cognitive; week 4; social attention

1/27

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced |

|---|

No study sessions yet.

28 Terms

Attention- top-down, bottom-up

top-down:

our goals dictate what we attend to

bottom up:

some types of information are automatically prioritised

usually: high-contrast (salient information)

however: social information is also automatically prioritised

Social attention

attending to social information in our environment

Social attention: In regards to information, we are predisposed to:

interpreting information as social information

finding faces in patterns

biological motion point light displays

looking to social information in our environment

attending to other people - their bodies, arms, legs, faces

preferentially attend to body parts that give information regarding intentions

Methods to study social attention

behavioural measures

eye-tracking

EEG

fMRI

more

Eye movements and trackers recap

Saccade: an eye movement

We can make 3-5 eye movements per second

We make many more tiny movements – micro-saccades

The earliest eye-trackers were built in late 1800s

Modern eye trackers can be either desktop or mobile

Software records saccades, microsaccades, fixations, pupil dilation …

The importance of social cues

interacting with other people is crucial to development

social cues help us learn key social skills

evolutionary perspective:

interpreting social partner’s behaviour & understanding social scenarios assist integration into a social group

The importance of our eyes

eyes give us an insight into what our social partners are paying attention to and helps us understand their thought processes

evolved to communicate

eyes both receive AND send information

Social attention- Developmental approach

within the first week of life, babies direct their attention to the eyes in a face

we can follow gaze by 3 months

by the time they reach 12 months they can orient their attention to the location of a gaze

joint attention

communicates attention and desires

alerts us to important aspects of the environment

facilitates language acquisition

pre-cursor to ToM development

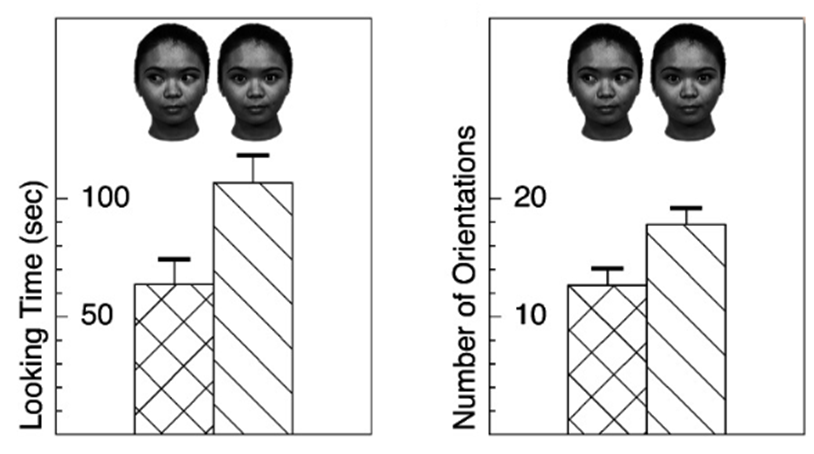

Sensitivity to gaze infants

are new-born babies sensitive to eye gaze?

17 new-born infants (24h-120h old)- direct gaze Vs averted gaze

Gaze cueing

when we see someone move their gaze, we move our own gaze so that we are both looking at the same location.

this is gaze cueing

This can happen automatically

has traditionally been investigated using cueing paradigms

Cueing paradigms- Posner (1980)

originally used by Posner (1980)

often called ‘posner-type cueing paradigms’

adapted to investigate gaze cueing

These paradigms show that participants are:

Significantly faster to detect a target when it is in same the location shown by the gaze cue (Valid Trials)

Slower to detect a target when it is in a different location to that indicated by the gaze cue (Invalid Trials)

Even when participants know the gaze won’t predict where the target will appear

Why does this happen?

