s more pressure when it’s backflowing to the right side of the heart, leading to pulmonary hypertension because blood is pooling in the lungs (making it not equal), and hypertrophy in the atrial chamber. That side has to pump harder to push it through the lungs, creating higher pressure. Stroke volume decreases.

Mitral Regurgitation: Systolic. High-pitched murmur up to the left axilla. The backflow of blood from the left ventricle to the atrium in systole or from the aorta to the ventricles. The left ventricle needs to pump more volume to compensate for the regurgitant flow and maintain stroke volume. The left atrum and ventricle have hypertrophy to compensate, which maintains for many years prior to symptoms. Sounds like a “whooshing” sound at PMI. Seen in left sided heart failure. Similar to symptoms of stenosis. Weakness and fatigue common.

Mitral Prolapse: Systolic. Myxomatous degeneration (weak connective tissue accumulates gel-like substance, like in EDS and Marfan). The mitral valves will balloon into the left atrium during systole. Women effective twice as often.

What are some disorders of the aortic valves?

The aortic valve is the semilunar valve. Open during aortic systole, and closed during ventricular diastole.

Aortic Stenosis: Systolic. Harsh, mid-systolic at the second intercostal space. You’re getting less blood into the aorta. Sounds like a “whooshing” sound closer to neck. Happens because of calcification of the aortic cusps, or from bicuspid aortic valves congenitally. Age-related, takes a long time to accumulate. Angina common with this, and syncope may occur when cerebral perfusion is inadequate. Surgery is the only treatment.

Aortic Regurgitation: Diastolic. Faint, blowing sound of the aortic apex. The aortic valve allows the blood to leak back into the left ventricle during diastole. Causes are similar to mitral regurgitation. The left ventricle becomes overloaded causing hypertrophy and dilation. May be due to aging.

What are some diseases of the endocardium?

Rheumatic Heart Disease: Happens after rheumatic fever (rare), leading to autoimmune-inflammation attack to own tissues from streptococcal bacteria. Associated with stenosis of the aorta.

Infective Endocarditis: Invasion and colonization of endocardial structures by microorganisms with resulting inflammation. You have to have messed up valves. This leads to fibrin deposits because of the growth of microorganisms. Treatment includes antibiotics for each.

What is myocarditis?

“-myo” means muscle. Myocarditis is inflammation of the muscle layer of the heart, called the myocardium, characterized by necrosis and degeneration of heart muscle cells. The most common cause is post-viral. In some cases, it’s an immune reaction against the myocardium.

What are the types of cardiomyopathy?

Cardiomyopathy is also a type of myocardial disorder. The muscles try to compensate to myocardial damage, so they stiffen over time. Primary is unknown or idiopathic, and secondary is due to hypertension and ischemia.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Most common. Cardiac failure from dilation of one or more ventricular chambers. Caused from alcohol, toxins, viral, genetic, immune, post-viral myocarditis, and idiopathic (everything). More common with left heart failure.

Hypertrophic: The ventricular muscle mass thickens and enlarges. Left and right ventricles thicken, and often asymmetrically; left is more common than the right. May be asymptomatic or associated with ventricular outflow obstruction. Can cause sudden death. Generally genetic, and walls are overdeveloped, leading to less stroke volume. In volume-overload, There’s too much volume in the ventricles. The aorta is narrowed, increasing pressures. In pressure-overload, This causes the walls to thicken to compensate, often from hypertension or aortic stenosis. More common with left heart failure.

Restrictive: Stiff and fibrotic ventricles with impaired diastolic filling. Caused too much iron, sarcoidosis, glycogen diseases, radiation. Results in low stroke volume and heart failure. More common with right heart failure.

How do hearts use electrical activity to beat?

Electrical activity starts at the SA node, then the AV node, bundle of his, splits into left and right branches, and then the purjinke fibers. Action potentials are generated and transported through this system. If small segments are acting independently, it is called fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation can cause clotting, which can increase risk of stroke and heart attack.

Changes in conduction are done based off of EKG. This will tell you if you have ischemic tissue of the heart. It tells you the electrical information of the heart from right to left, superior to inferior, and anterior to posterior. It demonstrates how the electrical activity travels down the heart.

P-Wave: Atrial Depolarization; when the atrium contracts from the SA node.

PR Interval: Atrial/AV/Purjinke Depolarization. This give the atrium time to dump blood into the ventricles, which is the delay in the AV node. This can be used to determine if someone has a heart block.

Q Wave: Septal Depolarization; the initial contraction phase of the ventricle, where it starts. Disruptions in Q waves indicate MI because dead tissue lacks conductivity. This is the beginning of systole.

R Wave: Apical Depolarization; The large contraction of the ventricles. This is so high because the ventricular walls are very thick, especially in the left side.

S Wave: Lateral Wall/ Base Depolarization; affects the purjinke fibers, the finals stage of ventricular systole. This mostly affects the right side of the heart.

T Wave: Ventricular Depolarization; the beginning of repolarization at the J point, or the relaxation of the ventricles. The ST segment represents the resting of the heart cells after the big contraction. The flat line after this segment indicates that repolarization is complete, indicating the start of diastole.

How does blood flow to the heart?

Happens during diastole mostly. Coronary arteries supply the blood because the heart has high oxygen demands. If the demand increases, arteries dilate to increase oxygenated blood. If demands exceeds supply, ischemia develops (like during exercise, stress, big meals, fever).

What is acute coronary syndrome?

Unstable plaque rupture, being the precursor to unstable angina and myocardial infarction. Happens when there is a suspicion or confirmation of myocardial ischemia. Any sudden obstruction causes ischemia (can cause MI or sudden death). The plaque from this can cause an unstable and life threatening atherothrombotic lesion through rupture, erosion, ulceration, fissuring, or hemorrhage. Happens from smoking, sedentary lifestyle, diabetes, high LDL, age can contribute to it (atherosclerosis).

Symptoms: Sudden heavy chest pain that radiates to the neck, back, shoulder, or left arm (heart is on the left side); N&V, dyspnea, and diaphoresis. In women, it can appear like indigestion, fatigue, dyspnea, and anxiety.

Diagnosis: This starts off as being asymptomatic, which is why the EKG looks normal at first, and cardiac enzymes look normal until after the fact.

Treatment: Antithrombotic medications, angioplasty (balloon or stent to push plaque aside).

What is the pathology of acute coronary syndrome?

Plaque can be unstable.

The catting cascade is triggered.

Clot forms at site.

Obstruction happens from clot.

Clot busters, platelet inhibitors, angioplasty is done to stop.

What is angina pectoris?

Recurrent attacks of chest discomfort and pain caused by transient (15 sec to 15 min) myocardial ischemia that is insufficient to produce myocyte necrosis. Often triggered from increased myocardial oxygen demand. Both types have sclerosis. This condition can lead to acute coronary syndrome, which can lead to MI.

Risk Factors: Modifiable types are smoking, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, lack of exercise, obesity, and stress. Non-modifiable types are old age, men, ethnicity, and hereditary causes.

Referred Pain is pain that comes from the jaw, neck, and arm, more often in the left side, that feels like burning, crushing, squeezing, or choking. “Elephant sitting on chest.” May be attributed to indigestion or dental pain.

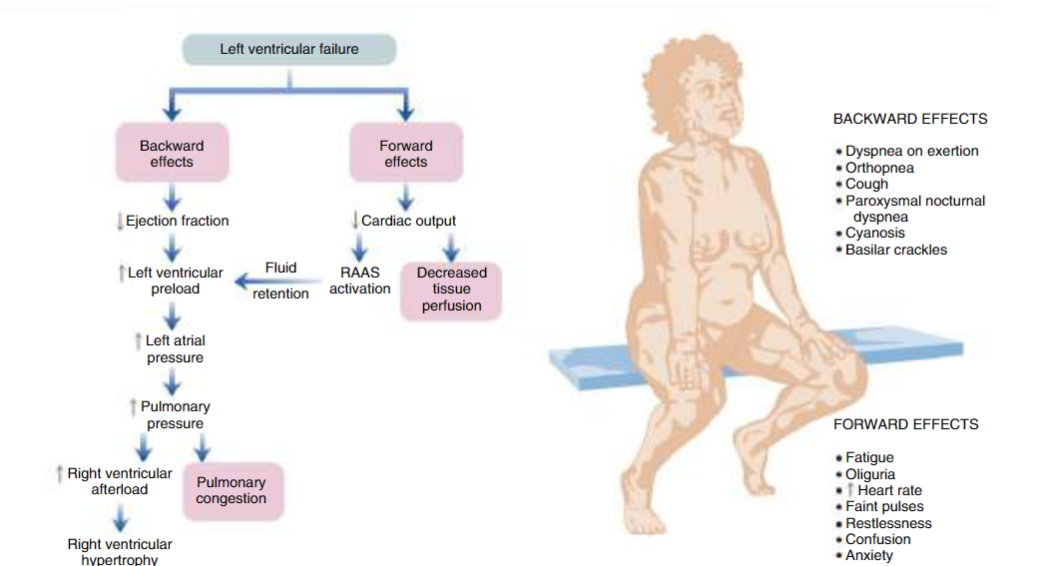

Effects of Left-Sided Heart Failure

Effects of Right-Sided Heart Failure

What are the different types of angina pectoris?

