Muscle Structure and Adaptation

1/8

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

9 Terms

Skeletal muscle: 2 main groups

Skeletal muscle fibres are classified by contraction speed into two main types

Slow twitch (Type I)

Fast twitch (Type II)

Slow twitch fibres (Type I)

Fatigue resistant

Moderate maximum force

Primarily oxidative metabolism

Many mitochondria

Rich vascularisation

Small fibre diameter

High myoglobin content → red muscle

Fast twitch fibres (Type II)

Fatigue rapidly

High maximum force

Glycolytic (Type IIx) or mixed oxidative–glycolytic (Type IIa)

Fewer mitochondria

Sparser vascularisation

Larger fibre diameter

Low myoglobin content → white muscle

Myofibril proteins

Muscle fibres all share the same basic sarcomere structure, but their functional behaviour changes because they express different protein isoforms. These isoforms alter how fast and how sensitively the contractile machinery works.

Calcium sensitivity (thin filament regulation)

Troponin and tropomyosin exist in different isoforms.

Different isoforms change how easily the thin filament responds to calcium.

Higher calcium sensitivity means force develops at lower calcium levels.

This tuning affects how smoothly and how long a fibre can contract.

ATP hydrolysis rate (thick filament motor speed)

Myosin heavy chain isoforms differ in ATPase activity.

ATPase rate determines cross-bridge cycling speed.

Faster ATP hydrolysis produces faster contraction but quicker fatigue.

Slower ATP hydrolysis produces slower contraction but greater endurance.

Slow-twitch fibres (Type I)

Express type I myosin heavy chain

Have low ATPase activity

Show slow cross-bridge cycling

Are specialised for sustained, fatigue-resistant contractions

Fast-twitch fibres (Type II)

Express type II myosin heavy chain

Have high ATPase activity

Show rapid cross-bridge cycling

Are specialised for fast, powerful contractions

Muscle fibre type composition can be different in different muscles and can adapt over time to the needs of the body

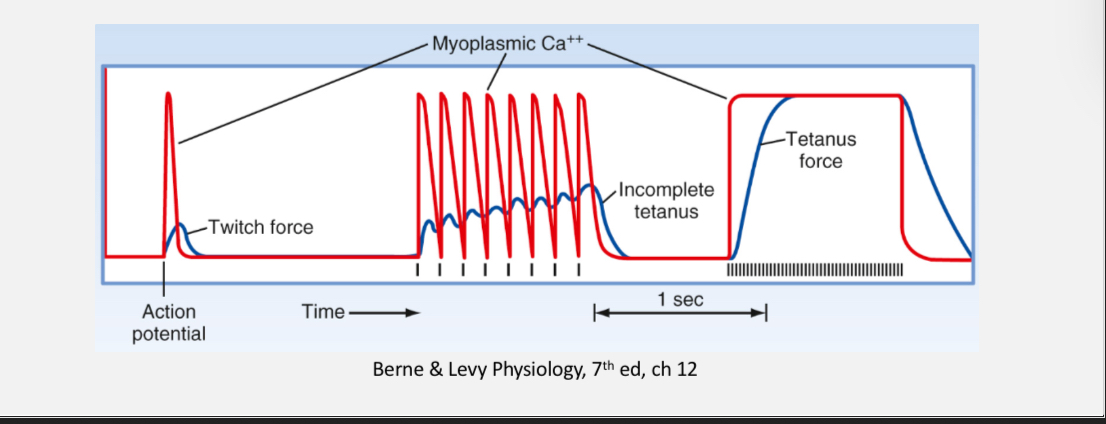

Temporal summation in muscle fibres

Repeated action potentials cause twitches to overlap in time.

Calcium is not fully removed between stimuli, so force adds together.

Low–moderate frequency stimulation produces incomplete tetanus.

Very high frequency stimulation produces fused tetanus with sustained maximal force.