When we see the gaze cue we move our own eyes in the same direction. So we’re faster to find targets that then appear in that location We have to move our eyes away from where the gaze is looking to find the target in a different location

What are the real world implications of social attention and gaze cueing? (NOT examples)

direct our attention to important information within our environment

helps us to plan our own actions

gives us an insight into other people’s intentions

reciprocal eye contact and attention to social information allows us to fit in as a member of a social group

EEG

measures electrical signals generated by the brain through electrodes placed at the scalp

an ERP is the electrophysiological response to a stimulus

specific ERPs are associated with certain stimuli

N170 associated with faces

N170 much greater amplitude to faces than to other stimuli

N170 larger and delayed for inverted faces, potentially reflecting “additional effort” by the face-processing neurons

N170 present for animal faces, with no inversion effect. Animal face stimuli are processed as faces. We still treat them differently.

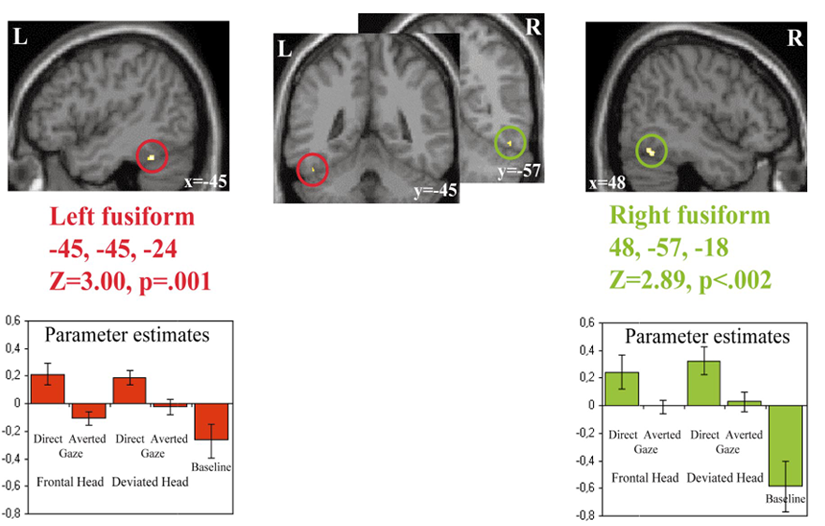

Insights from fMRI

not just one single brain region implicated in social attention, many regions:

Parts of the attention network, including areas implicated in goal-directed and exogenous attention (pSTS, SPL, FEF)

Areas responsible for coding gaze direction (aSTS), eye contact and emotional responses to gaze (amygdala/hippocampus)

Areas involved with facial identify recognition (fusiform gyrus)

Areas involved in theory of mind processing (medial prefrontal cortex, pSTS, TPJ)

Greater activation in fusiform gyrus ‘Fusiform face area’ to direct vs averted gaze

The directed gaze resulted in more activity in both sides of the fusiform than the averted gaze and for the baseline.

