Chapter 9: Addition Reactions of Alkenes

1/96

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

97 Terms

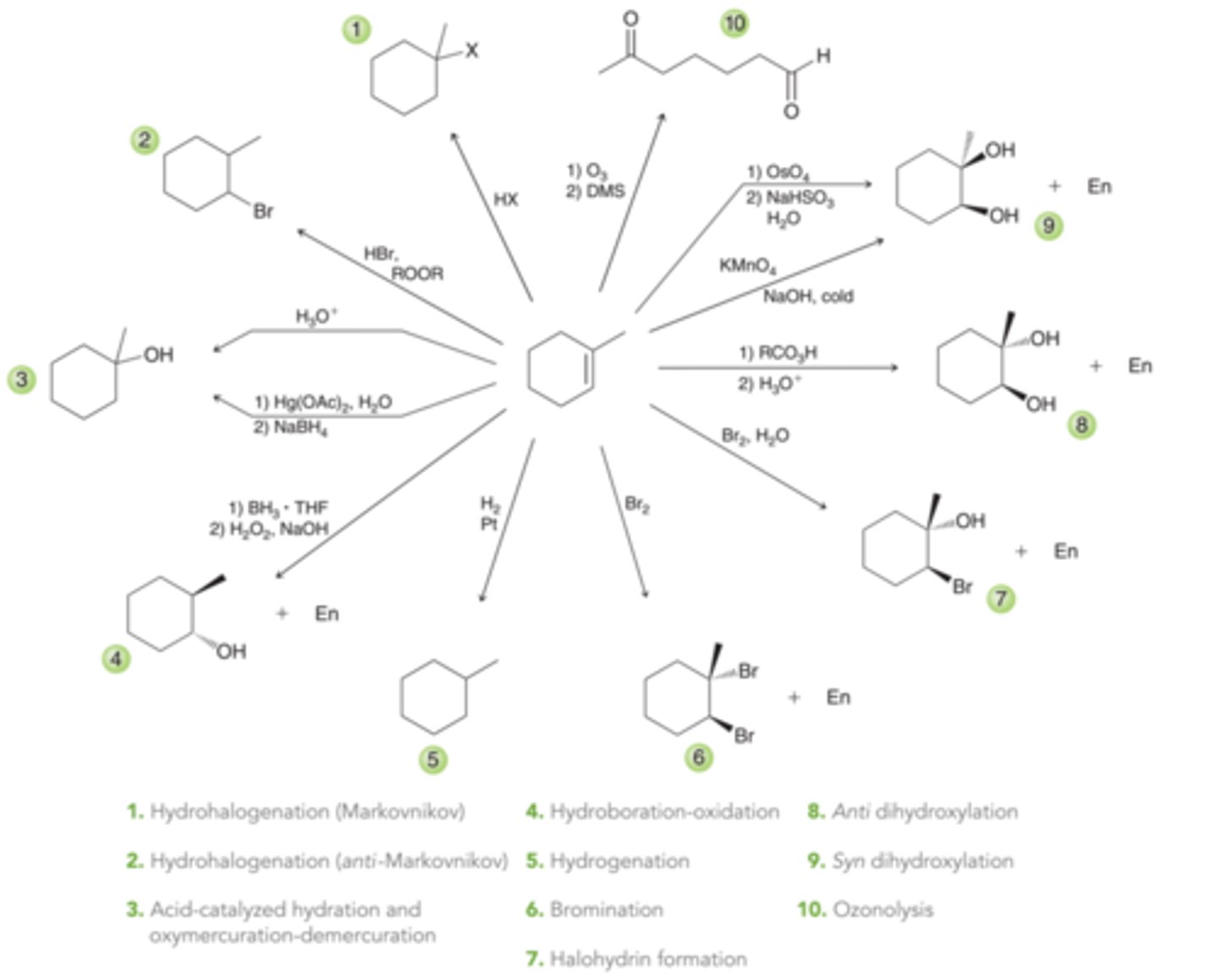

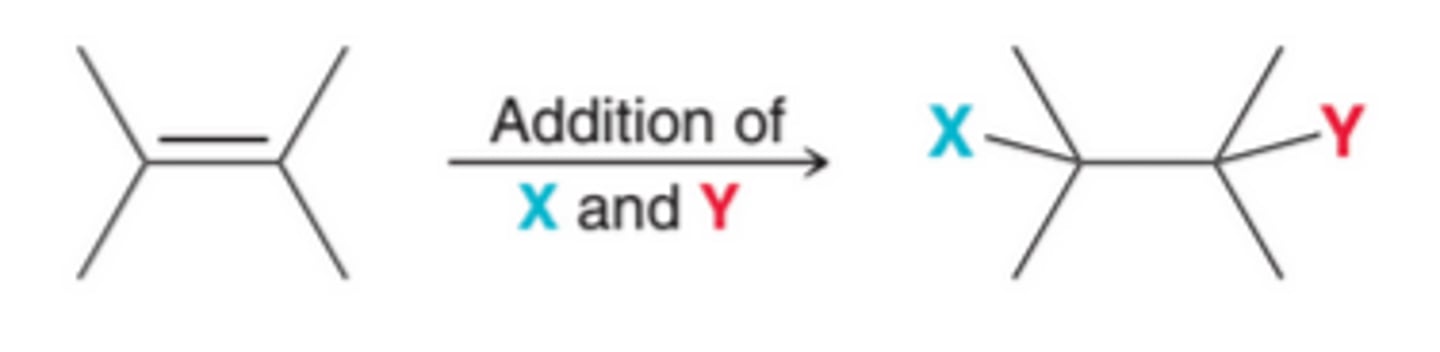

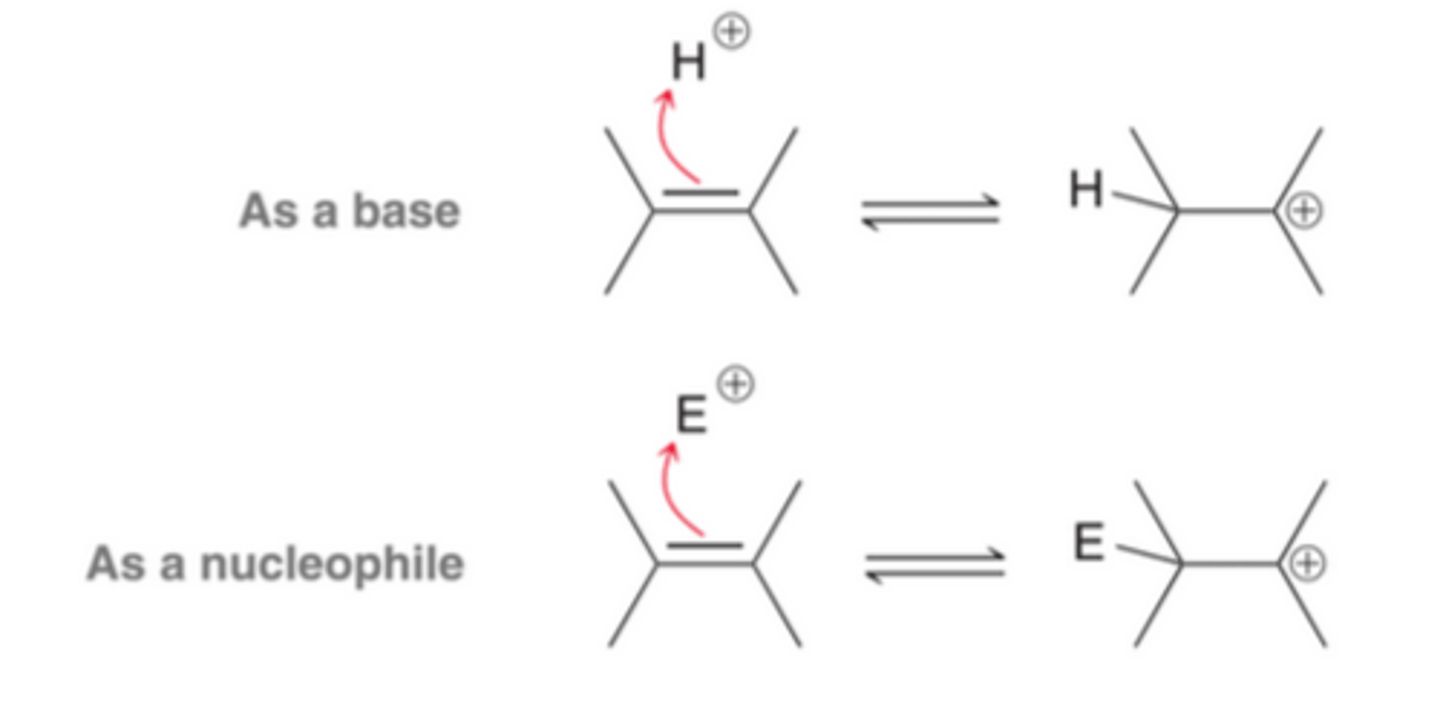

Addition Reactions

Common reactions of alkenes, characterized by the addition of two groups across a double bond. In the process, the pi bond is broken

Special Names for Some Addition Reactions

Some addition reactions have special names that indicate the identity of the two groups that were added

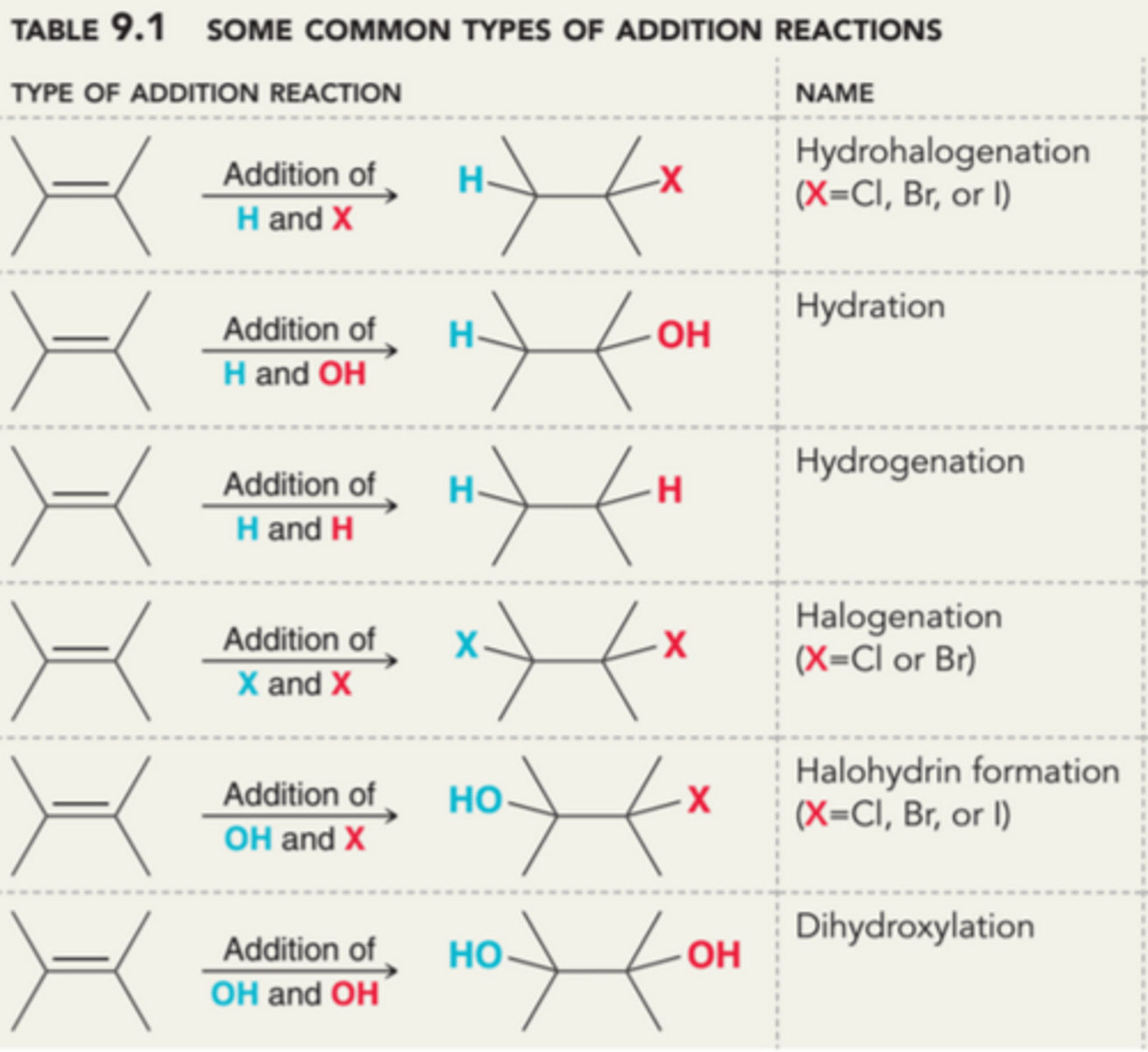

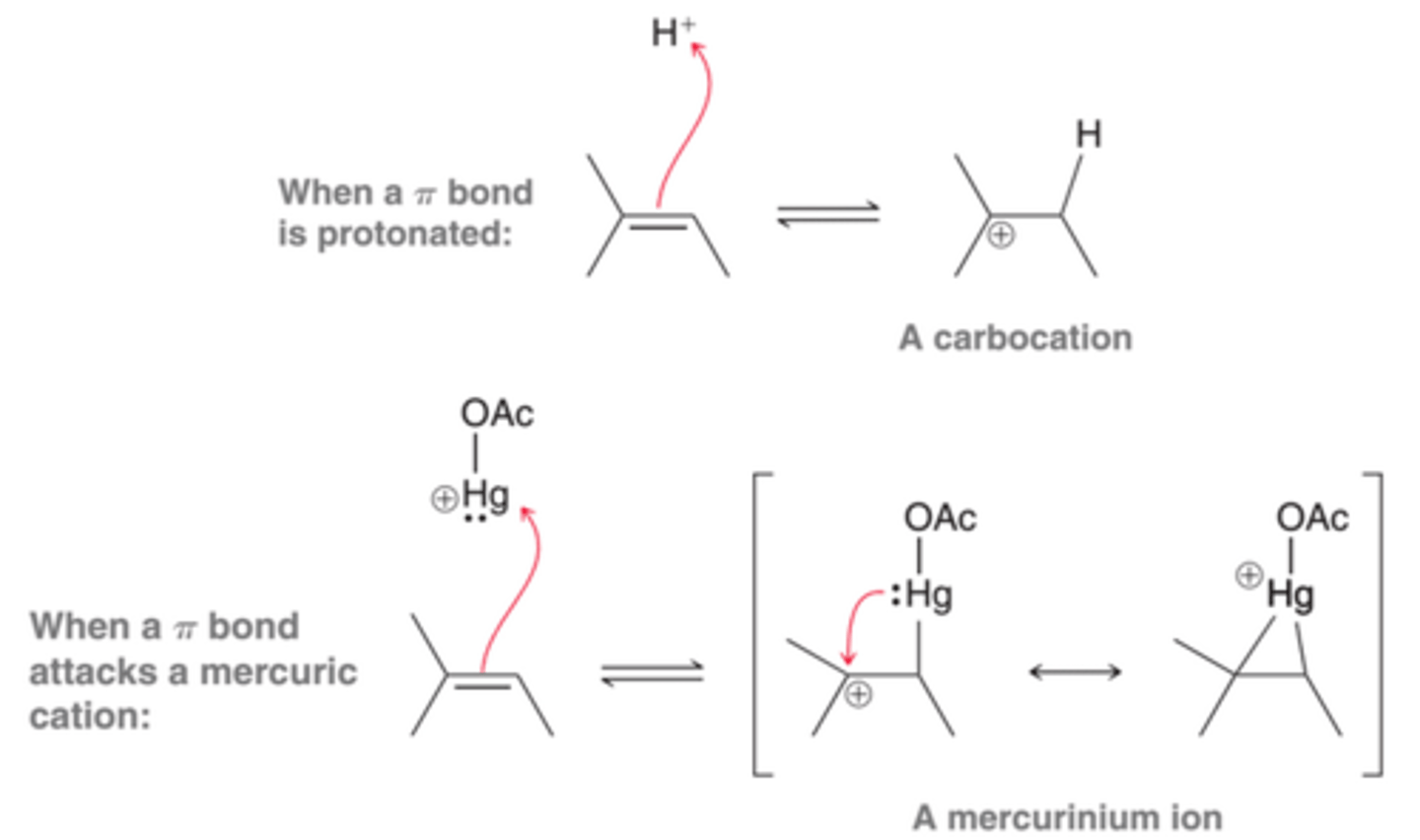

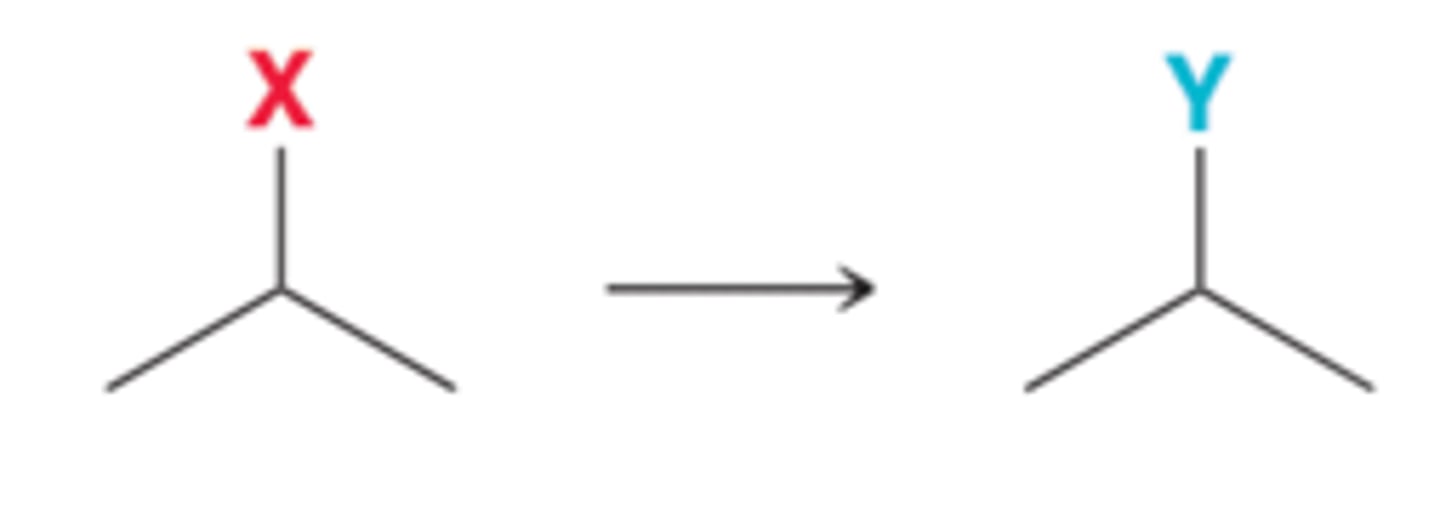

Pi Bonds as Bases and Nucleophiles

Many different addition reactions are observed for alkenes, enabling them to serve as synthetic precursors for a wide variety of functional groups. The versatility of alkenes can be directly attributed to the reactivity of pi bonds, which can function either as weak bases or as a weak nucleophiles. The 1st process in this image illustrates that pi bonds can be readily protonated, while the second process illustrates that pi bonds can attack electrophilic centers

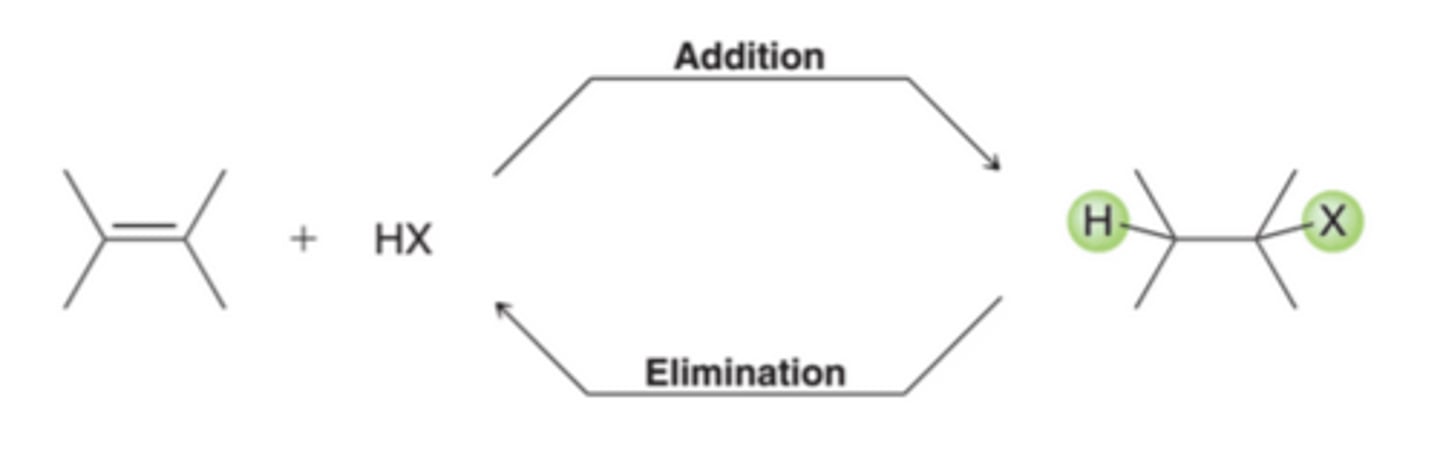

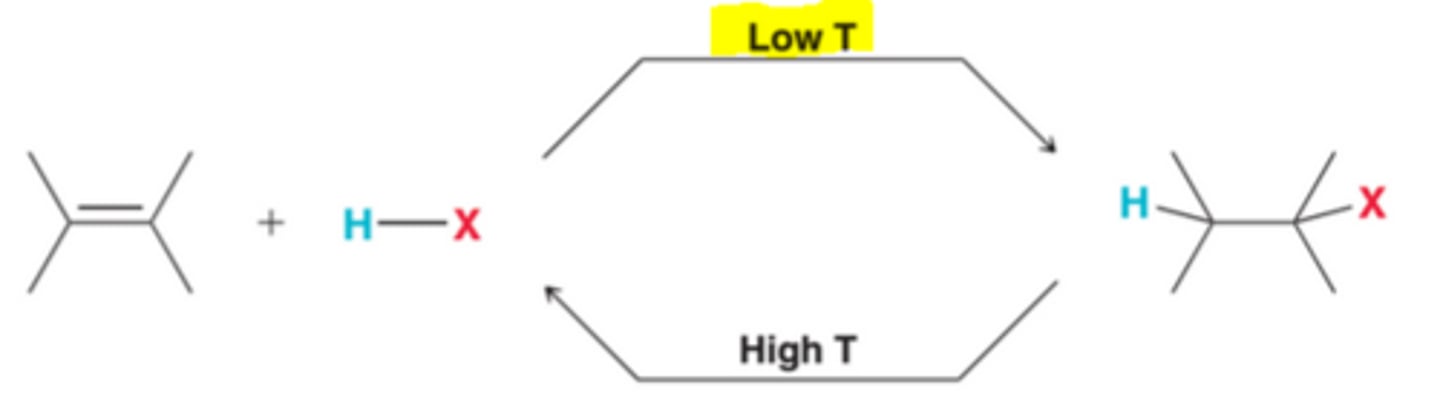

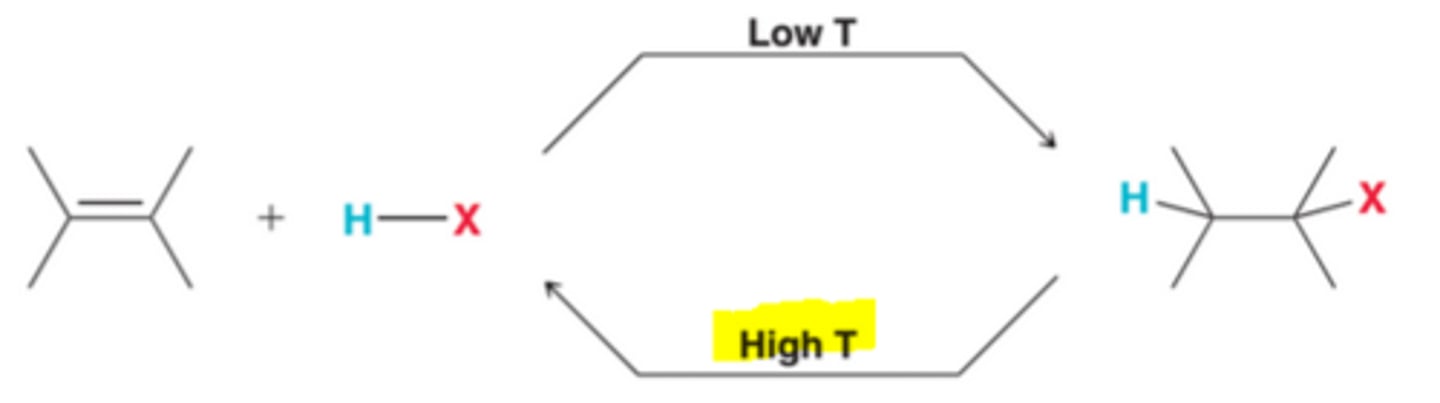

Addition vs. Elimination Reactions

In many cases, an addition reaction is simply the reverse of an elimination reaction. These two reactions represent an equilibrium that is temperature dependent. Addition is favored at low temperature, while elimination is favored at high temperatures.

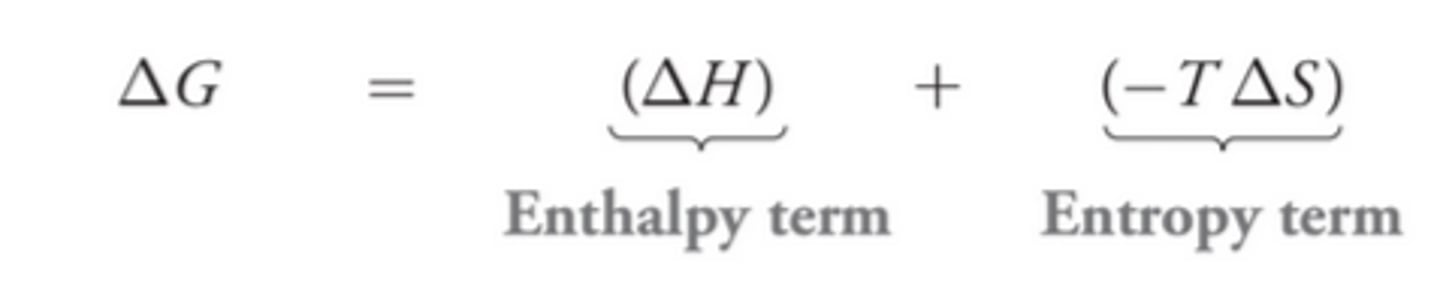

∆G Relation to Addition Reactions

To understand the reason for the temperature dependence of addition reactions, recall that the sign of ∆G determines whether the equilibrium favors reactants or products. ∆G must be negative for the equilibrium to favor products and its sign is dependent on the enthalpy term and the entropy term(shown in image)

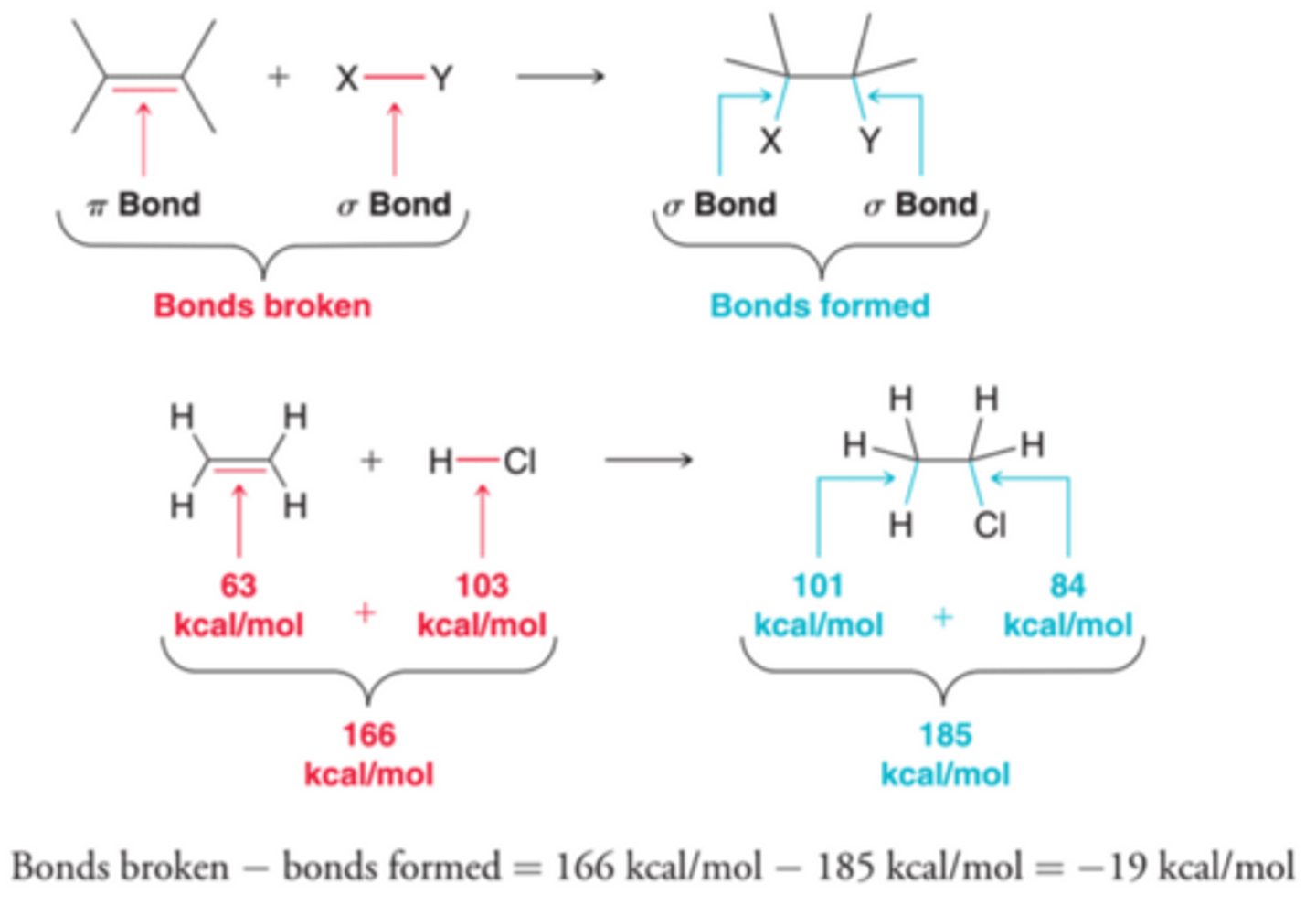

Enthalpy Term(∆H) and Its Relation to Addition Reactions

The dominant factor that contributes to the sign and magnitude of ∆H is bond strength. Notice that in addition reactions, one pi bond and one sigma bond are broken while two sigma bonds are formed(1st example in image). Sigma bonds are stronger than pi bonds, and therefore, the bonds being formed are stronger than the bonds being broken, leading to a negative ∆H and therefore an exothermic reaction, which is generally the case for addition reactions(2nd example in image)

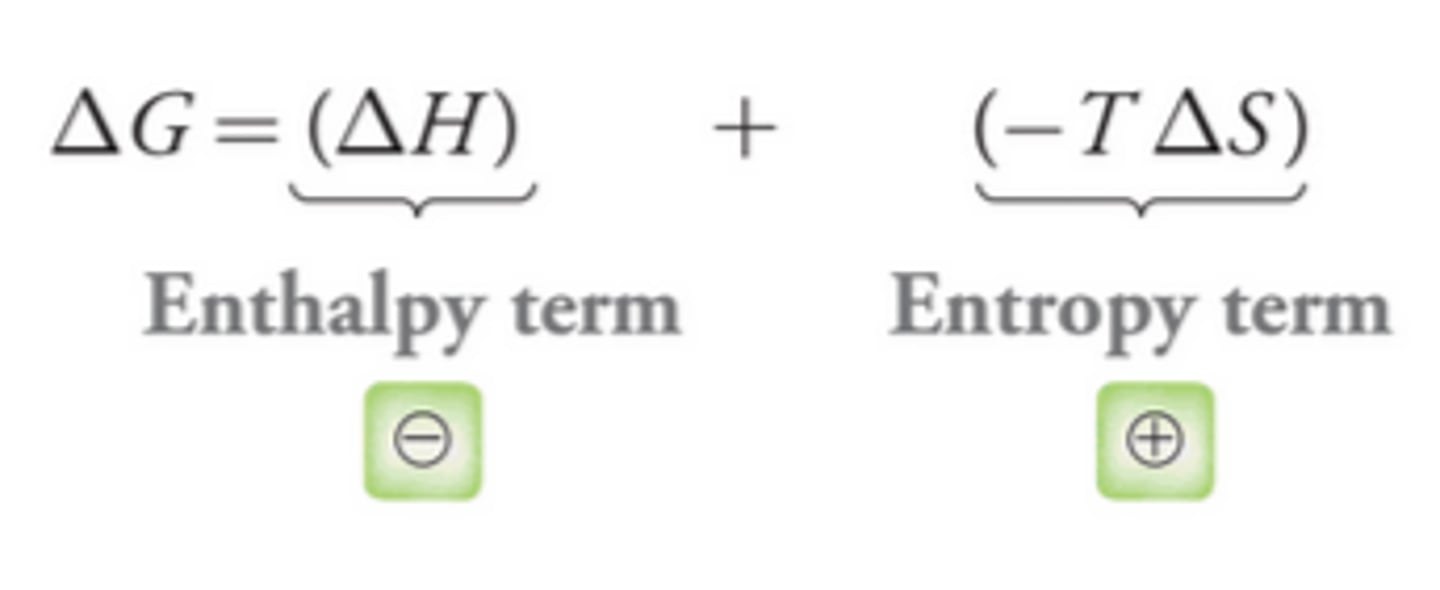

Entropy Term(-T∆S) and its Relation to Addition Reactions

This term will always be positive for an addition reaction because in an addition reaction, two molecules are joining together to product one molecule of products, which represents a decrease in entropy, leading to ∆S having a negative value and the temperature component, T(measured in Kelvin), is always positive. As a result, -T∆S will be positive for addition reactions

Combining Enthalpy and Entropy Terms in Relation to Addition Reactions

The enthalpy term is negative and the entropy term is positive, so the sign of ∆G for an addition reaction will be determined by the competition between these two terms(example in image).

