Topic 6: Acids, Bases, and Buffers - Mastery

1/45

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

46 Terms

Salts and pH

When salts dissolve in water, their ions may react with water to produce solutions that are acidic, basic, or neutral, depending on the strength of the parent acid and base.

Neutral Salts

Formed when a strong acid (e.g., HCl, HBr, HClO4) and a strong base (e.g., NaOH, KOH) react. These salts produce neutral solutions because neither ion reacts with water as they are very weak (weak conjugate acids/bases).

Example: NaCl (s) → Na⁺ (aq) + Cl⁻ (aq)

Both Na⁺ and Cl⁻ are spectator ions that do not hydrolyze, so pH = 7.

Acidic Salts

Formed when a strong acid and a weak base react (e.g., NH₄Cl). The anion is the conjugate base of a strong acid, and thus a very weak base that does not affect the pH. The cation is the conjugate acid of a weak base and acts as a moderately strong acid

Example: NH₄⁺ (aq) + H₂O (l) ⇌ NH₃ (aq) + H₃O⁺ (aq)

The cation (NH₄⁺) hydrolyzes to produce H₃O⁺ ions, making the solution acidic.

pH of Acidic Salt Solutions

pH < 7 because the cation acts as a weak acid, generating additional hydronium ions.

Basic Salts

Formed when a weak acid and a strong base react (e.g., NaCH₃COO). The cation from the strong base does not affect the pH. However, the anion is the conjugate base of a weak acid and acts as a moderately strong base

Example: CH₃COO⁻ (aq) + H₂O (l) ⇌ CH₃COOH (aq) + OH⁻ (aq)

The anion (CH₃COO⁻) hydrolyzes to produce OH⁻ ions, making the solution basic.

pH of Basic Salt Solutions

pH > 7 because the anion acts as a weak base, generating hydroxide ions.

Salts of Weak Acid and Weak Base

Both the anion and the cation can undergo hydrolysis. The pH depends on the competition between the acid properties of the cation and the basic properties of the anion - depends on the relative Ka and Kb values of the ions.

Determining Salt Solution’s Nature

Compare Ka (of cation) and Kb (of anion):

If Ka > Kb → acidic

If Ka < Kb → basic

If Ka = Kb → neutral.

Hydrolysis Definition

Hydrolysis is the reaction of an ion in water (if it is a stronger acid or base than water) → causing it to donate or accept protons from water → to form H₃O⁺ or OH⁻ ions → affecting pH.

Buffer Solutions

Buffers resist changes in pH when small amounts of acid or base are added.

Composition of a Buffer

A buffer consists of a weak acid and its conjugate base, or a weak base and its conjugate acid, in roughly equal and substantial amounts.

Acid Buffer: CH₃COOH (aq) + CH₃COONa (aq)

Basic Buffer: NH₃ (aq) + NH₄Cl (aq)

Mechanism of Buffer Action

HA ⇌ H+ + A−

When H₃O⁺ is added, the conjugate base mops up the protons to neutralize it;

A− + H₃O+ → HA + H₂O

When OH⁻ is added, the weak acid donates protons to neutralize it;

OH− + HA → A− + H₂O

Buffer Capacity

The amount of strong acid or base that can be added before the buffer stops stabilizing the pH.

Buffers with higher concentrations of both the acid and base components have a larger buffer capacity

The ability of a buffer to resist pH change is greatest when [A⁻] ≈ [HA], i.e., when pH ≈ pKa.

Preparing a Buffer

Mixing a weak acid (e.g., acetic acid) with its conjugate base salt (e.g., sodium acetate).

Mixing a weak base (e.g., ammonia) with its conjugate acid salt (e.g., ammonium chloride).

Adding a strong base (e.g., NaOH) to a weak acid (e.g., acetic acid) to neutralize half of the weak acid.

Adding a strong acid (e.g., HCl) to a weak base (e.g., ammonia) to neutralize half of the weak base

Buffer Mechanism Example - Acetic Acid Buffer

Acetic Acid Buffer - CH₃COOH + CH₃COONa

CH₃COONa dissociates to give CH₃COO⁻, establishing equilibrium with CH₃COOH.

Adding a strong acid: Added H₃O⁺ is consumed by CH₃COO⁻ → CH₃COOH + H₂O, minimizing pH change.

Adding a strong base: Added OH⁻ reacts with CH₃COOH → CH₃COO⁻ + H₂O, again minimizing pH change.

Buffer Range

A buffer works best when the ratio [A−]/[HA] is close to 1

At Equal [A⁻] and [HA] → pH = pKa, because log(1) = 0.

Effective buffer range is typically pKa ± 1 pH unit.

