Regional Anesthesia - Part 1

1/40

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

41 Terms

Q: What is Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS)?

The use of portable ultrasound by clinicians to guide procedures or assist in diagnosis at the patient’s bedside.

What are the main benefits and limitations of POCUS?

Benefits:

Improves safety and efficacy of regional anesthesia and vascular access;

provides fast, safe, effective, and low‑cost diagnostic support; improves outcomes and reduces costs.

Limitation: Does not replace a formal radiologic examination and must be interpreted within the full clinical context.

Airway, lung, gastric and abdominal evaluations

Guidance of regional and neuraxial techniques

Transthoracic Echocardiography (TTE)

Guidance of central and peripheral vascular access

TTE stands for Transthoracic Echocardiography.

A noninvasive chest-wall ultrasound that visualizes the heart’s structure and function in real time.

Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE)

Arterial Access

Key contrast (exam favorite)

TTE = Noninvasive, probe on chest wall

TEE = Semi‑invasive, probe in esophagus, better image quality but less immediate

Bladder Scan

» Pain Management (Acute & Chronic)

Airway Management

Urgent decompression of cardiac tamponade

Pain Management (Acute & Chronic)

Needle decompression for pneumothorax

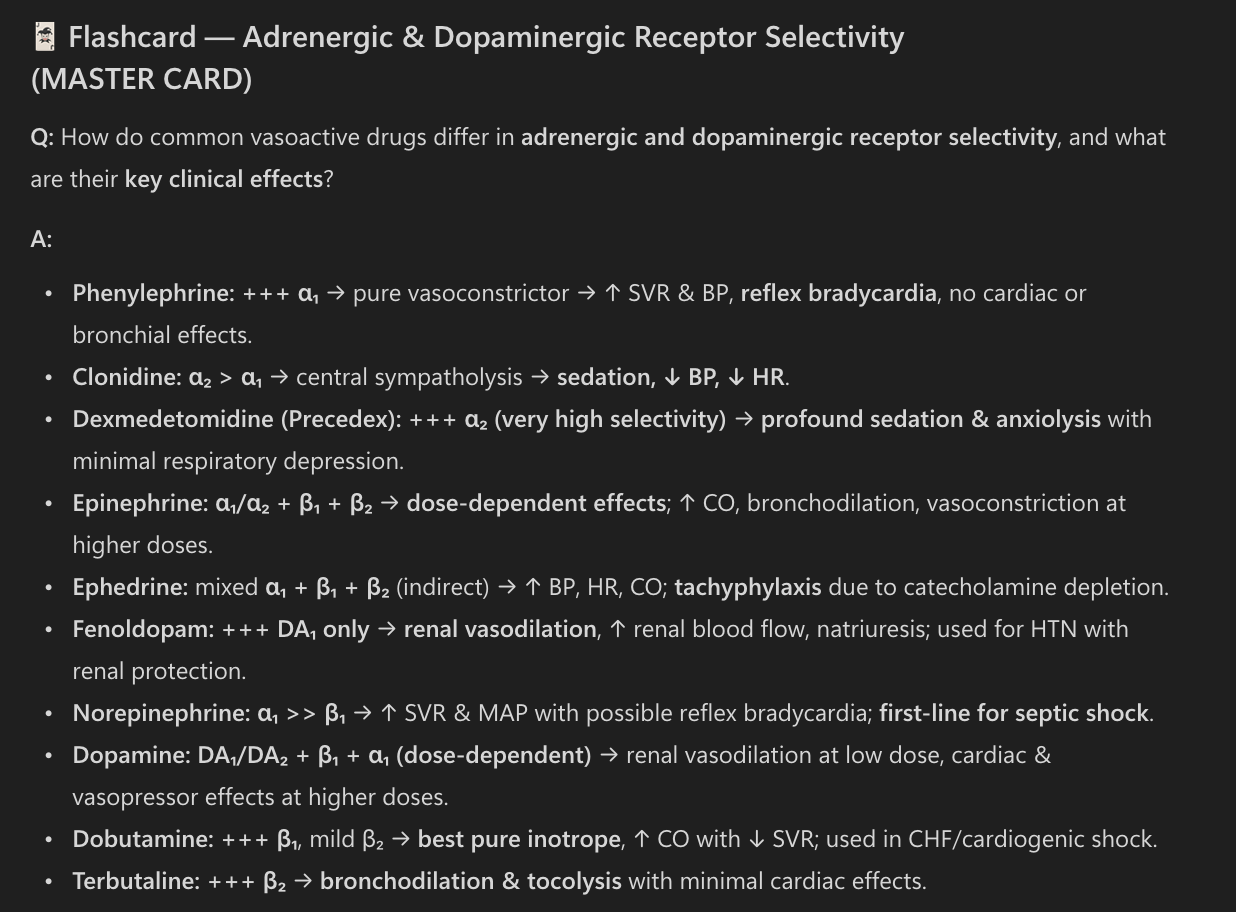

Limitations of POCUS

Facility‑specific: Lack of time and training, high cost of training/equipment, variable equipment quality, credentialing requirements

Staff‑specific: Missed or incorrect diagnoses, difficulty managing unexpected findings, poor image quality due to limited practice, lack of knowledge of artifacts and limitations

Patient‑specific: Difficulty obtaining images perioperatively (e.g., obesity, pregnancy, surgical draping)

Reimbursement‑specific: Incomplete or improper documentation limiting coding, billing, and compensation

Discipline‑specific: Lack of POCUS‑trained faculty, lack of universal standards and terminology, insufficient curriculum standards, lack of validated assessment tools, limited fellowship opportunities

AANA Position on the Use of POCUS

POCUS is a safe, fast, effective, and relatively cost-efficient modality, but its use requires specific training, ongoing education, experience, and a quality assurance program.

CRNAs are well positioned to use POCUS to guide patient care, including: 1. Regional anesthesia and 2. Multimodal pain management, 3. helping reduce or eliminate opioid use and 4. support faster recovery.

The incorporation of regional techniques for preventive analgesia is associated with:

Reduced postoperative pain

Reduced or eliminated opioid use

Decreased incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV)

Faster recovery

Shorter length of stay in the post‑anesthesia care unit (PACU)

Shorter time to hospital discharge

Increased patient satisfaction

Reduced incidence of postsurgical pain 3 to 12 months after surgery, decreasing the risk of prolonged opioid use

Regional anesthesia may have a positive long‑term impact on wound healing and immune function

Surgeries with a Higher Incidence of Chronic Pain:

■ Limb amputation

■ Thoracotomy

■ Inguinal herniorrhaphy

■ Abdominal hysterectomy

■ Saphenous vein stripping

■ Open cholecystectomy

■ Nephrectomy

■ Mastectomy

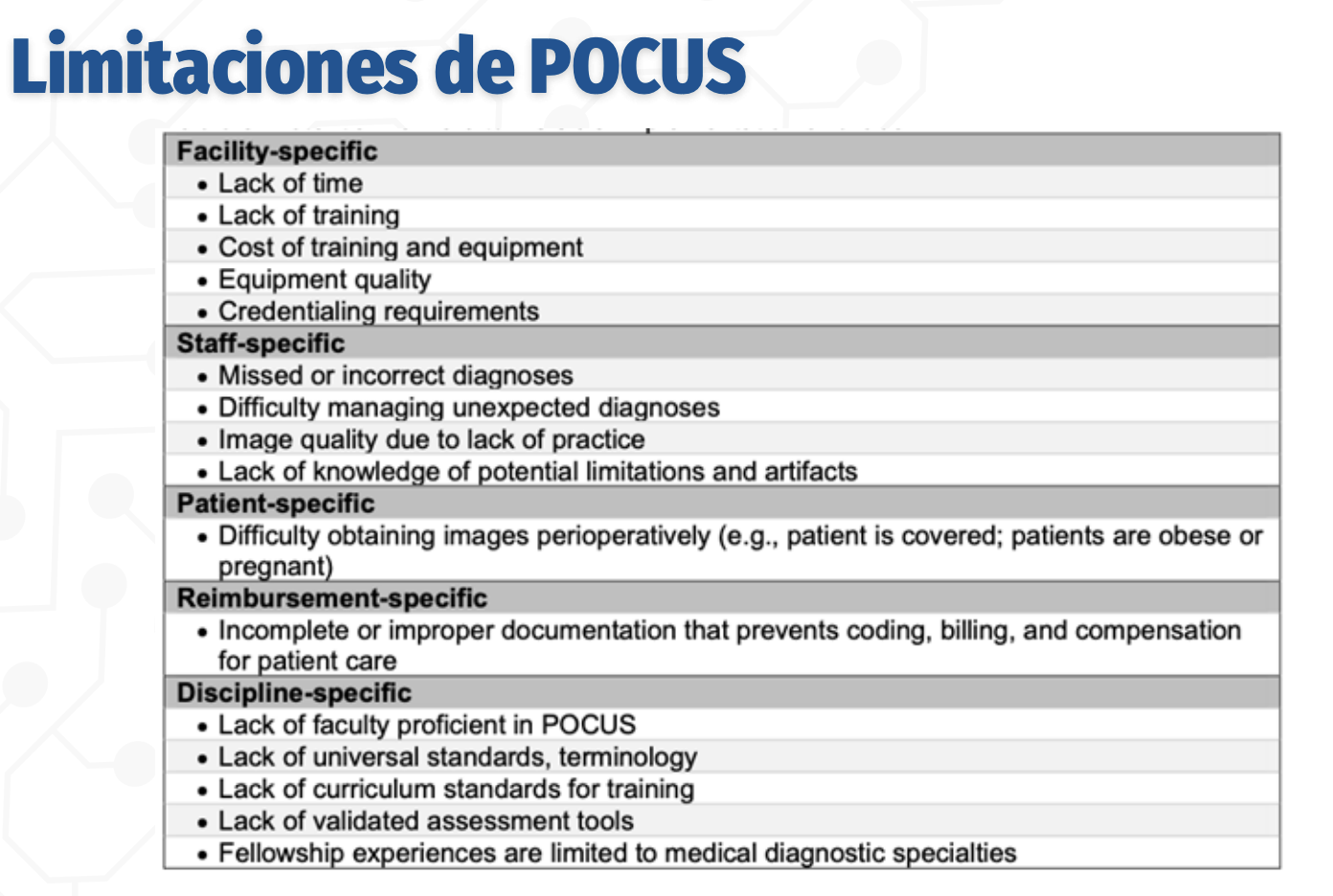

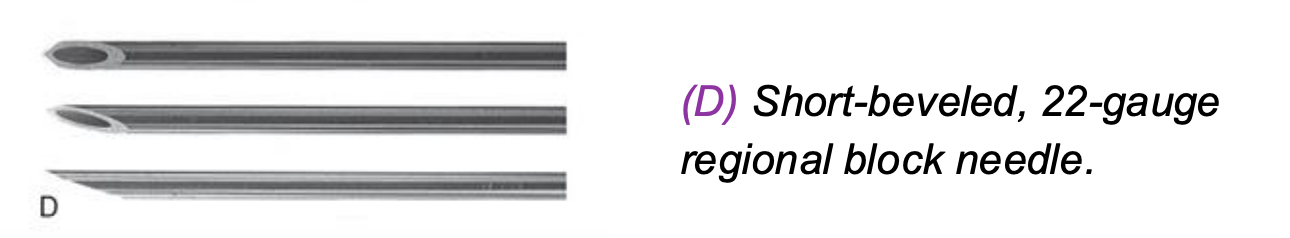

Blunt‑Beveled 25‑Gauge Needle

Used commonly for axillary brachial plexus blocks

Blunt bevel reduces the risk of nerve penetration and intraneural injection

Smaller gauge (25G) → less tissue trauma and patient discomfort

Tactile resistance helps identify tissue planes

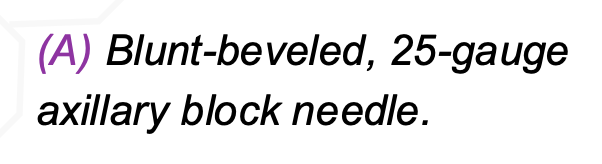

Long-beveled, 25-gauge (“hypodermic”) block needle.

