PANIC DISORDER AND AGROPHOBIA AB p

1/37

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

38 Terms

PANIC DISORDER

a debilitating anxiety disorder in which individuals experience severe, unexpected panic attacks

They may think they’re dying or otherwise losing control

Accompanied by a closely related disorder called agoraphobia

AGORAPHOBIA

fear and avoidance of situations in which a person feels unsafe or unable to escape to get to home or to a hospital in the event of developing panic, panic-like symptoms, or other physical symptoms

People develop this because they never know when these symptoms might occur

CLINICAL DESCRIPTION

In DSM-IV, panic disorder and agoraphobia were integrated into one disorder called panic disorder with agoraphobia, but it was discovered that many people experience panic disorders without developing agoraphobia and vice versa.

Many people who have panic attacks do not necessarily develop panic disorder.

To meet criteria for panic disorder, a person must experience an unexpected panic attack and develop substantial anxiety over the possibility of having another attack or about the implications of the attack or its consequences.

The person must think that each attack is a sign of impending death or incapacitation

Agoraphobia

Coined in 1871 by Karl Westphal, a German physician, and, in the original Greek, refers to fear of the marketplace

Agora = the Greek marketplace (a busy, bustling area)

Most agoraphobic avoidance behavior is simply a complication of severe, unexpected panic attacks

TYPICAL SITUATIONS AVOIDED BY PEOPLE WITH AGORAPHOBIA

Shopping malls | Being far from home |

Cars (as driver or passenger) | Staying at home alone |

Buses | Waiting in line |

Trains | Supermarkets |

Subways | Stores |

Wide streets | Crowds |

Tunnels | Planes |

Restaurants | Elevators |

Theaters | Escalators |

Other methods of coping with panic attacks

using (and sometimes abusing) drugs and/or alcohol

Not avoiding agoraphobic situations but enduring them with “intense dread”

interoceptive avoidance

Most patients with panic disorder and agoraphobic avoidance also display another cluster of avoidant behaviors, it is the avoidance of internal physical sensations

Behaviors involve removing oneself from situations that might produce the physiological arousal

INTEROCEPTIVE DAILY ACTIVITIES TYPICALLY AVOIDED BY PEOPLE WITH AGORAPHOBIA

Running up flights of stairs | Having a sauna |

Walking outside in intense heat | Hot, stuffy rooms/cars |

Having showers with the doors and windows closed | Getting involved in “heated debates |

Hot, stuffy stores or shopping malls | Hiking |

Walking outside in very cold weather | Sports |

Aerobics | Drinking coffee/caffeinated drinks |

Lifting heavy objects | Sexual relations |

Dancing | Watching horror movies |

Eating chocolate | Eating heavy meals |

Standing quickly from a sitting positions | Getting angry |

Watching exciting movies/sports |

Panic Disorder (PD) Prevalence:

2.7% of the population meet PD criteria in a given 1-year period

4.7% meet PD criteria at some point in their lives, with two-thirds being women

Agoraphobia without Panic Attacks:

1.4% of the population develop agoraphobia without experiencing a full-blown panic attack

Gender Distribution in Agoraphobia:

75% or more of agoraphobia sufferers are women

Women are more socially permitted to report fear and avoid situations, while men are expected to be braver

Age of Onset

Typical Onset: PD usually begins in early adulthood, from midteens to around 40 years, with a median onset between 20-24 years

Children:

Prepubescent children rarely experience unexpected panic attacks or PD, though some have hyperventilation symptoms mistaken for panic attacks

These children often do not report fear of dying or losing control, possibly due to limited cognitive development

Elderly Population:

PD and comorbid PD with agoraphobia prevalence decreases with age, from 5.7% (ages 30–44) to 2.0% or less (after age 60)

Anxiety in the elderly focuses on health and vitality

Gender-Specific Coping Mechanism

Men with Panic Attacks:

Cultural disapproval of fear in men leads many to avoid reporting panic attacks

Coping mechanism: A large proportion of men use alcohol to cope, which is culturally acceptable but leads to dependency

Consequences

Alcohol abuse can mask underlying PD or agoraphobia, complicating diagnosis

Treatment challenge: even after successful addiction treatment, the anxiety disorder requires separate treatment

CULTURAL INFLUENCES

Anxiety manifests differently across cultures, influenced by cultural beliefs and norms.