Low Temperature Affect on Addition Reactions

In order for ∆G to be negative, the enthalpy term must be larger than the entropy term. Competition between both terms is temperature dependent in that, at low temperatures, the entropy term is small, allowing the enthalpy term to dominate, giving ∆G a negative value, which means that products are favored over reactants(equilibrium constant K will be greater than 1). In other words, addition reactions are thermodynamically favorable at low temperatures

High Temperature Affect on Addition Reactions

At high temperature, the entropy term will be large and will dominate the enthalpy term, resulting in a positive ∆G, which means that reactant will be favored over products(equilibrium constant K will be less than 1). In other words, the reverse process, elimination, will be thermodynamically favored at high temperature

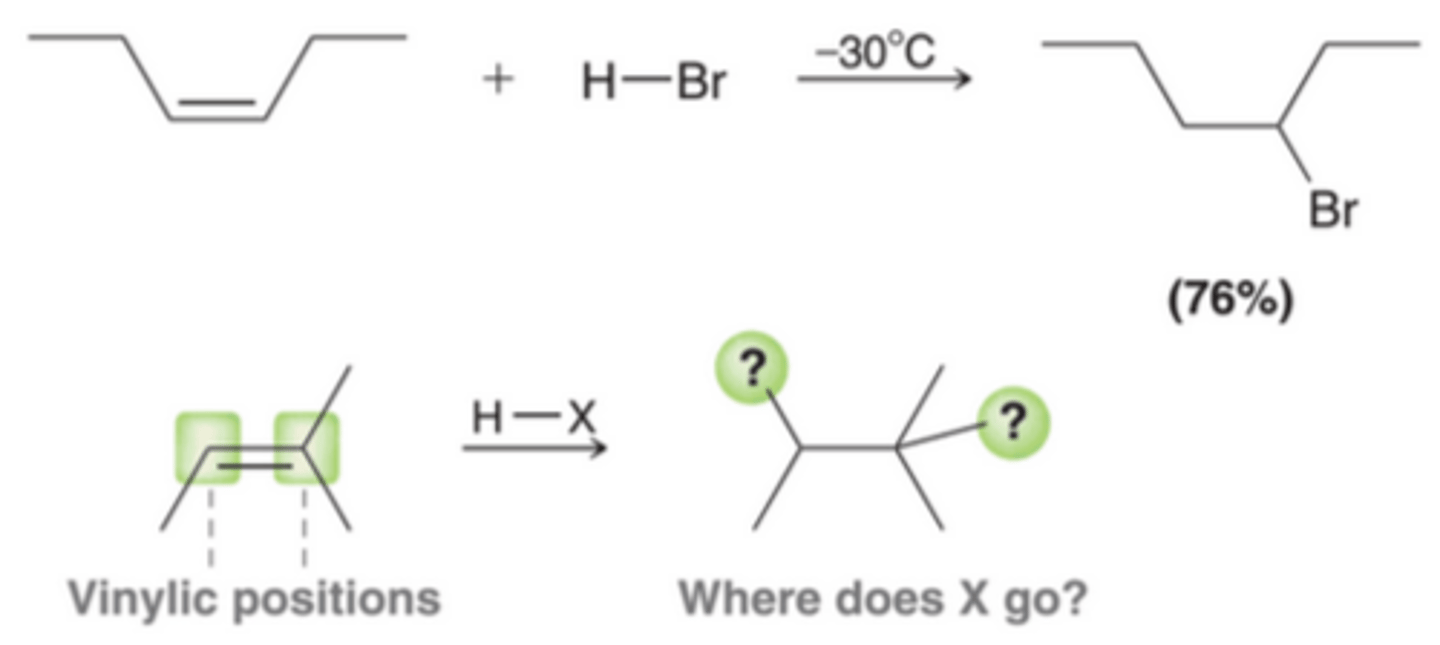

Hydrohalogenation

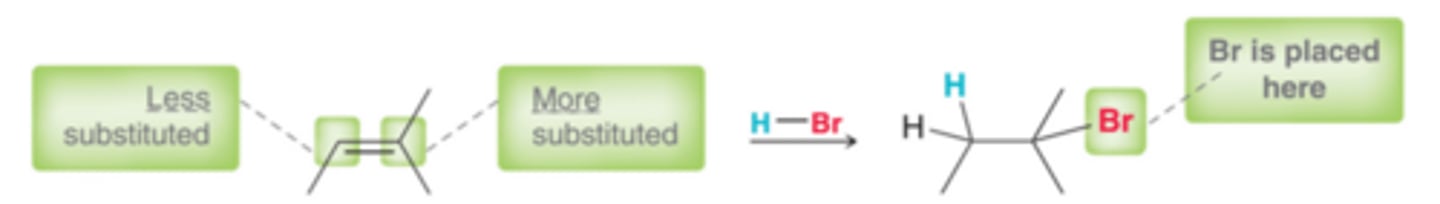

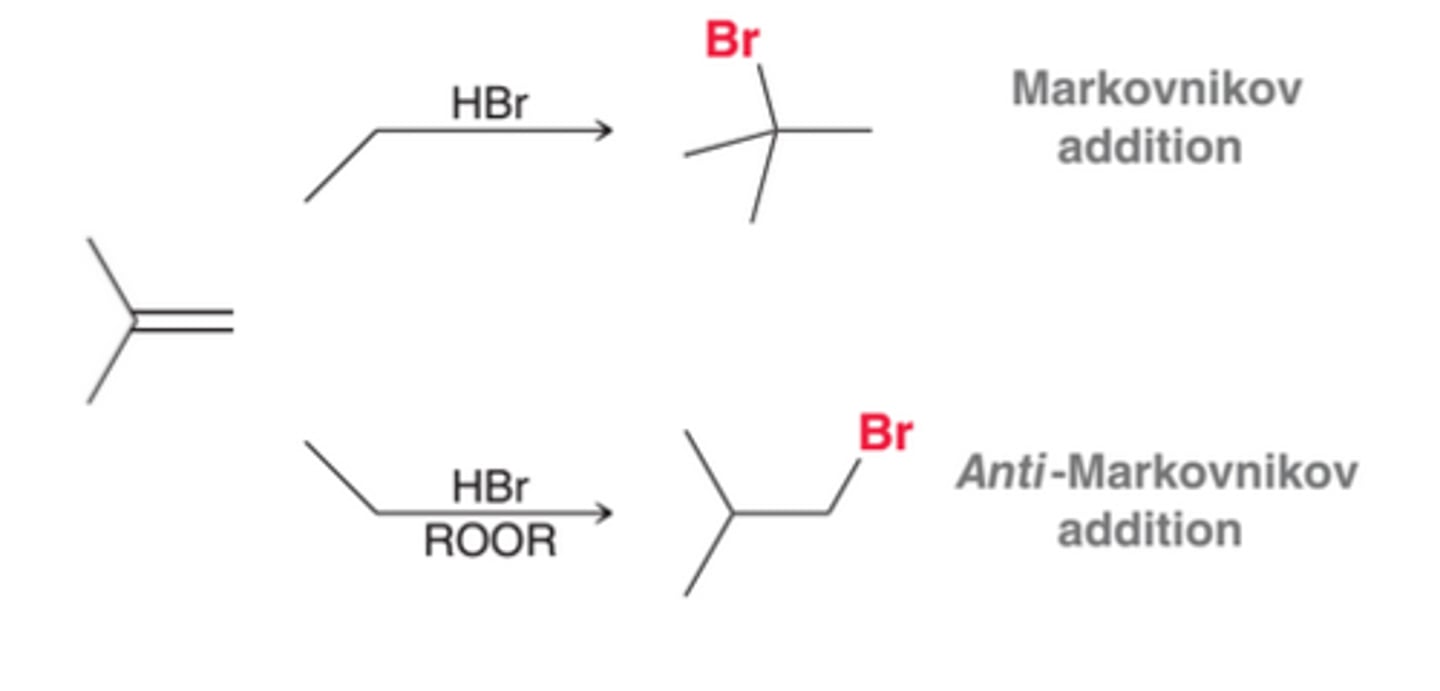

The treatment of alkenes with HX(where X=Cl, Br, or I) results in an addition reaction called hydrohalogentation, in which H and X are added across the pi bond. In 1st process in this image, the alkene is symmetrical. However, in cases where the alkene is unsymmetrical, the ultimate placement of H and X must be considered. In the 2nd process in this image, there are two possible vinylic positions where X can be placed.

Markovnikov Addition

The vinylic position bearing more alkyl groups is more substituted, and that is where the halogen is generally placed. This regiochemical preference, called Markovnikov addition(named after Russian chemist who observed this), is also observed for addition reactions involving HCl and HI

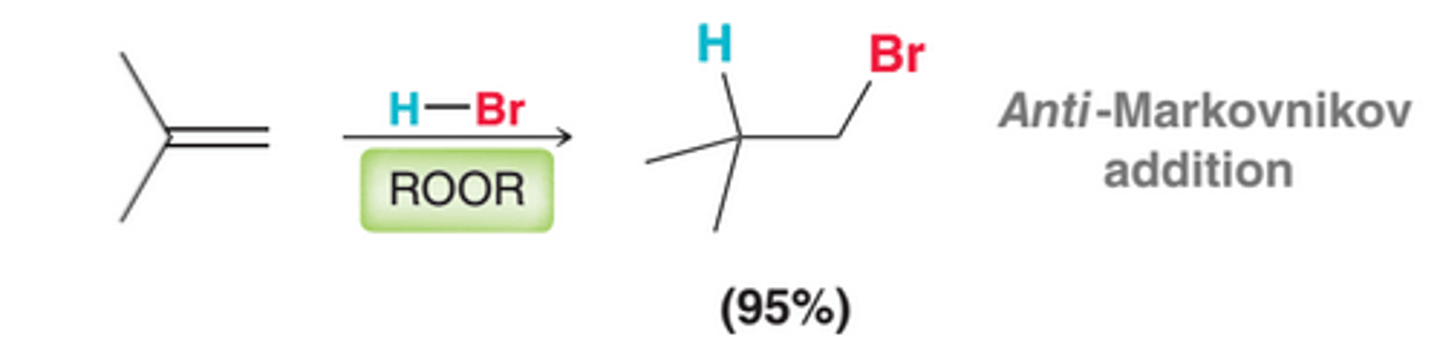

anti-Markovnikov Addition

Peroxides(ROOR), even in trace amounts, cause HBr to add across an alkene where the bromine atom would be installed at the less substituted carbon, in an anti-Markovnikov addition

Regioselectivity of Hydrohalogenation

The regiochemical outcome of HBr addition can be controlled by choosing whether or not to use peroxides

A Mechanism for Hydrohalogenation

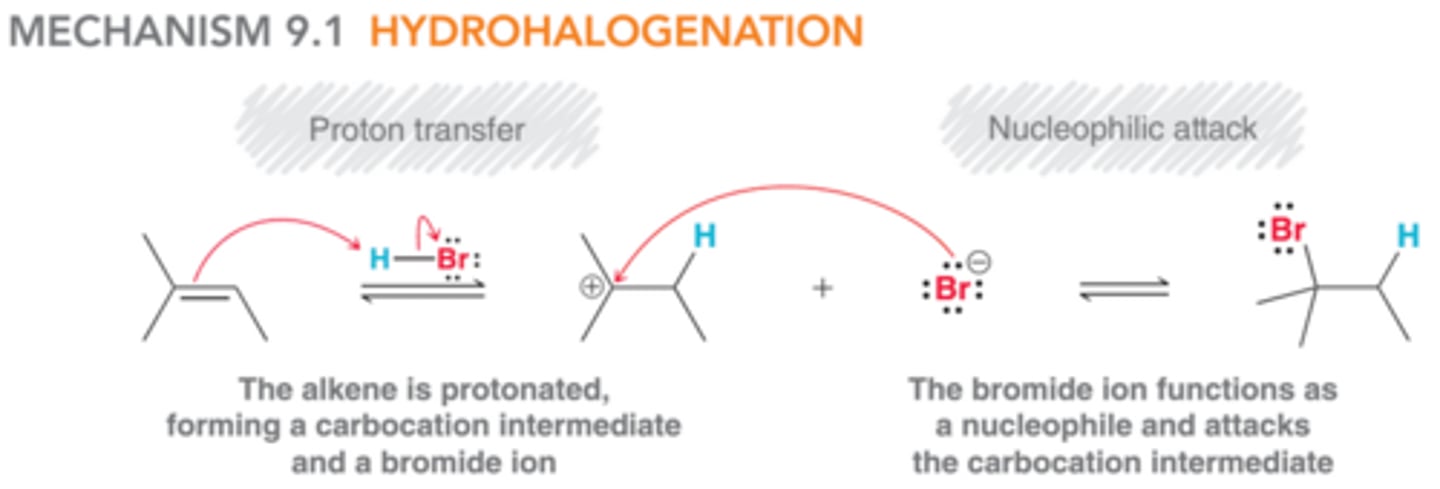

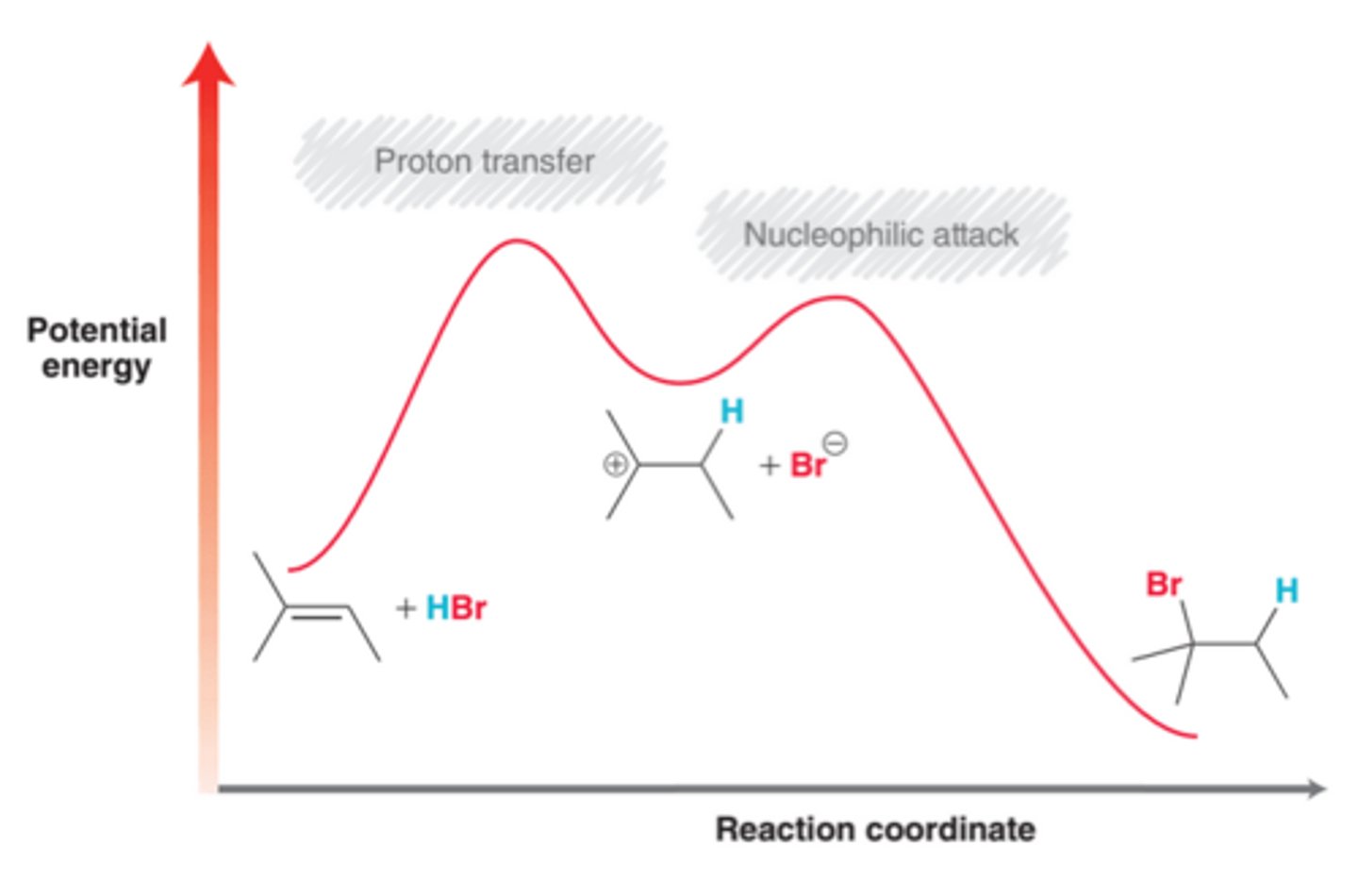

The mechanism in this image accounts for the Markovnikov addition of HX to alkenes. In the first step, the pi bond of the alkene is protonated, generating a carbocation intermediate. In the second step, this intermediate is attacked by a bromide ion.

Energy Diagram for Hydrohalogenation

The observed regioselectivity for this process can be attributed to the first step of the mechanism(proton transfer), which is the rate-determining step because it exhibits a higher transition energy than the second step of the mechanism

The Regiochemical Possibilities of Hydrohalogenation

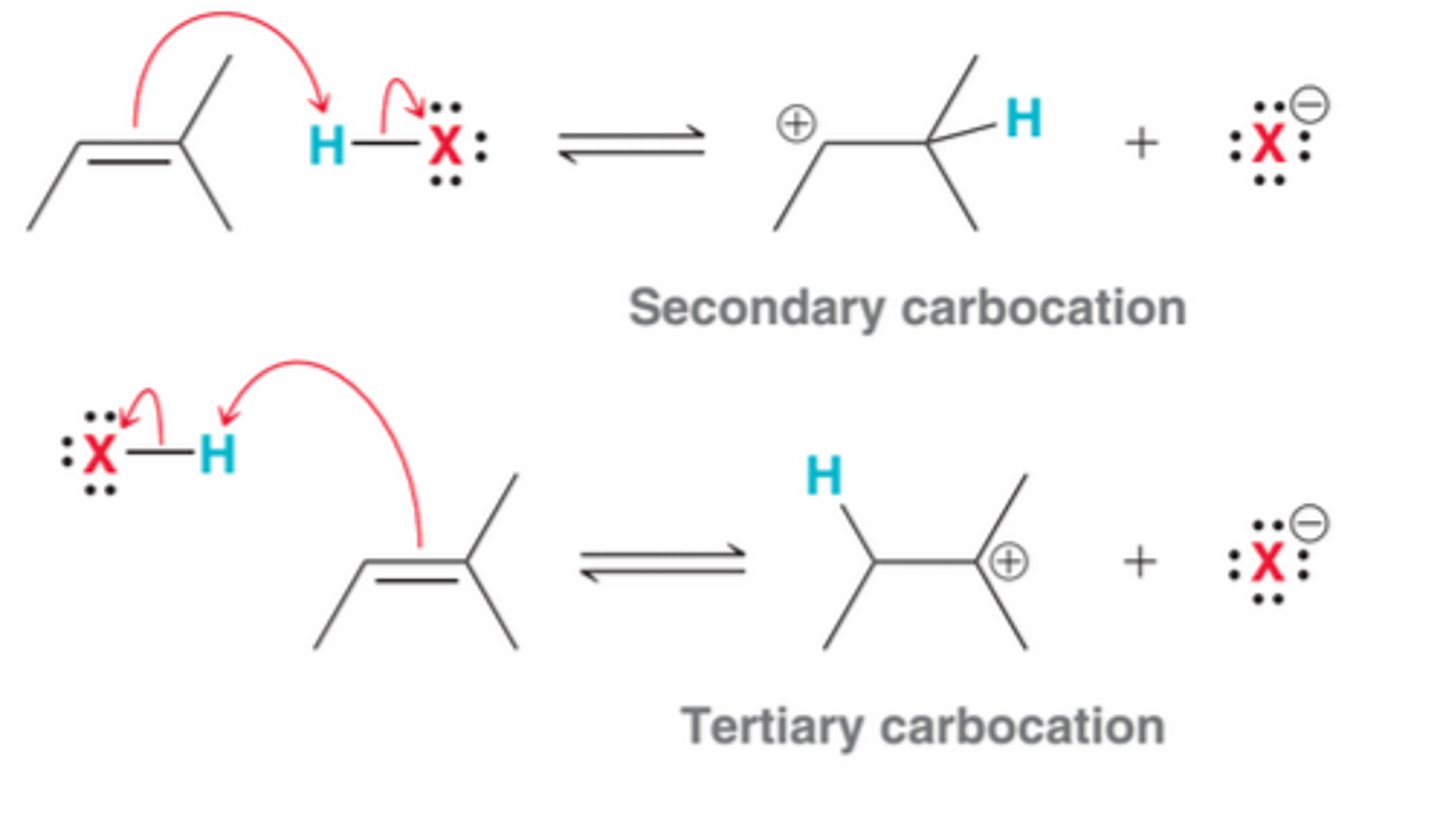

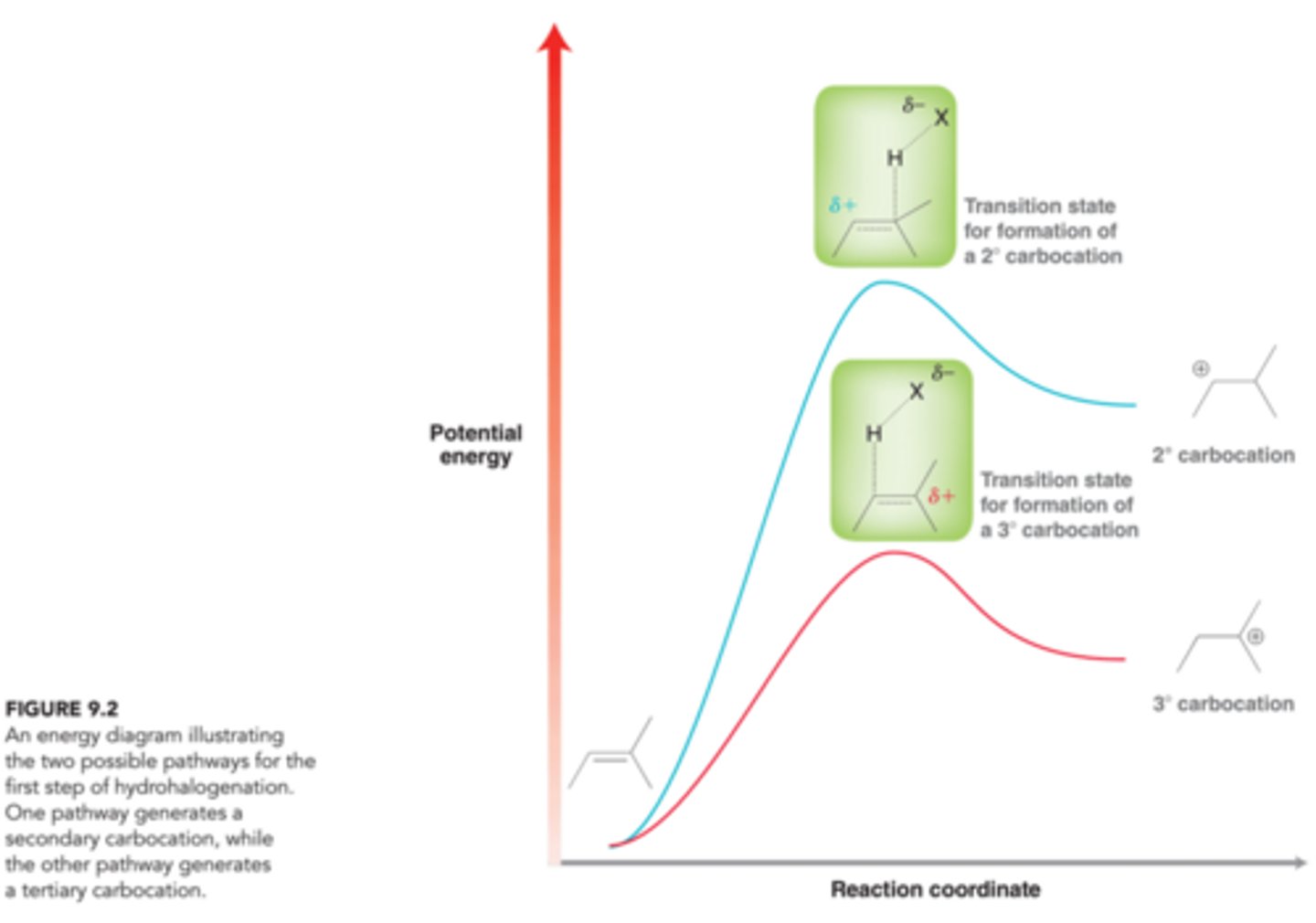

In theory, protonation can occur with either of two regiochemical possibilities. It can either occur to form the less substituted, secondary carbocation, seen as 1st process in image, or occur to form the more substituted, tertiary carbocation, seen as 2nd process in image. Tertiary carbocation are more stable than secondary carbocations, due to hyperconjugation

Energy Diagram Comparing Two Possible Pathway for the First Step of HX Addition

As seen in image, the energy barrier for the formation of the tertiary carbocations will be smaller than the energy barrier for formation of the secondary carbocation, and as a result, the reaction will proceed more rapidly via the more stable carbocation intermediate.

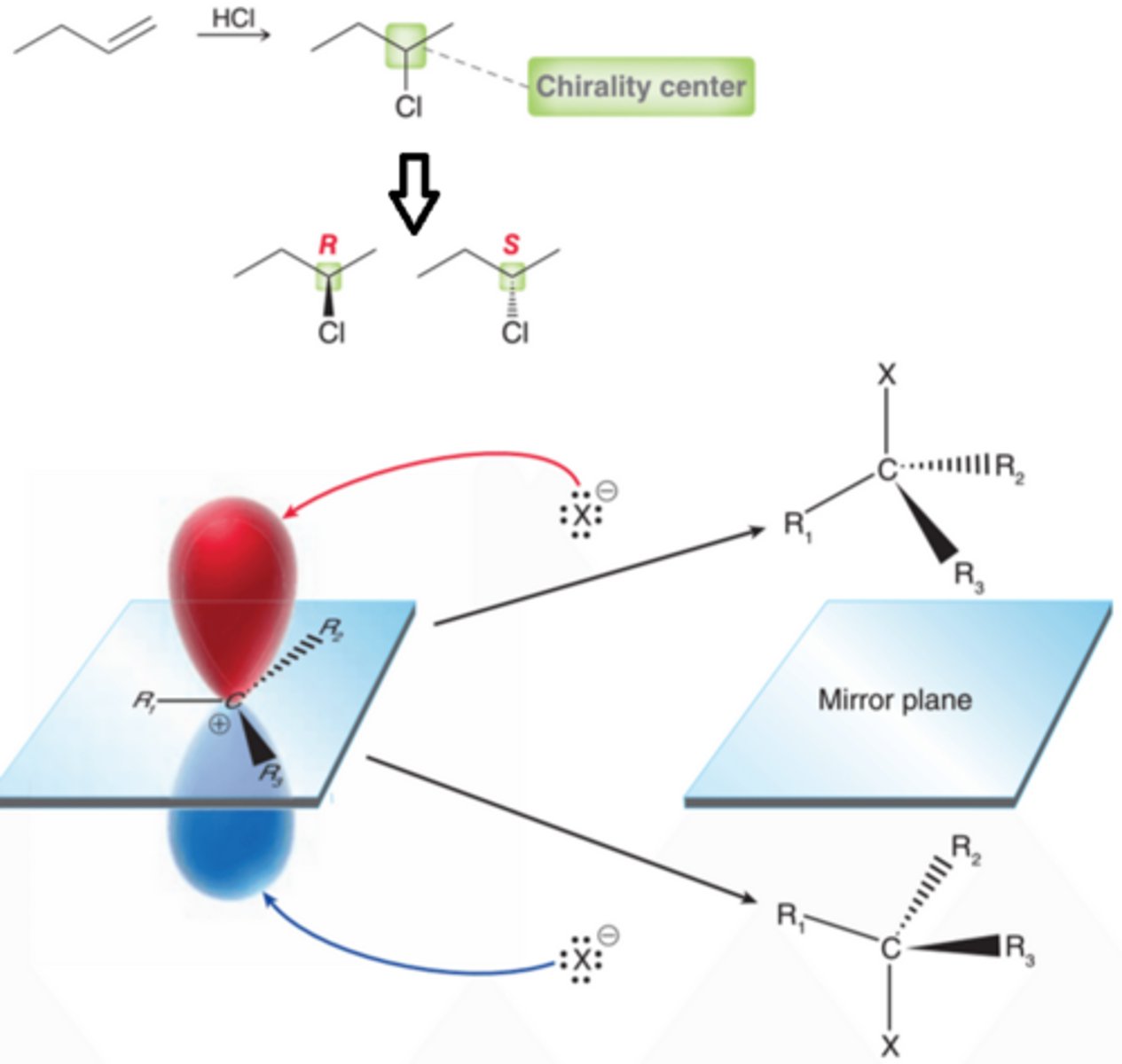

Stereochemistry for Hydrohalogenation

In many cases, hydrohalogenation involves the formation of a chirality center(1st example in image). In the reaction in the 1st example in this image, one new chirality center is formed. Therefore, two possible products are expected representing a pair of enantiomers(2nd example in image). The two enantiomers are produced in equal amounts, forming a racemic mixture. A carbocation is trigonal planr, with an empty p orbital orthagonal to the plane, so the empty p orbital is subject to attack by a nucleophile on either side with equal likelihood, producing both enantiomers in equal amounts(3rd example in image).