Sharp, long bevel facilitates easy tissue penetration

Historically used for peripheral nerve blocks

Higher risk of nerve injury compared to short or blunt bevels

Less commonly used today due to safety concern

22‑Gauge Ultrasonography “Imaging” Needle

Designed for ultrasound‑guided regional anesthesia

Echogenic coating or textured surface → improved needle visibility

Balance between rigidity and flexibility

Enhances accuracy and safety during nerve blocks

Short‑Beveled 22‑Gauge Needle

Short bevel reduces risk of nerve injury

Better tactile feedback when passing through tissues

Commonly used for peripheral nerve and neuraxial techniques

Provides a safety balance between penetration and control

Ultra‑High‑Yield Exam Pearl

Short or blunt bevels = safer near nerves

Long bevels = higher nerve injury risk

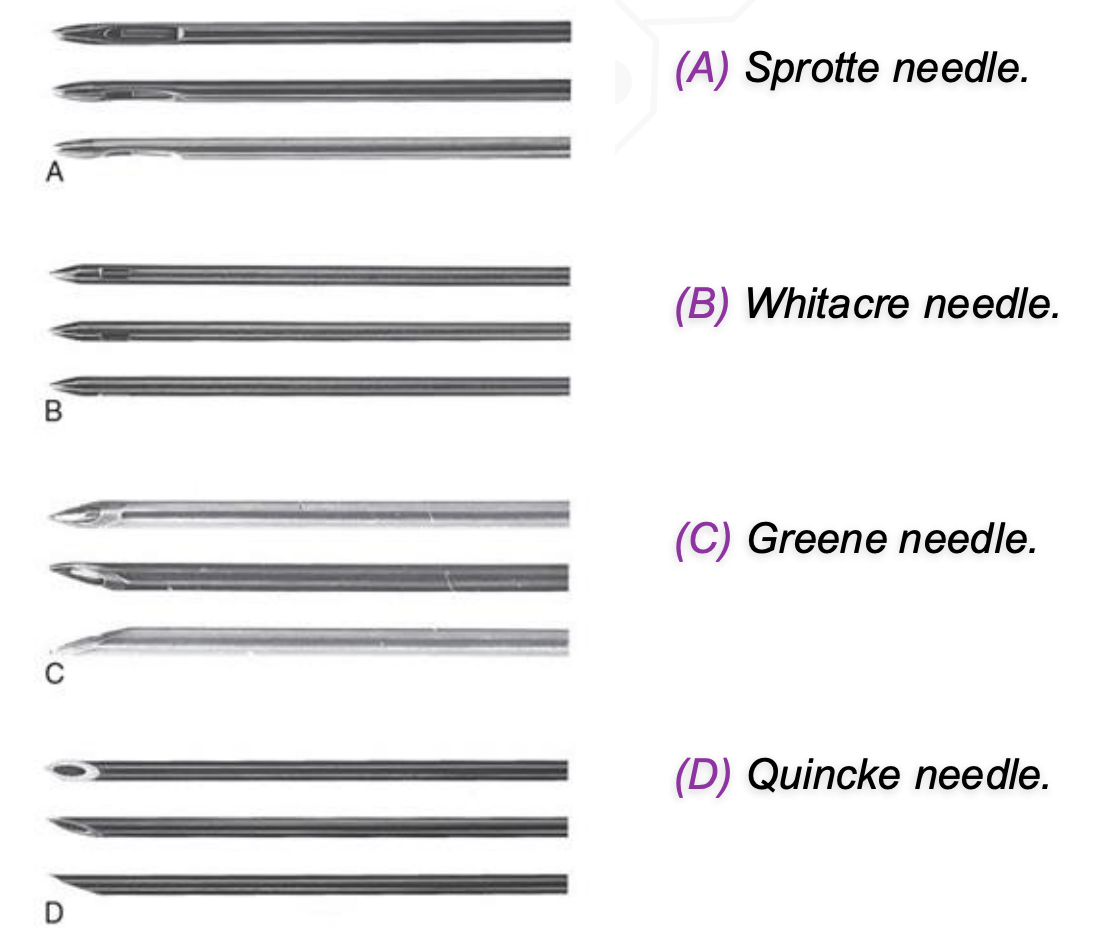

Spinal Needles

Pencil‑point (Sprotte, Whitacre) → ↓ PDPH

Cutting needles (Quincke, Greene) → ↑ PDPH

(A) Sprotte needle

(B) Whitacre needle

(C) Greene needle

(D) Quincke needle

Epidural Needles

(A) Crawford needle

(B) Tuohy needle; the inset shows a winged hub assembly common to winged needles.

(C) Hustead needle.

(D) Curved, 18-gauge epidural needle.

Tuohy = standard epidural needle

Curved tip → directs catheter

Blunt/non‑cutting bevel → ↓ dural puncture risk

Larger gauge = easier catheter passage but ↑ tissue trauma

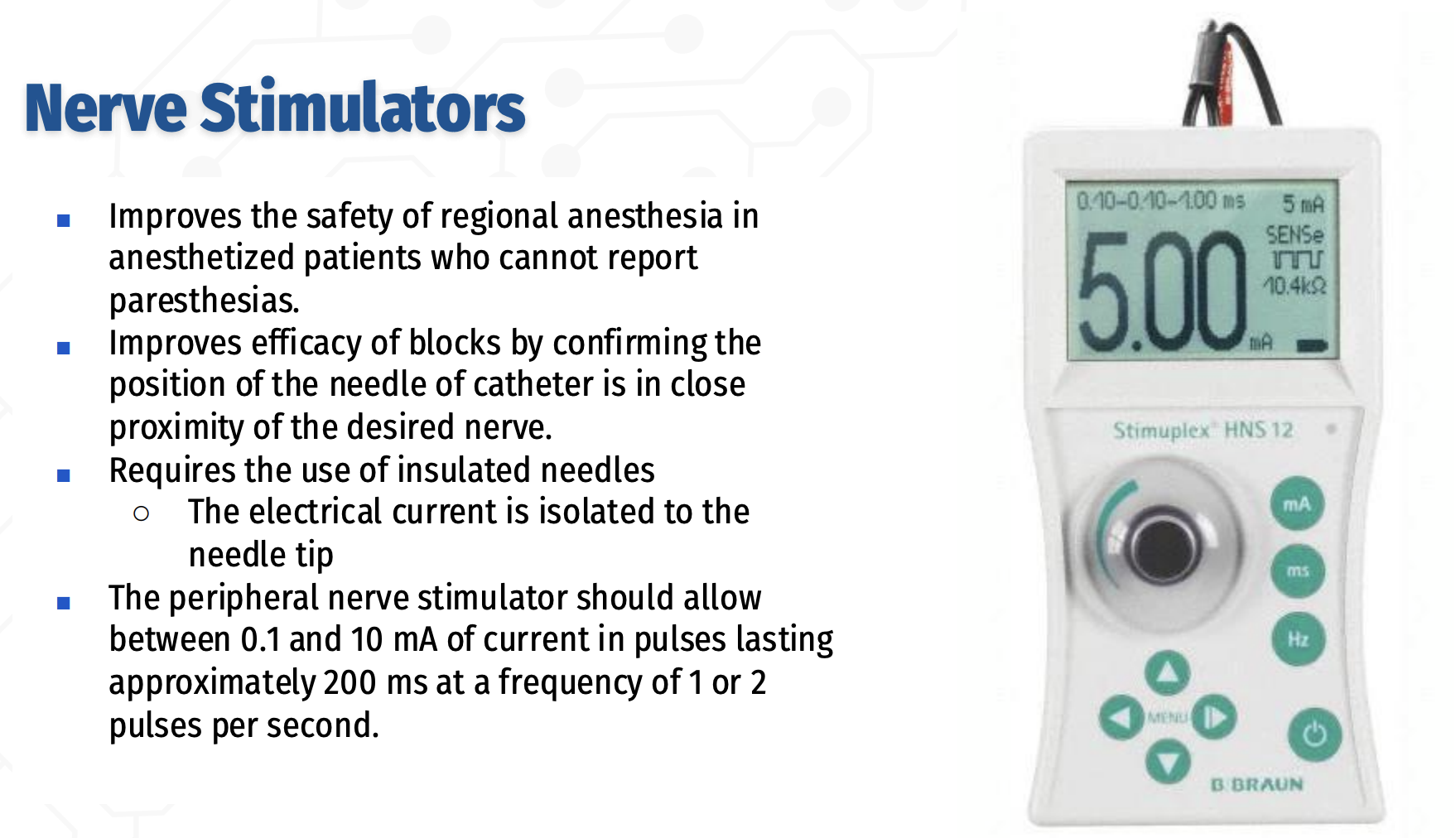

What is the role and key technical requirements of peripheral nerve stimulators in regional anesthesia?

Peripheral nerve stimulators improve the safety and efficacy of regional anesthesia, especially in anesthetized or sedated patients who cannot report paresthesias,

By confirming that the needle or catheter tip is in close proximity to the target nerve.

Their use requires insulated needles to ensure the electrical current is concentrated at the needle tip.

The stimulator should deliver 0.1–10 mA of current in pulses lasting ~200 ms at a frequency of 1–2 pulses per second.

Q: What are the key numerical settings for a peripheral nerve stimulator used in regional anesthesia?