Susto:

Ataques de Nervios

Kyol Goeu (Wind Overload):

Susto:

A fright disorder in Latin America characterized by physical symptoms (e.g., sweating, increased heart rate, insomnia) without reported anxiety or fear

Ataques de Nervios

Common among Hispanic Americans, particularly from the Caribbean.

Symptoms resemble panic attacks but may include unique expressions like shouting uncontrollably or bursting into tears

Kyol Goeu (Wind Overload)

Observed in Khmer and Vietnamese refugees in the U.S., who experience high rates of panic disorder.

Panic attacks are associated with orthostatic dizziness (dizziness from standing quickly) and sore neck.

Cultural Belief: Catastrophic thinking focuses on kyol goeu (excess wind or gas in the body), believed to potentially cause blood vessel rupture

NOCTURNAL PANIC

anic attacks occurring during sleep, often between 1:30am and 3:30am

Approximately 60% of individuals with panic disorder experience nocturnal panic attacks

Some individuals develop fear of sleep due to these attacks, mistakenly believing they are dying

Nocturnal panic attacks occur during delta wave or slow wave sleep, the deepest stage of sleep, several hours after falling asleep

Monitored in sleep laboratories using an electroencephalograph (EEG) to track brain waves

Cause: the transition to slow wave sleep produces physical sensations of “letting go,” which are frightening for individuals with panic disorder

Distinction from nightmares

Nightmares occur during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, later in the sleep cycle, unlike nocturnal panic

Patients report no dream activity during nocturnal panic, ruling out repression of trauma-related dreams

Conditions Mistaken for Nocturnal Panic

CONDITION | DESCRIPTION | KEY DIFFERENCES |

Sleep Apnea | Breathing interruption during sleep, feeling like suffocation, common in overweight individuals | Involves a cycle of awakening and falling back asleep, unlike nocturnal panic |

Sleep Terrors | Children awaken imagining being chased, often screaming or leaving bed, with no memory of the event | Occur in stage 4 sleep (linked to sleepwalking), not delta wave sleep; individuals do not wake or recall the event |

Isolated Sleep Paralysis | Inability to move during the sleep-wake transition, with terror and possible hallucinations, resembling a panic attack | Occurs during REM sleep spillover; more common in African Americans (40.2% in general population, 44.3% in psychiatric samples) and Asian American students (39.9%) vs. 7.6% in the general population |

ISOLATED SLEEP PARALYSIS

Known as “the witch is riding you,” more prevalent among African Americans

Associated conditions:

African Americans with isolated sleep paralysis have higher rates of trauma, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder

CAUSES

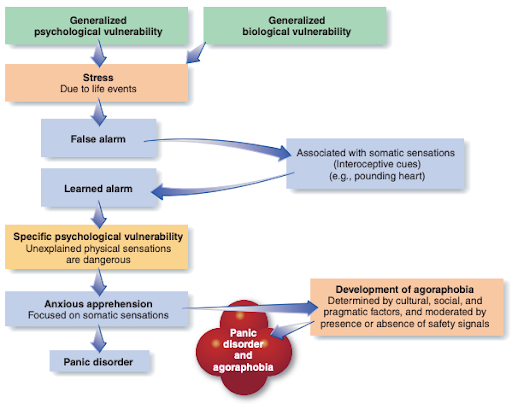

Panic disorder causes involves a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors (triple vulnerability model)

Individuals inherit a tendency to be neurobiologically overreactive to daily life stressors (e.g., job stress, death of a loved one, divorce, or positive events like graduation, marriage, or job changes).

Some are more prone to emergency alarm reactions (i.e., unexpected panic attacks) in response to stress

LEARNED ALARMS

ues that become associated with a number of different internal and external stimuli through a learning process

SPECIFIC PSYCHOLOGICAL VULNERABILITY

Tendency to perceive unexpected bodily sensations as dangerous, increasing the likelihood of panic disorder

Example: Women with a history of physical disorders and health anxiety in childhood are more likely to develop panic disorder than social anxiety disorder.

Model for the cause of Panic disorder with or without agoraphobia

David Clark’s Cognitive Model (1986, 1996)

Emphasizes specific psychological vulnerability where individuals catastrophically interpret normal physical sensations (e.g., rapid heartbeat post-exercise).

This anxiety triggers more physical sensations via the sympathetic nervous system, creating a vicious cycle leading to a panic attack

Prevalence of Panic Attacks

8%–12% of the population experience occasional unexpected panic attacks, often during intense stress

Only about 5% develop anxiety over future attacks, meeting panic disorder criteria, due to generalized psychological vulnerability.