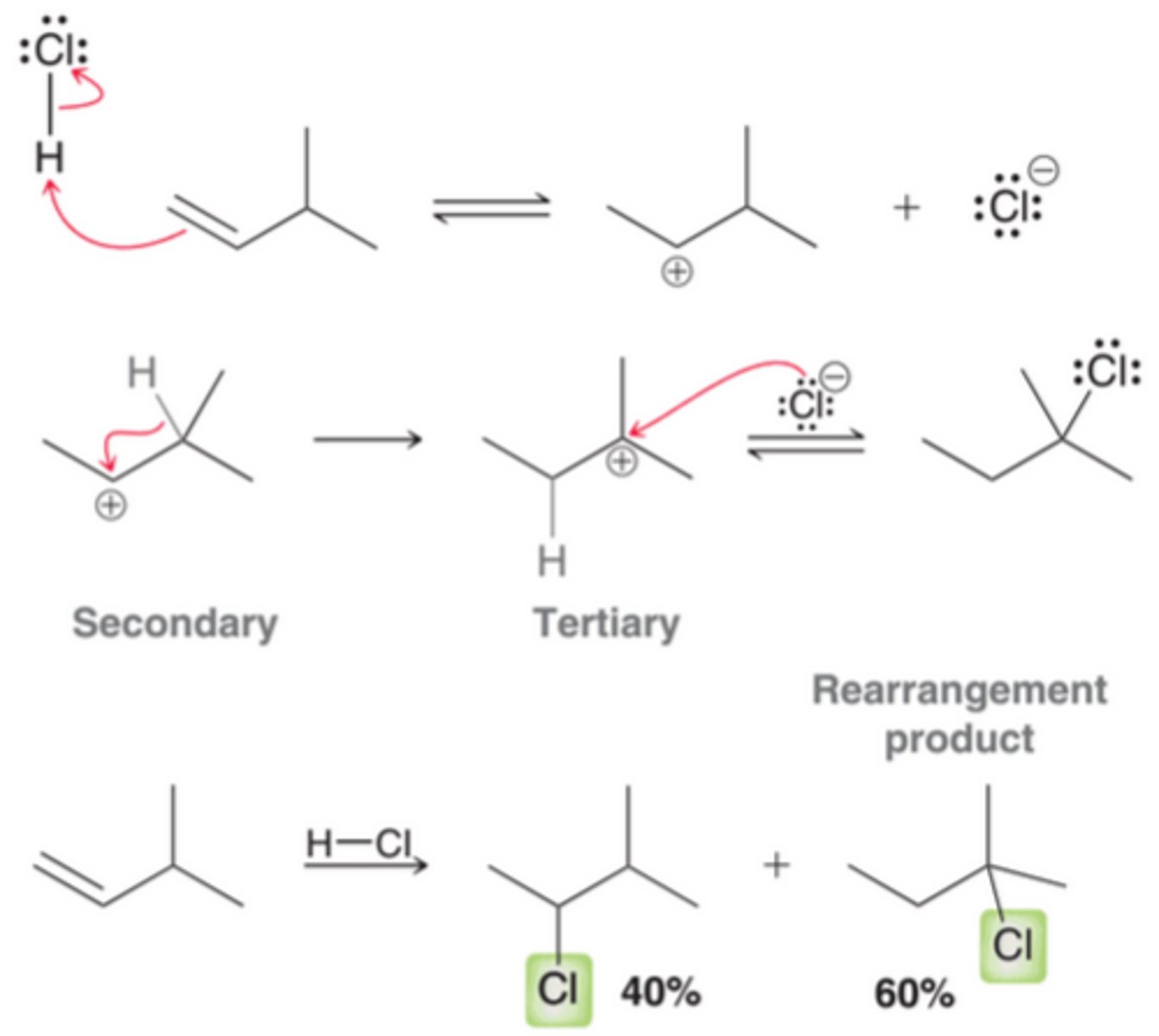

Hydrohalogenation with Carbocation Rearrangement

Because the mechanism for HX addition involves formation of an intermediate carbocation, HX additions are subject to carbocation rearrangements. In cases where rearrangements are possible, HX additions produce a mixture of products, including those resulting from a carbocation rearrangement as well as those formed without rearrangement, which happens when the nucleophile captures the carbocation before rearrangement has a chance to occur(3rd example).

Hydration

Adding water(H and OH) across a double bond

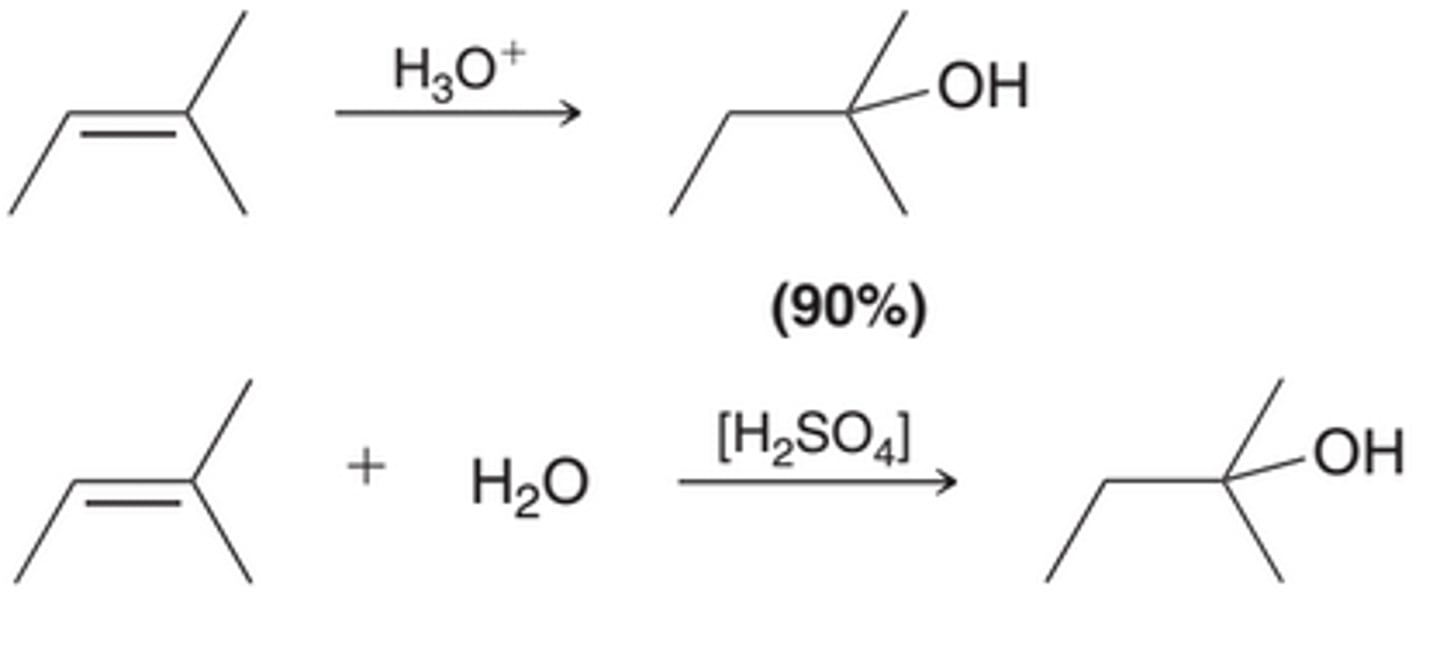

Acid-Catalyzed Hydration

Addition of water across a double bond in the presence of an acid. For most simply alkenes, this reaction proceeds via a Markovnikov addition. The net result is an addition of H and OH across the pi bond, with the OH group positioned at the more substituted carbon(1st example in image). The reagent, H3O^+, represents the presence of both water(H2O) and an acid source, such as sulfuric acid(2nd example in image). The brackets in the 2nd example in this image indicate that the proton source is not consumed in the reaction. It is a catalyst, and, therefore, this reaction is said to be an acid-catalyzed hydration

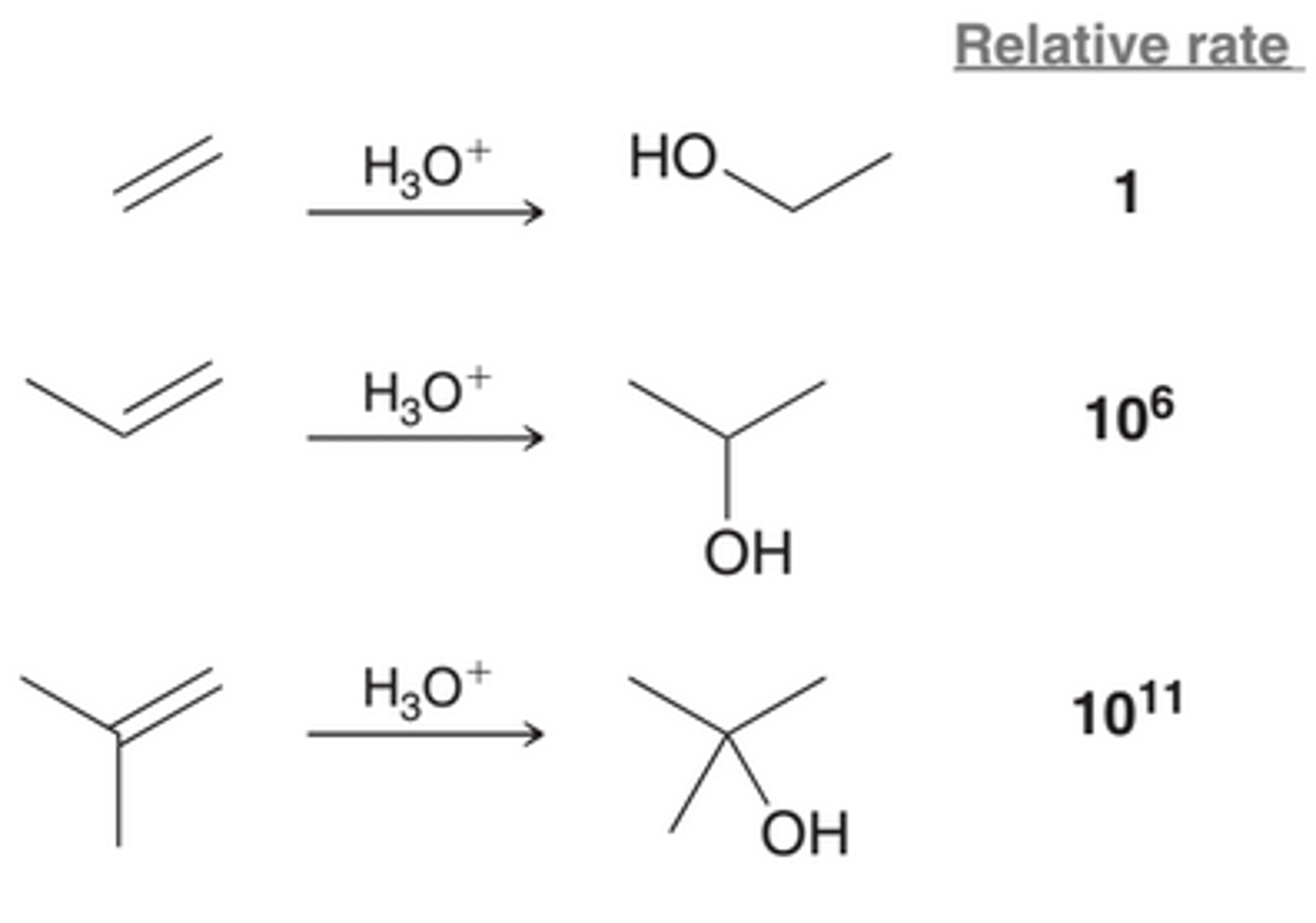

Rate of an Acid-Catalyzed Hydration

The rate of an acid-catalyzed hydration is very much dependent on the structure of the starting alkene with the reaction rate increasing by many order of magnitude with each additional alkyl group. The OH group is placed at the more substituted position

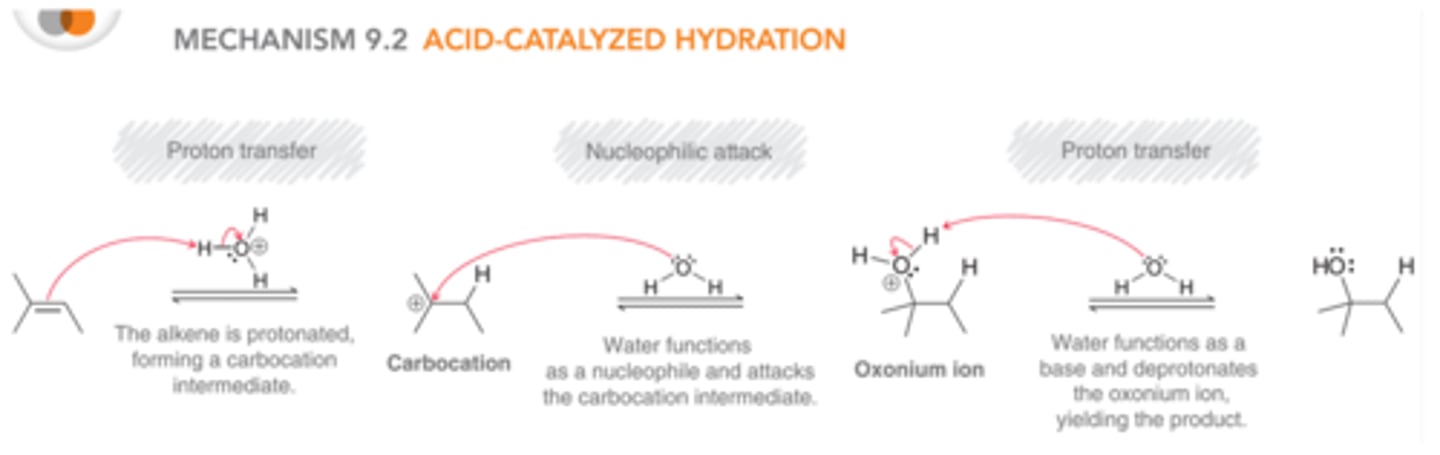

Mechanism for Acid-Catalyzed Hydration

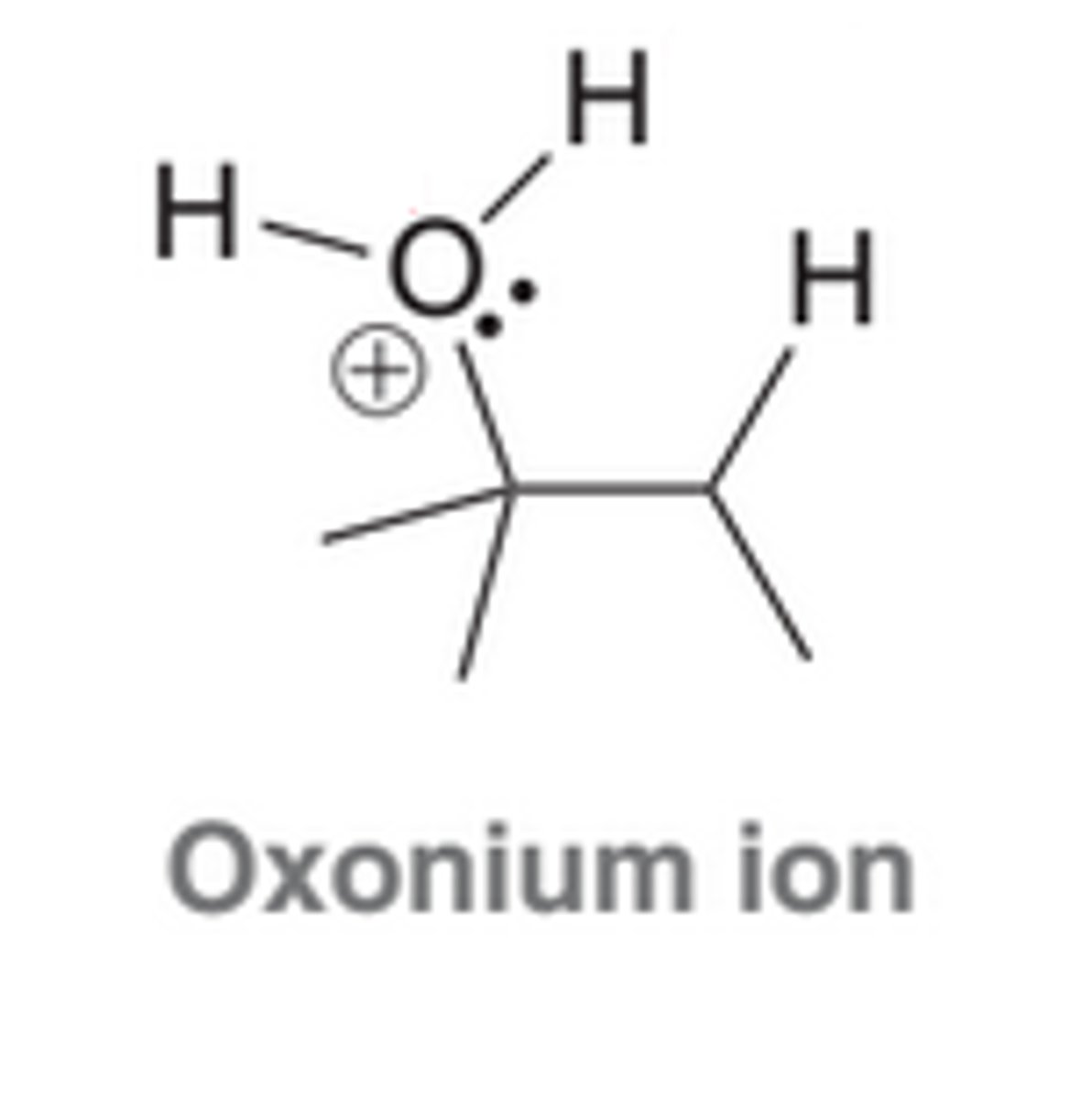

The alkene is first protonated to generate a carbocation intermediate, which is then attacked by a nucleophile, which is identical to hydrohalogenation. However, in this case the attacking nucleophile is neutral(H2O) rather than an anion(X^-), and therefore, a positively charged intermediate is generated. This positively charged intermediate is called an oxonium ion, and in order to remove this charge and form an electrically neutral product, the mechanism must conclude with a proton transfer

Oxonium Ion

A molecule that exhibits an oxygen atom with a positive charge

Based used for Deprotonation in an Acid-Catalyzed Hydration

Notice that the base used to deprotonate the oxonium ion in the last step is H2O rather than a hydroxide ion(HO^-) because in acidic conditions, the concentration of hydroxide ions is extremely low, but the concentration of H2O is quite large

Le Chatelier's Principle

States that a system at equilibrium will adjust in order to minimize any stress placed on the system

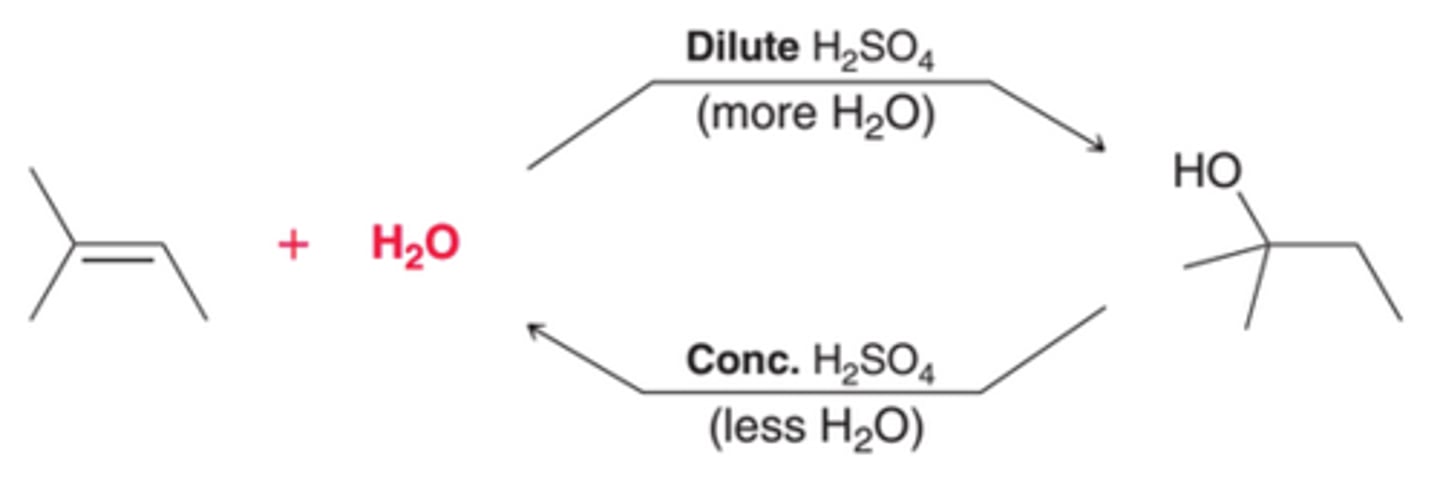

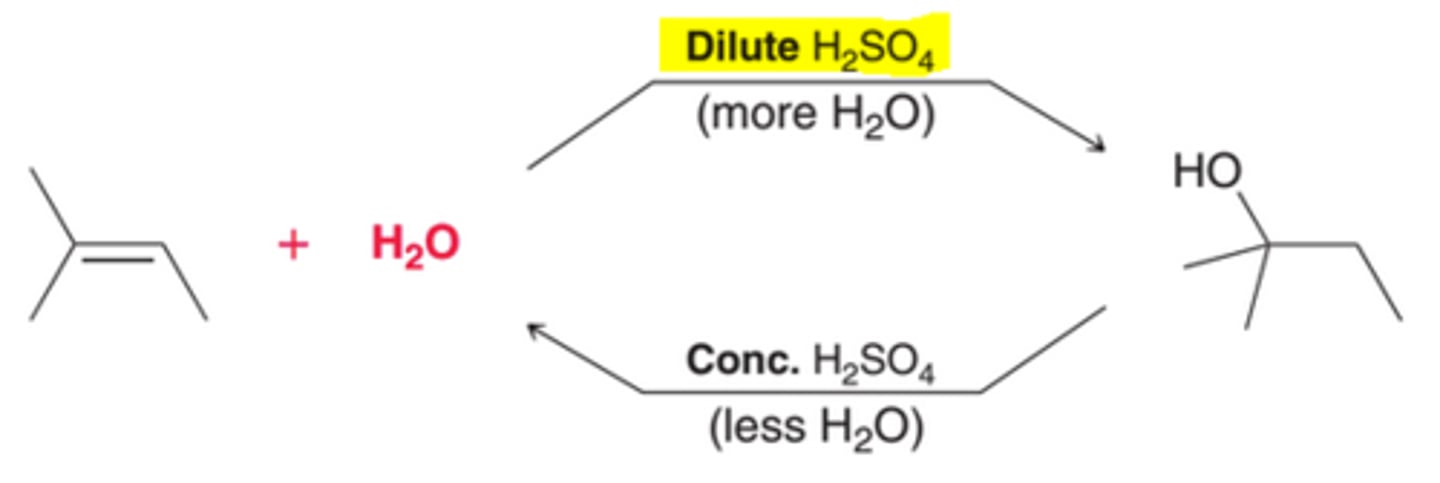

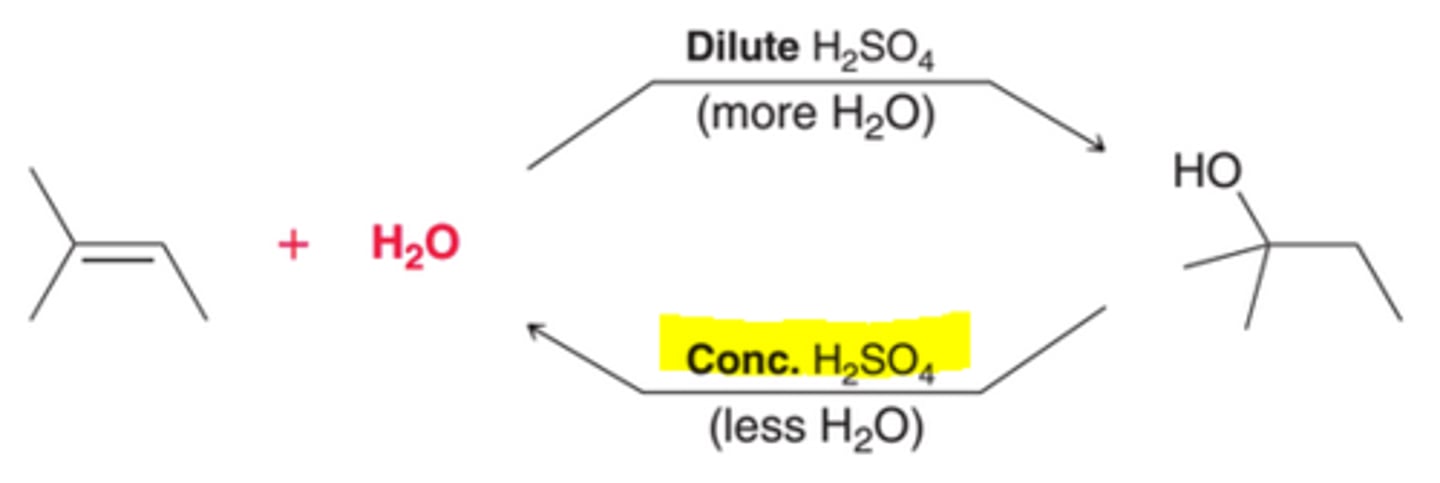

Controlling the Position of Equilibrium of an Acid-Catalyzed Hydration

By controlling the amount of water present(using either concentrated acid or dilute acid), one side of equilibrium can be favored over the other.

A Dilute Acid's Affect on Equilibrium of Acid-Catalyzed Hydration

The introduction of more water will cause the position of equilibrium to move in such a way that more of the alcohol is produced. Therefore, dilute acid, which is mostly water, is used to convert an alkene into an alcohol.

A Concentrated Acid's Affect on Equilibrium of Acid-Catalyzed Hydration

Removing water from the system would cause the equilibrium to favor the alkene. Therefore, concentrated acid, which is very little water, is used to favor formation of the alkene.