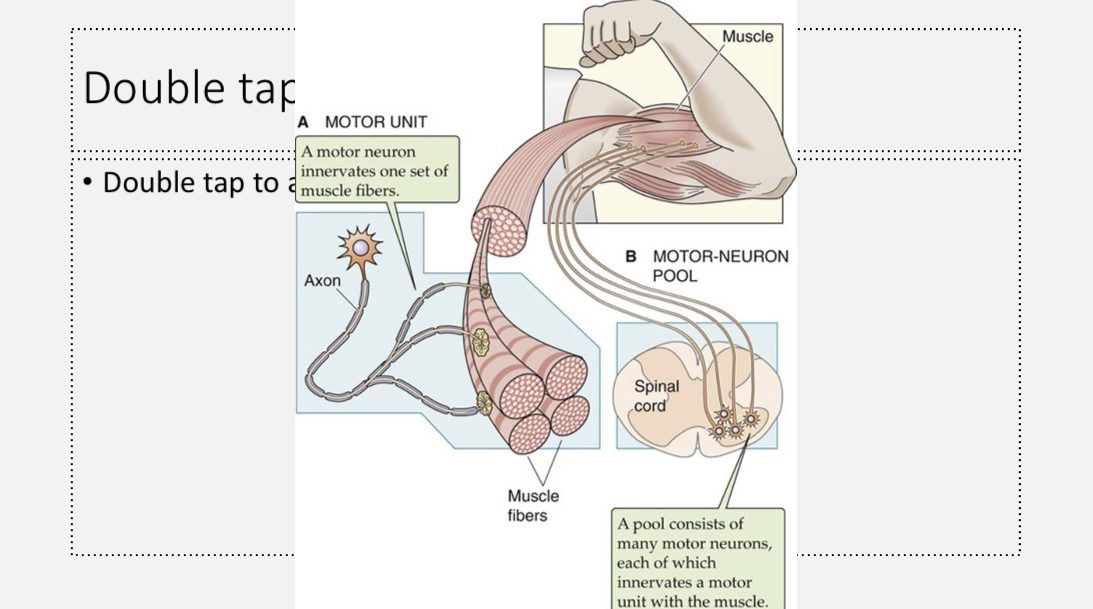

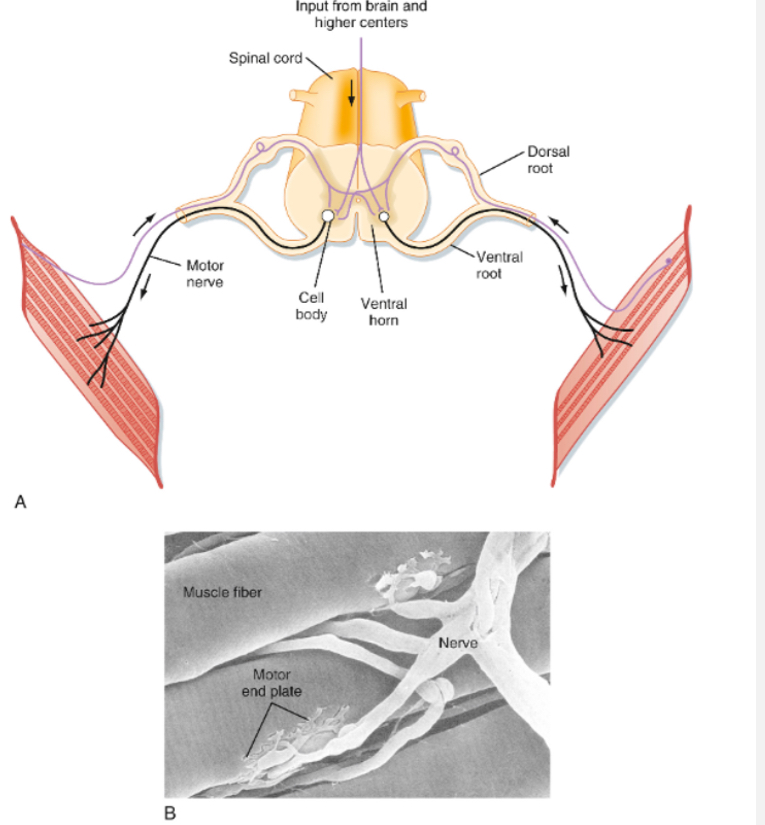

Motor Unit

Muscle force is controlled at the level of the motor unit.

One motor unit consists of a single motor neuron and all the muscle fibres it innervates.

A motor neuron belongs to only one motor unit, and each muscle fibre is innervated by only one motor neuron.

Motor units vary in size, from a few fibres to hundreds, depending on the muscle’s function.

The size of the motor neuron correlates with the size of its motor unit.

All muscle fibres within a motor unit are usually the same fibre type.

The motor pool is the collection of all motor neurons innervating a single muscle.

Muscle tension increases by recruiting more motor units from the motor pool.

Summation in fast and slow motor units

Fast motor units require higher firing frequencies to produce fused tetanic force.

• Slow motor units reach tetanus at lower firing frequencies.

• Slow motor units are recruited first during increasing force demands.

• Fast motor units are recruited later to generate higher force levels.

Slow-twitch fibres have long-lasting contractions and relax slowly.

• Calcium remains elevated for longer between action potentials.

• Twitches overlap even at low firing frequencies, allowing fusion.

• This means slow motor units reach tetanus at lower firing rates.

• Fast-twitch fibres relax quickly and clear calcium rapidly.

• They require much higher firing frequencies for twitches to fuse.

Skeletal Muscle Tone

Skeletal muscles at rest maintain a low level of continuous contraction called muscle tone.

Muscle tone depends on intact motor innervation.

Loss of innervation causes complete relaxation, producing flaccid muscle.

Resting tone is generated by reflex activity from muscle spindles via spinal reflex arcs.

Cutting sensory (dorsal) roots abolishes resting muscle tone.