To make a buffer at a desired pH, one must select an acid/base pair where the pKa is close to that target pH

![<ul><li><p><span><span>A buffer works best when the ratio [A−]/[HA] is close to 1</span></span></p></li></ul><ul><li><p>At Equal [A⁻] and [HA] → pH = pK<sub>a</sub>, because log(1) = 0.</p></li><li><p>Effective buffer range is typically pK<sub>a</sub> ± 1 pH unit.</p></li><li><p><span><span>To make a buffer at a desired pH, one must select an acid/base pair where the pK</span><sub><span>a</span></sub><span> is close to that target pH</span></span></p></li></ul><p></p>](https://knowt-user-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/000ae0d5-fc39-48b4-8ae8-25e83d3b3836.png)

Biological Buffers - Carbonic Acid-Bicarbonate Buffer in Blood

H₂CO₃ ⇌ H⁺ + HCO₃⁻

This system regulates blood pH around 7.4 by neutralizing excess acid or base.

Excess acid → HCO₃⁻ + H⁺ → H₂CO₃

Excess base → H₂CO₃ → H⁺ + HCO₃⁻.

Effect of Dilution on Buffers

Dilution changes both [HA] and [A⁻] equally, so pH remains nearly constant (slight shift due to water’s contribution).

Limitations of Buffers

If too much acid or base is added, buffer capacity is exceeded, and pH changes significantly.

Half-Equivalence Point

pH = pKa at this point because [A⁻] = [HA].

Titration

A quantitative technique in which a solution of known concentration (titrant) is added to a solution of unknown concentration (analyte) until the reaction is complete

Equivalence Point

The point during titration where the titrant has completely reacted with the analyte; stoichiometric amounts are present (moles of the acid = moles of the base), and no reactant is in excess.

Endpoint

The point during titration at which the indicator changes color; ideally coincides with the equivalence point (specifically, near it).

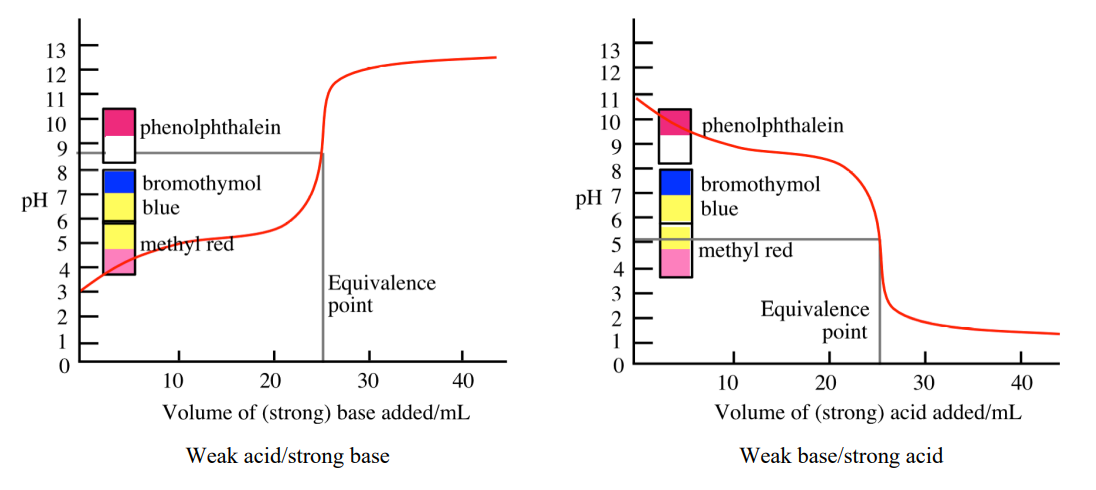

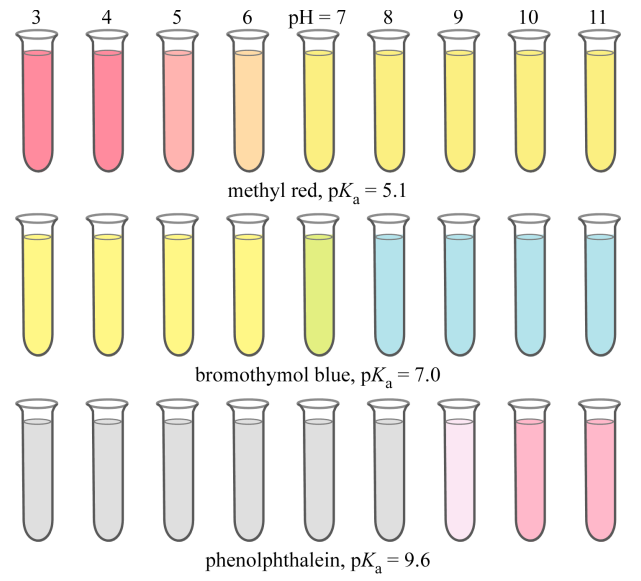

Indicator

A weak acid or base whose conjugate forms have different colors, used to signal the end of a titration.