Current range: 0.1–10 mA

Pulse duration: ~200 milliseconds

Stimulation frequency: 1–2 pulses per second

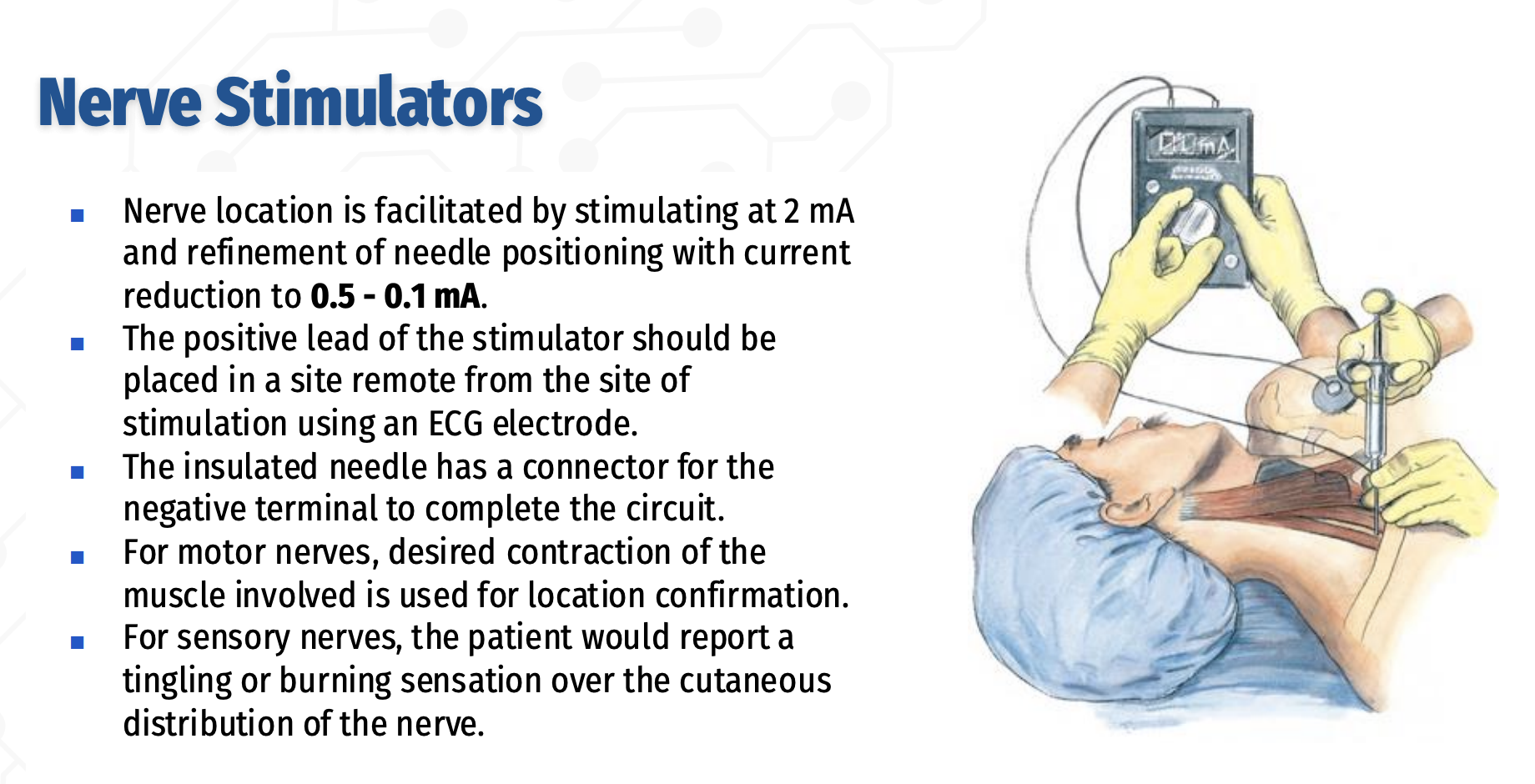

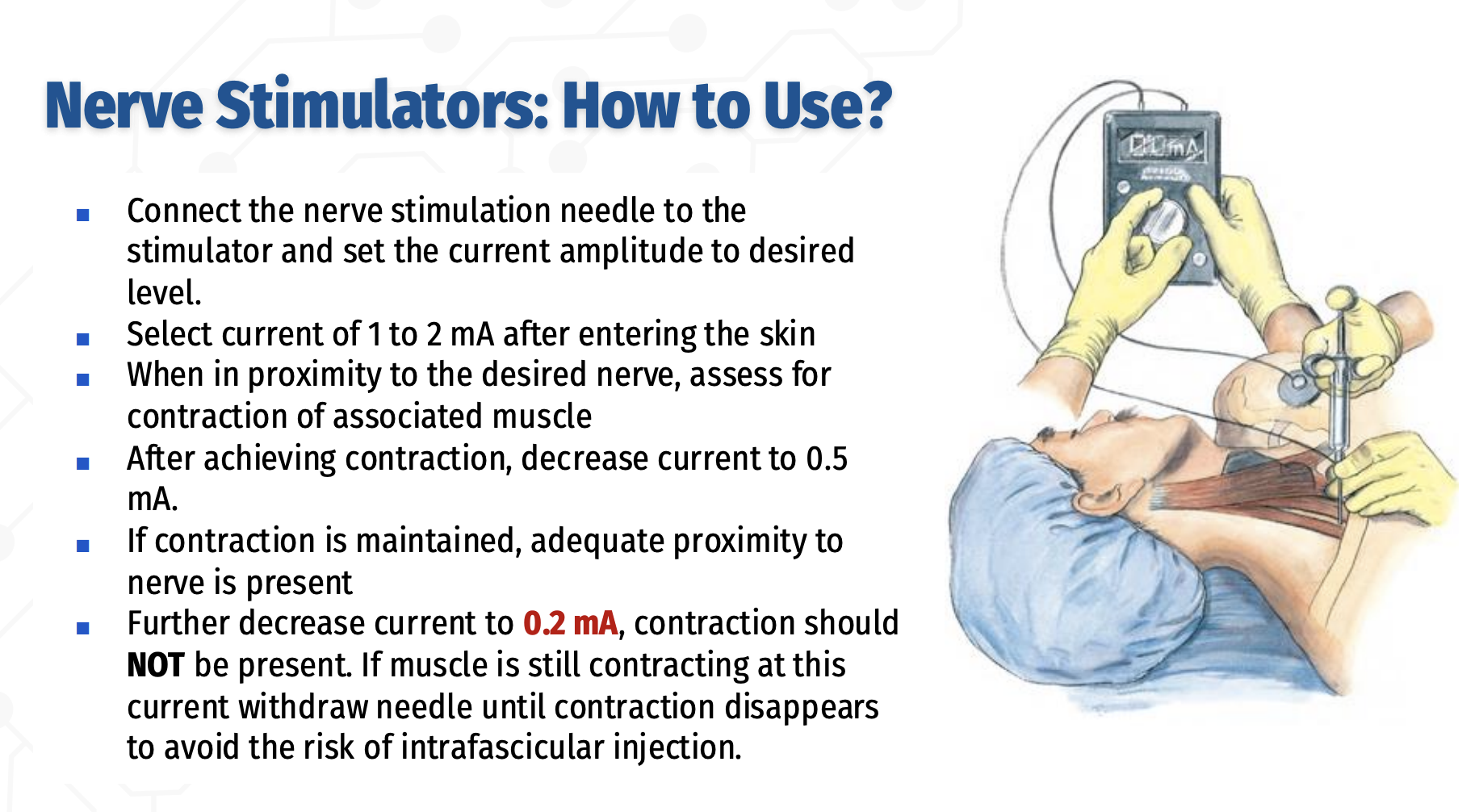

How is a peripheral nerve stimulator used to locate nerves during regional anesthesia?

Nerve location begins with stimulation at 2 mA, followed by refinement of needle position by reducing the current to 0.5–0.1 mA.

The positive electrode is placed remotely using an ECG electrode, and the negative terminal connects to an insulated needle to complete the circuit.

For motor nerves, correct placement is confirmed by the desired muscle contraction; for sensory nerves, the patient reports tingling or burning in the nerve’s cutaneous distribution.

Peripheral Nerve Stimulator – Technique & Confirmation

✅ 2 → 0.5 → 0.1 mA = find, refine, confirm

Start at 2 mA to find the nerve, reduce to 0.5 mA to refine positioning, and avoid injection if responses persist at 0.1–0.2 mA due to intraneural risk.

How is a peripheral nerve stimulator used to safely locate a nerve during regional anesthesia?

Connect the insulated nerve‑stimulating needle to the stimulator and set the desired current

After skin penetration, begin stimulation at 1–2 mA to locate the nerve

When near the target nerve, observe for contraction of the associated muscle

Once contraction is obtained, decrease the current to 0.5 mA

Sustained contraction at 0.5 mA confirms adequate needle–nerve proximity

Further reduce the current to 0.2 mA

Muscle contraction should NOT be present

If contraction persists at 0.2 mA, withdraw the needle until it disappears to avoid intrafascicular (intraneural) injection