Stable Angina: This is the most common, which is caused from chronic atherosclerosis, leading to less perfusion tan demand. The discomfort is short, 3-5 minutes, does not happen at rest, predictable, and induced by certain activities that increased stress.

Treatment: They can take nitroglycerin or calcium channel blockers (more delayed) to increase perfusion, or may do more rest to prevent stress. Nitroglycerin reduces preload, increases vasodilation, and reduces myocardial workload.

Unstable Angina: Called crescendo angina because they get worse progressively. Associated with plaque disruption and thrombosis; the plaque rips off and ruptures (unstable plaque). Leads to embolization of the thrombus and vasospasm. Will occur over 20 minutes, and can be severe and long-lasting. It can happen at lower levels of activity or at rest, and is not predictable. These can predict MI, because if the clot isn’t dissolved by heparin it can lead to necrosis.

Treatment: PCI (if you do not treat clot quick enough).

Prinzmetal Angina: Uncommon form of myocardial ischemia from sudden coronary artery spasms; not well understood. They can also have atherosclerosis, but they are unrelated to physical activity/heart rate/ blood pressure, and can occur at rest.

Treatment: Vasodilators.

What is acute myocardial infarction?

This is the death of the heart muscle due to prolonged occlusion and ischemia, either through necrosis or apoptosis. Plaque can rupture, triggering the coagulation cascade and fully occluding the arteries. There are several zones of the heart related to cell death. Early manifestations are reversible, but timeframe is very short. After 20-30 minutes, damage is irreversible (blood flow of 10% less of normal). In 90% of cases, we see coronary artery occlusion, which often happens from ruptured atherosclerotic plaques (which is why lipid control is important). In 10% of cases, vasospasms, emboli, dissection, hypertrophy, and dissection happen. If cardiac biomarkers are higher, a diagnosis of MI is appropriate, but if not, then unstable angina is appropriate. May also be diagnosed through EKG.

May appear as ventricular fibrillation. PCI’s may be done 24/7 because of this. Treated with antithrombotics if not fully occluded.

What is coronary heart disease?

Most often caused from atherosclerosis, the narrowing of the arteries. Can also add to thrombus formation, coronary vasospasm, and endothelial cell dysfunction. Less common causes are from abnormal blood oxygen and perfusion. Major risk factors are: age, family, abnormal lipid levels (High LDL, low HDL), genetic hyperlipidemia, cigarettes, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.

Cardiac ischemia happens when the heart’s demand for oxygenated blood exceeds its supply, mostly from impaired blood flow. Th heart requires oxygen to make ATP due to high energy demands, so without it, the heart undergoes ischemia.

Symptoms: Angina pectoris (stable/vasospastic; crushing and squeezing pain down left arm or jaw called referred pain).

After time, unstable plaque can rupture and result in acute myocardial infarction, leading to thrombus formation and total occlusion after the coagulation cascade is triggered . This is potentially reversible (only 20-30+ minutes damage is irreversible).

Sudden cardiac arrest and chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy occurs.

What is the difference between stable/unstable angina, and NSTEMI and STEMI?

Each start from some sort of occlusion that can lead to infarction.

Stable Angina has pain during exercise, and EKG is normal.

Unstable Angina has pain at rest, and EKG is normal. Troponin is normal, but unstable, and often happens before MI.

NTEMI is due to a blockage that leads to necrosis, but limited to the inner layer of the ventricular wall. Troponin is raised. T wave inversion or depression may occur.

STEMI is due to a blockage that leads to necrosis, but blocks the entire ventricular wall. Troponin is raised. ST is very elevated on an EKG.

Troponin is used to determine if there is damage in the tissue to differentiate MI and angina, and become elevated due to . Treatment differs based on EKG reading.

What is heart failure?

The heart isn’t pumping as much as it should, leading to insufficient CO (SV+HR), resulting in less oxygen throughout the body. CHF is heart failure with fluid overload. Happens due to CHD, HTN, valvular heart disease, and cardiotoxic agents.

Low Ejection Fraction/Systolic Dysfunction: The heart has difficulty contracting, so there is less ejection (SV/EDV; less than 35%). The HFrEF is low. Congestive symptoms increases mortality risk. Less volume is leaving the heart, increasing preload. Post-MI can cause this type of heart failure due to cell death and reducing contractile force and apoptosis. Systole is impaired because of less functioning beta-1 receptor function. Aldosterone from RAAS also has toxic effects on the myocardium, contributing more to less contraction.

Preserved Ejection Fraction/Diastolic Dysfunction: The heart has difficulty relaxing, so there is regular/preserved ejection fraction (SV/EDV; more than 50%). The HFrEF is normal. There’s less calcium ions that impair diastolic relaxation. The ventricles will stretch to accommodate filling. Often caused from CHD and HTN. More common in women, elderly, and no history of MI. Age is the most common cause because the heart fibers are less elastic. There is generally slightly more function to the heart, but the chamber cannot fill effectively.

Normal: 60-80% ejection fraction is normal.

What are the compensatory strategies for heart failure?

Lower volume happens from CHD, HTN, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lower contractibility happens from MI, ischemia, and dilated cardiomyopathy.

Compensatory Mechanisms to increase CO:

With lower cardiac output… Activates RAAS through kidneys to increase HR, contractibility, and fluid retention, leading to increased preload, which increases wall tension to progress myocardial hypertrophy, making the disease worse. It enhances the ability of the myocardium to contract, but this lengthens diastole, making contraction shortened.

With higher cardiac output… Baroreceptors increase SNS activation, leading to increased heart rate, contractibility and vasoconstriction. The baroreceptors detect lower pressure in the aorta and carotid arteries. But, the heart may have reduced responsiveness due to the heart failing. Vasoconstriction leads to increased preload, but this will increase afterload to compensate, which decreases stroke volume. That’s why treatment of high blood pressure is important.

With increased ventricular wall tension… myocytes continue to grow, leading to hypertrophy to increase preload and afterload. this is because diastole is increased from high preload. The pumping force increases through wall thickening, causing muscle fibers to elongate. This helps the heart compensate for loss of tissues with MI as well. Angiotensin II has hypertrophic effects on the heart as well, which are produced locally in the heart as well as the kidneys, which is why ACE inhibitors help prevent hypertrophy.

What are beta-1 receptors?

Cell receptors in the heart and kidneys that increase heart rate, contractibility, and the release of renin, impacting blood pressure. Beta-1 receptors in cardiac muscle respond to catecholamines, increasing heart rate and CO.

Beta blockers are medications that help from this triggering, “-lol.” It allows the beta-1 receptor to be less responsive to sympathetic stimulation. Adrenergic drug therapy is the other treatment.

What are the different sides of heart failure?

Left-sided: The most common cause of heart failure. Pumps blood through the circulatory system. If the right ventricle doesn’t work, it also affects the left side, leading to biventricular heart failure. Left sided heart failure often results in right sided as well. This decreases cardiac output to systemic circulation, affecting the lungs, congestion, S3 and S4. S3 is affected from the rapid filling of the ventricle from increased volume load, but may be normal in some. Elevated LAP comes from excessive blood volume and hypertrophy.

Symptoms: Decreases cardiac output, causing fatigue, restlessness, oliguria, tachycardia, anxiety, confusion, and faint pulses. Increased LVEDV and LVEDP has S3 and S4 gallop. Increased left atrial pressure causes atrial arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation). Increased pressure in pulmonary capillaries causes leaking into pulmonary tissues and results in crackles, dyspnea, cough, orthopnea, hypoxia, and cyanosis.