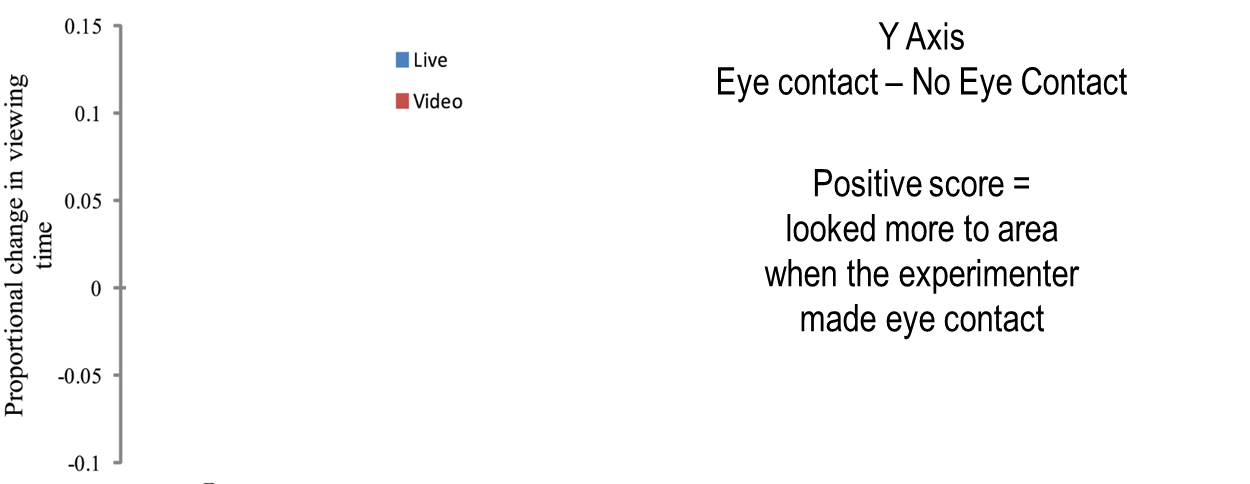

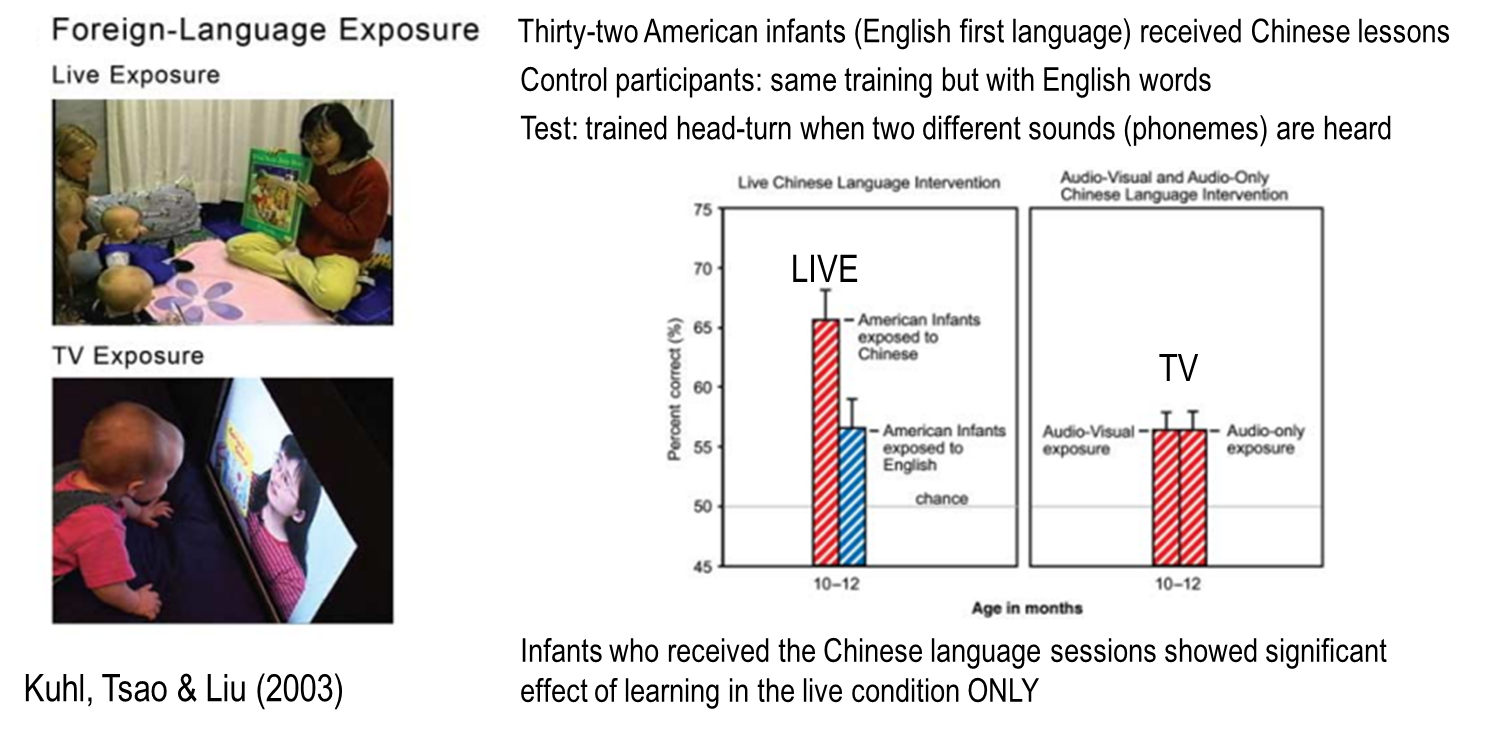

Social cognition research must consider the situation

live Vs video

direct Vs averted gaze

different stages of conversation

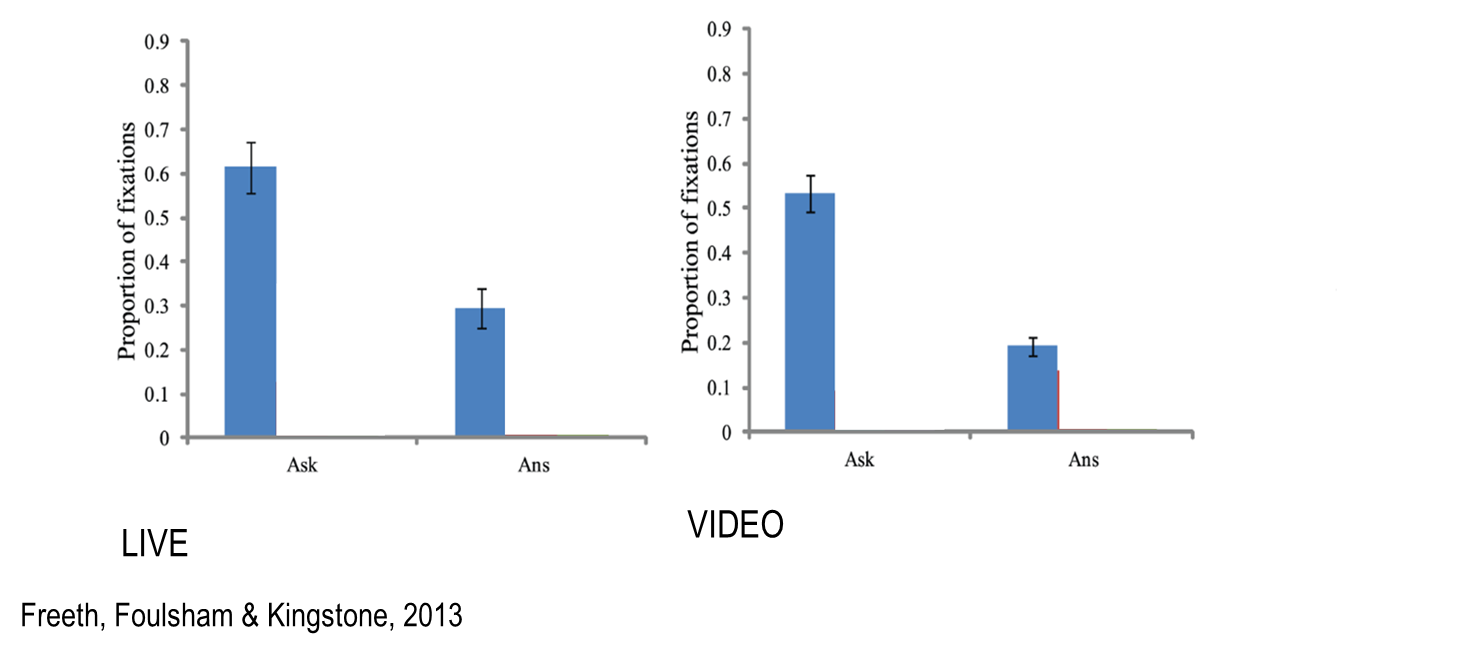

Experimenter eye contact- Freeth et al (2013)

There was more eye contact made by pp in live than video, because of social conversation aspects

Stages of conversation

Live:

Measured what happened when the person is giving an answer Vs asking a question. Having the space to avert your eyes, lowers the cognitive load to allow you to use more cognition to reply.

In a conversation, reducing cognitive load by averting gaze.