» ✅ Inject when contraction is present at 0.5 mA

⚠ If contraction persists at ≤0.2 mA → too close → withdraw

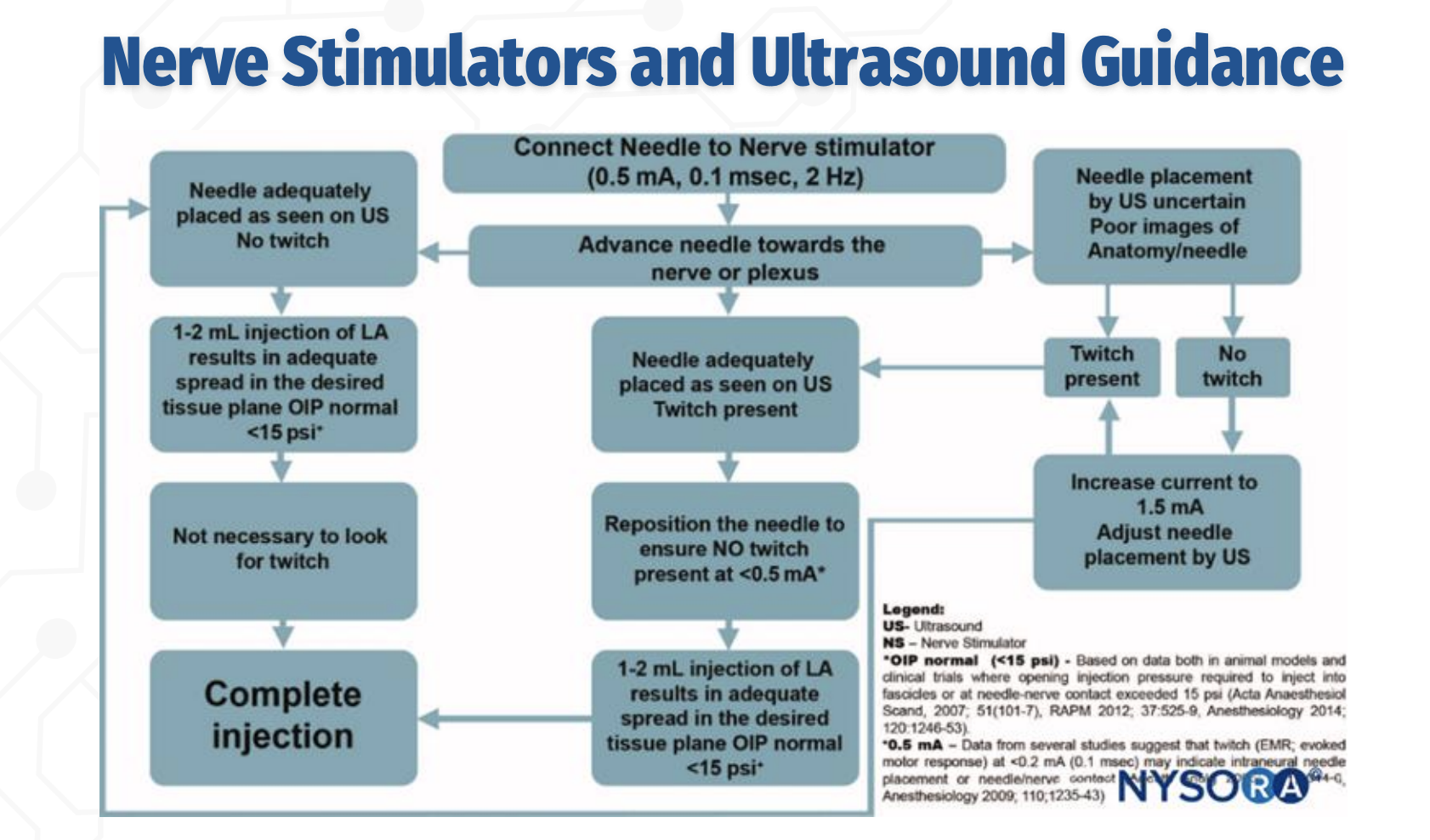

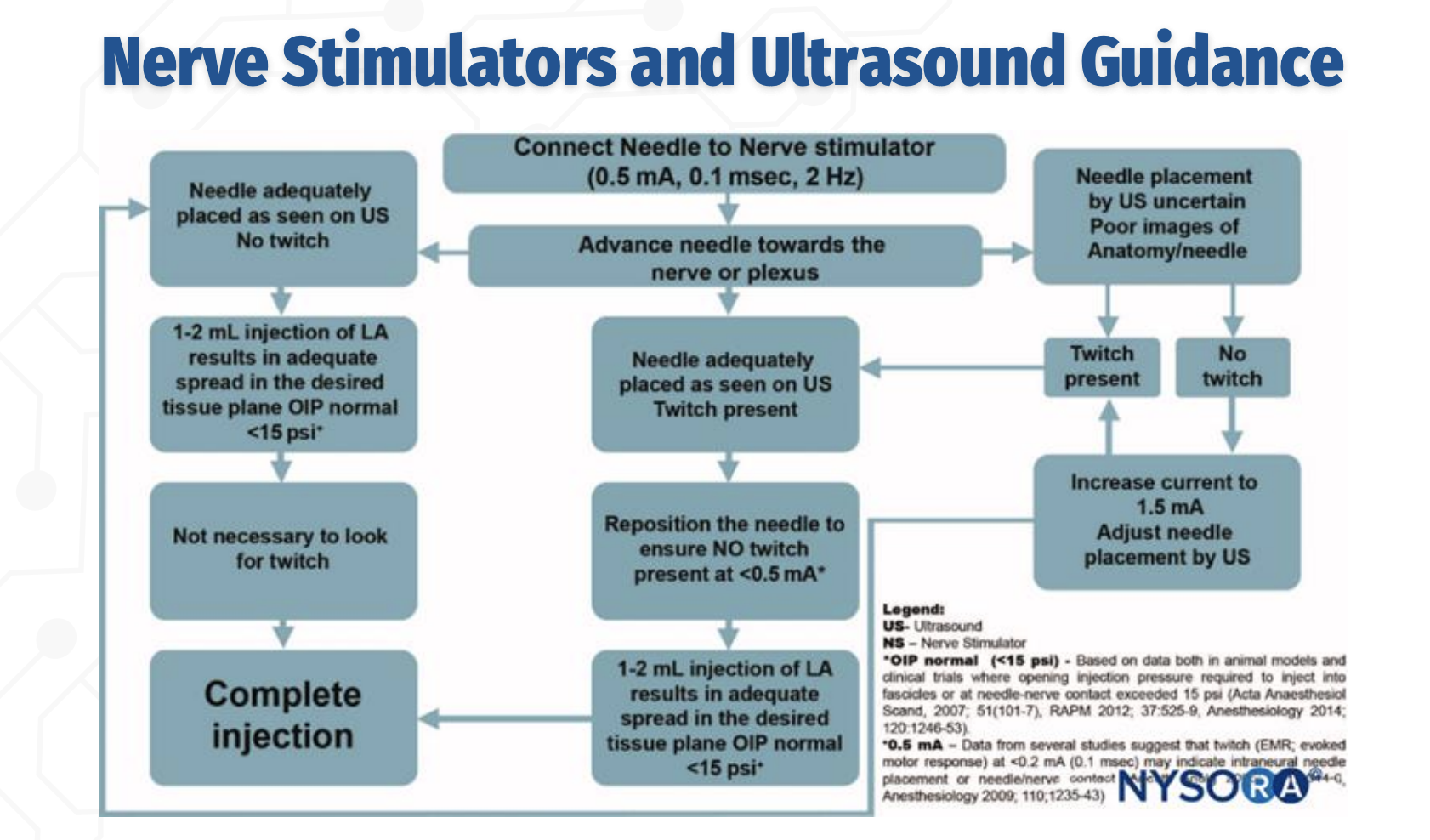

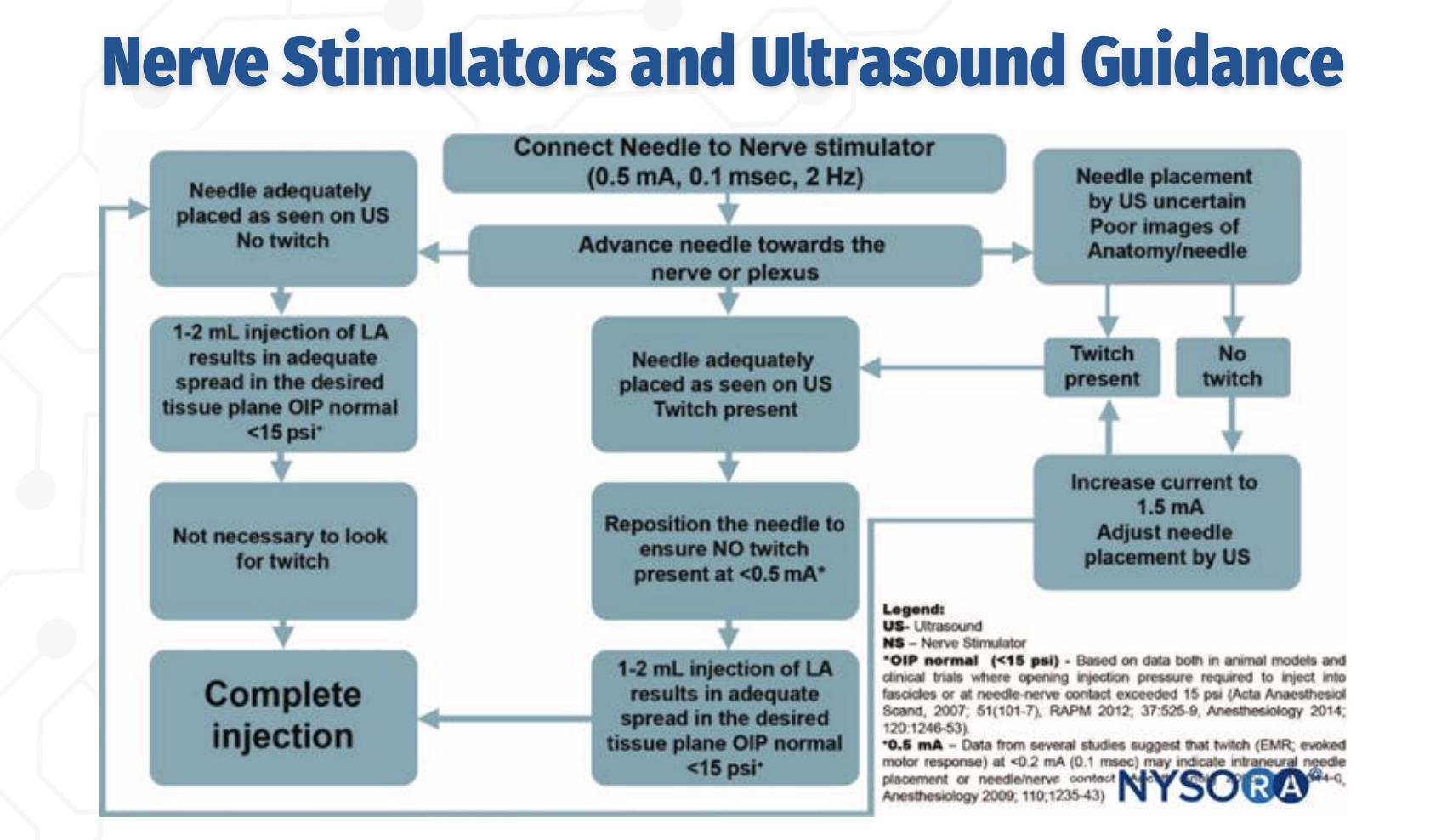

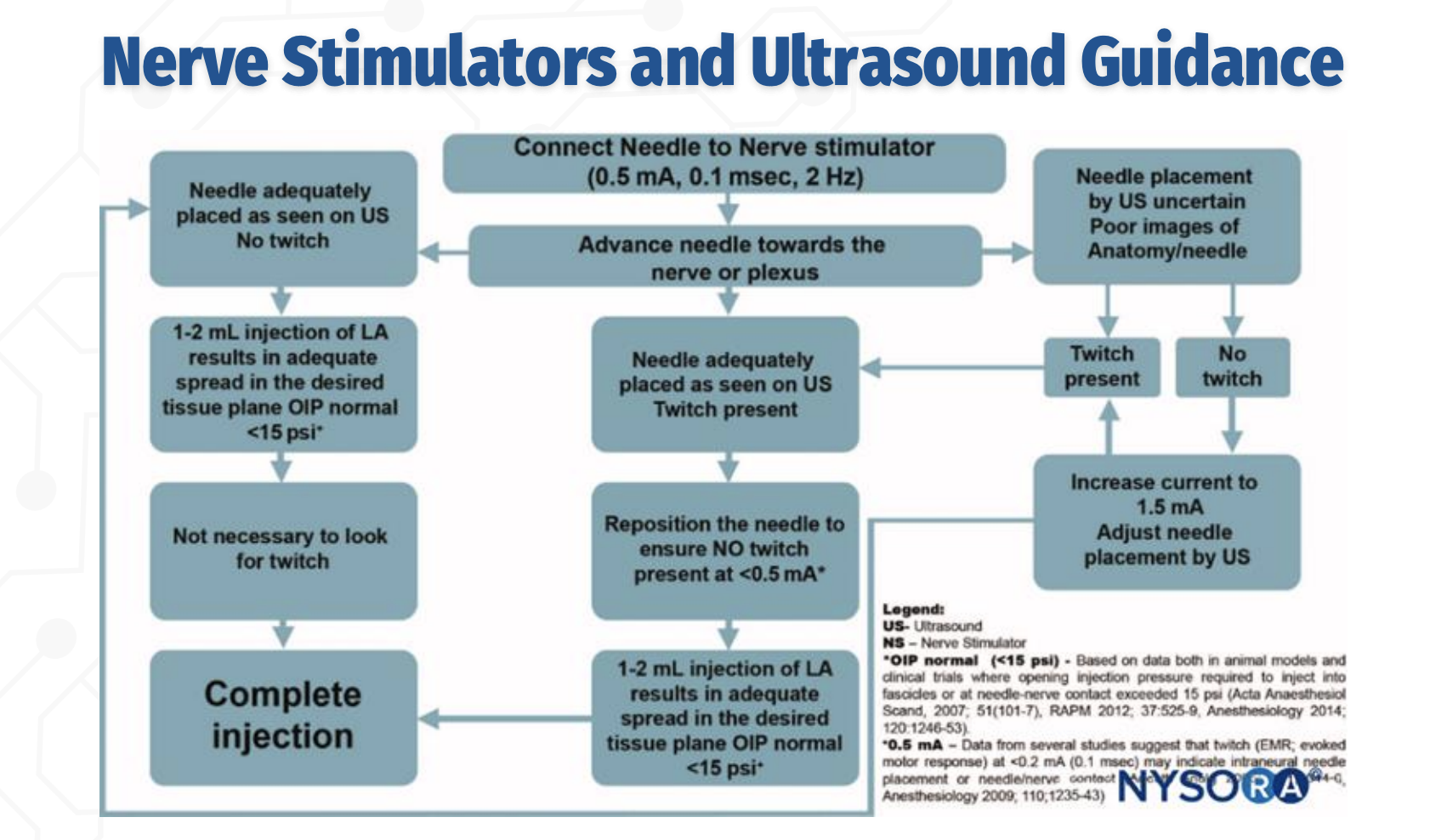

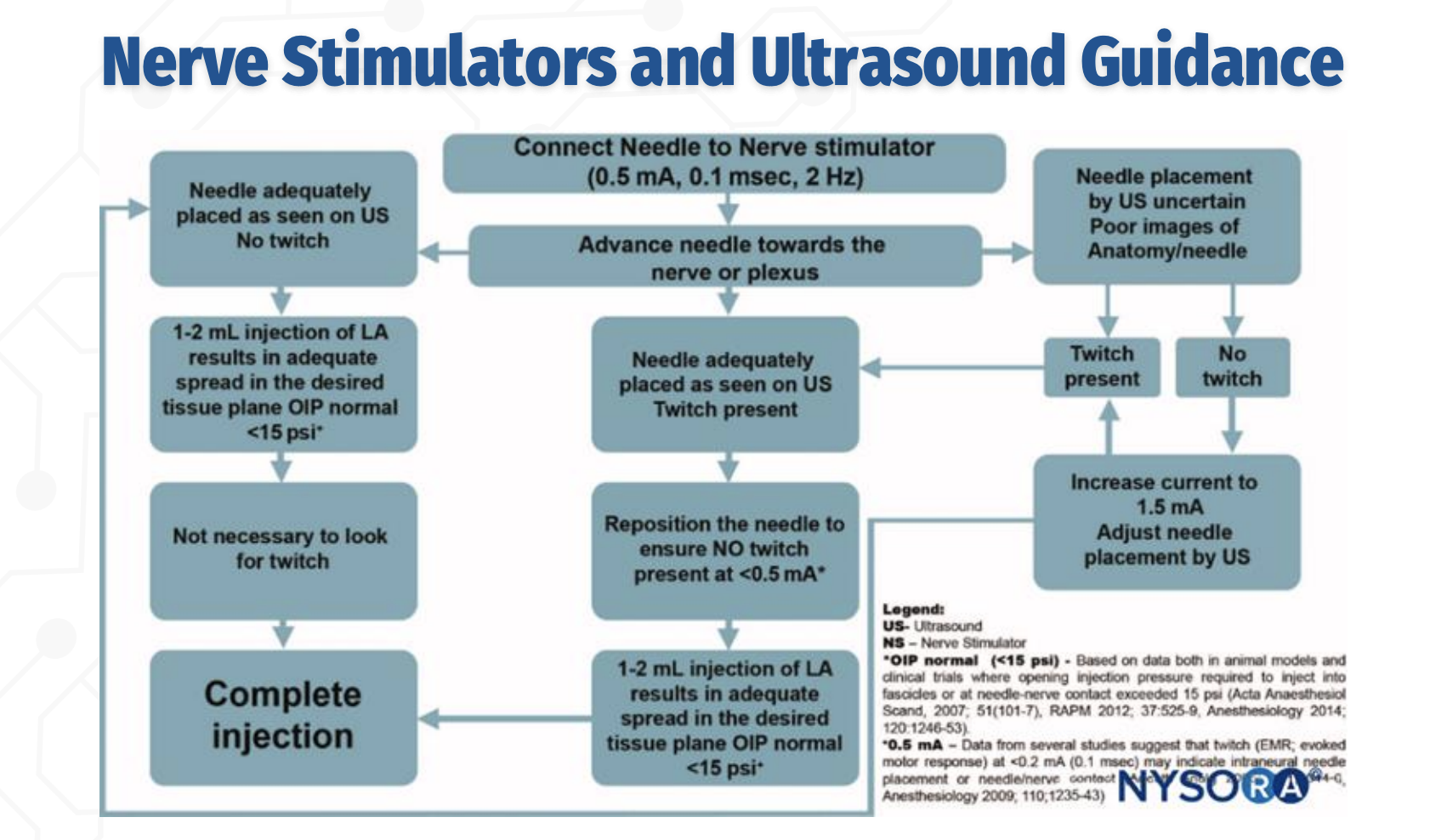

US + Nerve Stimulator: Initial Approach

The needle is advanced toward the nerve under ultrasound guidance while connected to a nerve stimulator set at 0.5 mA, 0.1 ms, 2 Hz. Ultrasound is used to visualize needle–nerve proximity, and nerve stimulation provides functional confirmation, especially when ultrasound images are poor or uncertain.

Role of Twitch With Adequate Ultrasound Imaging

Q: If the needle is clearly visualized on ultrasound, is a motor twitch required before injection?

No. If the needle tip is adequately visualized on ultrasound, and a 1–2 mL test injection produces appropriate spread in the correct tissue plane with normal opening injection pressure (<15 psi), the block may proceed without the presence of a twitch.

Interpreting Twitch Responses During Combined Guidance

Q: How should twitch responses be interpreted when combining nerve stimulation with ultrasound?

A twitch at 0.5 mA indicates close proximity to the nerve.

The needle should then be adjusted so that no twitch is present at <0.5 mA, as a persistent twitch at very low current suggests needle–nerve contact or intraneural placement, increasing the risk of nerve injury.

STOP / GO Criteria for Injection (EXAM FAVORITE)

What findings indicate it is safe to proceed with local anesthetic injection during a peripheral nerve block?

✅ Needle tip well visualized on ultrasound

✅ No motor response at ≤0.2–0.3 mA

✅ 1–2 mL test dose shows proper spread in target tissue plane

✅ Opening injection pressure <15 psi

❌ STOP if high pressure, poor spread, or twitch persists at very low current (intraneural risk)

Ultrasound confirms anatomy; nerve stimulation confirms safety — you avoid twitch at very low current, not chase it.

One‑Line Board Pearl

slide 21

Ultrasound confirms anatomy; nerve stimulation confirms safety — you avoid twitch at very low current, not chase it.