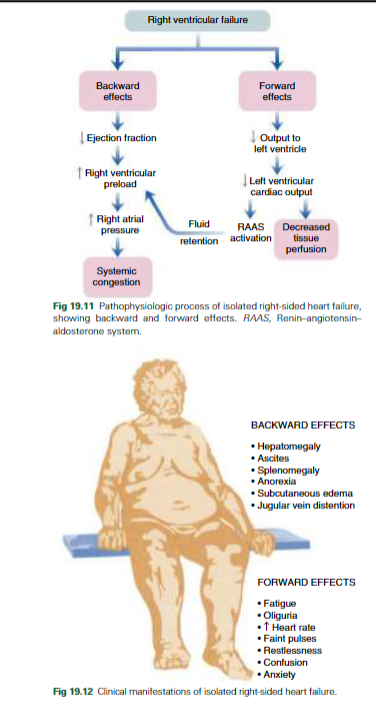

Right-sided: Pumps blood in the pulmonary system, which is why lung disorders contribute to this type because of hypoxemia. Not as common when it’s the right alone, and can lead to right ventricle infarction or pulmonary disease from higher afterload in the right ventricle. Left ventricular failure also results in left ventricular failure eventually. This decreases systemic circulation and affects the body. The causes of right ventricular failure are the same as the left. Causes Cor Pulmonale, which is right ventricular hypertrophy, and may cause right ventricular failure.

Symptoms: Right ventricular pressure leads to sternal heave, RV S3. Right atrial pressure causes JVD. Systemic capillary pressure is leaking into body tissues, leading to peripheral edema, ascites/abdomen fluid accumulation, anorexia, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly.

Forward Effects: Everything that happens after the left ventricle. There’s less preload from left-sided heart failure from the failure of the ventricles, so the volume of blood that goes to the rest of your organs doesn’t happen from decreased perfusion. This causes ischemia, and eventually necrosis.

Symptoms: (Left) Lower cardiac output and inadequate oxygen supply. Vasoconstriction increases afterload, damaging the left ventricle, causing it to have more force to pump.

(Right) Lower cardiac output and inadequate systemic circulation, leading to lower oxygen supply. RAAS is activated to increase fluid retention, and tissue perfusion is decreased. Fatigue, oliguria, increased heart rate, faint pulses, restlessness, confusion, and anxiety present.

Reduced perfusion of the kidney leads to oliguria, restlessness/confusion/anxiety/fatigue from lack of brain perfusion.

Backward Effects: Everything that happens before the left ventricle. The backwards effects of the left ventricle that affects oxygen perfusion from all organs, but primarily the lungs in left-sided heart failure.

Symptoms: (Left) Affects the lungs, causing pulmonary congestion and increased RV afterload, eventually leading to RV failure. Pulmonary circulation decreases as hydrostatic pressure builds up, impacting gas exchange, and leading to pulmonary edema. This causes productive cough, crackles, dyspnea, and breathlessness. Breathing gets more difficult lying down. Cyanosis occurs from difficulty with oxygen perfusion throughout body.

(Right) Affects the body, causing congestion in the abdomen (bloating, anorexia, ascites) and JVD. Congestion occurs, which impacts the function of the liver, spleen, kidneys, subcutaneous tissues, and brain, causing swelling and hypermegaly in these systems. Liver is increased; hepatocytes show necrosis and leads to ascites in the peritoneum. Also leads to decreased GFR, which increases fluid retention in the extremities. JVD occurs from sudden distention.

What are the stages of heart failure? How is it managed?

Diagnosed through FACES: Fatigue, activity limitation, congestion, edema, and shortness of breath; X-ray of the pulmonary system edema; EKG (gold standard); BNP to see the level of damage.

BNP helps to identify this, which is a blood test.

AHA has ABCD: A means at-risk from clinical symptoms, B means they have have Hf structure but no symptoms, C means they have previous symptoms of HF, and D means there is advanced structural failure and symptoms of HF at rest.

Treatment: Daily weights (determine fluid retention and heart failure level), low-sodium diets, diuretics (decrease fluid retention, blood volume), and ACE inhibitors (control blood pressure and decrease afterload by preventing vasoconstriction) for blood pressure, and B-adrenergic agonists for cardiac contractibility.

Long-term use is associated with higher mortality. ARB, aldosterone agonist, B1-blockers, and ACEI’s help reduce mortality risk.

What are the five types of shock? How are they treated?

Shock is treated similarly to heart failure as it attempts to maintain mean-arterial pressure t protect organs. As shock progresses, blood is shunted to brain and heart, AKI, and organ failure happens.

Cardiogenic Shock: Due to decreased cardiac function from MI or cardiomyopathy, resulting in decreased CO from tissue hypoxia. The heart is causing the problem.

Treatment: Inotropic medications, give oxygen to limit infarct size, and intra-aortic balloon into the acute region.

Hypovolemic Shock: Loss of whole blood (hemorrhage, burns, fluid), plasma (burns), or fluid (diarrhea, diaphoresis, emesis, diuresis).

Treatment: Give large amounts of fluid.

Anaphylactic Shock: Hypersensitivity reaction from vasodilation, causing hypovolemia; decreased tissue perfusion and impaired cellular metabolism, depriving organs.

Treatment: EpiPen, catecholamine that increases blood pressure and heart contractibility, dilating the bronchi.

Neurogenic Shock: Widespread and massive vasodilation that results from parasympathetic overstimulation or sympathetic under stimulation.

Treatment: Remove or treat the cause (spinal, SNS depression, anesthetic, pain/stress).

Septic Shock: The most common, a part of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Bacteria enters the blood stream, causing a person to go into sepsis. 40% of cases lead to death from gram negative or positive bacteria (viruses and fungi possible, but rare).

Treatment: Drug antibacterial therapy, remove infection source, fluid resuscitation, and vasodilative medications to improve hemodynamics.

What are the complications of shock?

ARDS happens due to acute lung inflammation and diffuse alveolocapillary injury with pulmonary edema.

DIC happens due to micro blood clots forming causing tissue damage and using clotting factors; clotting and bleeding simultaneously.

Acute Renal Failure, Multi-Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (high mortality).

Symptoms: Dilated pupils, clammy skin, anxiety, altered mental status. Causes metabolic and respiratory acidosis with hypoxemia.

Diagnosis: Vital signs (hypotension, tachycardia, narrow pulse and pressure, tachypnea).

What are the types of brain injury?

Brain injury can be caused from: mechanical trauma, ischemia, cellular energy failure, reperfusion injury, excitotoxins, edema, vascular failure, and injury-induced apoptosis. There are primary types, which occur immediately after injury, which often cannot be reversed. There are also secondary types, which develop further neurological damage and changes subsequent to the primary injury, or longer term cell death through necrosis or apoptosis (can happen over years).

Ischemia: When oxygenated blood is less than the level needed to meet metabolic demands of the brain. Primary examples are stroke secondary examples are vasospasms. Neurons are no longer able to generate ATP needed for energy-processes through lack of oxygen. The brain takes 20% of the body’s oxygen, but has no way of storing it. Glycolysis may be done for short periods, but anaerobic processes cannot be maintained long. Excess calcium builds, glutamate builds to toxic levels (excitotoxin), creating excess NO, resulting in cellular energy failure. Free radicals damage cells, leading to apoptosis and necrosis.

Hypoxia: Deficiency of oxygen at the cellular level, either due to decreased blood flow (ischemia) or decreased blood oxygen (hypoxemia). Often occurs alongside ischemia.

Ischemia and hypoxia can be caused from cellular energy failure, excitatory amino acids (glutamate), reperfusion injury (free radicals react to oxygen and become toxic), and abnormal autoregulation (body doesn’t recognize mismatch of CO2 and O2).

Increased Intracranial Pressure: Normal pressure is 0-15 mmHg in adults. If there is a large imbalance between blood, CSF, and the brain, then no compensation can form from increased pressure (compliance). Temporary changes are safe, but chronic results in symptoms. Vessels can constrict, CSF can drain into the spinal column, and skulls can move outwards in children. Increased ICP is often caused from stroke, trauma, tumors, or other primary and secondary disorders. Happens from brain compression and herniation (from elevated ICP). Interstitial edema, increased capillary pressure, vasogenic edema, cerebral edema, and cytotoxic edema may cause it. Tumors, hematomas, and abscesses as well. Hydrocephalus is the increased in CSF, not allowing for reabsorption. Compression of the midbrain and brainstem is associated with rapid neurologic demise.

Symptoms: Headache, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, and altered level of consciousness. Herniation is the protrusion of brain tissue through an opening in the dura mater of the brain. At worst, can result in coma.

Treatment: CT, surgery, removal of excess CSF, medication. Treatment should maintain ICP to less than 20 mmHg and CPP of 50 mmHg or greater. Continuous EEG may be required.

How are brain injuries measured?

