BME 452 Exam 2

1/38

There's no tags or description

Looks like no tags are added yet.

Name | Mastery | Learn | Test | Matching | Spaced | Call with Kai |

|---|

No analytics yet

Send a link to your students to track their progress

39 Terms

Deformation

change in shape sufficient to cause loss of function

Types of Deformation

Time Independent

elastic

plastic

buckling

Time Dependent

creep

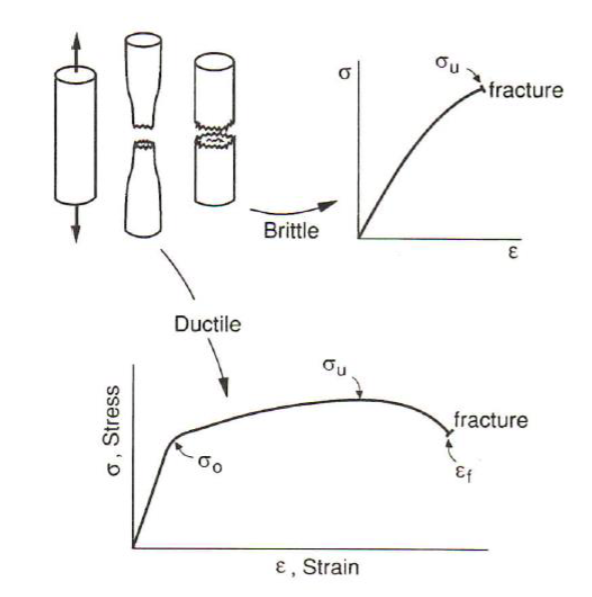

Fracture

cracking into two or more pieces

Types of Fracture

Static Loading

brittle

ductile

rupture

Dynamic Loading

fatigue

crack growth

Most Common Biomaterial Failure Modes

mechanical failure (fracture, fatigue, wear)

corrosion and chemical degradation

biological reaction

design and manufacturing choices

poor biocompatibility/immune response

infection related failure (biofilm)