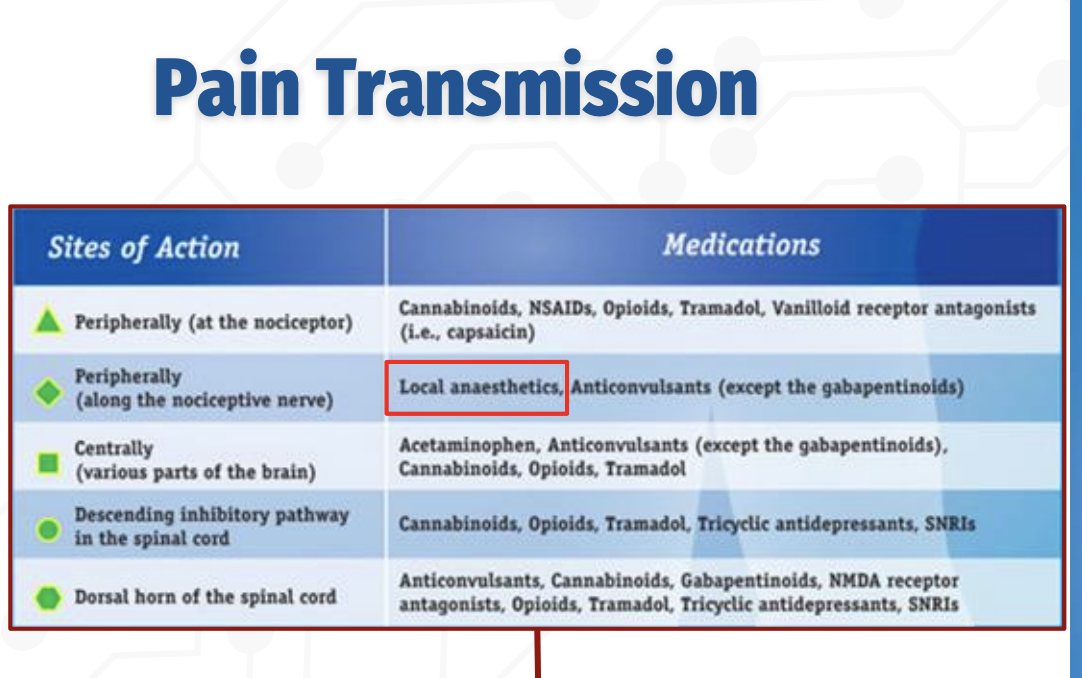

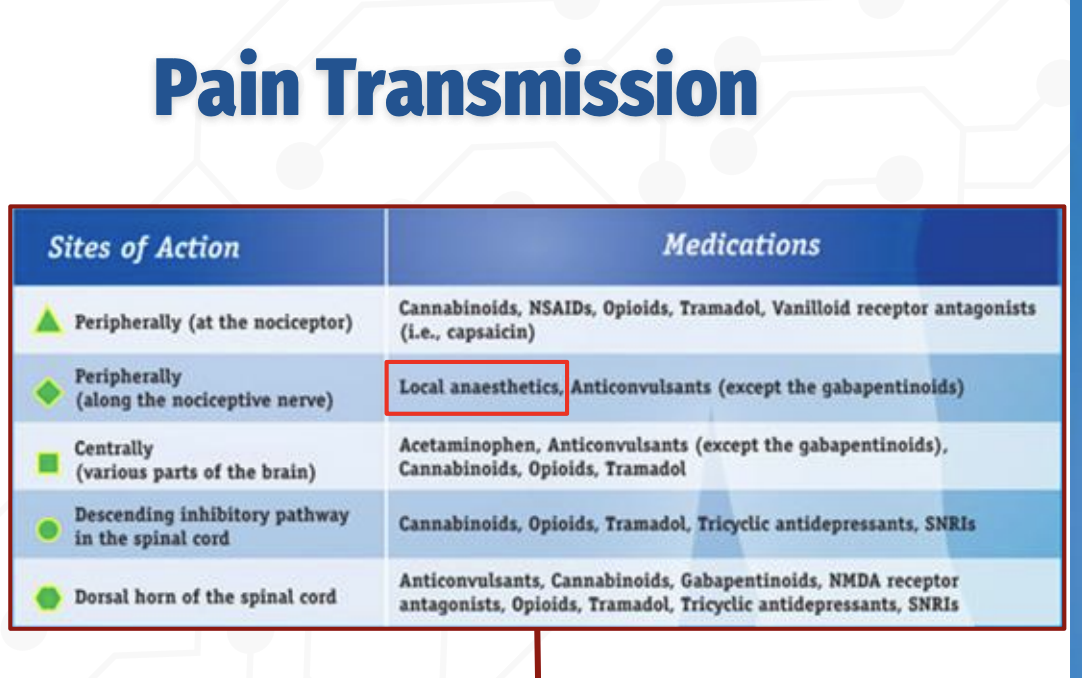

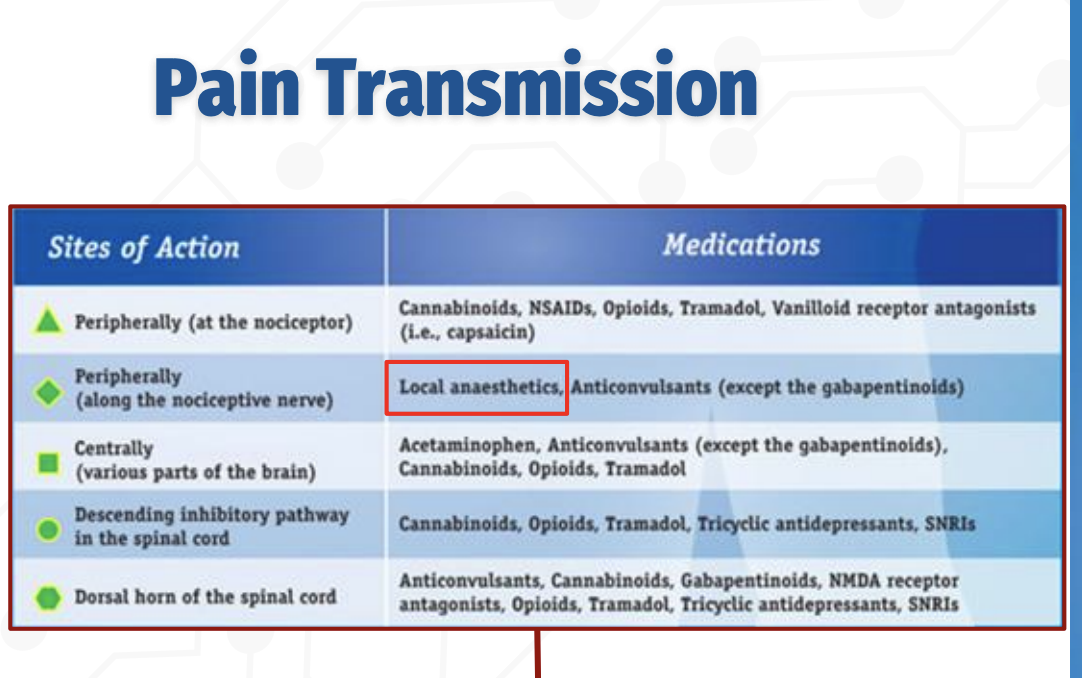

How does pain transmission occur, and where do different analgesic medications act?

Pain transmission can be modulated at multiple levels of the nervous system, and different drug classes act at specific sites:

Peripherally (at the nociceptor):

NSAIDs, opioids, tramadol, cannabinoids, and vanilloid receptor agents (e.g., capsaicin) reduce pain signaling at the site of injury.Peripherally (along the nociceptive nerve):

Local anesthetics block voltage‑gated sodium channels, preventing action potential propagation along the nerve.Centrally (brain):

Acetaminophen, opioids, tramadol, cannabinoids, and anticonvulsants alter pain perception.Descending inhibitory pathways (spinal cord):

Opioids, tramadol, cannabinoids, TCAs, and SNRIs enhance inhibitory control of pain transmission.Dorsal horn of the spinal cord:

Anticonvulsants (including gabapentinoids), NMDA antagonists, opioids, TCAs, SNRIs, and cannabinoids inhibit synaptic transmission of pain signals.

Peripheral vs Central Sites of Pain Modulation

Q: What drugs act peripherally vs centrally in the pain pathway?

Peripheral (nociceptor): NSAIDs, cannabinoids, opioids, tramadol, capsaicin

Peripheral (along nerve): Local anesthetics (block Na⁺ channels)

Central (brain): Acetaminophen, opioids, tramadol, cannabinoids, anticonvulsants

Q: What drug classes act on the spinal cord to reduce pain transmission?

Spinal Cord Modulation of Pain

Descending inhibitory pathways: Opioids, tramadol, cannabinoids, TCAs, SNRIs

Dorsal horn synapses: Anticonvulsants (gabapentinoids), NMDA antagonists, opioids, TCAs, SNRIs, cannabinoids