Level of Consciousness: Patient can be confused (unable to think clearly, low A&O), delirious (restless and disoriented, hallucinations), lethargic (uninterested and sluggish), obtunded (falls asleep quickly)posture s stimulation), and comatose (complete inability for arousal).

Glasgow Coma Scale: Measures level of consciousness in acute brain-injured patients. Eye opening (how much stimuli until eyes open 1-4), verbal response (alert and oriented scale, inappropriate behavior 1-5), and motor response (abnormal movement and pain, 1-6).

Decorticate posture flexes inwards, decerebrate posture flexes outwards as a part of the motor portion of the glasgow coma scale.

Pupil Reflexes: Doll’s Eye Maneuver tests to see if you can keep pupils on one area while moving head, and Caloric Reflex Test is done by squeezing cold water into the ear canal to see if eyes will move.

What is a TBI?

TBI is the leading cause of death and disability for young adults, caused from falls, sports, violence, and transportation. They are categorized by severity, location, and mechanism of injury. Focal injuries are on a specific region that are observable, and diffuse injuries creates a shaking effect causing distortions in the brain seen through a microscope. Injuries can also be caused from initial impacts (coup) or rebounded (countercoup) from the movement of the brain in the cavity.

Primary TBI: Intracranial hematomas (epidural, subdural, subarachnoid). Focal injuries stay localized to the site of the impacted tissue, and damage is variable. Diffuse is seen when there’s a rotational injury causing widespread neuronal damage.

Secondary TBI: Secondary mechanisms cause far more damage than the primary trauma. Uncontrolled brain bleeds, increased ICP, fractures, ischemia, and vascular regulation causes further damage to the brain.

Symptoms: Varying levels of consciousness, low Glasgow coma scale (eye, verbal, and motor response levels), and lowered cranial nerve reflexes (pupil, oculovestibular, corneal). Pupils may remain a certain size or can be unequal on each side. There can be abnormal skeletal posture responses (decorticate flexion, decerebrate pronation).

Breathing patterns can be altered, depending on the region of damage. Shown on a graph of inspiration and expiration, with some breaths being rapid and erratic, and other beings prolonged and causing gasping.

Treatment: Surgery, ICP management, medication, CSF drainage, seizure prophylaxis, and antibiotics to prevent infection.

What is the difference between a cerebral aneurysm and arteriovenous malformations?

Cerebral Aneurysms: Aneurysms occur in 30,000 people per year in the US. They happen because of congenital weakness in the arterial walls, leading to dilation and ballooning that causes sentinel (warning) leaks in the brain. May be considered asymptomatic prior rupture, but severe headaches may also onset. These are considered a neurosurgical emergency if ruptured and will need to be sent to CCU. Vasospasm is the most common complication. Happens pretty deep in the brain.

Treatment: Dependent on aneurysm location, shape, and neck size. CT with contrast is performed to see location. Craniotomy and cutting the aneurysm may be necessary.

Arteriovenous Malformations: Second most common cause of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage, and more common in men (not familial). Congenital, but rarely diagnosed in children. The arterial blood is shunted directly into the venous system without a capillary bed, causing high venous pressure, enlarged AVM, and causes nearby structures to be compressed or rupture. These abnormal structures and high pressure are vulnerable to hemorrhage.

Treatment: Surgical management, radiation, or endovascular embolization to occlude the AVM to prevent bleeding.

What are the classifications of brain bleeds?

Brain bleeds happen because of an injury. The brain is not attached to the skull directly, meaning that sudden changes in motion can tear blood vessels. Bleeds shift and distort the brain, herniate brain tissue (push it out of place), or compress blood vessels (ischemia). This can happen because of an aneurysm or arterial bursting from later stage chronic hypertension.

Hemorrhagic Stroke: Within the brain, most often from arterial aneurysms bursting.

Epidural: Between the skull and dura, often from arterial causes. In the epidural space. There are many vessels in this space, making them vulnerable. Usually arterial.

Subdural: Between the dura and arachnoid, often from venous causes. Harms bridging veins, by stretching them apart, which bring venous blood from the surface of the brain to the middle before emptying in the venous sinuses. Slower bleed from less pressure. Acute or chronic. Usually venous.

Subarachnoid and Intracerebral: Between the pia mater and the brain (into the CSF) or brain tissue. This can be venous or arterial.

Symptoms: Severe headache, change in consciousness, glasgow coma scale, and brain stem function (pupillary response, corneal reflex).

What is a cerebrovascular accident, or stroke?

This is the most common cause of disability in the elderly, and the fifth leading cause of death in the US. 1/3 of people either: die, experience chronic deficit, or have functional recovery. 20% are hemorrhagic with a ½ chance of mortality, and occur in the intercranial or subarachnoid space due to vessel bursting. These are sudden and serious, and often result from untreated hypertension. 80% are ischemic (embolic from A. Fib or high lipids, thrombotic), and occur from the block of blood flow, or occlusion, of cerebral arteries secondary to thrombus formation. Emboli are often cardiac, related to atrial fibrillation. Ischemic strokes must re-perfuse within 3 hours of onset.

Transient Ischemic Attack: An episode of stroke symptoms that last less than 24 hours (usually 20 minutes), and are less severe.

Right Stroke: Affects spatial abilities, judgement (no awareness), memory (short-term), and mood (indifference, impulsive).

Left Stroke: Altered speech (aphasia, cannot communicate), slow and cautious step-by-step behavior, difficulty learning, and depression.

Risk Factors: Hypertension, A. Fib, Black people, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, atherosclerosis, sedentary, and prior TIA. Can be prevented with platelet or anticoagulants.

Symptoms: Numbness or weakness on one side (spasticity), confusion, difficulty with speech (aphasia), visual disturbances, dizziness, trouble walking, and severe headache (hemorrhagic stroke).

Treatment: Minimize infarct size, STAT CT with contrast, aspirin, thrombolytic therapy, mechanical thrombectomy, anticoagulants, blood pressure management. Surgery may be required in hemorrhagic stroke.

How does lack of blood flow affect our cerebral functions?

Basilar: Feeds the cerebellum and brain stem. Lack of flow affects gait, speech, swallowing, and vision.

Anterior Cerebral: Feeds the frontal lobes. Lack of flow affects motor sensory loss, impaired cognition, incontinence, and aphasia (in left side strokes).

Middle Cerebral: Middle of brain. Lack of flow causes contralateral motor and sensory loss, aphasia, altered consciousness, and neglect syndrome. Lack of flow to this area is the most fatal.

Posterior Cerebral: Occipital and temporal. Lack of flow causes vision and memory loss.

What are the types of central nervous system infections?

Meningitis: Inflammation of the meninges. Most common cause is due to microbial invasion of the CNS. It’s most often bacterial, but can be viral or fungal. Common in those with compromised immune systems. Most often caused from streptococcus pneumoniae, and travels throughout the subarachnoid space. Causes fever, headache, neck stiffness, or LOC alterations. Treatment is supportive care, IV antibacterial therapy (after cultures), corticosteroids, and management of complications.

Encephalitis: Inflammation of the brain parenchyma, which is the functional tissue of the brain that contains neurons. Can be caused from viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites. Can be caused from herpes simplex virus, often from type 1. Results in hallucinations, personality changes, seizure, confusion, and coma. Gram stain and cultures should be assessed through lumbar punctures. Treatment is supportive and symptomatic; fluid resuscitation, treatment of pain, and management of seizures. MRI preferred over CT. Surgery may be required, and this is considered a medical emergency.

Brain Abscess: Pus in the the brain parenchyma. Pathogens reach the brain and infect this space through wounds, infected neighboring structures, or travels from distant infected sites. Most are bacterial. Streptococci are the most common. Headache begins 1-4 weeks after initial infection. Inflammation and edema persist. Treatment is drainage/excision for larger lesions and long-term antibiotics for smaller ones. Antibiotics can rarely treat larger abscess.

What is epilepsy?

Neurological events caused from neuronal electrical discharges that disturb motor function, sensation, behavior, and consciousness. The plasma membrane is more permeable, which makes the membrane potential neurons more sensitive to paroxysmal depolarization (like glutamate) causing a rapid influx of Na+ and outflow of K+. Length of time during episodes are variable. Can be caused from: genetics, perinatal injury, metabolic abnormalities, B6 deficiency, brain injury, infection, and toxins. May be encouraged by free radicals and oxidative stress. The threshold for seizures may be lower in others, and can be caused by: hyperthermia, hypoxia, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, repeated sensory information, stress, fatigue, and lack of sleep.