A Distillation Process's Affect on Equilibrium of Acid-Catalyzed Hydration

Water can be removed from the system via a distillation process, which would favor the alkene

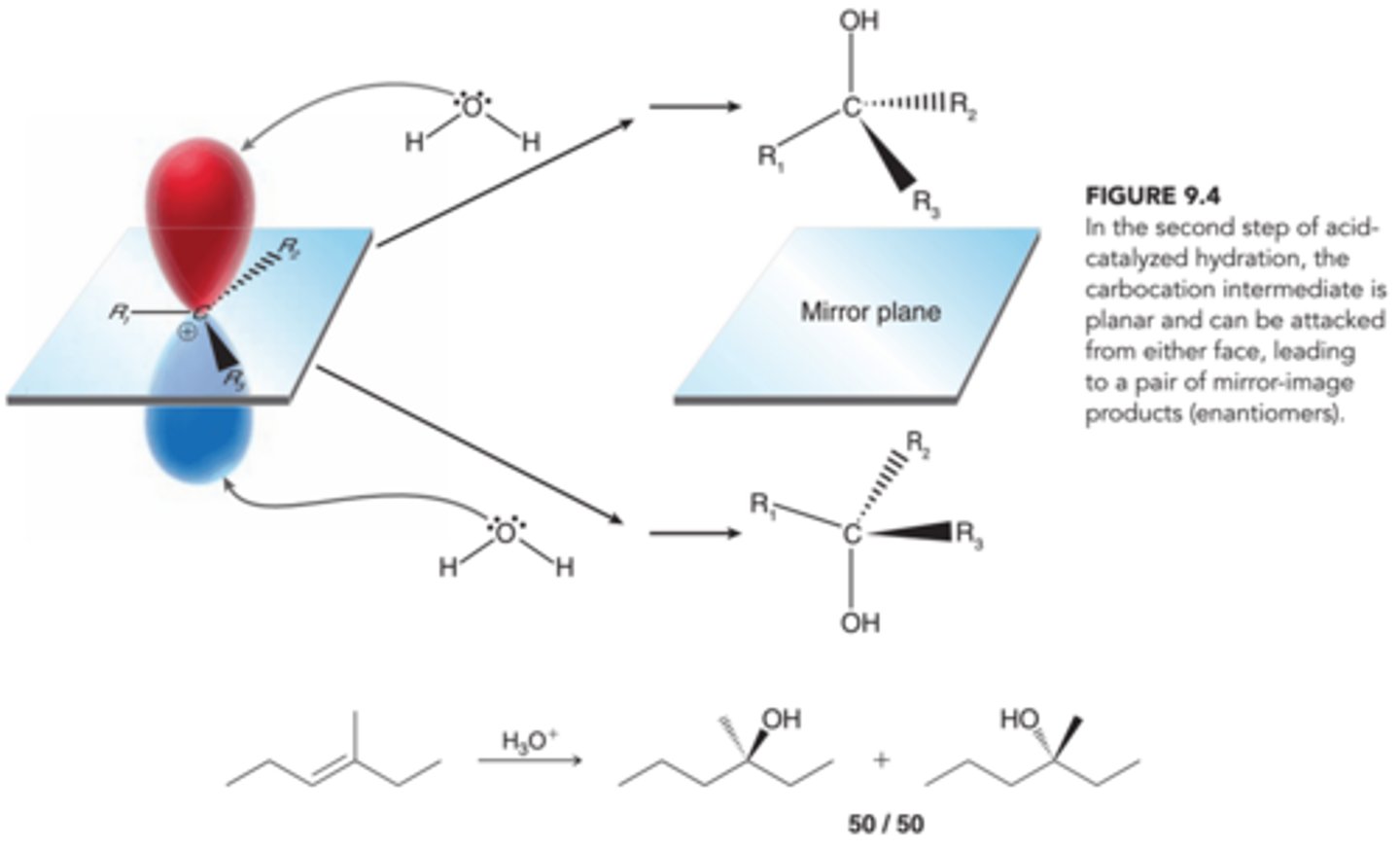

Stereochemistry of Acid-Catalyzed Hydration

The stereochemical outcome of acid-catalyzed hydration is similar to the stereochemical outcome of hydrohalogenation. The intermediate carbocation can be attacked from either side with equal likelihood(1st example in image). Therefore, when a new chirality center is generated, a racemic mixture of enantiomers is expected

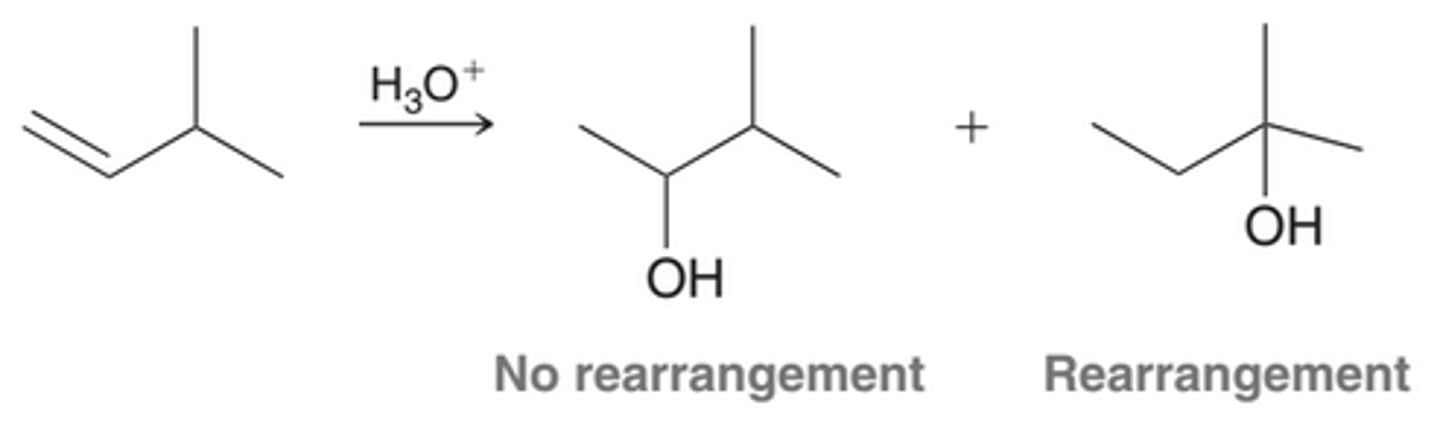

Inefficiency of Acid-Catalyzed Hydration when Carbocation Rearrangement is Required

The utility of the Acid-Catalyzed Hydration process is somewhat diminished by the fact that carbocation rearrangement can produce a mixture of products. In cases where protonation of the alkene ultimately leads to carbocation rearrangements, acid-catalyzed hydration is an inefficient method for adding water across the alkene

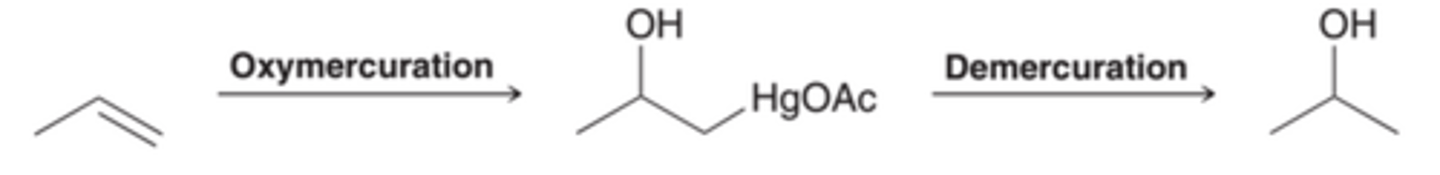

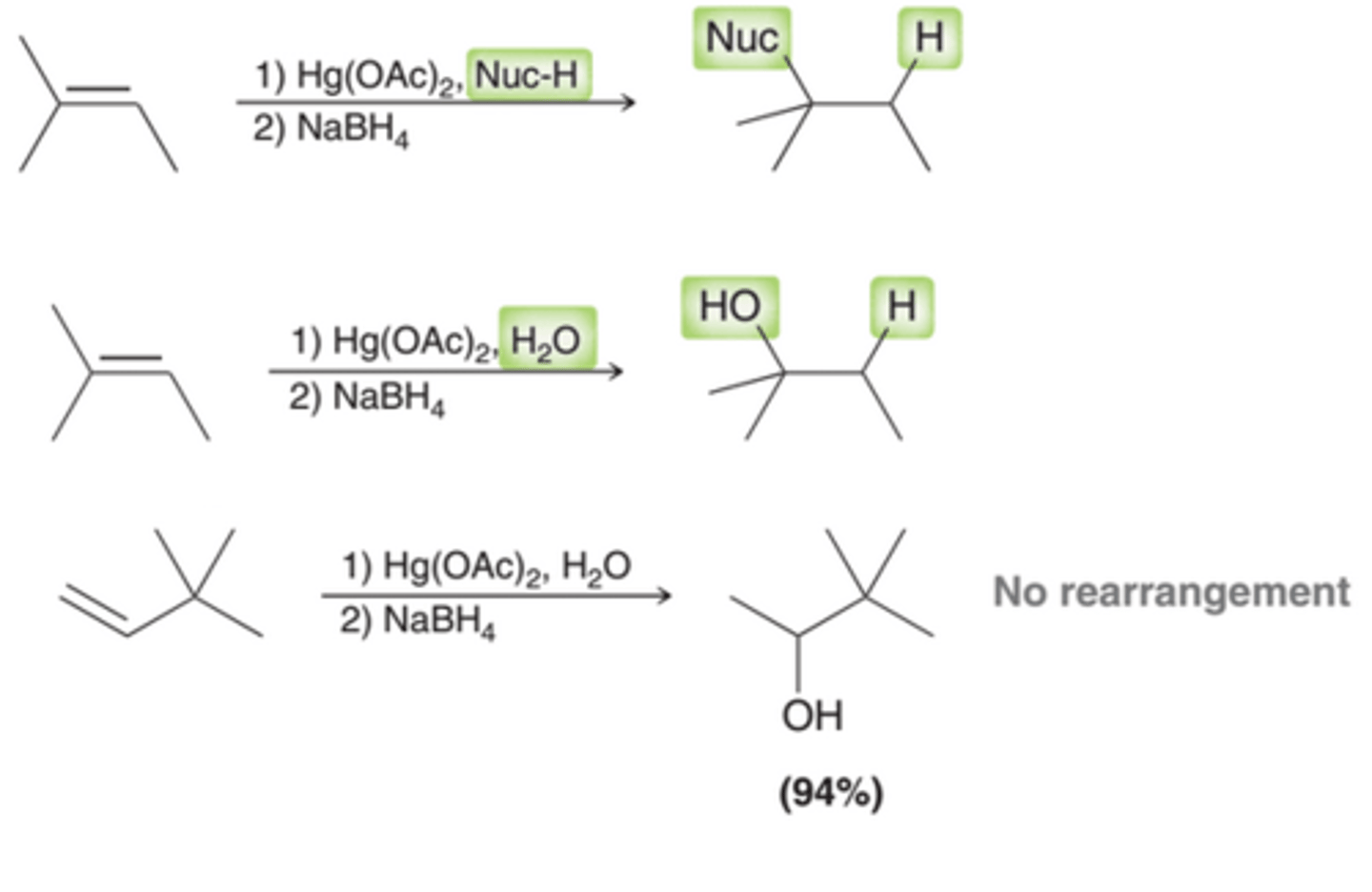

Oxymercuration-Demercuration

One of the oldest and perhaps best known methods that can achieve a Markovnikov addition of water across an alkene without carbocation rearrangements.

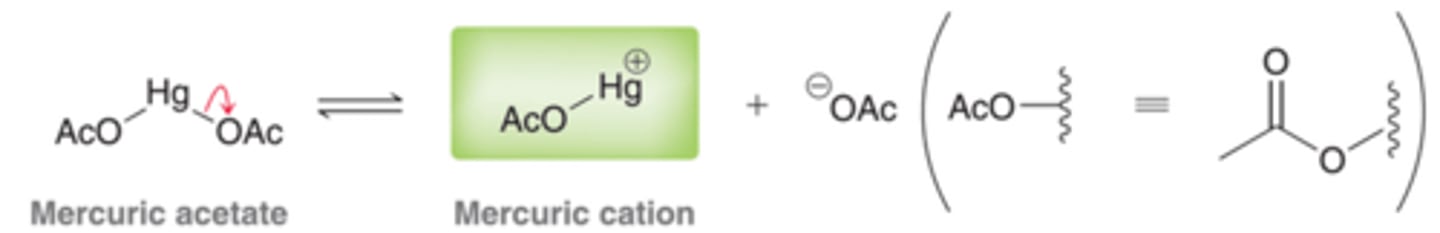

The Reagents Employed in Oxymercuration-Demercuration

To understand the Oxymercuration-Demercuration process, we must explore the reagents employed. The process begins when mercuric acetate, Hg(OAc)2, dissociated to form a mercuric cation, as shown in this image.

Mercuric Cation

The mercuric cation is a powerful electrophile and is subject to attack by a nucleophile, such as the pi bond of an alkene. When a pi bond attacks a mercuric cation, the nature of the resulting intermediate is quire different from the nature of the intermediate formed when a pi bond is simply protonated.

Comparing When a Pi Bond Attacks a Mercuric Cation and When a Pi Bond is Protonated

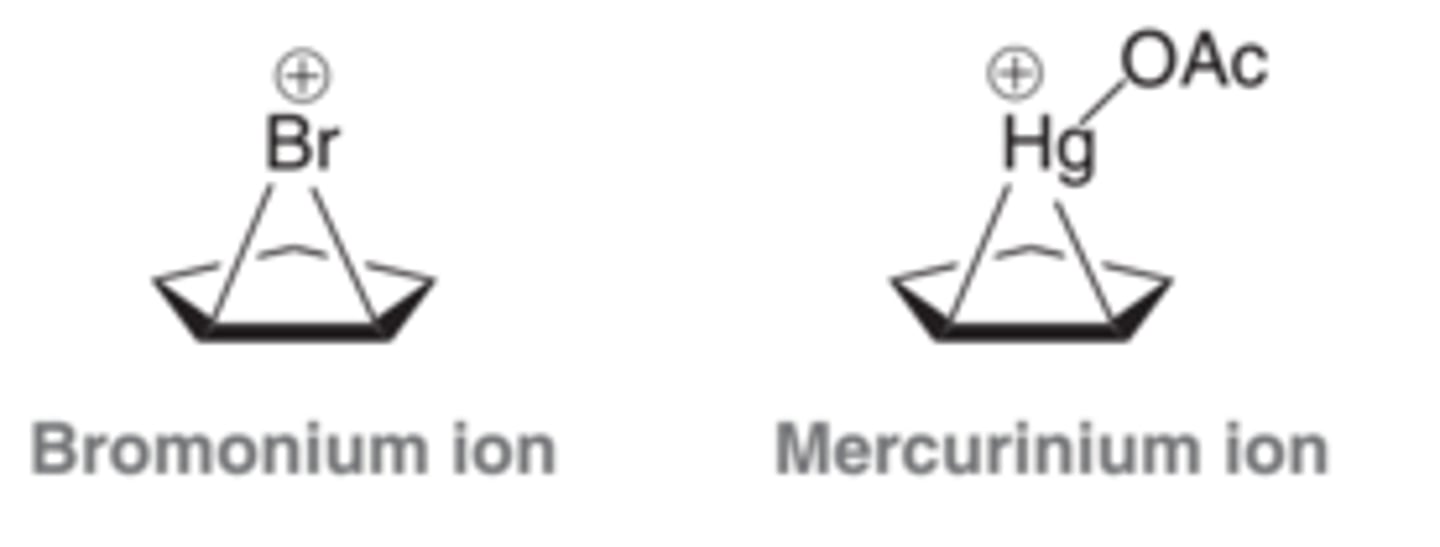

When a pi bond is protonated, the intermediate formed is simply a carbocation. In contrast, when a pi bond attacks a mercuric cation, the resulting intermediate cannot be considered as a carbocation, because the mercury atom has electrons that can interact with the nearby positive charge to form a bridge. This intermediate is called a mercurinium ion.

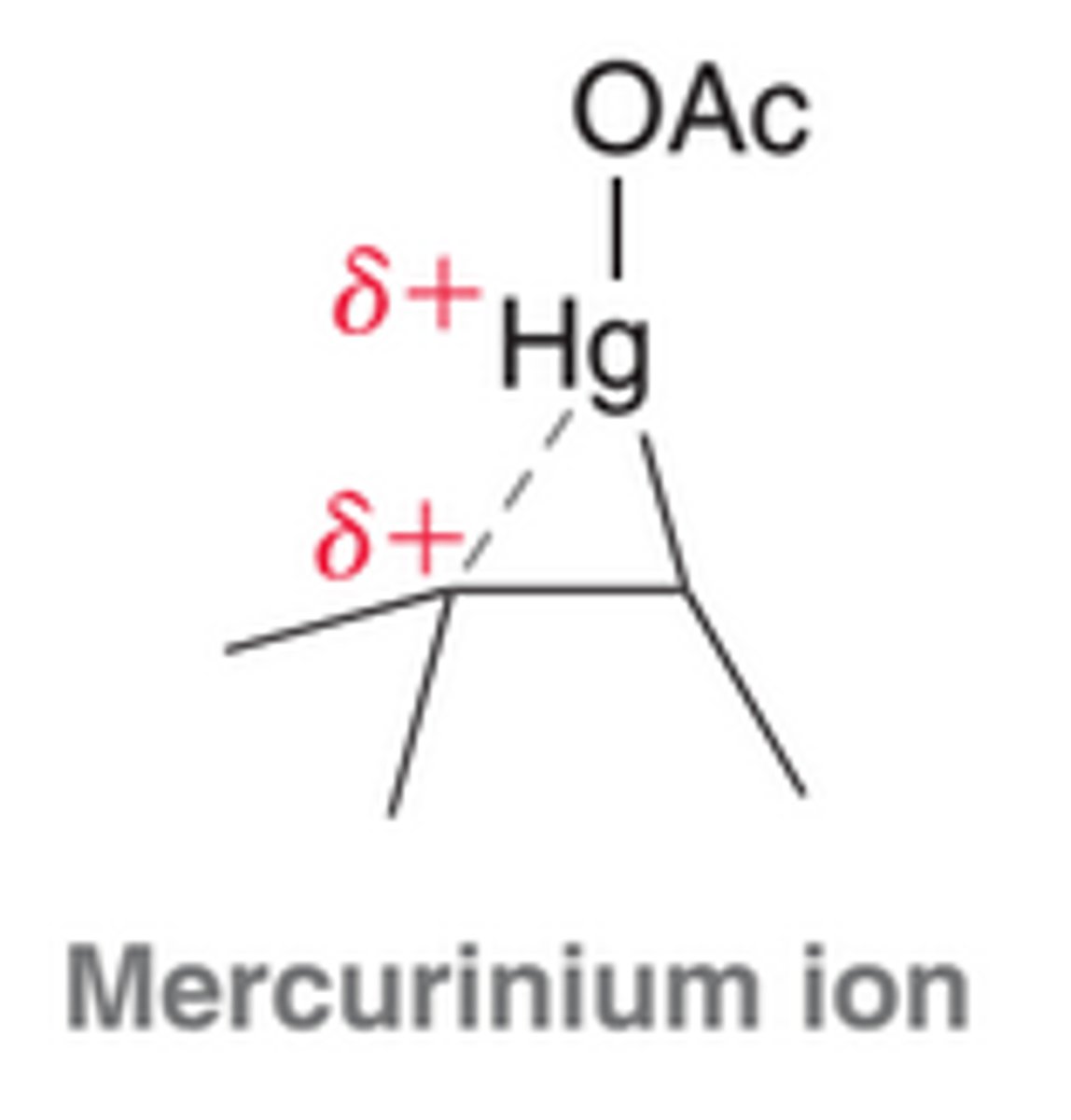

Mercurinium Ion

This intermediate is more adequately described as a hybrid of two resonance structures than as a carbocation. This ion has some of the character of a carbocation, but it also has some of the character of a bridged, three-membered ring.

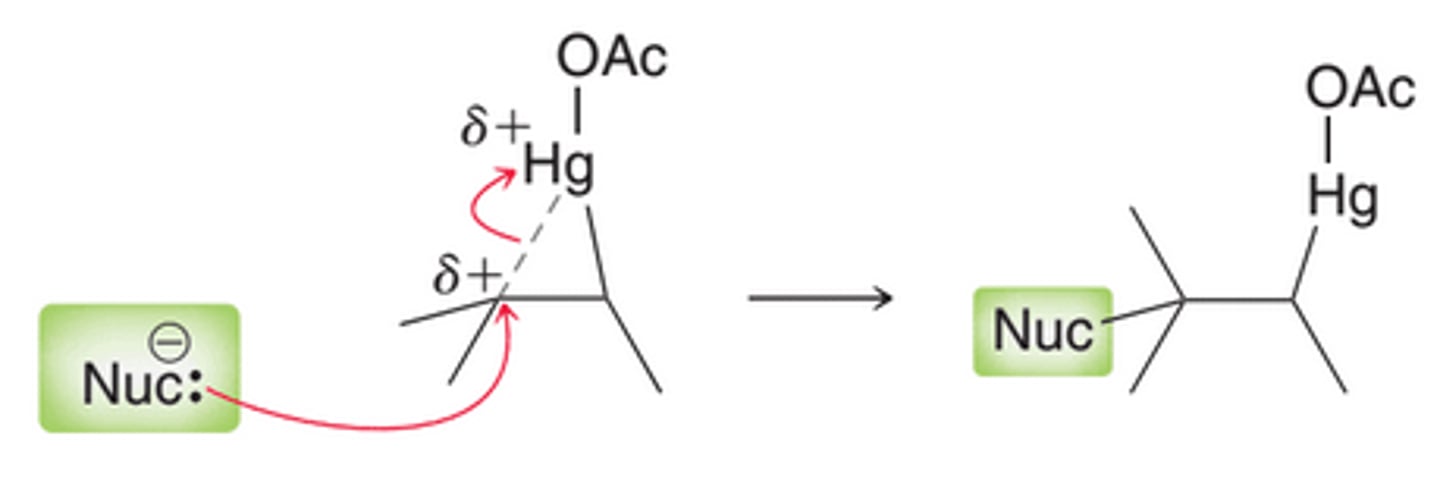

Nucleophilic Attack of the Mercurinium Ion

The more substituted carbon atom bears a partial positive charge(+δ), rather than a full positive charge. As a result, this intermediate will not readily undergo carbocation rearrangement, but it is still subject to attack by a nucleophile. Notice in image that the attack takes place at the more substituted position, ultimately leading to Markovnikov addition

Demercuration

After the attack of the nucleophile, the mercury can be removed through a process called demercuration, which can be accomplished with sodium borohydride. There is much evidence that demurcuration occurs via a radical process

Net Result of Oxymercuration-Demercuration

The net result is the addition of H and a nucleophile across an alkene(1st example in image). Many nucleophiles can be used, including water(2nd example in image). This reaction sequence provides for a two-step process that enables the hydration of an alkene with-out carbocation rearrangments(3rd example in image)

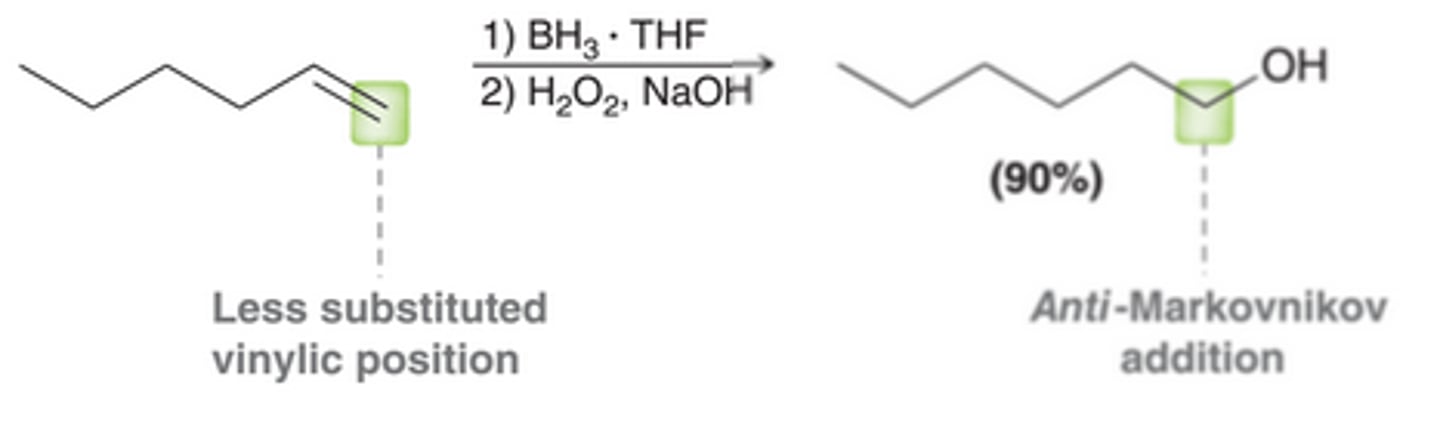

Hydroboration-Oxidation

A method for achieving an anti-Markovnikov addition of water across a pi bond. Places the OH group at the less substituted carbon

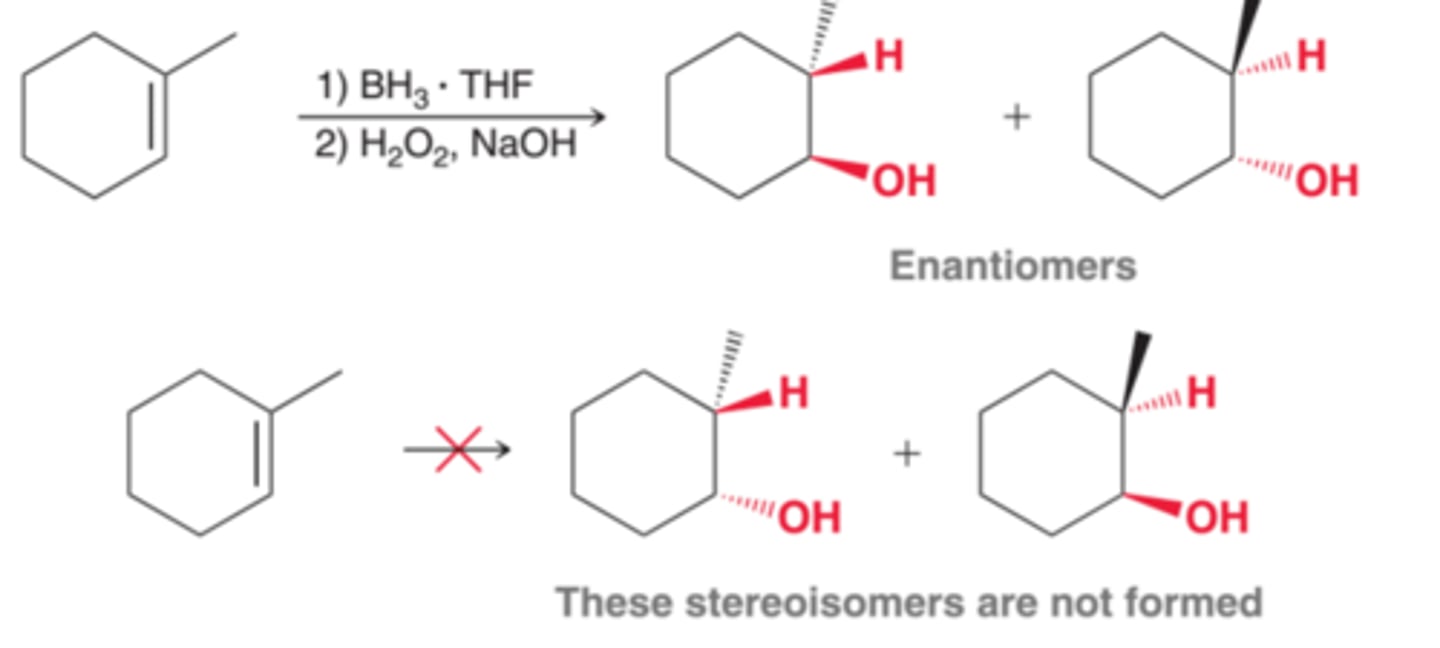

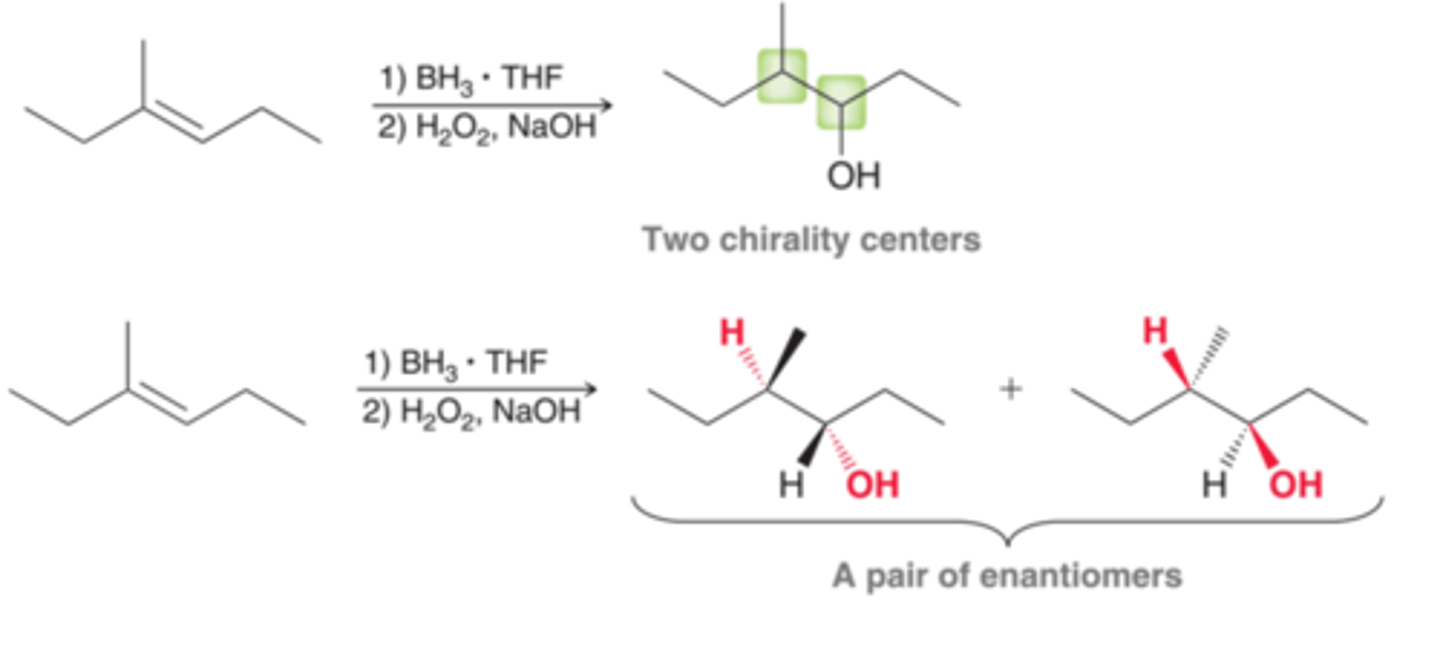

Stereospecifity of Hydroboration-Oxidation and syn Addition

When two new chirality centers are formed, the addition of water(H and OH) is observed to occur in a way that places the H and OH on the same face of the pi bond(1st example in image). This mode of addition is called syn addition. This reaction is said to be stereospecific because only two of the four possible stereosisomers are formed. That is, it does not produce the two stereoisomers that would result from adding H and OH to the opposite side of the pi bond(2nd example in image)

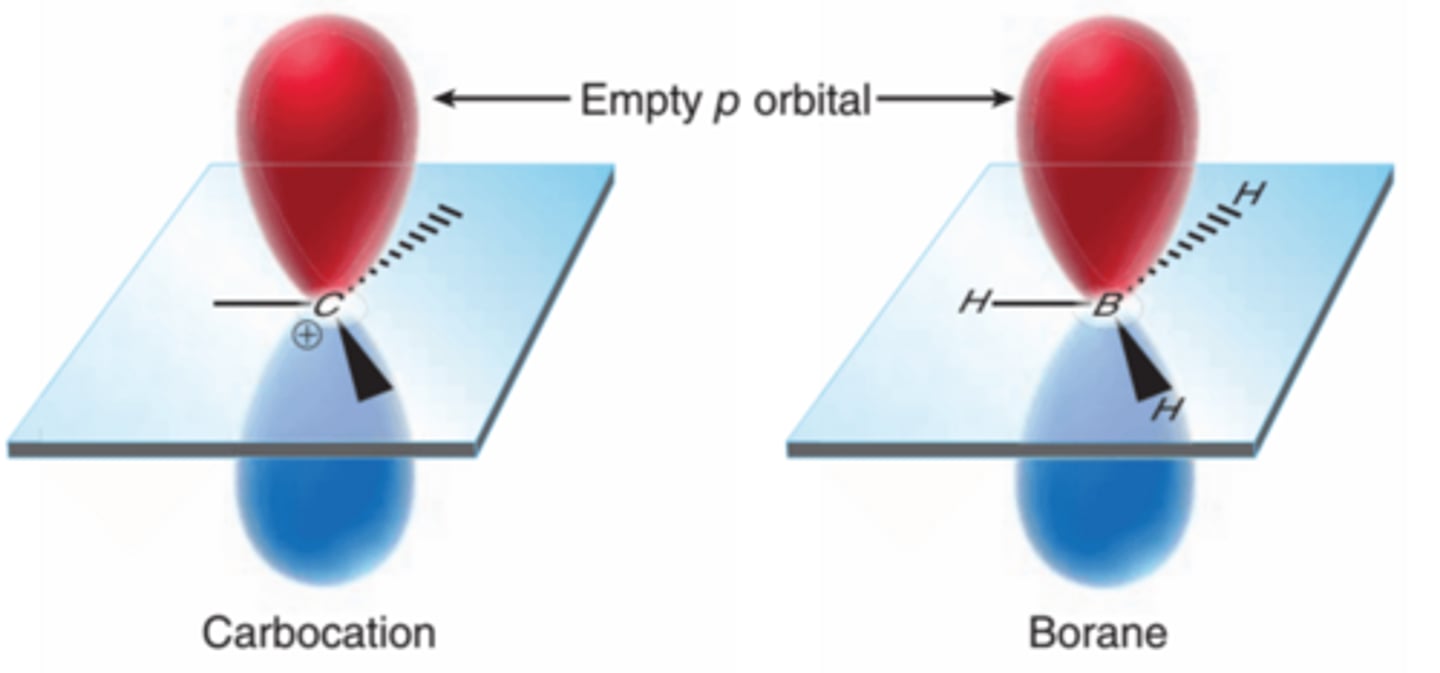

Reagents for Hydroboration-Oxidation

The structure of borane(BH3) is similar to that of a carbocation, but without a charge(1st example in image). The boron atom lacks an octet of electrons and is therefore very reactive