Indicator Equation

HIn ⇌ In⁻ + H⁺; the ratio of the two forms determines the observed color

The acid form (HIn) and conjugate base form (In−) display different colors.

This color difference arises because the loss of H+ changes the molecular structure, altering the energy levels and thus the wavelengths of light absorbed

pH at Equivalence Point

Determines the best indicator;

During titration, you want the end point (when the indicator changes color) to coincide as closely as possible with the equivalence point (where moles of acid = moles of base).

Therefore, the indicator’s pKa should be close to the pH at the equivalence point.

pH at Half-Equivalence Point

Determines pKa of the weak acid or the conjugate acid of the weak base

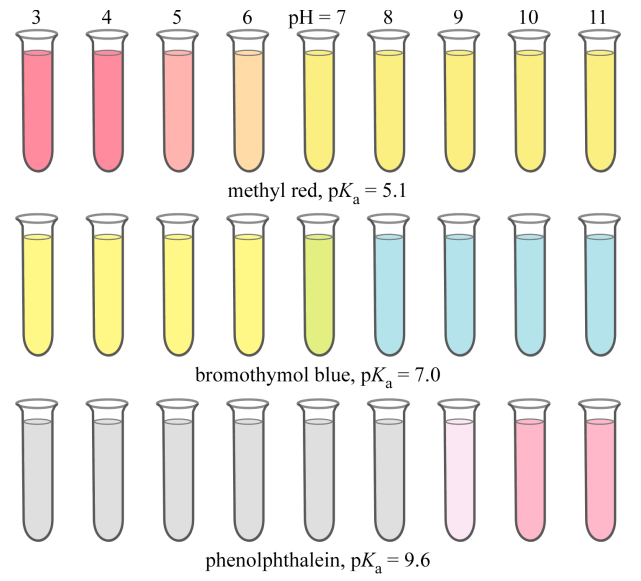

Titration Curve for Strong Acid + Strong Base

pH starts very low because of the strong acid, then at the equivalence point the pH = 7 because the salt formed (e.g., NaCl) does not hydrolyze

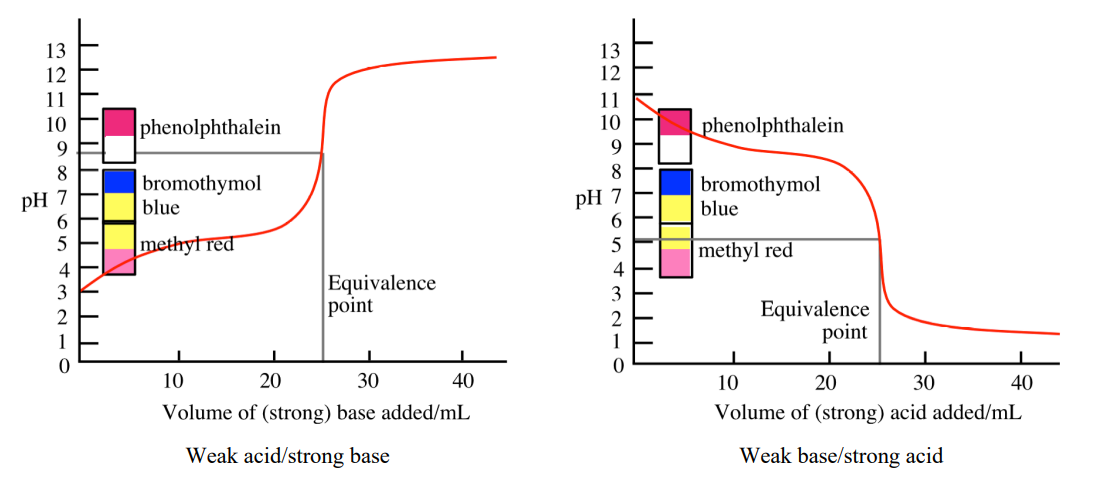

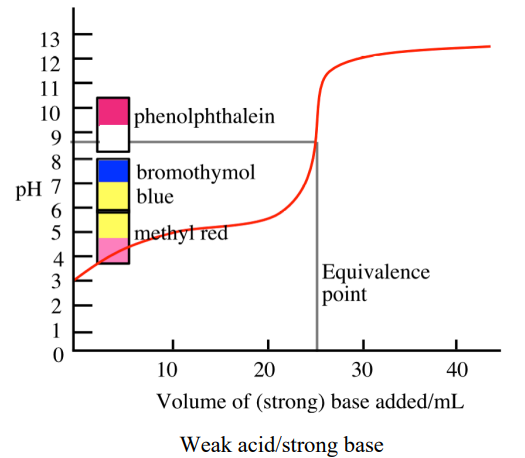

Titration Curve for Weak Acid + Strong Base

pH starts higher than a strong acid because the acid is only partially ionized, then at the equivalence point pH > 7 because the conjugate base (from the weak acid) hydrolyzes to produce OH⁻