Symptoms: Seizures, which are sudden, explosive, disorderly charge of brain neurons. They produce a brief disruption of electrical function, affecting consciousness and motor, sensory, autonomic, or psychic systems. They may result in convulsions (tonic-clonic) that can cause cyanosis and respiratory distress, along with increased pulse and loss of bodily function. Seizures may be idiopathic with no defined origin. There are different types: focal onset, general onset, and unknown onset. Status epilepticus occurs when seizures are life-threatening and constant, with little reprieve among seizure episodes.

What are the different types of dementia?

Dementia, in general, is due to the progressive deterioration and decline of memory and cognitive changes. It is a syndrome and not a disease. They can either be neurodegenerative, or non-neurodegenerative. divided into early, middle, and late stages depending on severity of symptoms. Symptoms can initially appear like normal signs of aging, or depression. Risk is associated with family history (autosomal dominant), physical health, mental health, and age.

Alzheimer’s Disease: 60-80% of all dementia due to the degeneration of neurons in the temporal and frontal lobes, leading to atrophy of the brain. Beta-amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are evident, alongside neuronal degeneration. They become embedded in the cell membrane, where the beta protein becomes cleaved and allows the formation of plaque. NFT’s alters the protective structure of these helicase molecules, resulting in neuron death. These begin years before onset of symptoms. Inflammation can also contribute to development through activation of cytokines. These create degeneration in nerve cell communication, metabolism, and repair.

Symptoms: Begins slowly and may be confused with age-related memory changes, with trouble recalling recent events, activities, or names of familiar people or things. Middle and late stages have symptoms that are more easily noticed and affects ADL’s. In middle stages, simple tasks are difficult and thoughts are no longer clear; cannot recognize tings that should be obvious. They have difficulty with speaking, understanding, reading, and writing. In later stages, they can become anxious, aggressive, wander, and need total care. Patients often have agnosia, or they lack insight towards their cognitive deficiencies. Symptoms are associated with imbalances of glutamate, dopamine, and serotonin.

Delirium is common, alongside disturbed sleep-wake cycles, decreased awareness of environment, drowsiness, restlessness, incoherence, hallucinations, and difficulty maintaining attention.

Treatment: No treatment can stop it, but medication help slow the progression. Medications can target restlessness, agitation, wandering, anxiety, and depression. But, side effects can worsen disease, so behavioral interventions are far more effective by making patients more comfortable.

Vascular Dementia: Second most common form of dementia due to a single cerebrovascular insult, multiple lacunar infarcts, or microvascular pathology. Symptoms are similar to Alzheimer dementia. Both trigger innate immune responses, and there may be more of a correlation between the two as opposed to them being two separate conditions. Treated using AChEIs and NMDA, and medications that control blood pressure, blood sugar, and lipids.

Symptoms: Lower attention, memory, executive functioning, language, spatial orientation, and judgement. Assistance with ADL’s will become gradually more necessary.

What is the difference between delirium and dementia?

Delirium: Abrupt onset, physiologic cause, reversible, fluctuating, and altered levels of consciousness.

Dementia: Progressive failure, irreversible, confused, and declined abilities.

What is parkinson’s disease?

A motor system disorder due to the loss of dopamine-producing brain cells. These produce Lewy bodies, making it associated with dementia due to plaque buildup in the brain, and from neuroinflammation. Usually affects people over the age of 50. In some, the disease progresses quicker than others. There are no blood or laboratory tests to diagnose it. Can be idiopathic or acquired (infection, intoxication, trauma).

Symptoms: Early signs are minimal blinking and loss of facial expression. Tremors (trembling in hands, arms, legs, jaw, and face), rigidity (stiffness), bradykinesia (slowness of movement), and postural instability (impaired balance and coordination). As symptoms worsen, patients may have difficulty walking, talking, or completing tasks. Also causes depression, difficulty swallowing/chewing/speaking, urinary problems and constipation, skin problems, and sleep disruptions. Symptoms present unilaterally but become bilateral with progression.

Treatment: No cure, but some medications can provide relief (carbidopa-levodopa). Other drugs mimic dopamine in the brain. Surgery if no response to medication. Deep brain stimulation through electrodes connected to a pulse generator can provide relief. Pallidotomy can be done due to overactive globus pallidus; scars are created in this region to reduce brain activity and help relieve movement symptoms.

What happens during spinal cord injuries?

Forced trauma from compressed tissues, pulling or exerting on tissues, or shear tissues affecting the spinal cord can cause this. Bones, ligaments, and joints of vertebral column may be damaged due to fracture, dislocation, or both. There’s damage to motor neurons. Herniated intervertebral discs or bone spurs can cause it as well; trauma or compression (tumor, hematoma). And results in partial or complete severing of the spinal cord due to cord ischemia, so never move someone suspected with this without stabilizing them. More common in younger people.

Symptoms: Loss of voluntary control, flaccid paralysis, decreased muscle tone, atrophy, hypertension, and decreased or absent reflexes. Can have spinal shock with widespread dysfunction. Neurogenic shock possible.

Location: Long term loss depends on level of injury and extent of transection. C2 is ventilator dependent and quadriplegic. C4 can move head, shoulders, and diaphragm. C6 can have weak hands. T1 has normal upper body, but paraplegic.

What is multiple sclerosis?

Autoimmune degeneration of previously normal myelin with relative preservation of axons. May occur when a previous viral insult to the nervous system has occurred in genetically susceptible individuals. Can occur anywhere in the CNS. CD4 T-cells cross the BBB, followed by chemotaxis and infiltration of monocytes and macrophages. T-cells become autoreactive to a single myelin protein. Onset is between 20-40, with a male to female ratio of 1:2. White matter lesions and plaques in MRI.

Symptoms: Stress is often the trigger of the onset of symptoms, but symptoms vary in severity and presentation. Causes paresthesias (numbness, tingling), weakness, tightness, banding, itching, constriction, imbalance/ataxia/lack of coordination, visual changes (blurring, double-vision). Bowel and bladder difficulties, vertigo, pain, and paresthesia may also be present.

What is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis?

Also called Lou Gehrig’s disease. Most common motor neuron disease in the US, affecting lower and upper motor neurons. 90-95% of cases are random, but 5-10% are familial. Diagnosed from 40-60, but higher in men in earlier stages. After menopause, likelihood is equal for men and women. It’s neurologically degenerative (but no sensory or cognitive changes), rapidly progressing, and fatal. Associated with genetics and gender, but also agriculture, military, manual labor, muscle use.

Symptoms: Weakness and wasting of muscles, muscle atrophy from motor neuron degeneration, sclerosis from lateral column of spinal cord, Amyotrophy is without muscle nutrition or progressive muscle wasting. Difficulty swallowing, secretions, communication, and respiration. Hands and upper extremities are often affected first.

Diagnosis: In early stages, motor neurons spout new branches to reinnervate muscle fibers, causing weakness but progressing to flaccid or spastic paralysis. After ½ of motor neurons gone, reinnervation fails, causing weakness. Death happens within 2-5 years of onset of symptoms, often from respiratory failure.

What is Guillain-Barre syndrome?

A heterogenous autoimmune syndrome with multiple variants: AIDP, AMAN, AMSAN, and MFS. Peak disability is within 3-4 weeks. The most common cause of nontraumatic paralysis. Caused after bad bacterial infection. Post-infectious immunologic mechanism such as cross-reactive antibodies to peripheral nerves is suspected. Affects primarily motor neurons, causing paralysis on both sides, but can affect sensory neurons as well. Treatment is supportive. Can have spontaneous recovery, with gradual improvement over time.

Symptoms: Muscle weakness in lower extremities that spreads to proximal spinal neurons. Paresthesia or dysesthesia, neuropathic pain, loss of autonomic regulation.

What is Bell’s Palsy?

Rapidly developing paralysis of the muscles on one side of the face (over 24-48 hours), often from a self-limiting condition with unknown cause. Often caused from infection, sarcoidosis, tumor, stroke, but in half of the cases, it’s idiopathic. Hyperthyroidism, diabetes, and pregnancy are risk factors. Treatment is supportive. Can have spontaneous recovery; may only last a few days or weeks.

Symptoms: Unilateral facial weakness with facial droop, diminished eye blink, hyperacusis, decreased lacrimation, loss of taste, and pain may be present. 30% of patients are left with some level of disability.

How is glucose controlled in the body?

Glucose homeostasis is controlled by: glucose production in the liver, uptake and utilization by tissues (skeletal muscle), and actions of insulin and counter-hormones like glucagon. Insulin and glucagon have opposing effects on maintaining glucose homeostasis.

