Week 8 - Employment standards and wage regulation

1/35

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

36 Terms

Wage regulation and employment contracts

Wage regulation only applied to employees, if a worker does not meet the definition of an employee in the statute (such as an independent contractor), laws governing wages do not apply.

Wage regulation and occupation

Wage regulation can be excluded from an entire occupation (ex: lawyers or real estate agents), or to a specific job (ex: junior hockey player)

Some occupations may be entitled to higher or lower than the standard rates (ex: students under the age of 18 in alberta), and until recently, employees who serve alcohol on their jobs

Each Canadian jurisdiction has its own list of wage law exemptions

Employment standards laws usually fix a general minimum wage rate that applies to most employees and then list occupations that require rates different from the general rate

Employees earning a salary and not paid hourly (and not employed in an occupation excluded from the minimum wage) are also entitled to earn at least the minimum wage

3 types of wage regulation

Minimum wage legislation

Wage freeze or restraint legislation

Maximum wage legislation

Minimum wage legislation

Every canadian jurisdiction has a minimum wage that applied equally to both men and women

In history, minimum wage laws fixed womens wages at a lower level than mens wages on the assumption that men were supporting families and women were just earning “pin money”

Neoclassical perspective on minimum wage

This perspective claims that a statutory minimum wage causes unemployment by driving wages above market rates

Pro minimum wage camp

Relies on basic fairness and equity, and argue that

Minimum wage laws help the poor break the cycle of poverty

It reduces income inequality by increasing the disposable income of the working poor

Wage freeze of restraint legislation

A practice that holds wages at their existing level for a period of time, usually during economic crisis

Primarily used in the public sector (government workers, teachers, nurses)

Intended to control public spending and reduce budget defecits

Sometimes governments dont freeze wages outright, but limit e=increases to a fixed amount (Ex: 1% annually)

Wage freeze laws can override collective bargaining rights for unionized workers, leading to constitutional challenges (these are rare)

Governments rarely interfere in private sector wage negotiations, these freezes are usually the result of company policy or negotiation, not legislation

Maximum wage legislation

Limits how much the highest paid individuals (such as CEOs) can earn, particularly in relation to lower-paid workers in the same organization

Goal is to promote income equality

No laws currently mandate a maximum pay ratio between executives and employees in Canada

However, some Canadian governments have passed laws that regulate the compensation levels of executives of public sector corporations

Wage discrimination

Women with post-secondary education in canada earn 63% of what similarly educated men earn

Racialized employees earn (Men-78%, women 87%) of what their non-racialized counterpart earns

Workers with disabilities also earn considerably less than able-bodied workers

It is difficult to explain the gap because there are many variables involved

Women often have more career interruptions for caregiving responsibilities, they often negotiate less than men, gender stereotyping, and implicit gender discrimination

Regulating wage discrimination

Human rights statutes have long prohibited employers in Canada from discriminating in wages based on race, ethnicity, disability, gender, etc.

However, it is inadequate for addressing less obvious forms of wage discrimination, such as systematic discrimination

The human rights statutes are a complaint-based legislation, so it requires employees to learn their legal rights, file a complaint against their employer (which few do), and prove their lower pay rate is related to discrimination on a prohibited ground listed in the legislation

Equal pay laws (equal pay for the same job)

The most straightforward (and limited) model, targets gender-based, two-tier wage grids.

Comparable worth (equal pay for equal work laws)

Requiring equal pay for “substantially similar work”

Measured by: skill, effort, responsibility, and working conditions

Limited scope

Pay equity (equal pay for work of equal value laws)

Designed to tackle systemic wage discrimination in female dominated jobs

Explicit gender-based wage grids have been abolished in Canada by equal pay laws. However, the explanation for the persistence of a gender wage gap is far more complex than just blatant sexism. For Instance, economists have observed that women tend to “crowd” into relatively lower-paying jobs (ex: retail, sales, and other service sector jobs; clerical work; and childcare), and more often than men, they tend to select jobs that involve lower risk, less travel, and fewer working hours (all factors that tend to be associated with lower wages).