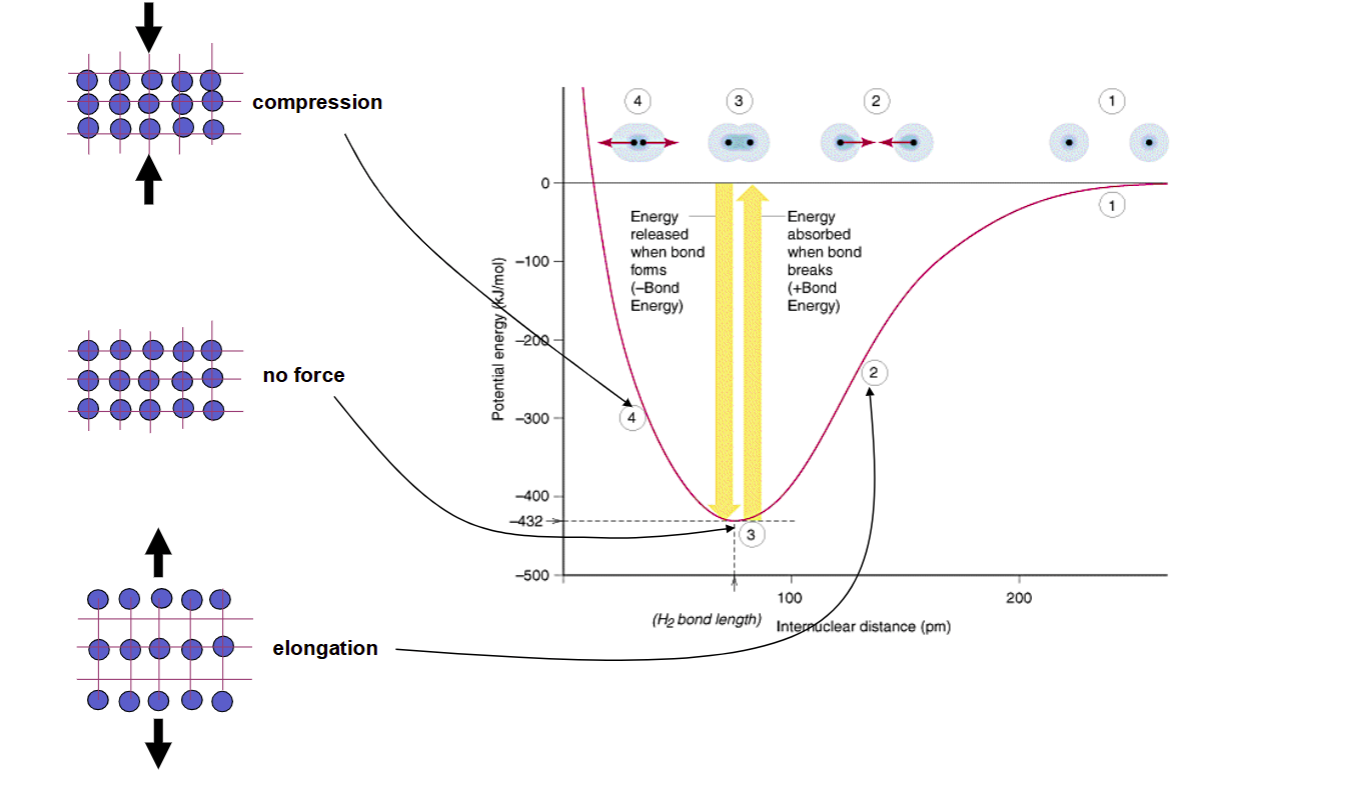

Elastic Deformation Diagram

Elastic vs Plastic

Elastic

stretching of chemical bonds

Plastic

rearrangement of atoms or lattice structure

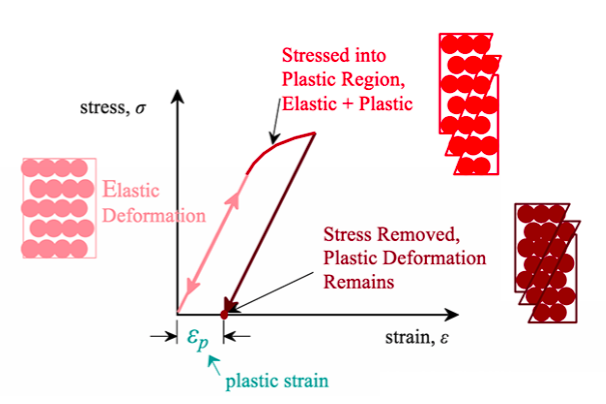

Plastic Deformation Occurs by

dislocation motion

diffusion of vacancies

sliding along grain boundaries

Plastic Deformation Graph

Fracture Graph

Fatigue

progressive and localized structural damage that occurs when a material is subjected to repeated cyclic loading or stress

Safety Factor

X = failure life/desired service life

Safety Factor for Fatigue

X fatigue = # cycles to failure/# cycles in service

Creep Deformation

gradual and time-dependent deformation of a material that occurs under constant load or stress at elevated temperatures

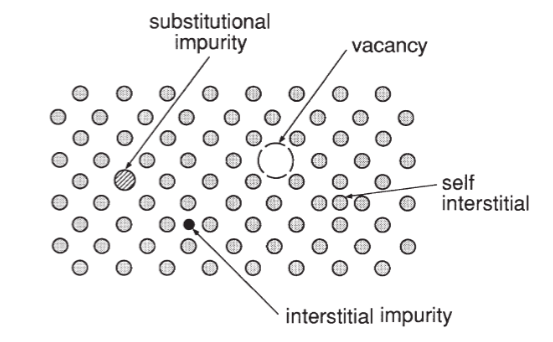

Example of how defects in crystal can alter its properties

increases conductivity of semiconductors

changes colors of insulators and glass

uptake of small atoms such as hydrogen

Types of defects in crystal

point defects, line defects, and planar defects

Point Defects

vacancy

self interstitial

interstitial impurity atom

substitutional impurity atom

Volume Defects

large macroscopic vacancies or precipitates in material

Volume defects good and bad

Good:

reduce weight

serve as filter

voids where cells may interact with material

greater bonding strength of surface

Bad:

reduced mechanical properties

stress concentrations

permeable to water

Porosity = Vp = 1 - Vs (volume fraction of solid phase)

Mechanisms of plastic deformation in metals

slip and twinning

which plane is most likely to promote slippage?