The ability to regulate protein and fat metabolism is determined by the anabolic effects of insulin. Insulin is created from beta cells in the pancreas, while glucagon is created from alpha cells. When glucose interacts with a beta cell, it goes through a series of steps to create insulin. Insulin also maintains skeletal muscle, preventing breakdown by increasing or decreasing the release of amino acids by skeletal muscle. Normal glucose metabolism is described in reference to the fed (absorptive) and fasting states (low insulin and high glucagon). Glucagon dominates the fasting state, which is responsible for 75% of glucose production in fasting states. Hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis (glucagon-led) leads to neural influences from the SNS and PNS are directly involved with carbohydrate metabolism and glucose utilization. Glucose is produced by glyconeogenesis (broken down stored glycogen), and in the liver and muscles by gluconeogenesis (creation of glucose from amino acids/other). In the fasting state, the primary source of energy for muscles is free fatty acids from lipolysis during the breakdown of adipose tissue.

Glucose is maintained through exercise. Increasing activity requires fuel for muscle tissue. Skeletal muscle is the major responsive site for postprandial glucose utilization, which is critical for preventing hyperglycemia and maintaining glucose homeostasis. The decrease in insulin and the increase of glucagon and catecholamines lads to elevated blood glucose levels. Exercising muscle increases insulin sensitivity, which facilitates glucose uptake.

During stress, hormones increase blood glucose level and oppose the effects of insulin. Catecholamines, glucocorticoids, and glucagon may precipitate stress hyperglycemia. Corticosteroids stimulate gluconeogenesis and counteract the hypoglycemic action of insulin. Growth hormone increases peripheral insulin resistance. Catecholamines augment glucose production by prompting glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis (increase plasma glucagon levels), and catecholamines influence muscle tissue to use fatty acids for fuel as opposed to stored glycogen.

How is insulin regulated in the body?

Glucose is the most important stimulus for insulin release and synthesis. This process is stimulated by the parasympathetic nervous system, stimulating beta cells for insulin release. Glucose stimulation releases insulin, which creates persistent stimulation signals for insulin synthesis (which is the first phase of release). Oral food intake leads to secretion of multiple hormones that paly a role in glucose homeostasis and satiety. Incretins, the precursor to insulin, bind to G-protein coupled receptors that are expressed on pancreatic beta cells and promote insulin secretion.

GIP and glucagon-like peptide-1 are secreted by cells in the intestines, and represent the incretin effect: This leads to increased insulin secretion from beta cells, reduced glucagon from pancreatic alpha cells, and delayed gastric emptying, increasing satiety. Amylin is a peptide hormone that is produced by pancreatic B cells and consecrated with insulin, which helps with satiety and to prevent postprandial blood glucose spikes. Circulating GIP and GLP-1 is degraded by DPP’s in circulation. Incretin is blunted in people with T2D (which is why weight loss is effective in restoring satiety).

What are the causes of diabetes? What is prediabetes?

Diabetes is common, affecting 11% of the US population. 22% are undiagnosed. To be diagnosed, you must have a fasting plasma glucose of 126, a random glucose of over 200, a 2-hour test of OGTT with glucose over 200 (75g drink), and an HbA1c of over 6.5 % (normal range is 70-120, 100-120 is pre-diabetes when fasting). However, transient hyperglycemia can be caused from acute stresses. Diabetes can also result from genetic defects of beta cell function, genetic defects in insulin action, exocrine pancreas defects, infections, dugs, and genetic syndromes associated with diabetes (down syndrome, klinefelter, turner, prader-willi).

Prediabetes: Impaired glucose tolerance and fasting glucose levels, which is in-between normal glucose levels and the onset of diabetes. 25% of people with this will develop overt diabetes within 5 years (family history, obesity). Risk for cardiovascular complications.

Diagnosis: A fasting glucose of 100-125, a 2-hour glucose of 140-199 following a 75g OGTT, and an A1C of 5.7-6.4%.

What is type 1 diabetes?

Type 1 Diabetes: The autoimmune destruction of beta cells in the pancreas, leading to the absolute deficiency of insulin. Macrophages and T lymphocytes produce autoantibodies against various types of beta cells, which secrete cytokines and direct cytotoxic action. Antibodies can secrete up to 13 years prior to diagnosis. Glucose cannot enter muscle and adipose tissue from insulin deficiency, and production of glucose by the liver is no longer opposed by insulin. There is also overproduction of glucagon by pancreatic alpha cells. so insulin is needed for survival to prevent ketoacidosis. Can happen at any age, but more often happens at 2, 4-6, and 10-14. Idiopathic is rare. It’s autoantibody-negative; major linkage to MHC class II genes because they help with the creation of surface proteins. Viruses can trigger the autoimmune process in susceptible individuals.

Symptoms: Glucose is lost in urine, leading to hypovolemia. Neural tissue responds to this through polydipsia, polyuria, and polyphagia, causing the classical diabetes symptoms. Normal weight or weight loss, progressive decrease in insulin, circulating islet autoantibodies, diabetic ketoacidosis without insulin therapy. Causes insulitis (inflammatory T cells and macrophages) and beta-cell depletion, islet atrophy.

Diagnosis: Genome studies determine the locus in the HLA gene cluster, which contributes to 50% of cases of type 1 diabetes. Check history of viruses, which may be a trigger (molecular mimicry).

Stages: Stage 1 is autoimmune positive, normal blood sugar, and pre-symptomatic (development of 2+ islet autoantibodies). Stage 2 is autoimmune positive, abnormal blood sugar, and pre-symptomatic (severe loss of glucose tolerance due to loss of beta cell mass). Stage 3 is autoimmune positive, abnormal blood sugar, and symptomatic with presentations of polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, and ketoacidosis (90% of beta cells have been destroyed).

Treatment: 2-4 insulin injections per-day. Types of insulin vary in onset, intensity, and duration, which can be quick, intermediate, and long-acting. Fever, stress, infection, pregnancy, surgery, and hyperthyroidism increase insulin requirements. Liver disease, hypothyroidism, vomiting, and renal disease decrease insulin requirements.

What is type 2 diabetes?

Type 2 Diabetes: The resistance to insulin on peripheral tissues and the secretory response of pancreatic beta cells that are inadequate to overcome insulin resistance, leading to dysfunction (relative insulin deficiency). Insulin resistance happens before the development and usually starts with beta cell hyperfunction to compensate with hyperinsulinemia in the early stages, overall leading to their dysfunction. Hyperglycemia can lead to further insulin resistance, making insulin secretion worse over time. Genetic and environmental factors create a pro-inflammatory state, not an autoimmune condition. More and more common because of sedentary lifestyle and poor diet, higher rates of obesity (most important risk factor), so often considered adult-onset (more common as you get older). No HLA linkage.

Symptoms: Nonketotic hyperosmolar coma more common. Amyloid deposition in islets with mild beta cell depletion. Chronic hyperglycemia from inability of beta cells to react.

Treatment: Non-pharmacologic interventions are: weight loss in type 2 (even just 10 pounds), exercise, and diet (low glycemic foods). Pharmacological treatments are: oral compounds (to increase insulin secretion and sensitivity in muscle), and insulin (when glucose is poorly controlled, may be necessary with islet cell depletion). Type 2 is progressive, so insulin may be necessary over time, especially with stress. GLP-1 receptor agonists are newer therapies that increase energy expenditure and weight loss. DPP-4 inhibitors enhance levels of endogenous incretins by delaying their degradation. Sulfonylurea drugs are the common treatment, which bind to ATP potassium channels on the cell membrane of beta cells, increasing intracellular calcium concentration. Metformin, a biguanide depresses hepatic gluconeogenesis, which enhances glucose uptake by peripheral tissues without causing hypoglycemia.

What is gestational diabetes?

Gestational Diabetes: Pregestational and gestational diabetes levels is increasing, with 5-9% of all pregnant people having complications. Gestational diabetes happens when someone with pre-existing diabetes becomes pregnant (pregestational), or a person with normal blood glucose becomes pregnant and gets diabetes for the first time (gestational). Looks similar to type 2 diabetes. Develop insulin resistance, and may be genetic and environmental in influence. Pregestational diabetes increases risk of stillbirth, excess birth weight (macrosomia), long-term sequelae, and congenital malformations. Symptoms resolve upon delivery, but most people will develop overt diabetes within 10-20 years.

What is insulin resistance?

The liver undergoes gluconeogenesis, or the creation of glucose from non-carbohydrate sources, but the liver fails to be able to do this, leading to high fasting blood glucose. The failure of glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis in the skeletal muscle leads to high postprandial blood glucose level. Failure to inhibit the activation of hormone-sensitive lipases in adipose tissue leads to excess triglyceride breakdown in adipocytes and high levels of free circulating fatty acids.