Turn taking:

direct gaze indicates listening to our social partners

averted gaze indicates we haven’t finished speaking

Social norms

‘look at me when I’m talking to you’

Video:

still in a conversation pps were more likely to avert gaze from the stimuli on screen when answering

Developmental approach: live Vs video

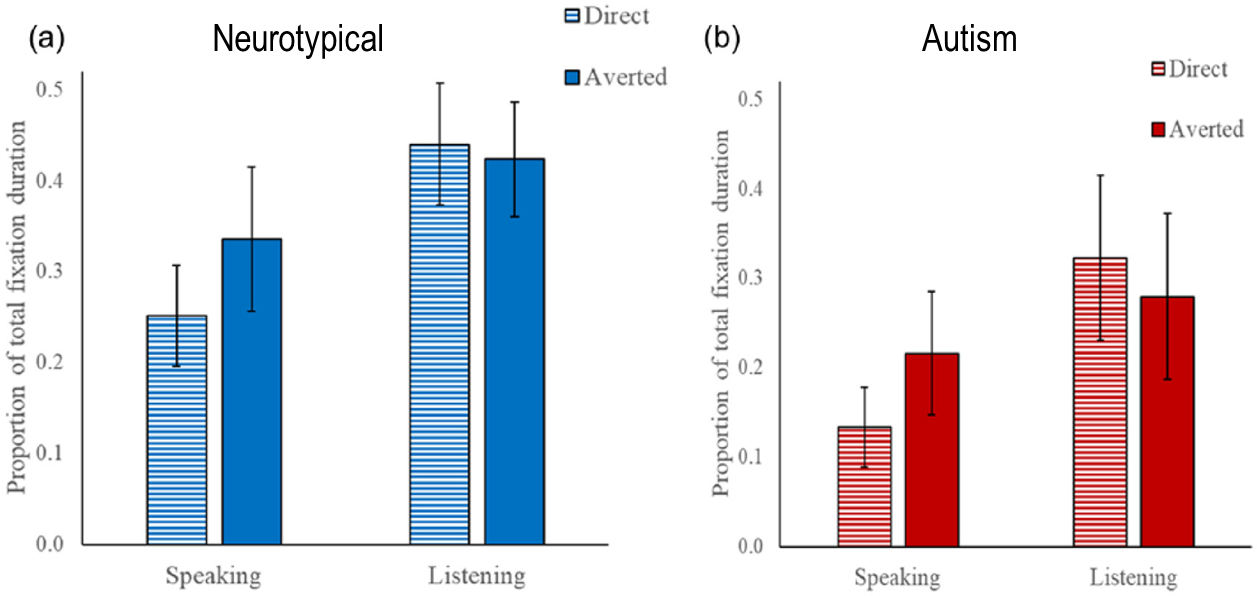

Neurodivergence and social attention

face fixations

fixation on experimenter’s eyes

stimulus type matters

59 autistic children; 22 neurotypical children

research question: can eye movements predict diagnostic classification?