Titration Curve for Weak Base + Strong Acid

pH starts high because the base solution is basic, then at the equivalence point pH < 7 because the conjugate acid hydrolyzes to produce H⁺

Buffer Region in the Titration Curve

A plateau in the titration curve where both the weak acid and its conjugate base are present, resisting pH change

Occurs before the equivalence point

Strong Acid + Weak Base Indicator Rule

Use indicator with color change in acidic region

Strong Base + Weak Acid Indicator Rule

Use indicator with color change in basic region

Half Equivalence Point (For Weak/Strong Acids/Bases)

The point at which half of the acid (or base) has been neutralized → so [HA] = [A⁻] or [B] = [BH⁺] → so pH = pKa or pOH = pKb (because from the H-H equation, where the concentrations of acid and conjugate base/base and conjugate acid are equal, it becomes log(1), which is 0)

pKa Determination Practical Use

Allows experimental measurement of weak acid or weak base strength

Titration Curve Interpretation

Inflection point corresponds to equivalence point; flat region indicates buffer zone

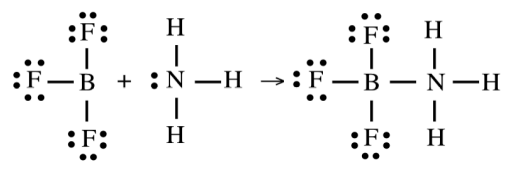

Lewis Definition of Acids and Bases

A broader definition proposed by Gilbert Lewis that classifies acids and bases based on electron pair transfer rather than proton transfer.

Lewis Acid

A substance that can accept a pair of electrons to form a bond (electron pair acceptor).

Examples: H⁺ (prototype Lewis acid), electron-deficient molecules like BF₃, and metal cations such as Co³⁺

Lewis Base

A substance that can donate a pair of electrons to form a bond (electron pair donor)

Examples: Ammonia (NH₃), amines, and ligands containing lone pairs of electrons.

Alternative Names for Lewis Acid

Also called an electrophile (“electron-loving”).

Alternative Names for Lewis Base

Also called a nucleophile (“positive charge loving”).

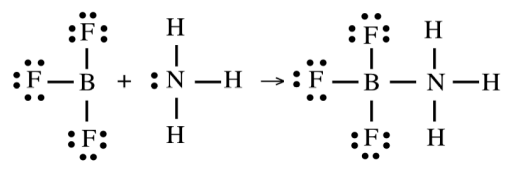

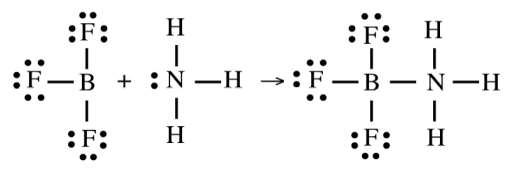

Mechanism of Lewis Acid–Base Reaction

Involves the formation of a coordinate covalent bond when the base donates an electron pair to the acid

Example: BF₃ (Lewis acid) reacts with NH₃ (Lewis base) to form a coordinate covalent adduct

BF₃ acts as the electron pair acceptor because boron is electron deficient

NH₃ acts as the electron pair donor through its lone pair on nitrogen.

BF₃·NH₃ is the product, where nitrogen donates an electron pair to boron, completing its octet

Product of a Lewis Acid–Base Reaction

An adduct — a compound formed by the combination of a Lewis acid and Lewis base via electron pair donation

Scope of Lewis Definition

Extends acid–base theory to reactions where no proton transfer occurs

Complex Ion Formation

A type of Lewis acid–base reaction where metal ions (Lewis acids) accept electron pairs from ligands (Lewis bases)

Example: Hydrated Cobalt Ion Reaction — [Co(H₂O)₆]³⁺ reacts with NH₃; Co³⁺ acts as Lewis acid by accepting electron pairs from ligands, and NH₃ or H₂O act as Lewis bases donating electron pairs to form coordinate bonds with the metal ion.

Significance of Lewis Theory

Provides a unified explanation for acid–base behavior in reactions without H⁺ or OH⁻ ions, including coordination and organic reactions.