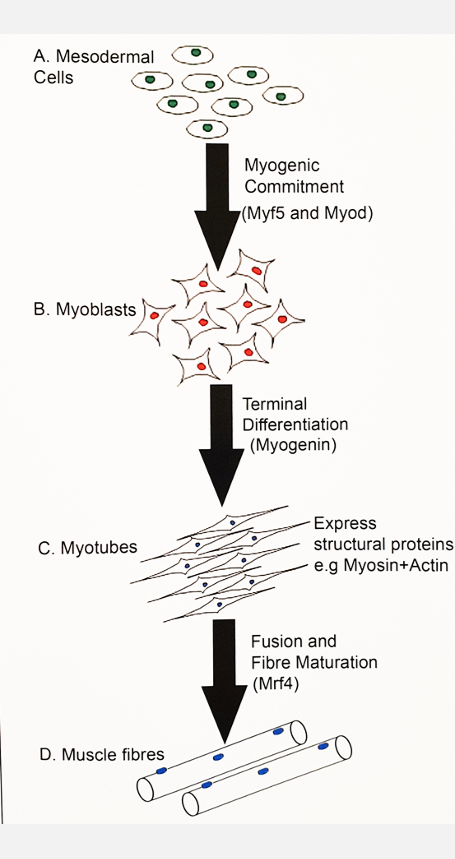

Myogenesis

Myogenesis is the process by which skeletal muscle fibres are formed from precursor cells.

Step 1: Commitment to muscle

Mesodermal precursor cells receive local (paracrine) signals.

These signals switch on muscle-specific transcription factors (MyoD, Myf5).

Once these genes are on, the cell is committed to becoming muscle.

At this point the cell is called a myoblast.

Step 2: Myoblast proliferation

Myoblasts divide to increase cell number.

They are still immature and not yet muscle fibres.

Step 3: Exit from the cell cycle

Myoblasts stop dividing.

Expression of myogenin(muscle specific TF) increases.

This signals terminal differentiation, meaning the cell will now become muscle and not divide again.

Step 4: Myotube formation

Differentiating myoblasts start making muscle proteins such as actin and myosin.

Myoblasts line up next to each other.

They fuse together to form long, multinucleated cells called myotubes.

Step 5: Muscle fibre maturation

Myotubes continue to fuse and grow.

Sarcomeres organise inside them.

Mature skeletal muscle fibres are formed.

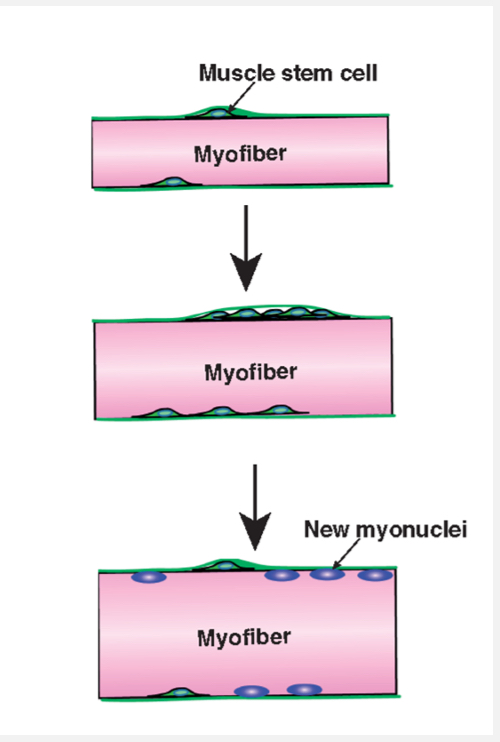

Satellite cells

Some cells remain as satellite cells.

These are muscle stem cells.

They allow muscle growth after birth and repair after injury.

Postnatal muscle growth: Hypertrophy and Hyperplasia

Hypertrophy:

Postnatal muscle growth mainly occurs by hypertrophy, meaning existing muscle fibres increase in size.

Hypertrophy involves satellite cells, which are muscle stem cells.

Satellite cells proliferate and donate nuclei to existing muscle fibres.

Added nuclei support increased protein synthesis and fibre enlargement.

Muscle fibres are multinucleated and maintain a stable nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio.

Satellite cells return to a resting (quiescent) state when not needed.

Hyperplasia:

Hyperplasia is growth by forming new muscle fibres.

There is some evidence for hyperplasia in animal studies.

In humans, its contribution is uncertain and hypertrophy is the dominant mechanism.

Ageing Muscle: Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia is the age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass.

• It involves atrophy of muscle fibres and reduced muscle strength.

• It can be worsened by disease or prolonged immobilisation.

• There is reduced satellite cell number and activation.

• Muscles show anabolic resistance, with a blunted protein synthesis response to hormones and resistance exercise.

• Resistance training can slow or partially reverse sarcopenia.

(Anabolic builds muscle; catabolic breaks muscle down.)