Explaining all theories concerning aggregate demand, aggregate supply, and the Phillips curve

1/34

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

35 Terms

Aggregate Demand (AD) definition

is the total demand for goods and services within an economy at a given overall price level and in a given time period. It is expressed as the total amount of money exchanged for those goods and services.

AD slopes downward due to

Real wealth effect

Interest rate effect

Net export effect

Real Wealth Effect

refers to the phenomenon where an increase in the overall price level reduces the purchasing power of wealth, leading to lower consumer spending and thus lower aggregate demand.

Interest Rate Effect

is the impact that changes in interest rates have on consumer spending and investment. When interest rates rise, borrowing costs increase, leading to decreased spending and lower aggregate demand.

Net Export Effect

is the change in a country's net exports due to shifts in the exchange rate caused by changes in the domestic price level. When domestic prices rise, exports become relatively more expensive for foreign buyers, reducing demand for exports and increasing demand for imports, thereby decreasing aggregate demand.

Components of AD

include consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports. These components collectively determine the total demand for goods and services in an economy at a given price level.

Why the AD might shift?

Possible reasons for shifts in aggregate demand include changes in consumer confidence, fiscal policy adjustments, variations in interest rates, and external economic conditions.

An increase in AD would be a shift to the right. A decrease in AD would be a shift to the left

Spending multiplier

In Keynesian economics, Aggregate Demand does not change only by the orginal amount of spending

When the government increases spending, AD increases by more than that amount because of the spending multiplier

Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC)

The proportion of an additional income that is spent (consumed); for example, if your MPC is 0.15 that means for every $1 more income you get, you will save 25 cents and spend 75 cents

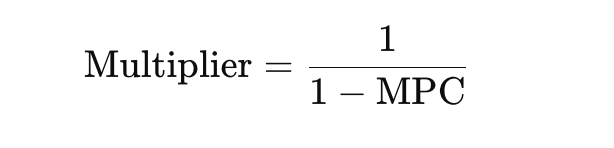

Multiplier formula

If MPC is large → People spend more → Multiplier is large → AD increases strongly

Fiscal Policy

The use of taxes, government spending, and government transfers to stabilize an economy; the word “fiscal’ refers to tax revenue and government spending

Expansionary Fiscal Policy

To expand the economy by increasing aggregate demand, which leads to increased output, decreased unemployment and higher price level

→ Fix recessions

Contractionary Fiscal Policy

The use of fiscal policy to contract by decreasing aggregate demand, which will lead to lower output, higher unemployment, and a lower price level

→ Fix booms

Tax level of fiscal policy

The government has two main fiscal policy tools for increasing GDP

Keep taxes the same → increase government spending (G rises)

If taxes stay the same, the government is not collecting extra money

So to spend, the government must borrow money (take on more debt)

With higher government spending, while consumption (C), investment (I), and net export (NX) stay roughly the same, GDP increases

Keep the government spending the same → lower taxes (taxes fall)

If taxes decrease, households and firms have more money available

They will spend more → C falls, and I may increase

Since G stays constant but C and I rise, GDP increases

But because the government is collecting less tax revenue while spening the same, it again has to borrow more

→ Both fiscal tools involve higher government debt if spending doesn’t decrease. But in both cases, GDP rises

Active Fiscal Policy

During recessions, consumers become pessimistic and reduce their consumption. This reduction causes aggregate demand (AD) to fall, pushing real GDP down

The government can counter this by increasing its spending (G↑). Due to the multiplier effect, the total increase in AD is larger than the initial rise in government spending. Therefore, government intervention can stimulate output more quickly and strongly than waiting for markets to self-correct

When the government increases spending (G↑), the AD curve shifts to the right

Because of the multiplier effect, the shift is larger than the initial fiscal change (AD₁ → AD₂ with a noticeable gap)

Because an increase in government spending creates a multiplied increase in AD, active fiscal policy stabilizes the economy during recessions

Short-run Aggregate Supply (SRAS)

The positive relationship between the aggregate price level and amount of aggregate output supplied in an economy

Upward sloping in the short run

Why “upward sloping in the short run”? (Keynesian economics)

It slopes upward because some prices rise faster than others, which creates a temporary boost that encourages firms to increase output in the short run

Keynesian economics

Aggregate demand is more likely than aggregate supply to be the primary cause of a short-run economic event like a recession

Wages and prices can be sticky, and so, in an economic downturn, unemployment can result

Sticky wages

When the overall price level (inflation) increases,

Wages and many input costs don’t actually adjust immediately

Especially because wages are usually set by contracts

→ Output prices rise quickly + input costs rise slowly (Thực ra cái này có thể hiểu là Revenue tăng (doanh thu tăng) - Doanh nghiệp bán hàng ở mức giá can hơn dự tính → tiền thu về nhiều hơn labor costs (tiền lương) không tăng ngay → vì tiền lương ký theo hợp đồng dài hạn → bị sticky → không đổi ngay được => Giá bán tăng mà chi phí chưa tăng → lợi nhuận tăng → doanh nghiệp sản xuất nhiều hơn)

Sticky prices

The hassle and cost of changing prices (printing menus, updating systems, negotiating contracts = menu costs)

So when:

Demand decreases, or

The overall price level rises

Some firms don’t change their prices immediately

Instead, they adjust by increasing output first, and only update their prices later

SRAS shifts

Anything that will shift the SRAS curve, also called an aggregate supply shock; if the prices of any of the factors of production change, or firms expect those to change, SRAS will shift

Subsides for business

Productivity

Input prices

Taxes on business

Expectations about inflation

Anything that makes production more expensive or more difficult, or any belief by firms that this will happen, will cause the SRAS to shift to the left.