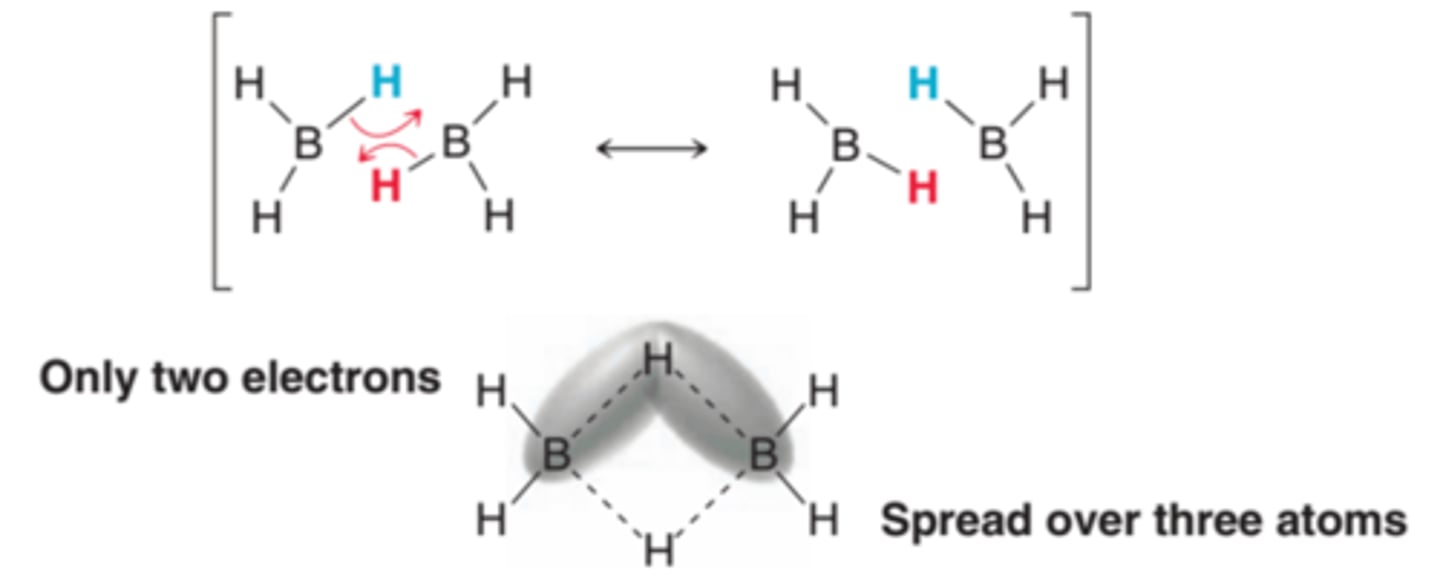

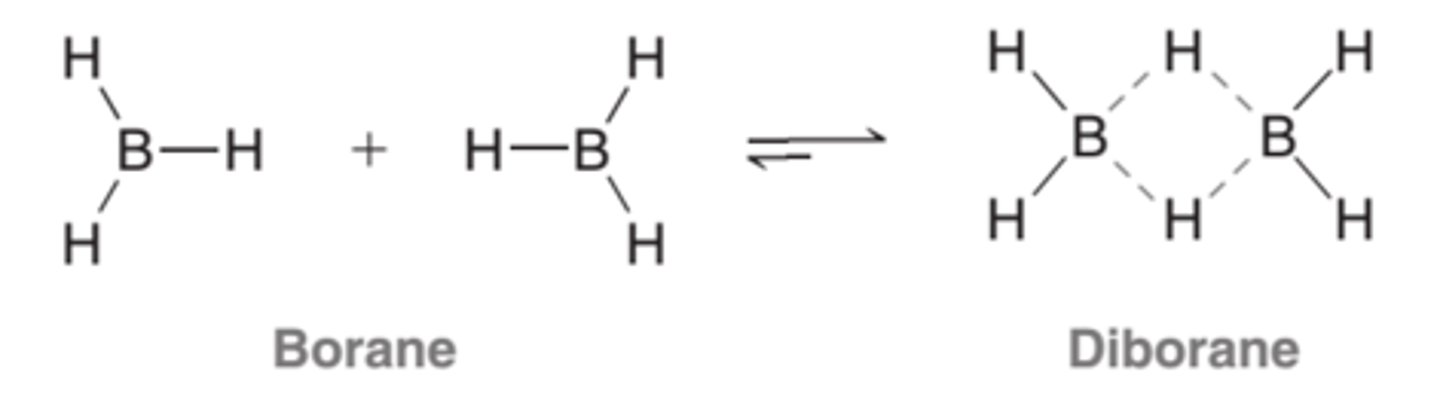

Diborane

Borane is so reactive that one borane molecule will even react with another borane molecule to form a dimeric structure called diborane which is a dimer believed to possess a special type of bonding which can be more easily understood by drawing the resonance structure shown in the 1st example in this image. Each of the hydrogen atoms is partially bonded to two boron atoms using a total of two electrons(2nd example in image). Such bonds are called three-center, two-electron bonds

Borane and Diborane Equilibrium

Borane and diborane coexist in an equilibrium that lies very much to the side of diborane(B2H6), leaving very little borane(BH3) present at equilibrium

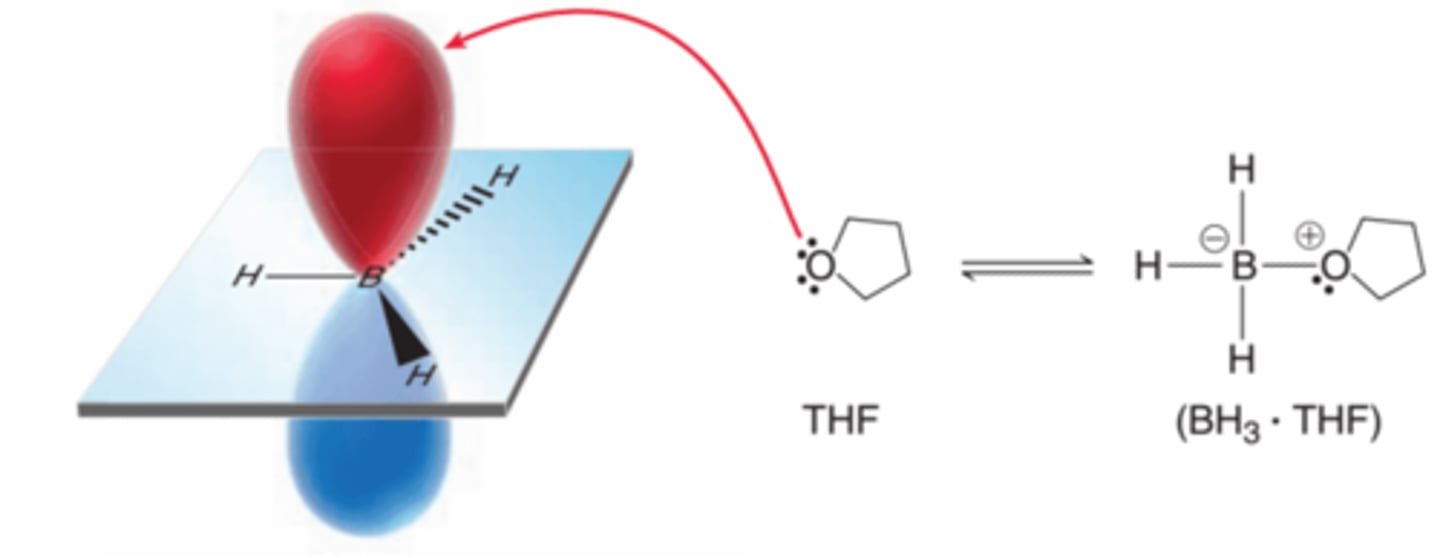

Stabilizing Borane with THF

Is is possible to stabilize BH3, thereby increasing its concentration at equilibrium, by using a solvent such as THF(tetrahydrofuran), which can donate electron density into the empty p orbital of boron(example in image). The boron atom is still very electrophilic and subject to attack by the pi bond of an alkene even after it receives some electron density from the solvent

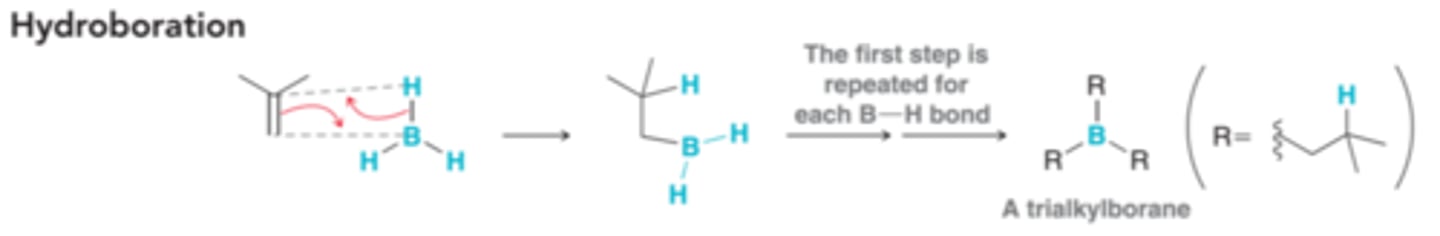

Mechanism for Hydroboration-Oxidation

A BH2 groups is installed at the less substituted carbon and is ultimately replaced with an OH group. Consists of Hydroboration and then oxidations

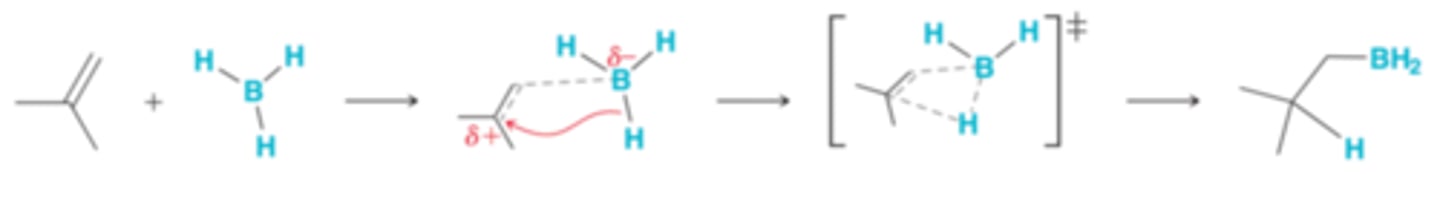

Mechanism for Hydroboration(1st step of Hydroboration-Oxidation Reaction)

Regioselectivity of Hydroboration-Oxidation

The preference for BH2 to be positioned at the less substituted carbon can be explained in terms of electronic or steric considerations. It is likely that both electronic and steric factors contribute to the observed regioselectivity for hydroboration-oxidation

Electronic Considerations for Regioselectivity of Hydroboration-Oxidation

In the first step of the proposed mechanism, attack of the pi bond triggers a simultaneous hydride shift. However, this process does not have to be perfectly simultaneous. As the pi bond attacks the empty p orbital of boron, one of the vinylic positions can begin to develop a partial positive charge(+δ). There will be a preference for any positive character to develop at the more substituted carbon. In order to accomplish this, the BH2 group must be positioned at the less substituted carbon atom

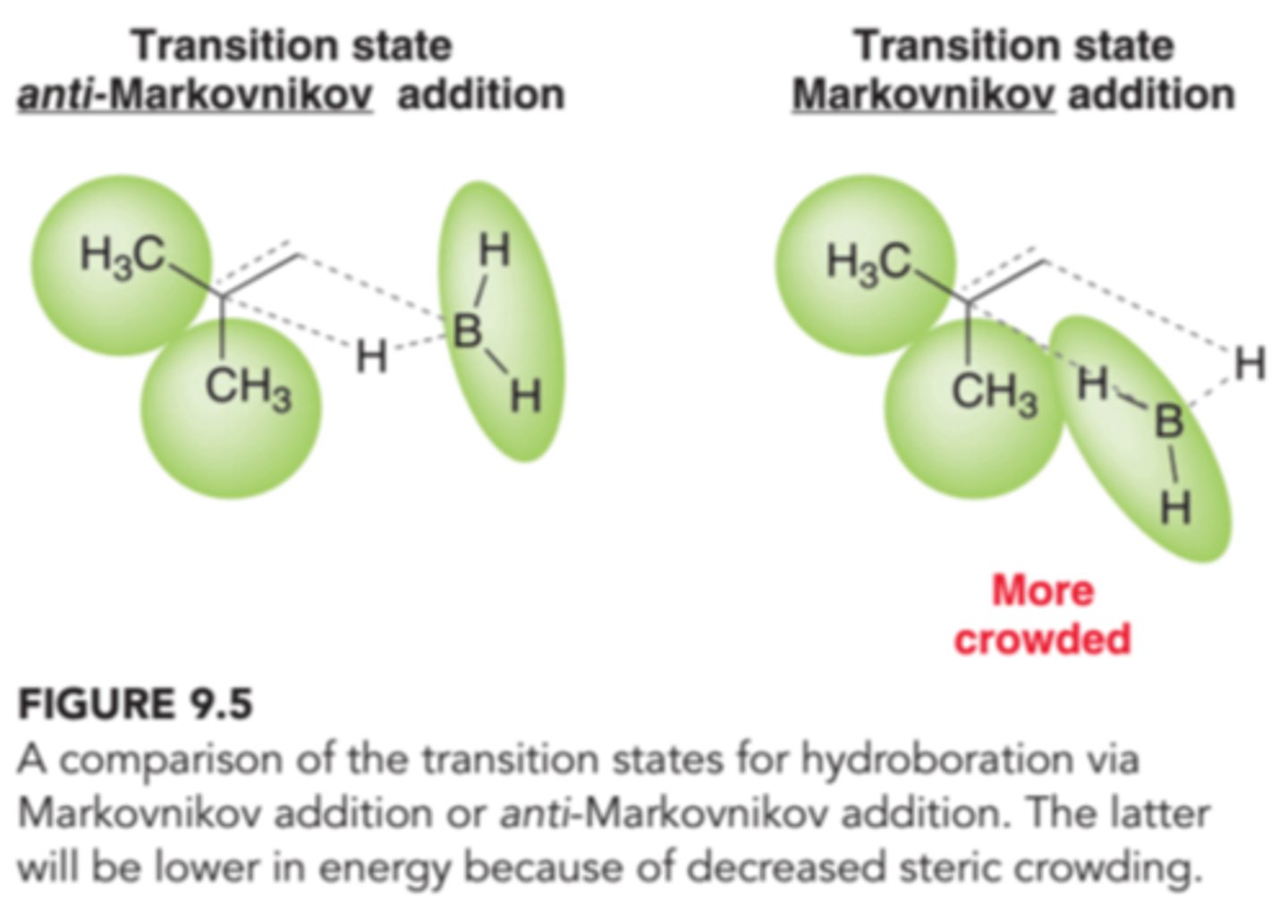

Steric Considerations for Regioselectivity of Hydroboration-Oxidation

In the first step of the proposed mechanism, both H and BH2 are adding across the double bond simultaneously. Since BH2 is bigger than H, the transition state will be less crowded and lower in energy if the BH2 group is positioned at the less sterically hindered position.

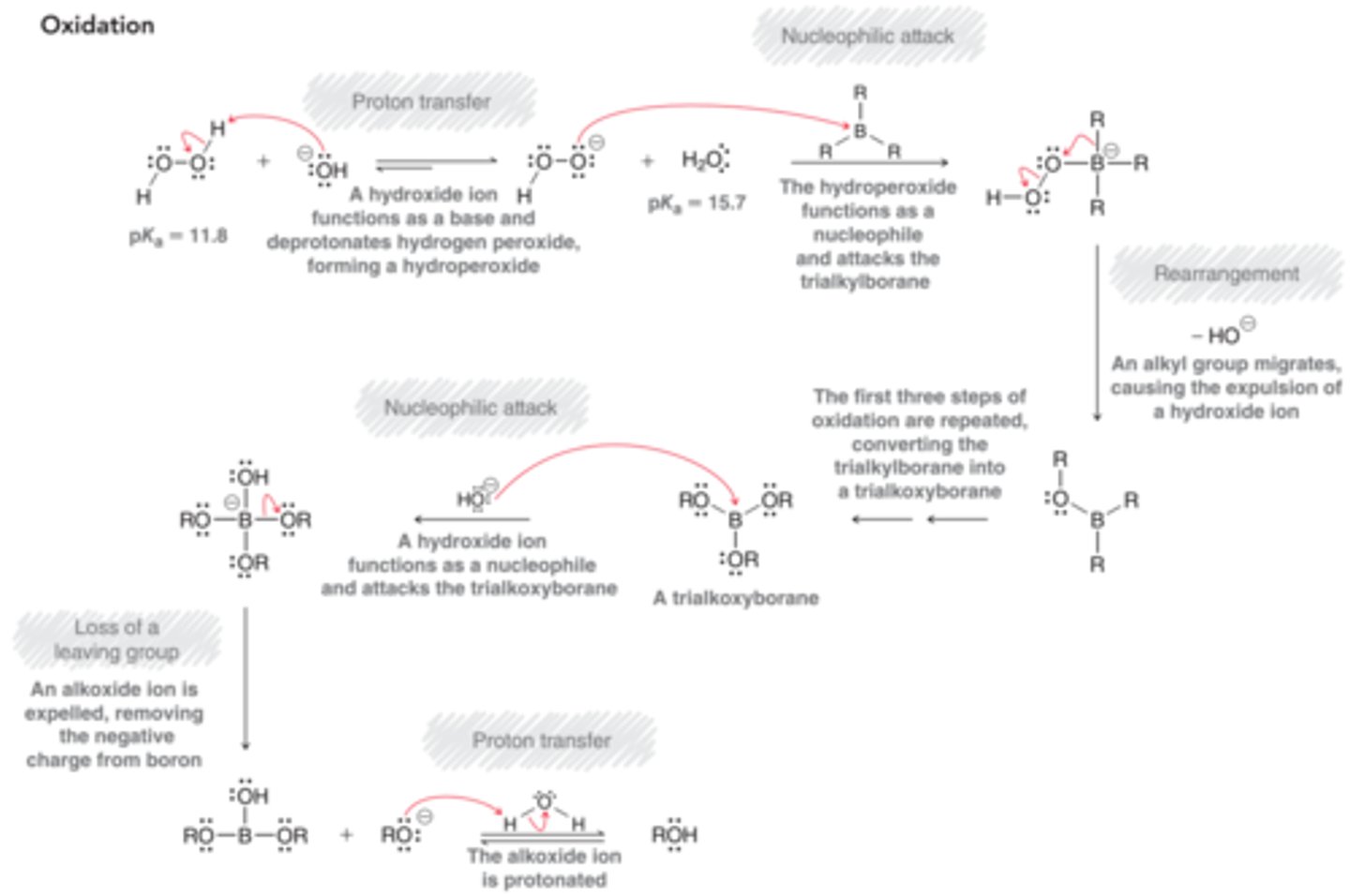

Mechanism for Oxidation(2nd step of Hydroboration-Oxidation Reaction)

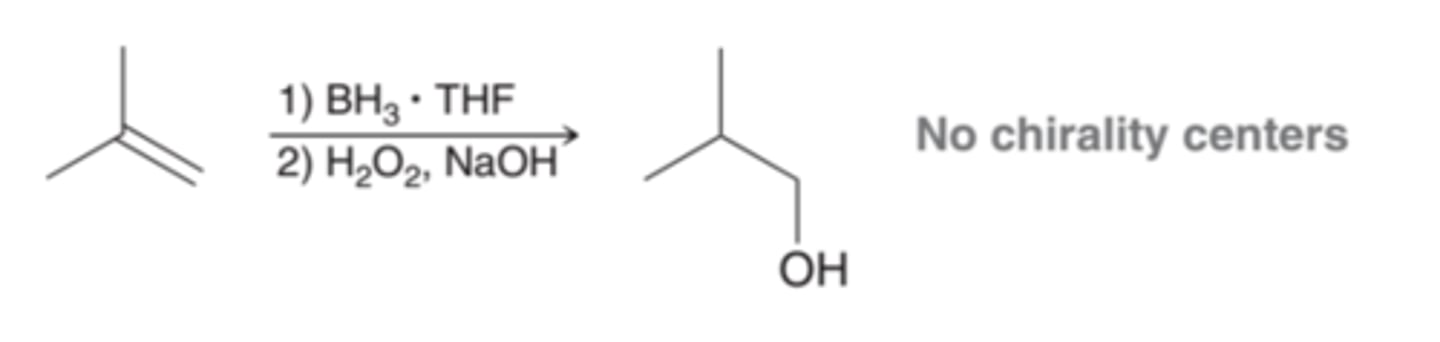

No Chirality Center Formation and Stereospecificity of Hydroboration-Oxidation

If no chirality centers are formed, then the stereoespecificty of the reaction is not relevant. In this case, only one product is formed , rather than a pair of enantiomers, and the syn requirement is irrelevant.

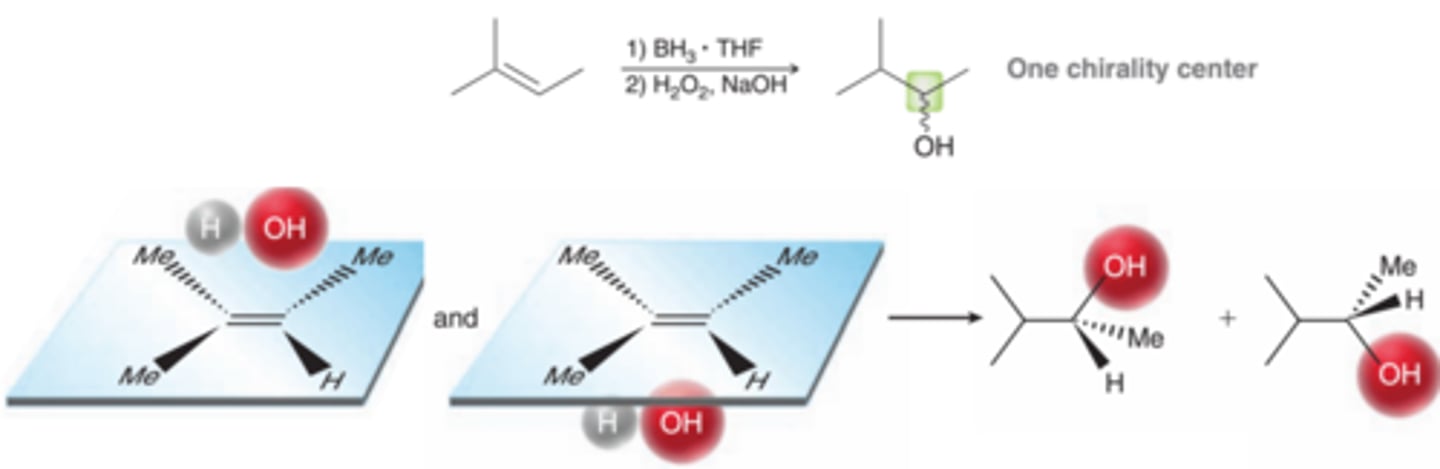

Single Chirality Center Formation and Stereospecificity of Hydroboration-Oxidation

Now consider the stereochemical outcome in a case where one chirality center is formed(1st example in image). In this case, both enantiomers are obtained, because syn addition can take place from either face of the alkene with equal likelihood(2nd example in image)

Two Chirality Center Formations and Stereospecificity of Hydroboration-Oxidation

Now consider a case in which two chirality centers are formed(1st example in image). In such a case, the requirement for syn addition determines which pair of enantiomers is obtained(2nd example in image). The other two possible stereoisomers are not obtained

Catalytic Hydrogenation

Involves the addition of molecular hydrogen(H2) across a double bond in the presence of a metal catalyst. The net result of this process is to reduce an alkene to an alkane

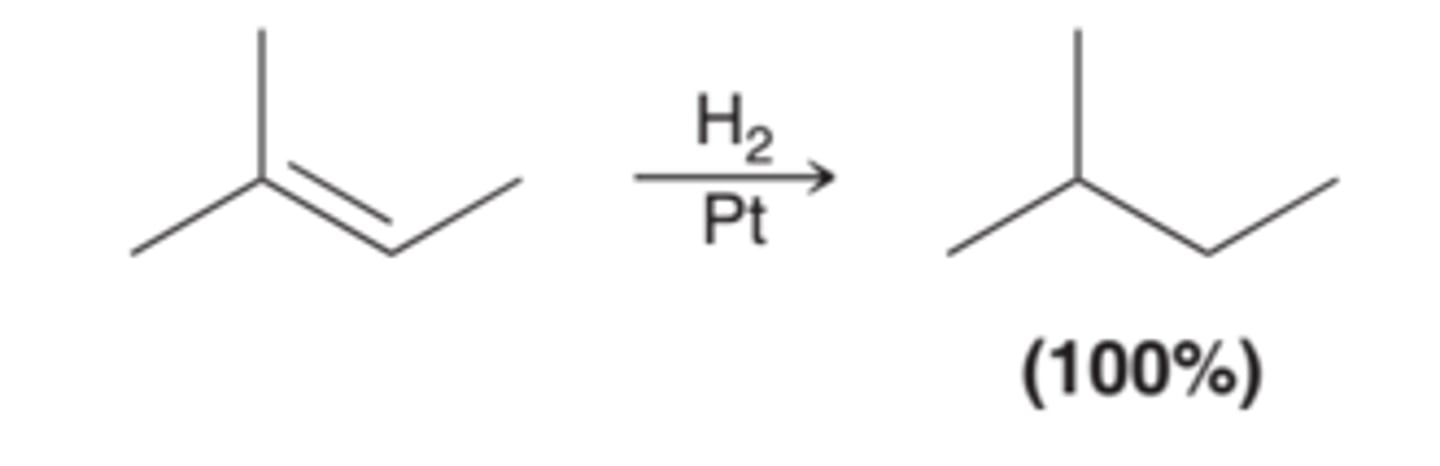

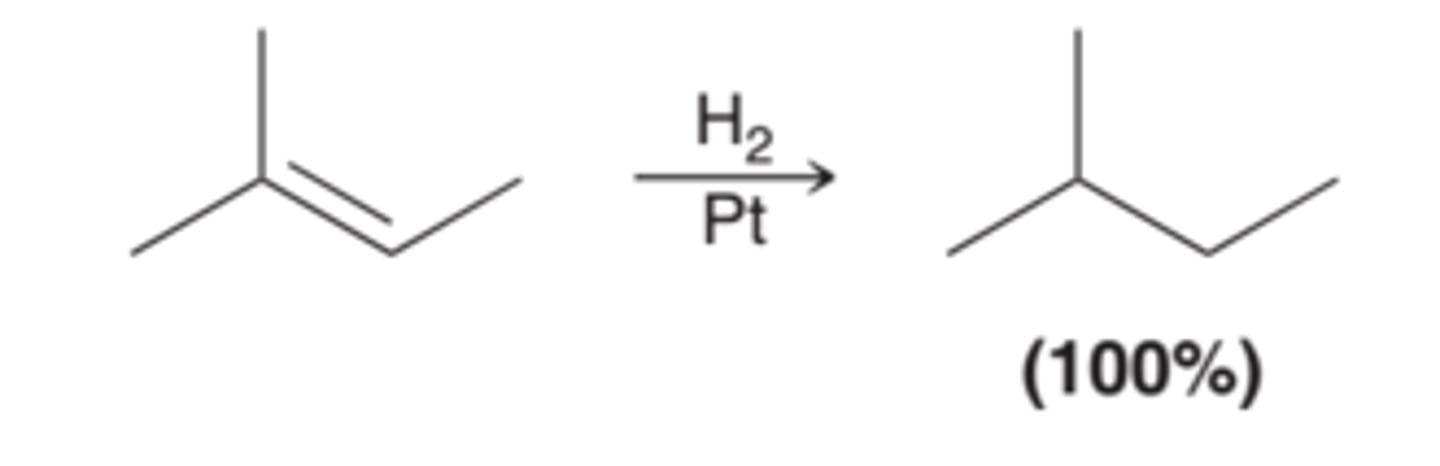

No Chirality Center Formation and Stereospecificity of Catalytic Hydrogenation

In the reaction in this image, there are no chirality centers in the product, so the stereospecificity of the process is irrelevant.