one with highest planar densities

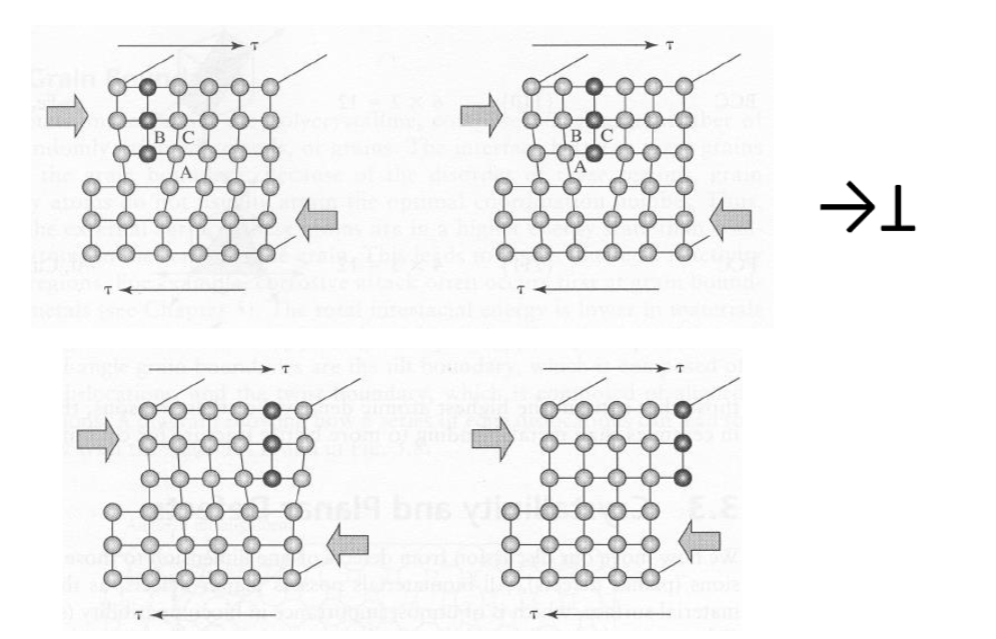

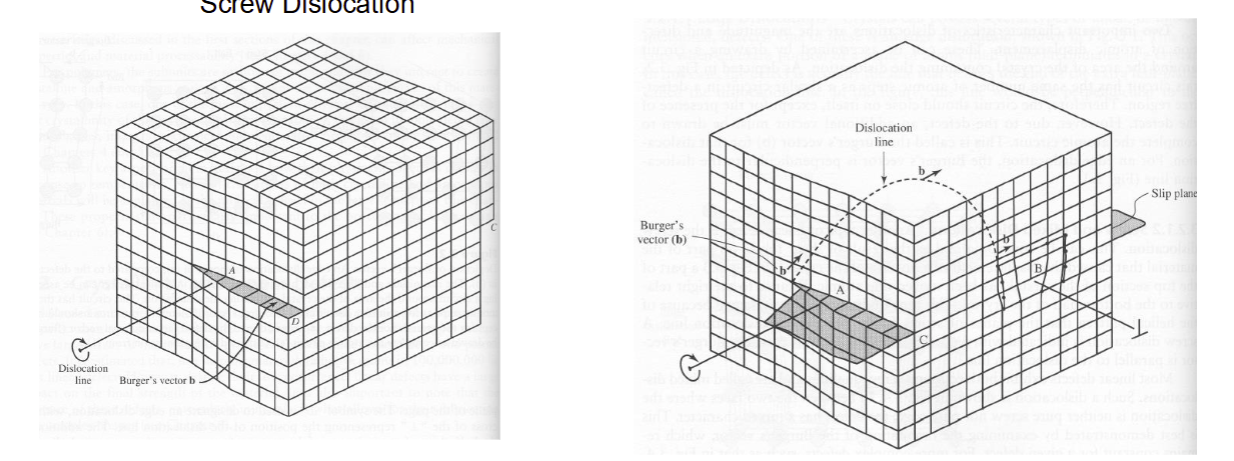

Dislocations (Linear Defects)

linear defects in the material crystal structure

extra half-plane of atoms present

localized lattice strains

Dislocation Motion

move throughout crystal structure

one atom wide, glides through the crystal

glide along the atomic planes int he direction of the Burger’s vector

shear stresses move dislocations

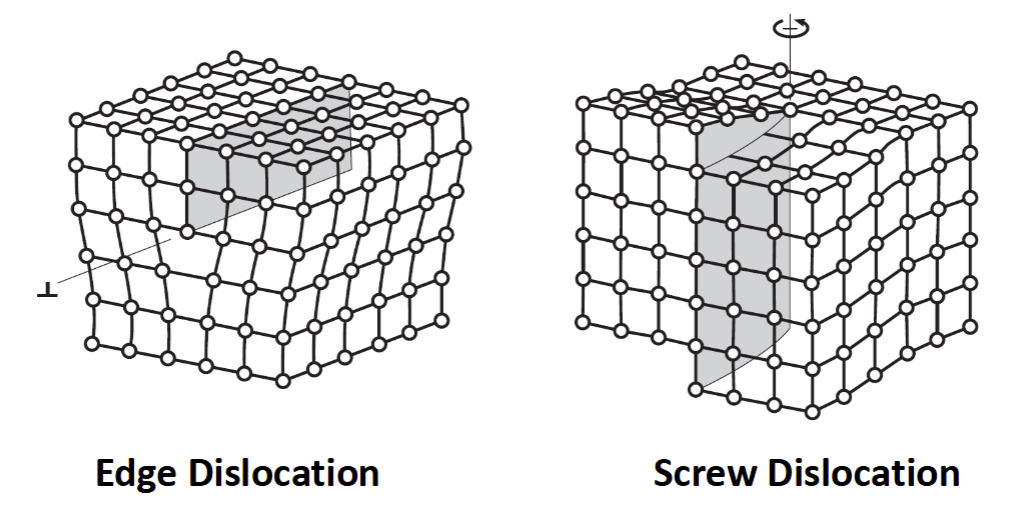

Two Basic Types of Dislocations

edge dislocation and screw dislocation

Screw and Mixed Dislocations

where does slip and climb occur?

at dislocations

where does slide of atoms occur?

grain boundaries

What happens when a dislocation reaches another dislocation?