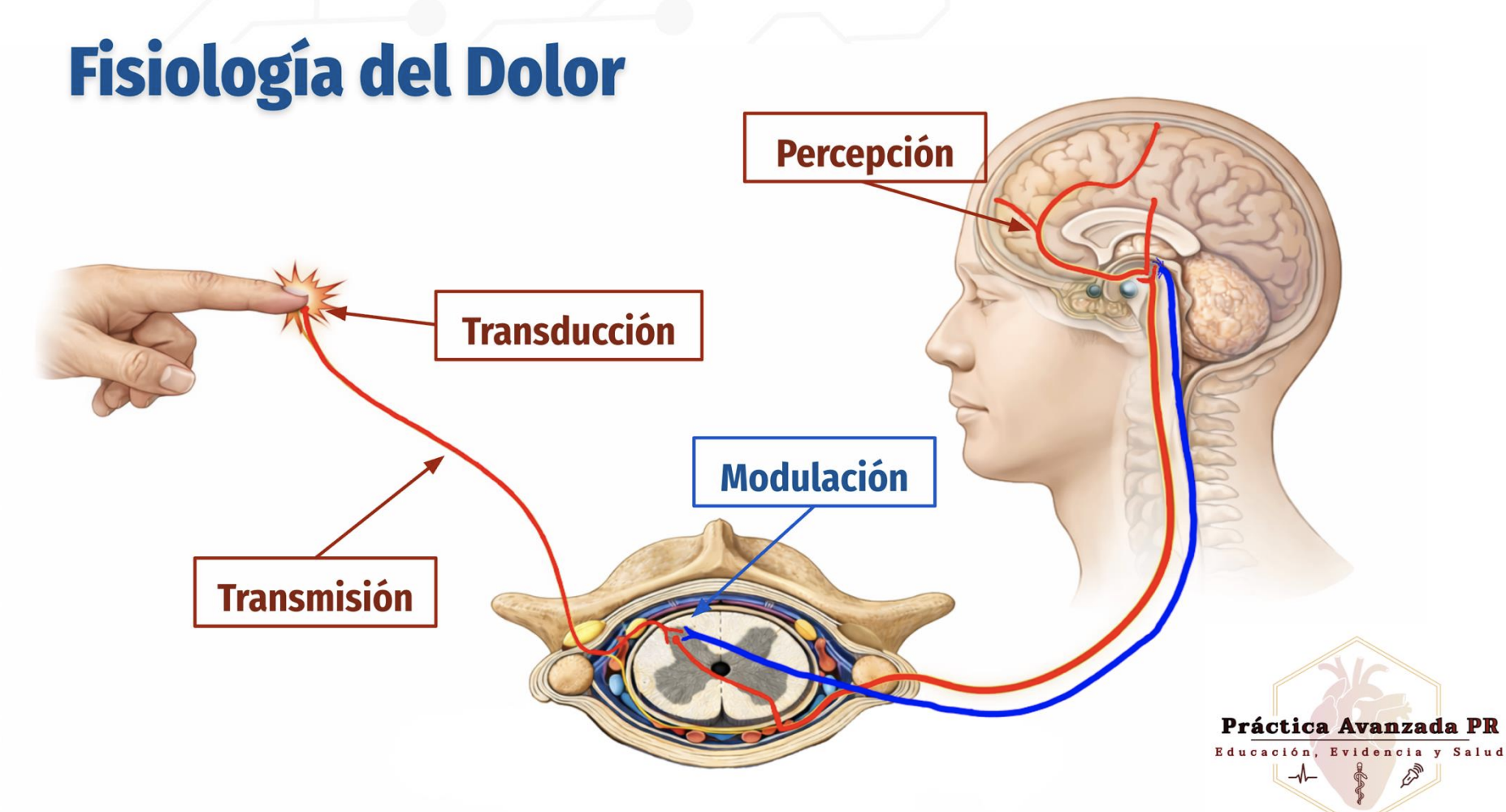

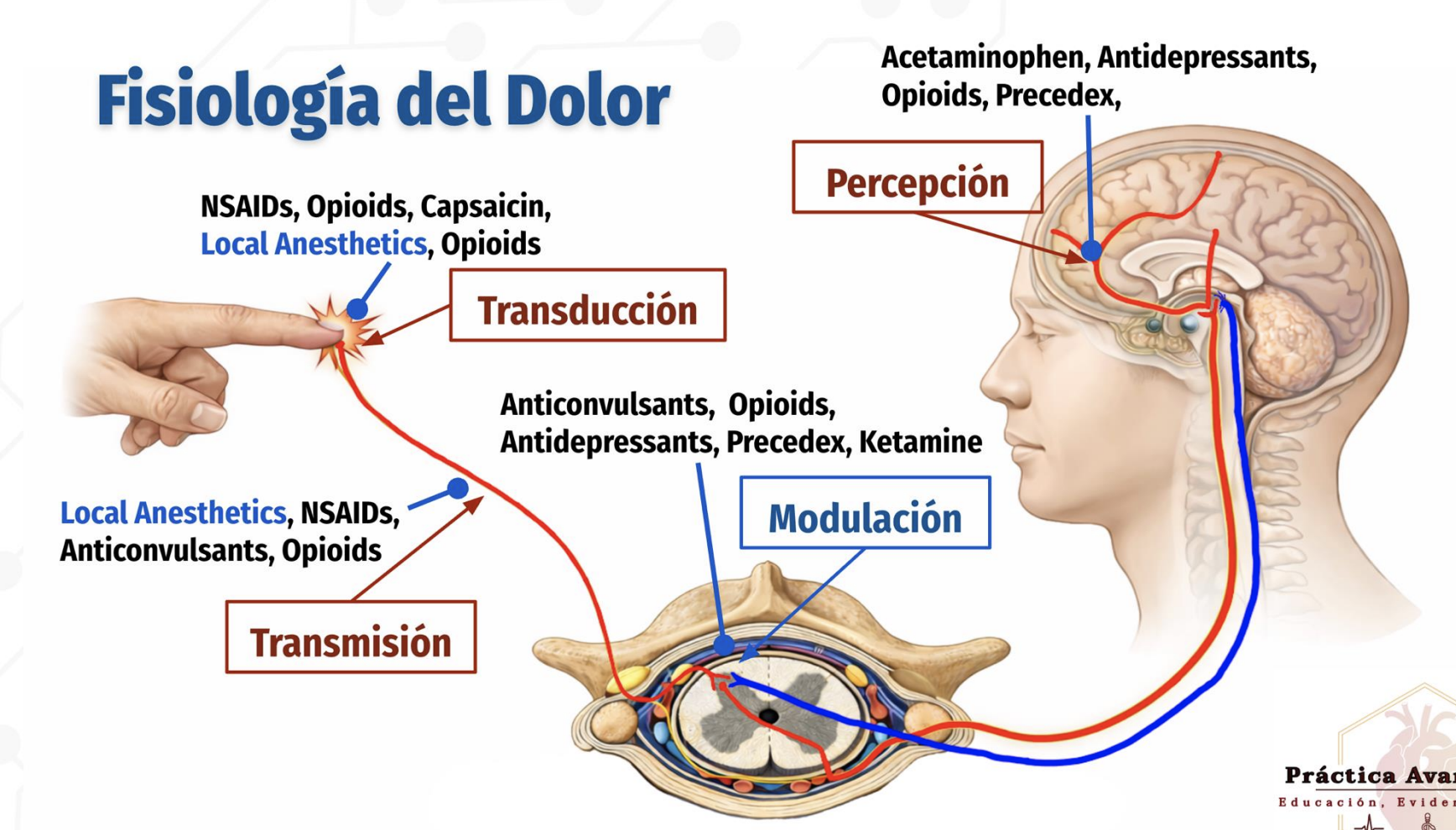

Physiology of Pain

4 stages of pain

Transduction: Conversion of noxious stimuli into nerve impulses at the site of injury

Transmission: Propagation of pain signals from peripheral nerves to the spinal cord and brain

Perception: Conscious recognition and interpretation of pain in the brain

Modulation: Alteration of pain signals via descending inhibitory pathways, primarily in the spinal cord

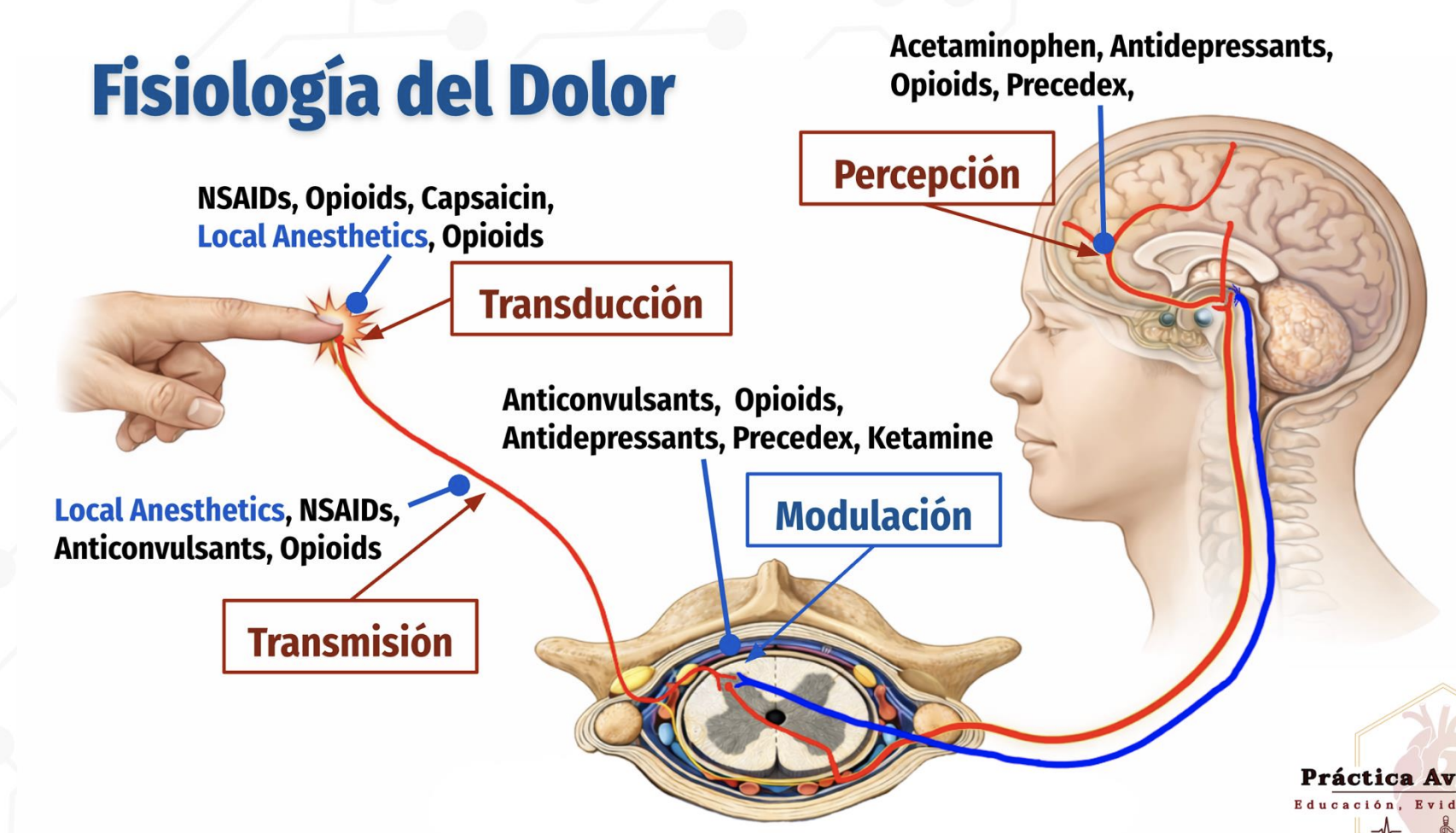

Pain physiology

four stages of pain physiology and the major drug classes acting at each stage

Transduction: Peripheral conversion of stimulus → pain signal

NSAIDs, opioids, capsaicin, local anestheticsTransmission: Pain signal travels along nerves and spinal cord

Local anesthetics, NSAIDs, opioids, anticonvulsantsPerception: Brain recognizes/experiences pain

Acetaminophen, antidepressants, opioids, PrecedexModulation: Descending inhibition of pain in spinal cord

Anticonvulsants, opioids, antidepressants, Precedex, ketamine

Where Local Anesthetics Work

Local anesthetics act at two key stages:

Transduction: Block nociceptor activation

Transmission: Block sodium channels along the peripheral nerve to stop action potential propagation