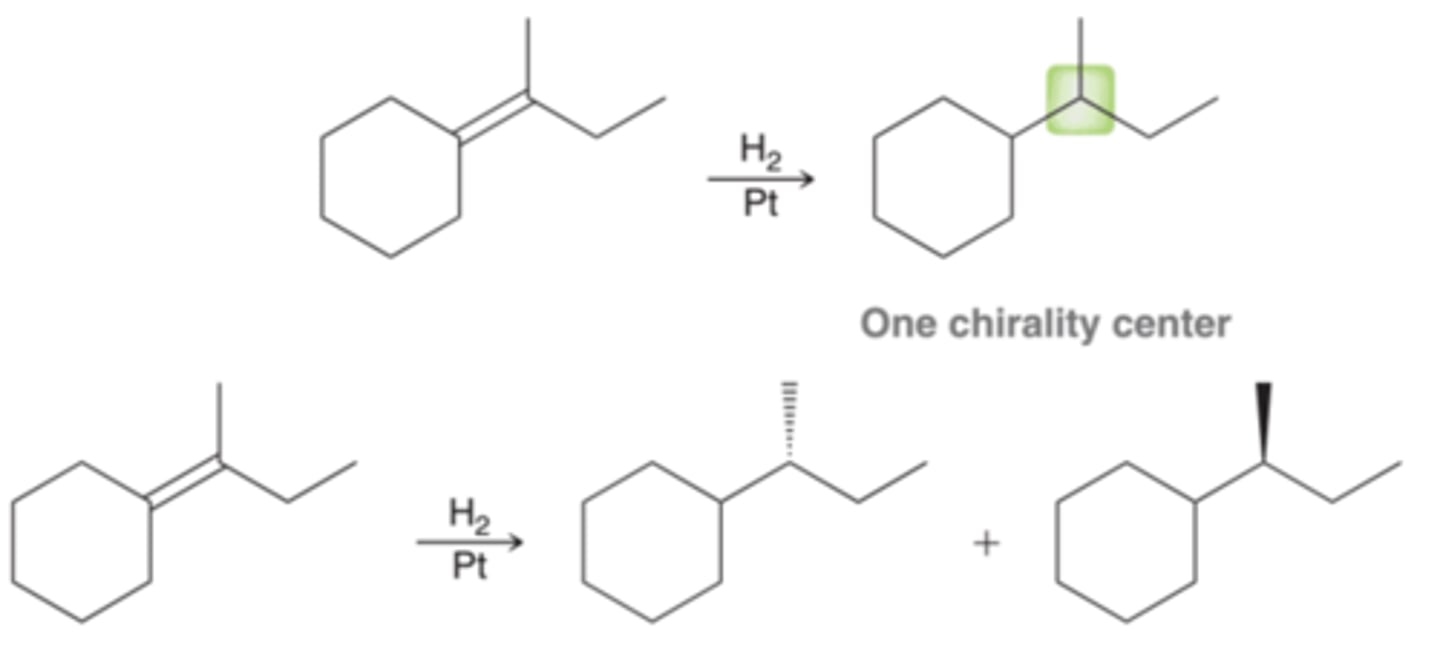

Single Chirality Center Formation and Stereospecificity of Catalytic Hydrogenation

When only one chirality center is formed, both possible enantiomers are formed because syn addition can occur from either face of the pi bond with equal likelihood

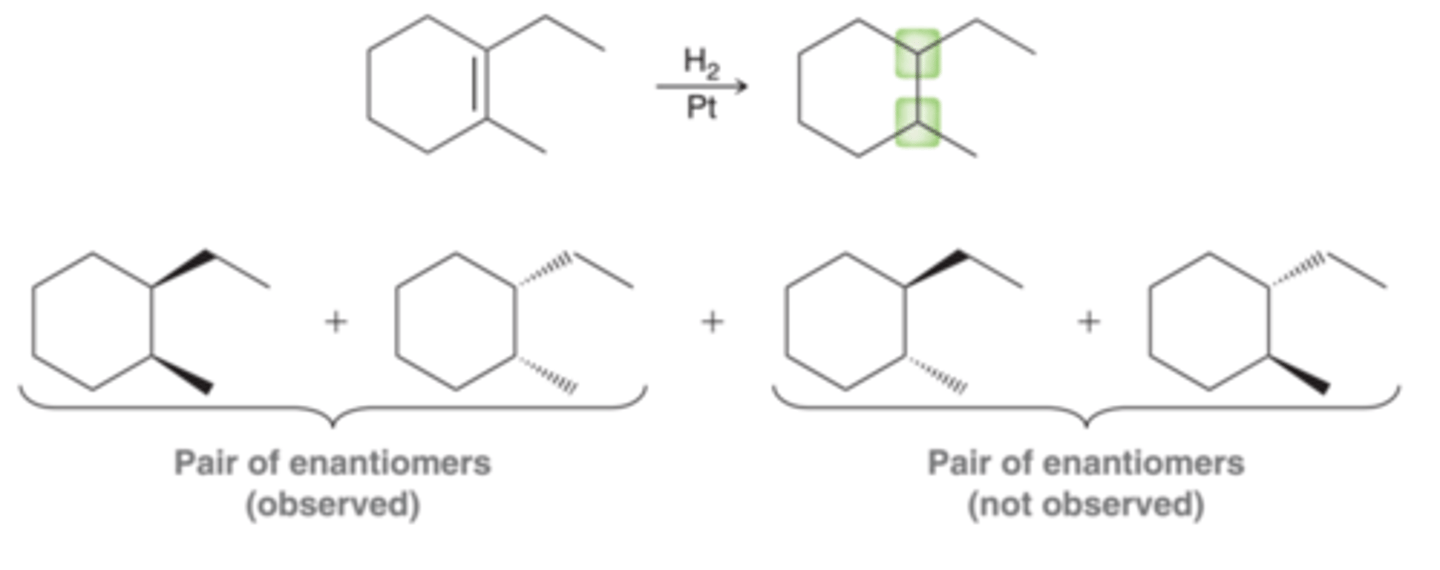

Two Chirality Center Formations and Stereospecificity of Catalytic Hydrogenation

In a case where two new chirality centers are being formed, there are four possible stereoisomeric products(two pairs of enantiomers) but only the pair of enantiomers that results from syn addition forms

The Role of the Catalyst in Catalytic Hydrogenation

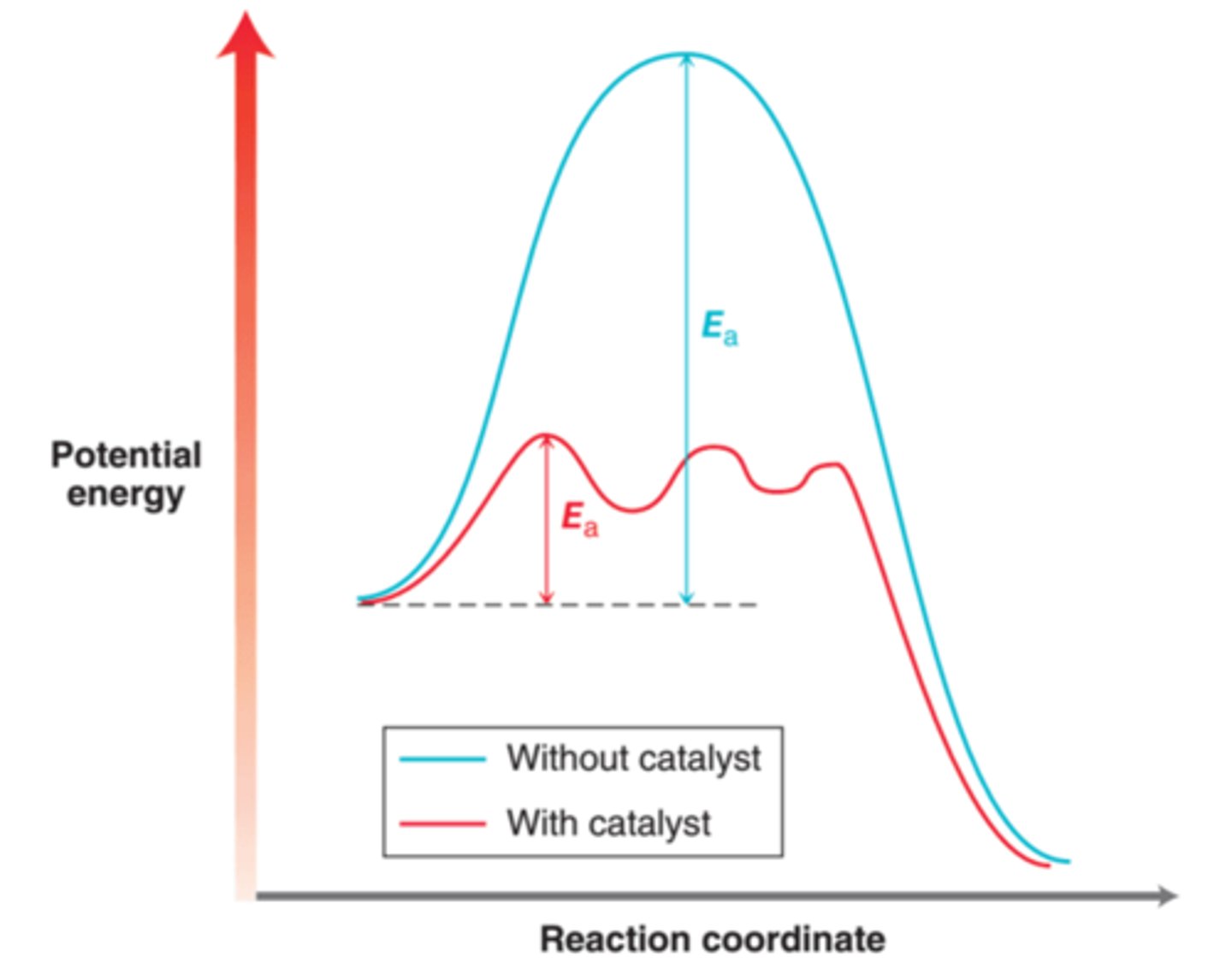

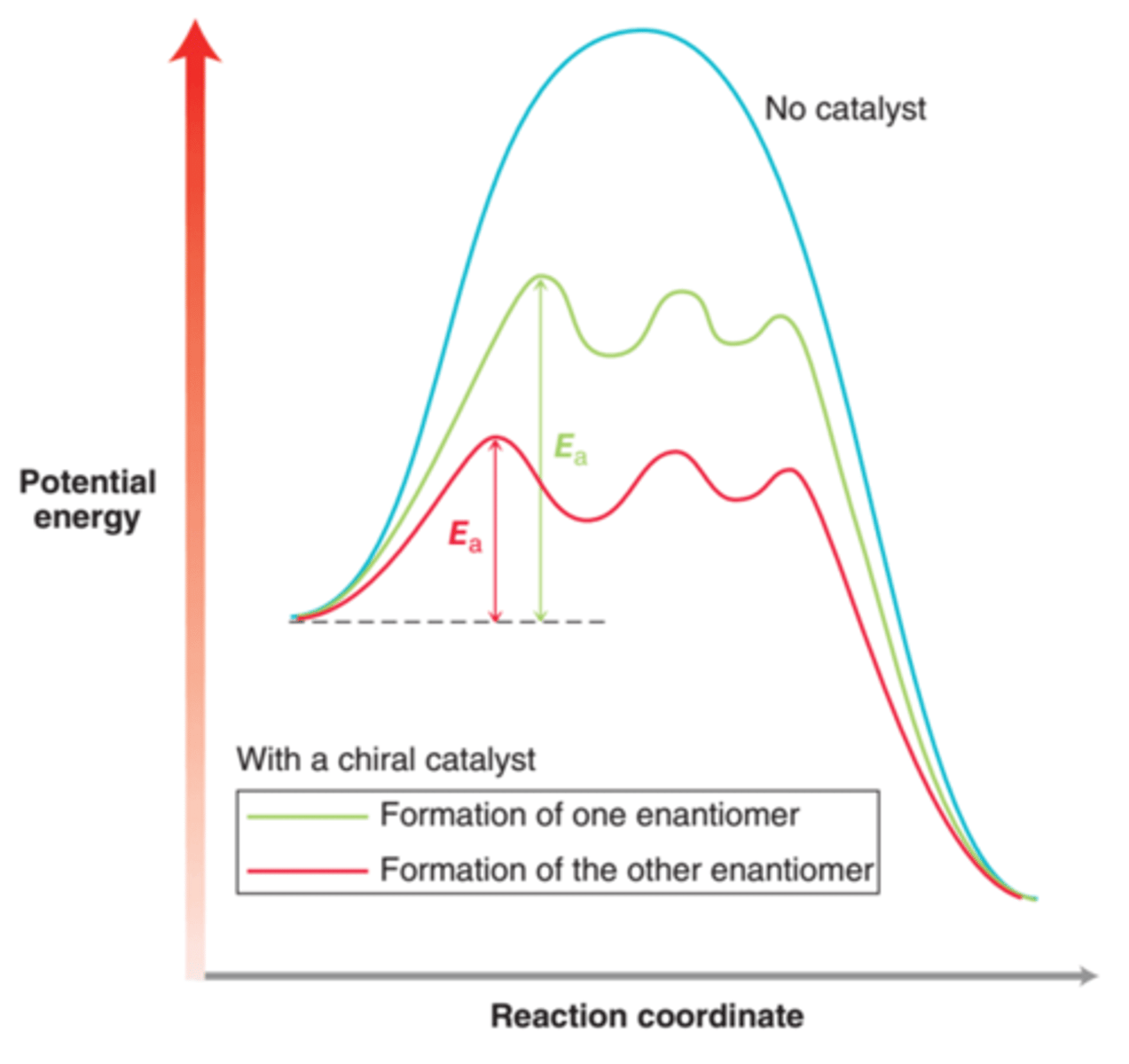

Catalytic hydrogenation is accomplished by treating an alkene with H2 gas and a metal catalyst, often under conditions of high pressure. The role of the catalyst is shown in energy diagram in this image. The pathway without the metal catalyst(blue) has a very large energy of activation(Ea), rendering the reaction too slow to be of practical use. The presence of a catalyst provides a pathway(red) with a lower energy of activation, thereby allowing the reaction to occur more rapidly

Metal Catalyst in Catalytic Hydrogenation

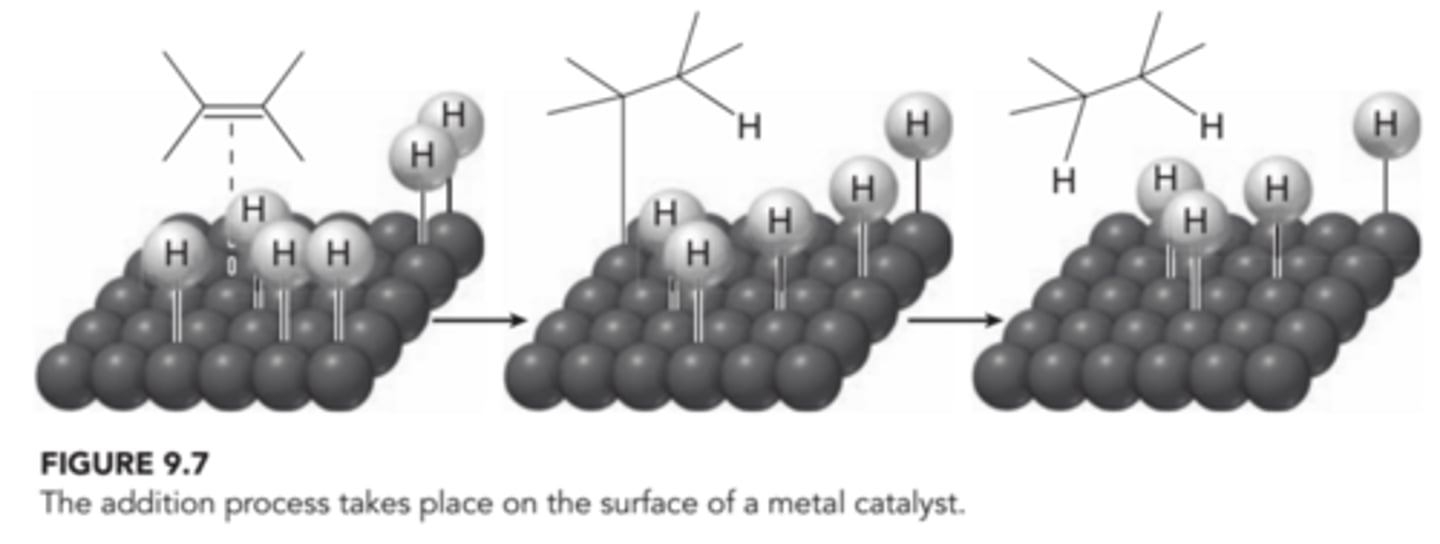

A variety of metal catalysts can be used, such as Pt, Pd, or Ni. The process is believed to begin when molecular hydrogen(H2) interacts with the surface of the metal catalyst, effectively breaking the H-H bonds and forming individual hydrogen atoms adsorbed to the surface of the metal. The alkene coordinates with the metal surface, and the surface chemistry allows for the reaction between the pi bond and two hydrogen atoms, effectively adding H and H across the alkene. In this process, both hydrogen atoms add to the same face of the alkene, explaining the observed stereospecificity(syn addition)

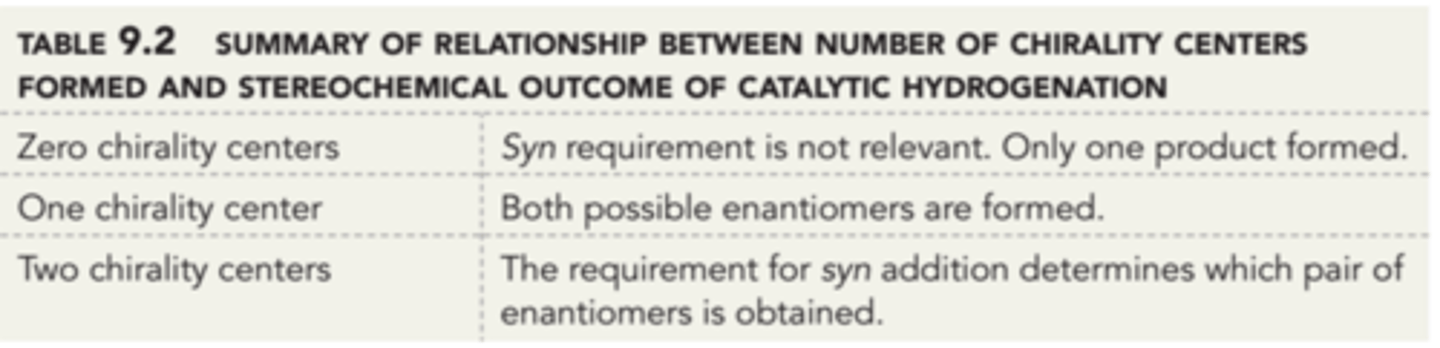

Summary of Relationship Between Number of Chirality Centers Formed and Stereochemical Outcome of Catalytic Hydrogenation

In any given case, the stereochemical outcome is dependent on the number of chirality centers formed in the process.

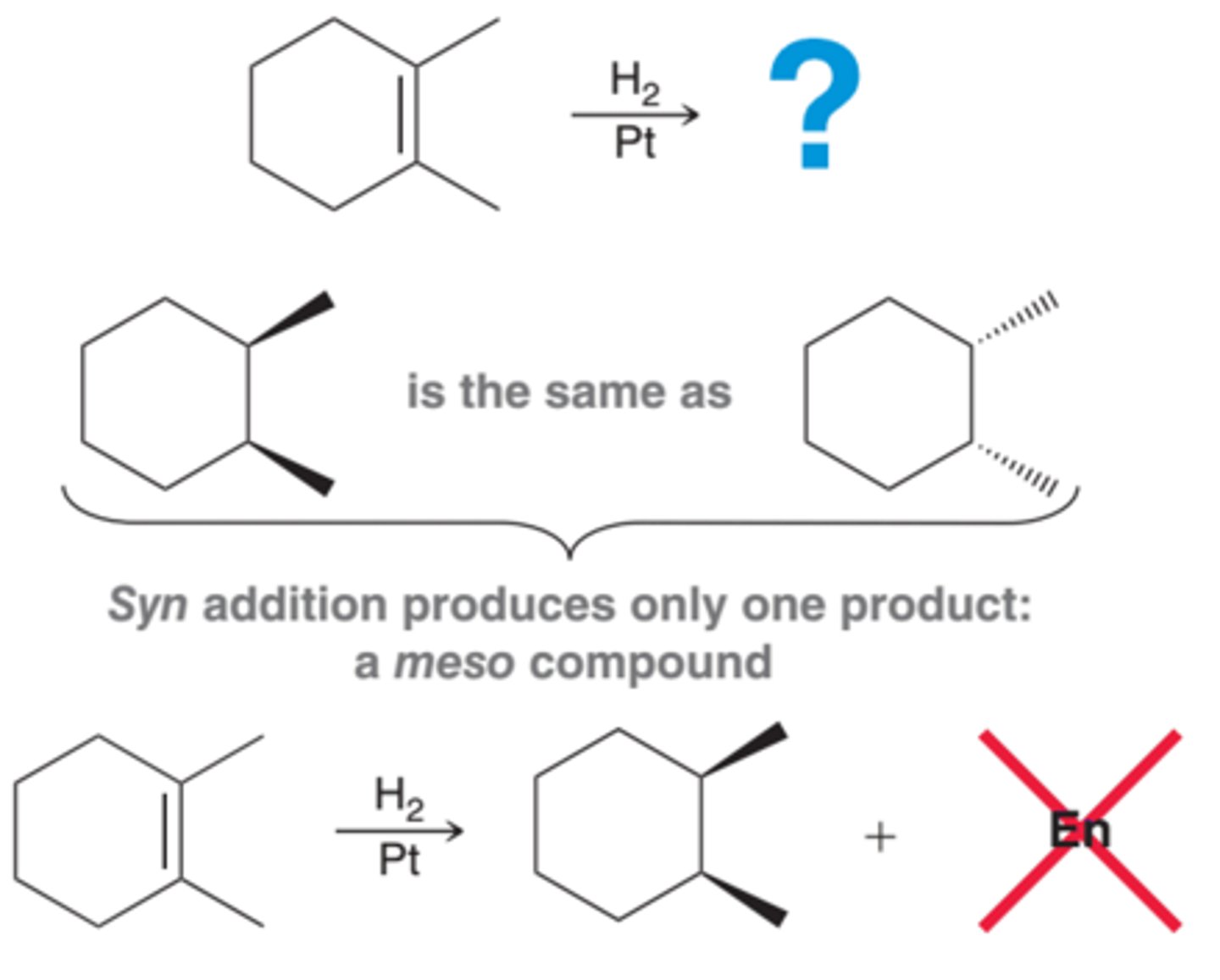

Meso Compound Formation and Catalytic Hydrogenation

Symmetrical alkenes will produce a meso compound rather than a pair of enantiomers. In the 1st example in image, two new chirality centers are formed, however, in this case, there is only one product from syn addition, not a pair of enantiomers(2nd example in image). A meso compound, by definition, does not have an enantiomer. A syn addition on one face of the alkene generates exactly the same compound as a syn addition on the other face. And, therefore, care must be taken not to write "+ Enantiomer" or "+ En" for short(3rd example in image)

Heterogenous Catalysts

Catalysts that do not dissolve in the reaction medium. Ex: Pt, Pd, Ni

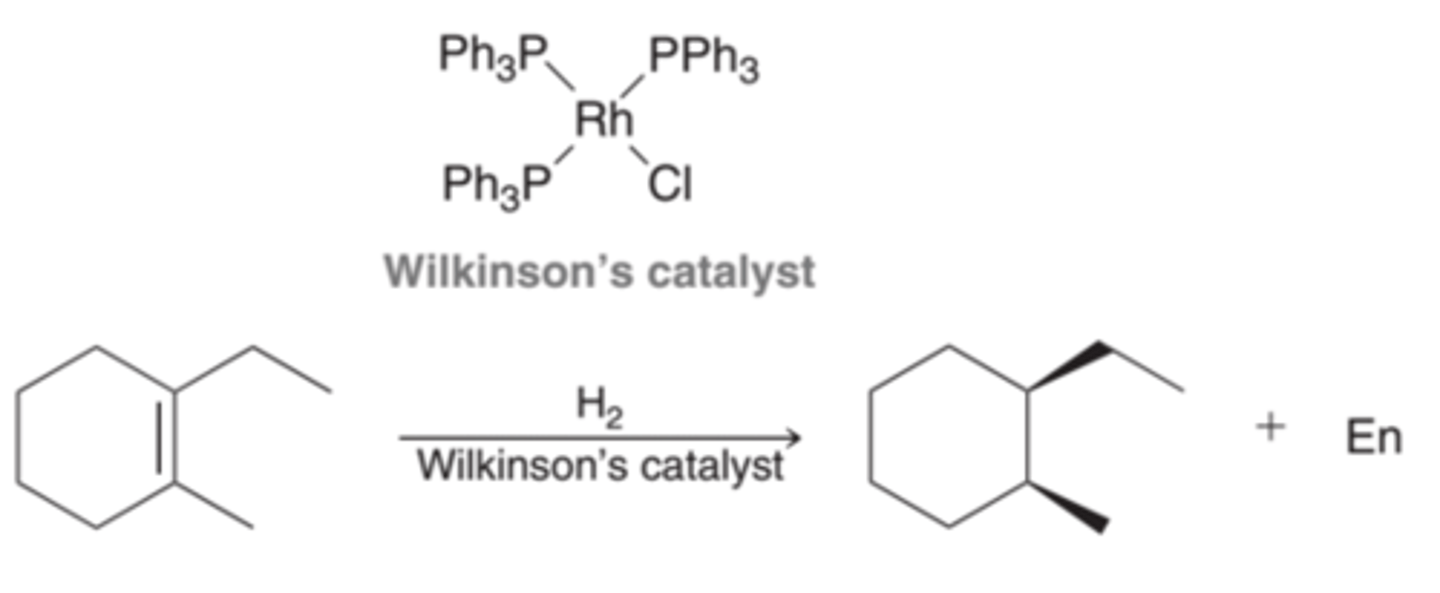

Homogenous Catalysts

Catalysts that are soluble in the reaction medium. The most common homogenous catalyst for hydrogenation is called Wilkinson's catalyst(1st example in image). With homogenous catalysts, a syn addition is also observed(2nd example in image).

Asymmetric Hydrogenation

Catalytic hydrogenation in which the production of one enantiomer is favored over the production of the other, leading to an observed enantiomeric excess(ee). This is done using a chiral catalyst which is capable of lowering the energy of activation for formation of one enantiomer more dramatically than the other enantiomer.

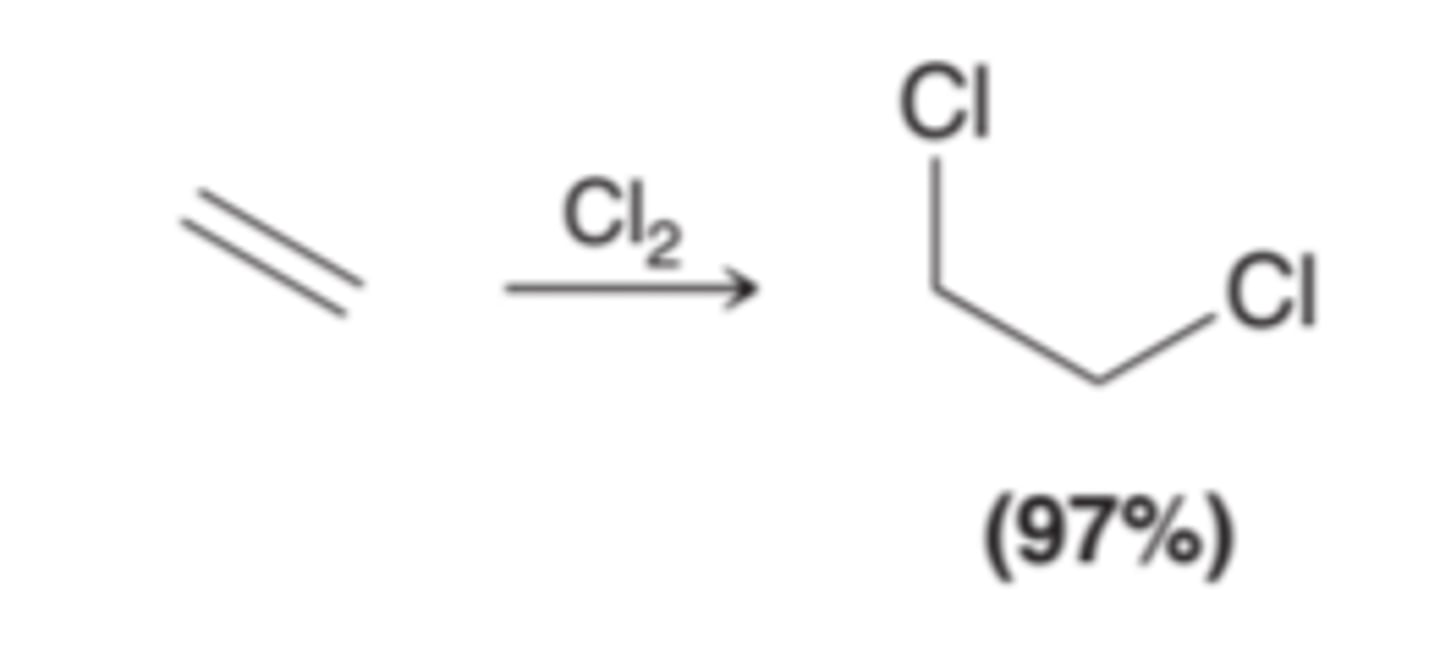

Halogenation

Involves the addition of X2(either Br2 or Cl2) across an alkene.

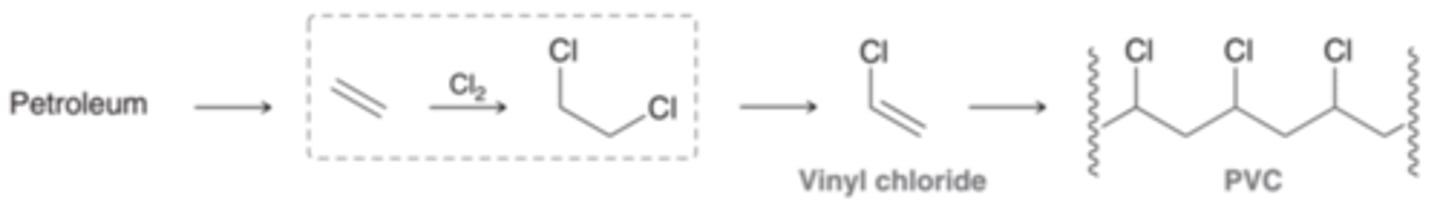

Halogenation and Production

This reaction is a key step in the industrial preparation of polyvinylchoride(PVC). Halogenation of alkenes is only practical for the addition of chlorine or bromine. Reaction with fluorine is too violent, and the reaction with iodine often produces very low yields

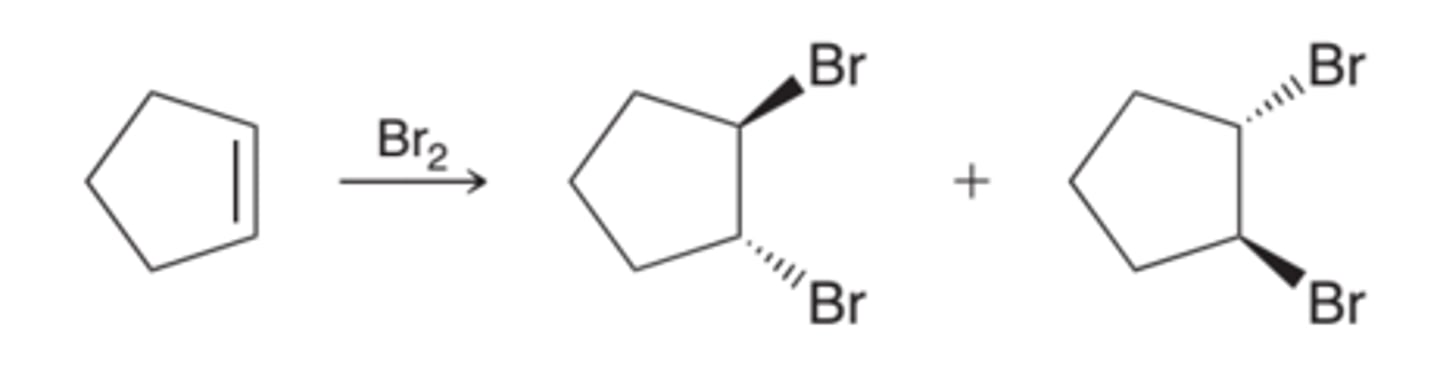

Stereospecifity of Halogenation

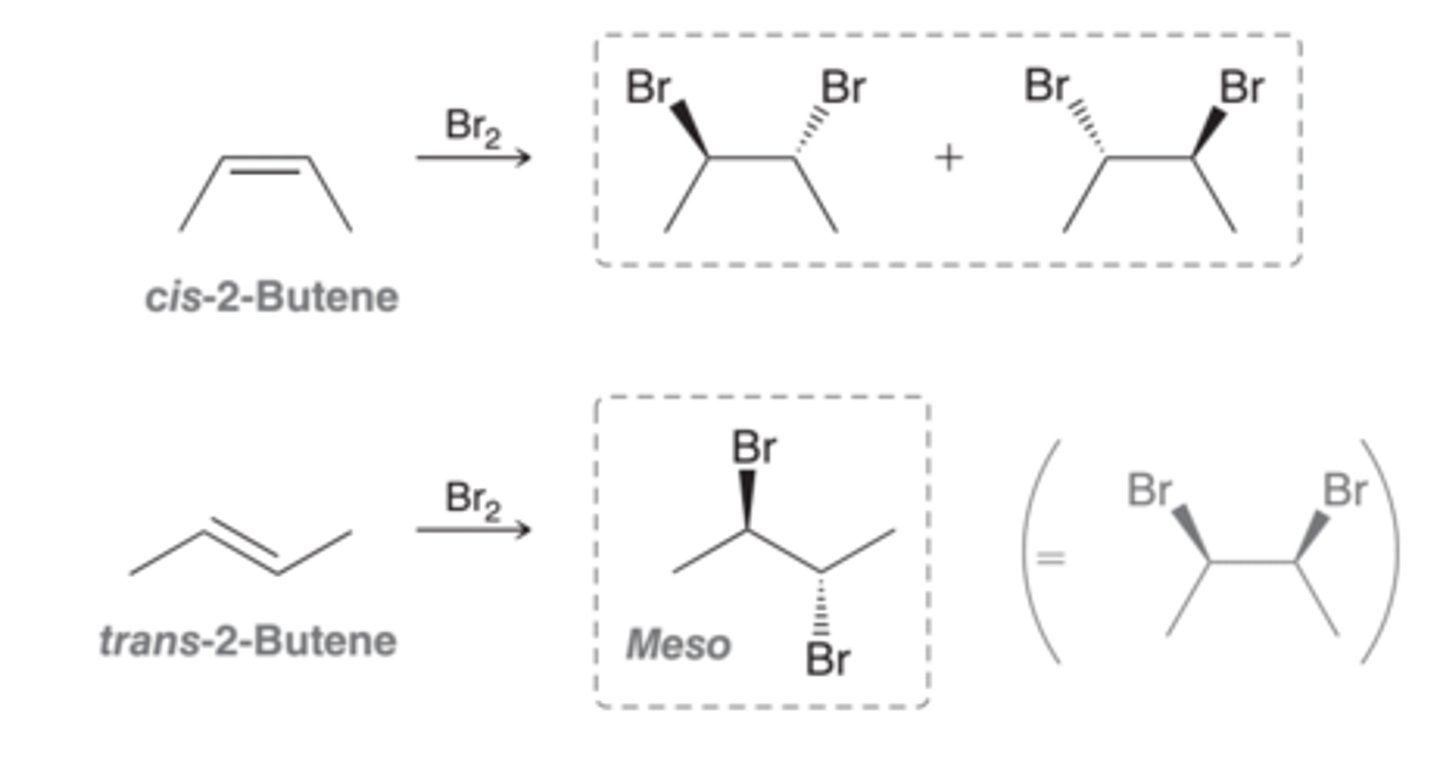

The addition occurs in a way that places the two halogen atoms on opposite sides of the pi bond. This mode of addition is called an anti addition. For most simply alkenes, halogenation appears to proceed primarily via an anti addition