measure: total fixation duration to faces

clear differences to the interaction stimuli only

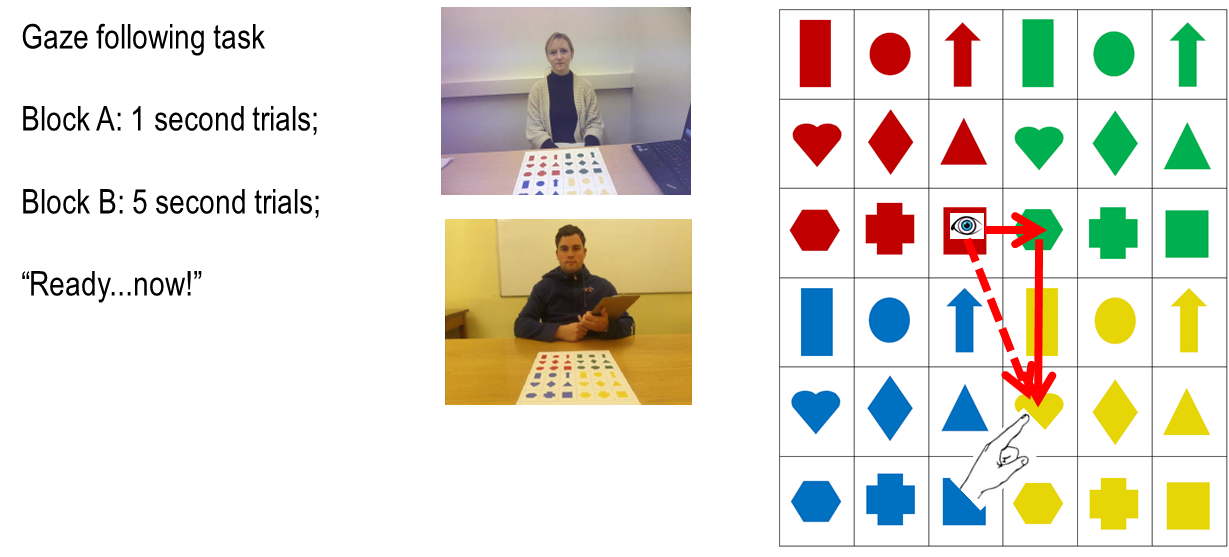

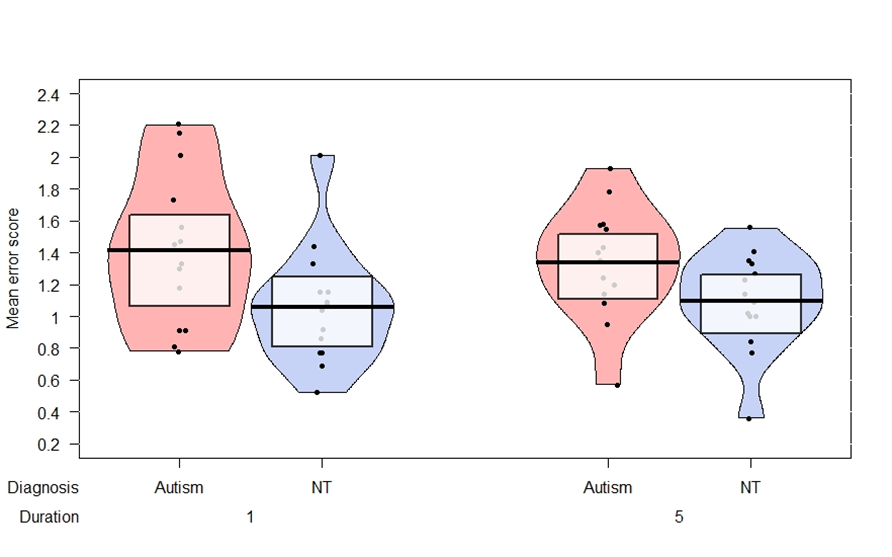

Studying gaze following in the real world

results: autistic adults Vs neurotypicals

Reading- Gaze cueing paradigms:

evolutionary psychology perspective:

gaze following is important for trans-generational learning.

Many vertebrates follow gaze.

primates follow the gaze of experimenters and other primates

chimpanzees follow the gaze of others to appropriate objects in their environment.

Social attention may be essential for the development of social cognition.

Thus, shifting attention in the direction of where another is looking distinguishes primates and humans from other animals.

Reading- Typical gaze cueing experiment

In a typical gaze cueing experiment in humans, a face stimulus is presented in the center of the computer screen. The face is usually first portrayed with direct gaze (or closed eyes), followed by averted gaze to the left or to the right, implying eye movements. Subsequently, a target object (e.g., a letter) is presented at one of the two lateral locations, and participants’ reaction time for detecting (or identifying) the target is measured. Time and again findings have yielded faster reaction times when targets appeared at locations that were spatially congruent with the averted gaze compared to when targets appeared at locations that were spatially incongruent with the averted gaze. These gaze cueing effects have been shown to persist up to 3 minutes

Gaze cueing effects: not using a face

Research has demonstrated that a variety of stimuli elicit such facilitation effects as long as they resemble faces. Indeed, gaze cueing effects have been replicated with a variety of face stimuli including photographs of faces, computerized faces, virtual agents, and even schematic drawings.