Example: Professional golfer Charlie Beljan experienced a panic attack during a PGA tournament in 2012, mistaking it for a heart attack, yet continued playing with paramedics present

Contrast: Those who do not develop anxiety attribute attacks to temporary events (e.g., argument, bad food, stressful day) and resume normal life

Psychodynamic Hypotheses

Hypothesis: Early object loss or separation anxiety in childhood might predispose individuals to panic disorder or agoraphobia in adulthood.

Separation anxiety: Fear experienced by a child due to threatened or actual separation from a caregiver (e.g., mother or father).

Dependent personality tendencies: Often observed in agoraphobia, hypothesized as a reaction to early separation.

Evidence: Little support for separation anxiety being more common in panic disorder or agoraphobia compared to other psychological disorders or non-clinical populations

Broader Impact: Early separation trauma may predispose individuals to psychological disorders in general, but not specifically to panic disorder or agoraphobia.

MEDICATION

Several medications targeting neurotransmitter systems

are effective for panic disorder:

High-potency benzodiazepines (e.g., alprazolam (Xanax)).

Selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g., Prozac, Paxil).

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (e.g., venlafaxine)

SSRIs (e.g. Prozac, Paxil)

Indicated drug based on evidence; effective for panic disorder | Sexual dysfunction in 75% or more of users |

High-potency Benzodiazepines (e.g. Alprazolam (Xanax))

Quick-acting relief for panic attacks | Psychological and physical dependence; addiction risk; adverse effects on cognitive and motor functions (e.g., reduced ability to drive or study); not strongly recommended |

SNRIs (e.g. Venlafaxine)

Effective for panic disorder | Viable alternative to SSRIs |

Treatment Outcomes and Challenges

Effectiveness: Approximately 60% of panic disorder patients remain panic-free while on an effective drug

Discontinuation:

20% or more of patients stop medication before treatment completion

Relapse Rates:

Approximately 50% relapse after stopping medication

Up to 90% relapse after discontinuing benzodiazepines

PSYCHOLOGICAL INTERVENTION

Psychological treatments are highly effective for panic disorder, addressing both panic attacks and agoraphobic avoidance. Early treatments targeted agoraphobic avoidance using exposure-based strategies to confront feared situations.

EXPOSURE-BASED TREATMENTS

involve gradually exposing patients to feared situations to demonstrate they are safe, convincing patients on an emotional level through reality testing

Methods:

Therapist accompaniment during exposure exercises or guiding patients to structure their own

Exercises arranged from least to most difficult

Often combined with anxiety-reducing coping mechanisms like relaxation or breathing retraining

Outcomes:

Up to 70% of patients show substantial improvement, with reduced anxiety, panic, and agoraphobic avoidance

Few achieve complete cure, as some anxiety or panic attacks persist at a less severe level

SITUATION-EXPOSURE TASKS (FROM LEAST-MOST DIFFICULT)

Shopping in a crowded supermarket for 30 minutes alone | |

Walking five blocks away from home alone | |

Driving on a busy highway fro 5 miles with spouse and alone | |

Eating in a restaurant, seated in the middle | |

Watching a movie while seated in the middle of the row |

PAIN CONTROL TREATMENT (PCT)

directly targets panic disorder, even without agoraphobia, by exposing patients to interoceptive (physical) sensations resembling panic attacks

Techniques:

Introducing mini panic attacks in therapy (e.g., exercise to elevate heart rate, spinning to cause dizziness)

Cognitive therapy to modify unconscious attitudes and perceptions about the dangerousness of harmless situations

Optional relaxation or breathing retraining, though less used as they are often unnecessary

Effectiveness:

Highly effective, with most patients maintaining improvement for at least 2 years

Follow-up:

Standard exposure exercises can address remaining agoraphobic behavior

Some patients relapse over time, prompting research into long-term strategies

STUDY ON BOOSTER SESSIONS:

Participants: 256 patients with panic disorder and varying agoraphobia levels completed 3 months of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

Design: Responders were randomized to 9 months of monthly booster sessions (n=79) or no booster sessions (n=78), followed by 12 months without treatment

Outcomes:

Booster sessions: 5.2% relapse rate, reduced work and social impairment

No booster sessions: 18.4% relapse rate at 21-month follow-up

Conclusion: Booster sessions reinforce treatment gains, improving long-term outcomes for panic disorder and agoraphobia

Applicability: Similar treatments effective for children and older adults