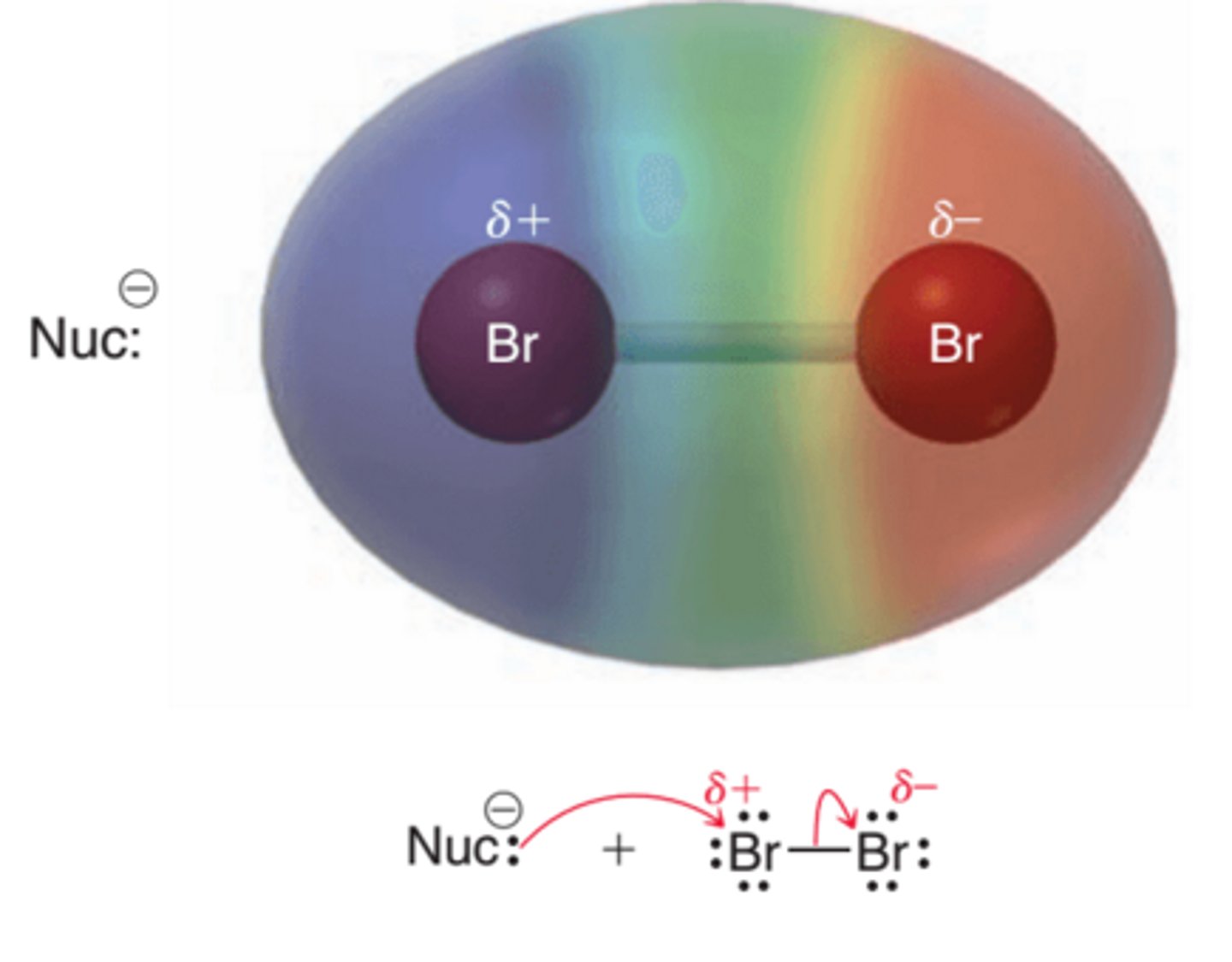

Molecular Bromine

Molecular bromine is a nonpolar compound, because the Br-Br bond is covalent. Nevertheless, the molecule is polarizable, and the proximity of a nucleophile can cause a temporary, induced dipole moment(1st example in image). This effect places a partial positive charge on one of the bromine atoms, rendering the molecule electrophilic and many nucleophiles are known to react with bromine(2nd example in image)

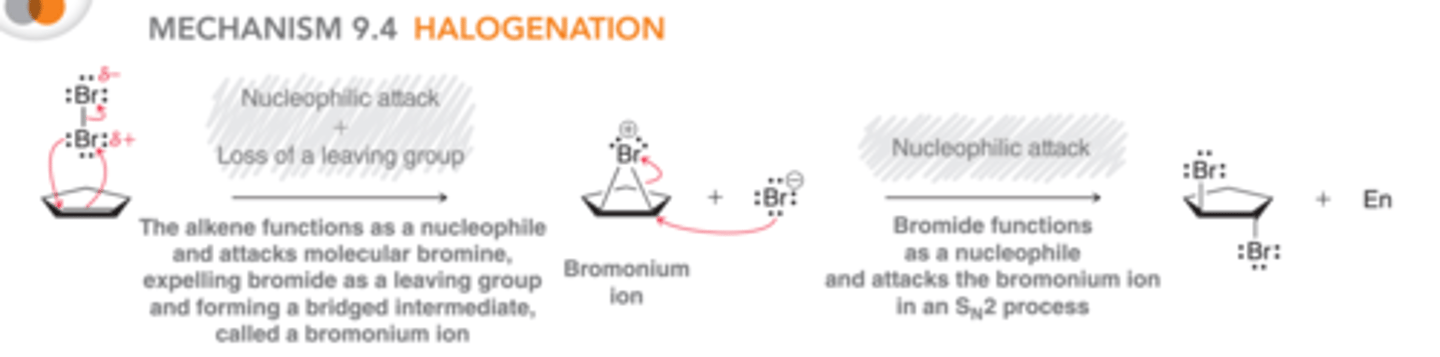

Mechanism for Halogenation

In this mechanism, an additional curved arrow has been introduced, forming a bridged intermediate rather than a free carbocation. This bridged intermediate is called a bromonium ion. In the second step, the bromonium ion is attacked by the bromide ion that was produced in the first step via an SN2 process which proceed via back-side attack which leads to the observed stereochemical requirement for anti addition

Bromonium Ion

Is similar in structure and reactivity to the mercurinium ion

Stereochemical Outcome of Halogenation

The stereochemical outcome for halogenation reactions is dependent on the configuration of the starting alkene. In this image, anti addition across cis-2-butene leads to a pair of enantiomers, while anti addition across trans-2-butene leads to a meso compound. The configuration of the starting alkene determined the configuration of the product for halogenation reactions

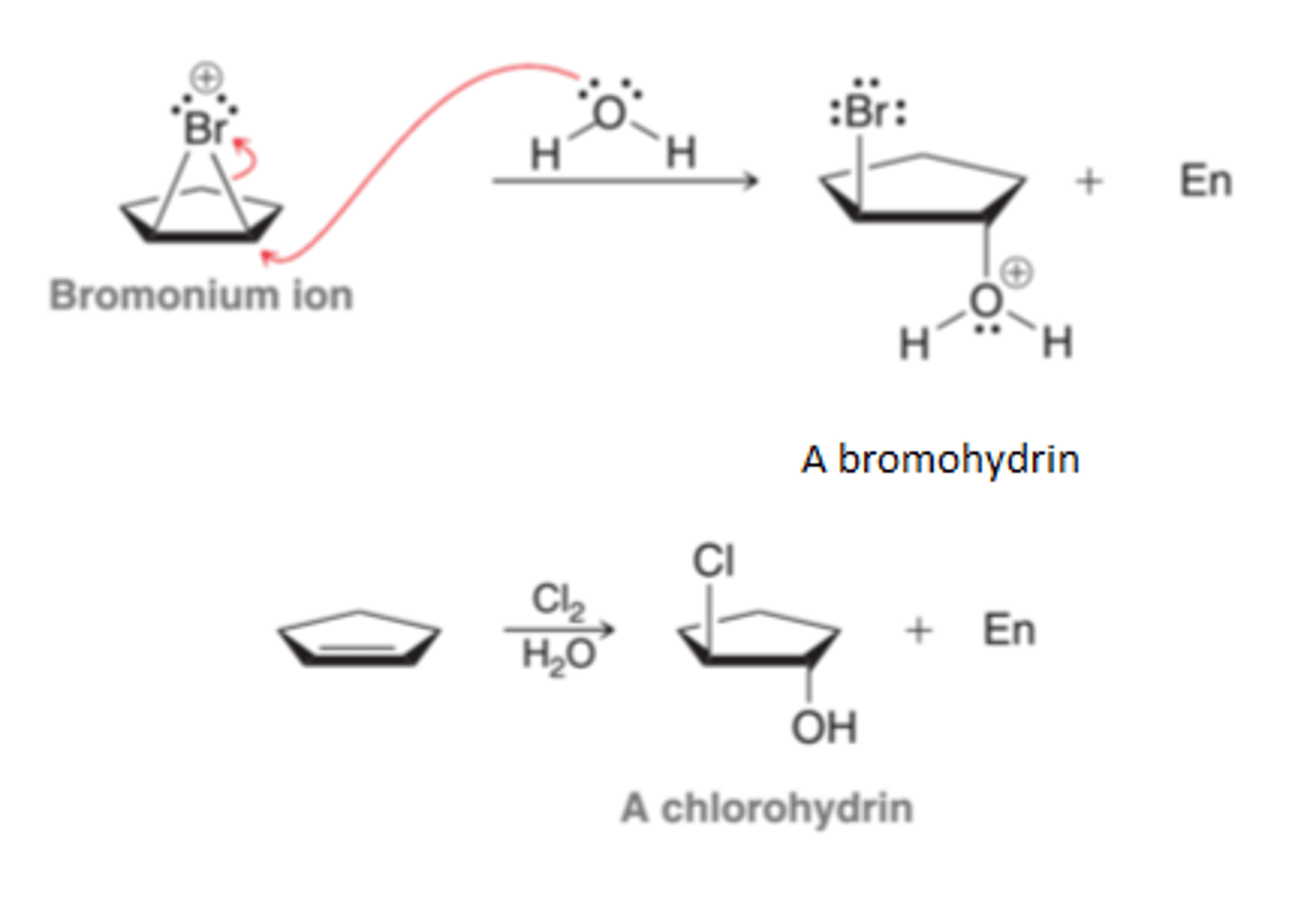

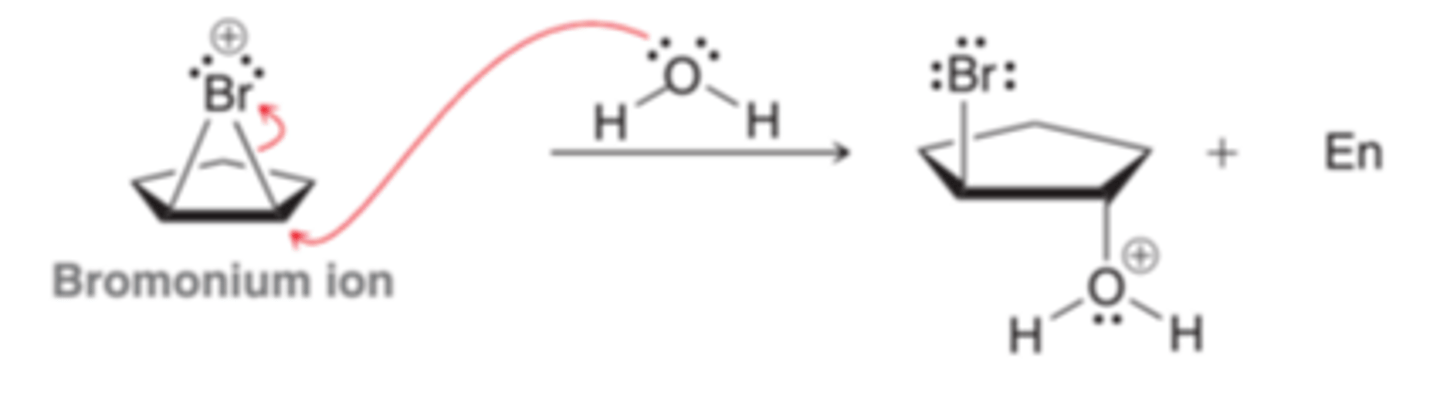

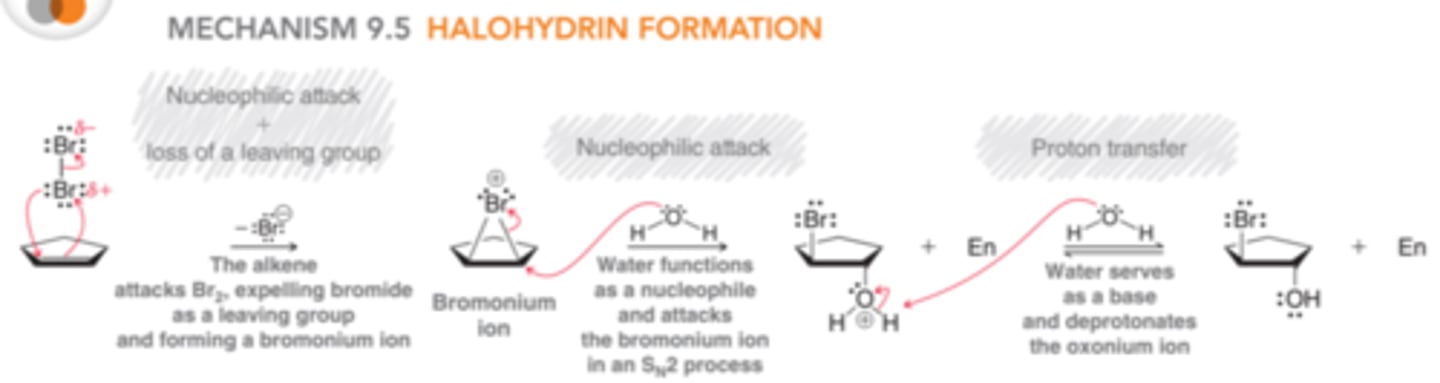

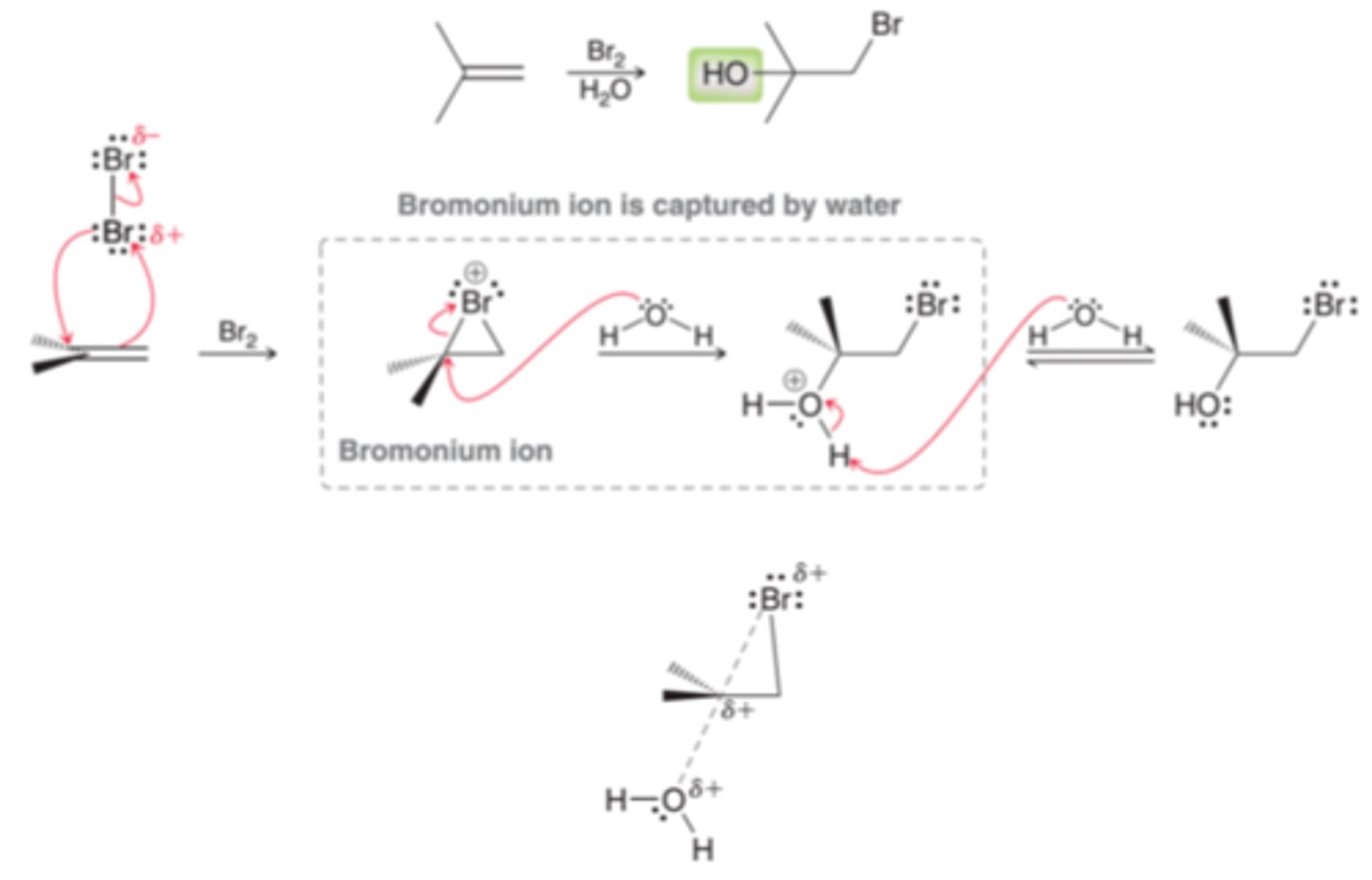

Halohydrin Formation

The addition of Br and OH across an alkene which occurs when a molecular halogen is used in the presence of water. When bromine is used in the presence of water, the product is called bromohydrin and when chlorine is used in the presence of water, the product is called chlorohydrin

Process of Halohydrin Formation

When bromination occurs in the presence of water(nucleophilic solvent), the bromomium ion that is initially formed can be captured by a water molecule, rather than bromide because the intermediate bromonium ion is a high-energy intermediate and will react with any nucleophile that in encounters. When water is the solvent, it is more likely that the bromonium ion will be captured by a water molecule before having a chance to react with a bromide ion, resulting in the deprotonation of the oxonium ion.

Mechanism for Halohydrin Formation

Regiochemistry of Halohydrin Formation

The OH is generally positioned at the more substituted position(1st example in image). In a halohydrin formation reaction, the positive charge is passed from one place to another. It begins on the bromine atom and ends up on the oxygen atom(2nd example in image). In order to do so, the positive charge must pass through a carbon atom in the transition state(3rd example in image). The transition state for this step will bear a partial carbocationic character and the more substituted carbon is more capable of stabilizing the partial positive charge and as a result, the transition state will be lower in energy when the attack takes place at the more substituted carbon atom

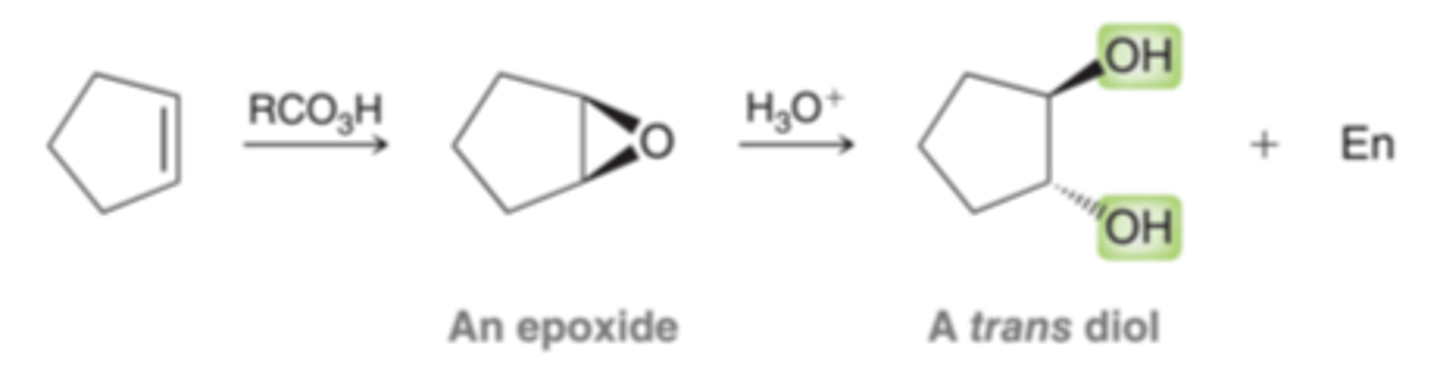

Dihyroxylation

Reactions that are characterized by the addition of OH and OH across an alkene. There are a number of reagents well suited to carry out this transformation. Some provide for an anti dihydroxylation, while others provide for a syn hydroxlation

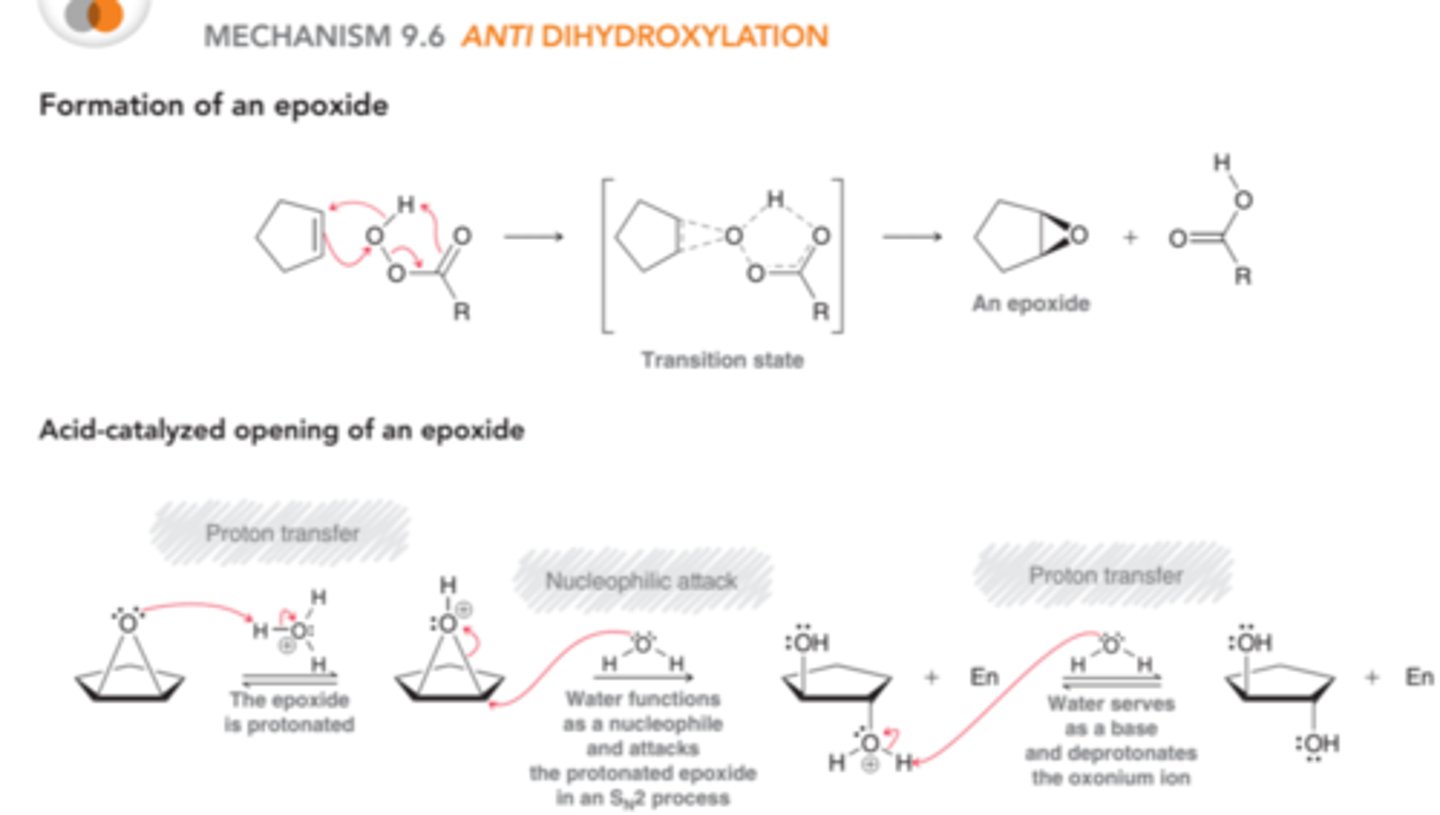

Anti Dihydroxylation

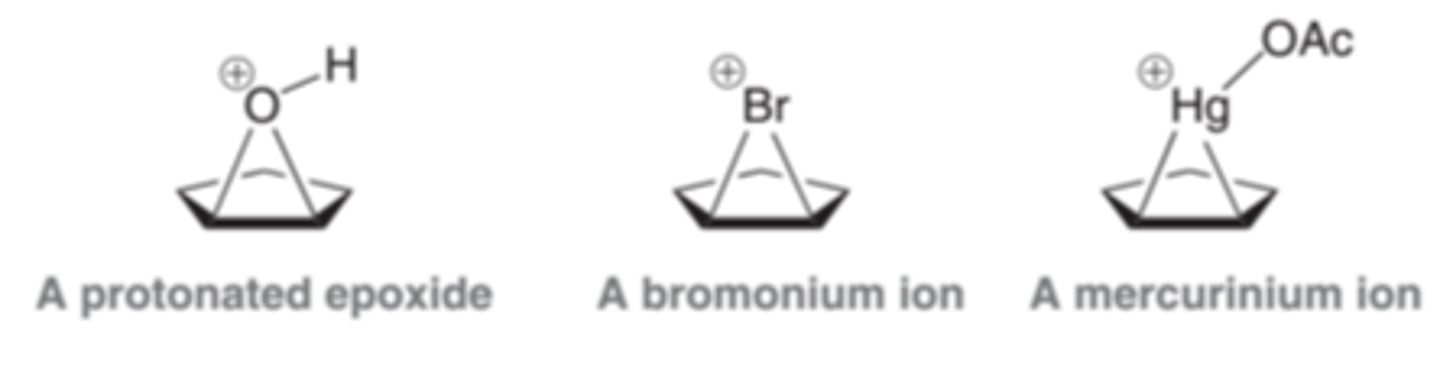

The first step of the process involves conversion of the alkene into an epoxide, and the second step involves opening the epoxide to form a trans diol. An epoxide is a three membered, cyclic ether

Mechanism for Anti Dihydroxylation

In the first part of the process, a peroxy acid(RCO3H) reacts with the alkene to form an epoxide. The epoxide is then protonated(in this case by acid) to produce an intermediate that is very similar to a bromonium or mercurinium ion. This intermediate can then be attacked through back-side attack by water(SN2). In the final step, the oxonium ion is deprotonated to yield a trans diol. H2O is used instead of OH to deprotonate because we are considering this reaction under acidic conditions, so hydroxide ions are not present in sufficient quantity to participate in reaction

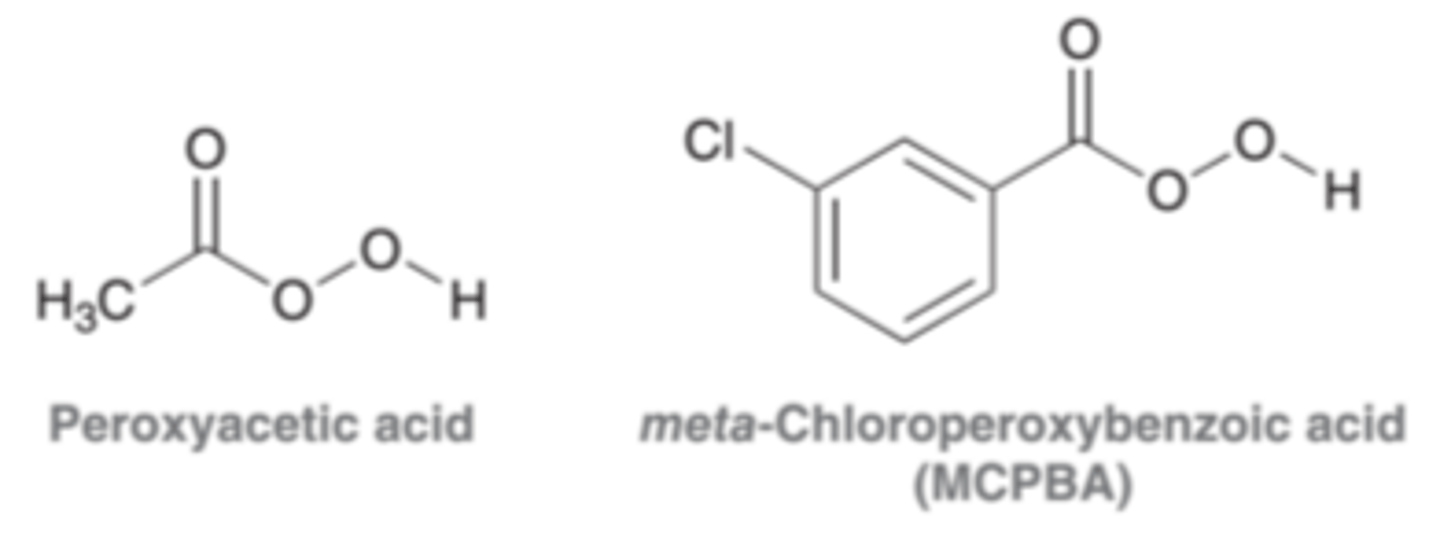

Peroxy Acids

Resemble carboxylic acids in structure, possessing just one additional oxygen atom. Peroxy acids are strong oxidizing agents and are capable of delivering an oxygen atom to an alkene in a single step, producing an expoxide