Even when participants were instructed that the shift in gazing behaviour is counter predictive of where the target will appear, they continued to shift their attention in accord with the direction of gaze.

Moreover, task instructions leading participants to perceive an ambiguous stimulus as a face increased cueing effects, and perceiving an ambiguous stimulus as a face was associated with distinct brain activations in neuroimaging studies. Thus, gaze cueing paradigms provided first evidence for people shifting their attention in accord with the visual system of others. Specifically, these studies seem to suggest that social attention depends on perceiving the central stimulus as a social entity (i.e., a face)

Social identity and gaze cueing

Social psychology has generated a substantial list of stimulus characteristics that influence gaze cueing effects.

masculine looking faces lead to greater gaze cueing effects.

Gaze cueing effects increase for high-status faces.

Faces that resemble the onlooker elicit stronger gaze cueing effects

Ingroup membership and shared political partisanship increase gaze cueing effects.

Taken together, these studies suggest that onlookers’ social attention appears most influenced by target faces that are highly relevant, target faces that might share common goals (e.g., ingroup members) or common opinions (e.g., party members), and target faces that portray important information about the environment.

Reading- Social attention in real-life situations

When people interact, they bring together their personal values, cultural heritage, and social norms. Socially shared knowledge structures, such as social norms, inform the actor when it is permissible to attend to another person, when it is inappropriate to attend to another person, and when it is actually a social requirement to pay attention to another person in order to acknowledge an ongoing interaction or communication. Researchers found that social attention changes in situations with potential for social interactions, compared to the isolated experimental conditions during a laboratory study.

Foulsham, Walker, and Kingstone (2011)

Foulsham, Walker, and Kingstone (2011) measured the social attention of participants who walked across campus and of participants who watched the video recording of walking across campus from a first-person perspective.

Participants watching the videos were more likely to attend to people passing by compared the real-life situation.

Laidlaw et al (2011) found that participants sitting in a waiting room attended to prerecorded videos of a confederate for longer periods than they did to a confederate who was actually sitting there in person.

Presumably, when encountering people in real life, where people can capture each other’s social attention, it sometimes is more appropriate to not attend to others.

Making participants believe they may be watched by wearing an eye tracker changes looking behaviour dramatically. The potential to interact with others in real life also influences the extent that people follow each other’s attention to objects.

Gallup et al. (2012) showed that pedestrians in public environments actively followed the attention of groups of confederates. This increased with the number of confederates looking toward the stimulus before saturating for large groups.

Gallup et al (2012) positioned an attractive stimulus in a trafficked corridor and measured whether people would look at it. A hidden camera recorded the extent 2,882 pedestrians followed other’s attention to the attractive stimulus. Passersby were more likely to follow the head turns of people walking in front of them, who thus could not see where they were looking, and less likely to follow the head turns of people walking toward them, who thus could see where they were looking. This supports the idea that social norms can influence how people overtly change their social attention when others can see them. It seems less appropriate to overtly follow the attention of a person when they can observe such signals of social interest.

Freeth et al (2013)

Freeth et al (2013) found that when being interviewed, interviewees looked more to the face and less to the background in the live condition, where the interviewer was physically present, compared to the video condition, where the interviewer was depicted in a video clip.

D. W.-L. Wu, Bischof, and Kingstone (2013)

A situation where people increase attention to their interaction partner is when they share a meal. When eating with a person compared to eating alone, participants’ attention was more drawn away from the surrounding objects to the person in front of them. This effect was amplified among pairs who talked more to each other during the meal.

One explanation is that people are especially keen to signal their engagement in the interaction and social interest in the other person.

Depending on the situation, social norms can reduce social attention or increase social attention to other people. Interestingly, reducing and increasing attention both are strong signals that individuals comply with social norms that regulate how much social interest is deemed appropriate in a situation.