What are the complications and manifestations of diabetes?

Diabetes can cause widespread organ damage leading to end-stage renal disease, adult-onset blindness, and non-traumatic lower extremity amputations. Diabetes usually causes polyuria, polydipsia, and polyphagia from metabolic derangements.

Acute Hyperglycemia: Commonly caused by alterations in nutrition, inactivity, inadequate use of medication, or a combination. Fasting blood glucose may be higher in the morning, leading to the dawn phenomenon. Polydipsia, polyphagia, and polyuria are the short term acute complications of diabetes. Nausea, fatigue, and decreased sense of wellbeing frequently accompany hypoglycemia.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis: Occurs primarily in type I diabetes as a result of increased lipolysis and conversion to ketone bodies, which results in metabolic acidosis. Most often caused when patients do not take their insulin, but can also be caused by stressors. Stress increases epinephrine, which blocks insulin action and stimulates the secretion of glucagon. The mixture of insulin deficiency and glucagon excess leads to decreased utilization of glucose while increasing gluconeogenesis, leading to severe hyperglycemia (250-600 mg/dL). Lipids broken down from lipolysis create ketoacids in the liver, resulting in low blood pH and increasing osmotic fluid loss. Hyperglycemia leads to osmotic diuresis and dehydration. And, without insulin, there is too much potassium in the vascular space because the sodium-potassium pump requires insulin to work, leading to hyperkalemia. Can result in fruity breath from compensatory respiratory alkalosis. Most critically important to check potassium levels.

Occurs less commonly in type 2 diabetes from extreme trauma.

Nonketotic Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Syndrome: More common in type 2 diabetes because endogenous insulin suppresses ketone formation and thus prevents ketoacidosis. Portal vein insulin levels prevents unrestricted hepatic fatty acid oxidation and keeps the formation of ketone bodies balanced. Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic states cause severe dehydration from sustained osmotic diuresis, particularly in those who are unable to maintain adequate water intake. Because there is no ketoacidosis (nausea, vomiting, kussmaul breathing), hard to seek medical attention until severe dehydration. Thy hyperglycemia is typically more severe, from 600 to 1200.

Chronic Hyperglycemia: Vascular complications include macro and microvascular problems. Atherosclerosis causes vessel-related damage to the large blood vessels. Capillary membranes will thicken their basement walls because of persistent hyperglycemia. Common symptom is retinopathy because of aneurysms in eye capillaries, leading to blindness. Neuropathic complications include autonomic and sensory dysfunction. GI, bladder disturbances, tachycardia, postural hypotension, and sexual dysfunction. Glycemic control improves nerve function, uncontrolled damages the. Neuropathy can lead to lower amputations.

Hypoglycemia: The most common acute metabolic complication in either type of diabetes is hypoglycemia. Caused from missing meals, too much exercise, excessive insulin. Signs and symptoms include dizziness, confusion, sweating, palpitations, and tachycardia. If persistent, can cause loss of consciousness and seizures. Rapid reversal of hypoglycemia through IV glucose intake is critical for preventing neurological damage.

What is the anatomy of the adrenal cortex?

The adrenal gland is located on top of the kidney and is conical in shape. There are three zones: zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata, and zona reticularis, with the fasciculata being 75% of the total cortex. Synthesizes three different types of steroids, which are glucocorticoids (primarily cortisol in the zona fasciculata), mineralocorticoids (aldosterone in the zona glomerulosa), and sex steroids (estrogen and androgens in the zona reticularis).

What happen in hyperadrenlism?

Syndromes of adrenal hyperfunction are caused by overproduction of the three major hormones of the adrenal cortex, like Cushing syndrome (excess cortisol), hyperaldosteronism, and adrenogenital symptoms (excess androgens). Primary is caused from a disease of the adrenal cortex (adenoma) (low ACTH), and secondary is caused from hyperfunction of the anterior pituitary (high ACTH).

Cushing Syndrome: Causes thin arms and legs, extra facial hair, irregular menses, depression, anxiety, increased appetite, thin skin, moon face, red cheeks, thinning hair, stretch marks, loss of muscle mass, and fat pads on the back. Obesity and weight gain common. Hypertension happens due to the salt-retaining activity of cortisol and increased blood volume. Can be caused from cancer cells.

Hyperaldosteronism: Primary causes direct increases to aldosterone secretion, and secondary causes insulin release in response to RAAS.

What happens in hypoadrenalism?

Causes primary adrenal disease and decreased stimulation of the adrenals due to a deficiency in ACTH (secondary). Primary insufficiency is adrenal crisis, and if it becomes chronic it becomes addison disease. ACTH provocation tests are used to diagnose this type. More than 90% of cases are caused from autoimmune adrenalitis, tuberculosis, AIDS, and metastatic cancers. Symptoms occur because of inadequate circulating cortisol and aldosterone.

Adrenal Crisis: Crisis is precipitated by any form of stress that requires an immediate increase in steroid output to maintain homeostasis. Persons maintained on exogenous corticosteroids who rapidly withdrawal can precipitate adrenal crisis because of the inability of the atrophic adrenals to produce glucocorticoid hormones. Massive adrenal hemorrhage that damages the adrenal cortex sufficiently to cause acute adrenocortical insufficiency (can occur in newborns with hypoxia, on anticoagulant therapy, postsurgical development of DIC, bacterial infection like waterhouse-friderichsen syndrome). Because of the lack of cortisol, treatment is given preemptively because low cortisol levels can quickly lead to death.

Addison Disease: Clinical manifestations do not appear until at least 90% of the adrenal cortex has been compromised. Caused from diseases affecting the adrenal cortex, including lymphoma, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis, fungal infection, and adrenal hemorrhage.

Initially causes progressive weakness and easy fatigue. Eventually causes GI symptoms (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, diarrhea). Primary adrenal disease causes hyperpigmentation of the skin in sun-exposed areas and pressure points (not seen in primary pituitary of hypothalamic disease) from elevated levels of POMC, a precursor of ACTH and MSH. Salt cravings can happen because of sodium deficit.

Secondary Chronic Adrenocortical Insufficiency: Any disorder of the hypothalamus and pituitary that reduces ACTH can cause it, and has many similarities to Addison disease. Metastatic cancer, infection, infarction, or irradiation can cause it. Prolonged administration of exogenous glucocorticoids suppresses the output of ACTH and adrenal function. No hyperpigmentation, hyponatremia, or hyperkalemia.

How do thyroid hormones maintain homeostasis?

In order to produce T3 and T4… hypothalamus releases thyrotropin-releasing hormone, and the anterior pituitary releases TSH. TSH binds to TRH receptor on thyroid follicular epithelium, leading to G-protein activation and the synthesis and release of T3 and T4.

In order to reduce T3 and T4… TRH and TSH are reduced.

T3 and T4 alongside the thyroid hormone receptor creates a complex that translocate to the nucleus, binding to target genes, and initiating transcription of thyroid response elements.

What happens in hyperthyroidism?

Primary hyperthyroidism is when the thyroid over secretes thyroid hormone. Secondary hyperthyroidism is when the pituitary overstimulates the thyroid to secrete thyroid hormone, usually due to a pituitary tumor. Primary hyperthyroidism causes low TSH, while secondary causes high TSH. Ovarian tumors can also cause hyperthyroidism in an exogenous way. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis often presents as hyperthyroidism first because of the initial mass-release of stored hormones, but is still considered hypothyroidism.

Toxic Nodule: A type of primary hyperthyroidism; a nodule that becomes independent of the pituitary and secretes excess thyroid hormone.

Graves Disease: A type of primary hyperthyroidism; an autoimmune condition where antibodies bind to TSH receptors in the thyroid, which stimulates thyroid to release thyroid hormone (T3 and T4). In response to increased T3 and T4, the pituitary stops producing TSH and it falls very low. Graves disease can also cause ophthalmopathy, which is autoimmune inflammation of extraocular muscles, and pre-tibial myxedema, which is non-pitting edema. The goal is to reduce the amount of circulating thyroid hormone.

Symptoms: High metabolism, increased appetite, tachycardia (sometimes atrial fibrillation), dyspnea, heat intolerance, insomnia, diaphoresis, tremor, nervousness.

Diagnosis: Low TSH, distinguishing features, positive for anti-TSH receptor antibodies.

Treatment: Beta blockers for thyroiditis, surgical removal of the thyroid, radioactive iodine. Antithyroid medications are used to block thyroid peroxidase, but there is 3 months stored supply of thyroid hormone stored in the thyroid, so effects

What happens in hypothyroidism?