Protonated Epoxide

The protonated epoxide intermediate produced in anti dihydroxylation reactions is very similar to bromonium and mercurinium ions. All three cases involve a three-membered ring bearing a positive charge

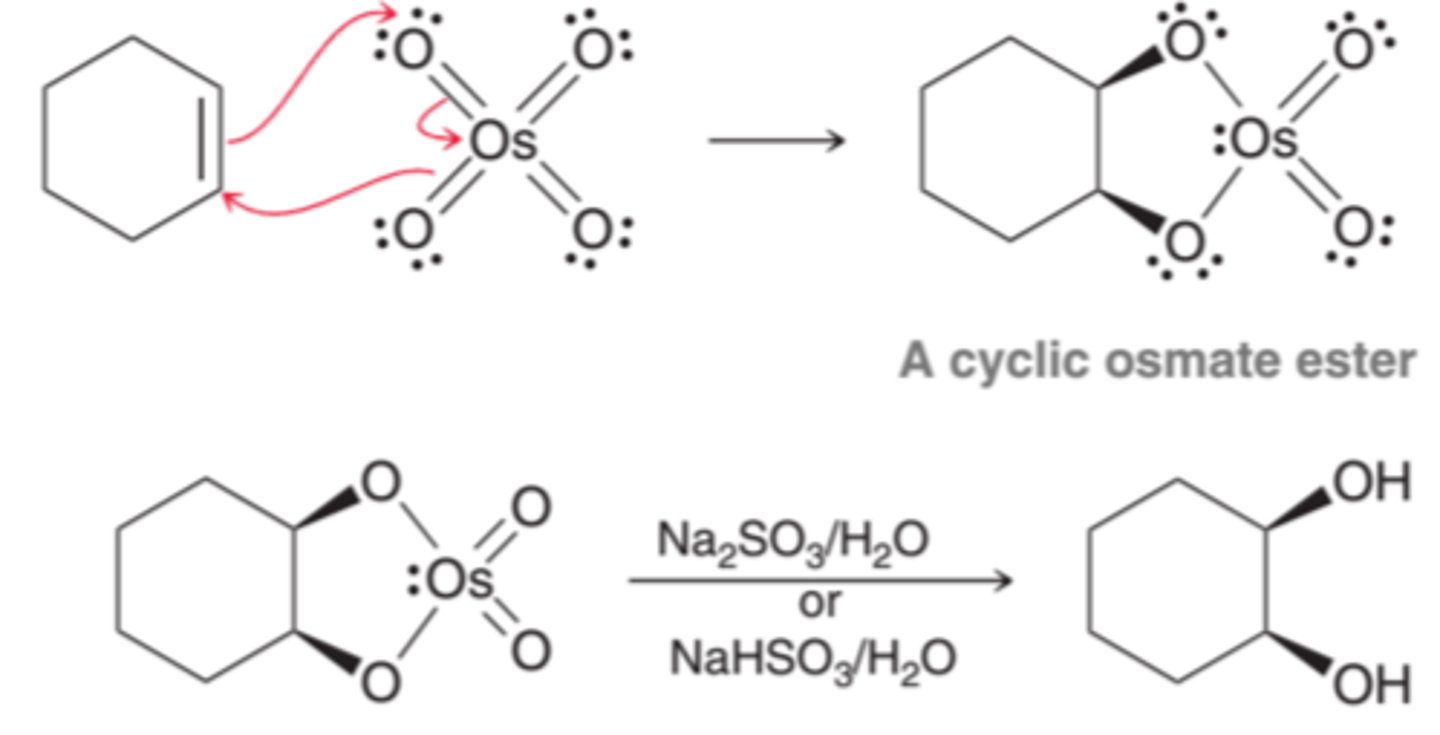

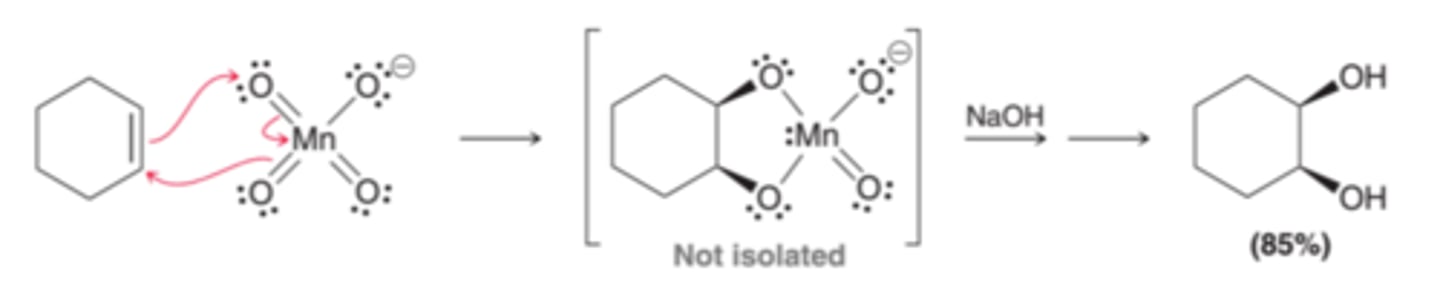

Syn Dihydroxylation

When an alkene is treated with osmium tetroxide(OsO4), a cyclic ester is produced. Osmium tetroxide adds across the alkene in a concerted process, so both oxygen atoms attack tot he alkene simultaneously. This effectively adds two groups across the same face of the alkene producing syn addition. The cyclic osmate ester that results can be isolated and then treated with either aqueous sodium sulfite(Na2SO3) or sodium bisulfite(NaHSO3) to produce a diol

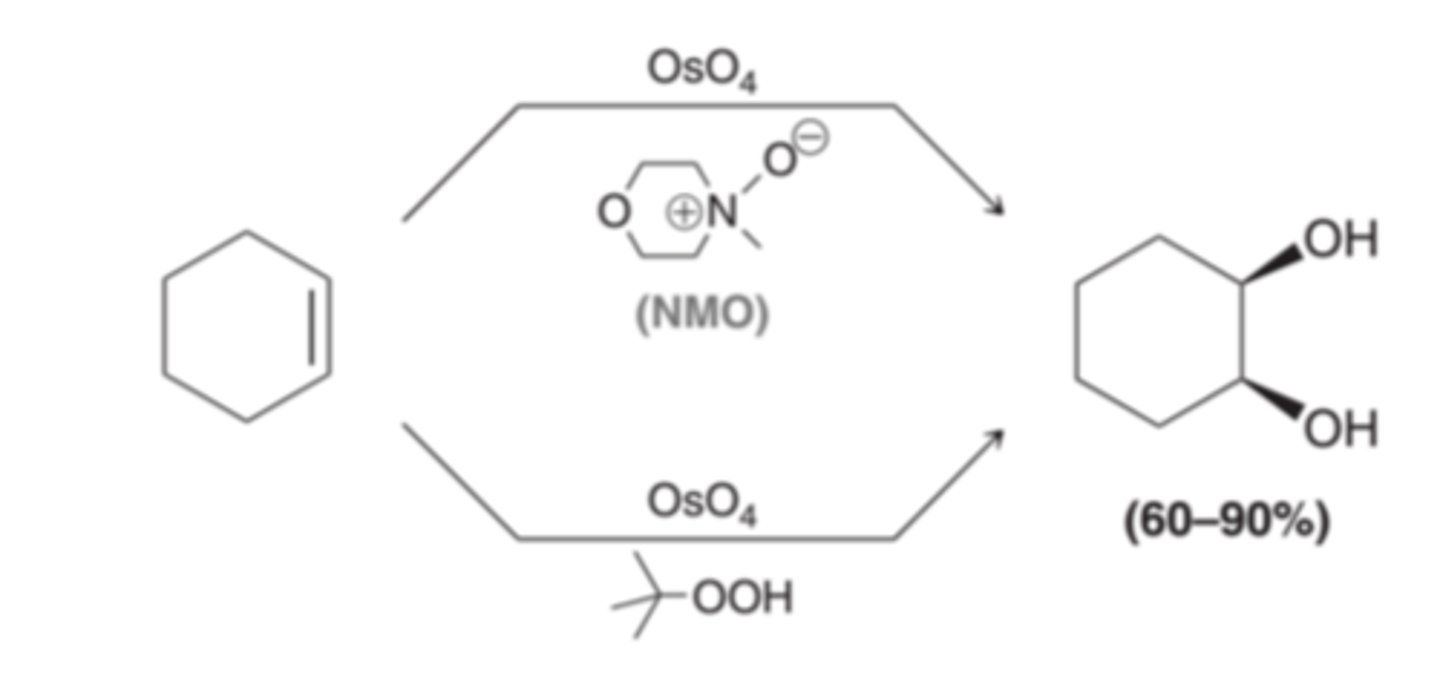

Co-Oxidants for OsO4

Co-Oxidants serve to regenerate OsO4 as it is consumed during the reaction so that OsO4 functions as a catalyst and even small quantities can produce large quantities of diol. Typical co-oxidants include N-methylmorpholine N-Oxide(NMO) and tert-butyl hydroperoxide

Different Mechanism for Achieving Syn Dihydroxylation

Involves the treatment of alkenes with cold potassium permanganate under basic conditions. This is a concerted process that adds both oxygen atoms simultaneously across the double bond

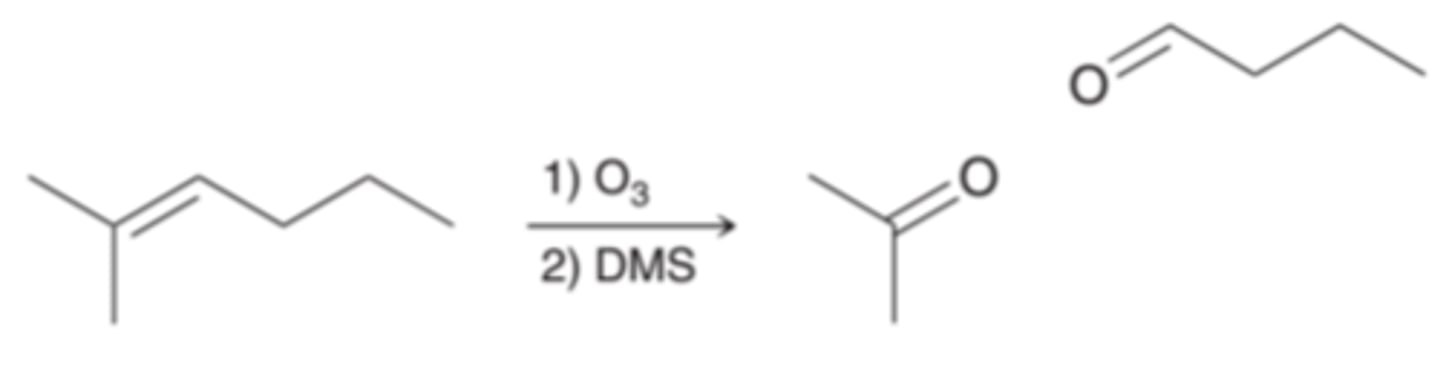

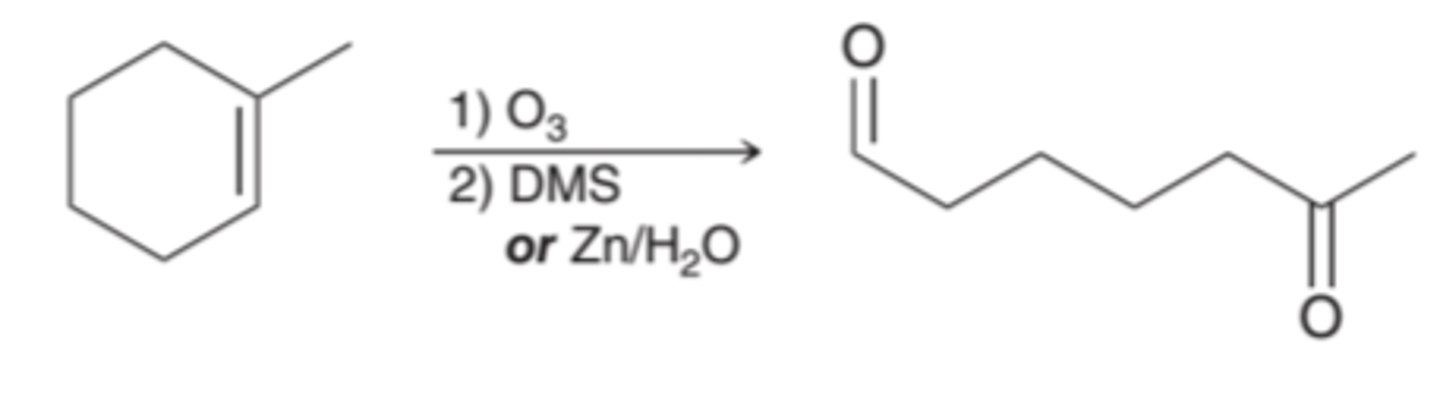

Oxidative Cleavage

Many reagents will add across an alkene and completely cleave the C=C bond. One such reaction is called ozonolysis in which the C=C bond is completely split apart to form two C=C double bonds. Therefore, the issues of stereochemistry and regiochemistry become irrelevant

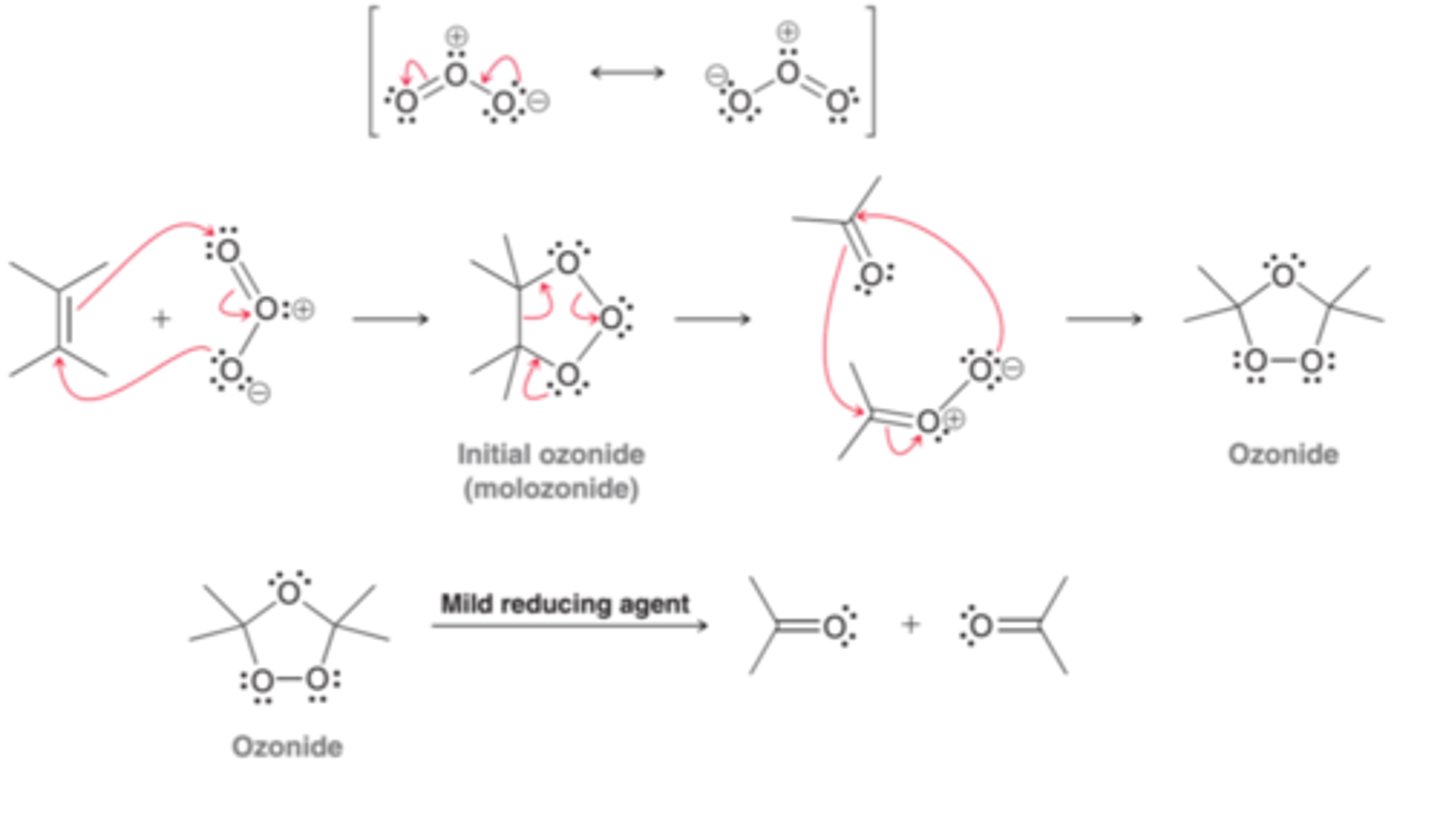

Ozone

A compound with the resonance structures shown in 1st example in image. Ozone will react with an alkene to produce an initial, primary ozonide(or molozonide), which undergoes rearrangment to produce a more stable ozonide(2nd example in image). When treated with a mild reducing agent, the ozonide is converted into products(3rd example in image).

Common Reducing Agents

Common examples of reducing agents include dimethyl sulfide (DMS) or Zn/H2O

Substitution Reactions and Syntheses Strategies

Substitution reactions convert one group into another

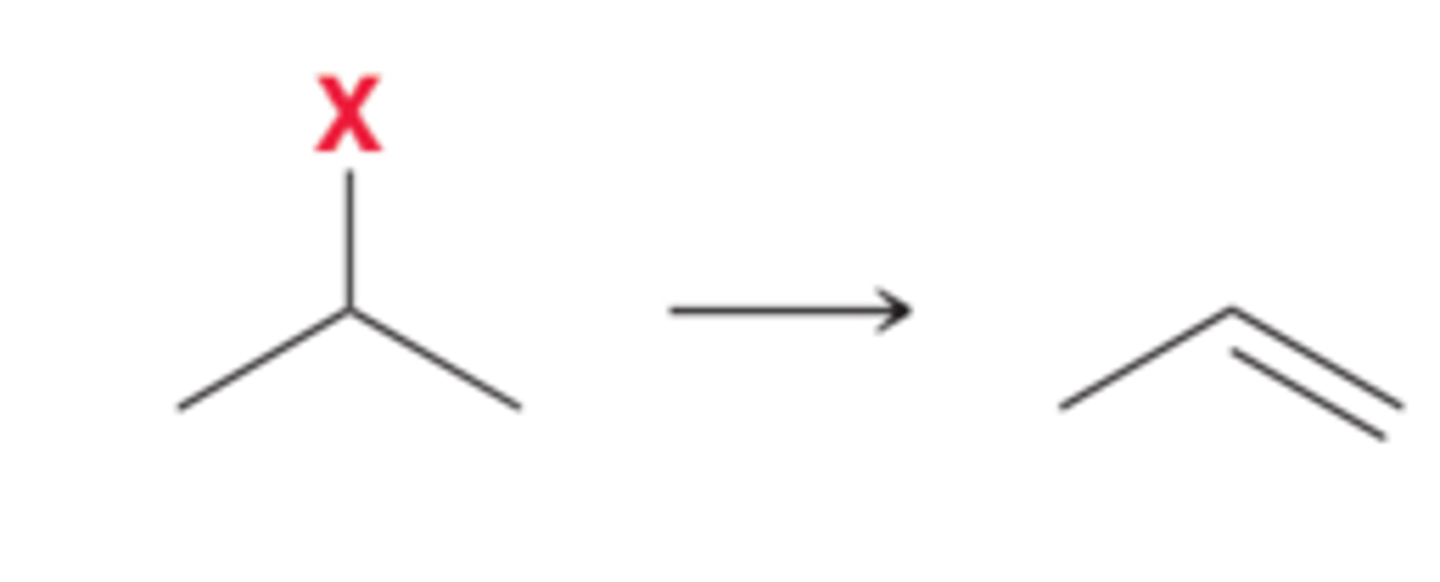

Elimination Reactions and Syntheses Strategies

Elimination reactions can be used to convert alkyl halides or alcohols into alkenes

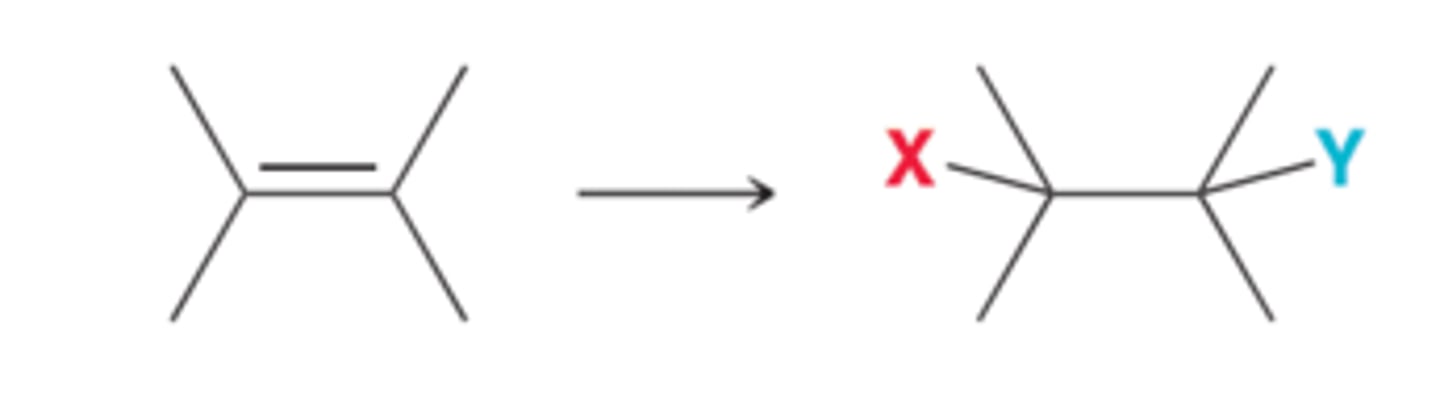

Addition Reactions and Syntheses Strategies

Addition reactions are characterized by two groups adding across a double bond

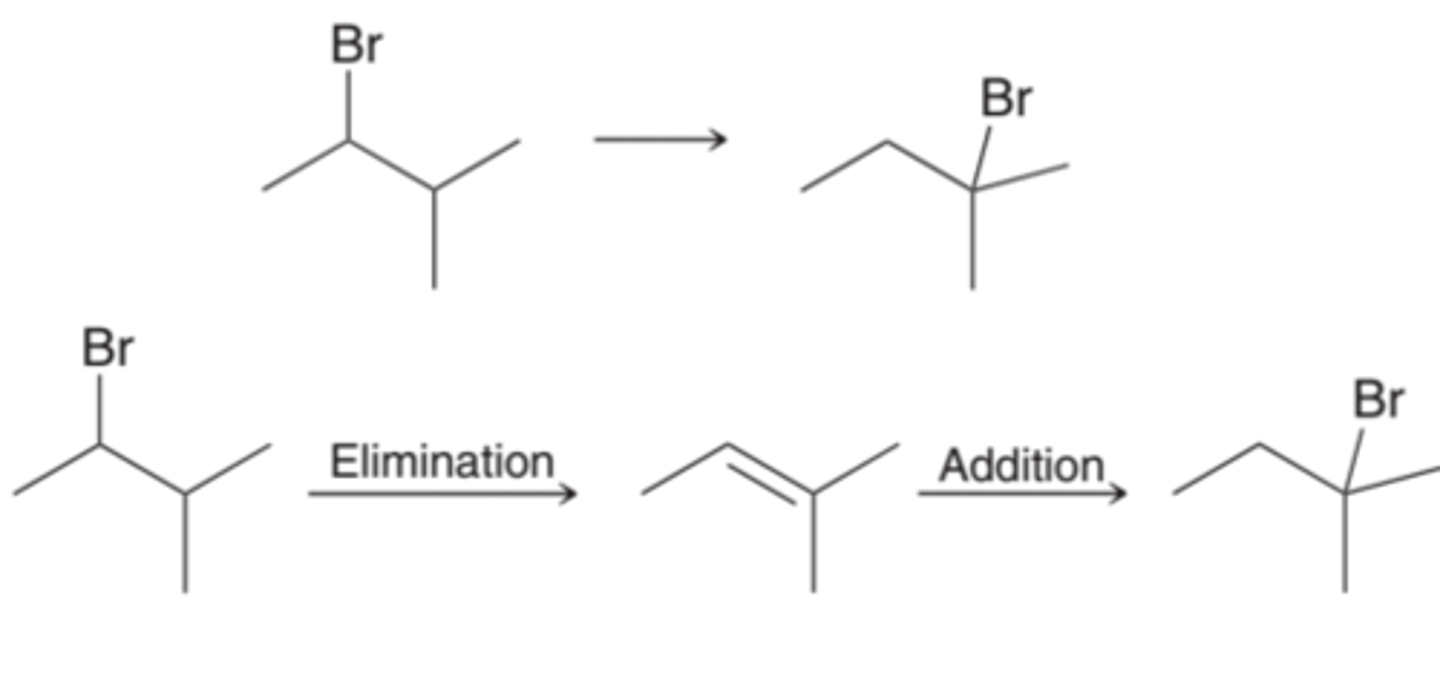

Changing the Position of a Leaving Group

For changing the position of a leaving group(1st example in image), two steps will be required: an elimination reaction followed by an addition reaction(2nd example in image).

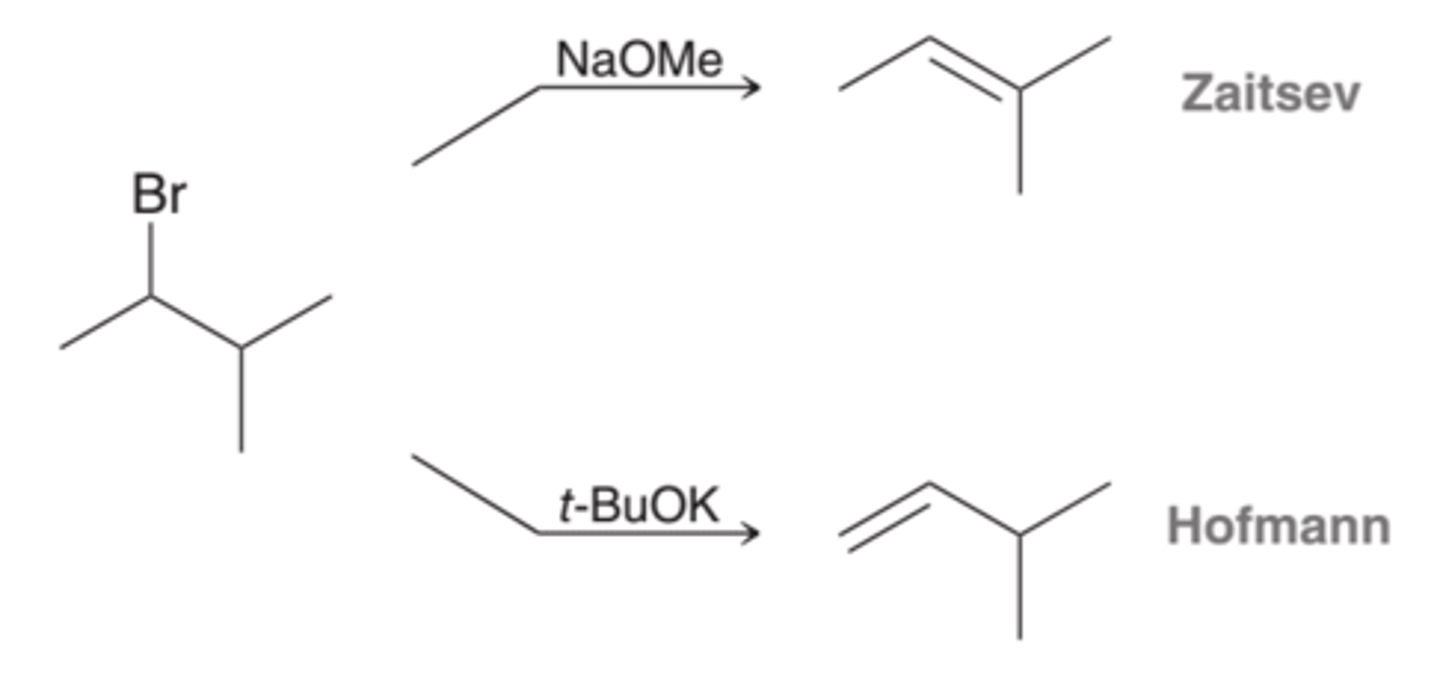

Regiochemical Considerations in Synthesis

When changing the position of the leaving group, the first step is elimination. With a strong base, such as sodium methoxide (NaOMe) or sodium ethoxide (NaOEt), the product is the more substituted alkene, the Zaitsev product. With a strong, sterically hindered base, such as potassium tert-butoxide (t-BuOK), the product is the less substituted alkene, the Hofmann product

OH as a Leaving Group

OH is a terrible leaving group. The OH group can be first converted into a tosylate by reacting it with TsCl in pyridine, which is a must better leaving group

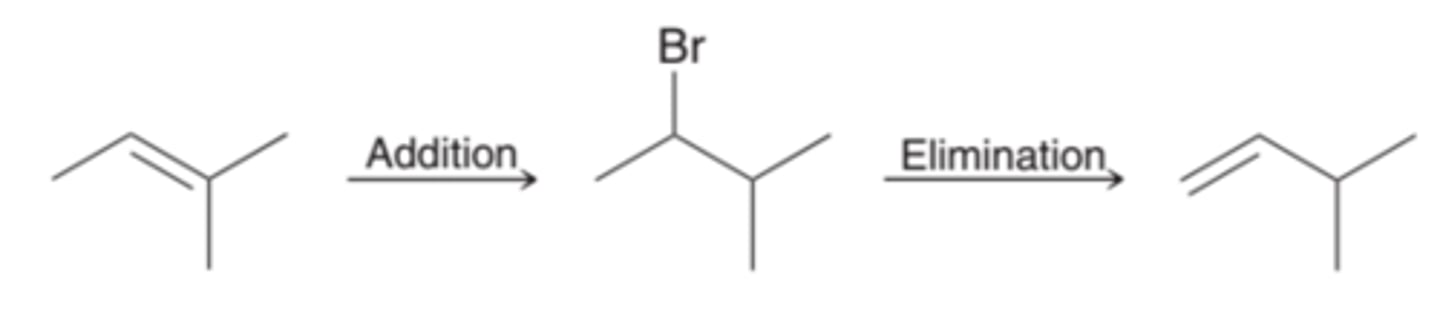

Changing the Position of the Pi Bond

To change the position of the Pi bond, addition and then elimination needs to take place. In the first step, addition, Markovnikov addition is achieved by using HBr, while anti-Markovnikov addition is achieved by using HBr with peroxides. In the second step, elimination, the Zaitsev product can be obtained by using a strong base, while the Hofmann product can be obtained by using a strong, sterically hindered base

Review of Reactions