Long-run Aggregate Supply (LRAS)

A curve that shows the relationship between price level and real GDP that would be supplied if all prices, including nominal wages, were fully flexible; price can change along the LRAS, but output cannot because that output reflects the full employment

Full employment (potential output)

The amount of real GDP that an economy would produce if it is using all of its factors of production efficiently

Why LRAS is vertical?

The LRAS represents a pint on a country’s PPC, translated into the AD-AS model. Every point on the PPC represents the maximum sustainable capacity for production in an economy. This value of real GDP represents the economy’s maximum sustainable capacity given its current stock of resources

LRAS is determined by

Labor

Capital

Natural resources

Technology

The short-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment

The SRAS curve tells us that firms will respond to inflation by producing more

If you want to produce more, you will need to hire more workers, so the unemployment rate decreases → SRAS captures the tradeoff between inflation and unemployment

When the price level increases, producers are willing to make more and hire more workers because sticky wages make them a better bargain

When the price level decreases, producers are willing to make less because wages make workers not as good of a deal and producers sell less

Short-run disequilibrium

In the short-run, prices and wages are sticky. So if AD changes unexpectedly, the economy will NOT immediately return to full employment (Yₚ)

When AD decreases - recession (negative output) → AD shifts left

→ What governments usually do (policy): Expansionary (stimulus) fiscal or monetary policy

AD increases - inflation/boom (positive output) → AD shifts right

→ Contractionary policy to reduce inflation

Why recession when AD falls? Because sticky wages prevent immediate recovery. Firms cannot cut wage costs, so they cut output → unemployment rise. Keynesians argue government intervention stops deep recessions

Why contraction when AD rises? If the economy overheats, spending is too high, causing inflation. Government can slow demand (higher taxes, lower spending, raising interest rates)

Long-run Self-Adjustment

In the long run, wages are no longer sticky. They adjust fully

When wages adjust, SRAS shifts and the economy returns to potential output without government action

If the economy is in recession (AD falls), wages eventually fall, reducing production costs → SRAS shifts right, output returns to Yf

If inflation/boom (AD rises), wages eventually rise, costs increase → SRAS shifts left, output returns to Yf

→ In the long run, the economy goes back to full employment by itself

Classical economists believe the government should not intervene because the economy will fix itself when wages fully adjust → Government unnecessary in the long run (Classical)

Keynesian economics: The government should intervene because of sticky prices and wages

Fiscal Policy (Keynes vs Critics)

Keynesian View: Keynesians argue that fiscal policy (government spending and taxation) plays a crucial role in stabilizing the economy, especially during recessions

The government must act when the private sector cannot generate enough spending

Multiplier effect is important: More spending → more income → more spending → larger impact

Most useful in recessions (During recessions, private sector spending is low. Government spending fills the gap, lifting the economy back toward full employment)

Classical View: Critics believe fiscal policy is less effective, or even harmful

Economy self-corrects, policy lags

Crowding out reduces impact (Government spending may lead to higher interest rates → Higher interest rates reduce private investment spending → Partially or fully cancels out the impact of fiscal stimulus

Debt risks (Continuous government spending increases public debt) → Debt may harm long-run growth)

The Phillips curve

A graphical model showing the relationship between unemployment and inflation using the short-run Phillips curve (SRPC) and the long-run Phillips curve (LRPC)

Short-run Phillips curve (SRPC): a curve inverse short-run relationship between the unemployment and the inflation rate

Long-run Phillips curve (LRPC): A curve illustrating that there is no relationship between the unemployment rate and inflation in the long run, the LRPC is vertical at the natural rate of unemployment

SRPC (Short-run Phillips Curve)

Each point on the Short-Run Phillips Curve (SRPC) represents a combination of inflation and unemployment given that current inflation expectations remain unchanged.

When we move along the SRPC (for example, from point 1 to point 2), this implies a change in aggregate demand (AD) in the AD–AS model. A decrease in unemployment is associated with higher inflation in the short run, assuming expectations remain constant.

If the SRPC shifts left or right, this is caused by changes in short-run aggregate supply (SRAS).

A decrease in SRAS (a leftward shift) leads to a rise in inflation at every level of unemployment (a higher price level), causing the SRPC to shift rightward.

An increase in SRAS (a rightward shift) lowers inflation, causing the SRPC to shift leftward.

LRPC (Long-run Phillips Curve)

The Long-Run Phillips Curve (LRPC) is vertical at the natural rate of unemployment.

In the long run, there is no trade-off between inflation and unemployment. The government cannot continuously reduce unemployment by increasing inflation.

Expectations in the Phillips Curve

The Phillips curve shows a short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment. But this trade-off does not last forever because people adjust their expectations

If workers and firms expect higher inflation, they demand higher wages

Higher wages increases firms’ costs → SRAS shifts left (upwards)

This results in higher inflation at every unemployment level

→ The short-run Phillips curve (SRPC) shifts upward (to the right)

There is now no improvement in unemployment, only higher inflation → the tradeoff worsens

Supply Shocks (oil crisis)

A negative supply shock (such as rising oil prices, war, natural disaster) increases production costs

SRAS shifts left (prices ↑, output ↓)

Inflation rises while unemployment rises → known as stagflation

→ The SRPC shifts to the right

Positive supply shock

Suppose a country suddenly discovers a huge new supply of natural gas. This makes energy much cheaper for firms. As a result, production costs fall for many industries (transportation, manufacturing, power generation, farming, etc.)

→ Because when the economy experiences a positive supply shock that reduces expected inflation, the long-term trade-off between inflation and unemployment improves. The whole Phillips Curve moves to a new position with less inflation at every unemployment rate

→ Positive supply shock → SRPC shifts left (cost falls → inflation falls → unemployment falls)