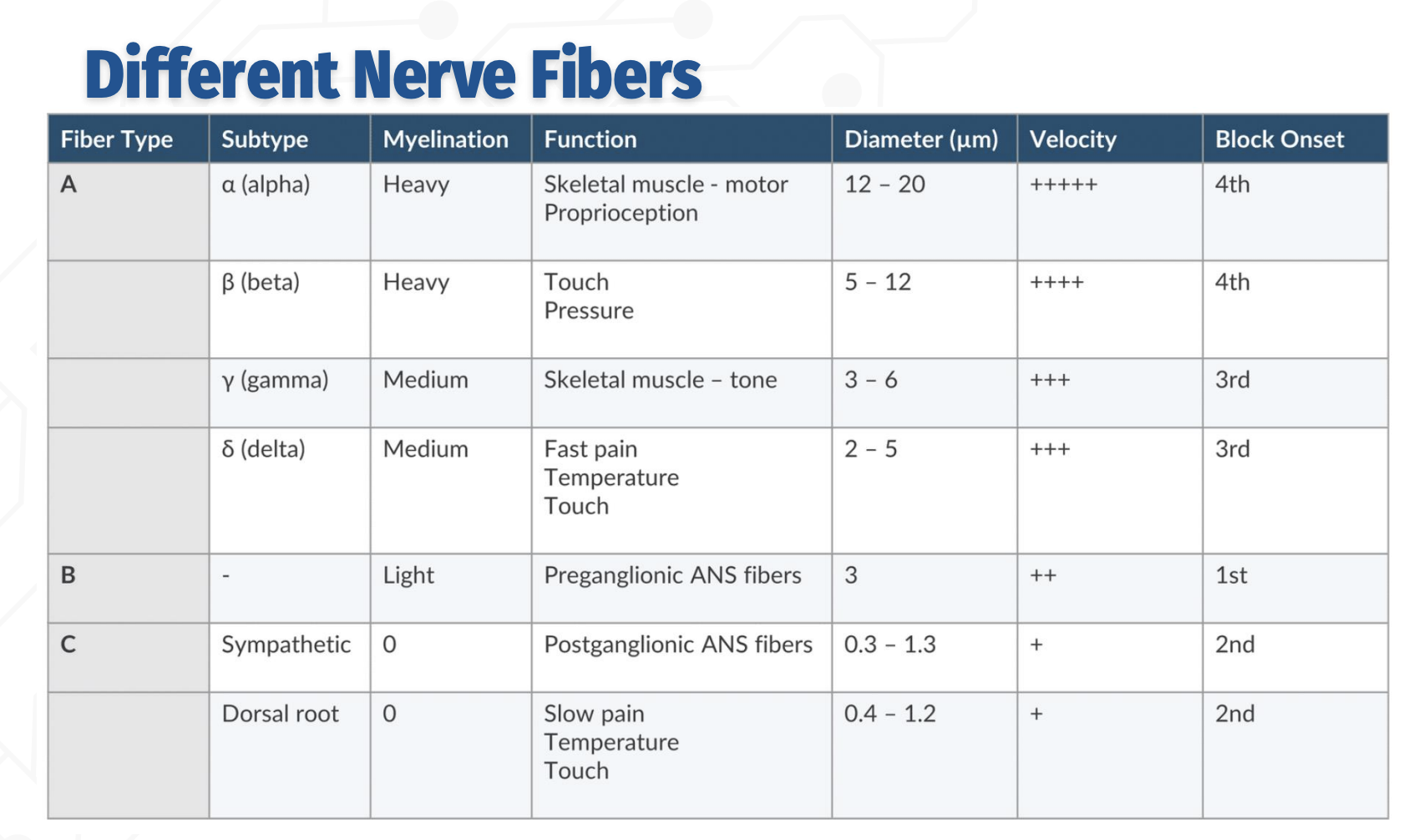

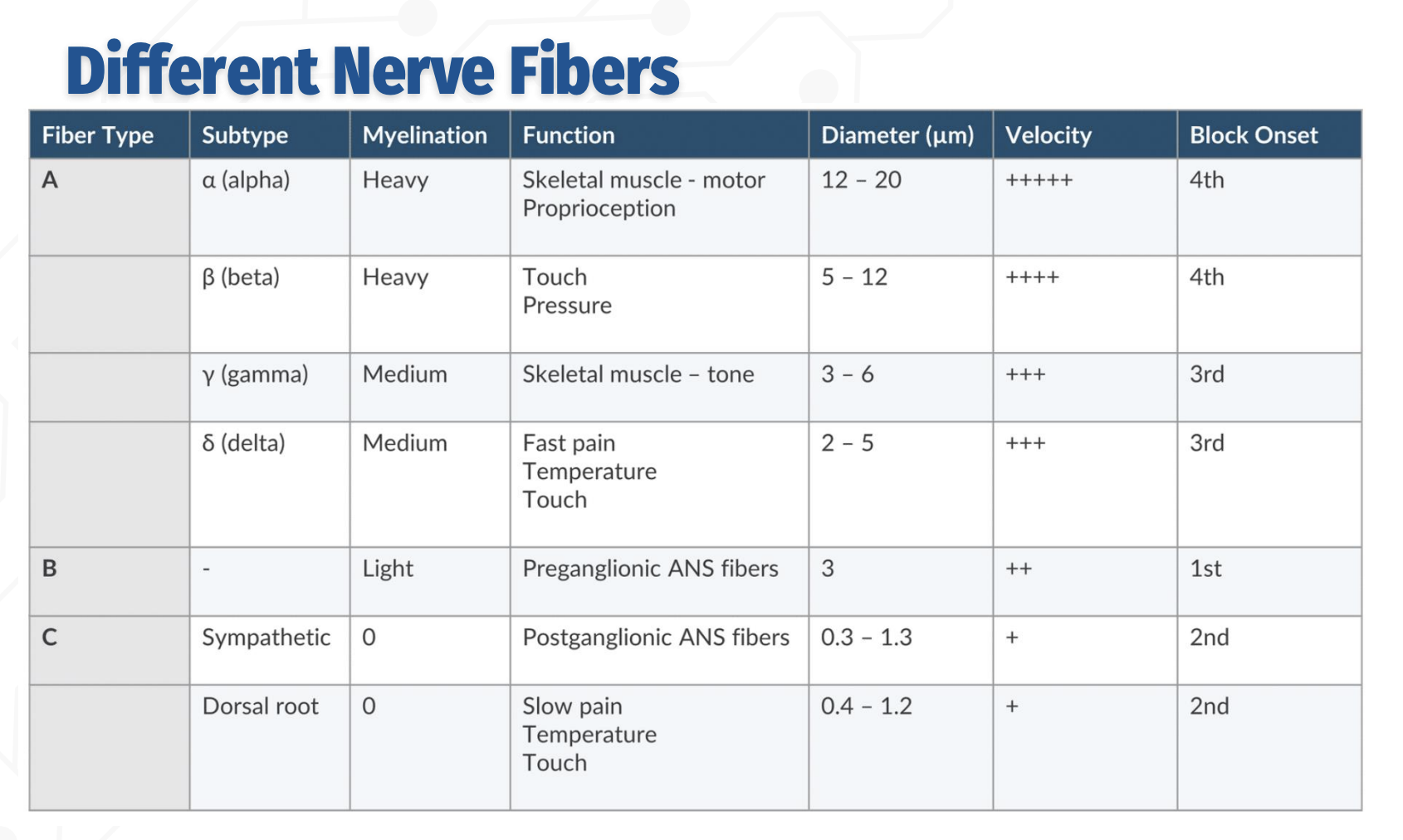

Order of block onset (from most to least sensitive):

B → C → Aδ/γ → Aβ → Aα

Order of nerve blocks - in detail

C fibers (unmyelinated):

Function: Slow pain, temperature, touch; postganglionic sympathetic fibers

Smallest diameter (0.3–1.3 µm), slowest conduction

Blocked 2nd

B fibers (lightly myelinated):

Function: Preganglionic autonomic fibers

Diameter ~3 µm, moderate conduction velocity

Blocked 1st (most sensitive)

A fibers (myelinated):

δ (delta): Fast pain, temp, touch — 2–5 µm → 3rd block onset

γ (gamma): Muscle tone — 3–6 µm → 3rd block onset

β (beta): Touch & pressure — 5–12 µm → 4th block onset

α (alpha): Motor & proprioception — 12–20 µm, fastest conduction → 4th block onset (last)

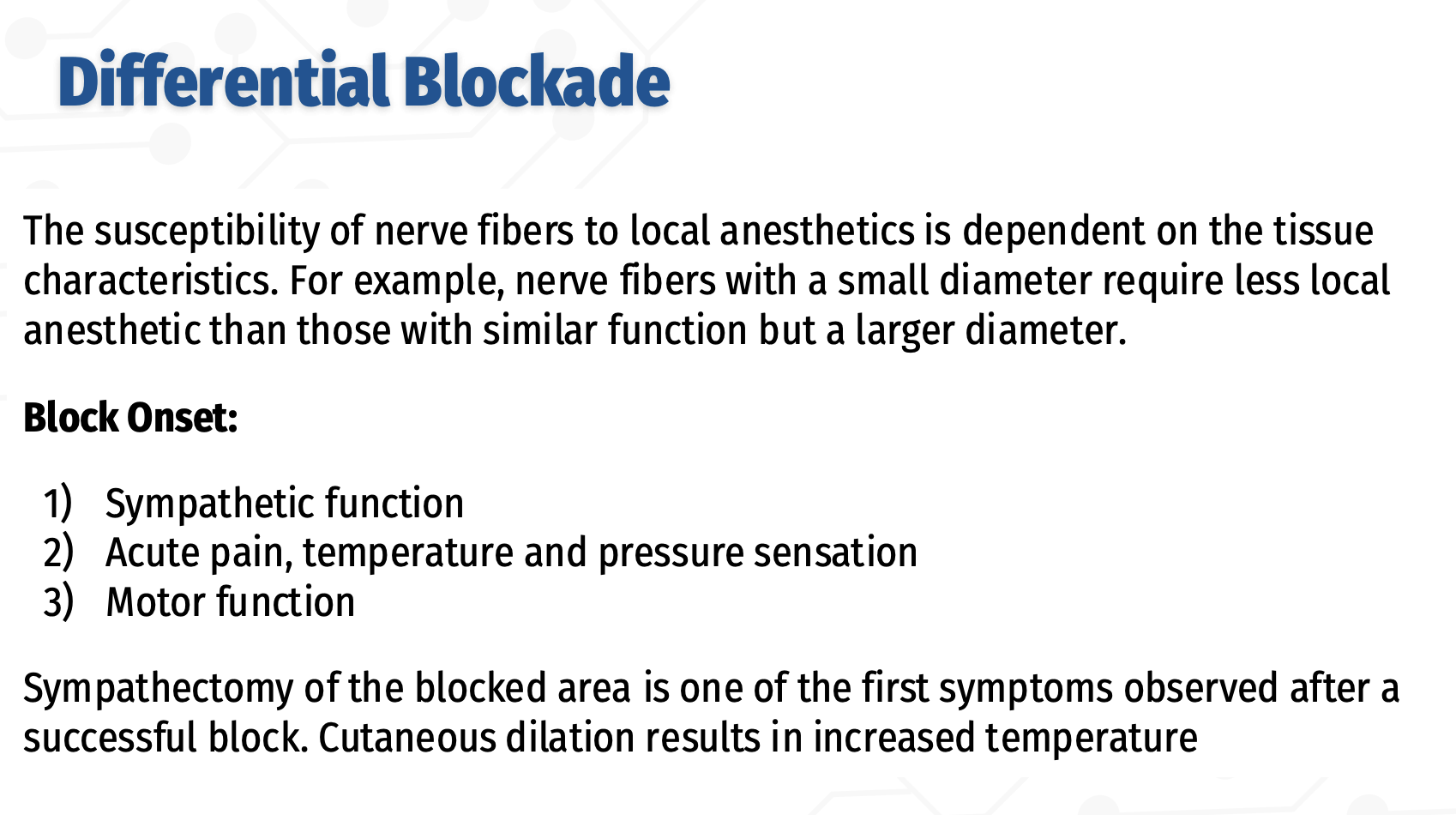

Differential Blockade

refers to the fact that different nerve fibers have different sensitivities to local anesthetics, largely based on tissue characteristics and fiber diameter. Smaller fibers require less local anesthetic to be blocked than larger fibers, even if their functions are similar.

Differential Blockade

Order of Block Onset:

Sympathetic fibers → first to be blocked

Acute pain, temperature, and pressure sensation → second

Motor function → last

» A hallmark of early blockade is sympathectomy, which causes cutaneous vasodilation and increased skin temperature in the blocked region