Pay equity enactment

The pay equity legislation in Canada requires an employer (and unions, where present) to take proactive steps to ensure equal pay for work of equal value, especially to address systemic wage discrimination in female-dominated job classes

Pay equity statutes allow for certain permissible wage differences, but such differences must be attributable to factors other than gender discrimination (such as seniority systems, merit pay systems, etc)

Pay equity enactment steps

Employer (or unions) must:

Identify the scope of the pay equity evaluation

Identify the “job classes” that will be used in the evaluation

Identify male-and-female-dominated job classes

Evaluate job classes

Compare evaluation scores and search for comparators

Prepare and post an equity pay plan

Make upward adjustments to achieve pay equity

Identifying the scope of the pay equity evaluation

The employer must first determine what units will be included in the pay equity evaluation (Ex: entire organization or department?)

Identifying the job classes that will be evaluated in pay equity

The employer divides the workplace to be evaluated into “job classes”

Job classes can include a variety of job titles, provided that the jobs included in the class are similar in terms of duties and required qualifications or fall within the same salary grade

Identifying male-and-female-dominated job classes in pay equity

Define what job classes are female dominated

In Ontario, the pay equity act defines a job class as female dominated if 60% or more employees in that class are female

Evaluating the job classes for pay equity

Once the workplace has been divided up into male-and-female-dominated job classes, use a gender neutral job evaluation system based on

Skill

Effort

Responsibility

Working conditions

They then assign point values to each of these factors for every job class

Aggregate scores are assigned, reflecting the overall value of the work performed

Comparing the evaluation scores and search for comparators in pay equity

The employer reviews the aggregate scores of male-and-female-dominated job classes to identify comparators (compares both job classes that have similar aggregate scores, and the male-dominate classes become the comparators)

Helps identify if equally valuable jobs (based on total scores) are being paid differently

Resolving pay equity disputes

A pay equity complaint must be heard by an expert tribunal (such as a human rights tribunal or specialized pay equity tribunal)

If either party is unhappy with the decision, they can seek judicial review by a court

Current state of pay gap

The gender wage gap continues to exist in the Canadian workplace.

Pay equity provides an example of how work law (legal signals and legal rules) have great difficulty changing deeply ingrained practices and norms

The extent to which wage laws achieve their objectives continues to be a matter of debate

Challenges with regulating hours of work

Regulating working time involves persistent challenges because it engages many competing interests:

Employers: Want flexibility and the ability to assign longer hours when needed, without incurring large labour costs

Employees: Want enough hours to earn a decent standard of living, but not so many hours where they get too little time for rest, sleep, and some fun

Governments: Are concerned with encouraging a distribution of available work among the population that produces optimal employment levels, including low unemployment rates

Regularing hours of work requires a sensible balance, which constitutes the biggest issues in the law of work

History of working time laws in Canada

Unions first bargained reduced hours, vacations, leaves, and paid holidays into their collective agreements, and eventually, governments enacted hours of work legislation

1919 was when the 8 hour workday was first formed, and BC was the first Canadian province to implement this

Statutes implemented in the Canada Labour Standards Code (1965)

Standards 40 hour workweek

8 hour workday

Mandatory overtime pay at a rate of 1.5 times the regular rate

8 statutory holidays

Periods of leave and gradual amendments to employment insurance laws

Unionized and non-unionized employees are entitled to these laws, however, unionized employees may have a collective agreement that provides more generous conditions

Justifications for working time regulation

Maximum hours of work laws are part of the governments pursuit to make the lives of working people safer and healthier

Governments have used working time regulation and overtime pay rules to fight unemployment

Working time regulation is a tool by which governments seek to balance competing social and economic values

Challenges of contemporary working time regulation

Shifting worker classifications: reclassifying workers from “employees” to “non-employees” (independent contractors, gig workers), this reclassification can exclude people from these legal protections

Rise in self employment: OCED study says 25% of the increase in income inequality since 1980s is linked to rise in self employment. These workers are not covered by most working time laws

Government approach to challenges of contemporary working time regulations

Governments could impose a strict cap on the number of hours employees could work per day or week, but they have generally avoided this