Due to the dysfunction of the thyroid gland. Can cause goiter, which is an enlarged thyroid (not always associated with hypothyroidism), and can be present in hyperthyroid states. Myxedema happens with prolonged thyroid deficiency, which is non-pitting edema due to the accumulation of glycosaminoglycan s in the interstitial space, which is controlled by thyroid hormones. If this is uncontrolled, it can lead to coma. Low T3 and T4 causes weight gain, bradycardia, hypoventilation, cold intolerance, fatigue, weakness, myalgia, anemia.

Primary Hypothyroidism: Can be congenital or acquired, when thyroid under secretes thyroid hormone, often from underdevelopment. This is the most common type of hypothyroidism. Primary hypothyroidism results in high TSH because thyroglobulin can still form. Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis is an autoimmune condition against TOP and TG, leading to lymphocytes attacking the thyroid gland and resulting in partial or full loss or function. This is the most common cause of acquired hypothyroidism. Can be caused from thyrotoxic drugs, iodine deficiency (which prevents T3 and T4 production), post surgical damage, or radiotherapy.

Secondary Hypothyroidism: Due to pituitary pathology through infection, inflammation, infiltration, hemorrhage, or a tumor. Uncommon and often from head trauma.

Tertiary Hypothyroidism: Due to hypothalamic underactivity or tumor.

Treatment: Restores thyroid hormone (T3 and T4), or a combination (desiccated thyroid, liotrix), iodine supplementation.

What makes up the GI system?

The GI system goes from the mouth to the rectum, which is specialized for digestion and/or absorption. Regions are specialized depending on their function: oral cavity, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and accessory organs like the liver and pancreas.

Disorders of these systems can cause dysphagia, esophageal/abdominal pain, vomiting, intestinal gas, and alterations in bowel patterns (constipation, diarrhea).

What is stomatitis?

Ulcerative inflammation of the oral mucosa that may involve buccal mucosa, lips, and palate. This can be caused from mechanical trauma, exposure to irritants, pathogens, tobacco, and medications (like chemotherapy). Nutritional and vitamin deficiencies make contraction more likely. The most common form is cold sores from HSV type I, which leave behind painful ulcers. HSV type 2 is mostly genital-related, but may cause type I irritation.

What are some disorders of the esophagus?

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): The backflow of gastric contents into the esophagus through the LES, causing esophageal inflammation. The upper esophageal sphincter is connected to skeletal muscle, while the lower sphincter is made of smooth muscle below the diaphragm. Relaxation occurs intermittently with swallowing, but in GERD, the LES exerts less pressure than the UES. Can be caused from hiatal hernia (LES slides into thorax), from imbalances in progesterone and ETOH (LES relaxes more), or from pressure in the stomach. The extent of damage depends on the frequency, duration, and potency of the acidity of the gastric juices being refluxed.

Symptoms: GERD may or may not be symptomatic. In early stages, postprandial and nocturnal heartburn, and waterbrash, causing regurgitation when bending or lying down. In middle stages, reactive airway disease, hoarseness, cough, and dysphagia. In late stages, strictures and bleeding from esophageal ulcers or varices occurs.

Treatment: Goal is to reduce number of episodes, increase protective lining, decrease acidity of reflux, and increase clearance of esophageal contents. Diet should include small meals with high protein and low fat, limiting bedtime snacks. Avoid high acid foods, like chocolate, smoking, fat, ETOH, and tight clothing. Elevating bed and losing weight may help as well. Treating ulcers and decreasing acid through medications and lifestyle changes. Anything to helps increase pressure of the LES.

Hiatal Hernia: Defect in the diaphragm that allows a portion of the stomach to pass through the diaphragmatic opening into the throat. There are two types: sliding (stomach slips into the thorax) and paraoesophageal (stomach rolls through the diaphragmatic defect). Mixed includes both of these types, but sliding hernias are far more common. Risk increases with age, with 60% of people over age 60 having one, but it’s more common in women than men. Individuals are also predisposed to GERD.

Mallory-Weiss Syndrome: Bleeding caused by a tear in the mucosa or submucosa of the cardia or lower portion of the esophagus. The tear is usually longitudinal. This is caused from forceful or prolonged vomiting where the upper esophageal sphincter fails to relax. 75% of individuals are men with a history of excess alcohol consumption, but may be caused from trauma, coughing, straining, esophagitis, gastritis, and use of polyethylene glycol. Symptoms include vomiting blood and passing large amounts of blood in the rectum. Bleeding can be mild to severe.

Esophageal Varices: Rupture of the esophageal varices leads to a serious complication of cirrhosis-induced portal hypertension and carries a high mortality, often associated with alcoholism in the western world.

What are some disorders of the stomach?

Elevated Prostaglandins: Prostaglandins increase mucus secretion in the stomach. This can be caused from prolonged NSAIDS, COX-2 inhibitors, glucocorticoids, and tobacco and alcohol use.

Stress Related Mucosal Disease: Occurs during severe physiologic stress, often related to local ischemia. This can come from shock (sepsis, burns, hemorrhage), decreased stomach perfusion (lower mucosal protection), or ulceration.

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome: Normal factors that cause an increase of stomach acid includes stress, histamine, caffeine, acetylcholine, gastrin. However, this syndrome is caused from a pancreatic tumor (gastrinoma), which secretes excess gastrin. This results in ulcerations at multiple sites in the body.

Gastritis: Inflammation of the lining of the stomach. Acute gastritis may be triggered by ingestion of toxins or as a consequence of viral, bacterial, or autoimmune illnesses. Often related to H. pylori infections.

Gastroenteritis: Inflammation of the stomach and small intestine. This can be acute or chronic. Commonly occurs as a result of a direct infection of the GI tract lining. A self-limited disease with diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and pain, nausea, and vomiting. May also be associated with increased temperature (stomach-flu).

Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD): Disorder of the upper GI tract (stomach and duodenum) caused by the action of pepsin and hydrochloric acid. H. Pylori is the major precipitant of PUD, along with NSAIDS. Gastric ulcers should always be biopsied to rule out gastric ca. The breakdown of the normally helpful epithelial lining leads to the stomach acid perforating the tissue, causing damage. Inappropriate excess secretion of acid is a major contributor as well. Clearance of H. pylori helps with ulcer healing, because H. pylori is a bacteria that thrives in acidic conditions.

Gastric Ulcers: Pain immediately after eating due to irritation of the acidic gastric contents.

Duodenal Ulcers: Pain hours after a meal due to gastric emptying.

Symptoms: Epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting (with blood), melena, appetite changes. Bleeding occurs in 15-20% of cases, and is the most frequent complication (which results in 25% of ulcer-related deaths) and may be the first indication. Perforation is in 5% of cases (accounting for 33% of related deaths). Severe ulcer disease causes acute abdominal pain and air under the diaphragm. Obstruction is mostly in chronic ulcers, and is secondary to edema and scarring. This occurs in 2% of patients, often related to pyloric channel ulcers, but may also happen with duodenal ulcers; incapacitating abdominal pain and possible total obstruction with intractable vomiting.

Treatment: Medications to neutralize acid, including parietal cell inhibition through proton pump inhibitors, and decreased stimulation of parietal cells with H2 blockers (increases acid through histamine binding to it). Vagotomies sever parasympathetic input to acid-secreting cells. Antibiotics will be needed to treat H. Pylori. You can increase mucosal defense from things that mimic mucus, like sucralfate.

What is the difference between UC and Chron’s?

IBD: A chronic condition resulting from inappropriate mucosal immune activation in genetically predisposed individuals. IBD results from a combination of abnormalities in immune regulation, host-microbe interactions, and epithelial barrier functions in genetically susceptible individuals. Disorders switch between exacerbation and remission. Conditions are treated using corticosteroids, immunodilators, antibiotics, surgery, and diet.

Ulcerative Colitis: A type of IBD. Inflammatory disease of the mucosa of the rectum and colon. Mediated by cytotoxic T cells towards the crypts of Lieberkühn, but damage extends, bringing in leukocytes and abscesses as a result. These abscesses can combine and become larger. This includes total colitis (1/5th of all cases), subtotal disease beyond sigmoid, or limited to the rectum and rectosigmoid. UC represents a continual area of inflammation, and ranges from mild to severe. Changes are most severe in the rectum and extend for a variable extent around the colon. Walls appear normal and include marked pseudopolyps and superficial broad-based ulcers. There is the potential for malignancy and toxic megacolon. Bloody stool is more common. Systemic corticosteroids are the mainstay treatment, along with anti-TNF, but these treatments lead to immunosuppression.