Annihilation: Dislocations with opposite signs ($\vec{b}$ and $-\vec{b}$) on the same plane attract and cancel out, restoring the lattice.

Repulsion & Pile-up: Dislocations with the same sign on the same plane repel each other. This causes "traffic jams" (pile-ups) that increase the stress needed for further deformation.

Intersection (Jogs/Kinks): When they cross different planes, they "nick" each other:

Jogs: Steps that move the line out of the slip plane (high resistance).

Kinks: Steps within the slip plane (low resistance).

Reaction: They may combine to form a new dislocation if it reduces total energy (if $b_{new}^2 < b_1^2 + b_2^2$).

What happens when a dislocation reaches the end of the crystal (grain)?

1. At a Free Surface: Surface Steps

When a dislocation reaches the external edge of a crystal, it exits the lattice entirely.

The Result: It creates a microscopic "ledge" or surface step exactly one Burgers vector ($\vec{b}$) in height.

The Physics: The dislocation is annihilated because it no longer exists within the bulk. While this reduces the internal strain energy of the crystal, it slightly increases the surface energy by creating new surface area.

2. At a Grain Boundary: Obstruction & Pile-up

Grain boundaries act as powerful walls because the atomic planes in the neighboring grain are tilted at a different angle.

The Obstruction: The dislocation cannot easily "jump" into the next grain because its slip plane and Burgers vector don't align with the new crystal's orientation.

The Pile-up: Subsequent dislocations moving on the same plane get stuck behind the first one, like a traffic jam at a toll booth. This is called a dislocation pile-up.

Stress Concentration: The pile-up creates a massive local stress field. Eventually, this stress may become high enough to "activate" a new dislocation source in the neighboring grain.

3. The Big Picture: Grain Refinement

This interaction is the basis of the Hall-Petch Effect.

Smaller Grains = More Boundaries: More boundaries mean more obstacles for dislocations.

Strength: Because the dislocations are pinned and cannot move easily, the material becomes much stronger and harder.

How would grain size affect dislocation motion?

Grain size is essentially the "length of the runway" for a dislocation. The smaller the grain, the shorter the runway, and the harder it is for the material to deform.

Here is how grain size dictates the behavior of dislocations:

1. The Grain Boundary as a Barrier

A grain boundary is the interface where two crystals with different orientations meet. Dislocations move along specific planes and directions (slip systems). When a dislocation hits a grain boundary, it stops because:

Disorientation: The slip plane in Grain A doesn't line up with the slip plane in Grain B.

Disorder: The boundary is a region of atomic mismatch, making it energetically "expensive" for the dislocation to pass through.

2. The Mean Free Path

The "mean free path" is the distance a dislocation can travel before hitting an obstacle.

Large Grains: Dislocations can travel long distances, build up speed (metaphorically), and require less external stress to move through the bulk of the grain.

Small Grains: The density of barriers is much higher. A dislocation can only travel a tiny distance before it’s pinned against a wall. This significantly restricts overall plastic flow.

3. The Power of the Pile-Up (The Hall-Petch Effect)

This is the most critical part. When dislocations get stuck at a grain boundary, they form a pile-up. This pile-up acts like a magnifying glass for stress:

In a large grain, you can fit many dislocations into one pile-up. The combined stress field of all those dislocations "pushes" on the grain boundary, making it easier to trigger a new dislocation in the next grain.

In a small grain, there isn't enough room for a big pile-up. With fewer dislocations pushing, you need much more external force to get the deformation to move into the neighboring grain.

Grain Boundary

the interface of neighboring grains

atoms on edge of grain have a …

higher energy state and higher chemical reactivity (ex: corrosion)

Small grains properties

large boundary area

edge dislocation will meet a high angle grain boundary and will not form

colling metal quickly can create small grains

large grains properties

longer range crystal structure

edge dislocations easily propagate through low angle grain boundaries

how type and degree of defects effect material properties

point defects induce lattice strains and alter crystal strength

dislocations induce lattice strains and can move affecting ductility

grain size can alter material strength

porosity can affect bulk material strength