Instead, they have opted for flexibility, such as allowing averaging agreements (spreading work hours over multiple weeks), requiring written agreements for overtime exemptions, and providing employer-employee negotiated limits that are within the statutory maximums

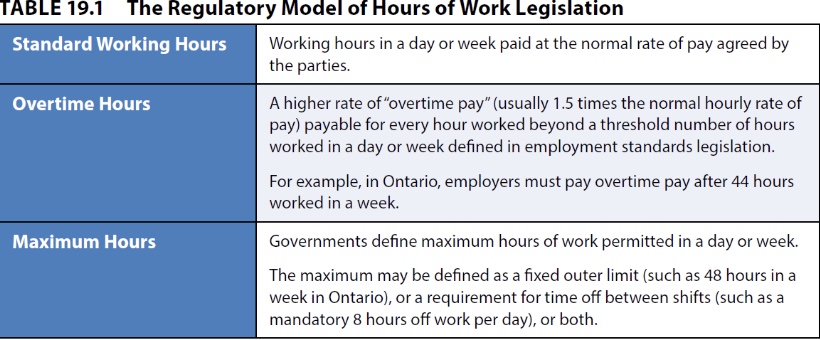

Principal models used in Canada to regulate hours of work

The regulatory model: requires employers to pay employees overtime pay after they have worked a certain number of hours

The averaging agreement method (not in QB, NL, or PEI): agreement to average out the number of hours worked over a longer period than the standard workweek

Regulatory model of hours in work legislation

Notes:

In NL, overtime is payable after 40 hours per week, and employees must be given at least 8 consecutive hours off per day and 24 hours off per week

Maximum hours of work rules may not apply in cases of emergencies, and in some cases, employers can apply for permits exempting them from some hours of work rules

Employment standards legislation sets minimums with exemptions, certain roles do not qualify for overtime, such as professionals (managers and supervisors, accountants, etc)

Should an employer pay for overtime hours worked, even if the employee did not get prior approval? (as long as the employer permitted or tolerated the work being done)

Yes, the employer generally must pay for overtime worked.

Courts and employment standards board focus on actual work being performed, not just policies.

Fresco v. Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC)

Fresco filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of 31,000 customer service employees employed by the CIBC alleging that CIBC’s policies relating to the tracking and payment of overtime pay led to systemic violations of the requirement in the Canada Labour Code to pay overtime pay for hours worked beyond 8 hours in a day or 40 hours in a week

The Code (s. 174) provides that overtime pay is owed at the rate of 1.5 times the regulated pay rate when the employer “requires or permits” the employee to work overtime hours. CIBC argued that its policies required employees to obtain managerial approval before working overtime and, therefore, overtime that was worked without approval was neither “required or permitted” by the employer.

CIBC’s policy requiring prior approval for overtime did violate the Canada Labour Code’s obligation to pay for overtime.

Requiring prior approval does not eliminate liability if the employer knows or ought to know the overtime is being worked.

If overtime is worked and tolerated, the employer has “permitted” it, even if it wasn’t formally approved.

The obligation to pay overtime under the Code is triggered by actual work, not internal policy rules.

Statutory holidays

All canadian jurisdictions designate a list of statutory holidays, employees must be given the day off work or be paid a premium rate

Note: legislation also requires employees be provided with a break

Statutory vacation time

The amount of time an employee is legally entitled to take off work during a year

In NL, this includes: New years day, good friday, canada day, labour day, remembrance day, and christmas day

Statutory vacation pay

The amount of pay a vacationing employee is legally entitled to receive while taking vacation time

In NL, it is 4% of gross wages if employed less than 15 years, and 6% of gross wages if employed 15+ years

Leaves of absence

Time away from work that an employee is legally entitled to take (paid or unpaid) without losing their position

Some leaves of absence recognized in some or all canadian jurisdictions include:

Parental leave

Family, medical, family caregiver, and critically ill child leaves.

Organ donor leave.

Bereavement leave.

Crime-related child death or disappearance leave.

Personal emergency leave.

Sick leave.

Reservist leave